arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y...

Transcript of arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y...

![Page 1: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

Eur. Phys. J. C manuscript No.(will be inserted by the editor)

Holographik, the k-essential approach to interactive modelswith modified holographic Ricci dark energy

Mónica Fortea,1

1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428Buenos Aires, Argentina

Received: date / Accepted: date

Abstract We make a scalar representation of interactive models with cold dark matter andmodified holographic Ricci dark energy through unified models driven by scalar fields withnon-canonical kinetic term. These models are applications of the formalism of exotic k-essences generated by the global description of cosmological models with two interactivefluids in the dark sector and in these cases they correspond to usual k-essences. The formal-ism is applied to the cases of constant potential in Friedmann-Robertson-Walker geometries.

1 Introduction

There are a number of cosmological observations, particularly from Type Ia Supernovae [1–3], Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation [4], and Baryon Accoustic Oscillation [5, 6]showing an accelerating effect on the expansion of our universe. Therefore, there must be acosmological component responsible for the repulsive behavior that allows counteract andovercome the gravitational atraction. For this constituent with negative pressure, dubbeddark energy (DE), there have been some proposals. The cosmological constant seems togive the best fit with the observations but also there are good dynamical models includingquintessence [7–11], k-essence [12–23], models with internal structure as quintom [24–27]and N-quintom [28] and applications of holographic principle [29] to cosmology [30–34].The other majority contribution to the source of Einstein equations is called dark matter(DM), and is the ingredient that comes to supplement the lack of observed non-relativisticmatter. Again, we cannot say anything about its nature and moreover, we cannot argue withsome symmetry or microphysical criteria that it is evolving regardless of the DE. In fact,the possibility of an interaction between DM and DE has received many attention in theliterature [35–46] and appears to be even favored over non-interacting cosmologies [47].This work has the goal of showing the connection between models led by common k-essences (but with special conditions on the signs of the first and second derivatives) andinteractive models of CDM and MHRDE fluids. The idea has precedents in the linking ofexotic quintessences [48] or exotic k-essences [49] with interactive systems of two arbi-trary perfect fluids, but here that purely k-essence φ is derivable from a Lagrangian of theform L = −V0F(φ 2) and the interactive systems are compound with fluids whose con-tinuity equation can be replaced by a modified equation using constant coefficients. The

ae-mail:[email protected]

arX

iv:1

605.

0614

0v1

[gr

-qc]

19

May

201

6

![Page 2: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

2

holographic DE fluid used here was proposed in [50] as the unique component of a cosmo-logical model that avoided the problem of causality [51] and in the context of interactivesystems it was used in a plethora of models [52–58].

The paper is organized as follows: In Section 2 we consider the non-canonical scalar rep-resentation of an interacting cosmological model realized with CDM and a MHRDE fluidand introduce the expressions of the different physical magnitudes in terms of the constantpotential V0 and of the suitable kinetic functions F of a k-essence field φ . In Section 3 wegain deeper insight into the subject analyzing the equation that must be fulfilled by the ki-netic functions and the related interactions Q(V0,F). Also there, we show worked examplesin both ways. On the one hand, for a given interaction we obtain the corresponding kineticfunction and on the other hand we discover which interaction can be considered associatedwith widely studied k-essences. In Section 4 we draw conclusions about the examples interms of the workability provided by the scalar representation and also on the generation ofnew functional forms of interaction that can be studied analytically.

2 The holographic k-essence

We consider a model consisting of two perfect fluids with an energy-momentum tensorTik = T (1)

ik +T (2)ik where T (n)

ik =(ρn+ pn)uiuk+ pngik , being ρn and pn the energy density andthe equilibrium pressure of fluid n and ui their four-velocity. Assuming that the two fluidsinteract between them in a spatially flat, homogeneous and isotropic Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) cosmological background, the Einstein equations reduce to:

3H2 = ρ1 +ρ2 ≡ ρ, (1)

ρ1 + ρ2 +3H[(1+ω1)ρ1 +(1+ω2)ρ2] = ρ +3H(1+ω)ρ = 0, (2)

where H = a/a and a stand for the Hubble expansion rate and the scale factor respectivelyand where we consider equations of state (EoS) ωi = (pi/ρi) for i = 1,2. Above, we haveassumed an overall perfect fluid description with an effective equation of state, ω = p/ρ =−2H/3H2−1, where p = p1 + p2 and ρ = ρ1 +ρ2. The dot means derivative with respectto the cosmological time and from equations (1), (2) we get

−2H = (1+ω1)ρ1 +(1+ω2)ρ2 = (1+ω)ρ. (3)

In this paper we use as dark energy (DE) a generalized characterization of the holo-graphic fluid described in [50, 59], as the simplest case of general functions of Hubbleparameter and its derivative, for which the models avoid the causality problem. Then, theholographic energy density ρ2 is written as

ρMHR2 =

2A−B

(H +32

AH2), (4)

where A and B are two arbitrary constants that we can suppose that they satisfy A > B > 0.From (3) and (4) we obtain

(1+ω1)ρ1 +(1+ω2)ρ2 = Aρ1 +Bρ2, (5)

which is a very useful relation because in our description of the interactive system, neces-sarily, the equations of state must be constant and in general, this does not happen with the

![Page 3: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

3

EoS of the holographic fluid. Note also that the expressions (1), (2) and (5) allow us to writethe partial densities of energy as

ρ1 =−Bρ +ρ ′

A−Bρ2 =

Aρ +ρ ′

A−B, (6)

for ρ ′ = ρ/3H.The interaction Q that connects both fluids is specified through the partial equations of

conservation

ρ1 +3H(1+ω1)ρ1 =−3HQ (7a)

ρ2 +3H(1+ω2)ρ2 = 3HQ. (7b)

Or better, a modified interaction QM can be defined by using the relations (5) and (7) bymeans of

ρ1 +3HAρ1 =−3HQM (8a)

ρ2 +3HBρ2 = 3HQM. (8b)

Clearly, the relation between QM and Q is QM = Q+(1−A)ρ1 = Q+(B−ω2−1)ρ2,where we apply the formalism to interactions between cold dark matter (CDM) and modifiedholographic Ricci type dark energy (MHRDE) fluid.

Now, as it was done with the exotic canonical scalar field in [48] and with the exotikfield in [49], we propose that the interactive system as a whole be represented by a unifiedmodel driven by a special class of purely k-essence field φ (labeled by a constant potentialV0 and a kinetic function F(x), x =−φ 2), through the relationship

(1+ω)ρ = Aρ1 +Bρ2 =−2V0xFx(x), Fx =dF(x)

dx. (9)

Then, the global density of energy ρ and the global pressure p = ωρ can be written as

ρ =V0(F(x)−2xFx(x)), p =−V0F(x). (10)

The field φ satisfies the equation of movement

[Fx +2xFxx] φ +3HFxφ = 0 Fxx = dFx/dx, (11)

that allows us to find the functional form of the k-field φ once the kinetic function F(x)is given. If the kinetic function is strictly monotonic Fx 6= 0, there is the well-known firstintegral √

−xFx = m0a−3, (12)

for m0 a constant of integration. Alternatively, when the kinetic functions have an extremexe = x(te) such that Fx(xe) = 0, the above first integral (12) does not exist. Instead, at timet = te, the equation (11) is reduced to xeFxx(xe)φ |te = 0 and thus it must happen that φ has aroot or an extreme at t = te, or that F(x) has a saddle point at xe. We will not address caseswith non-monotonic kinetic functions.

We must note that, from (4), (6), (10) and (11) the partial densities of energy are

ρ1 =−V0

A−B(BF(x)−2xFx(x)(B−1)) (13a)

![Page 4: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/4.jpg)

4

ρMHR2 =

V0

A−B(AF(x)−2xFx(x)(A−1)) =

A−1−ω

A−Bρ (13b)

and therefore, being A−B > 0 the maximum possible value for the overall EoS should beω = ωmax = A− 1. This one is the first characteristic that these "special" k essences mustfulfill and interestingly, it comes exclusively from the associated interactive models usingMHRDE fluids because ρMHR

2 must be non-negative. The expression for the global equationof state ω in the unified representation of the k-essence, is

ω =− FF−2xFx

, (14)

and so (13b) and (14) imply −2xFx/(F−2xFx)≤ A.Also, from (3) and (5) is ω = (A− 1+(B− 1)r)/(1+ r), where r = ρ2/ρ1. Thus, if

the universe supports a constant EoS ω = ω0, then the ratio between densities must be aconstant r = r0 = (A− 1−ω0)/(1+ω0−B). Conversely, in these models with interactiveMHRDE fluid, we cannot have a stationary solution to the problem of coincidence, r = r0,without paying the price of a universe with constant EoS ω0. In that sense, from (14) wecan see that the polynomial kinetic functions F = (−x)n with n = constant, have constantω = (2n−1)−1. Therefore the interactive models with interactions associated with these F ,should not be considered interesting examples to describe realistic cosmological models.

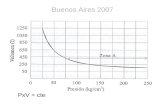

The figure 1 describes the global EoS ω = g/(1−g) in terms of the auxiliary functiong ≡ F/(2xFx) and also shows the prohibited zone ω ≥ A− 1. There, the left branch (g <1− 1/A) correctly describes a unified model which behavior interpolates between a stiff[60, 61], radiation or dust type (for A = 2,4/3 or 1) and a cosmological constant type. Theright branch (g > 1) describes phantom models provided that the EoS is kept ω <−1 alongthe whole cosmological history.

Let us focus on left branch. The bound ω ≤ A−1 results in the bound g≤ 1−1/A andtherefore in the "bounding" functions F(x)max = F0(−x)A/(2(A−1)) for A = 2 or A = 4/3 andanyone for which g < 0 if A = 1. The meaning of "bounding" is evident in figure 2, wherethe general behaviors of ω(x) for different functions F appear "limited" by the curve withn = 0

Other two conditions exist to carry out for these functions, which come from the realityof the Hubble factor H and from the stability of the model. From (10) the total densityof energy can be written as ρ/V0 = 2xFx(g− 1). and with positive potentials and g < 1 itmust always be observed that Fx > 0. Therefore, this second condition leads to F < 0 for0 < g < 1−1/A and to F > 0 for g < 0.

The last restriction arises on having considered the adiabatic speed of sound c2s =

(δ p/δρ)s = px/ρx, (the subscript s means at constant entropy), because the local stabilityand causality requirements 0 ≤ c2

s ≤ 1 [62–68] determine, through c2s = Fx/(Fx + 2xFxx)

that the realistic models are those with Fxx ≤ 0. All the three conditions: g < 1, Fx > 0 andFxx ≤ 0, are essential to describe realistic models driven by k-essence that are associatedwith acceptable interactions Q in the dark sector.

There are several functions that satisfy these three conditions. For example the quadraticfunction F [x] =−mx2 +nx+c, which includes the linear one, the proportional to the tachy-onic function F [x] = m

√1+ x+ n, the exponential F(x) = e−mx2

+ n and also F(x) =−mcosh(

√−x) with m > 0, n > 0 and c > 0. Some of them will be used in the next

section to find the appropriate associated interaction Q in the dark sector. The figure 2shows the EoS corresponding to functions F(x)sti f f = −mx+ n, F(x)rad = −mx2 + n and

![Page 5: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/5.jpg)

5

F(x)dust = e−mx2+n, with m > 0 and n > 0, for which we can see the corresponding asymp-

totic limits.

-1

0 1

A-1

1-1A

F

2 xFx

Ω

Fig. 1 Evolution of the global equation of state for the holographik unified model as a function of the mag-nitude g = F/(2xFx). The shaded area corresponds to the prohibited values ω ≥ A− 1, throughout all theevolution of the model. The maximum ωM = A−1 is reached at g = (A−1)/A belonging to the left branchof the graph, the more useful in modeling realistic universes. The right branch is related with phantom uni-verses. The models with asymptotic stiff behavior must have g ≤ 1/2 and those with asymptotic radiationbehavior must have g≤ 1/4. The models with asymptotic dust behavior must have g≤ 0 and F ≥ 0.

Note that the global equation of state of the k-essence is independent of the potentialused and therefore the above results preserve their validity for variable forms of V , but inthese last cases the first integral (12) no longer exists. Moreover, note that the crossing ofthe phantom divide line (PDL) is not allowed.

3 The associate interactions

The results of the previous section are quite general and apply to any kinetic function F(x),but the particular choice of the function will be determined by the interaction Q that managesthe evolution of both fluids. The expressions (8b) and (14) let us write the equation that mustbe fulfilled by the kinetic function F(x) once the interaction QM(V0,F) is fixed.(

QM

V0−B

[AF−2x(A−1)Fx]

(A−B)

)(2M− (A−B)N

)+2xFxAN = 0, (15)

with M = Fx + xFxx and N = ((2−A)Fx−2xFxx(A−1))/(A−B).The expression QM(V0,F) means that the interaction, often expressed as a function of ρ

and its derivatives, should be given using equations (6), (10), (12) and ρ ′ = 2xF(x)V0.

![Page 6: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/6.jpg)

6

AsymptoticStiff EoS

F=mx+n

Ω=mx + n

mx - n

5x+1x+1

x+5

-8 -6 -4 -2 0

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

x

ΩHxL

AsymptoticRadiation EoS

F = - mx2 + n

Ω =mx2 - n

3 mx2 + n

. - . - - 6x2 + 1

. . . . - x2 + 1

- - - - - x2+ 5

-8 -6 -4 -2 0

-1.0

-0.8

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

x

ΩHxL

Asymptotic Dust EoS F = ã-mx2+ n

Ω = -1 + nãmx2

4 mx2 + 1 + nãmx2

n=0, m=1n=0, m=0.05

n=

0.00

005,

m=

1

n=

0.00

0025

,m

=1

n=

0.00

005,

m=

0.1

n=

0.00

0025

, m=

0.1

n=

0.00

0025

, m=

0.05

-30 -25 -20 -15 -10 -5 0-1.2

-1.0

-0.8

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

ΩHxL

Fig. 2 Top panel: EoS interpolating between ω = 1 and ω = −1 corresponding to the kinetic functionsF [x] = −mx+ n, m = 1,2,3,4,5,6, n = 1,2,3,4,5.Intermediate Panel: EoS interpolating between ω = 1/3and ω = −1 corresponding to the kinetic functions F [x] = −mx2 + n, m = 1,2,3,4,5,6, n = 1,2,3,4,5.Bottom Panel: EoS interpolating between ω = 0 and ω = −1 or without dust like era, corresponding to thekinetic functions F(x) = e−mx2

+n, with m = 1,0.1,0.05, n = 0,0.00005,0.05.

![Page 7: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/7.jpg)

7

The equation (15) is a highly nonlinear equation for F . However, the change of variablesζ =

∫ρx/(2xFxV0)dx and ρ(x) =V0(F−2xFx) lets us to obtain the more simple differential

equation for ρ ,

ρ′′+(A+B)ρ ′+ABρ = QM(A−B) (16)

with ρ ′ = dρ/dζ and ρ ′′ = d2ρ/dζ 2. This is the holographik version [52] of the alreadyknown source equation for the energy density described in [69]. On the other hand, equation(15) allows using the representation in both directions. One direction is to find the systemhandled by the k essence F that represents the interactive system and the other one is to as-sign an interaction Q to an interactive system that is studied as a unified model of k essence.Let’s have a look at some worked examples.

– Examples Q→ F

– CDM and MHRDEThis interesting case was already presented at the general formalism developed in[49], where it was applied to the null interaction Q = 0 or equivalently when wereplace QM = (1−A)ρ1 in (15). The solution is F(x) = (F0 +F1

√−x)B/(B−1) with

F0 < 0, F1 > 0, 0 < B < 1 and lets writing the densities of energy ρMHR = b1a−3 +b2a−3B and ρMHR

2 = ((A−1)/(A−B))b1a−3+b2a−3B. It can be seen that the MHRfluid is always a self-interacting component, because even when Q is null, the darkenergy component is far from remaining independent of the CDM. The asymptoticvalues of the EoS ω =−b2(1−B)a3(1−B)/(b1 +b2a3(1−B)) are 0 and B−1 < A−1in the asymptotic limits a→ 0 and a→ ∞ respectively. However, the model is notviable because always c2

s < 0.

– The holographik Λ

In this example we consider the case in which a holographic interactive fluid isbehind the concept of cosmological constant. The system of a CDM fluid inter-acting with a MHR fluid (5) through the interaction ∆Q = Bρ + (1− ∆)ρ ′, canbe interpreted as a cosmological model driven by a purely k-essence identifiedby the constant potential V0 and the kinetic function obtained from (15), F =

F1 +2F0(1−A)

A (−x)A

2(A−1) , with the positive constants of integration F0 and F1. From(10), (12) and (13b) the expressions for the global density of energy and the densityof energy of MHRDE fluid are

ρ = ΛA−B

A+

ρm

a3A ρ2 = Λ , (17)

respectively, with Λ = AV0F1/(A−B) and ρm = 2V0mA0/(AFA−1

0 ).If 1 < A < 2, the corresponding global EoS

ω =−Λ(A−B)+A(1−A)ρma−3A

Λ(A−B)+Aρma−3A , (18)

ranges between the values ωet = A−1 at early times and ωlt =−1 at late times andthe sound speed is c2

s = A−1 < 1.

![Page 8: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/8.jpg)

8

Solving ρMHR2 = (2H +3AH2)/(A−B) = Λ we obtain the factor of scale

a(t) =(

cosh(κ(t− t0))+H0 sinh(κ(t− t0))) 2

3Aκ

2 = 3AΛ(A−B)/4, (19)

where we set t0 as the present time for which the factor of scale is a(t0) = 1 andHubble parameter is H(t0) = H0. Notice that the argument of the hyperbolic func-tions in (19) corresponds to the usual solution of the factor of scale for the modelΛCDM if B=(A2−1)/A. Also, the expression (17) corresponds to the model Λ plusWDM (A very slightly greater than one) or to the model Λ plus radiation (A = 4/3).However, unlike a true cosmological constant, the equation of state for dark energyω2 = ωρ/ρ2 diverges at early times and tends asymptotically to −∆/A at late timesbecause its expression is

ω2 =−(A−B)

A+

(A−1)ρm

Λa3A . (20)

– The sign-change holographik

There exists a number of works that studied interactions able to change their signalong the evolution of the universe. One of them is Qsc = Bρ2−ρ1 that replaced in(15) allows us to obtain two linear differential equations xFx−y±F = 0 where y± =√

AB/(2(√

AB± 1)) and then, the two kinetic functions F± = F±0 (−x)y± . Usingthe first integral (12) for each particular kinetic function, the corresponding globalenergy density is

ρ = (ρ0−ρ−)a3√

AB +ρ−a−3√

AB, ρ− =V0F−0

(1−√

AB), (21)

with ρ0 the actual global density, and the constant of integration m−0 coming from(12) are taken so that m−0 = −F−0 y−. Therefore, the global EoS oscillates between−(1−

√AB) at early times and −(1+

√AB) at late times as can be seen in

ω =− (ρ0−ρ−)(1+√

AB)a6√

AB +ρ−(1−√

AB)

(ρ0−ρ−)a6√

AB +ρ−. (22)

Assuming ∆ > 0 and√

AB < 1, the change of sign of the interaction is produced atωsc = (AB−1)/(B+1) for which the factor of scale is

asc =

(ρ−(√

AB(B+1)− (A+1)B)(ρ0−ρ−)(

√AB(B+1)+(A+1)B)

) 16√

AB

. (23)

This interactive system affected by Qsc is consistently maintained until ρ1 is ex-hausted at

amax =(

ρ−(√

AB−B)(ρ0−ρ−)(

√AB+B)

) 16√

AB , (24)

when the sign change has already occurred because amax > asc.

![Page 9: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/9.jpg)

9

ΡΡ1 Ρ2

Q

r

Q = BΡ2 - Ρ1

To

da

y0.6 1

0

0.4

0.8

1

0.6 1

0

0.4

0.8

1

a

Fig. 3 Densities of energy, ratio r = ρ1/ρ2 and Qsc for ρ0−ρ− = 0.04, ρ− = 0.96, A = 5/4, B = 3/4.

The figure 3 shows the global density of energy (21) and the partial densities ofenergy

ρ1 =1∆

− (ρ0−ρ−)(

√AB+B)a3

√AB +ρ−(

√AB−B)a−3

√AB, (25a)

ρ2 =1∆

(ρ0−ρ−)(A+

√AB)a3

√AB +ρ−(A−

√AB)a−3

√AB, (25b)

where it can be seen that with the right choice of the constants of integration (ρ0−ρ−) and (ρ−), the model is consistent with current estimates of dark energy densitiesand shows a relief in the problem of coincidence. Also there, the ratio r = ρ1/ρ2 andQsc are depicted for ρ0−ρ− = 0.04, ρ− = 0.96, A = 5/4, B = 3/4.

– Examples F → Q

– The linear function F(x) = 1+mx, with m > 0 was already used in [15, 21] withexponential potentials. Here, with the constant V =V0, is replaced in (15) obtainingthe interaction QM∆ = ABρ +(A+B− 2)ρ ′. That is, a cosmological model withCDM fluid interacting with MHRDE through the interaction ∆Q = Bρ +(B−1)ρ ′

can be seen as a model driven by a purely linear k-essence. With the greatest sim-plicity, the densities of energy and the EoS of the global model are obtained as wellas the time variation of the scale of factor and the k-essence field φ .

ρ =V0 +ρ0

a6 , ρ2 =1∆

(AV0 +(A−1)

ρ0

a6

), (26a)

![Page 10: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/10.jpg)

10

a(t) =[ sinh(

√3V0t)

sinh(√

3V0tT )

]1/3ρ

0 =m2

0V0

m, ω =−V0a6−ρ0

V0a6 +ρ0 , (26b)

φ = φ0 ln(tanh(√

3V0t2

)) φ0 =m0 sinh(

√3V0tT )

m√

3V0, (26c)

with tT the actual time. The adiabatic velocity of sound is constantly equal to 1 as inthe cases of the quintessence regardless of the values of the parameters A and B.

– In [20], the simple quadratic function F(x) = b6 + x− x2

2b is used with the arbitraryparameter b > 0 to ensure positivity of density of energy and stability observedthrough the speed of sound. In this context of purely holographic k-essence withconstant potential V0 it leads, through (15), to the associated interaction QM∆ =ABρ +(A+B−1)ρ ′+ρ ′′/4+ρ ′/(2

√6ρ/bV0) or

Q∆ = Bρ +Bρ′+

ρ ′′

4+

ρ ′

2√

6ρ

bV0

. (27)

From (12) we obtain the algebraic equation h3 + h− u = 0 for h =√−x/b and

u = m0b−1/2a−3, whose unique real solution allows us to write the first integralφ =√−x for the kinetic function as

√−xb

=− (2/3)1/3b1/6a(9+√

3√

4ba6 +27)1/3 +

(9+√

3√

4ba6 +27)1/3

21/332/3b1/6a, (28)

and thus, from (10) and (12) the global energy density ρ = 3V0b2 (1/3−x/b)2 proves

to be

ρ =3V0b

2

[13+

(− (2/3)1/3b1/6a(

9+√

3√

4ba6 +27)1/3 +

(9+√

3√

4ba6 +27)1/3

21/332/3b1/6a

)2]2

,

(29)where the constant of integration in (12) is taken as m0 = 1. The global EoS (14),

ω =−13

(− xb +1+ 2√

3)( x

b −1+ 2√3)

(− xb +1/3)2 , (30)

shows that this interactive model exhibits a dust type behavior ω = 0 when the

time evolution of the k-essence is φ =√−xroot =

√b(−1+2/

√3), that is when

adust = 1.3b−1/6. The figure 4 shows that the dust behavior of the global EoS canbe accommodated by varying the parameter b and also that the EoS has a singlemaximum regardless of b, corresponding to A = 3/2.Thus, the constant A is fixed for the kinetic function and b is fixed by the astro-nomical data. The remaining constants V0 and B are determined by the currentoverall energy of density ρ(a = 1) and by the ratio between dark densities of en-ergy r = ρ1/ρ2 = −(B(F − 2xFx)+ 2xFx)/(AF − 2xFx(A− 1)) at its present valuer(a = 1) respectively.

![Page 11: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/11.jpg)

11

F=b

6+x-

x2

2 bb=2

b=1

b=14

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

a

ΩHaL

Fig. 4 Global equation of state for the quadratic function F(x) = b6 + x− x2

2b for different parameters b. Itcan be seen that the maximum is independent of b

The adiabatic velocity of sound c2s = Fx/(Fx +2xFxx) = (b− x)/(b−3x) oscillates

between c2s |et = 0 at early time and c2

s |lt = 1/3 at late times.

– The kinetic function F = α−β cosh(√−x) with α > β > 0 meets the requirement

Fx = β sinh(√−x)/(2

√−x) > 0 in order that the density of energy is always posi-

tive and Fxx =−(β cosh(

√−x)/(4(−x)3/2

)(√−x− tanh(

√−x)

)< 0 for the global

model is stable. Then, using (12) we find that√−x = sinh−1(a−3) if the constant of

integration is taken as m0 = β/2 and thus the global density of energy is

ρ =V0

(α− β

a3

√1+a6 +

β

a3 sinh−1(a−3)). (31)

This expression (32) can be considered as the global density of energy of an in-teractive cosmological system filled with CDM and MHRDE that affected by theinteraction Q

∆Q = B(ρ +ρ′)+βV0

[αV0− (ρ +ρ ′)

βV0− βV0

αV0− (ρ +ρ ′)

], (32)

produces a density of energy for the holographic component

ρMHR2 =

V0

∆

[Aα−A

β√

1+a6

a3 +β (A−1)

a3 sinh−1(a−3)]. (33)

The corresponding global EoS

ω =αa3−β

√1+a6

−β sinh−1(a−3)−αa3 +β√

1+a6, (34)

![Page 12: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/12.jpg)

12

has asymptotic values ωe = 0 for a = 0 and ωl = −1 at late times. Neverthelessthe maximum value of ω is positive in the intermediate epoch between the asymp-totic dust era a = 0 and the truly dust era a = β 1/3(α − β )−1/6(α + β )−1/6 be-cause g=(α−β cosh(

√−x))/(−2β

√−xsinh(

√−x) is not always negative at early

times. Note that the constants α and β should be adjusted so that the holographicdensity is kept positive and the quotient of densities in the dark sector fits with thecurrent value. The adiabatic velocity of sound c2

s = (sinh−1(a−3)√

1+a6)−1 oscil-lates between c2

s = 0 at early times and c2s = 1 at late times, independently from the

constants A, B, α and β .

4 Conclusions

In this work we have studied cosmological models driven by k-essences with constant po-tential V0, generated by strictly increasing (Fx > 0) and concave (Fxx < 0) kinetic functionsF . The study is described in a FRW background and the goal was the possibility of findinglinks between these universes and interactive models filled with CDM and MHRDE fluids.This idea is supported on studies realized previously where scalar representations of cosmo-logical interactive arbitrary systems were found using exotic quintessence [48] and exotick-essence as scalar fields [49]. Here we particularize the interactive model, considering it asintegrated by CDM and MHRDE fluid, whose defining parameters A and B mark limits onthe used k-essences. According to the general method described in [49], the fields turn outto be common k-essences derived from a Lagrangian L = −V0F . This fact could allow usto consider this formalism as an indirect or covert Lagrangian description of a cosmologicalsystem with interactive dark energy [70]. In the k-essential approach of the cosmologicalmodels they do not have allowed the crossing of phantom divide (ω = −1). This is clearlyseen in the figure 1 where the global EoS ω = g/(1− g) is plotted as function of an aux-iliary magnitude g = F/2xFx. There are two branches in the picture, one describing viableuniverses and the other corresponding to phantom universes, and the cosmological constanttype behavior is the asymptotic conduct in the extreme points (Fx = 0), when we arrive at thelow limit g→−∞ of the acceptable branch g < 1 or at the top limit g→+∞ of the phantombranch g > 1. Restricting ourselves to models no phantom for which g < 1, a positive globaldensity of energy leads to the condition Fx > 0 while the stability measured by the adiabaticspeed of sound determines Fxx < 0. These conditions select possible k-essences for the rep-resentation (F → Q) and simultaneously they reject interactions that can lead, through thisapproach, to cosmologically nonviable systems (Q→ F). Two other restrictions on thesemodels of universe arising from the use of CDM and MHRDE as interacting fluids are theinability to have constant ratios r = r0 to alleviate the problem of the coincidence withouthaving a global constant EoS ω = ω0 (because r = r0 = (A− 1−ω0)/(1+ω0−B)), andthe existence of a maximum value for the global EoS ωmax = A−1.

The link between both schemes arises of equalizing the expressions of the time deriva-tive of Hubble parameter−2H = (ρ + p) =−2xFxV0 in each description and of supposing alinear combination of density of energy and of pressure for the DE. Then, the conservationequation for the DE gives us the expression that must be hold for the kinetic function Fand for the interaction Q. From (15), given the interaction Q(V0,F), the finding of the func-tion F allows to write all the densities of energy as function of the factor of scale throughthe expressions (10), (12) and (13). Inversely, given the appropriate function F we find theinteraction that affects the CDM-MHRDE system. The last two sections were dedicated togiving examples of these two manners of using (15). To the systems CDM-MHRDE affected

![Page 13: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/13.jpg)

13

by the interactions Q = 0, QΛ = (Bρ +(1−∆)ρ ′)/∆ , and Qsc = Bρ2−ρ1 we associate sys-

tems driven by the k-essences F(x) = (F0 +F1√−x)B/(B−1), F = F1 + 2F0

(1−A)A (−x)

A2(A−1)

and F± = F±0 (−x)y± respectively, showing that they arrive at the same dynamic results inboth approaches, but in a more direct way. Also, in the particular case QΛ we show that theconcept of cosmological constant can be interpreted as the result of an interaction in thesesystems CDM-MHRDE. For the inverse way, we use the kinetic functions F(x) = 1+mx,F(x) = b

6 + x− x2

2b and F = α−β cosh(√−x) to obtain interactions not usually considered

in the literature, Q = (Bρ + (B− 1)ρ ′)/∆ , Q = (Bρ +Bρ ′+ ρ ′′

4 + ρ ′(6ρ/bV0)−1/2

2 )/∆ , and

Q = [B(ρ +ρ ′)+βV0[αV0−(ρ+ρ ′)

βV0− βV0

αV0−(ρ+ρ ′) ]]/∆ respectively. The latter case shows thedifference between the maximum value of the global EoS and its asymptotic limits. More-over in the last two cases, we obtained interactions that difficultly could be solved by themethod of the equation source and for which, nevertheless, we obtained explicit expressionsfor all the cosmological important magnitudes.

References

1. A. G. Riess et al. [Supernova Search Team Collaboration], Astron. J. 116, 1009 (1998)doi:10.1086/300499 [astro-ph/9805201].

2. S. Perlmutter et al. [Supernova Cosmology Project Collaboration], Astrophys. J. 517,565 (1999) doi:10.1086/307221 [astro-ph/9812133].

3. R. Amanullah et al., Astrophys. J. 716, 712 (2010) doi:10.1088/0004-637X/716/1/712[arXiv:1004.1711 [astro-ph.CO]].

4. D. N. Spergel et al. [WMAP Collaboration], Astrophys. J. Suppl. 170, 377 (2007)doi:10.1086/513700 [astro-ph/0603449].

5. D. H. Weinberg, M. J. Mortonson, D. J. Eisenstein, C. Hirata, A. G. Riess and E. Rozo,Phys. Rept. 530, 87 (2013) doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2013.05.001 [arXiv:1201.2434[astro-ph.CO]].

6. W. J. Percival, S. Cole, D. J. Eisenstein, R. C. Nichol, J. A. Peacock, A. C. Popeand A. S. Szalay, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 381, 1053 (2007) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12268.x [arXiv:0705.3323 [astro-ph]].

7. I. Zlatev, L. M. Wang and P. J. Steinhardt, Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 896 (1999)doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.896 [astro-ph/9807002].

8. R. R. Caldwell, R. Dave and P. J. Steinhardt, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 (1998) 1582doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.1582 [astro-ph/9708069].

9. J. A. Frieman, C. T. Hill, A. Stebbins and I. Waga, Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2077 (1995)doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.2077 [astro-ph/9505060].

10. P. J. E. Peebles and B. Ratra, Astrophys. J. 325, L17 (1988). doi:10.1086/18510011. B. Ratra and P. J. E. Peebles, Phys. Rev. D 37, 3406 (1988).

doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.37.340612. C. Armendariz-Picon, V. F. Mukhanov and P. J. Steinhardt, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4438

(2000) doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4438 [astro-ph/0004134].13. C. Armendariz-Picon, V. F. Mukhanov and P. J. Steinhardt, Phys. Rev. D 63, 103510

(2001) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.63.103510 [astro-ph/0006373].14. E. J. Copeland, M. Sami and S. Tsujikawa, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 15, 1753 (2006)

doi:10.1142/S021827180600942X [hep-th/0603057].15. L. P. Chimento, Phys. Rev. D 69, 123517 (2004) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.123517

[astro-ph/0311613].

![Page 14: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/14.jpg)

14

16. T. Chiba, Phys. Rev. D 66, 063514 (2002) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.66.063514 [astro-ph/0206298].

17. S. Tsujikawa and M. Sami, Phys. Lett. B 603, 113 (2004)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.10.023 [hep-th/0409212].

18. M. Malquarti, E. J. Copeland, A. R. Liddle and M. Trodden, Phys. Rev. D 67, 123503(2003) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.67.123503 [astro-ph/0302279].

19. J. M. Aguirregabiria, L. P. Chimento and R. Lazkoz, Phys. Rev. D 70, 023509 (2004)doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.70.023509 [astro-ph/0403157].

20. L. P. Chimento, M. I. Forte and R. Lazkoz, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 20, 2075 (2005)doi:10.1142/S0217732305018074 [astro-ph/0407288].

21. L. P. Chimento and M. I. Forte, Phys. Rev. D 73, 063502 (2006)doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.063502 [astro-ph/0510726].

22. C. Armendariz-Picon and E. A. Lim, JCAP 0508, 007 (2005) doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2005/08/007 [astro-ph/0505207].

23. M. Li and X. Zhang, Phys. Lett. B 573, 20 (2003) doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2003.08.041[hep-ph/0209093].

24. Z. K. Guo, Y. S. Piao, X. M. Zhang and Y. Z. Zhang, Phys. Lett. B 608, 177 (2005)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.01.017 [astro-ph/0410654].

25. Y. F. Cai, E. N. Saridakis, M. R. Setare and J. Q. Xia, Phys. Rept. 493, 1 (2010)doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2010.04.001 [arXiv:0909.2776 [hep-th]].

26. B. Feng, X. L. Wang and X. M. Zhang, Phys. Lett. B 607, 35 (2005)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.12.071 [astro-ph/0404224].

27. B. Feng, M. Li, Y. S. Piao and X. Zhang, Phys. Lett. B 634, 101 (2006)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2006.01.066 [astro-ph/0407432].

28. L. P. Chimento, M. I. Forte, R. Lazkoz and M. G. Richarte, Phys. Rev. D 79, 043502(2009) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.79.043502 [arXiv:0811.3643 [astro-ph]].

29. G. ’t Hooft, Salamfest 1993:0284-296 [gr-qc/9310026].30. W. Fischler and L. Susskind, [hep-th/9806039].31. O. Aharony, S. S. Gubser, J. M. Maldacena, H. Ooguri and Y. Oz, Phys. Rept. 323, 183

(2000) doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(99)00083-6 [hep-th/9905111].32. R. Bousso, Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 825 (2002) doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.825 [hep-

th/0203101].33. R. Bousso, JHEP 9907, 004 (1999) doi:10.1088/1126-6708/1999/07/004 [hep-

th/9905177].34. S. D. H. Hsu, Phys. Lett. B 594, 13 (2004) doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.05.020 [hep-

th/0403052].35. L. Amendola, Phys. Rev. D 62, 043511 (2000) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.62.043511

[astro-ph/9908023].36. G. Mangano, G. Miele and V. Pettorino, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 18, 831 (2003)

doi:10.1142/S0217732303009940 [astro-ph/0212518].37. S. del Campo, R. Herrera and D. Pavon, Phys. Rev. D 70, 043540 (2004)

doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.70.043540 [astro-ph/0407047].38. G. R. Farrar and P. J. E. Peebles, Astrophys. J. 604, 1 (2004) doi:10.1086/381728 [astro-

ph/0307316].39. Z. K. Guo, R. G. Cai and Y. Z. Zhang, JCAP 0505, 002 (2005) doi:10.1088/1475-

7516/2005/05/002 [astro-ph/0412624].40. Z. K. Guo and Y. Z. Zhang, Phys. Rev. D 71, 023501 (2005)

doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.71.023501 [astro-ph/0411524].

![Page 15: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/15.jpg)

15

41. R. G. Cai and A. Wang, JCAP 0503, 002 (2005) doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2005/03/002[hep-th/0411025].

42. B. Gumjudpai, T. Naskar, M. Sami and S. Tsujikawa, JCAP 0506, 007 (2005)doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2005/06/007 [hep-th/0502191].

43. R. Curbelo, T. Gonzalez, G. Leon and I. Quiros, Class. Quant. Grav. 23, 1585 (2006)doi:10.1088/0264-9381/23/5/010 [astro-ph/0502141].

44. W. Zimdahl and D. Pavon, Phys. Lett. B 521, 133 (2001) doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(01)01174-1 [astro-ph/0105479].

45. L. P. Chimento, A. S. Jakubi, D. Pavon and W. Zimdahl, Phys. Rev. D 67, 083513 (2003)doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.67.083513 [astro-ph/0303145].

46. G. Olivares, F. Atrio-Barandela and D. Pavon, Phys. Rev. D 71, 063523 (2005)doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.71.063523 [astro-ph/0503242].

47. M. Szydlowski, “Cosmological model with energy transfer,” Phys. Lett. B 632, 1 (2006)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.10.039 [astro-ph/0502034].

48. L. Chimento and M. I. Forte, Phys. Lett. B 666, 205 (2008)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.064 [arXiv:0706.4142 [astro-ph]].

49. M. Forte, Eur. Phys. J. C 76, no. 1, 42 (2016) doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-3882-6[arXiv:1507.03658 [gr-qc]].

50. L. N. Granda and A. Oliveros, Phys. Lett. B 671, 199 (2009)doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.12.025 [arXiv:0810.3663 [gr-qc]].

51. M. Li, Phys. Lett. B 603, 1 (2004) doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.10.014 [hep-th/0403127].

52. L. P. Chimento, M. I. Forte and M. G. Richarte, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 28, 1250235 (2013)doi:10.1142/S0217732312502355 [arXiv:1106.0781 [astro-ph.CO]].

53. L. P. Chimento, M. Forte and M. G. Richarte, Eur. Phys. J. C 73, no. 1, 2285 (2013)doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-013-2285-1 [arXiv:1301.2737 [gr-qc]].

54. P. Pankunni and T. K. Mathew, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 23, 1450024 (2014)doi:10.1142/S0218271814500242 [arXiv:1309.3136 [astro-ph.CO]].

55. E. K. Li, Y. Zhang and J. L. Geng, Phys. Rev. D 90, no. 8, 083534 (2014)doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.083534 [arXiv:1412.5482 [gr-qc]].

56. A. Pasqua, S. Chattopadhyay and R. Myrzakulov, arXiv:1511.00600 [gr-qc].57. M. Sharif and A. Jawad, Astrophys. Space Sci. 337, 789 (2012). doi:10.1007/s10509-

011-0893-558. S. del Campo, J. C. Fabris, R. Herrera and W. Zimdahl, Phys. Rev. D 83, 123006 (2011)

doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.83.123006 [arXiv:1103.3441 [astro-ph.CO]].59. L. N. Granda and A. Oliveros, Phys. Lett. B 669, 275 (2008)

doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.10.017 [arXiv:0810.3149 [gr-qc]].60. Y. B. Zeldovich, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 160, 1P (1972).61. P. H. Chavanis, Phys. Rev. D 92, no. 10, 103004 (2015)

doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.92.103004 [arXiv:1412.0743 [gr-qc]].62. S. W. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis, doi:10.1017/CBO978051152464663. R. M. Wald, Chicago, Usa: Univ. Pr. ( 1984) 491p

doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226870373.001.000164. R. Bean and O. Dore, Phys. Rev. D 69, 083503 (2004)

doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.083503 [astro-ph/0307100].65. M. S. Longair, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-73478-966. T. Padmanabhan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1993)67. P. Coles and F. Lucchin, Chichester, UK: Wiley (2002) 492 p

![Page 16: arXiv:1605.06140v1 [gr-qc] 19 May 2016 · 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: date](https://reader033.fdocuments.us/reader033/viewer/2022050205/5f58778dbb6f8c7fcc793ecd/html5/thumbnails/16.jpg)

16

68. J. Garriga and V. F. Mukhanov, Phys. Lett. B 458, 219 (1999) doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(99)00602-4 [hep-th/9904176].

69. L. P. Chimento, Phys. Rev. D 81, 043525 (2010) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.81.043525[arXiv:0911.5687 [astro-ph.CO]].

70. N. J. Poplawski, gr-qc/0608031.