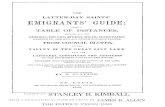

Analysis of the Return Emigrants’ State of...

Transcript of Analysis of the Return Emigrants’ State of...

149

Chapter VII

Analysis of the Return Emigrants’State of Health

7.1. Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to analyse the current state of health of the return

emigrants from the six GCC countries and, to evaluate its socioeconomic implications.

The incidence and prevalence rates of chronic disease morbidity in any population or in

any of its sub groups could be the upshot of a large variety of reasons ranging from

hereditary factors to environmental influences. Chronic diseases, in general, are

degenerative and, very often, have been linked to work disability, early retirement, and

reduced productivity. Currently, chronic conditions are responsible for sixty per cent of

the global disease burden. They are increasing such that by the year 2020 developing

countries can expect eighty per cent of their disease burden come from chronic problems

(WHO, 2002). Exorbitant treatment expenses and that too for a long period of time might

strike at the root of family budgets leading to the impoverishment of many.

The enormity of economic problems related to chronic diseases among the return

emigrants has to be gauged through the analysis of primary data collected for the purpose.

The previous chapter serves as precursor for the analysis in this chapter as the

measurement of health status, independent of the socioeconomic, demographic and

environmental background of the people under investigation might be misleading. Here,

the analysis begins with a comparative evaluation of the prevalence rate of chronic disease

morbidity among return emigrants from the Gulf.

7.2. Chronic Disease Morbidity among Return Emigrants

In the case of chronic degenerative disease the morbid process is irreversible even

though at intermittent but short intervals the afflicted individuals may feel relieved. That

is, recovery is not possible and an individual who becomes ill at a certain time remains ill

until death and, therefore, this investigation adopted a one year recall period and, only the

clinically diagnosed cases that lasted for more than six months were taken into account so

as to absorb the extent of the problem. The enormity of the problem, however, can well be

understood only when the results are placed in comparison with the comprehensive cross

150

sectional studies conducted in Kerala during the past and, therefore, such an attempt is

made here.

Table 7.1: Prevalence Rate of Chronic Disease Morbidity among Return Emigrantsagainst all Kerala Results from Selected Studies

(Per 1000 Population)

Year Study Prevalence Rate

1974 NSSO 28th Round (Rural Kerala) 84

1987 Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad 138

1993 NCAER (Rural Kerala) 65

1993 NCAER (Urban Kerala) 50

1996 Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad 115

1998 NSSO 52nd Round (Rural Kerala) 38

1998 NSSO 52nd Round (Urban Kerala) 27

1999 Panikar 59

2004 Ashokan (Rural Kasaragod) 155

2008 Kerala Migration Survey 2007 150

2011 Sample Survey 344

Sources: Different Reports and Studies; Sample Survey

The results of selected studies, on the general population of Kerala, exemplify ample

inconsistency, with a minimum prevalence rate of 27 for urban Kerala (NSSO, 1998) and

a maximum of 155 for rural Kasaragod (Ashokan, 2004). A methodical scrutiny of this

divergence, however, is beyond the scope of this study. The morbidity prevalence rate

among the return emigrants, vis-à-vis the broad Kerala pattern, as revealed by the sample

data, nevertheless, shows a different picture with 344 per thousand people. This result is

quite disturbing in view of the fact that only eight non-communicable chronic diseases –

Cardiovascular, Arthritis, Diabetes, Hypertension, Asthma, Cancer, Renal, and Cholesterol

– were incorporated in the study. Three probable explanations could be suggested to

describe the factors contributed to the observation of high prevalence rate in the sample

survey: (i) the general trend of shift, over the years, in the morbidity pattern of Kerala,

from communicable to non-communicable diseases; (ii) the inclusion of two main clinical

risk factors – hypercholesterolemia and hypertension in the list of chronic diseases (iii) the

contribution of migration related stressors as well as lifestyle and working and living

151

environment during overseas stay. The rationale in support of the categorization of the

irreversible cases of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension as diseases, in this study,

stems from the ‘declared irreversibility’ (the return emigrants recalled instances of such

pronouncement by the physicians they had consulted) of such clinically diagnosed risk

factors and consequently the prescriptions for lifelong medications. An explicit exposé of

the true picture of morbidity pattern, therefore, warrants a delineation of disease specific

morbidity rate among return emigrants compared to the overall pattern in Kerala.

Table 7.2: Disease Specific Prevalence Rate among Return Emigrants vis-à-vis theGeneral Pattern in Kerala

Chronic DiseasePrevalence Rate (per 1000)

Return Emigrants Kerala Overall*

Cardiovascular 86 81Arthritis 06 43Diabetes 225 201Hypertension 256 242Asthma 17 85Cancer 14 10Renal 28 11Cholesterol 169 56Sources: Sample Survey; Zachariah & Rajan (2008)Note: *The figures are calculated from KMS 2007

The return emigrants’ soaring susceptibility vis-à-vis the general population in Kerala,

especially, to hypertension (256/10000), diabetes (225/1000), cholesterol (169/1000),

Cancer (14/10000, Renal (28/1000) and cardiovascular (86/1000) diseases (primarily heart

disease and stroke), was explicit in the survey data (see table 7.2). The only respite was the

relatively low prevalence rate of arthritis and asthma among the return emigrants. The

inherent problems – both hereditary and environmental – that the return emigrants

confronted during their pre emigration phase and that could have contributed, at least

partially, to their present predicament were assumed, in the present study, to be common

problems that contribute many of the chronic diseases that plague our society today and,

therefore were equally applicable to both emigrants and non-emigrants. The prevalence

rate of chronic disease morbidity and its observed relationships with the return emigrants’

demographic features like age; socioeconomic backgrounds; overseas working and living

152

environment; and their exposure to probable risk factors are elucidated in the following

sections of this chapter.

7.3. Chronic Disease Morbidity among Different Age Groups

It is a global phenomenon that a heavy burden of chronic disease falls on older

groups. National Sample Survey data (NSS 1995-96) confirmed a higher prevalence of

morbidity (162/1000) among older populations in Kerala. However, the early onset of

chronic diseases, among the return emigrants, as substantiated by the survey data (see

table 7.3) is quite startling.

Table 7.3: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Age Group

Age Group Return Emigrants Return Emigrantswith Chronic Disease

Prevalence Rate(per 1000)

20 – 29 97 13 134

30 – 39 124 24 194

40 – 49 69 35 507

50 – 59 50 37 740

60+ 20 15 750

Overall 360 124 344

Source: Sample Survey

More than fifty per cent of the return emigrants in the age group 40 – 49 were

afflicted by one or the other of the chronic diseases. The prevalence rates were

increasingly and alarmingly high for 50 – 59 (740/1000) and 60 plus (750/1000) age

groups. This, unequivocally, indicated that the factors other than age could be better

predictors for chronic disease among the return emigrants in Kerala.

7.4. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Religion

Though the religious faith or affinity of the return emigrants had nothing to do with

their morbidity, the survey data showed interesting results. The morbidity prevalence rate

was highest among Christians (439/1000) and lowest among Hindus (314/1000). Muslims

153

had a prevalence rate of 330 per 1000. Even though the analytical examination of this

inconsistency in the prevalence rate is beyond the scope of the study, a further

examination revealed that the Christian return emigrants had the highest prevalence rate of

hypertension and cholesterol. Incidentally, they also had the highest post return

unemployment rate (38 per cent) and the maximum post return stay period at home (5.5

years).

Figure 7.1:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Religion

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.5. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Marital Status

Prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity by marital status of the return emigrants

was confounded by the effects of age, as prevalence rates, as expected, were high for those

belonging to higher age groups, naturally, the ‘married’ group fell into the category of

high prevalence group.

Here, the ‘single’ category meant unmarried return emigrants at the time of the

survey. They represented the least prevalence rate (143/1000) category among the three

groups based on marital status (see figure 7.2). The mean ages of the ‘single’ (28 years),

‘married’ (41 years) and the ‘divorced/separated’ (33 years) explain, beyond doubt, the

discrepancy in the prevalence rates.

314

HINDU

153

had a prevalence rate of 330 per 1000. Even though the analytical examination of this

inconsistency in the prevalence rate is beyond the scope of the study, a further

examination revealed that the Christian return emigrants had the highest prevalence rate of

hypertension and cholesterol. Incidentally, they also had the highest post return

unemployment rate (38 per cent) and the maximum post return stay period at home (5.5

years).

Figure 7.1:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Religion

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.5. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Marital Status

Prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity by marital status of the return emigrants

was confounded by the effects of age, as prevalence rates, as expected, were high for those

belonging to higher age groups, naturally, the ‘married’ group fell into the category of

high prevalence group.

Here, the ‘single’ category meant unmarried return emigrants at the time of the

survey. They represented the least prevalence rate (143/1000) category among the three

groups based on marital status (see figure 7.2). The mean ages of the ‘single’ (28 years),

‘married’ (41 years) and the ‘divorced/separated’ (33 years) explain, beyond doubt, the

discrepancy in the prevalence rates.

330

439

MUSLIM CHRISTIAN

153

had a prevalence rate of 330 per 1000. Even though the analytical examination of this

inconsistency in the prevalence rate is beyond the scope of the study, a further

examination revealed that the Christian return emigrants had the highest prevalence rate of

hypertension and cholesterol. Incidentally, they also had the highest post return

unemployment rate (38 per cent) and the maximum post return stay period at home (5.5

years).

Figure 7.1:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Religion

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.5. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Marital Status

Prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity by marital status of the return emigrants

was confounded by the effects of age, as prevalence rates, as expected, were high for those

belonging to higher age groups, naturally, the ‘married’ group fell into the category of

high prevalence group.

Here, the ‘single’ category meant unmarried return emigrants at the time of the

survey. They represented the least prevalence rate (143/1000) category among the three

groups based on marital status (see figure 7.2). The mean ages of the ‘single’ (28 years),

‘married’ (41 years) and the ‘divorced/separated’ (33 years) explain, beyond doubt, the

discrepancy in the prevalence rates.

154

Figure 7.2:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Marital Status

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.6. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Education

The level of education has played and still continues to play a crucial role in the

matters of health all over the world. The prevalence of chronic disease morbidity is

generally high among the uneducated or among the people with a low level of education,

owing to their economic backgrounds and greater vulnerability to behavioural risk factors.

The type, nature, and characteristics different occupations they are employed with also

enhance their exposure to risk factors.

The classification of return emigrants into groups – secondary and above, and below

secondary – yielded reasonably expected results, but the magnitude of discrepancy in the

prevalence rate between the two groups was startling. One out of every two return

emigrants, who had only ‘below secondary’ level of education, suffered from at least one

of the chronic diseases listed. The prevalence rate was slightly more than thirty per cent

among the ‘secondary or above’ educated return emigrants.

143

SINGLE

154

Figure 7.2:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Marital Status

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.6. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Education

The level of education has played and still continues to play a crucial role in the

matters of health all over the world. The prevalence of chronic disease morbidity is

generally high among the uneducated or among the people with a low level of education,

owing to their economic backgrounds and greater vulnerability to behavioural risk factors.

The type, nature, and characteristics different occupations they are employed with also

enhance their exposure to risk factors.

The classification of return emigrants into groups – secondary and above, and below

secondary – yielded reasonably expected results, but the magnitude of discrepancy in the

prevalence rate between the two groups was startling. One out of every two return

emigrants, who had only ‘below secondary’ level of education, suffered from at least one

of the chronic diseases listed. The prevalence rate was slightly more than thirty per cent

among the ‘secondary or above’ educated return emigrants.

407

333

MARRIED DIVORCED/SEPARATED

154

Figure 7.2:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Marital Status

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.6. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Education

The level of education has played and still continues to play a crucial role in the

matters of health all over the world. The prevalence of chronic disease morbidity is

generally high among the uneducated or among the people with a low level of education,

owing to their economic backgrounds and greater vulnerability to behavioural risk factors.

The type, nature, and characteristics different occupations they are employed with also

enhance their exposure to risk factors.

The classification of return emigrants into groups – secondary and above, and below

secondary – yielded reasonably expected results, but the magnitude of discrepancy in the

prevalence rate between the two groups was startling. One out of every two return

emigrants, who had only ‘below secondary’ level of education, suffered from at least one

of the chronic diseases listed. The prevalence rate was slightly more than thirty per cent

among the ‘secondary or above’ educated return emigrants.

155

Figure 7.3:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Education

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.7. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Overseas Destination

There were pervasive differences in prevalence rates among emigrants returned from

different destinations in the GCC region (see table 7.4).

Table 7.4: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by

Overseas Destination

Country ofEmployment

ReturnEmigrants

Return Emigrantswith Chronic Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)UAE 106 25 236

Saudi Arabia 139 62 446

Oman 44 16 364

Kuwait 20 7 350

Bahrain 16 5 313

Qatar 35 9 257

Overall 360 124 344

Source: Sample Survey

Return emigrants from Saudi Arabia had the highest prevalence rate (446/1000).

Incidentally, the maximum period of overseas stay was in Saudi Arabia (8.29 years on

average) compared to any other destination. Exposures to most of the risk factors like job

characteristics were also at their peak in Saudi Arabia. The fact that the maximum number

of return emigrants in Kerala had come from Saudi Arabia did accentuate the significance

of this high prevalence rate. The other GCC countries with high prevalence rates were

BELOW SECONDARY

SECONDARY AND ABOVE

155

Figure 7.3:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Education

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.7. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Overseas Destination

There were pervasive differences in prevalence rates among emigrants returned from

different destinations in the GCC region (see table 7.4).

Table 7.4: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by

Overseas Destination

Country ofEmployment

ReturnEmigrants

Return Emigrantswith Chronic Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)UAE 106 25 236

Saudi Arabia 139 62 446

Oman 44 16 364

Kuwait 20 7 350

Bahrain 16 5 313

Qatar 35 9 257

Overall 360 124 344

Source: Sample Survey

Return emigrants from Saudi Arabia had the highest prevalence rate (446/1000).

Incidentally, the maximum period of overseas stay was in Saudi Arabia (8.29 years on

average) compared to any other destination. Exposures to most of the risk factors like job

characteristics were also at their peak in Saudi Arabia. The fact that the maximum number

of return emigrants in Kerala had come from Saudi Arabia did accentuate the significance

of this high prevalence rate. The other GCC countries with high prevalence rates were

507

303

155

Figure 7.3:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Education

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.7. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Overseas Destination

There were pervasive differences in prevalence rates among emigrants returned from

different destinations in the GCC region (see table 7.4).

Table 7.4: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by

Overseas Destination

Country ofEmployment

ReturnEmigrants

Return Emigrantswith Chronic Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)UAE 106 25 236

Saudi Arabia 139 62 446

Oman 44 16 364

Kuwait 20 7 350

Bahrain 16 5 313

Qatar 35 9 257

Overall 360 124 344

Source: Sample Survey

Return emigrants from Saudi Arabia had the highest prevalence rate (446/1000).

Incidentally, the maximum period of overseas stay was in Saudi Arabia (8.29 years on

average) compared to any other destination. Exposures to most of the risk factors like job

characteristics were also at their peak in Saudi Arabia. The fact that the maximum number

of return emigrants in Kerala had come from Saudi Arabia did accentuate the significance

of this high prevalence rate. The other GCC countries with high prevalence rates were

507

156

Oman, Kuwait and Bahrain. The return emigrants from Qatar and UAE had the least

prevalence rate. The mean duration of stay by the return emigrants in these two countries

was relatively less.

7.8. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Overseas Occupation

The effect of overseas occupation on prevalence of chronic disease morbidity among

return emigrants follows, largely, from their long term exposure to agents with latent

effects. It was found that those who were working as domestic servants, construction

workers, farm workers and other unskilled workers had the highest prevalence rate

(415/1000). The five broad occupational groups (see table 7.5) indicated, clearly, that the

return emigrants who were classified in the ‘first group’ had the least prevalence rate. In

fact, this grouping was made basically on the basis of prevalence rate and not the other

way round. Those who were having closer prevalence rates were put together to form a

group.

Table 7.5: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by OverseasOccupation

Occupational Group ReturnEmigrants

ReturnEmigrants

with ChronicDisease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

1Bank, Engineer, IT/IT related,Manager/Accountant/OfficeWork, Cashier, Overseer,Supervisor, Teacher, Business

35 7 200

2Electrician, Fire service,Plumber,Manufacturing, Petroleum,Natural Gas, Cold Storage,

58 16 276

3Driver/Other TransportationWorker, Salespeople, MarketingRepresentative

135 47 348

4Barber, Mason, Tailor, Painter,Carpenter, Welder, Mechanic,Goldsmith, Fabrication Worker

50 20 400

5Housekeeper/Domestic Servant,Construction, Farm and otherUnskilled Workers

82 34 415

Overall 360 124 344Source: Sample Survey

157

7.9. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Job Characteristics Abroad

All occupations in the Gulf exemplified any one, two or more of the characteristics

such as high physical labour, noise, work stress, and worry about job security. The link

between perceived job characteristics and chronic disease morbidity as shown in the table

(see table 7.6) underscores the adverse effects of job characteristics on human health.

Table 7.6: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Reported JobCharacteristics Abroad

Source: Sample Survey

Return emigrants who were employed in occupations that required heavy physical

labour had the highest prevalence rate (603/1000) whereas the prevalence rate among

return emigrants who confirmed that their occupation did not entail heavy physical labour

was much lower (102/1000). On the whole, the occurrence and addition of every adverse

job characteristic amplified the prevalence rate and their absence proved the opposite.

Since health status, in this study, is defined in terms of chronic disease morbidity – a

categorical dichotomous outcome – logistic regression is the appropriate multivariate

analysis. All 360 sample units are included in the analysis.

Job CharacteristicsReturn

Emigrants’Response

Number ofReturn

EmigrantsResponded

ReturnEmigrants

withChronicDisease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

Heavy PhysicalLabour

Yes 174 105 603

No 186 19 102

Noise, Dust,Vapors, Polluted

Air

Yes 201 85 423

No 159 39 245

Work Stress Yes 199 77 387

No 161 47 292

Overtime/LongWork Hours

Yes 208 80 385

No 152 44 289

Worry About JobSecurity

Yes 81 38 469

No 279 86 308

158

Table 7.7: Amount of Variation Explained by the Model

Model Summary

Source: Sample Survey

Nagelkerke’s R2 is found to be 0.837, indicating a strong relationship between the

predictors and prediction. It shows that about 84 per cent of the variation in the outcome

(chronic diseases morbidity) is explained by this model.

Table 7.8: Estimates of the Logistic Regression Model

Variables in the Equation

B S.E. Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% C.I. for

EXP(B)

Lower UpperStep1* AWCGULF .450 .086 27.569 1 .000 1.569 1.326 1.856

AGE .108 .014 61.911 1 .000 1.115 1.085 1.145

ASSET .038 .011 12.235 1 .000 1.039 1.017 1.061

INCOME -.016 .020 .619 1 .431 .984 .945 1.024

CONSTANT-

6.639

.743 79.790 1 .000 .001

Source: Sample Survey

The variables included are: (i) adverse working conditions in the Gulf (AWCGULF),

(ii) current age of the return emigrants (AGE), (iii) total value of household assets

(ASSET), and (iv) current income (INCOME). An all-inclusive assessment of overseas

working condition is made on the bases of job characteristics such as high physical labour;

noise, dust, polluted air; work stress; overtime/long working hours; worry about job

security and harassment from superiors. Equal weights are assigned to every adverse

condition, reported, in order to arrive at a total adverse working condition value index for

Step -2 Loglikelihood

Cox & SnellR Square

NagelkerkeR Square

1 29.850 0.631 0.837

159

each return emigrant. The value ranged between 0 (no adverse condition) and 1 (all

adverse conditions); higher value indicates more adverse conditions.

The Wald estimates give the importance of the contribution of each variable in the

model. The higher the value, the more important it is.

Only statistically significant (p < .05) variables could be treated as predictor variables

in any model and, therefore, all independent variables except the current income (P > 0.05)

of the return emigrants seem to have a bearing on the dependent variable - the presence of

at least one of the identified chronic diseases.

The Exp (B) gives the odds ratio. The odds ratio corresponding to adverse working

condition validates, beyond doubt, the proposition suggested at the beginning of this

study; buildup of one more AWC in the Gulf implies that the return emigrants are 1.569

(95% CI 1.326 – 1.856) more times likely to be inflicted with at least one of the chronic

diseases.

It is an established fact that ageing is one of the major determinants of chronic

disease. Since age is a quantitative numerical variable, an increase of one-year in age has

11.5 per cent (95% CI 8.5% to 14.5%) increase in odds ratio of having chronic disease

morbidity. When household wealth is increased by one unit (Rupees One lakh), the odds

ratio is 1.039 (95% CI 1.017 – 1.061) times as large and therefore return emigrants are

1.039 more times likely to have chronic disease and this underscores the argument that

many chronic diseases are “diseases of affluence” and not of deprivation.

All these results suggest that the age of return emigrants, their working environment

abroad and household assets have statistically significant impact on the health state as

revealed by the respective odds ratio.

7.10. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Period of Overseas Employment

The durations of employment abroad identify the length of exposure to unfavorable

circumstances and, therefore, could be very good predictors of prevalence rates even

though the results obtained cannot be relied upon, completely, as the confounding effects

of age would, definitely, magnify them. The prevalence rate was lowest (230/1000) for the

return emigrants who had up to five years of overseas employment (see table 7.9)

160

Table 7.9: Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants byPeriod of Overseas Employment

Period of OverseasStay (Years)

ReturnEmigrants

Return Emigrantswith Chronic

Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

Up to 5 222 51 230

06 – 10 62 22 355

11 – 15 34 21 618

Above 15 42 30 714

Overall 360 124 344Source: Sample Survey

As the span of overseas stay lengthened, the prevalence rate increased. Pearson’s

correlation between the number of years abroad and the corresponding chronic disease

prevalence rate, worked out for the entire data, showed the existence of a moderately high

degree positive correlation (0.682; sig<0.01) between the two.

7.11. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Satisfaction on Overseas Working Environment

The deteriorating working environment and the resulting decline in job satisfaction

can influence workers’ health in any setting. The return emigrants were asked to make

their statement on the level satisfaction they had on the nature of job and working

conditions in the Gulf. The different levels of satisfaction were put under ‘satisfied’ and

the various level of dissatisfaction under ‘dissatisfied’. Prevalence rates estimated against

the backdrop of return emigrants’ statements exemplify that those who were ‘dissatisfied’

with the overall working environment there had the highest prevalence rate (see figure

7.4). The relationships found suggest that job satisfaction abroad was an important factor

that influenced the health of return emigrants. However, the present health state of return

emigrants might have influenced, at least partially, in evoking the level of satisfaction of a

past experience.

161

Figure 7.4:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Reported Satisfaction on

Overseas Working Environment (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.12. Problems with Fellow Workers and Harassment by Superiors

The return emigrants who were ‘always’ and ‘occasionally’ having problems with the

fellow workers in the Gulf and ‘always’ and ‘occasionally’ subjected to harassment by

superiors had high prevalence rate (see figure 7.5) relative to their counterparts who

‘never’ confronted such troubles.

Figure 7.5:Prevalence Rate of CDM by Problems with Fellow Workers and Harassment from

Superiors (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

262

593

NATURE OF JOB

SATISFIED

476 453

PROBLEMS WITH FELLOW WORKERS

ALWAYS

161

Figure 7.4:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Reported Satisfaction on

Overseas Working Environment (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.12. Problems with Fellow Workers and Harassment by Superiors

The return emigrants who were ‘always’ and ‘occasionally’ having problems with the

fellow workers in the Gulf and ‘always’ and ‘occasionally’ subjected to harassment by

superiors had high prevalence rate (see figure 7.5) relative to their counterparts who

‘never’ confronted such troubles.

Figure 7.5:Prevalence Rate of CDM by Problems with Fellow Workers and Harassment from

Superiors (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

254

588

167

286

NATURE OF JOB WORKING CONDITIONS

SATISFIED DISSATISFIED INDIFFERENT

462

356315 330

PROBLEMS WITH FELLOW WORKERS HARASSMENT BY SUPERIORS

ALWAYS OCCASIONALLY NO NEVER

161

Figure 7.4:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Reported Satisfaction on

Overseas Working Environment (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.12. Problems with Fellow Workers and Harassment by Superiors

The return emigrants who were ‘always’ and ‘occasionally’ having problems with the

fellow workers in the Gulf and ‘always’ and ‘occasionally’ subjected to harassment by

superiors had high prevalence rate (see figure 7.5) relative to their counterparts who

‘never’ confronted such troubles.

Figure 7.5:Prevalence Rate of CDM by Problems with Fellow Workers and Harassment from

Superiors (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

HARASSMENT BY SUPERIORS

162

7.13. Thought about Relatives at Home

It is quite natural that separation from family, especially when compelled to stay in a

far away country, could cause deep sense of loneliness. The return emigrants while in the

Gulf not only suffered from severance, they also had the restiveness as the thoughts about

their inability to look after relatives at home haunted most of them.

Prevalence rate of chronic morbidity was much higher (see figure 7.6) among the

return emigrants who ‘always’ or ‘occasionally’ had such anxiety about their spouses,

children, Parents or other immediate relatives at home.

Figure 7.6:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Frequency of Thought about

Inability to Look after Relatives at Home (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.14. Personal Satisfaction on the Management of Household Affairs by Relatives

A small number of return emigrants, during their overseas stay, did have a little bit of

concern over the management of household affairs by relatives. The extravagant lifestyle

pursued by some households might have contributed towards this. Based on their different

levels of satisfaction on the management of household affairs by relatives, the respondents

were grouped into three categories – satisfied, dissatisfied and indifferent. Estimation of

chronic disease morbidity prevalence rate among the three groups showed that there was

no glaring disparity between the ‘satisfied’ (345/1000) and ‘dissatisfied’ (367/1000)

groups.

280

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

360

CDM BY FREQUENCY OF THOUGHT ABOUT INABILITY TO LOOKAFTER RALATIVES AT HOME

ALWAYS

OCCASIONALLY

NO, NEVER

163

Figure 7.7:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Personal Satisfaction on the

Management of Household Affairs by Relatives (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.15. Nature of Contact with the Host Population

As much as seventy five per cent of the return emigrants had ‘close contact’ with the

host population during their overseas stay. Six per cent of the respondents reported ‘no

contact’. Fifty per cent of the return emigrants who had ‘no contact’ or ‘distant contact’

with the host population was ‘affected’ by chronic diseases while only twenty nine per

cent of the return emigrants who maintained ‘close contact’ was ‘affected’ by chronic

disease.

Figure 7.8:Proportion of Chronic Disease Affected Return Emigrants by their

Nature of Contact with the Host Population during Overseas Employment

Source: Sample Survey

345

PERSONAL SATISFACTION ON THE MANAGEMENT OF HOUSEHOLD AFFAIRS BY RELATIVES

SATISFIED

050

100150200250300

NOCONTACT

NU

MBE

R O

F RE

TURN

EMIG

RAN

TS

163

Figure 7.7:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Personal Satisfaction on the

Management of Household Affairs by Relatives (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.15. Nature of Contact with the Host Population

As much as seventy five per cent of the return emigrants had ‘close contact’ with the

host population during their overseas stay. Six per cent of the respondents reported ‘no

contact’. Fifty per cent of the return emigrants who had ‘no contact’ or ‘distant contact’

with the host population was ‘affected’ by chronic diseases while only twenty nine per

cent of the return emigrants who maintained ‘close contact’ was ‘affected’ by chronic

disease.

Figure 7.8:Proportion of Chronic Disease Affected Return Emigrants by their

Nature of Contact with the Host Population during Overseas Employment

Source: Sample Survey

367

214

PERSONAL SATISFACTION ON THE MANAGEMENT OF HOUSEHOLD AFFAIRS BY RELATIVES

SATISFIED DISSATISFIED INDIFFERENT

NOCONTACT

DISTANTCONTACT

CLOSECONTACT

AFFECTED

NOT AFFECTED

163

Figure 7.7:Prevalence Rate of CDM among Return Emigrants by Personal Satisfaction on the

Management of Household Affairs by Relatives (Per 1000)

Source: Sample Survey

7.15. Nature of Contact with the Host Population

As much as seventy five per cent of the return emigrants had ‘close contact’ with the

host population during their overseas stay. Six per cent of the respondents reported ‘no

contact’. Fifty per cent of the return emigrants who had ‘no contact’ or ‘distant contact’

with the host population was ‘affected’ by chronic diseases while only twenty nine per

cent of the return emigrants who maintained ‘close contact’ was ‘affected’ by chronic

disease.

Figure 7.8:Proportion of Chronic Disease Affected Return Emigrants by their

Nature of Contact with the Host Population during Overseas Employment

Source: Sample Survey

PERSONAL SATISFACTION ON THE MANAGEMENT OF HOUSEHOLD AFFAIRS BY RELATIVES

NOT AFFECTED

164

7.16. Unhealthy Diet, Soft Drinks and Smoking

Unhealthy diet and smoking, like alcohol consumption and sedentary lifestyle, are the

most decisive behavioural risk factors. As much as sixty three per cent of the return

emigrants were fond of unhealthy food and about seventy two per cent consumed soft

drinks (see table 7.10). The results indicated that around fifty five per cent of the return

emigrants were habitual smokers during overseas stay. Though many of them discontinued

the habit on return, around thirty per cent of the return emigrants were smokers at the time

of the survey.

The country specific disaggregated results pointed toward the pervasiveness of risky

behaviours across the entire GCC region. But these descriptive statistics are not sufficient

enough to establish a finite link between the behavioural risk factors and prevalence rate

of chronic disease morbidity among the return emigrants.

Table 7.10: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Consumption ofUnhealthy Food, Soft Drinks, and Smoking Habit by Country of Employment

Country ofEmployment

Number ofReturnEmigrants

Number and Per cent ofReturn Emigrants Consumed Number and

Per cent ofSmokersUnhealthy Food Soft Drinks

UAE 106 64 (60.4) 73 (68.9) 58 (54.7)

Saudi Arabia 139 93 (66.9) 109 (78.4) 80 (57.6)

Oman 44 26 (59.1) 32 (72.7) 24 (54.5)

Kuwait 20 11 (55.0) 12 (60.0) 8 (40.0)

Bahrain 16 10 (62.5) 10 (62.5) 5 (31.3)

Qatar 35 23 (65.7) 23 (65.7) 22 (62.9)

Overall 360 227 (63.1) 259 (71.9) 197 (54.7)

Source: Sample Survey

7.17. Place of Medical Treatment in the Gulf

There was pervasive inequality in the accessibility of health care in the Gulf. Only

thirty four per cent of the respondents were provided with company/government hospital

facilities (see figure 7.9). Thirty per cent had taken recourse to various private hospitals

and clinics while thirty six per cent of them had to be content with self treatment

165

Figure 7.9:Return Emigrants by Place of Treatment in the Gulf

(Per cent)

Source: Sample Survey

The prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity was the highest (383/1000) among

those who sought treatment in clinics and private hospitals in the Gulf (see table 7.11).

This indicates the urgency of the situation they had to face albeit the expenses involved.

The prevalence rate (302/1000) among the ‘self’ treated return emigrants reveals, at least

in part, the inaccessibility, non affordability and discrimination in general of the health

care in the GCC countries.

Table 7.11: Prevalence Rate of CDM by Place of Treatment in the Gulf

Place of TreatmentReturn

EmigrantsReturn

Emigrantswith Chronic

Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

Self 129 39 302Company/Govt. Hospital 124 44 305Private Hospital/Clinic 107 41 383

Overall 360 124 344Source: Sample Survey

7.18. Delay in Seeking Medical Treatment in the Gulf

As much as twenty three per cent of the return emigrants across the GCC region,

irrespective of the place of treatment, had to delay their seeking prompt treatment (see

table 7.12). Saudi Arabia had the largest proportion (25.9 percent) followed by Bahrain

(25 per cent) and United Arab Emirates (23.6 per cent) and, Qatar had the least proportion

(14.3 per cent). Delay in seeking medical treatment is partially a problem of accessibility

25

30

35

40

SELF

36

165

Figure 7.9:Return Emigrants by Place of Treatment in the Gulf

(Per cent)

Source: Sample Survey

The prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity was the highest (383/1000) among

those who sought treatment in clinics and private hospitals in the Gulf (see table 7.11).

This indicates the urgency of the situation they had to face albeit the expenses involved.

The prevalence rate (302/1000) among the ‘self’ treated return emigrants reveals, at least

in part, the inaccessibility, non affordability and discrimination in general of the health

care in the GCC countries.

Table 7.11: Prevalence Rate of CDM by Place of Treatment in the Gulf

Place of TreatmentReturn

EmigrantsReturn

Emigrantswith Chronic

Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

Self 129 39 302Company/Govt. Hospital 124 44 305Private Hospital/Clinic 107 41 383

Overall 360 124 344Source: Sample Survey

7.18. Delay in Seeking Medical Treatment in the Gulf

As much as twenty three per cent of the return emigrants across the GCC region,

irrespective of the place of treatment, had to delay their seeking prompt treatment (see

table 7.12). Saudi Arabia had the largest proportion (25.9 percent) followed by Bahrain

(25 per cent) and United Arab Emirates (23.6 per cent) and, Qatar had the least proportion

(14.3 per cent). Delay in seeking medical treatment is partially a problem of accessibility

COMPANY/GOVT.HOSPITAL PRIVATE

HOSPITAL/CLINIC

3634

30

165

Figure 7.9:Return Emigrants by Place of Treatment in the Gulf

(Per cent)

Source: Sample Survey

The prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity was the highest (383/1000) among

those who sought treatment in clinics and private hospitals in the Gulf (see table 7.11).

This indicates the urgency of the situation they had to face albeit the expenses involved.

The prevalence rate (302/1000) among the ‘self’ treated return emigrants reveals, at least

in part, the inaccessibility, non affordability and discrimination in general of the health

care in the GCC countries.

Table 7.11: Prevalence Rate of CDM by Place of Treatment in the Gulf

Place of TreatmentReturn

EmigrantsReturn

Emigrantswith Chronic

Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

Self 129 39 302Company/Govt. Hospital 124 44 305Private Hospital/Clinic 107 41 383

Overall 360 124 344Source: Sample Survey

7.18. Delay in Seeking Medical Treatment in the Gulf

As much as twenty three per cent of the return emigrants across the GCC region,

irrespective of the place of treatment, had to delay their seeking prompt treatment (see

table 7.12). Saudi Arabia had the largest proportion (25.9 percent) followed by Bahrain

(25 per cent) and United Arab Emirates (23.6 per cent) and, Qatar had the least proportion

(14.3 per cent). Delay in seeking medical treatment is partially a problem of accessibility

166

and availability. Also, there can be the situations that some individuals do not seek

medical treatment unless they are injured or seriously ill.

Table 7.12: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Delay in Seeking MedicalTreatment by Overseas Destination

Country ofEmployment Return

Emigrants

Return Emigrantswith Delay in seeking

TreatmentPer cent

UAE 106 25 23.6

Saudi Arabia 139 36 25.9

Oman 44 8 18.2

Kuwait 20 3 15.0

Bahrain 16 4 25.0

Qatar 35 5 14.3

Overall 360 81 22.5

Source: Sample Survey

The reasons for delay, according to the survey information, were complex and varied.

For instance, fifty six per cent of the respondents did not seek timely treatment in the Gulf

(see figure 7.10) because of their own negligence. But there could be a number of other

composite factors leading to a situation of ‘own negligence’. The other key reasons for

delay were ‘time constraint’ (20 per cent), ‘long distance’ (16 per cent) and ‘non

affordable’ (8 per cent). There was a major shortcoming in this compartmentalization of

reasons as it could not catch the simultaneous occurrence of two or more reasons that

delayed prompt treatment.

Figure 7.10:Return Emigrants by Reasons for Delay in Seeking Medical Treatment in the Gulf

(Per cent)

Source: Sample Survey

8

NONAFFORDABLE

TIMECONSTRAINT

166

and availability. Also, there can be the situations that some individuals do not seek

medical treatment unless they are injured or seriously ill.

Table 7.12: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Delay in Seeking MedicalTreatment by Overseas Destination

Country ofEmployment Return

Emigrants

Return Emigrantswith Delay in seeking

TreatmentPer cent

UAE 106 25 23.6

Saudi Arabia 139 36 25.9

Oman 44 8 18.2

Kuwait 20 3 15.0

Bahrain 16 4 25.0

Qatar 35 5 14.3

Overall 360 81 22.5

Source: Sample Survey

The reasons for delay, according to the survey information, were complex and varied.

For instance, fifty six per cent of the respondents did not seek timely treatment in the Gulf

(see figure 7.10) because of their own negligence. But there could be a number of other

composite factors leading to a situation of ‘own negligence’. The other key reasons for

delay were ‘time constraint’ (20 per cent), ‘long distance’ (16 per cent) and ‘non

affordable’ (8 per cent). There was a major shortcoming in this compartmentalization of

reasons as it could not catch the simultaneous occurrence of two or more reasons that

delayed prompt treatment.

Figure 7.10:Return Emigrants by Reasons for Delay in Seeking Medical Treatment in the Gulf

(Per cent)

Source: Sample Survey

20 16

56

TIMECONSTRAINT

LONG DISTANCE OWNNEGLIGENCE

166

and availability. Also, there can be the situations that some individuals do not seek

medical treatment unless they are injured or seriously ill.

Table 7.12: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Delay in Seeking MedicalTreatment by Overseas Destination

Country ofEmployment Return

Emigrants

Return Emigrantswith Delay in seeking

TreatmentPer cent

UAE 106 25 23.6

Saudi Arabia 139 36 25.9

Oman 44 8 18.2

Kuwait 20 3 15.0

Bahrain 16 4 25.0

Qatar 35 5 14.3

Overall 360 81 22.5

Source: Sample Survey

The reasons for delay, according to the survey information, were complex and varied.

For instance, fifty six per cent of the respondents did not seek timely treatment in the Gulf

(see figure 7.10) because of their own negligence. But there could be a number of other

composite factors leading to a situation of ‘own negligence’. The other key reasons for

delay were ‘time constraint’ (20 per cent), ‘long distance’ (16 per cent) and ‘non

affordable’ (8 per cent). There was a major shortcoming in this compartmentalization of

reasons as it could not catch the simultaneous occurrence of two or more reasons that

delayed prompt treatment.

Figure 7.10:Return Emigrants by Reasons for Delay in Seeking Medical Treatment in the Gulf

(Per cent)

Source: Sample Survey

167

7.19. Visit at Private Doctors in the Gulf

Visiting a private doctor for medical care reflect three important points – urgency of

the problem, absence of substitute on time and, of course, affordability. One out of every

two respondents had visited private doctors, at least once, during their entire stay in the

Gulf. The ‘no visit’ group (see table 7.13) represented fifty per cent of the return

emigrants. They include all those who had ‘self’ treatment plus a few from the group that

enjoyed company or public medical care facility.

Table 7.13: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to the Number of Times theyVisited Private Doctors in the Gulf

Number of Visits Return Emigrants Per cent

No Visit 182 50.5

01 – 05 107 29.7

06 – 10 37 10.3

11 – 15 20 5.6

16 – 20 09 2.5

Above 20 05 1.4

Total 360 100

Source: Sample Survey

7.20. Fee Paid for Consulting Private Doctors in the Gulf

Consultation with private doctors in the Gulf, as in any other place, involved out of

pocket expenditure that many return emigrants found unaffordable. The fee charged by

doctors for a single consultation varied from place to place and even from doctors to

doctors in the same locality. As much as fifty eight per cent of the return emigrants had to

make payment between Rs 500 and Rs 1000 for a single appointment (see table 7.14).

There were instances of doctors stipulating exorbitant fees for consultation depending

upon their area of specialization.

168

Table 7.14: Distribution of Return Emigrants by Fee Paid for a Single Consultation

Fee Paid for SingleConsultation (Rs)

ReturnEmigrants

Return EmigrantsPer cent

CumulativePer cent

Below 500 20 11.2 11.2

500 – 1000 103 57.8 69.0

1000 – 1500 20 11.2 80.2

1500 – 2000 17 9.6 89.8

2000 – 2500 06 3.4 93.2

2500 – 3000 06 3.4 96.6

Above 3000 06 3.4 100

Overall 178 100 100

Source: Sample Survey

7.21. Satisfaction on Consultation with Private Doctors in the Gulf

The return emigrants were asked to recollect their personal experience of consultation

with private doctors in the Gulf. A greater proportion of them (86.5 per cent) testified that

they were satisfied with every single consultation there. This implied that the remaining

persons (13.5 per cent) were dissatisfied in the matter of consultation. They had their own

reasons for dissatisfaction. As much as forty two per cent of the ‘dissatisfied’ admitted

‘too much cost’ as the prime reason behind their dissatisfaction while about twenty nine

per cent disclosed ‘communication problems’ as the underlying factor (see figure 7.11).

Unfriendly attitudes of the doctors and wrong diagnosis were also cited as causal factors

for dissatisfaction with doctors.

Figure 7.11:Return Emigrants by Reasons for Dissatisfaction with Private Doctors in the Gulf

Source: Sample Survey

0

10

20

30

40

50

168

Table 7.14: Distribution of Return Emigrants by Fee Paid for a Single Consultation

Fee Paid for SingleConsultation (Rs)

ReturnEmigrants

Return EmigrantsPer cent

CumulativePer cent

Below 500 20 11.2 11.2

500 – 1000 103 57.8 69.0

1000 – 1500 20 11.2 80.2

1500 – 2000 17 9.6 89.8

2000 – 2500 06 3.4 93.2

2500 – 3000 06 3.4 96.6

Above 3000 06 3.4 100

Overall 178 100 100

Source: Sample Survey

7.21. Satisfaction on Consultation with Private Doctors in the Gulf

The return emigrants were asked to recollect their personal experience of consultation

with private doctors in the Gulf. A greater proportion of them (86.5 per cent) testified that

they were satisfied with every single consultation there. This implied that the remaining

persons (13.5 per cent) were dissatisfied in the matter of consultation. They had their own

reasons for dissatisfaction. As much as forty two per cent of the ‘dissatisfied’ admitted

‘too much cost’ as the prime reason behind their dissatisfaction while about twenty nine

per cent disclosed ‘communication problems’ as the underlying factor (see figure 7.11).

Unfriendly attitudes of the doctors and wrong diagnosis were also cited as causal factors

for dissatisfaction with doctors.

Figure 7.11:Return Emigrants by Reasons for Dissatisfaction with Private Doctors in the Gulf

Source: Sample Survey

COST TOO MUCH

UNFRIENDLY DOCTOR

COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS

WRONG DIAGNOSIS

168

Table 7.14: Distribution of Return Emigrants by Fee Paid for a Single Consultation

Fee Paid for SingleConsultation (Rs)

ReturnEmigrants

Return EmigrantsPer cent

CumulativePer cent

Below 500 20 11.2 11.2

500 – 1000 103 57.8 69.0

1000 – 1500 20 11.2 80.2

1500 – 2000 17 9.6 89.8

2000 – 2500 06 3.4 93.2

2500 – 3000 06 3.4 96.6

Above 3000 06 3.4 100

Overall 178 100 100

Source: Sample Survey

7.21. Satisfaction on Consultation with Private Doctors in the Gulf

The return emigrants were asked to recollect their personal experience of consultation

with private doctors in the Gulf. A greater proportion of them (86.5 per cent) testified that

they were satisfied with every single consultation there. This implied that the remaining

persons (13.5 per cent) were dissatisfied in the matter of consultation. They had their own

reasons for dissatisfaction. As much as forty two per cent of the ‘dissatisfied’ admitted

‘too much cost’ as the prime reason behind their dissatisfaction while about twenty nine

per cent disclosed ‘communication problems’ as the underlying factor (see figure 7.11).

Unfriendly attitudes of the doctors and wrong diagnosis were also cited as causal factors

for dissatisfaction with doctors.

Figure 7.11:Return Emigrants by Reasons for Dissatisfaction with Private Doctors in the Gulf

Source: Sample Survey

COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS

169

7.22. Medical Insurance Coverage in the Gulf

Contract workers in the Gulf were usually excluded from all government supported

welfare schemes including medical insurance coverage for workers. On the whole, about

twenty eight per cent of the respondents had medical insurance coverage in the Gulf (see

table 7.15). The proportion of insured varied from country to country in the GCC region.

Since all the medical insurance coverage, other than ‘self’, in the gulf, were linked to the

period of employment there, all of them ceased to exist with the employment contract.

Table 7.15: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Medical InsuranceCoverage during Overseas Stay by Country of Employment

Country ofEmployment

ReturnEmigrants

Number and Per cent ofReturn Emigrants

CoveredUAE 106 28 (26.4)

Saudi Arabia 139 40 (28.8)

Oman 44 17 (38.6)

Kuwait 20 02 (10.0)

Bahrain 16 04 (25.0)

Qatar 35 10 (28.6)

Overall 360 101(28.1)

Source: Sample Survey

The medical insurance premiums for 86 persons of the 101 insured were paid by their

employers in the Gulf while 11 persons had to make fully ‘self’ payment and another 4

had to make partial payment (see figure 7.12).

Figure 7.12:

Return Emigrants by their Medical Insurance Premium Paying Agencies in the Gulf

Source: Sample Survey

4

11

SELF

169

7.22. Medical Insurance Coverage in the Gulf

Contract workers in the Gulf were usually excluded from all government supported

welfare schemes including medical insurance coverage for workers. On the whole, about

twenty eight per cent of the respondents had medical insurance coverage in the Gulf (see

table 7.15). The proportion of insured varied from country to country in the GCC region.

Since all the medical insurance coverage, other than ‘self’, in the gulf, were linked to the

period of employment there, all of them ceased to exist with the employment contract.

Table 7.15: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Medical InsuranceCoverage during Overseas Stay by Country of Employment

Country ofEmployment

ReturnEmigrants

Number and Per cent ofReturn Emigrants

CoveredUAE 106 28 (26.4)

Saudi Arabia 139 40 (28.8)

Oman 44 17 (38.6)

Kuwait 20 02 (10.0)

Bahrain 16 04 (25.0)

Qatar 35 10 (28.6)

Overall 360 101(28.1)

Source: Sample Survey

The medical insurance premiums for 86 persons of the 101 insured were paid by their

employers in the Gulf while 11 persons had to make fully ‘self’ payment and another 4

had to make partial payment (see figure 7.12).

Figure 7.12:

Return Emigrants by their Medical Insurance Premium Paying Agencies in the Gulf

Source: Sample Survey

86

SELF EMPLOYER PARTLY SELF

169

7.22. Medical Insurance Coverage in the Gulf

Contract workers in the Gulf were usually excluded from all government supported

welfare schemes including medical insurance coverage for workers. On the whole, about

twenty eight per cent of the respondents had medical insurance coverage in the Gulf (see

table 7.15). The proportion of insured varied from country to country in the GCC region.

Since all the medical insurance coverage, other than ‘self’, in the gulf, were linked to the

period of employment there, all of them ceased to exist with the employment contract.

Table 7.15: Distribution of Return Emigrants according to Medical InsuranceCoverage during Overseas Stay by Country of Employment

Country ofEmployment

ReturnEmigrants

Number and Per cent ofReturn Emigrants

CoveredUAE 106 28 (26.4)

Saudi Arabia 139 40 (28.8)

Oman 44 17 (38.6)

Kuwait 20 02 (10.0)

Bahrain 16 04 (25.0)

Qatar 35 10 (28.6)

Overall 360 101(28.1)

Source: Sample Survey

The medical insurance premiums for 86 persons of the 101 insured were paid by their

employers in the Gulf while 11 persons had to make fully ‘self’ payment and another 4

had to make partial payment (see figure 7.12).

Figure 7.12:

Return Emigrants by their Medical Insurance Premium Paying Agencies in the Gulf

Source: Sample Survey

170

Many other return emigrants were insured for accidents at the work place and they

had to access care for any other health problems by spending their hard earned money.

Since prompt medical care in the Gulf was primarily linked to ability to pay, a look at the

prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity in comparison with the return emigrants’

overseas income level is essential.

7.23. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Income from Employment Abroad

The overall mean income from employment abroad was worked out to be Rs 16,379

per month. Based on this estimation, Rs 20,000 was fixed, logically, as the benchmark to

distinguish between two groups of income recipients – below Rs 20, 000 income group

and, Rs 20, 000 and above income group. Chronic disease prevalence rate arrived at on

this basis revealed that the group with an average income of less than Rs 20, 000 per

month had a higher prevalence rate (356/1000) compared to the prevalence rate

(318/1000) of the other group with a monthly mean income of Rs 20, 000 and above (see

figure 7.13)

Figure 7.13:Prevalence Rate of CDM by Monthly Income from Employment Abroad

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.24. Chronic Disease Morbidity by duration of Post Return Phase

Subsequent to the eventual return from the Gulf, all the respondents were staying with

their relatives at home. As each individual had returned at different points in time, the span

of their post return stay varied from person to person. In spite of the fact that this study

could not ascertain the exact time of the disease occurrence (relied up on the time of

diagnosis) for each respondent, the reflection on the prevalence rate of chronic disease

morbidity in conjunction with the information on economic circumstances and the length

of post return phase would, definitely, complement the study.

BELOW Rs 20000

Rs 20000 AND ABOVE

170

Many other return emigrants were insured for accidents at the work place and they

had to access care for any other health problems by spending their hard earned money.

Since prompt medical care in the Gulf was primarily linked to ability to pay, a look at the

prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity in comparison with the return emigrants’

overseas income level is essential.

7.23. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Income from Employment Abroad

The overall mean income from employment abroad was worked out to be Rs 16,379

per month. Based on this estimation, Rs 20,000 was fixed, logically, as the benchmark to

distinguish between two groups of income recipients – below Rs 20, 000 income group

and, Rs 20, 000 and above income group. Chronic disease prevalence rate arrived at on

this basis revealed that the group with an average income of less than Rs 20, 000 per

month had a higher prevalence rate (356/1000) compared to the prevalence rate

(318/1000) of the other group with a monthly mean income of Rs 20, 000 and above (see

figure 7.13)

Figure 7.13:Prevalence Rate of CDM by Monthly Income from Employment Abroad

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.24. Chronic Disease Morbidity by duration of Post Return Phase

Subsequent to the eventual return from the Gulf, all the respondents were staying with

their relatives at home. As each individual had returned at different points in time, the span

of their post return stay varied from person to person. In spite of the fact that this study

could not ascertain the exact time of the disease occurrence (relied up on the time of

diagnosis) for each respondent, the reflection on the prevalence rate of chronic disease

morbidity in conjunction with the information on economic circumstances and the length

of post return phase would, definitely, complement the study.

318

170

Many other return emigrants were insured for accidents at the work place and they

had to access care for any other health problems by spending their hard earned money.

Since prompt medical care in the Gulf was primarily linked to ability to pay, a look at the

prevalence rate of chronic disease morbidity in comparison with the return emigrants’

overseas income level is essential.

7.23. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Income from Employment Abroad

The overall mean income from employment abroad was worked out to be Rs 16,379

per month. Based on this estimation, Rs 20,000 was fixed, logically, as the benchmark to

distinguish between two groups of income recipients – below Rs 20, 000 income group

and, Rs 20, 000 and above income group. Chronic disease prevalence rate arrived at on

this basis revealed that the group with an average income of less than Rs 20, 000 per

month had a higher prevalence rate (356/1000) compared to the prevalence rate

(318/1000) of the other group with a monthly mean income of Rs 20, 000 and above (see

figure 7.13)

Figure 7.13:Prevalence Rate of CDM by Monthly Income from Employment Abroad

(Per 1000 Return Emigrants)

Source: Sample Survey

7.24. Chronic Disease Morbidity by duration of Post Return Phase

Subsequent to the eventual return from the Gulf, all the respondents were staying with

their relatives at home. As each individual had returned at different points in time, the span

of their post return stay varied from person to person. In spite of the fact that this study

could not ascertain the exact time of the disease occurrence (relied up on the time of

diagnosis) for each respondent, the reflection on the prevalence rate of chronic disease

morbidity in conjunction with the information on economic circumstances and the length

of post return phase would, definitely, complement the study.

356

171

Table 7.16: Prevalence Rate of CDM by duration of Post Return Phase

Period of PostReturn Phase(Years)

ReturnEmigrants

Return Emigrantswith Chronic Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)Below 10 312 95 304

10 - 20 34 20 588

20 and Above 14 09 642

Overall 360 124 344Source: Sample Survey

The prevalence rate increased, obviously, with the extent of post return phase (see

table 7.16). This observed association might, in part, be due to the effect of ageing but, the

activity that every return emigrant had to pursue during the post return phase, and of

course its length, also could have influenced the current state of their health.

7.25. Chronic Disease Morbidity by Post Return Employment Status

On the basis of the current employment status, the return emigrants were classified

into ‘employed’ and ‘unemployed’. The ‘employed’ group consists of both wage/salary

employed and the self employed. The prevalence rate was slightly higher among the

‘unemployed’ (348/1000) relative to the rate (343/1000) among ‘employed’ (see table

7.17).

Table 7.17: Prevalence Rate of CDM by Post Return Employment Status

Post Return ActivityStatus

ReturnEmigrants

Return Emigrantswith Chronic

Disease

PrevalenceRate

(per 1000)

Unemployed 115 40 348

Employed 245 84 343

Overall 360 124 344

Source: Sample Survey

An unemployed person would, categorically, be a person with no stable income and

would, therefore, be more constrained in meeting health expenditure. The purchasing

power, from the current income, of the ‘unemployed’ would be zero, unless they are

endowed with other sources of income. This, unequivocally, imply that their recurring

health expenditure would definitely lead to a further deterioration in the already fallen

172

standard of living. The association shown in the above table did not offer any vital

information, other than the scale of morbidity prevalence, to arrive at a valid inference on

the ability of the ‘employed’ in meeting health care costs.

A closer look at the table (table 7.17) reveals another crucial, at the same time

deceptive, information regarding the employment status of the return emigrants with

chronic disease morbidity. It could be observed that only thirty two per cent (40/124) of

the respondents with morbidity remained unemployed and this proportion was somewhat

equal to the overall unemployment rate (31.94 per cent or (115/360) among the

respondents in the sample. This would lead to a false interpretation of the association

between chronic disease morbidity and employment status, without telling us anything

about the purchasing power of the ‘employed’ respondents with morbidity in the health

service market. The current income background of the chronically ill respondents would,

therefore, be a more fundamental aspect for evaluating their ability to sustain the standard

of living in the long run.

7.26. Current Income from Employment of the Return Emigrants with ChronicDiseases

The current income from employment, in the absence of regular income from any

other sources including accumulated financial assets, would be the sole source of

financing the recurring or intermittent health expenditure of individuals.

Figure 7.14:

Distribution of Return Emigrants with CDM by Current Monthly Income fromEmployment

Source: Sample Survey

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

BELOW 5000 5000 - 10000

NU

MBE

R O

F RE

TURN

EMIG

RAN

TS W

ITH

CH

RON

ICD

ISEA

SE M

ORB

IDIT

Y

172

standard of living. The association shown in the above table did not offer any vital

information, other than the scale of morbidity prevalence, to arrive at a valid inference on

the ability of the ‘employed’ in meeting health care costs.

A closer look at the table (table 7.17) reveals another crucial, at the same time

deceptive, information regarding the employment status of the return emigrants with

chronic disease morbidity. It could be observed that only thirty two per cent (40/124) of

the respondents with morbidity remained unemployed and this proportion was somewhat

equal to the overall unemployment rate (31.94 per cent or (115/360) among the

respondents in the sample. This would lead to a false interpretation of the association

between chronic disease morbidity and employment status, without telling us anything

about the purchasing power of the ‘employed’ respondents with morbidity in the health

service market. The current income background of the chronically ill respondents would,

therefore, be a more fundamental aspect for evaluating their ability to sustain the standard

of living in the long run.

7.26. Current Income from Employment of the Return Emigrants with ChronicDiseases

The current income from employment, in the absence of regular income from any

other sources including accumulated financial assets, would be the sole source of

financing the recurring or intermittent health expenditure of individuals.

Figure 7.14:

Distribution of Return Emigrants with CDM by Current Monthly Income fromEmployment

Source: Sample Survey

5000 - 10000 10000 - 15000 15000 - 20000 20000 ANDABOVE

CURRENT INCOME FROM EMPLOYMENT

172

standard of living. The association shown in the above table did not offer any vital

information, other than the scale of morbidity prevalence, to arrive at a valid inference on

the ability of the ‘employed’ in meeting health care costs.

A closer look at the table (table 7.17) reveals another crucial, at the same time

deceptive, information regarding the employment status of the return emigrants with

chronic disease morbidity. It could be observed that only thirty two per cent (40/124) of

the respondents with morbidity remained unemployed and this proportion was somewhat

equal to the overall unemployment rate (31.94 per cent or (115/360) among the

respondents in the sample. This would lead to a false interpretation of the association

between chronic disease morbidity and employment status, without telling us anything

about the purchasing power of the ‘employed’ respondents with morbidity in the health

service market. The current income background of the chronically ill respondents would,

therefore, be a more fundamental aspect for evaluating their ability to sustain the standard

of living in the long run.

7.26. Current Income from Employment of the Return Emigrants with ChronicDiseases

The current income from employment, in the absence of regular income from any

other sources including accumulated financial assets, would be the sole source of

financing the recurring or intermittent health expenditure of individuals.

Figure 7.14:

Distribution of Return Emigrants with CDM by Current Monthly Income fromEmployment

Source: Sample Survey

20000 ANDABOVE

173

The survey data showed that a greater majority of the return emigrants with

chronic diseases belonged to the low income background (see figure 7.14). This did not

imply that the chronic disease morbidity prevalence rates were higher for lower income

groups. It, basically, demonstrated the weak purchasing power, in terms of current income

from employment, of the respondents with chronic diseases.

7.27. Household Assets of the Return Emigrants with Chronic Diseases

An evaluation of the total value of the assets owned by the return emigrants, afflicted

with chronic diseases, was made to ascertain their overall economic background. The

assets included land, residential and other buildings, gold, diamond and other ornaments,

vehicles, fixed deposits, other investments and savings, home appliances and other assets.

Based on the assessment, four asset classes were formed.

Figure 7.15:Return Emigrants with CDM by the Total Value of Household Assets

(Value of Assets in Rupees Lakhs)

Source: Sample Survey

As shown in the figure (see figure 7.15), majority of the CDM inflicted return

emigrants belonged to the lower asset groups. It might lead to a wrong connotation that the

morbidity prevalence rates were higher in the least wealthy groups. In fact, this was not so;

the figure did not represent any association but rather reflect the economic background of

respondents suffering from chronic diseases. The fundamental issue that emerged from the

evaluation of the current income and overall economic background of the disease affected

return emigrants was related to their capability in maintaining, at least, the present

standard of living in the long run, given the recurring and intermittent expenditures on

health care.

0

20

40

60

80

BELOW 25 25 - 50 50 - 75 75 AND ABOVENU

MBE

R O

F RE

TURN

EMIG

RAN

TS W

ITH

CD

M

ASSET GROUP

174

7.28. Recurring Health Expenditure per Month

The return emigrants with chronic diseases continued to spend, regularly, on health

care. As much as thirty six per cent of them spent between Rs 500 and Rs 1000 per month

(see table 7.18). Another twenty one per cent spent between Rs 1000 and Rs 1500 while

more than a quarter of them spent less than Rs 500 per month. Merely nine per cent

incurred expenditure amounting to more than Rs 2000 per month. The recurring health

expenditure included cost of drugs, doctor fees, charges on pathological and other tests

and travel expenses.

Table 7.18: Distribution of Return Emigrants with CMD by Monthly HealthExpenditure

HealthExpenditure/Month

(Rs)

ReturnEmigrants

Return EmigrantsPer cent

CumulativePer cent

Below 500 33 26.6 26.6

500 – 1000 44 35.5 62.1

1000 – 1500 26 21.0 83.1

1500 – 2000 10 08.0 91.1

2000 – 2500 09 07.3 98.4

2500 and Above 02 01.6 100

Total 124 100 100

Source: Sample Survey

7.29. Expenditure on Admitted Medical Treatment

Besides the recurring expenditures, thirty two per cent of the disease affected return

emigrants spent Rs 64208, on average, for admitted medical treatment, during the one year

period prior to the survey. The expenses included cost of admission ticket, room rent/bed

rent, cost of medicine/materials, laboratory charges, charges of special examination like

scanning, fee for surgery, cost of food, bystander’s/helper’s expenses and miscellaneous

expenses.

Many of the disease inflicted respondents, who underwent admitted treatment, did not

have regular monthly income as they were unemployed (see table 7.19). Only fifty nine

per cent of them were employed either in wage/salary employment or self employment.

175

The cost of admitted treatment along with recurring expenses made many return emigrants

to take recourse to some other sources of finance. In fact, even without admitted treatment,

some of them found it very hard to meet health expenditure from regular income.

Table 7.19: Distribution of Return Emigrants with CMD who Underwent AdmittedTreatment during the Last Year by Monthly Income from Employment

Monthly Income fromEmployment (Rs)

ReturnEmigrants

Return EmigrantsPer cent

CumulativePer cent

Unemployed 16 41.0 41.0

Below 5000 02 05.1 46.2

5000 – 10000 12 30.8 77.0

10000 – 15000 06 15.4 92.4

15000 – 20000 02 05.1 97.5

20000 and Above 01 02.5 100

Total 39 100 100Source: Sample Survey

7.30. Sources of Financing Health Expenditure

Insufficiency of current income, to meet health expenditure, compelled thirty eight

per cent of the return emigrants with diseases to look for alternative sources (see table

7.20). More than twenty three per cent of them were drawing from their past accumulated

savings. Eight percent pledged their gold ornaments while another four per cent had their

land either sold or mortgaged.

Table 7.20: Distribution of Return Emigrants with CMD by the Sources ofFinancing Health Expenditure

Sources of Financing ReturnEmigrants

Return EmigrantsPer cent

Current Income 77 62.1Savings 29 23.4

Mortgage of Gold 10 08.1Mortgage of Land 3 02.4

Sale of Land 2 01.6Other Borrowings 3 02.4

Total 124 100Source: Sample Survey

176

The financial burden that the return emigrants endured on account of recurring and

intermittent health expenditures was, in fact, the direct cost of ill health. The indirect costs

of debilitating health usually take many forms. It can be in the form of preventing a person

from pursuing productive employment or if employed, not allowing him to reap the full

benefits from it. Also, the household members might face the inconvenience owing to the

ill health of a dear one.

An examination of some of these issues rendered startling results that showed wide

disparity, in many fronts, between the return emigrants with chronic diseases and those

without diseases.

7.31. Return Emigrants with Chronic Diseases against Return Emigrants

without DiseasesThe return emigrants with chronic diseases (the first group) had an average duration