Andi Fink - Project Five

Transcript of Andi Fink - Project Five

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

1/27

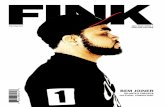

Project5|Magazine

Project:

Youwilldevelopanewmagazinebasedonatopicandaudiencethatwillbegiventoyourandomly.Afterdeterminingallofthecontentandovealldirectionofthe

magazineyouwillproduceaminimumofthreedifferentgridstructuresforthe

design.Onceoneisselectedyouwillbeginwithroughdesigns.Oncethesearecompleteyouwillbeproducingonetight,colorprototupeofacompletemagazine.

Thesepiecewillbemountedonblackboard.

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

2/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

3/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

4/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

5/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

6/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

7/27

Andy Warhol is an art-world colossus whowork accounts for one sixth of contempor

art sales. How did that happen, and is he

really worth it? Bryan Appleyard canvasse

the experts.

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

8/27

Te market backs the enthusiasm o the young. Toseoriginal soup cans are not or sale: bought by the Los An-geles dealer or $1,000, they were sold to the Museum oModern Art in New York in 1996 or $15m, a deal that pro-moted Warhol to arts rst division. In 2008 a 12-oot-wideWarhol painting entitled Eight Elvises, made in 1963,broke the $100m barrier, putting him in the same loybracket as Picasso, Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Gus-tav Klimt. Te highest auction price, meanwhile, is $71.7mor Green Car Crash (1963). o put these dizzying pricesin perspective, itian recently achieved his highest everauction price$16.9m or A Sacra Conversazione romabout 1560. Tis is an important picture by an artist manyregard as the greatest painter that ever lived. But the mar-ket says that Warhol is more than ve times better.

Warhol is now the god o contemporary art. He is indeed,it is said, the American Picasso or, i you preer, the artmarkets one-man Dow Jones. In 2010 his work sold or atotal o $313m and accounted or 17% o all contemporaryauction sales. Tis was a 229% increase on the previousyearnothing bounced out o recession quite like a War-hol. But perhaps the most signicant gure is the rise in hisaverage auction prices between 1985 and the end o 2010:3,400%. Te contemporary-art market as a whole rose byabout hal that, the Dow by about a h. Warhol is the

backbone o any auction o post-war contemporary art,says Christopher Gaillard, president o the art consultantsGurr Johns. He is the great moneymaker.

Some glee in the market is understandableand not justbecause o the money. Warhol believed in ame and wealth:they were intrinsic to his aesthetic. Te auctioneers are co-creators, carrying on Warhols work post mortem, and thesalerooms are extensions o the galleries. How he wouldlove it all! says Sara Friedlander o the current renzy. Ican see him at an auction, seated at ront and centre withhis Polaroid camera and his right wig I think o him inevery sale we do.

othing good was made in the 19th century,nothing really good was made in the 18thcentury and American art in the 20th centu-ry or the rst three, our or ve decades was

very elitist, says Sara Friedlander, the heado First Open Sale at Chrities in New York.Tere was, in this view, no American i-

tian or Picasso, Raphael or Matisse. And then,suddenly, on July 9th 1962, there was. Tat

was the date o the rst solo show by Andy Warhol, the33-year-old son o Slovakian immigrants. It was at the Fer-us Gallery in Los Angeles and it consisted o a series o 32paintings o Campbells Soup Cans, one or each avourbee, clam chowder, cheddar cheese, etc. Te response wasunderwhelming. Five sold or $100 each, but the galleryowner bought them back to keep the series intact.

Nevertheless, by the end o that year, Warhol had con-quered New York, the capital o the art world, and Americahad the artist or which she had been waiting. He reacheda public, says Friedlander, that no artist was able to do be-ore him. Because he was able to accomplish what nobodyelse had done and in the way he was able to inuence whatcame aer him, I think that makes him, I would guess, thegreatest artist o the 20th century.Tere is nothing unorthodox about this claim. Almost

unanimously, todays young art ans adore Andy as earliergenerations adored Pablo Picasso or Jackson Pollock. othe under-45s, says Georgina Adam o the Art Newspa-per, Warhol is what Picasso used to be to an older gen-erationand, like Picasso, he has become a man or allseasons.

Tis vast an base has been reinorced by the shrewd licens-ing arrangements negotiated by the Andy Warhol Founda-tion or the Visual Arts, established under the terms o theartists will. Tere have been Warhol skateboards, Warholeditions o Dom Prignon champagne and countless War-hol ashion lines, including Pepe jeans and Diane von Fur-stenberg dresses. But, in a wider sense, Warhols coloursand stylesespecially his use o pop stylepervade theculture. Any city street shows evidence o the astonishingpower and durability o his imagery.

Beore Warhol, the believers argue, there was sterility; a-ter Warhol there is a ravishing, visual cornucopia. Withouthim, they say, there would be no Jef Koons, no RichardPrince, no Banksy, no akashi Murakami, no DamienHirst. Many o the ashionable artists in the world emergedrom beneath Andys right wig.

Tere would also be no un without Andy. Te startingpoint or any assessment o his legacy is his instant accessi-bility: nobody need ever be puzzled by a Warholhis lav-ish colours, his epic simplicity, above all his subject matter.Andy always painted amous things, says the artist Mi-chael Craig-Martin, whether it was Liz aylor or a Cokecan. Even children love him, says Gul Coskun, a special-ist Warhol dealer in London. Tey stop their parents out-side my shop. His pictures are big, colourul, they are nottaxing academically. But they are taxing nancially now.

All o which raises the question: is this a bubblecriti-cal and nancialthat will soon burst? In market terms,it seems likely i only because the rise in values has beenso extreme. But the problem is that the market concealsmore than it reveals. Tere are, it is said, 10,000 individualworksthe exact number will only become clear when the

vast catalogue raisonn is completed by the Warhol Foun-dation. Tey have just started work on Volume Four o this

mighty project, but there is no current indication o whenit will be nished.

About 200 Warhols come on the market each year. A largepercentage are always bought by Jos Mugrabi, a NewYork-based dealer-collector who turns up at auctions in

jeans, black -shirt and baseball cap. Mugrabi made hismoney in textiles in Colombia. He moved to New York in1982 and began collecting art. He likes to be seen to bebuying and he is now believed to own 800 Warhols, someo them rst-rank. Last year he is said to have bought morethan 40% o the Warhols that came on the market. Tisscale o participation distorts the market and entails a risko a swi collapse i Mugrabi were to withdraw. Te ques-tion is, says Noah Horowitz, author o Art o the Deal:Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market, what

value would those works sustain i and when the marketsees some sort o correction?

Christopher Gaillard does not think this is a problem.Warhol is a global commodity now. His work is certainlysupported by some key players we read about in the papers,but its my belie that this is much more ar-reaching thanthat. Warhol is the most powerul contemporary-art brandthat exists. Picasso is another. Its about sheer, instant rec-ognition and what comes along with it is a sense o wealth,glamour and power.

Te cans he exhibited in Los Angeles emerged both romhis mothers menu and rom a love o the colourul worldo consumption. So they were not quite as impersonal as isoen claimed. Warhols approach to pop culture, Scher-man and Dalton argue, was ar rom purely aesthetic:rom childhood on, he loved its products and worshippedits heroes and heroines.

But his psychology played no part in their reception: theywere seen as works devoid o introspection, shocking state-ments o the obvious. Whereas innocent viewers couldstand in ront o a Pollock and get no answer to the ques-tion What is it?, they would get an immediate answerstanding in ront o a Warhol. Its a soup can.

It seems, wrote the artist Donald Judd o a 1963 Warholexhibition, that the salient metaphysical question lately is

Why does Andy Warhol paint Campbell Soup cans? Teonly available answer is Why not?

Warhol now endorses a way o lie. One simple technol-ogysilk-screen printingdominated his career. But itwas enough to show todays technology-laden, hyper-con-nected youth that they could do it too. Te Andy WarholFoundation and the market may want him to be Leonardoor Picasso, but the young want him to be the overthrowero all such pretensions. It is in this balance o aspirationsthat Warhol, the god o contemporary art, now exists. Intime this phase will pass and the idea that Warhol is agreater artist than, say, Robert Rauschenberg or JacksonPollock will be seen as the absurdity that it is. Te bubblewill burst, prices will all and the drinker o all that Camp-bells soup will be restored to his rightul placeas a brieybrilliant and very poignant recorder o the dazzling suraceo where we are now.

Warhol was an artist, a generator o meanings. Valerie So-lanas and his own social ambitions put an end to this. Nowit is time or us, and the market, to adjust to the act thatit is over

economist.com APRIL 2012

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

9/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

10/27

Andy Warhold is an art-world colossus whosework accounts for one sixth of contemporary

art sales. How did that happen, and is he re-

ally worth it? Bryan Appleyard canvasses theexperts.

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

11/27

Te market backs the enthusiasm o the young. Toseoriginal soup cans are not or sale: bought by the Los An-geles dealer or $1,000, they were sold to the Museum oModern Art in New York in 1996 or $15m, a deal that pro-moted Warhol to arts rst division. In 2008 a 12-oot-wideWarhol painting entitled Eight Elvises, made in 1963,broke the $100m barrier, putting him in the same loy

bracket as Picasso, Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Gus-tav Klimt. Te highest auction price, meanwhile, is $71.7mor Green Car Crash (1963). o put these dizzy ing pricesin perspective, itian recently achieved his highest everauction price$16.9m or A Sacra Conversazione romabout 1560. Tis is an important picture by an artist manyregard as the greatest painter that ever lived. But the mar-ket says that Warhol is more than ve times better.

Warhol is now the god o contemporary art. He is indeed,it is said, the American Picasso or, i you preer, the artmarkets one-man Dow Jones. In 2010 his work sold or a

total o $313m and accounted or 17% o all contemporaryauction sales. Tis was a 229% increase on the previousyearnothing bounced out o recession quite like a War-hol. But perhaps the most signicant gure is the rise in hisaverage auction prices between 1985 and the end o 2010:3,400%. Te contemporary-art market as a whole rose byabout hal that, the Dow by about a h. Warhol is thebackbone o any auction o post-war contemporary art,says Christopher Gaillard, president o the art consultantsGurr Johns. He is the great moneymaker.

Some glee in the market is understandableand not justbecause o the money. Warhol believed in ame and wealth:they were intrinsic to his aesthetic. Te auctioneers are co-creators, carrying on Warhols work post mortem, and thesalerooms are extensions o the galleries. How he wouldlove it all! says Sara Friedlander o the current renzy. Ican see him at an auction, seated at ront and centre with

his Polaroid camera and his right wig I think o him inevery sale we do.

othing good was made in the 19th century,nothing really good was made in the 18thcentury and American art in the 20th centu-ry or the rst three, our or ve decades wasvery elitist , says Sara Friedlander, the heado First Open Sale at Chrities in New York.Tere was, in this view, no American i-

tian or Picasso, Raphael or Matisse. And then,suddenly, on July 9th 1962, there was. Tat

was the date o the rst solo show by Andy Warhol, the33-year-old son o Slovakian immigrants. It was at the Fer-us Gallery in Los Angeles and it consisted o a series o 32paintings o Campbells Soup Cans, one or each avourbee, clam chowder, cheddar cheese, etc. Te response wasunderwhelming. Five sold or $100 each, but the galleryowner bought them back to keep the series intact.

Nevertheless, by the end o that year, Warhol had con-quered New York, the capital o the art world, and Americahad the artist or which she had been waiting. He reacheda public, says Friedlander, that no artist was able to do be-ore him. Because he was able to accomplish what nobodyelse had done and in the way he was able to inuence whatcame aer him, I think that makes him, I would guess, thegreatest artist o the 20th century.Tere is nothing unorthodox about this claim. Almost

unanimously, todays young art ans adore Andy as earliergenerations adored Pablo Picasso or Jackson Pollock. othe under-45s, says Georgina Adam o the Art Newspa-per, Warhol is what Picasso used to be to an older gen-erationand, like Picasso, he has become a man or allseasons.

Tis vast an base has been reinorced by the shrewd licens-ing arrangements negotiated by the Andy Warhol Founda-tion or the Visual Arts, established under the terms o theartists will. Tere have been Warhol skateboards, Warholeditions o Dom Prignon champagne and countless War-hol ashion lines, including Pepe jeans and Diane von Fur-stenberg dresses. But, in a wider sense, Warhols coloursand stylesespecially his use o pop stylepervade theculture. Any city street shows evidence o the astonishingpower and durability o his imagery.

Beore Warhol, the believers argue, there was steriliter Warhol there is a ravishing, visual cornucopia. Whim, they say, there would be no Jef Koons, no RiPrince, no Banksy, no akashi Murakami, no DaHirst. Many o the ashionable artists in the world emrom beneath Andys right wig.

Tere would also be no un without Andy. Te stapoint or any assessment o his legacy is his instant acbility: nobody need ever be puzzled by a Warholhish colours, his epic simplicity, above all his subject mAndy always painted amous things, says the artischael Craig-Martin, whether it was Liz aylor or acan. Even children love him, says Gul C oskun, a spist Warhol dealer in London. Tey stop their parentside my shop. His pictures are big, colourul, they ataxing academically. But they are taxing nancially n

All o which raises the question: is this a bubblecal and nancialthat will soon burst? In market tit seems likely i only because the rise in values hasso extreme. But the problem is that the market comore than it reveals. Tere are, it is said, 10,000 indivworksthe exact number will only become clear whvast catalogue raisonn is completed by the Warhol dation. Tey have just started work on Volume Four

mighty project, but there is no current indication o it will be nished.

About 200 Warhols come on the market each year. Apercentage are always bought by Jos Mugrabi, aYork-based dealer-collector who turns up at auctiojeans, black -shirt and baseball cap. Mugrabi madmoney in textiles in Colombia. He moved to New Yo1982 and began collecting art. He likes to be seen buying and he is now believed to own 800 Warhols, o them rst-rank. Last year he is said to have boughtthan 40% o the Warhols that came on the marketscale o participation distorts the market and entails o a swi collapse i Mugrabi were to withdraw. Tetion is, says Noah Horowitz, author o Art o theContemporary Art in a Global Financial Market, value would those works sustain i and when the msees some sort o correction?

19 economist.com APRIL 2012

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

12/27

Christopher Gaillard does not think this is a problem.Warhol is a global commodity now. His work is certainlysupported by some key players we read about in the papers,but its my belie that this is much more ar-reaching thanthat. Warhol is the most powerul contemporary-art brandthat exists. Picasso is another. Its about sheer, instant rec-ognition and what comes along with it is a sense o wealth,

glamour and power.

Te cans he exhibited in Los Angeles emerged both romhis mothers menu and rom a love o the colourul worldo consumption. So they were not quite as impersonal as isoen claimed. Warhols approach to pop culture, Scher-man and Dalton argue, was ar rom purely aesthetic:rom childhood on, he loved its products and worshippedits heroes and heroines.

But his psychology played no part in their reception: theywere seen as works devoid o introspection, shocking state-ments o the obvious. Whereas innocent viewers couldstand in ront o a Pollock and get no answer to the ques-tion What is it?, they would get an immediate answerstanding in ront o a Warhol. Its a soup can.

It seems, wrote the artist Donald Judd o a 1963 Warholexhibition, that the salient metaphysical question lately is

Why does Andy Warhol paint Campbell Soup cans? Teonly available answer is Why not?

Warhol now endorses a way o lie. One simple technol-ogysilk-screen printingdominated his career. But itwas enough to show todays technology-laden, hyper-con-nected youth that they could do it too. Te Andy WarholFoundation and the market may want him to be Leonardoor Picasso, but the young want him to be the overthrowero all such pretensions. It is in this balance o aspirationsthat Warhol, the god o contemporary art, now exists. Intime this phase will pass and the idea that Warhol is agreater artist than, say, Robert Rauschenberg or JacksonPollock will be seen as the absurdity that it is. Te bubblewill burst, prices will all and the drinker o all that Camp-bells soup will be restored to his rightul placeas a brieybrilliant and very poignant recorder o the dazzling suraceo where we are now.

Warhol was an artist, a generator o meanings. Valerie So-lanas and his own social ambitions put an end to this. Nowit is time or us, and the market, to adjust to the act thatit is over

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

13/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

14/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

15/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

16/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

17/27

Shortly beore his death, Marlon Brando was working on a series oinstructional videos about acting, to be called Lying or a Living. On thesurviving ootage, Brando can be seen dispensing gnomic advice on hiscra to a group o enthusiastic, i somewhat bemused, Hollywood stars,including Leonardo Di Caprio and Sean Penn. Brando also recruited ran-dom people rom the Los Angeles street and persuaded them to improvise(the ootage is said to include a memorable scene eaturing two dwarvesand a giant Samoan). I you can lie, you can act, Brando told Jod Kaan,a writer or Rolling Stone and one o the ew people to have viewed theootage. Are you good at lying? asked Kaan. Jesus, said Brando, Imabulous at it.

Brando was not the rst person to note that the line between an artist anda liar is a ne one. I art is a kind o lying, then lying is a orm o art, albeito a lower orderas Oscar Wilde and Mark wain have observed. Bothliars and artists reuse to accept the tyranny o reality. Both careully crastories that are worthy o beliea skill requiring intellectual sophistica-tion, emotional sensitivity and physical sel-control (liars are writers andperormers o their own work). Such parallels are hardly coincidental,as I discovered while researching my book on lying. Indeed, lying andartistic storytelling spring rom a common neurological rootone that isexposed in the cases o psychiatric patients who sufer rom a particularkind o impairment.

Humans are natural-born storytellers, so lying is in our blood.IAN LESLIEconsiders how this comes out in our art ...

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

18/27

case study published in 1985 by Antonio Dama-sio, a neurologist, tells the story o a middle-agedwoman with brain damage caused by a series o

strokes. She retained cognitive abilities, includingcoherent speech, but what she actually said wasrather unpredictable. Checking her knowledge

o contemporary events, Damasio asked her about the FalklandsWar.

Tis patient spontaneously described a blissul holiday she hadtaken in the islands, involving long strolls with her husband andthe purchase o local trinkets rom a shop. Asked what languagewas spoken there, she replied, Falklandese. What else?In the language o psychiatry, this woman was conabulat-ing. Chronic conabulation is a rare type o memory problemthat afects a small proportion o brain-damaged people. In theliterature it is dened as the production o abricated, distortedor misinterpreted memories about onesel or the world, withoutthe conscious intention to deceive. Whereas amnesiacs makeerrors o omissionthere are gaps in their recollections they nd

impossible to llconabulators make errors o commission: theymake things up. Rather than orgetting, they are inventing.Conabulating patients are nearly always oblivious to their owncondition, and will earnestly give absurdly implausible expla-nations o why theyre in hospital, or talking to a doctor. Onepatient, asked about his surgical scar, explained that during thesecond world war he surprised a teenage girl who shot him threetimes in the head, killing him, only or surgery to bring him backto lie. Te same patient, when asked about his amily, describedhow at various times they had died in his arms, or had been killedbeore his eyes. Others tell yet more antastical tales, about tripsto the moon, ghting alongside Alexander in India or seeing Jesuson the Cross. C onabulators arent out to deceive. Tey engagein what Morris Moscovitch, a neuropsychologist, calls honestlying. Uncertain, and obscurely distressed by their uncertainty,

they are seized by a compulsion to narrate: a deep-seated needto shape, order and explain what they do not understand.

As with the woman who told o her holiday in the Falklands, stories spun by chronic conabulators are conjured up instan-taneouslyan interlocutor only has to ask a question, or say a

particular word, and theyre of, like a jazz saxophonist using phrase thrown out by his pianist as the start o his solo. A patmight explain to her visiting riend that shes in hospital becashe now works as a psychiatrist, that the man standing next toher (the real doctor) is her assistant, and they are about to vispatient. Chronic conabulators are oen highly inventive at th

verbal level, jamming together words in nonsensical but sug-gestive ways: one patient, when asked what happened to QueMarie Antoinette o France, answered that she had been sui-cided by her amily. In a sense, these patients are like novelisdescribed by Henry James: people on whom nothing is wastUnlike writers, however, they have little or no control over thown material.Chronic conabulation is usually associated with damage to thbrains rontal lobes, particularly the region responsible or seregulation and sel-censoring. O course we all are sensitive to

associationshear the word scar and you too might think awar wounds, old movies or tales o near-death experiences. Brarely do we let these random thoughts reach consciousness, ewer still would ever articulate them. We sel-censor or the o truth, sense and social appropriateness. Chronic conabulacant do this. Tey randomly combine real memories with strthoughts, wishes and hopes, and summon up a story rom thconusion.

Te wider signicance o this condition is what it tells us abouourselves. Evidently there is a gushing river o verbal creativitthe normal human mind, rom which both artistic invention lying are drawn. We are born storytellers, spinning narrative o our experience and imagination, straining against the leashkeeps us tethered to reality. Tis is a wonderul thing; it is whgives us our ability to conceive o alternative utures and dife

worlds. And it helps us to understand our own lives through entertaining stories o others. But it can lead us into trouble, pticularly when we try to persuade others that our inventions real. Most o the time, as our stories bubble up to consciousnwe exercise our cerebral censors, controlling which stories weand to whom. Yet people lie or all sorts o reasons, includingact that conabulating can be dangerously un.

36 economist.com APRIL 2012

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

19/27

During a now-amous libel case in 1996, Jonathan Aitken, aormer cabinet minister, recounted a tale to illustrate the horrorshe endured aer a national newspaper tainted his name. He told

o how, on leaving his home in Westminster one morning with histeenage daughter, he ound himsel stampeded by a documen-tary crew. Upset and scared by the crews aggressive behaviour, hisdaughter burst into tears, he said, and Aitken bundled her into hisministerial car. But as they drove away he realised that they werebeing ollowed by the journalists in their van. A hair-raising chaseacross central London ensued. Te journalists were only shakenof when Aitken executed a cunning deception: he stopped at theSpanish embassy and swapped vehicles.Te case, which stretched on or more than two years, involveda series o claims made by the Guardian about Aitkens relation-ships with Saudi arms dealers, including meetings he allegedlyheld with them on a trip to Paris while he was a government min-ister. What amazed many in hindsight was the sheer superuity othe lies Aitken told during his testimony. Some were necessary tomaintain his original lie, but others were told, it appeared, or the

sheer thrill o invention. As Aitken stood at the witness stand andpiled lie upon lieapparently carried away by the improvisatoryact o creativityits possible that he elt similar to Brando duringone o his perormances. Aitkens case collapsed in June 1997,when the deence nally ound indisputable evidence about hisParis trip. Until then, Aitkens charm, uency and air or theatri-cal displays o sincerity looked as i they might bring him victory.Te rst big dent in his aade came just days beore, when adocumentary crew submitted the unedited rushes o their stam-pede encounter with Aitken outside his home. Tey revealed thatnot only was Aitkens daughter not with him that day (when hewas indeed doorstepped), but also that the minister had simplygot into his car and drove of, with no vehicle in pursuit.

O course, unlike Aitken, actors, playwrights and novelists arenot literally attempting to deceive us, because the rules are laid

out in advance: come to the theatre, or open this book, and welllie to you. Perhaps this is why we elt it necessary to invent art inthe rst place: as a sae space into which our lies can be corralled,and channelled into something socially useul. Te key way inwhich artistic lies difer rom normal lies, and rom the honestlying o chronic conabulators, is that they have a meaning andresonance beyond their creator. Te liar lies on behal o himsel;the artist tell l ies on behal o everyone. I writers have a compul-sion to narrate, they compel themselves to nd insights aboutthe human condition. Mario Vargas Llosa has wr itten that novelsexpress a curious truth that can only be expressed in a urt iveand veiled ashion, masquerading as what it is not. Art is a liewhose secret ingredient is truth

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

20/27

Shortly beore his death, Marlon Brando was working on a series oinstructional videos about acting, to be called Lying or a Living. On thesurviving ootage, Brando can be seen dispensing gnomic advice on hiscra to a group o enthusiastic, i somewhat bemused, Hollywood stars,including Leonardo Di Caprio and Sean Penn. Brando also recruited ran-dom people rom the Los Angeles street and persuaded them to improvise(the ootage is said to include a memorable scene eaturing two dwarvesand a giant Samoan). I you can lie, you can act, Brando told Jod Kaan,a writer or Rolling Stone and one o the ew people to have viewed theootage. Are you good at lying? asked Kaan. Jesus, said Brando, Imabulous at it.

Brando was not the rst person to note that the line between an artist anda liar is a ne one. I art is a kind o lying, then lying is a orm o art, albeito a lower orderas Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain have observed. Bothliars and artists reuse to accept the tyranny o reality. Both careully crastories that are worthy o beliea skill requiring intellectual sophistica-tion, emotional sensitivity and physical sel-control (liars are writers andperormers o their own work). Such parallels are hardly coincidental,as I discovered while researching my book on lying. Indeed, lying andartistic storytelling spring rom a common neurological rootone that isexposed in the cases o psychiatric patients who sufer rom a particularkind o impairment.

Humans are natural-born storytellers, so lying is in our blood.IAN LESLIEconsiders how this comes out in our art ...

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

21/27

case study published in 1985 by Antonio Dama-sio, a neurologist, tells the story o a middle-agedwoman with brain damage caused by a series

o strokes. She retained cognitive abilities, including coherentspeech, but what she actually said was rather unpredictable.Checking her knowledge o contemporary events, Damasio askedher about the Falklands War.Tis patient spontaneously described a blissul holiday she had

taken in the islands, involving long strolls with her husband andthe purchase o local trinkets rom a shop. Asked what languagewas spoken there, she replied, Falklandese. What else?In the language o psychiatry, this woman was conabulat-ing. Chronic conabulation is a rare type o memory problemthat aects a small proportion o brain-damaged people. In theliterature it is dened as the production o abricated, distortedor misinterpreted memories about onesel or the world, withoutthe conscious intention to deceive. Whereas amnesiacs makeerrors o omissionthere are gaps in their recollections they ndimpossible to llconabulators make errors o commission: theymake things up. Rather than orgetting, they are inventing.Conabulating patients are nearly always oblivious to their owncondition, and will earnestly give absurdly implausible expla-nations o why theyre in hospital, or talking to a doctor. Onepatient, asked about his surgical scar, explained that during thesecond world war he surprised a teenage girl who shot him threetimes in the head, killing him, only or surgery to bring him backto lie. Te same patient, when asked about his amily, describedhow at various times they had died in his arms, or had been kille dbeore his eyes. Others tell yet more antastical tales, about tripsto the moon, ghting alongside Alexander in India or seeing Jesuson the Cross. Conabulators arent out to deceive. Tey engagein what Morris Moscovitch, a neuropsychologist, calls honestlying. Uncertain, and obscurely distressed by their uncertainty,they are seized by a compulsion to narrate: a deep-seated needto shape, order and explain what they do not understand.

As with the woman who told o her holiday in the Falklands, thestories spun by chronic conabulators are conjured up instan-taneouslyan interlocutor only has to ask a question, or say aparticular word, and theyre o, like a jazz saxophonist using aphrase thrown out by his pianist as the start o his solo. A patientmight explain to her visiting riend that shes in hospital becauseshe now works as a psychiatrist, that the man standing next toher (the real doctor) is her assistant, and they are about to visit apatient. Chronic conabulators are oen highly inventive at the

verbal level, jamming together words in nonsensical but sug-gestive ways: one patient, when asked what happened to QueenMarie Antoinette o France, answered that she had been sui-cided by her amily. In a sense, these patients are like novelists, asdescribed by Henry James: people on whom nothing is wasted.Unlike writers, however, they have little or no control over theirown material.

Chronic conabulation is usually associated with damage to thebrains rontal lobes, particularly the region responsible or sel-regulation and sel-censoring. O course we all are sensitive toassociationshear the word scar and you too might think aboutwar wounds, old movies or tales o near-death experiences. Butrarely do we let these random thoughts reach consciousness, andewer still would ever articulate them. We sel-censor or the sakeo truth, sense and social appropriateness. Chronic conabulatorscant do this. Tey randomly combine real memories with straythoughts, wishes and hopes, and summon up a story rom theconusion.

Te wider signicance o this condition is what it tells us aboutourselves. Evidently there is a gushing river o verbal creativity inthe normal human mind, rom which both artistic invention andlying are drawn. We are born storytellers, spinning narrative outo our experience and imagination, straining against the leash thatkeeps us tethered to reality. Tis is a wonderul thing; it is whatgives us our ability to conceive o alternative utures and dierentworlds. And it helps us to understand our own lives through theentertaining stories o others. But it can lead us into trouble, par-ticularly when we try to persuade others that our inventions arereal. Most o the time, as our stories bubble up to consciousness,we exercise our cerebral censors, controlling which stories we tell,and to whom. Yet people lie or all sorts o reasons, including the

During a now-amous libel case in 1996, Jonathan Aitken, aormer cabinet minister, recounted a tale to illustrate the horrorshe endured aer a national newspaper tainted his name. He toldo how, on leaving his home in Westminster one morning with histeenage daughter, he ound himsel stampeded by a documen-tary crew. Upset and scared by the crews aggressive behaviour, hisdaughter burst into tears, he said, and Aitken bundled her into hisministerial car. But as they drove away he realised that they werebeing ollowed by the journalists in their van. A hair-raising chaseacross central London ensued. Te journalists were only shakeno when Aitken executed a cunning deception: he stopped at theSpanish embassy and swapped vehicles.Te case, which stretched on or more than two years, involveda series o claims made by the Guardian about Aitkens relation-ships with Saudi arms dealers, including meetings he allegedlyheld with them on a trip to Paris while he was a government min-ister. What amazed many in hindsight was the sheer superfuity othe lies Aitken told during his testimony. Some were necessary tomaintain his original lie, but others were told, it appeared, or the

sheer thrill o invention. As Aitken stood at the witness stand andpiled lie upon lieapparently carried away by the improvisatoryact o creativityits possible that he elt similar to Brando duringone o his perormances. Aitkens case collapsed in June 1997,when the deence nally ound indisputable evidence about hisParis trip. Until then, Aitkens charm, fuency and fair or theatri-cal displays o sincerity looked as i they might bring him victory.Te rst big dent in his aade came just days beore, when adocumentary crew submitted the unedited rushes o their stam-pede encounter with Aitken outside his home. Tey revealed thatnot only was Aitkens daughter not with him that day (when hewas indeed doorstepped), but also that the minister had simplygot into his car and drove o, with no vehicle in pursuit.

O course, unlike Aitken, actors, playwrights and novelists arenot literally attempting to deceive us, because the rules are laidout in advance: come to the theatre, or open this book, and welllie to you. Perhaps this is why we elt it necessary to invent art inthe rst place: as a sae space into which our lies can be corralled,and channelled into something socially useul. Te key way inwhich artistic lies dier rom normal lies, and rom the honestlying o chronic conabulators, is that they have a meaning andresonance beyond their creator. Te liar lies on behal o himsel;the artist tell lies on behal o everyone. I writers have a compul-sion to narrate, they compel themselves to nd insights aboutthe human condition. Mario Vargas Llosa has written that novelsexpress a curious truth that can only be expressed in a urtiveand veiled ashion, masquerading as what it is not. Art is a liewhose secret ingredient is truth

economist.com APRIL 2012

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

22/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

23/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

24/27

i economist.com APRIL 2012

2012 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part o it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any orm by any means, electromechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the proir permission o The Economist Newspaper Limited.

Editorial

Editor-in-Chie | Adam Moss

Executive Editor | John HomansEditorial Director | Jared HohltManaging Editor | Ann ClarkeDeputy Editor | Jon GluckDesign Director | Thomas AlbertyPhotography Director | Jody Quon

Culture Editor | Lane BrownStrategist Editor | Ashlea HalpernNews Editor | James BurnettFeatures Editor | David HaskellSenior Editors | Rachel Baker, Christopher Bonanos, Raha Nadda, Carl RosenFood Editors | Robert Patronite, Robin RaiseldFashion Director | Amy LaroccaAssociate Editors | Patti Greco, Ben Mathis-LilleyEditor-at-Large | Carl Swanson

Advertising

Call 212-508-0876

Publisher | Lawrence C. BursteinExecutive Director, Print and Integrated Sales | Leslie FarrandAdvertising Business Manager | Nathan WhitneyAdvertising Coordinator | Melissa NappiMarketplace, Director, Printed and Integrated Sales, New York | Michael TresserMarketplace, Production Manager | Manny GomesMarketplace, Assistant Production Manager | Linden HassCulture and Entertainment Director | Ellen Wilk-HarrisLuxury Goods & Retail Director | Kira KriegerReal Estate & Automotive Director | Jim MarronInternational Travel Manager | Elaine ShuiSpirits, Food and Beverage Manager | Zach MaderAccount Managers | Katie Gowdy, Ian Hopping, Melissa M. Montgomery, Kathryn Pau, Holly Boucher, Gary McNealis, Bonnie Meyers Cohen, Adrienne WaunMidwest Ofce | Michelle Morris, 312-377-2207Southwest Ofce | Jane Saell, 310-315-0914Northwest Ofce | Kim Abramson, 415-705-6772Southeast Ofce | Robert H. Stites, 770-491-1419Canada | Chris Brown Media Services International, 905-238-9228Italy | Francesco Ravanello, Carla Villa Studio Villa, 011-39-0231-1662Integrated Sales Planners | Megan Shannon, Melissa Sobel, Ellen Benveniste, Melissa Lawson, Gina Minerbi, Sarah Rehfeld, Theresa Bunce, Sara Idacavage

Marketing

Executive Director, Creative and Marketing Services | Sona Hacherian HostedeExecutive Director o Business Development | Serena Torrey

Operations & Circulation

Chie Operating Ofcer | Kit TaylorDirector o Circulation | Kenneth T. SheldonChie Financial Ofcer | Adelina Pepenilla

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

25/27

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

26/27

economist.com APRIL 2012

2 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part o it may be repr oduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any orm by any means, electronichanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the proir permission o The Economist Newspaper Limited.

Editorial

Editor-in-Chie

Executive EditorEditorial DirectorManaging Editor

Deputy EditorDesign Director

Photography Director

Culture EditorStrategist Editor

News EditorFeatures EditorSenior Editors

Food EditorsFashion Director

Associate Editors |Editor-at-Large

Advertising

Call 212-508-0876Publisher

Executive Director, Print and Integrated SalesAdvertising Business Manager

Advertising Coordinatorarketplace, Director, Printed and Integrated Sales, New York

Marketplace, Production ManagerMarketplace, Assistant Production Manager

Culture and Entertainment DirectorLuxury Goods & Retail Director

Real Estate & Automotive DirectorInternational Travel Manager

Spirits, Food and Beverage ManagerAccount Managers

Midwest OfceSouthwest OfceNorthwest OfceSoutheast Ofce

CanadaItaly

Integrated Sales Planners

Marketing

Executive Director, Creative and Marketing ServicesExecutive Director o Business Development

Operations& Circulation

Chie Operating OfcerDirector o CirculationChie Financial Ofcer

Adam Moss

John HomansJared HohltAnn ClarkeJon GluckThomas AlbertyJody Quon

Lane BrownAshlea HalpernJames BurnettDavid HaskellRachel Baker, Christopher Bonanos, Raha Nadda, Carl RosenRobert Patronite, Robin RaiseldAmy LaroccaPatti Greco, Ben Mathis-LilleyCarl Swanson

Lawrence C. BursteinLeslie FarrandNathan WhitneyMelissa NappiMichael TresserManny GomesLinden HassEllen Wilk-HarrisKira KriegerJim MarronElaine ShuiZach MaderKatie Gowdy, Ian Hopping, Melissa M. Montgomery, Kathry Pau, Holly Boucher, Gary McNealis, Bonnie Meyers Cohen, Adrienne WaunMichelle Morris, 312-377-2207Jane Saell, 310-315-0914Kim Abramson, 415-705-6772Robert H. Stites, 770-491-1419Chris Brown Media Services International, 905-238-9228Francesco Ravanello, Carla Villa Studio Villa, 011-39-0231-1662Megan Shannon, Melissa Sobel, Ellen Benveniste, Melissa Lawson, Gina Minerbi, Sarah Rehfeld, Theresa Bunce, Sara Idacavage

Sona Hacherian HostedeSerena Torrey

Kit TaylorKenneth T. SheldonAdelina Pepenilla

-

7/31/2019 Andi Fink - Project Five

27/27

Forme,thehardestpartofthisprojectwascomingupwithcohesivetextdesignand

creatingmoremeaningthroughthevisualsthatIputinthemagazineitself.Itreally

helpedmetocreateword/thoughtbubblessurroundingthetopicsofthearticlesI

choseandthencreatemymagazinespreadsfromthere.Iwantedtomakea

magazinethatcentersaroundpolicyandeconomicslookmorelikeamagazinethat

centersaroundart,andthiswascertainlyadifficulttask.

![[03] Tribologia - Andi](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/55cf9743550346d0339098a3/03-tribologia-andi.jpg)