artigos praticas alternativas

description

Transcript of artigos praticas alternativas

K i t h " dy " th nes et c stoma: e

contribution o f b o d y w o r k to

somat ic educat ion

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

T.W. Myers

Thomas W. Myers 20 Roundabout Dr, Scarborough ME 04074, USA

Correspondence to: 32 W. Myers.

TeL/Fax: + I 207 883 2756; E-mail: [email protected]

Received June 1998

Accepted July 1998

Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies (1999) 3(2), 107-116 © Harcourt Brace & Co. Ltd 1999

Introduction

In Part 1 of this series, (Myers 1998a), we gave the name 'kinesthetic dystonia' to the ubiquitous loss of kinesthetic sensitivity and somatic connection we find in our tables and plinths throughout industrialized cultures. We explored aspects of the bodyworker's role as a kinesthetic educator, and posited that eventually the discoveries made by one-on-one healing would need to be applied in an educational setting if we wish to effect change in the abusmal universality of somatic alienation.

In Part 2 (Myers 1998b), we sketched a line through the history of physical education (PE), the traditional teachers of the kinesthetic sense, exploring the 'fit' between cultures and their approach to PE, with an eye to the needs of the coming century. We also expanded the scope of PE toward 'somatization' - - the process of becoming embodied in any culture, which allowed us to look beyond traditional schooling to include both early familial and general social effects

on this process of embodiment (Cohen 1993).

In Part 3A (Myers 1999) we began to outline a PE agenda for the 21 st century, using values derived from bodywork and movement therapies. Part 3A included a section on 'Total movement'; Part 3B completes our discussion with sections on 'Acture', 'Organismic response', and 'Kinesthetic sensitivity'.

Acture

Once again we must thank Dr Feldenkrais, this time for this coined word, acture, designating 'posture in action' (Feldenkrais 1972). 'Posture' is such a static concept, while structure is constantly in action, even in standing. There is a fairly stable and recognizable pattern, however, in each person's characteristic mode of action, and this reveals itself in every action, from shoveling to eating to simply standing still. While the 'Total movement' section described the ability to move, voluntarily or physiologically, the 'Acture' section

J O U R N A L OF B O D Y W O R K AND M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S APRIL 1999

Myers

describes values that bodywork therapists hold in terms of the position to which one returns after any movement, and the underlying relationships which persist in the supporting parts of the body when any action is undertaken.

Alignment Achieving an easy, relaxed alignment or the basic body segments in gravity is a fimdamental body-mind integration tool. While we can (and do) argue among Rolf, Alexander, Meziere, Aston, Iyengar, and many other lesser luminaries about the precise details of the ideal posture, the basic value of alignment is so unassailable that the wonder is that the mainstream of our technocratic culture has abandoned any technique for inducing alignment. You have only to go back as far as the Victorians to find 'deportment' classes in which children were made to go round with books perched on their heads, as a tool of inducing correct alignment. Although we have developed more effective and less restrictive tools for bringing alignment about, none of these is in general use in schools today, and the results are slouchingly evident outside every secondary school in the Western world (see box in Part 2 on 'Spiraling Into Alignment' JBMT 2 (3).

'Gravity training' - teaching children to find the center of gravity of each body part, how to 'put themselves together' in gravitational alignment, and how to recapture that alignment when it is lost - could usefully substitute for the 'Pledge of Allegiance' as a morning school activity. If alignment was held as a value during sports training, sports careers might persist thanks to less injury or degeneration. Carrying water on the head, long practiced by native women returning from the village well, generates a sense of alignment, which is a joy to behold.

Teaching alignment would include gaining support from the ground, which in turn requires an experiential understanding of the body's 'core' and 'sleeve'. The body's core defies precise anatomical definition, but could be generally defined by imagining the core of the body's 'apple': the spine, and the muscles near the spine, including the scalenes, diaphragm, and pelvic floor, and as well the muscles down the inside of the leg. The body's sleeve, then, becomes most of those muscles to be seen in the familiar ecorch6 representation of the muscles: the traps, lats, pects and delts, the superficial abdominal muscles and the outside of the legs.

The core is designed to gain support from the ground up through the inside of the legs and trunk, and the sleeve is designed to hang off the sturdy core. With no such training or even idea in our educational system, however, few people achieve this basic tenet of alignment, and the two remain unbalanced, generally with the core 'hanging' in the sleeve. Core alignment and strength can be taught.

Length That the body should be as long as possible is an idea that originated with E Matthias Alexander, and was addressed in his seminal contribution, the Alexander Technique (Alexander 1989). Some nods to length can be found in yoga, and many people, such as Ida Rolf and Moshe Feldenkrais, took up the flag in Alexander's wake. In today's world, the idea of length finds its only expression in the idea of 'stretching', which is all well and good for the muscles, but can easily shorten and compress the joints. It is a sad fact: the idea that the body works better as it lengthens away from the earth, giving space to the joints, has yet to gain much ground.

Inducing a lengthened position of the body through class work was also championed early this century by Else Gindler (Gindler 1988). Her work

influenced many, including Mabel Ellsworth Todd and Lulu Sweigard, who taught a lengthened alignment in expanded dance classes (Todd 1937, Sweigard 1958). Both Todd and Sweigard produced an extensive working library of images and exercises designed to promote a deep sense of alignment and release into length.

Releasing into length during movement includes allowing the spine to lengthen to initiate trunk movement, allowing the scapula to drop down the rib cage as the arm is lifted (instead of hiking toward the ear), and letting the femur drop out of the hip as the leg is advanced (as opposed to shortening the groin to flex the leg forward).

The grace and poise that comes from moving through length could be easily taught in 'kinesthesia class', without belaboring the point or taking an inordinate amount of time. The use of a supervised climbing wall in school situations could also make very plain the value of being able to lengthen out through the body.

Palintonicity This neologism (Maitland 1995) describes a state of even tone across the various muscles and connective tissues of our structural body. A palintonic body has supple tone across the various lines of pull of myofascia, rather than having some areas of hypertonicity coupled to other areas of hypotonicity. A number of palintonic lines have been described and their interactions considered (Myers 1997).

Hatha yoga practice, modified Iyengar practice in particular, encourages palintonicity across the planes of myofascia in the body. Also, a good developmental movement program, which encourages recapitulation of development stages of movement, would create the conditions for palintonic balance in students.

A note here on modem exercise: the shiny, crammed weight machines that grace most health clubs these days

JOURNAL OF BODYWORK AND MOVEMENT THERAPIES APRIL 1999

Kinesthetic dystonia

were originally developed for rehabilitation of specific damaged muscles° Their widespread use by the general populace has probably done more good than harm in health promotion, but since these machines are in fact carefully designed to isolate particular muscles or groups, they can get in the way of an even, balanced tonus across an entire articular chain of muscles. As an example, a leg-lifting machine designed to develop only the quadriceps, used to excess without balancing exercises, can result in an inhibition of the ability to extend the hip joint. This could have deleterious effects on pelvic posture and the tonus of, say, the rectus abdominis and the rest of the articular chain that runs along the front of the body.

Combine alignment, length, and palintonicity, and you assure proportion. While the exact dimensions of an ideal proportion have been argued by sculptors and geometers down through the ages from Plato to Leonardo to modern ergonomics, the general value of the idea to somatic practice is obvious. 'Bodyreading' for proportion is a quick and easy way in which teachers could assess these somatic values in their students - and, indeed, students could learn to assess each other (and even their parents). Lack of proportion would be a flag for observers to intervene in some way to restore proportion before the compensation pattern became too embedded for easy restoration.

The body is a structure that depends on the balance of tensional forces in the soft tissues to maintain its balance. Remove the soft tissues, and the skeleton would clatter to the floor, for it has no structural integrity of its own. Despite the continued representation of the musculoskeletal system in textbooks as some kind of complex crane, it is not. Kenneth Snelson discovered, and Buckminster Fuller developed, a class of structural models which isolated compression beams within a balanced ocean of tensional

members, which were dubbed 'tensegrity' structures (Fuller 1975).

Our human structure is a tensegrity structure, and when the palintonic lines that traverse and encircle the body are balanced, 'length' and 'lift' appear (Myers 1997, Schultz & Feitis 1996).

Recent writing in Scientific American and JBMT show how the tensegrity concept applies from the atomic and molecular level, right through the cellular level of the cytoskeleton and its connections to the fascial matrix which surrounds it, all the way to the macro level of our body structure (ingber 1998, Oschman 1997).

Efficient postural adjustments

All of the foregoing should result in the ability of the body to make efficient postural adjustments to changing situations. A point of view articulated particularly clearly by Judith Aston in her Structural Patterning work, the ability to change the inner pattern easily and appropriately is very important in our rapidly changing environment.

A musician, a flautist for example, has no choice but to adapt to her instrument. The flute cannot change its weight or shape or manner of being played. Therefore the body has to adapt, tilting the head to the right, with the left arm carried to the right in inward rotation, and the right arm carrying the weight of the instrument in outward rotation. Furthermore, this position is maintained for many hours, and, even more importantly, with intense emotional concentration. The tendency to maintain the posture after the instrument has been put away is very strong, and produces a fairly predictable posture, with individual variations, of course. The author enjoyed a brief vogue with the London Symphony Orchestra members, and was able to surprise several clients with 'How long have you been playing the (violin, flute, cello, bassoon)?', before they had opened their mouths.

The trick of efficient postural adjustment is to have, be able to find, and actually employ, a neutral posture to which we return after an activity. The workman who stretches and groans as he straightens up is the simplest version, but it would be quite possible to teach a fairly sophisticated appreciation of one's own individual neutral posture, and how to find it. For instance, the author often pauses in the airport concourse to readjust his body into a good position for walking, the poor thing having been shaped by an aeroplane seat for the previous hours.

Besides instruments, car and 'plane seats, and computer workstations, we need to be cognisant of situations that shape us emotionally, and be able to reshape ourselves when the stress is gone. This is of particular interest in working just after the holiday season, when so many clients return 'wearing' the pattern they picked up during the holiday visits to their family of origin. This becomes a useful lesson for them in restoring a more authentic pattern, and in making an easy and conscious transition from one pattern to the other. It is important that, in the author's opinion, we not try to impose a 'proper' posture, but that we facilitate an easy adaptability.

This adaptability is based on the building blocks of our innate righting mechanisms, such as the labyrynthine, Asymmetric Tonic Neck Reflex, and the Landau reflexes, as evidenced by developmental movement studies, and employed so beautifully by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen in her Body-Mind Centering work (Cohen 1993). In the ideal world we are evoking here, teachers of 'Kinesthetic Literacy' classes would be able to recognize when these righting mechanisms are missing or out of order, and be able to take the students through movement sequences designed to restore or awaken them.

While Judith Aston's work (and the work of the Rolfing Movement Integration teachers; Bond 1993), as exemplified in the accompanying

JOURNAL OF BODYWORK AND MOVEMENT THERAPIES APRIL 1999

Myers

sidebar on the integrated use of the spine, concentrates on making conscious and cognitive postural adjustments and adaptations, Cohen's work involves seeing the underlying unconscious righting mechanisms at work below spontaneous movements. Through thorough training, practitioners can learn to recognize where these basic building blocks of good movement may be missing, delayed, or not integrated, in order to induce the proper mechanism through subtle movement re-training.

A simple example from nearly everyone's schooling is the postural adjustment most of us make to our standard issue desks. The author's experience is echoed by many of his clients: curled into whatever seat was allocated for the alphabetical roll call, our thoracic spines bent over the desk, and when called upon, we raised only our heads, putting a hyperextended neck over the flexed spine. Desks that are adjustable to the children, such as posturally-efflcient orthopaedic seats, would be wonderful, but are unlikely to arrive soon, given current school budgets. A brief lesson in adjusting yourself to the chair and desk - finding the comfortable seated posture, and using the spine as a whole in moving in a chair - is a cheaper alternative which might divert a lifetime of habit breath robbing (see Box 1).

Organismic response The interface between the animal within us and our beloved but ephemeral conceptual world has occupied philosophers for millennia. While manual therapy certainly does not have all the answers, it has formulated a different set of questions as well as the beginnings of an approach to practical ways of integrating body and soul, ego and id, or reptilian brain and neocortex, name the dramatis personae how you will.

Making friends with your animal

Living in an animal body in a 'civilized' society is a constant compromise. Our inattention to, and outright denial of, the animal nature at the 'heart' of our soma is a profound mistake at whose door can be laid huge social problems and a large part of the disease afflicting our population. First championed this century by Wilhelm Reich, the idea that we must find a positive outlet for the animal drives rather than repressing them in the service of society is a profound one with far-reaching implications for our educational system (Reich 1949). So much of our current social training is involved in pushing down the innate 'selfish' animalism of the body, it is no wonder that the joy and energy of the soma get such short shrift, or that physical manifestations of psychic repression show up so often in the doctors' offices and on our tables.

Physiologically, the see-saw balance between the 'sympathetic' and the 'parasympathetic' branches of the autonomic nervous system has tuned into a tug-of-war between the neuromuscular self and the visceral self. The 'fight-or-flight' response (which actually involves not only the sympathetic nervous system, but the entire neuropituitary-adrenal axis, or 'ergotropic' system; Gellhom 1964) activates our moving self, priming the newer neuromuscular body for action. This chemical, neural, and psychic charge is released by muscular action (often fighting or running, but it could be the sexual act or chopping wood and carrying water), and the system reverts to the 'rest-and-repair' side, the parasympathetic system, or more properly, according to Gellhorn, the entire 'trophotropic' system.

The problem is that our systems respond to both real and perceived threats. Since we are far more sensitive to our inner world than the outer one, we are capable of creating imaginary perceived threats to which there is no conceivable physical response, or to

which an appropriate physical response is out of the question as in the following example.

If Mr X is in competition with Mr Y for a higher position at the firm, he cannot, as a chimpanzee or a baboon might, thump Mr Y or beat him over the head. If he did, he would satisfy his own physiology, but he would not achieve his aim - he would be out on his ear or in jail. Instead, he can 'grin and bear it', which does nothing to dissipate the chemistry of sympathetic arousal, or he can practice 'displacement behaviour' by smashing a squash ball around, which will dissipate the chemistry, but does nothing to remove the stressor. Modern life is full of such disparities between the way our animal self would 'naturally' react, and how we have learned to act within a society (Sapolsk'y 1990).

Psychotherapy has sought to deal with the anxieties and neuroses that build up around these pattens of suppression. Manual therapy has as well, but pays less attention to the 'story' or content of the neurosis, concentrating instead on the somatic context, which expresses itself in habitual posture, styles of movement, and pattens of expression. Bridging toward the body from Gestalt Therapy, body-centered psychotherapeutic techniques, such as the Hakomi, the Rosen Method, or Somatic Experiencing, work with the somatic aspects of psychological disturbance and trauma resolution (Kurtz 1990, Rosen 1991, Levine 1997).

Most of these 'bioenergetic' approaches are indebted to Wilhelm Reich and his followers, such as Alexander Lowen and John Pierrakos (Reich 1949, Lowen), for identifying the basic body pattens of response to the disparity between the inner and outer world. Keleman took the idea one step further by positing how the generalized response pattens came out of the changing tonus and shape of the various tubular structures within the body (Keleman 1985). Both

JOURNAL OF BODYWORK AND MOVEMENT THERAPIES A P R I L 1999

Kinesthetic dystonia

Fig. 2 Bad full flexion pose with 'X'-chest behind the spine.

Fig. 1 Full flexion pose.

J O U R N A L OF B O D Y W O R K AND M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S A P R I L 1 9 9 9

Myers

Fig. 3 Good hyperextension pose.

Fig. 4 'Bad' hyperextension pose with 'X' - neck over extended. Fig. 5 Integrated sitting.

JOURNAL OF BODYWORK AND MOVEMENT THERAPIES APRIL 1999

Kinesthetic dystonia

further research and more social dialogue are needed in this domain. We require research to understand more completely the interaction among the central nervous system, the autonomic system, the hormonal/neuropeptide 'wash' of all systems, and psycho- neuro-immunology (Pert 1997). Ongoing social dialogues are underway already on what constitutes abuse, on gender differences, and on the productive expression of emotion.

Through close observation of the signs of autonomic activity - pupil dilation, skin colour changes, adrenergic and cholinergic sweating, peristalsis, breathing pattern, etc. - a bodyworker can follow the course of the sympathetic charge and discharge without reference to the content of the charge, in other words, without reference to the 'story'. In this way, bodyworkers and kinesthetic educators can be helpful psychosomatically without full psychological expertise, simply through their ability to follow and track the changing state of the autonomic balance and resolution within the client.

Could such a thing be taught? Can we teach children to track their own body process, so as to be able to spot their own 'angst' and nip it in the bud, temporarily control it as necessary, or follow it down to its roots? Can young people be taught to be emotionally autopoietic?

A number of possible assists in this direction come to mind. Apprising students of the existence and functioning of the underlying unconscious autonomic responses would be a start. If teenagers understood erections as well as they did condoms, we could avoid even more STDs and unwanted pregnancies. The understanding that unfinished emotional/autonomic business often involves an uncompleted motion was valuable to Nate (see Part 3A of this series, Myers 1999) as he assessed what was unfinished in his encounter with the bully.

For students to recapitulate animal movement gives an understanding of our underlying physical, emotional. and mental structure. The author often spends a day with his adult students to review the movements of life, beginning with the expansion and contraction of single-cell eukaryotes up through the arboreal hanging of the apes. Interacting with other students as animals from various rungs on the evolutionary ladder, students gain a sense of aff-mity with their biological history.

The ability to express emotions fully and authentically is a dream for most of us, and the teen years are fertile ground for such suppression or diversion of emotional energy. In addition, there are at least as many 'normal' human responses as there are animal types; the value is not to make everyone respond in the same way to a given emotional charge ('Thank you for sharing'), but to open the way to the authentic fulfillment of the organic self. The ability to contact one's animal self, even noticing a particular affinity for one animal over another, is a useful step toward making friends with the animal within.

Maturity Aside from the movements of the body in space and the movements within the body, there is a very slow but tremendously important movement that we bodyworkers have been known to assist: the movement toward maturity (Fig. 6). Everyone grows bigger, but not everyone 'grows up'. This lack of maturity has a Strong somatic component, and can occur in the body as a whole, or to just part of the body. To give some illustrations, imagine a boy of six lifting his arms straight up over his head. Do you see his shoulder blades sticking out to the side, the inferior angle out beyond his ribs? Probably you imagined it that way, because that is how immature shoulders work: the scapula tends to move in an arc that stays with the

humerus degree for degree. Now imagine an adult doing the same thing: most likely you imagine that the scapula stays more in place on the back of the ribs. In an adult, we expect the humerus to move through three degrees of arc for every one the scapula moves through. If we see an adult client coming through our doors whose scapulae are tied to the humerus 'like a child,' we can surmise that either: 1) an injury has linked the two, perhaps through tightening of the rotator cuff; or 2) the shoulders never developed out of that childhood pattern. They grew bigger, but they did not mature.

Another example came to our door recently: this client was a college professor, brilliant and accomplished in the academic realm. He was socially less adept, being selfish, needy, incapable in the larger world, so he had cocooned himself in the protective academic setting. He had a large round head, a short and rounded (as opposed to the more common elliptical adult) torso, shortish limbs, and turned out legs. When we stood him in front of a mirror to do our customary structural analysis, we realized that here was an infant body. This man never grew out of infancy in this movement toward maturity. He still responded like an infant to his surroundings, marrying a maternal woman and sheltering himself in an academic womb, still playing out his infantile responses even as his brain grappled with complex (and interesting and useful) biological problems. The ability to catch a body up on this decades-long movement towards maturity is a useful and unsung skill in the bodyv¢ork realm.

Like the inner pulsation of the visceral organs, this motion is too slow and subtle to be appreciated by its subject. A more detailed appreciation of the somatic maturation process in our PE system would allow us to recognize places in the body where the developmental shoe has been nailed to the floor, so that it can be released before it becomes irreparable. In our

J O U R N A L OF B O D Y W O R K A N D M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S A P R I L 1 9 9 9

Myers

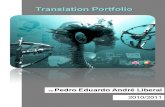

,!

B C

Fig. 6 One of the most interesting contributions bodywork can make to a new physical education is in the realm of maturational development. A, B & C show what can be accomplished: (A) Reginald before any bodywork, 03) after 10 sessions ofbodywork (under the direction of Dr Ida Roll), and (C) the right shows Reginald 1 year later with no further bodywork. The only modification in the pictures is to keep them the same size, while Reginald presumably grew.

In (A), Reginald shows a typical postural response of an anteriorly-tilted pelvis, a posteriorly-tilted rib cage, and an anterior neck, among other things. In 03), the post-Rolfing picture, he is demonstrably straighter, but not demonstrably better off. (In fact, one person, viewing these two pictures, said, 'you took away his naturalness and just gave him a weedy- white-boy posture! What good is that?) The third picture (C), however, tells a different story. With the weight of the shoulder girdle resting comfortably on the rib cage instead of hangfiag off behind it, the chest and the chest muscles are free to develop, so Reginald fills out, deepens, and looks a different boy. Our thesis is that Reginald, left to himself, would not have developed into the boy on the right in a year, but the boy in the middle could (and did). After the initial work, 'compound essence of time' was the only medicine necessary to do the job.

Being able to recognize such restrictions and realize such potentialities will be the job of both bodyworkers and physical educators in the coming century. (Reproduced with the kind permission of Robert Toporek and The Children's Project.)

experience, such work requires very precise and often body-wide work, and may not lend itself to educational methods, other than the usual rough and tumble o f hormones and experience that produces some semblance o f maturity in all o f us. Recognition o f the somatic dimension of maturity, however, would make

referral to a bodywork 'specialist' a more common event.

Kinesthetic sensitivity In this category goes all the cognitive teaching about the kinesthetic sense, o f how we sense ourselves and others, and what new skills we might be able

to develop through cultivating, instead o f systematically deadening, our kinesthetic talents.

Non-verbal communicat ion

So much emphasis is put on verbal communication in our schools, and so little on non-verbal communication. Yet the non-verbal underlies the verbal every time, and usually outdistances it in the amount of information conveyed. In working with couples, the author often asks one spouse to non- verbally cue the other spouse to do something simple, e.g., 'Without talking, get her to get out o f the chair and lie down on the other side o f the room.' How they go about it - both the guider and the guided - reveals the dynamics of the relationship more clearly and quickly than any verbal statement would do. Often, as well, one can work in this non-verbal arena without awakening all the defensiveness that usually comes up in verbal exchanges. Kinesthetic education can sneak in under the radar.

Children are generally very responsive when taught aspects o f non- verbal communication. Since so much of non-verbal communication is kinesthetic, we are really proposing making a curriculum out of kinesthetic skills. Since, as we have noted before, kinesthetic information can be transduced into behaviour 30 times faster than visual information, and many thousands o f times faster than audio information, leaving it out o f our curriculum is a waste. Imagine that you are trying to learn a new skill, from hammering, to getting on your own shirt the first time, a dance, or any physical skill. Someone could tell you about it, show you how to do it, or actually move your body through the motions involved. How do you think you will pick up the skill the fastest?

Theatre exercises and other games abound for teaching children o f all ages the rudiments o f non-verbal information, and how to read non- verbal cues. The techniques o f mime

J O U R N A L O F B O D Y W O R K A N D M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S APRIL1999

Kinesthetic dystonia

contain a rich set of conventions for non-verbal communication. The simple exercise of having children play with an imaginary ball, maintaining the concentration to see, feel, and follow the invisible ball simply through the movements of others, yields amazing results of group connection through non-verbal interaction.

Wide vocabulary of touch

Though not everyone will grow up to love or practice hands-on work, a vocabulary of touch is as basic to general education as a visual, mathematic, or linguistic vocabulary. Knowing how different types of touch feel, both as practitioner and recipient, would in one swoop change the 'feel' of an entire generation of schoolchildren. Short playshops in learning to 'wobble' each other fi la Trager, how to safely and efficiently guide each other in movement fi la Touch-in-Parenting, how to simply place the hands and see what there is to feel ~ la ReiN, how to use touch to calm the over-excited, how to restore or ease simple sports-related problems, even how to do basic corrective manipulations on each other/L la osteopathy - all of these are skills that are teachable incrementally, without much equipment, and in group situations.

Basic skills such as contact, body use, boundary and container issues - all the factors around touch that come up in bodywork schools - could be conveyed to the student population. Some students would take to these exercises like a duck to water, others might resent the whole thing and prefer 'Shop' or trigonometry, but it would do them no harm to be exposed to skillful touch. The question is rather what harm is being done currently in not exposing our students to simple touch. One basic result is a touch-starved population entering adolescence. Another result is a generation of teachers urged to refrain from touching their students, lest their gesture be

misunderstood. With so few in the society exposed to skilled touch, confusion abounds between sexuality, sensuality, and simple essential contact.

It is a standard lament that we require licenses for driving an automobile, but none for parents. Making sure that all secondary school graduates had at least some grounding in the basics of touch would not eliminate any jobs for hands-on therapists (quite the contrary, we expect), but would help to develop good parenting skills.

Sensitivity and intuition: the body as antenna

From Reiki, Shiatsu, and a host of other Oriental (and a few Occidental) approaches comes the idea of tuning the body's intuitional sensitivity. We tend to train children to tune out hunches in favour of facts. Bodywork teaches us to be exquisitely sensitive to fleeting and transient breezes that may signal the storms to come. Though the components of intuitional knowledge have yet to be categorized, it is empirically clear to many that the kinesthetic, especially the interoceptive, sense forms a large part of the basis for intuition. Our language is full of such indications: 'I felt it in my bones', 'It was a gut reaction', or 'My blood ran cold just to look at him'.

The writings of Dr James Oschman lead us toward considering the body, especially the fascial net, as antenna, and bodywork as a way of 'tuning' that antenna to different or more refined frequencies (Oschman 1997). Reducing the kinesthetic 'noise' to which we are subjected in our culture, returning to quietude and the natural world where possible, allows us to tune in to the more subtle signals our body can give us about ourselves and the world around us. Are humans capable of finding magnetic north without a compass? Of knowing what time it is without a watch? Of controlling

ovulation or other seemingly automatic functions? Anecdotes abound, but what are 'normal' human talents? How can we know when almost all humans are surrounded by electronic and literal noise at every juncture?

It is against the interests of an industrial society to train its children to be too sensitive, lest they become too sensitive to fit into the machinery of production, or equally into the machinery of consumption. The opposite begins to apply as we move into the post-industrial (we have, following Thomas Berry, named it the Eeozoic) era. Sensitivity will become the mainspring of human endeavour in the ensuing decades, and this is the educational gap we must close.

Children can be trained to be extra sensitive to the slightest changes of movement, as for instance in the sensory awareness exercises of Charlotte Selver (Brooks 1974). Traditional ensemble theatre exercises, such as those of Viola Spolin (1963), can be easily applied to school situations to increase sensitivity. For example, the author has found the following exercise fits both professional and young audiences: select one person to be the 'sculpture', and pair off the rest of the group. One member of each pair puts on a blindfold, this is the 'sculptor'. The other member of the pair is the 'clay' (for groups of more than 12 or so, create two 'sculptures'). Arrange the 'sculpture' into a complex but sustainable position; the person must stay in exactly that position for 5-10 minutes. The 'clay' person leads the 'sculptor' to the sculpture, and the sculptor registers the position of the sculpture only through kinesthetic feel. The sculptor then takes his clay a little bit away, and tries to reproduce the sculpture as exactly as possible in the clay. This must be done totally non- verbally, the sculptor is not allowed to 'talk' the clay into position, nor can the clay offer verbal advice to the sculptor. The sculptor can be led back to the original sculpture for a second feel,

J O U R N A L OF B O D Y W O R K AND M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S A P R t L 1 9 9 9

Myers

and then return to refme the position of the clay.

When the sculptor is finished, he or she can remove the blindfold and compare the original with the 'copy'. Be sure to call attention to small details such as hand or elbow position, medial or lateral rotation of the shoulder, spinal position. A roomful of these sculptures can often present quite a variety of interpretations of the original. After everyone has admired and critiqued everyone else's work, the sculpture and all the clay are gratefully allowed to move. Reverse roles and repeat.

Additionally, didactic and scientific knowledge is no enemy to sensitivity. It is difficult to be sensitive about something of which you have no picture. Especially for dominantly visual people, but for everyone to some degree, a filled-in three-dimensional grasp of the body allows students to be more cognizant of their internal process. We have already mentioned the sensitizing effect of building the muscles in clay onto the skeletal frame of Zahourek's Maniken (Myers 1999). Before being introduced to Barral's Visceral Manipulation work (1997), the author had no sense, beyond a general sloshing weight, of his organs and their attachments. Now, with a much clearer picture of how the organs are attached, it is much easier to appreciate interoceptively how they move, and how they pull on the locomotor structure as spatial position changes.

The pain-free body

Can anyone doubt that if we succeed in bringing these kinds of values into the educational system that we can bring about the goal of all our individual work, the pain-free body? The pain- free soma is free to sense the entire spectrum of what the world has to offer, to process it with the widest possible set of options, and to respond with the subtlest or most powerful actions. An educational system that

dealt more thoroughly with the kinesthetic system would lighten the burden of pain and its attendant fatigue and apathy.

The Eskimos have many words for 'snow'; we need more words for pain. Pain entering the body provides a warning. Pain stored in the body is sometimes felt as pain, but more often breeds a numbness that is felt only as fatigue or limitation. Pain leaving the body, as occurs in NeuroMuscular Therapy, Rolfmg, Yoga, or other therapeutic manipulations, is shunned by many as counter-productive, while in fact a momentary discomfort can be followed by pain-free inhabitance of a forgotten part of the body. While no programme can begin to remove pain or suffering from human experience, needless pain is a luxury we can well do without. Training the kinesthetic sense with even a tenth of the energy we put into teaching the visual and auditory senses would be well rewarded by surcease from the self- limiting cul-de-sac to which the end of the industrial era has brought us.

Summary The author welcomes comment on this initial attempt to set an agenda on applying manual therapeutic principles to Physical Education. New skills, tools, and insights (as well as revived ancient techniques) have developed within this field that have wide educational application. Furthermore, these tools are particularly adapted to the needs of the coming century. Opportunities abound for applying these insights educationally to more general populations than have been reached so far by individual practitioners doing one-on-one work in middle-to-upper class venues.

As 'Kinesthetic Dystonia' comes to be recognized as a societal misapplication of education, a synthesis of diverse bodywork and movement approaches will be applied to combat it. All the work we have done to date is valuable empirical

research; may we make the most of this opportunity for its wider application.

REFERENCES

Alexander F 1989 The Alexander Technique. Lyle Stuart

Alexander F 1928 The use of the self. Gollancz, London

Ban-al J 1988 Visceral manipulation. Eastland Press, Seattle

Barral J 1997 Manual thermal diagnosis. Eastland Press Seattle

Benjamin B, 1984 Listen to your pain. Penguin, New York

Bond M 1993 Balancing the body - a self-help approach to rolling movement. Inner Traditions, Rochester VT.

Brooks C 1974 Sensory awareness. Viking Press, New York

Cohen B 1993 Sensing, feeling, and action. Contact Editions, Northampton, MA

Crickmay M 1966 Speech therapy and the Bobath approach to cerebral palsy. Charles C. Thomas Ltd

Feldenkrais M 1972 Awareness through movement. Penguin, New York

Fuller B 1975 Synergetics. Macmillan, New York Gellhom E 1964 Motion and emotion, the Rolf

of proprioception in the physiology and pathology of the emotions. Psychological Review 71(7):457-472

Gellhom E 1978 Ergotropic and trophotropic Systems, p 13

CAndler E 1978 Gynmastik for busy people. Charlotte Selver Foundation Bulletin 1 (10), Caldwell, NJ

Hanna T 1988 Somaties. Addison Wesley, New York

Hunt V 1988 Study on spinal cord injury, p 5 Ingber D 1998 The architecture of life. Scientific

American, January: 4 8-57 Juhan D 1987 Job's body. Station Hill Press,

Barrytown, Vt Keleman S 1985 Emotional anatomy. Center

Press, Berkeley CA Kurtz R 1997 Body-centered psychotherapy. Life

Rhythm, Mendocino CA Laban R 1971 The Mastery of movement, 3rd

edn. Plays Inc, Boston Levine P 1997 Walking the tiger. North Atlantic

Books, New York. p 13 Lowen A Bioenergetics, Penguin, New York,

p 14 Maitland J 1995 Spacious body. North Atlantic

Books, Berkeley CA McAtee R 1993 Facilitated stretching. Human

Kinetics, Champaign IL Mehta S 1990 Yoga the Iyengar way. Dorling

Kindersely, London Myers T 1997 The 'anatomy trains'. Jottmal of

Bodywork Movement Therapies 1(2) Myers T 1997 The 'anatomy trains'. Journal of

Bodywork Movement Therapy 1(3)

J O U R N A L OF B O D Y W O R K AND M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S A P R I L 1999

Kinesthetic dystonia

Myers T 1999 Kinesthetic dystonia: the contribution of bodywork to somatic education'. Journal of Bodywork Movement Therapy 3(1) 36-43

Oschman J 1997 NORA, Box 5101, Dover, NH 0 3821,

Pert C 1997 Molecules of emotion. Scribner, New York

Reich W 1949 Character analysis. Simon & Schuster, New York

Rosen M 1991 The Rosen method movement. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley. p 13

Roth G 1997 Sweat your prayers. JP Tarcher, p 5 Sapolsky R 1990 Stress in the wild. Scientific

American, January, 16-22 Schultz L Feitis R 1996 The endless web. North

Atlantic Books, Berkeley, CA Spolin V 1963 Improvisation for the theater.

Northwestern University Press, Evanston IL Stirk J 1988 Structural fitness. Elm Tree Books,

London

Sweigard L 1998 Readings on the scientific basis of bodywork, energetic and movement therapies. Human ideokinetic Function. University Press of America, New York p 9

Todd M 1937 The thinking body. Dance Horizons, Brooklyn NY

Tzu-Yin S 1996 The basis of traditional Chinese medicine. Shambala Publications, CA, p. 6

Upledger J 1983 Craniosacral therapy. Eastland Press, Chicago

J O U R N A L OF B O D Y W O R K AND M O V E M E N T T H E R A P I E S A P R I L 1 9 9 9