ANGOLA gb 06 - OECD.org · disparities remain huge, with the Cabinda enclave and Luanda benefiting...

Transcript of ANGOLA gb 06 - OECD.org · disparities remain huge, with the Cabinda enclave and Luanda benefiting...

Angola

Luanda

key figures• Land area, thousands of km2 1 247• Population, thousands (2005) 15 941• GDP per capita, $ PPP valuation (2005) 3 363• Life expectancy (2000-2005) 40.7• Illiteracy rate (2005) ...

African Economic Outlook 2005-2006 www.oecd.org/dev/publications/africanoutlook

AngolaAll tables and graphs in this section are available in Excel format at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/344387777260

African Economic Outlook© AfDB/OECD 2006

107

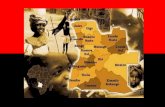

ANGOLA IS EXPERIENCING RAPID economic growth.Stimulated by high international oil prices and rapidlyincreasing output from new oil fields, real GDP growthexceeded 11 per cent in 2004 and, with oil productionset to surge still higher, growth is expected to increasefurther to about 15.5 per cent in 2005, 26 per cent in2006 and 20 per cent in 2007. While offshore oilexploration and production create very few linkages tothe rest of the economy, the sheer size of this sector– accounting for 50 per cent of GDP – providesopportunities for the construction industry and theincipient services sector, as well as recycling of oilrevenue through the government budget. Regionaldisparities remain huge, with the Cabinda enclave andLuanda benefiting much more from the boom than therest of the country, which remains isolated due to poorinfrastructure, limited progress with mine clearanceand slow resettlement of displaced populations andformer combatants. The consolidation of the peaceprocess is finally making it possible for the governmentand its development partners to proceed withinfrastructure reconstruction, agriculture recovery andsocial policies aimed at reducing poverty.

Considerable efforts have been made to improvemacroeconomic management. A less expansive fiscalpolicy, together with currencyappreciation, brought the rate ofinflation down from 43 per cent in2004 to an estimated 22 per cent in2005. Some progress has been madein consolidating and unifying thereporting of government revenue andexpenditure and in improving debt management.Although a much greater effort is required to improvefiscal transparency and balances, new sources ofinternational finance, in particular from China, havereduced the leverage of those in the international donorcommunity who have been pressing for more rapidreform.

The currently favourable external environmentmay pave the way for considerable progress towards theMillennium Development Goals (MDGs), but thereis a continuing need for greater transparency and long-term development planning, as well as additional effortsto improve the investment climate. The authorities

Oil is boosting Angolan growth but there is a need for greater transparency and better long-term developmentplanning.

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

2007(p)2006(p)2005(e)20042003200220012000199919981997

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Real GDP Growth (%) Per Capita GDP ($ PPP)

Figure 1 - Real GDP Growth and Per Capita GDP($ PPP at current prices)

Source: IMF and National Institute of Statistics data; estimates (e) and projections (p) based on authors’ calculations.

African Economic Outlook © AfDB/OECD 2006

108

Angola

now openly acknowledge that corruption is pervasiveand that better public management is key to reducingit. As the country approaches its first elections since1992, policy choices will come under closer scrutinyalthough, after three decades of external intervention,Angola’s government is sensitive to close monitoringby the international community and has preferred tonegotiate a Policy Support Instrument (PSI)1 with theIMF, allowing it to retain a higher degree of controlover macroeconomic policies. In order to fostersustainable long-term growth, it is crucial to includestructural reforms in the PSI with clear medium-termdeliverables and to demonstrate strong commitmentto implementation. Should this be achieved, thereappears to be support within the internationalcommunity for organising an investors’ conference.

Recent Economic Developments

Developments in the oil sector are driving thecurrently high rate of GDP growth. Although thissector has little direct impact on employment, createsfew direct linkages to other sectors of the economyand relies on imports of capital equipment andspecialised services, the pace of oil growth is bringingabout a construction boom. Moreover, new actors arechallenging the traditional dominance of the westernmajors and modifying the bargaining power of nationalauthorities.

Production in offshore fields, mostly in the Congoriver basin opposite the Cabinda enclave, totalled1.2 million barrels a day in 2005 and is expected to reach2.1 million barrels in 2008. In 2005, oil accounted formore than 52 per cent of GDP, 78 per cent ofgovernment revenues and 93 per cent of exports. In mid-2005, extraction started at the Kizomba B facility, theworld’s largest floating production, storage andoffloading vessel. With international prices rising,exploration is moving to ultra-deep fields, where bothtechnical difficulties and costs are much higher.

Government has traditionally intervened in the oilindustry through a state-owned enterprise, Sonangol,which retains responsibility for contract negotiations,is sole owner of the fields and has entered intoproduction-sharing agreements with major western oilcompanies, led by Chevron and Total. Sonangol recentlycreated a separate joint venture with China’s Sinopecto operate a deep-water field and invested in Gabonwith Ireland’s Tullow Oil. The decision was also made,allegedly owing to political tension with France, notto renew a concession to Total and instead to transferthe licence to a Chinese-led consortium. In an effortto increase local participation in the industry, thegovernment is in the process of introducing newprocurement and employment clauses in theproduction-sharing agreements, and is also consideringa policy to promote local oil companies. Foreigninvestors, which have already resisted a previous proposalto route all industry payments through the domesticfinancial system, are now opposing these moves,claiming that the Angolan business community lacksthe necessary skills.

Diamond mining is the second-largest source ofexport revenues (about 6 per cent of total exports),with 2005 output equal to $892.7 million. It isdifficult to estimate the increase in real production,as a larger share of informal mining has recently beenincluded in official statistics. There are extensivekimberlite and alluvial projects, the latter both formaland informal. In 2005, De Beers re-entered Angolathrough an agreement with state-owned EmpresaNacional de Diamantes de Angola (Endiama), inwhich it will hold a 49 per cent stake, to explore a3 000 sq km kimberlite concession. In November2005, the first polishing and cutting factory wasopened in Luanda, capable of processing $20 millionworth of diamonds per month. Diamond mining isexpected to increase in the short term, as aconsequence of the 296 licences granted in 2004 and2005. Oil, diamond and other mining projectstogether employ an estimated 20 000 people.

1. PSIs are designed to address the needs of low-income members that may not need IMF financial assistance, but seek Fund endorsement

and assessment of their economic policies.

African Economic Outlook© AfDB/OECD 2006

109

Angola

The year 2005 saw a long-delayed recovery of thedomestic non-mining economy, which has finallyexceeded the level prevailing in the early 1990s. Despitethe presence of land mines and devastated infrastructure,which continue to restrict the availability of seeds andfertilisers and to impede marketing, agriculturalproduction has begun to recover. Improved rainfall, thereturn of refugees to the Planalto rural areas and an

increase of about 9.5 per cent in the area undercultivation in 2004 led to a 17 per cent increase in the2004/05 harvest, including both staples (maize, cassava,sorghum) and export crops such as coffee (of whichAngola was once the world’s fourth-largest producer),sisal, tobacco, cotton, palm, sugar, citrus fruits andsesame. According to the World Food Programme,however, the rise in production is smaller than

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries

Oil and gasDiamonds

Construction

Manufacturing

Other services

Wholesale and retail trade9%

4%

16%

8%

4%5%

54%

Figure 2 - GDP by Sector in 2004 (percentage)

Source: Authors’ estimates based on National Institute of Statistics data.

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

GDP at market prices

Other services

Wholesale and retail trade

Construction

Manufacturing

Diamonds

Oil and gas

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries

Figure 3 - Sectoral Contribution to GDP Growth in 2004 (percentage)

Source: Authors’ estimates based on National Institute of Statistics data.

African Economic Outlook © AfDB/OECD 2006

110

Angola

government estimates, and Angola still suffers from ahuge food deficit of 625 000 tonnes per year, partlyowing to the inefficiencies of the distribution system.As a result, the country has to import three-quartersof its food requirements. The livestock situation sufferedless from the war, as cattle were not decimated, andinvestment from Israel and Russia has begun to supportthe development of this sector.

Manufacturing, a thriving sector before the civil war,is now reduced to light industries such as foodprocessing, beverages and textiles. The sector recorded9 per cent growth in 2005, compared to 13.5 per centin 2004. Firms that are shielded from internationalcompetition by either transport costs or trade barriersare benefiting from the growth, as testified by the

results of cement and beverages producers. Petroleumrefining, on the other hand, is operating well undermaximum capacity, due to bottlenecks in provisioningthe only existing facility. The pace of infrastructurerehabilitation is accelerating, with the emphasis mostlyon roads. This activity, together with a mini-boom inresidential and office buildings in Luanda (includinga few skyscrapers built for oil companies), has sustainedthe construction sector, which expanded by an estimated10 per cent in 2005. In services, the communicationssub-sector grew by 35 per cent in the first half of 2005,reflecting the launch of a second cellular phone operatorand increased traffic volumes, and financial servicesalso developed at a brisk pace, particularly in Luandawhere the number of bank branches more than doubledin 2005.

Table 1 - Demand Composition (percentage of GDP)

Source: : IMF and National Institute of Statistics data; estimates (e) and projections (p) based on authors’ calculations.

1997 2002 2003 2004 2005(e) 2006(p) 2007(p)

Gross capital formation 25.5 13.3 12.8 9.2 6.7 5.7 5.5Public 4.7 7.1 7.7 5.0 3.4 2.8 2.7Private 20.8 6.1 5.1 4.3 3.3 2.9 2.8

Consumption 75.2 74.8 80.6 75.3 57.5 51.9 52.5Public 53.8 36.9 34.0 29.4 22.5 19.9 20.2Private 21.4 37.9 46.7 45.9 35.0 32.0 32.2

External sector -0.7 12.0 6.6 15.5 35.8 42.4 42.0Exports 68.5 77.6 70.2 70.5 74.8 72.5 69.3Imports -69.2 -65.6 -63.7 -55.0 -38.9 -30.1 -27.3

Table 1 provides some detail on the historical structureof final demand, clearly revealing the economy’sdependence on exports and its reliance on imports formost consumer goods. Oil and mineral developmentcontinue to dominate Angola’s economic growthprospects. In 2006 and 2007, mineral exports willimprove the external sector balance, adding furtherstimulus to growth. Import volumes are expected togrow by 12 per cent, in tandem with an increase inprivate investment of 17 per cent in real terms; this newinvestment, almost entirely foreign, is concentrated inminerals. Public investment will also rise by 10 per centin real terms in 2006 and 2007, reflecting povertyalleviation programmes and infrastructure reconstruction.The positive sectoral developments mentioned aboveare also expected to increase household incomes, raising

the rate of growth in private consumption to 9 per centin real terms in both 2006 and 2007.

Macroeconomic Policies

Fiscal Policy

Success in the fight against inflation, whichconsistently exceeded 100 per cent a year throughoutthe civil war, is one of the Angolan authorities’ majorachievements. As illustrated below, inflation fell to18.5 per cent at end 2005. Previous price stabilisationefforts were undermined by large fiscal imbalances andsizeable central bank operating deficits caused by theuse of oil revenues and expensive oil-backed loans from

African Economic Outlook© AfDB/OECD 2006

111

Angola

international commercial banks to finance sustainedexpenditure increases (such as a large army and civilservice payroll, arms purchases and consumer subsidies).Progress in tackling these issues has been slow, althoughthe government has reformed the fiscal accounts toreflect reality more accurately than in the past. Theseaccounts now include most off-budget expenditures,including transfers to the military, the quasi-fiscaloperations carried out by Sonangol on behalf of thegovernment and the central bank’s operating deficit.Moreover, the government has made considerableprogress in consolidating and unifying the reportingof government revenue and expenditure.

In 2004, the fiscal deficit fell to 1.5 per cent of GDPas a result of tighter control of current expenditure,higher oil revenues and measures to improve budget

execution procedures. Efforts to contain and monitorexpenditure continued in 2005, notably through thephasing out of price subsidies on petrol (from 3.8 percent of GDP in 2004 to 0.8 per cent in 2005) and publicutilities. Increased oil production combined with highworld oil prices resulted in a 7.9 per cent surplus in 2005.Substantial surpluses are expected in 2006 and 2007as well.

The 2006 draft budget gave higher priority totransport infrastructure, with allocations increasing by10 per cent in real terms to reach 10 per cent of totaloutlays. Infrastructure rehabilitation will be financedwith oil-backed credit lines provided by foreign partnerssuch as China, Brazil, Portugal and Spain. Defenceand security spending is expected to consume 12 percent of total receipts in 2006, down from 17.9 per

Table 2 - Public Finances (percentage of GDP)

a. Only major items are reported.Source: IMF and Ministry of Finance data; estimates (e) and projections (p) based on authors’ calculations.

1997 2002 2003 2004 2005(e) 2006(p) 2007(p)

Total revenue and grantsa 39.6 40.5 38.3 37.4 38.5 37.3 35.8Tax revenue 4.9 8.0 7.8 6.9 5.6 5.0 4.9Oil revenue 33.9 32.5 29.7 30.1 32.6 32.0 30.7

Total expenditure and net lendinga 55.0 49.7 45.7 38.9 31.0 26.7 26.9Current expenditure 51.1 36.9 37.3 31.8 25.1 22.7 23.5

Excluding interest 45.4 33.6 34.8 29.5 23.0 20.9 21.8Wages and salaries 9.6 11.3 12.5 10.5 7.8 6.7 6.6

Interest 5.7 3.3 2.4 2.4 2.1 1.8 1.7Capital expenditure 4.6 7.1 7.4 4.5 3.1 2.6 2.5

Primary balance -9.6 -6.0 -4.9 0.9 9.5 12.4 10.6Overall balance -15.4 -9.3 -7.4 -1.5 7.5 10.6 8.9

cent in 2005. The shares of the 2006 budget allocatedto health and education, however, have been reducedto 4.4 and 3.8 per cent respectively, from 4.9 and7.1 per cent in 2005. In response to donors’ concernsregarding these low allocations to the social sectors, theauthorities argue that the limited absorption capacityof these sectors, and in particular their shortage ofhuman resources, militate against increasing resources.

Monetary Policy

Since September 2003, the rapid accumulation offoreign exchange earnings has allowed the government

to intervene through open-market operations, stabilisethe kwanza’s nominal exchange rate against the dollarand dampen inflationary pressures. Year-on-yearconsumer price index inflation fell to 18.5 per cent inDecember 2005, from 31 per cent one year earlier,despite a 40 per cent increase in the retail price ofpetroleum products. Inflation averaged 22 per cent in2005 and is expected to average 20 per cent and 16 percent in 2006 and 2007 respectively.

The improvement in fiscal outcomes thus far hasbeen due to increases in oil revenue. The governmentcontinues to undertake substantial expenditure that

African Economic Outlook © AfDB/OECD 2006

112

Angola

injects large amounts of kwanzas into the economyand threatens to spark inflation, although spendingon domestically produced goods and services has fallenin real terms, obliging the Banco Nacional de Angolato slow money creation by purchasing kwanzas withdollars derived either from oil receipts or from loansbacked by promises of future oil receipts. The gross costof such measures (that is, excluding the gains obtainedby maintaining low inflation) is estimated to amountto more than $2 billion a year. Moreover, exchange rate-based stabilisation policies entail additional costs suchas currency appreciation, which detracts from thecompetitiveness of domestically produced tradeablegoods. It should be noted, however, that the domesticeconomy consists mostly of non-tradeable services.Furthermore, all these costs must be weighed againstthe fiscal benefits, in terms of improved tax collection,brought about by the decline in inflation. Finally,despite some improvements, a great deal more progressis needed to achieve transparency concerning oilrevenues. Angola has subscribed to the ExtractiveIndustry Transparency Initiative, but de factoimplementation has been limited.

External Position

Angola eliminated export tariffs in 1999, and averageimport duties declined from 17 to 14 per cent between2002 and 2004. A new customs law is being drafted,but no date has been scheduled for its implementation.Angola formally acceded to the Southern AfricanDevelopment Community (SADC) Trade Protocol inMarch 2003 and is currently preparing a schedule forits implementation. The bulk of SADC tradeliberalisation measures are scheduled to be introducedby 2008, and member states are carrying out a mid-term review of the Trade Protocol to that effect – aprocess in which Angola is expected to play an importantrole as a member of the steering committee.

Angola has been the leading beneficiary of theGeneralised System of Preferences (GSP) with theUnited States since 1999 and became eligible to benefitfrom the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA)in December 2003. Angola’s exports under AGOA andits GSP provisions in 2004 – almost entirely oil and

energy products – were valued at $4.3 billion,representing 96 per cent of the country’s total exportsto the United States.

High oil prices coupled with increased productionboosted exports in 2004, resulting in a $7.6 billiontrade surplus. Oil and diamond exports are estimatedto have risen by 65 and 24 per cent respectively overthe 2002-04 period. In 2004, the United States was thelargest export destination (31 per cent), followed byChina at 30 per cent. During the 2000-03 period, thesetwo countries accounted respectively for 41 and 17 percent of total exports. European Union countries are thesingle largest source of imports, accounting for roughlyhalf of Angola’s external purchases. Processed and freshfood products are mostly imported from Portugal andSouth Africa respectively, while the main import itemfrom the United States is equipment and machinery.

Angola recorded its first-ever current account surplusin 2004 (3.5 per cent of GDP), as the trade surplus morethan offset the traditional services account deficit. Thelatter reflects the high levels of services imports requiredby the oil industry. The large deficit in the factor incomeaccount corresponds mainly to remittances of profits.

Exports rose sharply in 2005 to $17.3 million,from $13.4 million in 2004, as a result of rising oilproduction and prices and of increased diamondproduction. Continuing growth in crude oil productionis expected to enhance export volumes further overthe projection period, by an estimated 30 per cent inreal terms in 2006 and 2007. This growth should leadin turn to an increase in imports of capital goods,which are projected to grow by 13 per cent per year inreal terms in 2006 and 2007.

The further increase in international oil prices ismaking deep-water exploration in the South Atlanticfinancially viable, to the point where the world’s mostadvanced technologies are being used in Angola first.The country was Africa’s largest recipient of foreigndirect investment (FDI) flows in 2003 and the second-largest after Nigeria in 2004. New licences for 23 blockswere advertised in the international financial press inNovember 2005.

African Economic Outlook© AfDB/OECD 2006

113

Angola

The rest of the economy attracts little FDI, but theamount is growing. Services, in particular, are viewedas having strong growth potential, as shown by newprojects financed by the Portuguese banks BancoInternacional de Crédito (BIC) and Banco ComercialPortugues (BCP Millennium) and by other investorsin retail trade, telecommunications (Telecom Namibiais to launch the first private fixed-line telephonenetwork), electricity and construction. Belgian andSwiss food companies have invested to expand theiroperations. Investors from Brazil, South Africa andother countries are also thought to be exploring businessopportunities in fertilisers and breweries.

The burden of external debt has eased in recent years.At end-2004, according to IMF and World Bankestimates, Angola’s debt amounted to $8.9 billionincluding arrears and overdue interest, the equivalentof 65.9 per cent of GNI, down from 86.8 per cent in2003. Reliance on costly short-term oil-backed loansis also declining thanks to $2 billion worth of officialcredit lines from China and others. As new financialsources emerge, Angola is now less dependent ontraditional ones such as the OECD countries and theIMF. Moreover, it has restructured its official bilateraldebt obligations with several of its major creditors ina series of bilateral negotiations. Although these trade

Table 3 - Current Account (percentage of GDP)

Source: IMF and National Bank of Angola data; estimates (e) and projections (p) based on authors’ calculations.

1997 2002 2003 2004 2005(e) 2006(p) 2007(p)

Trade balance 31.4 40.8 29.1 39.1 52.4 55.4 54.0Exports of goods (f.o.b.) 65.2 75.7 68.8 69.0 73.8 71.9 68.9Imports of goods (f.o.b.) -33.8 -34.8 -39.6 -29.9 -21.4 -16.5 -14.9

Services -32.1 -28.9 -22.6 -22.9Factor income -12.0 -15.1 -12.5 -12.7Current transfers 1.2 0.3 0.7 0.0

Current account balance -11.5 -2.9 -5.2 3.5

0

50

100

150

200

250

20042003200220012000199919981997

■ Debt/GNI Service/X

Figure 4 - Stock of Total External Debt (percentage of GNI)and Debt Service (percentage of exports of goods and services)

Source: IMF and World Bank.

African Economic Outlook © AfDB/OECD 2006

114

Angola

credit lines carry a higher cost than official multilateralfinance, the authorities are unwilling to weaken theiroperational autonomy, commit firmly to a range ofstructural reforms and reduce their current reliance onselling foreign exchange to contain inflation. At thisstage, a likely compromise is the signing of a home-grown PSI programme that takes into account someof the IMF recommendations.

Structural Issues

Recent Developments

Angola has significantly improved itsmacroeconomic management since the end of the civilwar in 2002. Structural reform should build on thismomentum: in the event that efforts to diminish thecountry’s reliance on oil and diamonds fail, Angolawill soon face an abrupt deceleration of growth, sinceoil production is expected to reach a ceiling in 2008.

Unfortunately, new measures2 to deregulateeconomic activity, sustain the privatisation process andattract foreign investment in the non-oil sectors havebeen slow to produce results. Private investors complainthat risk-taking and job-creating activities are jeopardisedby widespread corruption, outdated regulations andrent-seeking behaviour – an assessment that is confirmedby international rankings such as Doing Business andthe Transparency International index. The domesticbusiness sector includes a small number of businessesthought to have strong political influence (the so-calledempresarios de confiança), and barriers to entry are high.The authorities have begun to address this issue throughefforts to improve the tendering and auditing of publicsector procurement contracts, among other things byemploying new staff at the Accounts Tribunal. In thecase of land reform, major problems remain: mostcolonial registries have been destroyed, and registrationof transfers of ownership, occupation and concessionsis in disarray as ministerial jurisdictions are badly

defined and often overlapping. Decentralisation, whichwas supposed to accelerate the implementation of suchreforms, is incomplete: in practice, it has meantdecentralisation of administrative tasks but notdelegation of spending or taxation authority.

In 2005, structural reforms largely stalled. In thecase of the oil sector, a new bill was presented to theNational Assembly in mid-2005, dealing inter aliawith the handling of foreign currency proceeds fromexports. Foreign investors had claimed that nationalbanks were not prepared to accommodate massiveforeign currency flows efficiently and managed toremove from the law a controversial provision thatrequired oil companies to route their export revenuesthrough domestic rather than international banks.

A competition bill has been drafted, but has notyet been transmitted to parliament. Concerns regardingthe status and success of the privatisation process ledthe authorities to suspend it in 2001. To reactivate thisprocess, the authorities intend to create an independentagency and to establish a legal framework for settingup a stock exchange.

Some state-owned enterprises, such as AngolaTelecom, the railways and the national airline TAAG,have engaged in corporate restructuring with a view toattracting FDI, but improvements in service delivery andfinancial viability have yet to materialise. TAAG, inparticular, has been in debt for years and has periodicallybeen suspended from the International Air TransportAssociation (IATA), although in 2004 it presentedcertified accounts for the first time. The state-owneddiamond company, Endiama, currently combinesregulatory responsibilities with commercial operations,and these two functions should be separated. This is anecessary condition for opening up the diamond sectorto small and medium-scale private operators.

Two of the longest-lasting legacies of the civil warand successive bouts of high inflation have been the

2. These include a new investment law that provides for equal treatment of foreign and Angolan firms (with few exceptions); the new commercial

code enacted in early 2004; the establishment of a national private investment agency (ANIP), a one-stop registration office for companies;

and a land tenure law passed in 2004 with the aim of clarifying property rights and customary tenure.

African Economic Outlook© AfDB/OECD 2006

115

Angola

dollarisation of the economy and the reluctance ofhouseholds to place their savings in formal financialinstitutions. With the return of price stability, the entryof new banks, the opening of a substantial number ofnew branches including in the provinces, and theavailability of withdrawal facilities, total banking depositsincreased by 13.5 per cent in real terms in the first halfof 2005. Access to credit remains severely restricted,however, especially for smaller firms, as banks investin treasury and central bank instruments and have todate shown little inclination to compete for privatesector borrowing. A major achievement was a$200 million syndicated loan negotiated by TAAG inJuly 2005 with three local banks, led by the BancoAfricano de Investimentos and including the BancoEspírito Santo Angola and Banco Comercial Angolano,to finance the purchase of new aircraft. The governmentwill repay the banks with special Treasury notes.

In 2000, the authorities set up a credit institution(Fundo de Desenvolvimento Economico e Social – FDES)to channel part of the country’s large oil revenues tosupport investment in the private sector. According tothe original plan, FDES was supposed to receive$150 million from oil “bonuses” in 2000, but as of mid-2004, only $30 million had been disbursed. A newdevelopment bank, partly modelled on Latin Americanexperiences, will be created in 2006.

Energy infrastructure has not kept pace with thedynamism of the economy, especially in Luanda. Thefrequency of brownouts and power cuts has increased,owing to inefficiencies in thermal generation facilitiesand delays in completing the Capanda dam andhydroelectric plant. This four-turbine plant has beenoperating on an experimental basis since January 2004,when the first 130 MW turbine came on line; this wasfollowed by a second one later the same year. Currently,the power transmission lines are connected toCambambe dam, located in northern Kwanza-NorteProvince. The government approved a $113 million loansecured by Russia Unified Bank that, along with another$130 million from Brazil, will be used for the second

stage of the project, which is scheduled to be completedin 2007.

Transport Infrastructure

The war left a legacy of destruction, mainly in ruralareas, as well as years of neglect and lack of maintenancein Luanda. According to a recent survey on transportconditions in the central highlands, 82 per cent ofcommunities are connected to the road network, buteach year 31 per cent of them remain isolated for atleast five months. The road network is the least densein the northern part of the highlands. In villages wherethere are no roads, the average distance to the nearestroad is five km. The still extensive presence of minesis also a major constraint on mobility, as publictransportation is available to only half of communities(59 per cent of communities during the dry season,47 per cent during the rains).

The task of rehabilitating and expanding transportinfrastructure is enormous. The government initiallyfocused on emergency measures and is now graduallyshifting towards a medium-term multi-modal strategycomprising three interrelated strands:

• the rehabilitation of 457 km of national primaryand secondary roads and the construction of fivemetal bridges;

• rehabilitation of the three main rail corridorsdating from the colonial era, mostly financed bya loan from China (see box). At a later stage, newrailway lines may be constructed linking Angolato the Namibian and Zambian networks. Bysupporting trade relations with South Africa andoffering easier Atlantic access to the ZambianCopperbelt, these rail links could have significanteffects on regional trade, facilitate the resettlementof internally displaced persons and consolidate therecovery of the agricultural sector;

• continued efforts to expand capacity at the portof Luanda3. In August 2005, state-ownedUnicargas began operating a new general-purposeport terminal with capacity to handle

3. The port reportedly received 2 645 commercial ships in 2004, of which 1 925 were on cabotage (local) missions and 739 on long-haul

missions. The port handled 3.19 million tonnes of cargo during the year, 122 000 tonnes more than in 2003.

African Economic Outlook © AfDB/OECD 2006

116

Angola

244 000 tonnes of general cargo a year, under a20-year concession agreement.

Lastly, air travel played a predominant role duringthe war because of military insecurity in the countryside.The country has 13 airports, all of which are in needof rehabilitation. The national privatisation agencyANIP set a target of $250 million in funding for thispurpose in 2002. Projects at Luanda InternationalAirport, which are being undertaken by G.M.International in a joint venture with Sarroch GranulatiSrl, are focused mainly on rehabilitating the runway.An amount of 2.7 million has been allocated for thisproject. There are also plans to develop a new airport

30 km north of Luanda, to be built by Chinesecontractors. Other major airports, at Cabinda, Huamboand Bié, are also being rehabilitated.

With the exception of a toll bridge over the Kwanzariver, authorities have been reluctant to introduce cost-recovery mechanisms for two main reasons. First,transport infrastructure is seen as a crucial instrumentfor post-war nation building, with large and positivenet economic and social externalities that thegovernment is willing to subsidise. Second, in order forproviders to charge for improved roads, users must beprovided with free-of-charge alternatives, the cost ofwhich would far exceed current budget allocations.

China’s Loan to Rehabilitate Transport Infrastructure

Angola has seen a dramatic expansion of its relations with China since early 2005, when China Eximbankextended Angola $2 billion worth of loans to rehabilitate roads and railways, especially in Benguela, whichis critical to mineral exports. China also accounts for a rapidly growing share of oil exports, and Chinesecompanies are taking up old oil licences vacated by a French oil company, Total, whose reputation has beendamaged by the ongoing judicial inquiry in France. Chinese companies are rapidly establishing themselvesin the Angolan construction, telecommunications, power and mining sectors.

The conditions include repayment over 17 years, a period of grace of up to five years, and a 1.5 per centinterest rate per annum. This credit has some advantages and disadvantages for Angola. First, the real costof this loan is higher than that implied by the published rates, because non-Chinese suppliers are excluded,negatively affecting the prices of imports of goods and services. However, this real cost should still be clearlyunder the rates at which Angola was already borrowing elsewhere. Second, Angola has urgent and large needsof financing to support a rapid programme of investments for the recovery of the infrastructure, which wouldallow the reintegration of the country, a basic condition for the reactivation of the economy and, especiallyof the agriculture. This was seen as basic condition for the consolidation of peace and the alleviation of thecatastrophic social problems left by many years of war and economic mismanagement. Other sources offinancing were blocked by Paris Club rules, by the inability to reach an agreement with the IMF.

The project, funded by Chinese loans, involves not only the rehabilitation of the three main lines – the1 336-km Benguela railway from Lobito to the eastern border with Zambia and the Democratic Republicof Congo, the 479-km Caminho de Ferro de Luanda from Luanda to Malanje and the 907-km Moçamedesrailway inland from the coastal town of Namibe – but also construction of several transversal sectionslinking the three existing east-west lines. According to the transport minister, André Luís Brandão, the Namibeand Benguela lines should be operational within three years. Having already rehabilitated 17 de SetiembroAirport, the Chinese government will also finance the construction of a new airport in the central Benguelaprovince.

African Economic Outlook© AfDB/OECD 2006

117

Angola

Political and Social Context

Thirty years after Angola won independence and fouryears after a cease-fire was signed between the armedforces and the rebels on 4 April 2002, the presidentialelections – initially scheduled for September 2006 andeventually set for the first quarter of 2007 – will constitutea milestone in national reconciliation and theconsolidation of democratic institutions. Parliamenthas passed the legislation necessary for carrying out theelections, which includes establishing a national electoralcommission (CNE), preparing the voter registry andallowing the President to serve three consecutive termsof office. Opinions differ as to the importance of delayingthe process. While this may be seen as a dilatory tacticon the part of the Movimento Popular de Libertaçãode Angola (MPLA), holding the vote in a context ofdistrust among political parties could be detrimental tothe consolidation of peace. No opinion polls exist inAngola, but the MPLA seems guaranteed to remain inpower owing to the weakness of, and divisions in, theopposition parties, the dominance that the ruling partyexercises over state resources and the CNE, and thefeebleness of civil society, including the press. Althoughpeace seems to be firmly established, the continuingarmed conflict in Cabinda, albeit of low intensity,remains a cause of concern in view of the strategicimportance of the enclave for oil exploration.

According to a World Food Programme survey, themajority of household members (67 per cent) havebeen displaced at least once during their lifetimes, andthe average period of displacement is 5.4 years. In2005, the government reported that 2.34 millioninternally displaced people, out of the 4.1 millionestimated at the end of the hostilities, had returned totheir areas of origin, primarily in the provinces ofHuambo, Benguela, Kwanza Sul and Bié. In addition,approximately half of the estimated 450 000 refugeesto neighbouring countries had returned home since2002. The average period since their return (as ofDecember 2004) is just over three years, allowinghouseholds two or three harvests. The last importantwave of resettlement in the Planalto took place in2002/03, when 47 per cent of the total displacedpopulation returned home.

Major social indicators such as life expectancy,malnutrition and access to water and sanitationdeteriorated sharply during the war and are still atalarming levels. The rate of maternal mortality is oneof the highest in the world: 1 800 per 100 000 births,compared to a Southern African DevelopmentCommunity (SADC) average of 560. Angola has theworld’s third-highest under-five child mortality rate, with250 deaths per 1 000 children, owing to malaria,respiratory infections, diarrhoea, measles and neo-nataltetanus; the SADC average is 137. Malnutrition is animportant underlying condition, estimated to affectalmost half of Angola’s 7.4 million children.

The majority of the population does not have accessto health care. Despite recent efforts to increase theavailability of health facilities, expenditure is still verylow. Owing to the effects of the civil war and theinsignificant resources allocated to the health sectorover more than two decades, indicators of healthoutcomes will take considerable time to showimprovement. In the central highlands only 13 percent of the communities have a hospital or health post;the average distance to the nearest health facility ismore than 20 km; and 60 per cent of communities relyon unqualified health providers, such as traditionalmidwives, while only one-third of the health facilitiesin the area are staffed with qualified health professionals.

The underlying causes of the low rate of access tohealth services and the poor quality of those servicesare the huge human capital deficit – there is only onephysician for every 13 000 people – and the very lowquality of social spending. The funds allocated to thehealth sector are fragmented into distinct budgetaryunits at provincial level and dispersed in a large numberof sub-sectoral policies, programmes and plans withouta sector-wide plan of action.

Faced with these enormous social challenges, thegovernment expressed its resolve to launch a series ofaction plans. Although the finalisation of Angola’s firstPoverty Reduction Strategy Paper, released in draftform in early 2004, has been delayed, the governmenthas launched a general programme for 2005/06 tomobilise action in priority areas, including food security

African Economic Outlook © AfDB/OECD 2006

118

Angola

and rural development, mine clearance andinfrastructure rehabilitation. At the same time, donorsare currently shifting from emergency intervention toa developmental approach, focusing their initiativeson achieving the MDGs and fostering democraticgovernance. In this context, donors are pressing theauthorities to step up the fight against corruption andimprove transparency in the use of oil revenues.

Largely owing to the population’s lack of mobilityduring the war, HIV prevalence in Angola isconsiderably lower than in neighbouring countries. AUNICEF survey, which covered some 12 000 womentested at pre-natal clinics in all 18 provinces, found thatonly 2.8 per cent of them were infected, which wouldimply an overall adult HIV infection rate of about5 per cent. However, the results of a more recentnational survey have raised doubts regarding thereliability of the earlier data, which may seriously haveunderestimated the magnitude of the problem. Therecent study shows that HIV prevalence is significantlyhigher in border provinces, suggesting that populationmovements have been accelerating the rate at which theinfection is spreading across borders and along majorcorridors. In Cunene province, at the border withNamibia, the prevalence rate is as high as 9.1 per cent.

The perception of a relatively low prevalence ofHIV led to a lag in medical response and extremely lowbudgetary allocations over the past three years. Althoughthe government has established a National AIDSCommission and approved a National Strategic Plan(estimated at $92 million for five years and financedby the United Nations), progress in establishingprevention and treatment measures has been slow.Most activities related to preventive education and themitigation of discriminatory practices are still in theearly stages and depend mainly on the efforts of non-governmental organisations and the international donorcommunity. Currently, awareness of preventive measuresis very low. For instance, only 17 per cent of thepopulation could correctly identify three ways ofavoiding HIV infection. In addition, there are fewtesting and treatment facilities, especially in theprovinces, reflecting a low level of commitment bymany local authorities. In 2004, the government opened

the first day hospital in Luanda to provide specialisedcare and has subsidised antiretroviral (ARV) therapy for2 000 patients, out of an estimated 40 000 people inneed of ARV treatment. Clearly, Angola still faces anumber of major challenges: expanding treatmentfacilities in Luanda and priority provinces, providingtraining for personnel, supplying tests and othermaterials, and improving monitoring, with particularemphasis on the most affected areas, border regions andpotential transmission corridors.

According to a rural household survey carried outin 2005, the illiteracy rate among heads of householdis 60 per cent, and of those who are literate, 73 per centnever completed primary education. The war hascompounded the lack of school infrastructure andpersonnel, which is exacerbated in rural areas. Currently,according to national sources the primary schoolenrolment rate is 115 per cent, indicating that manychildren above 10 years of age attend primary school.The combined primary and secondary school enrolmentrate of children aged 5 to 18 years is 63 per cent, butonly 5 per cent of the 10-18 age group is enrolled insecondary school. The performance of the educationalsystem is weakened by children’s late age at the timeof enrolment, high repetition and dropout rates, thevery poor quality of facilities and the irregularity withwhich classes are held.

To address these challenges, the Ministry ofEducation has reformulated the Plano-Quadro deReconstrução do Sistema Educativo, setting new targetsto be achieved by 2015. The challenges remainenormous. In order to achieve universal primaryenrolment and completion rates while keeping pace withthe rapid growth of the school-age population, thenumber of pupils enrolled in primary school needs togrow from an estimated 1.2 million in 2002 to 5 millionby 2015. In addition, in order to improve the availabilityand quality of primary education, large numbers ofadditional well-trained teachers are needed. To thatend, the Ministry of Education with the assistance ofUNICEF has recently drawn up a national capacity-building plan that aims to improve the teaching skillsof some of the 29 000 teachers recruited in 2003.