“Yes, a T-Shirt!”: Assessing Visual Composition in the “Writing” … · “Yes, a...

Transcript of “Yes, a T-Shirt!”: Assessing Visual Composition in the “Writing” … · “Yes, a...

W197

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

CCC 61:1 / september 2009

Lee Odell and Susan M. Katz

“Yes, a T-Shirt!”: Assessing Visual Composition in the “Writing” Class

Computer technology is expanding our profession’s conception of composing, allowing visual information to play a substantial role in an increasing variety of composition assignments. This expansion, however, creates a major problem: How does one assess student work on these assignments? Current work in assessment provides only partial answers to this question. Consequently, this article will review current theory and practice in assessment, noting its limitations as well as its strengths. The article will then draw on work in both verbal and visual communication to explain an integrative approach to assessment, one that allows instructors to consider students’ work with visuals without losing sight of conventional goals of a “writing” course. The article concludes by illustrating this approach with an analysis of an unconventional student text—a T-shirt—that students submitted as the final assignment for a relatively con-ventional writing course.

You’ll hear a good bit more about the T-shirt later in this article, where we show the T-shirt, describe its visual and verbal features, and use it to illustrate a theoretical basis for assessing students’ efforts to integrate visual and verbal information in a writing class. But for now, suffice it to say that the students who created the T-shirt were more enthusiastic about it than was their instructor.

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 197 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W198

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

They had persuaded their reluctant instructor to let them submit the T-shirt as part of an assignment for a course titled Rhetoric and Writing, not a course in graphic design. Granted, the instructor assumed that the final assignment would represent a departure from earlier assignments, which consisted of reports and analyses of exemplary written texts. The students were, after all, assigned to find a client and apply rhetorical concepts from the course in creat-ing a document that would serve the needs of the client’s organization—a local Boys and Girls Club, for example, a campus organization, or a local historical society. Most of the students did exactly what their instructor had expected, working with a non-governmental organization to compose relatively con-ventional texts (pamphlets, brochures, newsletters) in which images and page layout complemented a written text consisting of sentences and paragraphs. The T-shirt, however, had an unanticipated commercial purpose and contained somewhat fewer than two hundred words, none of which comprised sentences. The rhetorical effect of the T-shirt depended at least as much on its layout as on its verbal content.

Although the T-shirt was created almost a decade ago, it anticipates a point of view that is becoming prevalent in our profession: We can no longer equate composing with writing. Whether we are working with digital media or conventional print media, we can’t continue to assume that, as Anne Frances Wysocki puts it, “content is separate from form, writing from the visual, infor-mation from design, word from image” (138). Instead, we have to recognize that composing entails not only the obvious elements of visuals—photographs, drawings, charts, graphs—but also all aspects of the “materiality” of a text—type style, size, and boldness, for example, as well as page layout.

For writing teachers this interest in visual communication may seem a mixed blessing. It expands the range of composition assignments instructors can give, and it opens a new realm of communicative resources that students delight in using. Thanks to computer technology, they can manipulate color, typography, page (and screen) layout, and images in ways that once were pos-sible only for graphic designers (see, for example, George; Hocks; Selfe; Shipka). The problem for “writing” teachers is that this sort of work leads them into what for most will seem unfamiliar territory, especially as they try to assess students’ work. Instructors may have intuitions that a particular page design doesn’t quite “work,” or that an image seems particularly effective (or ineffec-tive). But how do they articulate the basis for their intuitions? That is, how do they assess students’ use of visuals? And how do they manage to integrate this sort of assessment with their assessment of written work?

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 198 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W199

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

Answers to such questions as these are more readily available than they might seem. These answers come in part from current work in assessment, which articulates principles that can be used in assessing both visual and verbal communication. Other answers come from current work in rhetoric and compo-sition, which closely parallels work in visual semiotics and graphic design. The chief difficulties in formulating these answers come from two sources. What would appear to be widely accepted principles for assessment are contested and/or subverted in assessment practice. Further, work on assessing writing has not capitalized on ways in which work in visual communication can inform the assessment of texts that integrate visual and verbal information.

After explaining these difficulties, we will illustrate an approach to assess-ment that we believe can guide the assessment of any multimodal composi-tion—videos or websites, for example, as well as written essays that incorporate visuals. As will become clear, we are not concerned with large-scale assessment, but rather with the assessment that serves the day-to-day work of helping students improve their ability to compose.

Assessment Theory and PracticeMuch of the groundwork for what we want to say has already been laid in other discussions of assessment theory and practice, especially when these discus-sions focus on the assessment that goes on in classrooms. These discussions usually emphasize formative assessment (Brian Huot uses the phrase instructive evaluation [69]) rather than summative assessment. That is, there is less concern with grading or ranking students and more attention to the assessment that occurs throughout the composing process, from the early stages of gathering and reflecting on information through the late stage in which students write self-assessments of their completed drafts. Further, discussions of assessment acknowledge the importance of understanding students’ perspective on their own work, and these discussions are beginning to include efforts to assess students’ ability to communicate visually as well as verbally. However, current work on assessment is more problematic than it might seem.

Formative AssessmentThere is little disagreement about the importance of providing students with formative assessment, helping them see what is working well in their writing and what they might do to make it better. But how much help can we—and should we—provide? There are limits to the help instructors can provide. Much as students might sometimes want it, there is no way to reduce composing to

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 199 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W200

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

an algorithm that leads inevitably to an excellent piece of work. And even in trying to provide guidance, it is important not to take “control” of a student’s work. (See Brannon and Knoblauch; Fife and O’Neil; Straub.)

Nonetheless, students do need guidance as they formulate and articulate their ideas (perceptions, feelings, values). Moreover, they need guidance that, in Nancy Sommers’s words, “our students will take with them as they move from our class to the next, from one paper assignment to another, across the draft” (248). Thus the language of assessment must be both generative and generalizable. Unfortunately, much of the language of assessment is neither.

Consider, for example, the judgment that a student needs to do a better job of organizing and elaborating, an injunction implicit in comments Robert J. Connors and Andrea Lunsford found frequently appearing in teachers’ assess-ment of student papers (203). What is the student being asked to do to improve organization? Establish a clear causal or temporal sequence of events? Group information around specific topics? Use terms that will forecast subsequent sections of a text?

Further questions arise with the request to “elaborate.” How much and what sort of information is the student supposed to provide? Where does he or she look to find that sort of information? How much elaboration is enough? How does the student decide whether a particular bit of elaboration (a detail, a quotation, a reference to an authority) is appropriate?

And even if a student gets an answer that pertains specifically to the task at hand, how does that answer pertain to writing in other contexts? Almost certainly what counts as appropriate organization and elaboration in a per-sonal narrative differs from that which is needed in, say, a laboratory report. So how do writing instructors provide assessments that are both generative and generalizable? Our answer to that question will depend in part on what we can say about students’ perspectives on their work and about the relations between visual and verbal communication.

Students’ PerspectivesIn the title for an article on responding to student writing, Sandra Murphy poses an interesting question: “Is there a student in the room?” Her assumption is one that appears frequently in discussions of assessment: any effort to assess student work must take into account students’ perspectives on that work. Although Murphy is concerned with students’ understanding of teachers’ comments, current work on assessment provides at least two other means of identifying

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 200 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W201

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

students’ perspectives: viewing that work in terms of its rhetorical context, i.e., the purposes students hope to achieve and the audience they hope to reach, and considering students’ assessment of their own work. In both cases, there is a considerable gap between assessment theory and practice.

Rhetorical ContextFor much of the twentieth century, instruction in composition was governed by a “practical stylist” rhetoric that made little or no reference to audience or purpose. Thus it is not surprising that early work in writing assessment did the same. (For an overview of this approach to assessment, see Cooper 4–11.) More recently, however, discussions of assessment have begun to emphasize the importance of audience and purpose. Brian Huot makes the point clearly: “Assessment practices need to be based on the notion that we are attempting to assess a writer’s ability to communicate within a particular context and to a specific audience who needs to read this writing as part of a communicative event” (102).

Ironically, current discussions of the importance of audience and purpose bring us back to Murphy’s question about whether there is “a student in the room.” At least as far as analysis of rhetorical context is concerned, the answer would appear to be no. Discussions of assessment never indicate that students themselves should be expected to identify salient features of the audience they are addressing or articulate the specific purpose they hope to accomplish. Occasionally, students are asked to address a general category of readers—class-mates, say, or some nonacademic group such as a local school board. But they are never asked to specify their assumptions about what a particular audience might know, assume, or value with respect to a particular topic.

Granted, there are times when a writer might put aside considerations of audience (see, for example, Elbow, “Closing My Eyes”). Further, there may be situations (for example, in emails, personal letters, routine reports) in which a writer is so familiar with a particular rhetorical context that an understand-ing of that context is simply part of the writer’s tacit knowledge and thus does not need to be made explicit. But when the rhetorical context is unfamiliar or especially challenging—as is often the case when students compose—assump-tions about that context need to be made explicit so that they can be examined and, if necessary, revised.

To be more specific, we argue that both student and teacher will benefit when the student has answered such questions as the following: What assump-

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 201 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W202

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

tions is it reasonable to make about the knowledge, values, attitudes, and prior experiences the audience is likely to bring to the text? What questions do they hope to find answered? Exactly what purpose(s) is the text intended to achieve? Granted, the general purpose may be, for example, to report information. But exactly why is one trying to report information? To reassure readers on a topic they find troublesome? To make them aware of a problem they hadn’t consid-ered? To explain a solution to a problem that is on their minds? Lacking answers to these questions, it is difficult to conduct the student-teacher “conversation” Murphy thinks is essential for formative assessment.

Self-AssessmentAs is the case with rhetorical context, there is widespread agreement about the role of students’ self-assessment of their work. As early as 1977, Mary H. Beaven argued that students can and should engage in this sort of assessment, if only responding to a rather general request to identify strengths and weaknesses of their work (142–48). More recently, Huot has pointed out that “being able to assess writing is an important part of being able to write well. Without the ability to know whether a piece of writing works or not, we would be unable to revise our writing or to respond to the feedback of others” (165).

Consequently, it makes good sense to follow a practice described by Edward M. White, in which students are required to compose a “reflective let-ter” that will directly bear on students’ grades: “a well written, reflective letter with partial or missing support in the portfolio will not receive a high grade nor will a poorly written reflective letter with good support” (593). Unfortunately, this is the exception rather than the rule. At least in published discussions of assessment, students’ self-assessments rarely figure into the overall judgment of students’ writing.

Assessing Visual and Verbal CompositionAs we were writing this article, we found only two examples of how one might as-sess compositions that include both visual and verbal information. The first, by Don Payne, Quinn Warnick, and Donna Niday, is intended to assess a “four-year multimodal curricular plan for strengthening undergraduate communication learning at Iowa State University.” This assessment reflects a broad definition of communication, one that includes oral and electronic communication as well as visual and written. It also provides terms that constitute a lens through which composition in each medium can be viewed. For example, in assessing the substance of student work in any of the four media, assessors are asked

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 202 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W203

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

to consider the “scope,” “depth,” “relevance,” and “fairness” of the visual, oral, electronic, and verbal information students present.

This program assessment is impressive not just in its comprehensiveness but also in the extent to which it makes use of terminology from graphic design and visual communication. The only reservation we have with this assessment scheme comes from what we see as its principal strengths—its comprehensive-ness and complexity. The procedure seems well suited for program assessment, but perhaps less so for individual assessment, given the time constraints of daily instruction.

A briefer guide to assessing visual communication comes from Sonya C. Borton and Brian Huot. They assert a point implicit in our comments thus far: “all multimodal assignments, all instruction in the use of digital and non-digital composing tools, all assessment of multimodal compositions, should be tailored to teaching students how to use rhetorical principles appropriately and effectively” (99). Toward this end, they identify a series of “possible criteria for formative assessment.” In addition to criteria related to rhetorical context (purpose, audience, and tone), Borton and Huot point out that successful compositions should include “transitions to guide the audience effectively from one set of ideas to another” and “detailed description, examples, sound, music, color, and/or word choice to convey ideas in an effective and appropriate way to the audience” (101).

The emphasis on audience and purpose is consistent with current thinking in assessment theory as well as in composition instruction. And certainly these criteria have the generalizable quality we discussed earlier. For example, it is usually appropriate to choose details and language that will convey one’s ideas in a way that is appropriate for a particular audience. Their criteria, however, are problematic in a couple of ways. For one thing, the criteria Borton and Huot propose are not informed by work on visual communication. As Karen Schriver has shown, visuals and verbal text may be related in ways (see, for example, the discussion of “stage setting” below) that are not marked by transitions. Further, Borton and Huot’s criteria lack the generative quality we mentioned earlier. How does one, for example, identify salient features of a visual image and determine whether those features are appropriate for the intended audi-ence? How does one choose specific elements of format—typography, white space, inset boxes—that will contribute to the overall effect of a composition? What principles should guide the inclusion of still and/or moving images in a verbal text?

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 203 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W204

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

Integrative AssessmentAny effort to integrate the assessment of visual and verbal information will, of course, have to meet the standards suggested by our analysis of current assess-ment theory and practice. It will need to be grounded in students’ analysis of their rhetorical context, influenced by the quality of students’ self-assessments and expressed in language that will be both generalizable and generative. It will also have to be as applicable to visual communication as to verbal. Later we will identify a set of conceptual processes that underlie both visual and verbal communication and that provide a basis for this sort of assessment we want to propose. But first we have to acknowledge some formidable obstacles to this integration.

The first obstacle is terminology. Much of the language of, say, graphic design is different from the language of composition and rhetoric. And even when writing teachers and graphic designers use some of the same terminology, those terms don’t always have the same meaning. When, for example, graphic designer Donis A. Dondis uses the term tone, she means “intensity of dark-ness or lightness of anything seen” (47), not the attitude or voice composition instructors are referring to when they talk about tone.

Problems with terminology are compounded by other theoretical prob-lems. Even scholars whose work holds great promise for integrating visual and verbal information advise caution in this effort. Charles Kostelnick and David D. Roberts, for example, show how one set of terms or “cognates” can help describe both visual and verbal elements of a text (14–22). But even while acknowledging the value of such cognates, Kostelnick and Michael Hassett add this caution: “analogies between the visual and the verbal are necessarily limited because the two differ in their form, syntax, and origin as well as the ways in which readers perceive and interpret them” (1). Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen make a similar point: “the differences [between the media] are greater than the similarities” since “the visual semiotic has a range of structural devices which have no equivalent in language” (115). And Kress goes even further, arguing that the logic of verbal communication is different from that of “the logic of the image.” Elements of verbal logic “unfold in time and sequence,” whereas “the elements of the image are related in spatial arrangements, and they are simultaneously present” (20).

Conceptual ProcessesFormidable as these problems are, we argue that they can be overcome with an understanding of four basic conceptual processes: moving from given informa-

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 204 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W205

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

tion to new, creating and fulfilling expectations, selecting and encoding, and identifying logical/perceptual relationships. We will show why we think these processes are as important for visual communication as they are for verbal.

The phrase conceptual processes may raise a couple of issues. The word conceptual may seem to denote the cognitive, purportedly dispassionate activity that is often thought to exclude perceiving, valuing, or responding emotionally. But as part of his work on the psychology of art, Rudolf Arnheim specifically challenges the distinction between cognition and perception, contending “the cognitive processes called thinking are not the privilege of mental process above and beyond perception but the essential ingredients of perception itself ” (13). And although Kress and van Leeuwen talk about the “logic” of visuals, their discussions of visual images greatly expand the definition of this logic, frequently referring to perceptions, values, and personal responses as well as more impersonal intellectual activities (e.g., 155–58).

A second concern may arise with the term process, a term that can suggest the moment-to-moment processes one engages in while drafting and revising a text. Trying to use a completed text to understand all these processes would be, in a memorable phrase we have heard attributed to Donald Murray, like trying to infer a pig from sausage. Fair enough. Some aspects of the processes of thinking/perceiving/responding are mysterious. And as Murray illustrates in examples of his own composing process, even the conscious elements of composing (as manifested in revisions of a text, for example) may never ap-pear in a completed product, whether written or visual (55–62). However, a completed product does reflect epistemic choices, decisions that affect both the substance of a message (verbal or visual) and the way that message is ex-pressed. The process of making these choices may be intuitive, spontaneous, and sometimes inaccessible. But these choices do get made. And some of the significant ones appear in a completed text.

Moving from Given to NewIn his work on syntax, Joseph M. Williams points out that one important way writers can make their sentences cohesive is to observe what linguists refer to as the “given-new contract,” by beginning sentences with given (Williams uses the term old) information, either that which has been established in preceding sentences or that which a reader possesses prior to reading a particular text. Then, especially at the end of a sentence, writers introduce new information that expands on readers’ understanding of the given (75–78).

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 205 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W206

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

Janice C. Redish extends Williams’s discussion of given and new. She summarizes research showing that readers never approach new experience as a blank slate. Instead, they interpret new information in light of “givens,” a body of expectations, existing knowledge, values, biases, feelings, questions, knowledge of disciplinary conventions, and assumptions (31). Thus one of a writer’s main tasks is to “make explicit connections to readers’ prior knowledge and expectations” (i.e., the givens with which they approach a text) and then provide new information that will expand readers’ knowledge.

Despite their understanding of differences between visual and verbal in-formation, Kress and van Leeuwen explain how the given/new contract applies to visual communication, whether in fourteenth-century paintings, diagrams, or advertisements (186–92). As one example, they cite an ad for a computer. On the left-hand side of the ad, just under the slogan “Organization at your fingertips,” appears a given, the familiar image of a notebook computer. Just to the right of the computer is another given, a detail from a painting readers should recognize: Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam,” in which God is reaching out to touch and give life to Adam. The detail consists of the arm and hand of God, fingertips reaching out not to Adam but to the computer. The details are familiar, but their use in this context constitutes something new.

In the case of the ad, it’s fair to assume that this use of given to new is a conscious choice, even if it originated in a moment of inspiration. But for purposes of this discussion it does not matter whether or not the choice was made consciously. Anyone who writes—or paints or composes music or creates an ad—has access to a wide range of alternatives, among them diction, details, harmonic structure, color, and so on. Inevitably, choices have to be made, and each is likely to be an epistemic choice, one that shapes and conveys meaning. These epistemic choices appear in any text, visual or verbal.

Creating and Fulfilling ExpectationsAs we noted earlier, one of the givens with which readers may approach a text consists of one or more expectations about the content of a text or the attitudes it will display. These expectations not only draw readers to a text but also guide their reading of that text. That is, readers make inferences about what they may expect to find and then determine how (or whether) those expectations are fulfilled. Writers want to have some influence on this reading process, helping readers see what they may expect and then, as a rule, fulfilling those expecta-tions. Peter Elbow makes our point this way: “Successful writers lead us on a journey to satisfaction by way of expectations, frustrations, half satisfactions,

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 206 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W207

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

and temporary satisfactions: a well-planned sequence of yearnings and reliefs, itches and scratches” (“Music of Form” 626).

Elbow acknowledges that some of the guidance for this journey may come from traditional “signposts”—thesis statements, for example, or topic sentences. But Elbow is principally interested in what he calls “dynamic organization” (“Music of Form” 644), patterns of discourse that “bind” a text together. These patterns may include “Most people think . . . , but really . . .” and “It used to be . . . , but now . . .” (636). The first phrase leads readers not only to expect a sum-mary or at least an acknowledgment of what “most people think,” but also a discussion of what the writer thinks is “really” the case. Elbow also mentions the role of “perplexity” (638–40) and “voice” (642–44) as means of guiding readers along the journey that entails creating and fulfilling expectations. As Elbow notes, there may be instances in which expectations are only partially fulfilled—or even thwarted. But it seems fair to assume that these instances should probably be the exception rather than the rule.

In addition to using signposts and relying on patterns of discourse (e.g., “Most people think . . . but really”), writers can also use visual cues to guide a reader’s expectations. Schriver talks about the “stage-setting” function of im-ages. A visual image, especially when it accompanies the title of an article, can help readers anticipate not only the content of that article but also the writer’s attitude toward or perspective on that content (425). Kostelnick and Hassett have shown how visual elements—typeface, color, layout—can help readers anticipate what a writer thinks is important, make inferences about the tone they may expect to find in a written text, and even draw some initial conclu-sions about the credibility of information they will find in a written text. And Redish has pointed out how other visual elements—headings, pull quotes, inset boxes—can guide the reading process, showing readers what sort of content they may expect to find in a given passage of text.

Selecting and EncodingAs part of observing the given/new contract, writers have to engage in a pro-cess that psychologist Robert J. Sternberg terms “selective encoding” (89–91, 185–87). Sternberg argues that to understand anything, we “separate the wheat from the chaff ” (185), selecting relevant information and discarding the rest. We are guided in this winnowing process, Sternberg suggests, by the way we encode information, i.e., by the connotations and assumptions implicit or explicit in the language we use to represent information (ideas, thoughts, perceptions), whether to ourselves or to others. In his explanation of encoding, Sternberg

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 207 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W208

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

talks only about ways an individual’s personal assumptions and associations guide his or her understanding of information. But individuals are members of various discourse or disciplinary communities, any of which may have its own discourse conventions, and the assumptions and associations implicit in those conventions may also guide an individual’s effort to communicate about a topic or understand information.

Sternberg does not suggest that selective encoding might appear in visual information, but the concept, if not the specific phrase, appears in discussions of visual communication. Kress and van Leeuwen, for example, show how cultural assumptions appear in two apparently innocuous pictures in a social studies textbook intended for students in Australian primary schools.

Both pictures show tools used by two Australian cultures, that of the Aborigines and that of the British. But the picture of the Aborigines’ tools shows only those tools, omitting any images of the context in which those tools have proved highly useful. The British tools, by contrast, are shown in a physical context or scene that suggests the power associated with British tools. Several figures, presumably British, are shown carrying guns as they approach (Kress and van Leeuwen use the term stalk) what would appear to be a group of Aborigines gathered around a campfire at night. Kress and Van Leeuwen point out that British figures are represented (i.e., encoded) in ways that suggest the dominance of British culture: they are relatively large, located in the foreground of the picture, and shown in postures that suggest action. This image reflects a larger cultural narrative in which the British are shown as actors, dominating the Aborigines, who are considered merely the goal or object of British actions (43–45). (See also Lidwell, Holden, and Butler [38]; Kostelnick and Hassett [183].)

Logical/Perceptual RelationshipsOf all the concepts mentioned thus far, these relationships will be most familiar to composition instructors. Represented in a line of work beginning with Aris-totle’s common topics and continuing in widely used composition textbooks (see, for example, Lunsford, Ruszkiewicz, and Walters), these relationships include comparison and contrast, classification, location in a setting or scene, and temporal and causal sequence. Important as they are in composition stud-ies, they are equally important in visual communication. (For a discussion of ways these relationships can figure into assessment of students’ written work, see Odell, “Assessing Thinking” and “Measuring Changes.”)

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 208 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W209

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

Edward R. Tufte, one of the preeminent authorities on information design, shows the importance of two of these relationships for two significant sets of visual information, one successful—a “graphical display” of information that helped identify causes of a cholera epidemic in nineteenth-century London—and several others that were disastrously unsuccessful—charts and tables that led NASA to go ahead with the launch of the space shuttle Challenger (“Visual Explanations” 27–43). The success of the former and the failure of the latter were directly related to the extent to which they clearly illustrated causal con-nections that enabled viewers to make “quantitative comparisons” (29–30). In his most recent book, Beautiful Evidence, Tufte asserts that the ability to “show comparisons, contrasts, differences” is “the first principle for the analysis and presentation of data” (126–28). The second has to do with “causality, mecha-nism, structure, [and] explanation” (128–29). (For other illustrations of logical/perceptual relationships in visuals, see Schriver, 306–12; Horton, 195–96; and Dondis, 32–38.)

Implications for AssessmentWe turn now to student work to show how the preceding discussion can in-form assessment. Since we agree with Murphy that assessment should show that there is, in fact, “a student in this class,” we will rely heavily on students’ self-assessments to illustrate the conceptual processes we have discussed and show how an understanding of those processes, combined with an explicit statement of rhetorical context, allow assessment that is both generative and generalizable. Although students wrote their comments when they had com-pleted a final draft of their project, these comments referred to most of the conceptual processes, explained earlier, that had been emphasized throughout the process of creating the T-shirt—indeed, throughout the entire course. (The logical processes—classifying, etc.—were not a main theme of the course; ref-erences to these processes occurred essentially in an ad hoc manner, as they seemed appropriate for a specific student’s work on a particular assignment.)

Yes, a T-Shirt!The T-shirt was the product of a (usually) good-natured negotiation between an instructor and a team of four students: Brian Boswell, Stephanie Noble, Denys Petrina, and Andrew Wolcott. For this final assignment of the term, as for those assignments that preceded it, each student had to submit a self-assessment explaining how he or she had analyzed rhetorical context, moved from given to

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 209 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W210

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

new, selected information, represented that information visually and verbally, and created and fulfilled expectations. The triumphant phrase Yes, a T-shirt! comes from the title Stephanie gave to her self-assessment of the T-shirt. (When the instructor looked through his files for students’ analyses, he found work from only three of the four students—Brian, Stephanie, and Andrew. But after ten years, three out of four isn’t bad.)

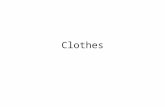

The front of the T-shirt—printed in the red, white, and blue colors associ-ated with the iconic figure of Uncle Sam—consists of a map showing only the main intersecting streets of downtown Troy. The figure of Uncle Sam displays a couple of familiar details—top hat, striped trousers—but also what Andrew referred to as a “Dr. Seuss-esque” quality. The typeface in which the word Troy appears is the one used, without the cartoon face of Uncle Sam, on all the city’s promotional materials. A similar allusion to the city’s promotional

Figure 1. Front of T-shirt showing map of downtown Troy, highlighting businesses of interest to their audience, undergraduates at their university. Numbers on the T-shirt refer to specific businesses listed on the back of the T-shirt.

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 210 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W211

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

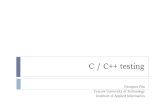

materials appears in the use of the Troy logo on the shopping bag Sam is carrying. The back of the T-shirt lists a number of downtown businesses, arranged in two columns, grouped under headings (eating out, nightlife, etc.) that would be of interest to students. Between the two columns are other cartoon im-ages of Uncle Sam.

Assessing Rhetorical ContextBrian, Stephanie, Denys, and Andrew began their project with the goal of encouraging on-campus students at their university to patronize busi-nesses in downtown Troy, New York, a small, post-industrial city that had fallen on hard times but still took pride in referring to itself as “the birth-place of Uncle Sam.” In creating this T-shirt, Brian, Stephanie, Denys, and Andrew said they

Figure 2. Back of T-shirt listing downtown businesses by category. Numbers with each business correspond to numbers found on the map on the front of the T-shirt.

had to appeal to three different audiences: their instructor, who wanted to be sure students could apply concepts from the course; their client, the Deputy Mayor of Troy, who appreciated what one student referred to as an “off the wall” sense of humor but didn’t want the T-shirt to offend local businesses; and their primary audience of fellow students who lived on campus.

The instructor initially discouraged students from trying to appeal to such a large, diverse audience. However, as part of the ongoing conversation about the assignment, Stephanie and her partners persuaded the instructor that their primary audience was likely to share several experiences and char-acteristics. Especially at the beginning of the semester, on-campus students were deluged by what Brian referred to as “a thousand forms of media flying

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 211 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W212

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

at every student and clawing for their attention.” Thus a brochure or a flyer wouldn’t work. Further, the T-shirt team noted that most on-campus students had little positive information about the town, other than a vague memory, based on Student Orientation during the summer before their first year, that the town claimed to be the birthplace of Uncle Sam. Their negative impressions, however, were strong. As Brian puts it: “Why the hell would anyone want to go to downtown Troy? The place is a dump, and there’s nothing there unless you want to get trashed.”

Using Conceptual ProcessesThis audience analysis led Stephanie and her partners to identify several givens they could build on. If on-campus students were unhappy about, in Brian’s words, “wasting a lot of time, gas, and money” to go shopping at one of two local malls located about a half hour’s drive from campus, they might be glad to know that just by walking five minutes to downtown Troy they could find many of the resources they wanted. After all, as Brian pointed out, “Actually, there’s some cool stuff in downtown Troy . . . [b]esides the obvious numbers of bars, pizza places and established hangouts, [Troy has] unique clothing stores that had great stuff to offer but not that many customers . . . [and] a cyber café . . . along with a pawn shop where you could pick up a cheap Nintendo 64 or games [this was ten years ago, remember]. There’s a great used furniture store down there, too!”

Further, if students were often annoyed by flyers and brochures, they might appreciate—or at least not discard out of hand—information conveyed in a different medium, in this case information presented on clothing they preferred to wear. And given their negative attitudes toward Troy, on-campus students would be unlikely to take seriously any literature that made too earnest a case for the benefits of the downtown area. They might, however, respond to what Andrew referred to as “tongue-in-cheek” humor that entails mild irreverence and a sense of incongruity.

To build on these givens, the T-shirt team relied in part on the way they sequenced information on the T-shirt. As Stephanie points out, the lists of businesses on the back of the T-shirt “move from given to new in that they be-gin with an easily recognizable phrase (such as shops) and then move to more and more specific new information (the business name and a description of what the business offers to the audience).” Further, Andrew points out, they established givens by including “only information that our audience would be interested in. This includes our selected list of businesses that could be useful

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 212 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W213

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

to our audience—not extraneous businesses like Thomasville Furniture, which would be too expensive for college students. . . . The brief information following the business names (where necessary) points out why the business would be useful/interesting to our audience, such as that anything can be found cheaply at the pawn shop [number 6 on the map].”

All three of the students commented on how their visual and verbal ele-ments tried to appeal to students’ sense of humor. Since they had to use the Troy logo, Brian points out that they “incorporated Sam, a spin-off of Uncle Sam drawn cartoon style. Sam has a large patriot hat with stripes and a star in the front center, a large nose and beard. The hat is oversized to the point where you can’t see his face. Sam has the appearance of a lovable little old patriot.” To further the comic image, Brian notes that they “put Sam downtown, running with a shopping bag, wearing a pair of JNCOs (baggy pants), drinking beer, and sporting some phat [again, this was ten years ago] new sneaks.”

Given the nature of the information they were presenting, it is not surpris-ing that students had little to say about conceptual/perceptual relationships such as causal sequence or location in a physical context. However, in her self-assessment, Stephanie points out that she and her partners had categorized information about the town, using different sizes and colors of the typeface to help separate the information and make it more easily readable. And Andrew notes that “the category headings on the back [of the shirt] create expectations as to the shirt’s content. Each category, such as ‘nightlife’ includes related busi-nesses such as Elda’s (a club).”

In all this specific discussion of the T-shirt, we want to reiterate a point we previously mentioned almost in passing: the assessment procedure we have described is just as useful for assessing conventional print texts as it is for texts that rely heavily on visual information. In composing or assessing either kind of text, it is important to

• articulate one’s assumptions about audience and refine one’s sense of purpose;

• move from given to new within individual sentences and within larger sections of text;

• carefully select the amount and kinds of information to present;

• convey that information in language that makes sense given one’s audi-ence, purpose, and subject matter;

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 213 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W214

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

• create and fulfill expectations;

• learn to assess the extent to which one is achieving one’s intended pur-poses for an intended audience.

In addition to reiterating this point, we want to make explicit an assump-tion underlying the preceding discussion of the T-shirt: We continue to depend on the kindness (and the ingenuity) of our students. In persevering in creating and justifying the T-shirt, Andrew, Brian, Denys, and Stephanie had reason to share the triumph Stephanie expressed in the title of her self-assessment. They had created a highly effective text for a real client; they had prevailed in a disagreement with their instructor; and they anticipated, however unwit-tingly, a major development in their instructor’s field of study. Not bad for a few weeks’ work.

Works Cited

Arnheim, Rudolph. Visual Thinking. Berke-ley: U of California P: 1969.

Beaven, Mary H. “Individualized Goal Set-ting, Self-Evaluation, and Peer Evalu-ation.” Evaluating Writing: Describing, Measuring, Judging. Ed. Charles R. Cooper and Lee Odell. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1977. 135–56.

Borton, Sonya C., and Brian Huot. “Re-sponding and Assessing.” Selfe 99–111.

Brannon, Lilian, and C. H. Knoblauch. “On Students’ Rights to Their Own Texts: A Model of Teacher Response.” College Composition and Communication 33.2 (1982): 157–66.

Connors, Robert J., and Andrea Lunsford. “Teachers’ Rhetorical Comments on Stu-dent Papers.” College Composition and Communication 44.2 (1993): 202–23.

Cooper, Charles R. “Holistic Evaluation of Writing.” Evaluating Writing: Describing, Measuring, Judging. Ed. Charles R. Cooper and Lee Odell. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1977. 3–31.

Dondis, Donis A. A Primer of Visual Literacy. Cambridge: MIT, 1973.

Elbow, Peter. “Closing My Eyes as I Speak: An Argument for Ignoring Audience.” College English 49.1 (1987): 50–69.

. “The Music of Form: Rethinking Organization in Writing.” College Com-position and Communication 57.4 (2006): 620–66.

Fife, Jane Mathison, and Peggy O’Neill. “Moving Beyond the Written Comment: Narrowing the Gap between Response Practice and Research.” College Composi-tion and Communication 53.2 (2001): 300–21.

George, Diana. “From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing.” College Composition and Communication 54.1 (2002): 11–39.

Hocks, Mary E. “Understanding Visual Rhetoric in Digital Writing Environ-ments.” College Composition and Com-munication 54.4 (2003): 629–56.

Horton, William. “Pictures Please: Present-ing Information Visually.” Techniques for

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 214 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W215

o d e l l a n d k a t z / “ y e s , a t - s h i r t ! ”

Technical Communicators. Ed. Carol M. Barnum and Saul Carliner.Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1993. 187–218.

Huot, Brian. (Re) Articulating Writing Assessment for Teaching and Learning. Logan: Utah State UP, 2002.

Kostelnick, Charles, and Michael Hassett. Shaping Information: the Rhetoric of Vi-sual Conventions. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2003.

Kostelnick, Charles, and David D. Roberts. Designing Visual Language: Strategies for Professional Communicators. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1998.

Kress, Gunther. Literacy in the New Media Age. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Lidwell, William, Kristina Holden, and Jill Butler. Universal Principles of Design. Gloucester: Rockport, 2003.

Lunsford, Andrea, John J. Ruszkiewicz, and Keith Walters. Everything’s an Argument. 3rd ed. Bedford: New York, 2004.

Murphy, Sandra. “A Socio-Cultural Perspec-tive on Teacher Response: Is There a Student in the Room?” Assessing Writing 7.1 (2000): 79–90.

Murray, Donald. Write to Learn. 2nd ed. New York: Holt, 1987.

Odell, Lee. “Assessing Thinking: Glimpsing a Mind at Work.” Evaluating Writing: The Role of Teachers’ Knowledge about Text, Learning, and Culture. Ed. Charles R. Cooper and Lee Odell. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1999. 7–22.

. “Measuring Changes and Intel-lectual Processes as One Dimension of Growth in Writing.” Evaluating Writing: The Role of Teachers’ Knowledge about

Text, Learning, and Culture. Eds. Charles R. Cooper and Lee Odell. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1999. 107–32.

Payne, Don, Quinn Warnick, and Donna Niday. “Communication Assessment: A Multimodal Approach.” IWAC Confer-ence, Austin, TX, 29 May 2008.

Redish, Janice C. “Understanding Readers.” Techniques for Technical Communicators. Ed. Carol M. Barnum and Saul Carliner. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1993. 14–41.

Schriver, Karen. Dynamics in Document Design. New York: Wiley, 1997.

Selfe, Cynthia, ed. Multimodal Composi-tion: Resources for Teachers. Cresskill: Hampton, 2007.

Shipka, Jody. “A Multimodal Task-Based Framework for Composing.” College Composition and Communication 57.2 (2005): 277–301.

Sommers, Nancy. “Across the Drafts.” College Composition and Communication 58.2 (2006): 246–57.

Sternberg, Robert J. Intelligence Applied. San Diego: Harcourt, 1986.

Straub, Richard. “The Concept of Control in Teacher Response: Defining the Varieties of Directive and Facilitative Commen-tary.” College Composition and Communi-cation 47.2 (1996): 223–51.

Tufte, Edward R. Beautiful Evidence. Cheshire: Graphics, 2006.

. Visual Explanations. Cheshire: Graphics, 1997.

White, Edward M. “The Scoring of Portfo-lios: Phase 2.” College Composition and Communication 56.4 (2005): 581–600.

Williams, Joseph M. Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace. 8th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2005.

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 215 9/14/09 5:31 PM

W216

C C C 6 1 : 1 / s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 9

Wysocki, Anne Francis. “Impossibly Distinct: On Form/Content and Word/Image in Two Pieces of Computer-Based

Interactive Multimedia.” Computers and Composition 18 (2001): 137–62.

Lee Odell and Susan KatzLee Odell is a professor of composition at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he teaches courses such as Writing for Classroom and Career and Writing about Science. Currently he is working on assessment of nonprint compositions ranging from wikis and blogs to websites and digital narratives. Susan Katz is an associate professor of English at North Carolina State University, where she teaches under-graduate and graduate courses in technical communication and the rhetoric of science and technology. She is currently working on the integration of visual and verbal communication. She also coordinates the undergraduate and graduate internship programs for her department.

W197-216-Sept09CCC.indd 216 9/14/09 5:31 PM