Art of Fugue - Análise dos Temas

Transcript of Art of Fugue - Análise dos Temas

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

1/9

CAL PERFORMANCES

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS

Sunday, April , , pmHertz Hall

The Art of Fugue

Davitt Moroney, harpsichord

PROGRAM

Johann Sebastia n Bach () Te Art of Fugue,

Four Simple Fugues

Tree Counterfugue s in Stretto

INERMISSION

wo Double Fugues and wo riple Fugues

wo Mirror Fugues

Quadruple Fugue (completed by Davitt Moroney)

Harpsichord by John Phillips (Berkeley, ),after Nicolas Dumont (Paris, )

Cal Performances season is sponsored by Wells Fargo.

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

2/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

Johann Sebas tian BachTe Art of Fugue

Johann Sebas tian BachTe Art of Fugue

Fugue [on theArt of Fuguetheme].

Fugue [on theArt of Fuguetheme].

Fugue [on the melodically inverted version of the Art of Fuguetheme].

Fugue [on the inverted version of the Art of Fuguetheme, and a little cuckoo motif].

(on regular and inverted versions of theArt of Fuguetheme, combined)

Fugue [using two different versions of the Art of Fugue theme, (a) regular and (b) inverted; thesecond half presents them combined in strettos].

Fugue , in the French Style, by Diminution [using four different versions of the Art of Fuguetheme, (a) regular, (b) inverted; (c) regular, twice as fast, and (d) inverted, twice as fast. All versionsare presented combined in various strettos].

Fugue , by Augmentation and Diminution[using six different versions of the Art of Fuguetheme:(a) regular, (b) inverted; (c) regular, twice as fast, (d) inverted, twice as fast; (e) regular, twice as slow,and (f) inverted, twice as slow. All versions are presented combined in various strettos].

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

3/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

Fugue [using two themes, the first of which is new; the two are combined together in various ways,in Counterpoint at the th, so the lower theme can also be a fifth lower, or the upper theme afifth higher].

Fugue [using two themes, the first of which is new; the two are combined together in variousways, in Counterpoint at the th, so they ca n be doubled in thirds and six ths].

Fugue [three-voice triple fugue, on three themes, the first two of which are new and the third ofwhich is a rhythmic modification of the inverted version of the Art of Fuguetheme].

Fugue [triple fugue in four voices using the same three themes as Fugue , but not inverted; thistime theArt of Fuguetheme starts, in its regular form].

Fugue a[the first section is based on the main theme; the second section is based on the secondversion, an ornamented statement of the theme].

Fugue b[an exact mirror inversion of a, inverted top to bottom].

Fugue a[a three-voice counterfugue, using both the regular and inverted versions of a lively trans-formation of the main theme].

Fugue b[an exact mirror inversion of each individual part in a, but with the order of the parts juggled].

(completed by Davitt Moroney)

Fugue [quadruple fugue on four themes, the third of which spells out Bachs name and the lastof which is theArt of Fuguetheme].

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

4/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

is Bachs musical tes-tament. It gives tangible form to rhetoricalideas of exceptional nobility, partly by meansof an imposing musical architecture but evenmore by the warmth and richness of Bachsmusical imagination. In other words, the powerof Bachs intellect unpinned his extraordinarycapacity to use complex counterpoint for expres-

sive and emotional purposes.Te work lay unfinished at his death, with

pieces ( fugues and four canons), one ofwhich lacks its l ast page. Te surviving manu-script of the last fugue breaks off near the end.Scholarship has shown that somewhere between and closing measures a re now missing, butBach had no doubt brought it to full comple-tion in his mind. (Were they on a different sheetof paper, now lost?) Even more unfortunate isthe fact that his carefully planned scheme forTe Art of Fuguewas all but destroyed when thecollection was published, less than a year after

his death, by the addition of irrelevant pieces,and so there is now a severe confusion in theorder of works in the second half of the cycle (asexplained in detail below). Bachs scheme hasbeen restored relatively recently.*

Many conflicting ideas have been proposedabout this work. Tere has been so much non-sense written about it that even some of the cra-

ziest notions still need to be patiently dismissedand some of the most evident rational conclu-sions still need to be reiterated. Logical con-clusions will never convince people who preferto fantasize and leave aside rationality, so I donot quarrel with those who insist on having amythologized view of this work, any more thanI would with flat-earthers or creationists. Teworld of Bachs music has always been one whereirrational silliness coexists side by side with seri-ous reasoning based on evidence.

*My edition of the work is available as Die Kunst der Fugue, ed. DavittMoroney (Munich: G. Henle Verlag, ). Te intellectual under-

pinning of my edition drew notably on the scholarship of GustavNottebohm (), Donald Francis ovey (), Gustav Leonhardt(), R. Koprowski (), Wolfgang Wiemer (), and GregoryButler ().

When it comes to Te Art of Fugue, mostof the flat-earthers rely on pseudo-arguments.() Tis work, they say, was not written for anyspecific instrument. Reply: Such a belief ignoresthe evidence of Bachs , other works, alwayswritten ma gnificently and idiomatically for theinstruments chosen. Te work was understoodright into the middle of the th century to

be a keyboard work, and the idea that it is notone is just a th-century invention. () Tiswork can therefore, they say, be played on anyinstruments. My favorite recorded version inthis camp is the one on a saxophone quartet;there are versions for string quartet, full roman-tic orchestra, steel drums, synthesizer, and soon. Reply: Tis illogical leap ignores the realitiesof the keyboard features of the work and manyrefined details in the writing that Bach modi-fied in order to make it more easily playable bythe hands. () Tey claim that since Te Art ofFugue is counterpoint, the linear nature of themusic is better served when each line is playedby a different musician. Reply: Tis ignores theimmeasurable benefits for the counterpointwhen a single brain is in charge not just of playingall the parts but overseeing their exact harmonicand rhythmic interrelationships at all moments.() Tey point out that the open-score notationused for this work presents each melodic lineon a separate musical staff, proving it was notwritten for keyboard. Reply: Tis ignores Bachsown notational practice elsewhere for keyboardmusic, as well as the open-score notation pre-

ferred by most composers of serious keyboardcounterpoint over the previous years.() Tey sometimes claim that several soloinstruments can play certain f ugues faster thana single player can manage them. Reply: Tisignores the fact that Bach changed the level ofnotation for almost all the fugues originallynotated in th notes, but unfortunately he diedbefore finishing his notational revisions so hedid not apply the slower note values to the lastcouple of pieces. Tis means that some pieceslook as if they should be played fast but in factthey should not. () Finally, they claim trium-

phantly (when all other arguments fail) that inany case, it is impossible for ten fingers to play

Te Art of Fugue on a keyboard. Reply: Tisignores the fact that harpsichord keyboards aredifferent from piano keyboards; notably, theyare a little smaller and have a shallower key dip.Te perceived impossibility of certain pas-sages relates to a modern piano keyboard. (Andwhat do these people imagine ten-fingered harp-sichordists actually do when they play the work

in public? Whistle the notes they cant play?)One of the strangest claims about Te Art of

Fugueis that it is abstract, and should perhapsnot even be performed. Writers have waxed lyri-cal about how this is some kind of music of thespheres, perhaps best read from the page andnot heard as notes sounding in a performance.Such a view stems from a post-Romantic viewof counterpoint as something belonging to theworld of the intellect, and even as somethinganti-musical and anti-expressive. But Bachclearly liked keyboard counterpoint when it wasexpressed by ten fingers controlled by one brain.

He seems to have thought it was a good way ofwriting strong and expressive music.

Tere are also three fundamental practicalquestions that keep resurfacing. () Is Te Artof Fuguereally a harpsichord work? () In whatorder should the pieces be played? () Shouldthe famous unfinished fugue be consideredpart of the cycle, despite its being absent fromthe autograph manuscript and lacking the uni-fying motto theme that is common to all theother pieces? Extensive research by many dif-ferent scholars has now replied firmly to all

three questions. Newer research will undoubt-edly continue to shed light on these and otherpoints, but it is hard to see how the currentscholarly answers to these three questions willbe seriously contradicted.

Te questions are easy to answer. () Bachdid indeed specifically write the work thinkingprimarily of practical performance on the harp-sichord. Te entire work is playable by the tenfingers of two hands. Te open-score notation isa standard keyboard notation for counterpoint.Te top note (high e, found in fugue ) is ararity in Bachs works; it was available on harp-

sichords in the s but usually not availableon organs (whose top note was normally c or

d). Once it is accepted as definitely keyboardmusic, the question still remains: Which key-board? One feature in particular argues stronglyagainst Bach having conceived it with organprimarily in mind: the bass line in his big or-gan works always shows unmistakable signsof having been composed for the feet, not thefingers; those signs are entirely absent from Te

Art of Fugue. () For the printed edition (),Bach decided to change the order of the piecesby comparison with his autograph manuscript(ca. ); but the print was finally publishednearly a year af ter his death a nd unfortunatelyhis revised plan was not carried out correctly byhis executors. Fortunately, the intended ordercan be reconstructed without much room fordoubt. (See below for a more detailed discussionof this point.) () Any reconstruction of the ordermust indeed include the final unfinished fugue,since we now know that Bach allotted six pagesto it in his pagination scheme. Te absence of

the work from the main autograph manuscriptis a sure sign that it is one of Bachs very lastcompositions. As for the missing motto theme,it must have been scheduled to appear on thelast page, and needs therefore to form the cen-terpiece of any reconstruction of the last page.

I will stress here just a few features that particu-larly help listeners to Te Art of Fugue.

Inversion.An important part of Bachs lan-guage is the idea of turning a theme or melodicfragment upside down (known as melodic in-version). Te intervals are inverted (usually, butnot always, pivoting around the third degree ofthe scale). What went up, comes down instead.So a theme that sounds the notes D, E, F, G, Acan invert (pivoting around the F) to A, G, F,E, D. Bach uses this principle throughout TeArt of Fugue, announcing it right at the start, inthe first four pieces: fugues and are based onthe normal version of the theme, while and are based on the inverted theme. So in the motto

theme that unites all the pieces in the collection,D, A, F, D, C-sharp, becomes A, D, F, A,

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

5/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

B-flat when turned upside down. Teres noth-ing clever about this. Although the melody thuscreated has new pitches, the ear can easily recog-nize that the inversion is related to the originalform because the rhythm has not been altered,only the pitches. A normal version and its inver-sion will have identical rhythms. Even the inter-vals have not been altered, so an upward leap of

a fifth remains a fifth but leaps downwards, andstepwise motion remains stepwise. By the endof a concert of Te Art of Fugue, the listener hasheard the theme well over times, about halfin each direction, and often substantially modi-fied rhythmically.

Counterfugues. Fugues that systematicallyuse both melodic versions of the theme, normaland inverted, as known as counterfugues. In TeArt of Fugue,Nos. and are particu-larly elaborate counterfugues.

Stretto.Bach also often uses a device knownas stretto, especially in fugues . Te term is

close to the word Italians use for a dense coffeewith not too much water in it, ristretto, and inBachs music it means much the same thing; itcan certainly have a kick to it. In a stretto, themain melody is heard playing against itself inanother voice, so you hear the theme twice atthe same time, but with one part starting justafter the other. In other words, the theme har-monizes with itself in a sort of short canon. Temultiplicity and variety of the stretto treatmentin Te Art of Fugueis astounding, but also amus-ing. Fugue , in particular (where six versions

of the theme coexist in a joyous chaos, all tum-bling about and falling over each other), makesme think of a description of the Bach householdgiven by one of his many children. Te housewas always so full of children and other musi-cians running in and out that C.P.E. Bachdescribed it as being rather like a pigeon coop,with birds a lways flying in and out. Fugue isdefinitely a pigeon-coop fugue. Te four state-ments of the very slow version of the theme,grandfather-like (with the notes in rhythmicaugmentation), supports the whole structure,rising steadily through the four voices (bass,

tenor, alto, soprano), around which the normalversions of the main theme scurry about in every

direction, while the child-like fastest versions(with the notes in rhythmic diminution) rush allover the place.

Double counterpoint.In almost every pieceBach wrote there is more than one short mel-ody, and these melodies are combined togetherto make harmony. Te two-part Inventionsarein two-part counterpoint, always based on two

ideas being tossed back and forth between thehands. In two-part invertible counterpointalmost every melodic fragment found in onehand will appear somewhere in the other handwhen the counterpoint is inverted. Anymelodic passage can become the accompani-ment and any accompanimental passage canbecome principal melody. But the concepts ofprincipal melody and accompaniment arefundamentally misleading here. Tere is littlehierarchical distinction between melody andaccompaniment, since the whole point of theexercise is premised on their essential equality

and interchangeability.Triple counterpoint.In practice, Bach is at

his happiest when combining not two, but threethematic elements, in triple counterpoint. Tethemes are short, sometimes just one measureand rarely more than four measures. Althoughone theme is usually announced at the start ofa fugue (it is generally on the longer side andreferred to as the subject), it is not necessar-ily the most important melodic element in thework. Usua lly Bach combines the layers rapidlyby immediately adding a second theme in coun-

terpoint, and then a third, so that after about sixmeasures three different elements are already inplay together. Only then does the musical funreally begin; Bach juggles with his themes to findnew harmonies, like someone turning a three-dimensional object round to see new angles.

His contrapuntal language is usually com-posed within the particularly playful disciplinecalled triple invertible counterpoint. As itsname implies, this depends on there being atleast three melodic lines (called voices) in playfor most of a piece. riple because there arethree melodic elements; invertible because any

of these three lines can be on the top, on thebottom, or in the middle. Tis makes it sound

easy but is difficult to do convincingly, so thatthe result sounds natural. Without this invert-ible counterpoint, Bach would not be Bach; it isthe musical language that he speaks most com-fortably, the contrapuntal air that he breathes.One important feature of Bachian counterpointis his way of reinforcing the independence of thelines by making sure that they all have strong

rhythmic profiles, different speeds, and differentstarting moments. Te thematic threads rarelystart or end together, on the same beat, andthis feature helps him weave his lines into themusical texture.

Whereas double invert ible counterpoint caninvert into only one different position (sinceeither theme is on top and theme under-neath, or is on top and is underneath), tripleinvertible counterpoint is much more excitingand flexible, because the three themes can com-bine together in six, not two, different ways, andthus be superimposed vertically (harmonically)

in six positions. Anyone with an elementaryunderstanding of factorials, permutations, andcombinatorics will understand this point easilyenough. Tree factorialor ! to mathemati-cians; that is, xx=implies the six possibil-ities: //, //, //, //, //, and //.So four measures of carefully composed tripleinvertible counterpoint can generate for Bach,as he rings the changes, measures of excel-lent music. But since he also inverts the positionsand changes the keys (dominant, subdominant,relative major or minor, etc.), not only do the

harmonies sound quite different but the differ-ent versions are placed in different parts of thekeyboard, in new relationships with each other.

Although Bach generally likes to introducehis three melodic elements right at the startand move into the combinations as quickly aspossible, in some remarkable fugues he intro-duces them in distinct sections, at a consider-able distance from each other. After several longparagraphs dealing with the first theme (dur-ing which other melodic fragments are tossedaround in chatty invertible counterpoint), asecond theme is formally introduced. Te pur-

pose of such a scheme is to create a third sectionbringing together two themes which, until then,

have not met. Tese works are double fugues.Tey remind me of non-parallel lines. Tey startin different places, and at different angles, butwe know from the start that they w ill c ertain lyintersect. Part of the musical pleasure comesfrom finding out when and how this happens,and the fact that we are waiting for it.

Some such fugues even have three or (very

rarely) four separate themes, introduced at aconsiderable time distance from each other;these are all large-scale, highly imposing struc-tures, but the purpose is the same. Once theme has been introduced, it will be combined with; and after has been introduced, it will becombined with and . Tere is something su-perbly inexorable about the contrapuntal mech-anism behind these works. And of course Bachscompositional process in such cases will cer-tainly have started with the combinations thatonly appear at the end. From them he unravelsthe strands and weaves pages of extraordinary

music from each thread, before allowing thegrand combinations to crown the edifice. Workswith two themes are nowadays called doublefugues and works with three are triple fugues.

(Anyone with a taste for this kind of thingmight want to give a close listen to BachsCantata No. , Nun ist das Heil und die Kraft, ; it is a stupendous sextuple invertiblecounterpoint set into almost unstoppable com-binatory motion. Most listeners would neverknow its interior mechanism. It sounds joyful,strongly assertive, thrilling, and playful. Bach

must have had fun with it, and of course he doesnot use anywhere near all the possibilitiesoffered by the ! combinations....)

Understanding this combinatorial prin-ciple and learning to listen to more than onemelody at a time is perhaps the most fruitfulway of lea rning to appreciate Bach s music. Butother features can also be helpful. Tey tend tobe rather jargon-heavy, which is unfortunateand can be somewhat inhibiting. But the ideasthemselves are rather simple to understand andnot particularly difficult to hear. Te main pointof this fiery combinatorial part of his compo-

sitional process is to present his three melodicpartners, and to present them equally.

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

6/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and Berkeleysown Wurster Hall. I like to think of all thesebuildings as being rather fugal.

All of the musical matters I have men-tioned so far refer to musical structure and areessentially the composers business as musicalengineer. Or to take another metaphor, they arelike the ingredients that go into a cake, yet it

would be easy to make a bad cake with exactlythe same recipe. Bach pays great attention to thefreely created new melodies that are like the con-trapuntal icing on his carefully structured layercake. Writing in four parts using triple invert-ible counterpoint allows him always to have onefree voice with which to be inventive. Tis non-structural melodic material is present through-out Bachs fugues. o use a last analogy, it addsample and individualized flesh to Bachs skel-etal structural combinations. Playing fuguesand concentrating only on the themes is likebeing an expert chiropractor or surgeon rather

than an admirer of the warm beauty of a livingbody. Listening to (and playing) Bach fugueswhile concentrating less on the skeletal themesand more on the palpable melodic outbursts thatare not thematic can lead to a richer appreciationof Bachian counterpoint.

e fiery bits in-between. Bach has atrump card up his sleeve when using his con-trapuntal combinations so that these works(that could be rather intellectual bits of musi-cal engineering) avoid becomingto use hisown phraselike dry sticks. He wanted them

to have fire in them. He always develops thepassages where the main theme is not actu-ally being sounded anywhere (like the curvingarches between the solid pillars). Tese are whatEnglish-speaking musicians call episodes, butI prefer the French name, divertissements, a wordthat correctly implies that Bach, the player, andthe listeners are having fun. Bach called themthe Zwischenspielen , the bits played in-between.Tese free counterpoints, with their playfulinterludes, add not only fire but warmth tothe music.

Bach seems to have thought of the articu-

lation of themes alone as cold, dry sticks, andof the added free counterpoints as a warm fire.

Tere can be few approaches more destinedto kill young musicians appreciation of thenature of Bachs counterpoint than to encour-age them to bring out the theme by playingit louder. Te famous th-century musicalanalyst Hugo Riemann wrote (in his Catechismof Fugal Composition, ) that Bachs fugalwriting made possible the constructing of

longer pieces of compelling logic using only asingle theme. A more blind (and deaf) viewof Bach would be hard to imagine, and in factRiemanns own understanding of Bachiancounterpoint was more sophisticated than hisstatement implies; but not everyones is, espe-cially today. What made possible Bachs con-structing of longer pieces of compelling logicwas not the use of a single theme, but rat her themultiplicity of thematic material being used,constantly, in triple invertible counterpoint of arichly permutational kind.

A misguided stress on monothematic con-

struction is at the basis of most bad fugueplaying today. Each generation sees and hearsin Bach what it wishes to see and hear. Teobscurantism of Riemanns reductive formula-tion almost willfully obliterates the essence ofBachs counterpoint. Virtually none of Bachsfugues are based on developments of singlethemes. His works are full to the brim with oth-er fragmentary melodic ideas that get thrownaround in various combinations.

Nevertheless, the first four fugues of Te Artof Fuguedo not use these technical features, and

their restraint is precisely what is so remarkableabout them. Tey are composed on a theme thatwas deliberately designed to produce an extraor-dinary variety of strettos and inversions, yetthey studiously avoid contrapuntal fireworks,concentrating instead on pure, free counter-point. In these first four fugues, the themes aretherefore perhaps the least important element.

Free counterpoint. Fugues are complexstructures, but construction is not everything.How many people look at modern buildings andthink of the girders holding them up? Engineersand architects, perhaps. In some cases, impor-

tant features of the engineering are laid bare forall to admire, as with the Golden Gate Bridge,

Te way fugues are often played, I feel that thethemes are brought out rather like skeletalbones on an emaciated body. Te free counter-points are the beautiful, warm, living flesh andare more attractive; they can be the source ofmore sensual pleasures for players and listeners.Te sensuality of counterpoint depends on this.

Since the theme in a Bach fugue is precisely whatnever changes, bringing it out on the piano isessentially drawing attention to what is staticin the work rather than to what is constantlychanging. Bachs free counterpoints aroundthe themes, his flesh around the bones, is moreseductive and is constantly changing. I preferto concentrate on that, and to try and draw theattention of listeners to the most changing andimaginative part of a fugue, not to its stick-like

skeleton. And this is where the harpsichordcomes into its own. Pianos are capable of greatdynamic gradations; playing without using thatdynamic resource takes away something thatis fundamental to the inherent nature of theinstrument. Yet triple invertible counterpointdepends on all three melodic elements beingequal, as they get juggled in their permutationalshifts. In other words, the ways of making goodharpsichords expressive are in complete harmo-ny with the nature of the best music written forthem, but these expressive means are fundamen-

tally different from the ways of making goodpianos expressive. Te magnificent possibili-ties offered by the modern piano, including thekind of volume-by-touch, exist essentially in abeautiful parallel world that is largely irrelevantwhen playing Bach. When you t hink about it,triple invertible counterpoint is really a partic-ularly curious kind of musical style to try andplay on the piano, an instrument whose natureis fundamentally antithetical to the procedure.o make such counterpoint sound convincing,the piano has to give up much of what makesit a piano. Te ability to bring out one theme

means that players do in fact bring out themes.As with parents who unfortunately favor one

of their three children, the result is both unfairand unjust. Bachian counterpoint absolutelyrequires equality of treatment among thethemes, not bringing out one theme at theexpense of the others.

Tere are two common keyboard instru-ments that, by their nature, will always give fullequality to all simultaneously combined contra-

puntal themes: the organ and the harpsichord,because the players fingers cannot destroy or fal-sify the essential balance needed to present suchcounterpoint. Bachs keyboard counterpoint,with its constantly changing multiple combina-tions in every measure, grows from and dependson the fundamental nature of these two instru-ments. At first, they seem to be poles apart: theorgan has pipes and is a wind instrument wherethe notes do not decay towards silence as long asthe finger is playing the note; whereas the harp-sichord has strings that are plucked and do decayrelatively rapidly once the finger has played the

note. Te fact that Bach chose to write so muchof his highly expressive contrapuntal music forkeyboard instruments that cannot bring outnotes by playing them louder (rather than forviolins and flutes, for example) implies he wasnot at all bothered by the absence of this fea-ture. Since all his other music is highly expres-sive and emotional, his way of playing these twoobjectively less expressive instruments mustalso have been highly expressive; but it can onlyhave been so in a way that was radically differentfrom the kind of playing that is most natural to

a piano.Te period during which most of the fin-est contrapuntal music for keyboard was com-posed was the period when the harpsichord andorgan were the two principal keyboard instru-ments, so there is a chicken and egg situation.Did harpsichords and organs develop in the waythey did in the th and th centuries becausethe music that composers were writing wasessentially polyphonic? Or did composersdevelop their compositional styles for keyboardmusic because the instruments they had undertheir fingers responded in the way they did? Te

answer is that both are true. Te organ tracesits roots back many centuries; as a sophisticated

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

7/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

instrument with keyboards well adapted to thefingers, it dates back to at least the th century.Tat is also the time harpsichords first devel-oped in forms recognizably comparable to theones we know.

By Bachs time, these instruments hadalready had the benefit of a longer period ofdevelopment and a gradual process of perfection

that had lasted for longer than the entire his-tory of the piano until today. In other words,whatever relation the finest modern concertgrand piano has to the earliest pianos was moreor less the relationship that Bachs harpsichordsand organs had to the earliest known suchinstruments. Tere was nothing remotely primi-tive about Bachs instruments, or about his wayof playing them. By his time they had, for over years, been developed by wonderful crafts-men for superb keyboard players; they had beenimproved, in order to make them perfect forplaying the particular kinds of music that com-

posers wrote. Tat music was essentially poly-phonic and contrapuntal.

If both the complicated history of Te Art ofFugue and Bachs clear intentions are to beunderstood, some background knowledge is es-sential. During the s, Bach seems to havehad two overriding preoccupations: a desire topublish his keyboard music and a more private

interest in the expressive possibilities of intricatecanon and counterpoint. His publishing plansfor his organ and harpsichord music are easyenough to identify. He started with three vol-umes of Clavierbung, or keyboard practice: in, he published his six harpsichord Partitas,in a volume carrying the charmingly mislead-ing annotation Opus ; four years later, in, he issued the Italian Concerto and FrenchOuverture; and still four years later, in , hepublished a massive collection of organ pieces.In the last decade of his life, Bach moved intotop gear. Te fourth volume of Clavierbung,

the Goldberg Variations, appeared in ,followed in by the keyboard ricercars of

the Musical Offeringand the Vom Himmel hochvariations for organ, and in by the sixSchbler organ chorales. In the light of hispreoccupation with publishing some of his key-board pieces, we can see TeArt of Fugue,Bachsfinal summary of keyboard fugue, as a fittingclimax to years of activity, filling a gap in hispublished work that might have seemed strange

to his contemporaries since keyboard fugueswere one of the things for which he was mostfamous. (At this point he clearly still had noplans to engrave and publish Te Well-emperedClavier.) Te Art of Fugue was engraved, asWolfgang Wiemer showed, by J. H. Schblerduring the last year of Bach life. It was publishedonly in , a year after his death.

Bachs other preoccupation in his last de-cade, a private interest in strict fugal and canon-ic polyphony, comes to the fore in several ways.During the s, he had been putting togetherthe manuscript collection that would become the

second book of TeWell-empered Clavier(basi-cally assembled in ), but the works to whichhe then turned all had other features in com-mon as well as the contrapuntal intricacy. TeGoldberg Variations (), with their ninecanons (and their appendix of supplementarycanons, discovered years ago), the MusicalOffering (with ten canons and two exemplaryfugues), and the five canonic variations on VomHimmel hoch, all reflect Bachs increasing obses-sion with complex counterpoint, but each col-lection is also unified by a single key and is based

on a single theme. It is not surprising, therefore,that during the s Bach should have startedwork on a l arge-sca le s eries of fugues and can-ons (each one here called Contrapunctus byBach, a Latin name stressing the contrapuntallanguage of the fugue), demonstrating in a mag-isterial manner the expressive art of keyboardcounterpoint, but also presented with all theworks in the same key (D minor) and all con-structed on the same theme.

Te idea for such a work may have been slowlygerminating al l Bachs adult life, ever since ,the date of his famous visit to Lbeck, in order

to comprehend one thing and another about hisart (as he himself succinctly put it); the mirror

fugues are strikingly comparable to Buxtehudestwo four-part movements in D minor (eachalso entitled Contrapunctus and each hav-ing its mirror-like evolution), published in hisFried und freudenreiche Hinfarthin . Teseworks, composed in memory of Buxtehudesfather, may be the models for Bach mirrorfugues in D minor, entitled Contrapunctus

(Nos. and in Te Art of Fugue).It seems likely that Bach embarked on seri-ous work on Te Art of Fugueonly after finishingthe second book of Te Well-empered Clavier.Te sketches and autographs of the earliest ver-sions are lost. Probably in about or hemade an autograph score of all of the material hehad composed up to that point. Tis fair copydoes survive. It is in open score, with each ofthe four melodic lines on a separate staff, withall the notes designed to be played by the tenfingers of two hands. It contains twelve fuguesand two canons.

Tis total of may have been a deliber-ately self-referential gesture indicating Bachsown name, like a signature, since accordingto the age-old principle A=, B=, C=, etc.,B+A+C+H=. Bach was well aware of the factand exploited it in many ways. He added canons to the Goldberg Variations (endingwith etc., implying he could go on, but wasenough), and exploited both (=BACH) andits numerical reverse (=J. S. BACH) in otherworks. However, for Te Art of Fuguehe changedhis mind and added two more fugues and two

more canons, bringing the fugues themselvesup to and the canons up to four. Perhaps heintended to write a total of canons but wasinterrupted by the total blindness that causedhis final illness and death in July . (Te fourcanons are omitted in todays performance.)

His autograph manuscript contains manycorrections and modifications, including com-plete reworkings of two pieces (one fugue andone canon). Equally significant, at some pointBach took a critical overview of the inconsis-tent (and incoherent) notational levels he hadbeen using, and instructed his assistanthis

teenage son Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach()to double the note values for

several pieces in order to bring them in line withthe main notational level of the collection. Soseveral pieces originally written in eighth notesand th notes were renotated in quarter notesand eighth notes. (Modern players who misun-derstand Bachs purpose can easily unwittinglyplay these pieces at inappropriate speeds.) All ofthese corrections date from about , when

Bachs work was probably interrupted by hiscomposition of the Musical Offering and theVom Himmel hochvariations.

Tere is an additional element that shedslight on what Bach may have had in mind.In June he joined the Mizler Society, arather learned group of musicians, set up by hisfriend and student Lorenz Mizler. elemannand Handel were already members. Bach waitedto join until he could be the th member. Tiswas in all likelihood an in-joke, another refer-ence to his name. One condition of membershipobliged Bach to agree to submit a scientific

work, in published format, and it might havebeen the extremely complex six-part canon (sixparts derived from three different melodic lines)that is now associated with the appendix of canons added to the Goldberg Variations; heis shown displaying this complex canon in hisbest known portrait, painted by Elias GottlobHaussmann in ; we know the little canonwas printed since at least one copy of the originalprint survives. A further condition of member-ship in Mizlers society was that Bach shouldsubmit a new published work, in similarly sci-

entific vein, every year until the age of . Tiswas maybe his motivation for printing the highlycomplex Vom Himmel hochvariat ions () in ateasingly incomplete form visually, meaning theycannot be played directly from the publicationwithout first working out scientifica lly how toderive the missing canonic voices. In , Bachmay have offered his Mizler colleagues copies ofthe printed ricercars (very learned contrapuntalworks) from theMusical Offering; he printed copies but by October , , most of them hadbeen given away. It is possible, therefore, thatBach thought of the printed edition of Te Art of

Fugueas being his final offering to the membersof the Mizler Society, probably intended as his

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

8/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES

gift; after March he would be off thehook, since he would have turned .

However, things did not quite turn out asplanned. By mid- Bach had already gone

blind and his work on Te Art of Fuguegroundto a halt, despite the help of young JohannChristoph Friedrich. Te first part of the collec-tion (comprising the first ten fugues) was sent offto the engraver and corrected; we are thereforefairly sure about what Bach intended for theseten fugues. Among them were at least one newfugue (No. , not found in the autograph manu-script) and one heavily revised fugue (No. ,which was given a completely new opening).He was probably able to check and correct theengraved plates for these pieces. By June ,however, his eyesight (which had always been

troublesome) had deteriorated badly, due to acataract, and he could hardly work at all. Bachshealth was cause for such general concern thathis employers actually auditioned his successorat that time, so sure were they that he was aboutto die.

He rallied, however. Although almost to-tally blind at times, he continued work, dic-tating revisions of existing works (and perhapssome final compositions) to those of his youngersons who were still living at home. It was prob-ably at this point that he was able to put fugues

in order and start work on the concludingfugue, No. . At the end of March , he hada painful eye operation. Death finally came onthe evening of July , , following a st roke.

No one seems to have known precisely whathis intentions were. At the time of his deaththe corrections to the second half of the col-lection had not been carried out. Te remain-ing pages were hastily engraved. Te inventoryfor Bachs estate lists a small payment due toMr. Schbler; since this was equivalent toless than the value of Bachs two dozen pewterplates, it seems unlikely that very many pages

remained to be engraved on the metal plates thatwere used for printing at that t ime.

Te Bach family (probably with C.P.E. Bachmaking the decisions, and making the mis-takes) found themselves in a difficult spot. Teytried to finish the work on the edition, perhapshoping to raise some money. (Bach did not diea wealthy man, and his widow was soon des-

titute.) In their confusion, they misguidedlyplaced the last fugue (No. )which was in-completeat the end of the volume, after thefour canons. Gregory Butler has convincinglydemonstrated (using infrared photography ofthe page numbers, which have been altered) thatBach originally allowed the six pages follow-ing fugue No. for this last fugue. His studyshould therefore have laid to rest the erroneousidea that Bach did not intend the unfinishedfugue to form part of Te Art of Fugue(an ideaunfortunately supported by certain earlier writ-ings by Gustav Leonhardt).

Bachs sons were in no doubt that it belongedwith the collect ion; their only doubt was whereto place it. Butler has not only shown they wereright to include it, but also confirmed the fuguescorrect place in the cycle. (ovey had, in ,already proposed that it should be positioned asfugue No. .) Te familys decision to place theunfinished fugue (the surviving portion of whichoccupies only five, not six, engraved pages) atthe end of the whole work was very unfortunate;this created a six-page gap in the paginationbetween the end of No. and the first of the

four canons. Tey filled this gapthereby sow-ing the seeds of immense confusionby add-ing the three-page early version of fugue No. and by displacing the three-page fourth canoninto first position. In this way, Bachs inheritorscommitted a series of simple but fundamentalblunders that have plagued Te Art of Fugueever since.

() Tey included an early version of a fuguethat had already been engraved and printed asNo. . In revising that fugue, Bach had added measures to the opening and had made innu-merable corrections to the rest of it. Tere can-

not be any question of his having intended theearlier version to be printed.

() Tey changed Bachs logical musicalorder of the canons. Te fourth canon is themost complex (at the interval of the fourthbelow, by augmentation and inversion) and itscomposition gave Bach much trouble, as weknow from his earlier drafts. By placing thethree-page fourth canon in front of the threerather simpler two-page canons, they destroyed

something important in the musical structure ofthe group.

() Tey robbed the great unfinished fugueof its rightful place as the climactic th fugue.Tis is the piece whose third theme is derivedfrom Bachs own name. BACH in Germannotation spells out the chromatic theme B-flat,A, C, B-natura l. It is thus t he la st new themeintroduced into the whole of Te Art of Fugue.It cannot be a coincidence that Bach introduceshis melodic signature precisely at the end offugue No. , since is also the number equiv-alent of the letters BACH, as mentioned above.

Following these errors, the family commit-ted two more, by including other pieces thathave no place in the work.

() Tey included two arrangements of thethree-part mirror fugue (No. ), as reworkedby Bach for two harpsichords, in four partsand they even managed to print them in thewrong order! Tese arrangements have no logi-cal place in Bachs tightly constructed cycle offugues. Te error is understandable, since thearrangements are based on the motto theme andtherefore seem at first glance to be part of the

collection. Bach made many such transcriptionsduring his lifetime; one movement for unaccom-panied violin was transcribed for full orchestra(including organ, trumpets, and drums), andothers were arranged for harpsichord; this doesnot mean that the transcriptions belong with theset of works for unaccompanied violin. In thecase of the two arrangements of fugue No. ,both pieces make fine works for two harpsi-chords, but this does not alter the fact that theoriginal three-part version makes a splendid pairof mirrored pieces for solo harpsichord. It is thethree-part version alone that belongs with the

Art of Fuguecycle.

() Finally, and most surprisingly, theyadded at the end of the volume the complete-ly irrelevant organ chorale prelude Wenn wirin hchsten Nten sein. Tey explained in anexplicit apology that the chorale was offered asa sort of compensation for the incompleteness ofthe last fugue.

In short, the family not only displaced two

works (the th fugue and t he first canon) butalso added four movements that do not belongto the printed cycle of Te Art of Fugue.

Bachs revised scheme for the work is simple.It consists of fugues built on the same theme(or on transformations of that theme), organizedin two groups of seven. Tey are arranged inorder of increasing complexity. In the firstgroup, there are four simple fugues followed bythree inversion fugues (contrafugues) in stretto.In the second set, there are four fugues on twoor three themes (Nos. ), two mirror fugues(each presented first in normal version then

repeated in its mirror version), and a concludingfugue on four themes, one of which was Bachsown name spelled out in musical notation, as afitting signature to the whole. o this principalscheme he added, as a sort of appendix, fourcanons built on the same theme and similarlyintended to be placed in order of increasingcomplexity. (Tis structure is restored in my edition for Henle Verlag.)

A further word is necessary concerning my com-pletion of fugue No. . As with almost all ofthe problems associated with Te Art of Fugue,Bachs intentions can be deduced and a comple-tion of the fugue can be proposed without muchdifficulty. Gustav Nottebohm was the first topropose (over years ago) that, although thefugue has three separate themes and was giventhe title Fuga a Soggetti in the posthumousedition, the completion planned by Bach musthave introduced the motto theme. Tis idea hasbeen attacked as often as it has been defended.

I side with Nottebohm (and with ovey and

-

7/25/2019 Art of Fugue - Anlise dos Temas

9/9

CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES

ABOU T TH E ART ISTPROGRAM NOTES

many others). Since we now know that thisfugue was indeed intended to follow fugueNo. , the completion mustcontain the mottotheme, like every other movement in the collec-tion. Te titles reference to fugue with threesubjects means nothing, since it was almostcertainly added (by C.P.E. Bach?) after Bachsdeath. All of Bachs own titles in this collection

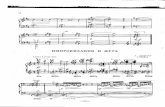

are in Latin, not Italian. ovey noticed, in a par-ticularly intelligent observation, that the mottotheme supplies the missing rhythmic link whenall four themes are combined (the quarter notesof the motto fill in the single passage wherethere is a rhythmic vacuum in an otherwiseseamless flow of notes; see the musical exampleon page ). He here drew attention to a highlycharacteristic feature of Bachs counterpoint.

Since Gregory Butler showed that Bachallowed six pages for the fugue, and since thesurviving portion already occupies five, Bachsplanned completion cannot have contained

more than about measures (assuming thesixth page to have been full). I have constructedby -measure completion around the only twousable statements of the final combination ofall four themes. (I mean usable in the senseof playable by the ten fingers, like the rest ofthe work.) I give the first combination in G mi-nor with the motto theme in the soprano voice,because the introduction of Bachs own name,starting on a B-flat, pushes the music towardsthe subdominant; and I give the second in thetonic, D minor, with Bachs own name in the

soprano voice, since he seems to have wanted tosign the whole work with his name. I have linkedthese two statements with a three-part stretto onthe B-A-C-H theme; this triple stretto has notyet been used by Bach but he was undoubtedlyaware of it (and even hints at it); I assume he wassaving it for the last, climactic episode, so that iswhere I place it.

Te music of these three portions of mycompletion, like three large bricks making upnearly measures, can be said without undueexaggeration to be more than mere speculation.Te cement I have added around these bricks

is designed to maintain the wild chromaticismthat Bach himself unleashed with his musical

signature theme. I have refrained from indulg-ing in a final tonic pedal, following the exampleof fugues Nos. and , the longest completefugues in the cycle. Comparison with the six-part ricercar from theMusical Offering, itself oneof Bachs grandest fugal constructions, is helpfulhere. By , Bach wa s more interested in con-cision than in lengthy perorations. (Just for the

record, my last measure is a deliberate referenceto fugue No. , a fugue I particularly like.)

Davitt Moroney

D was born in England in. He studied organ, clavichord, andharpsichord with Susi Jeans, Kenneth Gilbert,and Gustav Leonhardt. After studies in musicol-ogy with Turston Dart and Howard M. Brownat Kings College (University of London), heentered the doctoral program at UC Berkeley in. Five years later, he completed his Ph.D.

with a thesis, under the guidance of JosephKerman, Philip Brett, and Donald Friedman,on the music of Tomas allis and WilliamByrd for the Anglican Reformation. In August, he returned to UC Berkeley as a facultymember and is a Professor of Music as well asUniversity Organist.

For years he was based in Paris, work-ing primarily as a freelance recitalist in manycountries. He has made over CDs, espe-cially of music by Bach, Byrd, and Couperin.Many of these recordings feature historicth- and th-century harpsichords and

organs. Tey include Bachs French Suites(two CDs for Virgin Classics, shortlisted forthe Gramophone Award), Te Well-emperedClavier (four CDs), the Musical Offering, thecomplete sonatas for flute and harpsichord, andfor violin and harpsichord, as well as Te Art ofFugue (a work he has recorded twice; the firstrecording () for Harmonia Mundi France,received a Gramophone Award; the second re-cording () accompanies the edition of TeArt of Fuguepublished by ABRSM Publishing,London). He has also recorded Byrds complete

keyboard works ( pieces, on seven CDs, us-ing six instruments), and the complete harpsi-chord and organ music of Loui s Couperin (sevenCDs, using four instruments). His recordingshave been awarded the French Grand Prix duDisque(), the German Preis der DeutschenSchallplatenkritik (), and three BritishGramophone Awards (, , ). For hisservices to music he was named Chevalier danslOrdre du mrite culturel by Prince Rainier ofMonaco () and Officier des arts et des lettresby the French government ().

In , he also published Bach, An

Extraordinary Life, a monograph that has sincebeen translated into five languages. In spring

, he was visiting director of a researchseminar in Paris at the Sorbonnes cole pra-

tique des hautes tudes. His recently publishedresearch articles have been studies of the mu-sic of Alessandro Striggio (in the Journal of theAmerican Musicological Society), of FranoisCouperin, of Parisian women composers underthe Ancien Rgime, and a more personal articleon the art of collecting old music books.

In , after tracking it down for years,he identified one of the lost masterpieces of theItalian Renaissance, Alessandro Striggios Massin and Parts, dating from , thesource for which had been lost since . He

conducted the first modern performance of thismassive work at Londons Royal Albert Hall inJuly (to an audience of , people, and alive radio audience of many millions of listen-ers) and conducted two performances at theBerkeley Festival & Exhibition in June .wo further Berkeley performances took placein February , for Cal Performances (TePolychoral Splendors of Renaissance Florence),and included first performances since the thcentury of other newly restored mega-worksby Striggios contemporaries. He has recentlyrecorded the sixth CD of his set of the complete

harpsichord works of Franois Couperin (tenCDs for the Plectra label).

ScottHewitt