Architecture Macau | am N17

-

Upload

architecture-macau -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Architecture Macau | am N17

1

2

15

27

39

13

25

37

16

28

40

14

26

38

12

24

36

5

17

29

41

3

6

18

30

42

7

19

31

8

20

32

9

21

33

10

22

34

11

23

35

4

EDITOR EDITORRui Leão

ASSISTANT EDITOREDITOR ASSISTENTEHo Pui Kei

EDITORIAL COMITTEECOMISSÃO EDITORIALNuno Soares, Ryan Leong, Rex Ng, Eliezer Villaruz

ADVISORY BOARDCONSELHO REDACTORIALEddie Wong, Carlos Marreiros

ART DIRECTIONDIRECÇÃO ARTÍSTICARui Leão & Luís Almoster

GRAPHIC DESIGN & PRINTSHOP PRODUCTIONDESIGN GRÁFICO E CONTROLO DE TIPOGRAFIACan Design

CONTRIBUTORSCONTRIBUIDORESCarlotta Bruni, Murillo Marx, Cristina Veríssimo, Joy Choi, Vincent Kong, Donna Wu, MAM, FUPAM

TRANSLATIONSTRADUÇÕESHo Pui Kei, Ryan Leong, Nice Language Services Ltd.

ADVERTISING AND SECRETARYPUBLICIDADE E SECRETARIADODulce Amores

PRINTINGIMPRESSÃOTipografi a Welfare

www.cialp.org

Cov

er p

hoto

: Nun

o S

oare

s

5

As cidades Asiáticas e o Património

Carlotta Bruni*

Carlotta Bruni*

Enquanto Arquitectos, falamos sobre espaço e a espacialidade destinada a desempenhar funções específi cas. Falamos sobre edifícios que, devido à sua essência tipológica uni-versal, têm conseguido, ao longo dos anos e dos séculos, desempenhar diversas funções, desde conventos a universidades, desde palácios a museus e por aí adiante.

A minha herança cultural requer uma dimensão religiosa relativamente à forma, relacionada com a função, e relativamente ao génio loci do local e da sua arquitectura.

Apesar de estar habituada a ambientes onde tudo acontece em uníssono desde uma tenra idade, acho que Macau é irresistível pela sua cacofonia, que me faz lembrar uma sinfonia contemporânea, ao jeito de uma experiência do Italiano Luciano Berio.

Pessoalmente, acho que os desenvolvi-mentos aleatórios das cidades do Sudeste Asiático são muito interessantes, porque me sinto constantemente à beira de descobrir algo completamente novo, apesar de, fre-quentemente, ser impossível identifi car as

expressões fundamentais de uma qualquer estratégia de fundo.

No que respeita ao Património, e respec-tiva gestão numa cidade contemporânea, é evidente que Macau atravessa uma fase confusa, porventura ignorante, relativamente ao signifi cado e meios de preservação da sua excepcional herança cultural. Isto torna-se evidente pela contínua secundarização da sua mais específi ca característica: o ante literam próprio de uma cidade cosmopolita. Esta se-cundarização acontece quer por negligência

ESSAY

6

quer por uma falha de interpretação da sua herança arquitectónica e humana e, pior ainda, por uma falta de desejo relativamente a ela.

Trata-se de um assunto delicado, uma vez que, para um Europeu, falar sobre conservação no Extremo Oriente signifi ca reconhecer a existência de out-ras soluções para um mesmo problema e, portanto, valores diferentes relaciona-das com Pedras e Palácios.

Na Europa, fascinam-nos de tal modo as dimensões românticas da História que ocorreu uma enorme polémica à volta da renovação dos fres-cos da Capela Sistina no Vaticano.

Quando o tom escuro e sombrio das pinturas – resultado de séculos de exposição ao fumo das velas -, foi retirado, sentimos a falta da pedra an-gular que inspirou gerações de artistas românticos, nomeadamente aquela que costumava ser a assustadora cena do Juízo Final.

Sentimos uma quebra na corrente cultural, apesar de podermos agora apreciar as cores serenas de um Miguel Ângelo que ainda não conhecíamos.

A antinomia étnica que envolve esta situação é um paradigma: é mais importante restaurar uma obra e fazê-la regressar ao seu estado original ou assumir que, essencialmente, o valor da produção humana reside no seu con-fronto com o Tempo e na forma como foi encarada durante a História.

Da mesma forma, durante o Ren-sacimento, assumiu-se que a arquitec-tura e escultura Gregas eram feitas em mármore branco, mas sabemos agora que não era assim, já que os edifícios e as estátuas eram pintadas.

Se este conhecimento fosse público no século XV, talvez não tivéssemos disfrutado a pureza espacial da Capela Medici e as formas do David de Miguel Ângelo que conhecemos hoje.

No nosso contexto cultural contem-

porâneo, é moralmente proibido reconstruir um estilo que foi afectado pelo Tempo. O nos-so dever é limitado a tomar conta de ruínas que, por si só, são reservatórios de cultura.

No Oriente, nunca seria uma coluna

7

de madeira a mensageira de mil anos de história, mas a sua intenção, a forma dessa coluna que foi substituída mil vezes para preservar o seu conceito. O tempo não é uma força activa, no limite radical da inven-

ção de parques de Património.Durante uma viagem a Tóquio, dei por

mim sentada no salão de entrada do novo Imperial Hotel a sentir a falta de não poder observar os espaços traçados com a mestria

de Frank Lloyd Wright. Descobri então que a arquitectura do hotel tinha sido parcialmente transferida (nas palavras de um recepcionista do hotel) para um Parque Temático da Era Meiji, situado em Meiji Mura.

Nesse parque, os turistas podem pas-sear e apreciar, num cenário presidido por um lago, cada uma das valiosas peças arquitec-tónicas destruídas durante o período Meiji.

O Património parece não caber no desen-volvimento económico de uma cidade Asiáti-ca. Provavelmente, a arquitectura comum nas cidades Asiáticas não é sufi cientemente ªricaª para ser reciclada e utilizada para outros fi ns, ou então, os cidadãos não partilham a con-sciência e o prazer que nós sentimos quando vivemos numa zona histórica. A legislação que regula e protege o património pode ser demasiado frágil para suster a pressão dos preços nos centros urbanos.

Ainda assim, existem algumas excepções, onde a interacção entre os regulamentos gov-ernamentais e projectos de desenvolvimento devidamente proporcionados resulta numa in-teressante mistura de património e nova urban-ização, como é o caso de Quioto, Singapura e algumas partes de Xangai.

Em Macau, o património é ainda um fardo e raramente um valor.

Alguns edifícios foram transformados em departamentos públicos e algumas ªilhas históricasª ainda merecem uma visita. Alguns edifícios privados foram intervencionados segundo a simples fórmula de manutenção da fachada original à frente de um edifício novo e totalmente desproporcionado.

Independentemente de se falar de uma manutenção conservadora das suas pedras ou da manutenção de um local tal como foi originalmente concebido, trans-ferindo pedaços de património para locais próprios onde turistas podem apreciá-los ou deixando-os fi car onde originalmente estavam e assim permitir o confronto com a cidade contemporânea, devemos seguir um desejo claro de integrar esses vestígios patrimoniais na parte mais activa das nossas actividades sociais. * Arquiteta

8

As Architects, we talk about space and spatiality destined to specifi c functions and of buildings that, given their universal typological es-sence, through the years and centuries have the ability to carry out diverse functions, from convents to universities, from palaces to muse-ums and so on.

My cultural heritage asks for a religious aspect towards form, related to function, and the genius loci of place and its architecture. Although being used to environments where everything plays in unison from a tender age, I fi nd Macao irresistible for its cacophony, which reminds me of a contemporary symphony, like some experiments by the Italian, Luciano Berio.

Personally, I fi nd the random developments of South East Asian cities very interesting, because I feel like always being on the verge of discovering something absolutely new, although frequently, it is impos-sible to trace the fundamental expressions of an underlying strategy.

Concerning Heritage, and its management in the contemporary city, it is quite clear that Macao is going through a phase of confu-sion, if not ignorance, towards the means and purpose of preserving its exceptional cultural heritage. This is evidenced by the continuous demeaning of its most specifi c character: the cosmopolitan city ante literam, both by negligence and misinterpretation of its human and architectural heritage, and even worse, for a lack of a desire towards it.

This is a sensitive issue, since for a European to talk about con-servation in the Far East means recognizing the existence of other so-lutions to the same problem and so, different values related to Stones and Palaces.

In Europe, we are fascinated by the romantic dimensions of his-tory, to such an extent that a huge polemic was raised around the renovation of frescos in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel.

When the dark and obscure character of the paintings resulting from centuries of exposure to candle smoke, was withdrawn, we felt the loss of the corner stone that inspired generations of romantic artists, namely what used to be the terrifying scene of the Final Judgment.

We felt the break of cultural chain, even if we can now enjoy the original serene colours of a Michelangelo that we didn’t yet know.

The ethnic antinomy lying underneath is a paradigm:

is it more important to return the work to its original form or as-sume that the value of a human production par excellence, lies in its confrontation with Time and the way it was looked at during history.

In the same way, during the Renaissance, it was assumed the Greek architecture and sculpture were marble white, which, as we know now is fake, as both these buildings and statues were fully painted.

If this was known or a prevailing fact in the quattrocento, we might not enjoy the spatial purity of the Medici Chapel of the forms of David by Michelangelo as we do today.

In our contemporary cultural framework, it is morally forbidden to rebuild in a style that was ruined by Time. Our duty is narrowed down to taking care of the ruins, by itself which is already a container of culture.

Freezing the heritage in our time by simultaneously not letting Time ruling it and neither simulating its initials state circumscribes its enjoyment to a voyeuristic perspective.

In the East, it will never be the wooden beam which carries a thou-sand years of age, but the intention, the form of that same beam, that has been replaced a thousand times, so that its concept can remain unchanged. And Time isn’t an active force, to the radical extent of the invention of Heritage parks.

Once on a trip to Tokyo, sitting in the lobby of the new Imperial Hotel, I felt the loss of never being able to set my eyes on the masterly traced s[aces of Frank Lloyd Wright, when I discovered that the same architecture had been transferred (in the words of the concierge) par-tially to a thematic Heritage Park of the Meiji Era, in Meiji Mura.

There are the tourists could stroll and enjoy, in a lake setting, each valuable architectural piece wrongly destroyed in the Meiji period.

Heritage does not seem to fi t in the economical development of the Asian City. Probably the common architecture in Asian cities is not “rich” enough to be recycled for different uses, or the citizens do not share the consciousness and pleasure, as we do living in an histori-cal neighborhood. The regulation concerning and protecting heritage might be too weak against the land price of city centres.

There are few exceptions though, where government regulations blended with properly scaled developments achieved an interesting mixture of heritage and new development, as in Kyoto, Singapore and some parts of Shanghai.

In Macao Heritage are still a burden, and hardly a value.Here, some buildings have been converted into public bureau and

some “historical islands” are still worth a visit, some privately owned buildings have been revamped in the very simplistic formula of an old façade-framed-under an-out-of-scale-curtain-wall-hat.

Whether speaking of conservative renewal of its stones or the maintenance of the place as it was originally conceived, transferring pieces of heritage to proper places for tourist enjoyment or keeping it in the place which the primitive intention had chosen and permitting it to confront with the contemporary city, in either case we should follow a clear desire to incorporate the remains of our heritage to the most lively part of our social activities.

Heritage

Carlotta Bruni*

* Architect

and the Asian Cities

ESSAY

9

10

11

12

O calado dos navios aumentou muito durante o último pós-guerra. Depois dos grandes porta-aviões e superpetroleiros, surgiram imensos porta-contêineres e os cruzeiros para turismo. Exigem estes maior profundidade das águas para acesso e acostamento dos avantajados cascos, que deslocam a céu aberto uma miríade de recipientes modulados ou de cabines, suítes e dependências para passageiros.

O calado ditaMurillo Marx

Palestra proferida no Seminário “Cidade – Cultura - Ambiente”

Uma nova arquitetura naval quase sem castelo ou quase somente castelo. Nos tem-pos modernos europeus fora fácil identifi car a evolução da silhueta das embarcações pelos cascos, castelos e mastros. Ao insinuar apenas um à popa nos quinhentos, os dois castelos seiscentistas, sua redução ou mesmo desapa-recimento nos setecentos; paulatina evolução para enfrentar o mar grosso...

13

Em memoria do Professor Murillo Marx, convidado de honra e orador no seminario do XII encontro

do CIALP, Macau 3-5 de Dezembro 2010

MURILLO MARXArquiteto e Professor Titular da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo. Dirigiu o Serviço de Defesa do Patrimônio Cultural da Cidade, do Estado de São Paulo e da Universidade de São Paulo. Nesta Universidade foi Vice-Diretor, Diretor do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros e do Museu de Arqueologia e Etmologia. Autor de Cidade brasileira, Nosso chão: do sagrado ao profano, Cidade no Brasil: terra de quem?, Cidade no Brasil: em que termos?, e South American colonial art.

Dada a situação geográfi ca conveniente para o estabelecimento de um porto, o calado ditava certamente a escolha do sítio urbano adequado. A navegação marítima, lacustre ou fl uvial comprova esta condicionante para a ori-gem e para o desenvolvimento dos portos desde os tempos mais remotos e por todos os mares, lagos e rios do planeta.

De lembrar pelo sítio preferido Cartago, Lucerna e Sevilha em momentos tão distintos e, no mundo português, Goa e Macau ou, bem antes Viana do Castelo e bem depois a sulameri-cana Porto Alegre. E nelas acompanhar também os seguidos desafi os para a sobrevivência de uma relação profícua e dinâmica entre os seus respectivos embarcadouros e tecidos urbanos.

Com a revolução industrial sobrevêm mudanças na construção naval e novas im-posições para os portos e, progressivamente, sobre a própria ocupação e uso do solo urbano. O cais de acostamento se difunde para receber igualmente algum maquinário pesado e longos armazéns, permitindo atender mais rapidamente uma movimentação de carga muito maior.

A origem já defi nida ou não, o sucesso portuário alcançado ou perdido, fi cam patentea-dos em muitos e diferentes lugares. Petersburgo fundada e alçada a capital das Rússias; Veneza, hoje com seu Arsenal museifi cado e o grande comércio extinto; Dubrovnik; Cadiz sucessora de Sevilha. Porto resgatada por Leixões; Ma-puto, que se aterra, expande, providencia um cais-ponte.

Os grandes cargueiros atuais são verda-deiros porta-contêineres, recipientes metáli-cos modulados para o transporte a granel, de objetos, bens perecíveis. Refrigerados ou não, constituem módulos tridimensionais para se ju-staporem em porões ou cobertas, cada vez mais nas cobertas. Volumes que prometem resistir

14

também e de forma diferenciada em alguns elos do antigo ultramar lusitano: as docas de Lisboa; atabalhoadas expansões em Santos; novos reptos para a capital moçam-bicana; os sonhos, propostas e adequações de Macau.

Os novos cruzeiros para turistas, não somente por suas alentadas proporções, como pelo seu programa e desenho são in-éditos, exclusivos para passeio. Seu castelo toma praticamente todo o convés, lemb-rando grandes edifícios de apartamento; sua motivação é o lazer a bordo, no qual as escalas são meros complementos para visitação e divertimento.

Esses verdadeiros resorts fl utuantes respondem a um programa de arquitetura náutica, que não existia antes e extrema-mente especializado. O que interessa aqui é o seu impacto urbano desprezível, quase nulo, contraposto àquele dos porta-con-têineres. Desde as grandes navegações se mesclavam, na verdade, as preciosas car-gas, raros passageiros, além das próprias armas defensivas e outros apetrechos.

No mundo industrial, viajantes mais numerosos puderam compartilhar com o carregamento crescente as travessias mais rápidas e seguras a vapor. Lá vai uma centúria em que os passageiros vieram a preponderar no castelo, correspondente-mente ampliado. Tais “vapores”, então, pas-saram a ser conhecidos signifi cativamente como “transatlânticos”. Termo hoje dupla-mente anacrônico.

Para receber estes navios também para muitos passageiros, as aglomerações urbanas mais alentadas providenciaram equipamentos condignos, como terminais apropriados, alfândegas específi cas, esta-ções de embarque. Para milhões de imi-

à maresia, ao empilhamento, aos choques de seu trasladar.

Momentos críticos, o embarque e o desembarque por milhares de anos foram feitos por simples transbordo de embarca-ções menores ou diretamente para a praia. Com a expansão comercial contemporânea e o crescimento do número, porte e peso das mercadorias, com o advento dos guin-dastes móveis mais resistentes, dos trapi-ches e dos pontões, suavizou-se o brutal trabalho na estiva. Logo os cais far-se-ão incontornáveis.

A fotografi a se junta às crônicas para o registro do congestionado e maior porto do mundo que foi então Londres, da ad-equação progressiva de Hamburgo sobre o Elba, de Marselha. O estaqueamento, o enrocamento, os aterros a se prolongarem e a facilitarem a carga e descarga dos porões de navios, em meio a muita azáfama, por toda parte, em cada continente.

Hoje, a carga e descarga se valem de verdadeiros pórticos e pontes rolan-tes, como na indústria pesada. O manejo daqueles contêineres redesenha a orla e im-põe, além do grande calado, imensas áreas de depósito e para acesso a diferentes meios de transporte terrestres. Desafi a, com as plataformas, ofi cinas e leitos ferroviários, com as alças, os trevos e os estaciona-mentos rodoviários, a própria conformação citadina existente.

Ou as cidades portuárias se adaptam, reformam por meio da oferta de nova borda de águas mais profundas e terrenos mais es-paçosos, ou perdem o interesse e a oportuni-dade para algum sítio vizinho mais vantajoso, ou mesmo algum estabelecimento distante. Já não se trata somente do que dita o calado, porém do que desencadeia a intensa espe-cialização do transporte cargueiro, açodada pelos caixotões estandartizados.

A busca de um sítio mais atento a tais necessidades recentes se deu gritan-temente em Seattle, Nova York e Buenos Aires com instigantes revitalizações de seus antigos piers, terminais e armazéns. Como

15

BIBLIOGRAFIA

CABAÇO, José Luis. Moçambique: identidades, colonialismo e libertação. Maputo, Marimbique, 2010. 358p.

CASTRO, Josué de. A cidade de Recife: ensaio de geografi a urbana. Rio de Janeiro, Casa do Estudante, 1954.

CORTESÃO, Jaime. O império português no Oriente. Lisboa. Portugalia, 1968. 343 p. (Obras completas, 15)

CASTELLS, Manuel. The informational city. Oxford/Cabridge, Blackwell, 1989. 402 p.

KOSTOF, Spiro. The city shaped: urban patterns and meanings through history. London,Thames and Hudson, 1991. 352 p. .The city assembled: the elements of urban form through history. London, Thames and Hudson, 1992. 320 p.

MARX, Murillo. “Das tulhas, pelos trilhos, aos trapiches”. In: FRIDMAN, Fania e ABREU, Maurício. Cidades latinoamericanas: um debate sobre a formação de núcleos urbanos. Rio de Janeiro, Casa da Palavra, 2010. 183 p., 167-179 p.

MENÉRES, António. Crônicas contra o esquecimento. Matosinhos, Edium, 2006. 237 p.

MORAIS, João Sousa. Maputo, património de estrutura e forma urbana. Lisboa, Horizonte, 2001. 247 p.

MINDELO, património urbano e arquitectónico. Lisboa, Ciaud, 2010. 191 p.

SANTOS, Milton. O centro da cidade do Salvador: estudo de geografi a urbana. Salvador, Progresso, 1959. 196 p.

grantes formou-se o complexo de triagem, quarentena e encaminhamento novaiorqui-no de Staten Island; para poucos ilustres visitantes se adornou o tardio Embankment londrino e se ergueu o maior monumento em Mumbay. E tantos mais mundo afora, descendentes da Piazzeta veneziana.

Transatlântico se tornou termo ana-crônico pela nova ordem geopolítica em que o Atlântico deixou de ser o único oceano muito singrado, bem como em decorrência de os turistas eventuais agora não terem destino e motivação, que não seja a recreação. O nome “transoceânico” seria cabível, porém já ridículo à vista da velocidade dos grandes jatos atuais.

Os usuários daqueles “cruzeiros”, que podem acostar como em Lisboa e Rio de Janeiro, utilizam-nos também como hotéis para pernoite quando têm de atra-car ao largo. Em ambos os casos, esses turistas peculiares abandonam seu resort, bastando-lhes um acesso em terra mínimo e condizente. A relação será outra com a urbe, dispensadas maiores intervenções, em volume e área, para seus contínuos embarques e desembarques.

Estas rápidas notas destacam algu-mas mudanças na relação porto/cidade. Detectam a milenar imposição do calado e a crescente infl uência da especialização no transporte de cargas e de passageiros. Se o calado foi decisivo para a origem e o sucesso dos estabelecimentos portuários, determinando seu sítio geográfi co, a espe-cialização dos navios atuais afeta também o tecido urbano. Um cais, um terminal, seu portão desde a revolução industrial; hoje, os invólucros padronizados de mercadoria cobram muita área e melhoria e o novo turista sem rumo, quase nada.

16

There are 48 old houses lining up along the Pátio da Claridade. They are two-storey gray brick buildings. The roofs are laid with tiles sup-ported by timber joists resting on the load-bearing walls. However, the houses bear different features as they were built at different times. The size of the land for each house is more or less 45 sqm. The building occupies nearly the whole piece of land, whiles only a small courtyard (air-well) remains at the rear part. The kitchen is beside the courtyard for better ventilation.

It can be said that the above features make up a basic module for the 48 old houses. The houses with the entrance open to Pátio da Claridade, except the houses no.10 and no.12, are the simplest exam-

Jay Ho Pui Kei*

Nuno Soares (Photography)*

HERITAGE XXARCHITECTURE

Pátio da Claridade

17

HERITAGE XXARCHITECTURE

ple of such kind of module, though they vary in height, width, details of the openings and the cornice. Their elevations are simple with simple form of cornice and few of the windows have the pediment in straight line form. A short parapet is added on the top end of the front wall. This kind of short parapet is infl uenced by the European architecture which is different from the traditional Chinese architecture.

Among the houses on Pátio da Claridade, the houses no.10 and no.12 are outstanding. In fact, these two houses are adjacent to each other, forming one big house which is taller and wider than its neigh-bours. This structure has the following features:

• Several courses of granite stones are set on the foot of brick walls. It can provide a better damp-proof to the brick walls.

• On the front elevation, the openings of its ground fl oor are encased with granite jams and lintels. The original doors are retained. The door panels are made of solid wood without any penetrating part. They are painted in red and opened with a wooden shaft. A big cast iron shutter with a solid bar of 1-inch diameter is used. The existing windows are in metal frame with glass panels. The original materials used cannot be traced now.

• The openings of the upper fl oor on the front elevation are four windows with ornaments of triangular pediments. The pediment above the window at the right corner is missing. There have been changes to all these four windows. The openings of the windows extend down to

18

the fl oor and hence the windows are divided into two parts. A bal-ustrade is set inside the lower part that can still be seen in one of the windows, while the outer one might be timber louvers originally. For the upper part, glass window in wooden frame is usually set behind the timber louvers. The design of the window benefi ts to the indoor environment: in winter it can provide daylight but stop the cold wind, vice versa in summer it allows the gentle breeze to ventilate the indoor but keeps out the heat of the sun. A relevant original form of such type of the window still can be seen in Macao elsewhere (e.g. the house no.4 of Barra Street, dated back to 1898).

• There are fi ve ventilation holes close to the eave on the front elevation. The holes are 200 milimetres in diameter. They give the ventilation to the area between the false ceiling and the roof.

• The roof is of the style of fl ush gable roof but there is a narrow eave at both sides of the lateral walls. It gives an illustration as if it were a four-pitch roof or a gable and hip roof.

All the above features give this house a better quality than the oth-ers in the street.

The 21 shop-houses on Travessa da Assunção are divided into two rows by a small square. They were not built in the same time though they look alike that all have the balconies. The balconies are united in form and materials: reinforced concrete has been used to their slabs, the fences of the balconies are also made of concrete with steel bars inside. The openings of the upper fl oor are more or less the same in style. Two timber doors with penetrations open to the balcony. However, the row of buildings in the northwest of the small square was built before the row in the southeast. The latter, i.e. a total of 10 houses numbering from 2A to 2M, were probably built in the 1930s while the reinforce concrete started to be applied in Macao. So, their balconies were built simultaneously. The former, i.e. a total of 11 houses, numbering from 2 to 22, were built in the early 1920s or even earlier. Their balconies were added later, when the other row of houses were being constructed. We can fi nd the proof from the structure. The houses built earlier use timber lintels with a section of about 260 mm (W) by 200 mm (H) for the opening of ground fl oor to bear the loading of the above break wall. It is obvious that steel bars are embedded in the brick walls upon the timber lintels to strengthen the structure. They are so weak in structure that they are in the bad conditions and that some of them have acquired the temporary support. The open-ings of the original windows of the fi rst fl oor were enlarged to make the doorway to the newly added balconies.

Because Travessa da Assunção connects the Praia do Manduco Street and Almirante Sérgio Street and is wider enough to let the car goes through, the ground fl oor of the houses use for business is so common whiles the upper fl oor keeps as residential. Some of the houses maintain the traditional timber doors of the ground fl oor. The opening is closed by 3 pairs of doors of solid wooden panels that can

19

be taken away easily for the convenience of doing business. Most part of the exterior wall of these 48 houses is plastered and

painted. There is an exception that the wall on the front elevation of the houses no.2A to no.2M of Travessa da Assunção is covered with Shanghai plaster. In Macao, people started using Shanghai plaster in 1930s. In this case, it seemed that the builder tried to distinguish these newly built houses from the others.

The 4 shop-houses in Almirante Sérgio Street have arch form ‘qilou’ in their front. The arches show the shop-houses were built earlier than those shop-houses with ‘qilou’ supported by a rigid hori-zontal concrete beam built in 1920s or after. The arch was substitut-ed by the concrete beam because the latter was more convenient to achieve a big span for the shop front. There were many shop-houses with arch form ‘qilou’ in Macao. It is pity that only few of them re-mained in Macao now. These four shop-houses in Almirante Sérgio Street become so signifi cant that they compose the biggest cluster remain in Macao.

The colonnade is about 2 metre wide. The span of the arch is 3.4 metre, with a height of 3 metre. Each arch marks an individual shop-house unit. The upper part of the columns and the arch are made of brick while the base and the lower part of the columns are made of granite stones. The openings in the front part of the ground fl oor are about 3.2 metre wide and 2.8 metre high. A timber lintel is supported by granite door jams. A detail remained in the no.219 is worth to be noticed. There are holes lining up on both the lintel and the door jam. They were originally for putting logs vertically as a fence. A few years ago, we could still see an example with such type of shop front used in a traditional Chinese wine workshop (no.46A, Rebeira do Patane Street). It was pity that the wine shop could not escape from being demolished. Now we can only see some examples used in residential buildings, e.g. the Mandarin House.

Among the 48 houses around Pátio da Claridade, there are several different types of house which are typical in Macao:

1. The house on.10 – 12 Pátio da Claridade, whose ground fl oor was originally designed for storage.

2. The houses on Pátio da Claridade except no.10-12, which are the popular 2-storey brick houses without any verandah or balcony.

3. The four shop-houses with the arch form ‘qilou’ on Almirante Sérgio Street. They are the earlier type of shop-houses with ‘qilou’ in Macao.

4. The shop-houses on Travessa de Assunção have re-inforced concrete balconies. The houses no.2 to no.22 are the vivid example that show how people add balconies to their houses for upgrading.

Therefore, the diversity of houses in Pátio da Claridade demon-strates the progress of the development of houses in Macao, which is worthy of preservation. * Architect

20

As Torres de KaipingArq. Cristina Veríssimo com Joy Tin Tin

HERITAGE

21

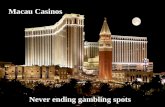

As Torres de Vigia de Kaiping também chamadas de “Diaolou” localizam-se numa paisagem rural e plana, na maior parte campos agrícolas, no Delta do Rio das Pérolas na Província de Guangdong.

Jiangmen, Xinhuei, Kaiping, Taishan e Heshan são os principais distritos da província de GuangDong onde podemos encontrar este tipo de Torres. No entanto é em Kaiping onde se localizam o maior numero de Torres e as mais importantes.

Estes edifícios fortaleza foram construídos durante os anos de declínio da Dinastia Qing (1644-1911) e o inicio da nova república (1911-1948), por emigrantes chineses para habitação e protecção aos constantes saques e pilhagens comuns naquela época.

HERITAGE

A emigração estava limitada aos homens em idade activa. Por isso muitos emigrantes regressavam, para junto das suas famílias ou para constituírem família e compravam terras. Muitos só regressavam defi nitivamente no fi m da vida para serem enterrados em solo da Pátria Mãe, mas construíam casa que visitavam pelo menos uma vez por ano .

Estes emigrantes traziam com eles a infl uência de diferentes estilos arquitectónicos de locais por onde tinham passado. Sobretudo entendiam importante, evidenciar e representar a diferença, de toda uma experiência tida noutras culturas e com isso mostrar que eram diferentes e sobretudo ricos, já que podiam gastar enormes quantias na construção das suas casas.

Através de postais eram transmitidas as

22

ideias dos promotores, que eram registados em desenhos, para serem posteriormente construídos por construtores locais. Grande parte destes projectos eram feitos em Macau e Hong-Kong, por técnicos que interpretavam, adaptavam e infl uenciavam as vontades do cliente. Daí que fosse natural uma forte infl uência a estereótipos arquitectónicos europeus, resultado da infl uência colonial Portuguesa e Inglesa: arcos abobadados, torres italianas e até muçulmana: os minaretes.

Por razões de protecção, somente os últimos pisos eram usados para representar sua riqueza e infl uência. Os pisos baixos têm poucas aberturas, mostrando sua característica defensiva, à semelhança das Torres de Prestamistas espalhadas também por estes distritos de GuangDong. As Torres de Kaiping foram construídas posteriormente, pelo que em meu entender a sua morfologia

HERITAGE

23

arquitectónica tem uma infl uencia directa das Torres de Prestamistas, alterando no entanto a sua função e localizam-se sobretudo em meio rural.

Apesar da variedade de formas, estas Torres partilham algumas características tais como: paredes grossas, portas feitas de ferro, pequenas janelas tipo “gateiras”, permitindo disparar escondidos em cada lado das paredes.

As torres com paredes grossas e poucas aberturas para além de serem um bom posto de vigia e defesa, podiam ainda suportar desastres naturais tais como inundações e tufões. O interior era muito semelhante a nível tipológico: escada central ligando todos os pisos, permitindo boa ventilação vertical e evitando corredores nos pisos. No primeiro piso localizava-se a sala de estar. Os pisos do meio destinados a quartos e os últimos pisos aos espaços de comuns e de permanência

da casa, que coincidiam com os pisos onde a fachada era mais “exuberante”. Todas as casas tinham um espaço de destaque, onde se localizava um altar de homenagem aos antepassados.

Cerca e 1920 as Torres começaram a ser construídas em betão. Esta nova tecnologia permitiu Torres mais altas, elegantes e sobretudo mais rápidas de construir. A tecnologia e materiais eram importados directamente de Macau e Hong-Kong. Também eram usados no interior materiais de revestimento, elementos decorativos e até mobiliário com forte infl uencia estrangeira. Estes últimos pisos tinham ainda a função de vigia e era comum contratar exércitos privados que defendiam as casas e as terras.

Entre 1920 e 1930 no auge da sua construção, foram registados mais de 70 casos de assaltos perigosos só em Kaiping. Uma noite, em Dezembro de 1922, um

grupo de bandidos raptou o director e 17 estudantes da escola Secundária de Kaiping. As tropas de uma das famílias poderosas da zona, conseguiram descobri-los com a ajuda das luzes de uma das torres Diaolou na aldeia Yingcun. Este incidente causou muita preocupação e muitos emigrantes construíram mais torres .

As Torres de Kaiping dividem-se em três grupos: as “denglou” (Vigia nocturna), “zhonglou” Torres comunais e “zhulou” Torres de habitação. Seguem-se alguns exemplos que ilustram os diferentes grupos.

“DENGLOU” TORRES DE VIGIA - As torres de vigia eram construídas para defesa de várias aldeias. Eram geralmente localizadas à entrada das aldeias, ou em elevações junto ao rio, funcionavam para dar o alarme. Eram construídas com dinheiros dos próprios aldeões, tinham homens contratados que viviam na Torre e em caso de ataques,

HERITAGE

24

HERITAGE

25

implantação superior aos restantes tipos de Diaolou, de modo a poder albergar todos os aldeões em caso de ataque. São também mais baixas tendo entre dois e três pisos. Um exemplo disso são as torres construídas pelos Hakka people .

Em caso de inundação a população abrigava-se também nestas torres e permaneciam aí até a água baixar. Daí que para além deste aspecto muito sólido tinham boas condições de ventilação.

São as torres mais antigas, à semelhança das torres de prestamistas localizam-se num ambiente urbano. A “zhonglou” “Yinglong Lou” mais antiga localiza-se em San Men Li, a 15 minutos a oeste da cidade de Kaiping. É uma torre com três pisos construída em tijolo maciço, servindo de refugio a inundações. Os dois primeiros pisos com aspecto mais robusto foram construídos entre 1436 e 1449 e o ultimo piso foi adicionado em 1919. As paredes têm mais de 90 cm de espessura e tem uma torre de vigia em cada canto. Nas inundações de 1884 e 1908, os aldeões refugiaram-se no último piso e sobreviveram, por isso ainda hoje continuam a preservar este edifício.

AS “ZHULOU” TORRES DE HABITAÇÃO - As zhulou são construídas no campo e eram a epítome da função dupla das diaolou. Eram construções altas e espaçosas, com requintados detalhes esculpidos, ofereciam dependências confortáveis e elegantes. Por razões de protecção somente os últimos pisos eram usados para representar a riqueza e infl uência dos donos. Os pisos baixos têm poucas aberturas, mostrando sua característica defensiva. Eram um repositório de ideias e tendências trazidas pelos chineses emigrados. Isto também se refl ecte na variedade de infl uências que se podem observar nos estilos arquitectónicos adoptados, incluindo a característica interessante dos pormenores ocidentais reproduzidos nos andares superiores: colunatas, terraços, balaustradas, castelos. O exterior da torre refl ectia o poder económico do seu dono e assimilação da

HERITAGE

as torres funcionavam em conjunto lançando avisos e formando grupos de homens que combatiam os piratas. Tratando-se de um território bastante plano e junto ao Delta do Rio das Pérolas, existem imensos canais usados pelos piratas para surpreender e atacar a população. São na maior parte construídas totalmente em betão, têm entre cinco e sete pisos e pouca área de implantação, o que as torna bastante esbeltas.

Denglou Fangshi: localiza-se a norte da aldeia Tangkou a 11 km a este de Kaiping e tem uma localização de controle do território.

Também chamada “Farol”, tem cinco andares com uma altura de19 m e é feita em betão armado. Abaixo do terceiro piso estavam localizados os quartos de quem estava de vigia. O quarto piso era amplo e no quinto piso localizava-se o posto de vigia num estilo ocidental com abobadas. Era equipada com um gerador, luzes de vigia e armas, à semelhança de outras torres de vigia. Era ainda o ponto de protecção para as aldeias vizinhas em caso de ataque de bandidos. O seu nome deriva do facto de ter existido um grande foco instalado no seu topo, semelhante ao de um farol. Esta torre é ainda vista das aldeias vizinhas. O edifício está protegido.

Bianchouzhu Lou (Diaolou Inclinada)- Construída em 1903, tem sete andares. Levou dois anos a construir, devido a difi culdades de fi nanciamento. Quando a construção atingiu o terceiro andar, a casa já se inclinava cerca de 10 centímetros para sudeste e, hoje, o seu eixo central tem uma inclinação de mais de 2 metros.

É de notar que o betão era um material pouco usado na altura, implicando uma nova tecnologia de construção, que neste caso não estava totalmente dominada.

AS “ZHONGLOU” TORRES COMUNAIS - eram estruturas sólidas e simples construídas perto de uma aldeia, para proporcionar uma defesa comunal. Os aldeãos contribuíam colectivamente com dinheiro para a sua construção e cada família tinha direito a uma divisão. Têm normalmente uma área de

26

cultura ocidental considerada mais avançada.Diaolou Ruishi - talvez a mais magnifi ca

diaolou de todas, construída por um homem que geria um banco e uma farmácia de medicina chinesa em Hong-Kong. A diaolou Ruishi e tem uma área de 92 metros quadrados. Foi construída em 1921 quando as diaolou começaram a popularizar-se. Tem nove andares, sendo a mais alta diaolou em Kaiping. Demorou três anos a construir usando mão de obra local mas com materiais importados, domina a aldeia. Cada andar tem janelas quadradas em alinhamento com os três andares superiores, constituídos por pavilhões e corredores sinuosos. Localiza-se na vila de Jinjiangli, na Municipalidade de Lianggang.

Os cantos decorados e com janelas do cimo até ao piso mais baixo, com uma galeria em consola percorrendo os quatro cantos, com abobadas nos cantos e com um pavilhão octogonal de dois pisos no topo Junto às torres construíam-se lagos de lótus. Estas Torres de uma forma geral tinham uma forte relação com a natureza. A sua elegância face à paisagem e a criação de espaços exteriores de lazer e contemplação era comum.

Claramente em competição com a torre vizinha Shengfeng Lou, também terminada no mesmo ano, mas por um emigrante dos EUA, tem uma colunata, abrangendo dois pisos em consola. Entre as duas torres existe uma torre de vigia construída pelos aldeões em 1918.

Located in Xiabian village, Baihe township, the tower was built it in the 1920s. It has 3 stories of the key beds and 2 stories of pavilion on the top, The front part on the 4th story is the colonnade, there is a swallow nest (the popular way to describe the salient part of Kaiping Diaolou with shooting holes) in each corner, The style of the top fl oor is the European castle style. It is a typical lime-sand Clay towers.

Diaulou Shilu - Localiza-se no pequeno jardim do mercado em Xiabian Cun a sudeste de Kaiping, e foi construída em 1924. Tem três pisos e mais dois pisos de pavilhão um deles com uma colunata. Tem quatro

HERITAGE

27

torreões de defesa do ultimo piso. Visto o cimento ser quase desconhecido na China, foi importado de Hong-Kong a custos muito elevados. Apesar do dono original ter vivido no Peru e em Singapura, só conseguiu pagar uma construção em taipa (mistura de argila, açúcar, algas e goma de arroz). O solo em argila vermelha deixou uma coloração de cor alaranjada, nas paredes e a sua extracção criou um pequeno lago junto à torre. O que o cimento permitiu pagar foi reservado para os últimos pisos com torreões parecidos com pimenteiros e gateiras em forma de T-invertido e um pavilhão abobadado.

Tang Ko - Os donos mais ricos construíam conjuntos de torres, um exemplo disso é o conjunto Tang Ko. Este conjunto formado por sete torres, que se dispunham ortogonalmente ao longo numa alameda. Cada esposa vivia numa torre, que se distinguiam de acordo com as suas necessidades e gostos Também existi uma torre para viveres, serviçais e exercito pessoal.

Este conjunto foi feito por um arquitecto americano que veio durante meses estudar o local. Percebe-se aqui uma vontade de cruzar estilo arquitectónicos, em que cada torre tem um estilo individualizado, sem no entanto e perder a ideia de conjunto. Este conjunto rodeado de campos agrícolas, mas está perfeitamente delimitado através de um portão e de lagos artifi ciais.

Os jardins combinam ainda um gosto

europeu, com a sabedoria chinesa de incorporar lagos. De referir um soberbo pavilhão, todo feito em estrutura metálica e um pelourinho, que têm uma localização destacada no desenho do jardim.

A Torre mais erudita, pertencia ao patriarca da família. As fachadas tentam combinar claramente dois estilos, o Europeu e o Chinês, mas de uma forma harmoniosa e erudita.

Tem janelas e varandas a partir do segundo piso, muito ao estilo Neoclassico, perdendo um pouco o aspecto maciço comum nas outras torres.

O interior, é bastante requintado usando alguns materiais importados e o chamado “shanghai plaster” muito comum em Hong Kong e Macau. A escada localiza-se ao centro e tal como nos outros exemplos existe um piso para velar pelos antepassados. O interior ainda tem algum mobiliário existente.

Grupo de Diaolou na vila de Zili - A maior colecção de diaolou é em Zili Cun. O grupo está espalhado por três aldeias (Anhe li, He’an li e Yong’an li), a 12 Km a este de Kaiping e é constituído por quinze casas bem preservadas e lagos . As 15 torres têm na maioria quarto pesos de altura, são feitas de betão, mas o ultimo piso tem uma série de arcos e balaustradas e torreões de vigia. A mais antiga, a Longsheng foi construída em 1919 e mais recente a Zhanlu foi construída em 1948. A diaolou Mingshi (1925), é um

excelente exemplo de diaolou e localiza-se nas traseiras da vila. Com sete pisos, tem ainda toda a mobília dos fi nais da dinastia Qin e utensílios originais no seu interior. No primeiro piso localiza-se a sal de estar e nos pisos intermédios os quartos. O quinto piso está destinado ao altar onde os membros da família prestam homenagem aos seus antepassados. É neste piso que se localiza a colunata e os torreões. Existe um pequeno pavilhão hexagonal com uma mistura de infl uências europeias e chinesas no sexto piso. Existem projectos para transformá-la num museu. Os donos continuam emigrados.

Um estudo recente indicou que das cerca de 3000 torres que foram construídas em Kaiping e em outras cidades da província de Guangdong, apenas existem cerca de 1833 torres sendo que a maioria pertencia a proprietários tinham emigrado ou a descendentes. Grande parte delas são em betão armado. As mais antigas em tijolo foram demolidas, já que o tijolo pode ser reciclado ao contrario do betão. Também no inicio da nova republica, o partido comunista antipatizava com estruturas construídas com aspecto militar, por isso asseguraram que muitas torres tivessem sido demolidas.

Estas torres de vigia constituem um exemplo arquitectónico e cultural singular do cruzamento do ocidente e oriente. O Diaolou foi proposto para classifi cação do património mundial da UNESCO.

28

Planning:Discourse and praxisEliezer Bandonill Villaruz*UAP / AAM

PROFESSION

29

Planning is an inherently moral practice – a praxis (practical application) – in the sense that it affects the way we live – the rela-tions among people and their institutions.

There are three streams of Planning as practiced and often discussed by many planners, (1) it is a moral discourse, the central and core stream which is con-cerned with ethical choice or answering issues on how people live with one an-other, (2) a technical discourse, this is how effectively and effi ciently relate the means to ends, and (3) Utopian discourse, which is concerned with visionary images of “good life.”

In Planning, these three separate streams of discourse must be brought together and woven in such a way to meet public interest and community goals. That is the special virtue of the praxis of planning.

But we need also to understand that such goals intended majorly for stakehold-ers are met through proper execution of the planning practice, for example, public discussions should be the forefront activity in re-assessing and validating community goals and public interest, and such, the community or its legitimate representatives will ratify these goals after serious discus-sions and deliberations, without this, any of the streams as discussed is in no way be of benefi t.

Now, What do we expect from Plan-ners?

The role of planners should be bound specifi cally with willed or intended social change, but which should also morally defensible or “good.”

Possessing such skills and knowledge for effective planning is essential, that means the planner know or ought to know, (a) to facilitate the process “negotiation” so that people can resolve their differ-ences and move forward, (b) able to defi ne problems that have risen to the surface of public discussion and concern in ways that makes them tractable, (c) effi cacy of the intervention strategies potentially

* Part reference / source: Jay M. Stein (1995) Classic Readings in Urban Planning. ** Majority of terms, text, statement on this article are from a collective view of the subject by the author Eliezer Villaruz.

*Architect

PROFESSION

available, (e) political dynamics that bear on a solution of the problem, (f) how to get new pertinent knowledge and proposed intervention strategies, and (g) policies and images of the “good” society and whether this can achieve “Utopian” visions.

Furthermore, the planner should also be resilient, this is one important virtue, as there will always be obstructions, for example, since planning goal is said to be with the common interests of society’s members, there are always politicians who ignores consistency or prevents grand schemes to placate interest groups. These should be anticipated, and a strat-egy should be applied for to re-establish and keep goals on track on the planning process.

Since the process involves com-plex integration of strategies effected through amounted research, discussion and negotiation, the planner also acts as the facilitator of the continuing program of deriving, organizing and presenting a plan that promotes the common good and preserving the rights and interests of the public.

All of these in regard to the discourse and praxis of planning should be taken into consideration for all issues pertain-ing to either urban, rural, developmental and comprehensive planning, keeping in mind that such efforts to establish policies and strategies should be placed in proper implementation and handling by compe-tent professionals knowledgeable to the process.

In conclusion, what is truly left for the practice and the planner is to learn from experiences of the past and to re-assess and evaluate current problems of today and plan….plan, plan for its resolution towards the future .

30

31

Debaixo do vasto horizonte brasileiro, o olhar não tem onde se fi xar. Na paisagem, a extensão está sempre ímplicita e a arquitectura é pri-mordial. A arquitetura brasileira procura sempre um lugar simultâneo para o indivíduo e para o colectivo, um lugar simbólico que bem como a linguagem é feito de singela dignidade estética.

A extraordinária obra de Oscar Niemeyer, percorre mais de sete décadas e centenas de notáveis peças e ícones urbanos. Seus edifí-cios não apenas se estabelecem no decorrer do tempo com sereni-dade, como parecem ir puxando a si a razão abrangente dos tempos.

Uma ideia de Deus e LiberdadeRui Leão*

:

32

Abertura da exposição Oscar Niemeyer: A Geometria da Liberdade, Museu de Arte de Macau, 24 de Marco a 8 de Maio 2011

Opening of the exhibition Oscar Niemeyer: The Geometry of Freedom, Macau Art Museum, 24th March to 8th May 2011

33

Apartir das obras de Pampulha e de Brasília iniciadas na década de 40 (séc.XX), o mestre brasileiro deu corpo à Arquitetura Brasileira, fê-la mais livre e aberta. Não que ela não existisse já, mas nunca ela se tinha traçado com tanta consciência e propriedade cultural. Apartir de Pampulha e de Brasília, a obra de Niemeyer apresenta-se como via alternativa à arquitectura funcionalista que com sua retórica dominava a produção da arquitectura de autor por todo o lado, velando à arquite-tura o desejo do específi co, do local e do amado sítio em todas as suas dimenções metafísicas e concretas.

A arquitetura é uma síntese do mundo, uma totalidade interior que espelha a totalidade infi nita e incomensurável do real. Essa síntese, na arquitetura de Oscar Niemeyer é redonda e joga-nos para a vida com maior encanto. A arquitetura de Niemeyer incita a descoberta da simplicidade da beleza: a beleza natural e urbana do seu Rio de Janeiro, a beleza nas curvas da mulher amada, do puro prazer de viver: como dizia Ferreira Gullar, Oscar nos ensina que a beleza é leve e que o sonho é popular.

O Oscar Niemeyer gosta de dizer que como o André Malraux, ele tem um museu particular onde guarda tudo o que ele viu e amou na vida.

Seus edifícios estão carregados de uma criatividade que combina a simplicidade—na resolução do programa, na compreeção do sitio, na solução estrutural, na escolha formal—com o domínio da forma livre, da curva conspurcada de segmentos de recta e de uma relação sempre inesperada e mental do objecto com seu enquadramento natural; e de suas sínteses resultam objectos e espaços cujo movimento e percep-ção despertam em nós o puro prazer da beleza.

Bem como suas palavras, sua arquitectura é um constante mani-festo. Afi rma o desejo de conquistar uma relação directa e primordial entre o corpo e o espaço, relação feita apartir de riscos desenhados com a mão e guiados com carinho por uma ideia em que o desejo é o verdadeiro deus do homem, e a razão vem-no seguindo, hu-milde e fascinada: O congresso Nacional e a Praça dos Tres Poderes com a ideia democrática de que se pode percorrer o edifício em toda a sua extenção; a colunata da sede Mondadori, onde os pilares são tão impor-tantes quanto o espaço entre eles. Todos os seus projectos falam assim.

Os seus edifícios descrevem-se como um poema aberto, compreen-sível por todos: a Catedral de Brasília é feita de 16 pórticos que pousan-do num círculo no chão se encostam e seguram no cume; o Museu de Niterói se eleva do chão num apoio central para permitir que a paisagem não seja interrompida por ele; o alpendre, de Ibirapuera recorta uma nu-vem de sombra que liga todos os edifícios do conjunto, permitindo que a natureza do Parque fl oresça entre a arquitetura e as pessoas... A graça e elegância das suas obras são fruto de um desejo de inventar o mundo de novo a cada projeto, de querer surprender quem vê e entra no projeto. De desenhar o desejo com a vontade que esse desejo se projecte naquele que vai usar o espaço; que o espaço e a forma sejam apreen-didos por esse lado mais natural e humano que há em nós, antes de sermos tomados pela nossa consciência e julgamento. É aí, ao dentro de nós que a arquitetura do Niemeyer nos leva: a um sítio onde estamos livres da consciência de nós. É aí que a sua arquitetura nos deixa fi car e é aí que ela é profundamente Brasileira e humana. *Arquiteto

Comissário da Exposição

34

the structural solution, the election of the forms – with a predominance in the freedom of forms, the curves sullied by line segments and a con-stant unexpected and mental bond between the object and its natural environment; thus resulting in objects and spaces whose motion and perception stimulate the pleasure of beauty within us.

Just like his words, his architecture is a constant manifest. It estab-lishes the desire to gain a direct and primary connection between body and space, achieved by hand drawn lines carefully guided by an idea that desire is man’s real god, followed by reason, humble and fascinat-ed: The National Congress and the Three Powers Plaza with the pos-sibility of walking through the building in all its extension; the columns of the Mondadori headquarters, where the pillars are as important as the space between them. All his projects express themselves this way.

His buildings are described as an open poem, understood by all: the Brasilia Cathedral is made of 16 columns that land in a circle on the ground and lean towards the summit as its support; the Niteroi Museum rises from the fl oor in a central support to enable an uninterrupted view of the landscape; the Ibirapuera canopy delineates a shadow serving as a bond to all the buildings in the complex, allowing nature in the Park to fl ourish between architecture and people ... The grace and elegance of his works are the result of a desire to invent a new world for each proj-ect, aiming to surprise those who look and enter. Drawing desire with the will that this desire is refl ected on those using the space; that space and forms are captured by the most natural and human side within us before we are overtaken by our conscious and judgment. This is where Niemeyer’s architecture aims to lead, within us: a place where we are free from our consciousness. This is where his architecture leaves us and this is where it is profoundly Brazilian and human.

The eye has no fi xing point under the immense Brazilian horizon. Ex-tension is always implied in the landscape and architecture is essen-tial. Brazilian architecture simultaneously seeks a combination of the individuality and the combined, a symbolic place that like language is made of a simple aesthetic dignity.

The extraordinary work of Oscar Niemeyer covers more than seven decades and hundreds of remarkable pieces and urban icons. His buildings are not just serenely nestled over time; they seem to contain a comprehensive reason of their times. Starting from the works of Pam-pulha and Brasilia in the 1940s, the Brazilian master gave essence to Brazilian architecture, providing it with freedom and openness. It was not like it did not already exist, but it had never been expressed with such consciousness and cultural awareness. As from Pampulha and Brasilia, Niemeyer’s work presents itself as an alternative to functionalist architecture that was rhetorically present everywhere, concealing its pur-pose, place and dearly loved location in all its metaphysical and genuine dimensions.

Architecture is a synthesis of the world, an interior wholeness that refl ects the immeasurable and infi nite completeness of reality. In Oscar Niemeyer’s architecture, this synthesis is round and throws us into life with more enchantment. Niemeyer’s architecture incites us to discover simplicity and beauty: the natural and urban beauty of his Rio de Ja-neiro, the beauty of the beloved woman’s curves, the sheer pleasure of life: as Ferreira Gullar said, Oscar teaches us that beauty is simple and dream is popular.

Oscar Niemeyer likes to say that as André Malraux, he has a pri-vate museum where he keeps everything he saw and loved in life.

His buildings are loaded with a creativity that combines simplicity – in the resolution of the project, the understanding of the environment,

An idea of God and Freedom

*ArchitectExhibition Commissioner

Rui Leão*

35

September 15, 22 and 29, 2010

Speculations, casesand seminal discussion on architectural practice for the cultural sector

Prof. Alvin Yip, RICE Lab, School of Design, PolyU, Hong Kong

The course begins with the mutation of architectural practice. From the eras of craft, construction to creative industry, the architect reacts to his time in both theorization and fi elds of practice. The Biennale for Architecture, for instance, is a new and signifi cant frontier emerging from globalism and the information boom.Today, cultural architecture exists in a dichotomy of practices- one concerning its empowerment through community engagement, one could argue as a form of democracy, while the other pole under our revamped cultural authorities- building commission is deployed now as a strategic tool cut across institutional, city and diplomacy levels.

For the new accreditation of the local profes-sionals being soon applied in Macau, AAM has organized a series of seminars for the continu-ous professional developing since second half of 2010. Scholars and experts from various districts were invited to give lectures to AAM’s members and the interests. In September 2010, Mr. Alvin Yip, assistant professor at the School of Design, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, gave 3 lectures in AAM, with the topic “Architecture as Cultural Practice?” On November 7, Dr. Guo Xiangmin, vice direc-tor of CULD at Shenzhen Graduate School, Harbin Institute of Technology gave a lecture on the topic “Design in the Context of History Preservation”. On November 19, Mr. Kenneth Li, Director of Parsons Brinckerhoff (Asia) Ltd. gave a lecture on the topic “LEED – The Path to Green Buildings”. On April 1, 2011, Mr. Thomas Chung, Assistant professor of School of Architecture, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, gave a lecture on the topic “Urban Process in Hong Kong: Morphology, Type and Urban Living”. On April 14, Mr. Jorge Figueira, Director of the Department of Architecture of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra, Portugal, gave a lecture on the topic “Introducing the 2011 Pritzker Prize: Eduardo Souto de Moura”.

AAM CPD SEMINAR

Architecture as Cultural Practice?Date:

Objective:

Speakers:

Abstract:

持續專業發展課程 CPD Seminar

36

November 19, 2010

Introduction on requirements, approach and cases for LEED certifi cation

Mr. Kenneth Li – Director, Parsons Brinckerhoff (Asia) Ltd.

Building design with green practices has been gaining increasing attention to address the global issues relating to climate change, energy shortage, and excessive carbon emission due to consumption of fossil fuels, scarcity of potable water, material, and resources and so on. Green building practices can signifi cantly reduce or eliminate negative environmental impacts through high performance, market-leading design, construction, and operations practices. They can also reduce operation costs, enhance building marketability, and increase workers’ productivity resulting from good indoor air quality.LEED (The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is the most worldwide popular green building rating system being adopted in various countries including Asian cities like Hong Kong, South Korea and Mainland China. Through LEED compliance, green building practices can be injected as important ingredients throughout the whole life cycle from design, construction to operation.

AAM CPD SEMINAR

Design in the Context of History ReservationNovember 6, 2010

The lecture aims to help the Architects be more aware about the importance of designing with the consciousness of urban context, rather than only focusing on personal expression. Especially in a complicated historical context, the challenge of creating harmony between old and new may be turned into the origin of Architect’s inspiration.

Dr. Xiangmin Guo, Vice-Director, the Center of Urban and Landscape Design, the Shenzhen Graduate School of Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen

When making designs in the complicated historical context, Architect always faces severe challenges to coordinate the dialogue between traditional and modern constructions. Especially in a city of remarkable historical value like Macau, the Architects will fi nd the same dilemma as those working in mainland China. Here we present a typical case in Guangzhou, which try to create an unusual harmony between the old Sun Yat-sen’s Mansion and the new surroundings.The Sun Yat-sen’s Mansion is an important historical building preserved by both national and local governments. However, the surroundings of the Mansion are terrible since it is surrounded by a high-rise viaduct which serves as part of the cross-river bridge. Some experts of history preservation suggest that the viaduct should be eliminated in order to recover the previous environment of the Mansion and to provide more comfortable public space for people, but the experts from transportation study argue to keep the function of the viaduct so that the traffi c stress across the river can be effectively mitigated. Thus here comes the challenge for us: designing in the context of history preservation always needs to balance with the current city function or life style. Then how to create a more attractive environment for the historic building while keeping the city traffi c going well? The lecture will introduce our ideas of how to merge the controversial items into one design scheme.

AAM CPD SEMINAR :

LEED – The Path to Green Buildings”

Date:

Objective:

Speakers:

Abstract:

Date:

Objective:

Speakers:

Abstract:

37

April 01, 2011

The seminar introduces a methodology of urban investigation and analysis that use both morphology and building type to examine urban process. Using specifi c cases from Hong Kong, it will highlight how contextual architecture and “space between buildings” are integral to urban living, and how architectural design must contribute to the making of public places.

Prof. Thomas Chung, Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, the Chinese University of Hong Kong

This talk traces Hong Kong’s rapid post-war transformation from the perspective of urban living by examining how changes in city morphology and housing type affect the place of work, open space provision, street life and urban experience. Selecting areas with historical fabric on Hong Kong Island such as Sai Ying Pun, Sheung Wan and Central as case studies, the process of urban change is studied at the scales of the city district, the street block and the individual building, to evaluate how each scale interface with and affect one another. From the ever-increasing scale and pace of urban development, demands on economic return as well as preoccupations with individuality, questions concerning how architecture as a place of living can relate to the urban context will be addressed. The much-publicized, controversial redevelopment of Wing Lee Street in Central will be discussed to identify persisting problems of urban redevelopment as well as possible alternative strategies to deal with current architectural and planning practices in Hong Kong. Finally, the talk will discuss how this urban investigation methodology has informed the underlying pedagogy of an architecture design studio that emphasizes contextual response and place-making in the contemporary city.

April 18, 2011

The aim of this seminar is to present the work of Eduardo Souto de Moura, the Portuguese architect who won the Pritzker Prize 2011. We will show his main projects and discuss the distinctive elements of these works in terms of modern and contemporary architectural culture.

Prof. Jorge Figueira, Assistant Professor, Director of the Department of Architecture of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra, Portugal

This talk traces the work of Eduardo Souto de Moura, the 2011 Prizker Prize winner, beginning with his collaboration with Alvaro Siza, which was followed by a very thought out career in the late 70s, taking the work of Mies van der Rohe as a model. The big question has become, in the mid-1990s, how his experiences and individual language, developed in the scope of family house programs, would support the move to a larger scale and increased complexity of other programs. The response was reiterated by the uniqueness of the course, consolidated step by step. It began with works of rehabilitation (Pousada de Bouro, Value Chain), followed by the intervention on an urban scale (Braga Stadium, Metro do Porto, Burgo). And then, with equal success, building the “iconographic” - the House of Stories Paula Rego, in Cascais. And even now, this course continues with projects in Naples (with Siza), Barcelona, Belgium or Abu Dhabi. What does distinguish the work of Souto de Moura? He was always motivated by good solid construction, perhaps by a more direct infl uence of Fernando Távora, the Oporto Master, than by Mies. In the country of painted plaster, materials and constructive detail, the use of stone, iron and concrete, allowed a remarkable strength, both apparent and real. In cultural terms, the work of Souto de Moura reintroduces in our time, expressions of modern vanguard of the early 20th century with a domesticity and comfort that eluded the original models. In the international context, he is one of the architects of the transition from a more performative avant-garde to the glamorous images of a minimalist lifestyle.Souto de Moura´s focus on “discipline” - the detail, construction, structure - competes with a playful side and fl uent contemporary taste illustrated by the quotes and paste. After a sequence of very diverse projects, the Casa do Cinema Manoel de Oliveira, in Oporto, marked the start of a new stage in the work of Souto de Moura. A more exploratory phase, opening up what he had so explicitly closed; “out of the box” both in a metaphorical and in a literal sense. Since then it has been very interesting to follow a kind of struggle that his work translates between the tradition of the robust and the more organic and liquid forms that contemporary architecture “requires”.

Date:

Objective:

Speakers:

Abstract:

Date:

Objective:

Speakers:

Abstract:

AAM CPD SEMINAR

Introducing the 2011 Pritzker PrizeEduardo Souto de Moura

AAM CPD SEMINAR

Urban Process in Hong Kong: Morphology, Type and Urban Living

38

39

40

41

42

Lançamento do Livro: História da Arquitectura na Índia, Indonésia e sul da ChinaOrganização: Jeronimo de Paula da Silva e Maria Clara Amado Martins

Autores: Maria Clara Amado, Olinio Gomes Coelho, Rui Leão, Maria José Peitosa e Carlos Gonçalves Terra

Edição: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)

Local: Sede da Fundação Oriente (Casa Garden)

Data: 6 de Dezembro de 2010

READ

43

arcasia

SPONSORED BY