An Analysis of the Monetary Causes of the Great Depression

-

Upload

ricardo-diaz -

Category

Documents

-

view

11 -

download

0

description

Transcript of An Analysis of the Monetary Causes of the Great Depression

65

An Analysis of the Monetary Causes of The Great Depression

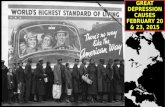

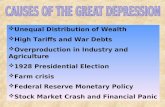

Of the myriad of explanations concerning the causes of The Great Depression of the 1930s, there remains today a minute amount of consensus among economists with regards to this. Despite the lack of concurrence, it is very clear that there were, in fact, multiple fundamental monetary weaknesses within the United States economy that left their domestic financial system susceptible to the volatile consequences of a poorly managed and vitally flawed financial and economic structure. It was due to these monetary factors that partially created and wholly triggered the collapse witnessed in 1929 in the United States. The over-reliance on credit in the United States, followed by the stock market crash of 1929, coupled with a fundamentally weak banking system and incompetence on the part of the Federal Reserve that ultimately set in motion and exacerbated the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In the years prior to the Great Depression, the American agricultural sector and American household were extremely dependent on credit, creating a financial landscape highly vulnerable to the wildfire of collapse. The agricultural sector in the United States was an infamous abuser of the credit drug during the pre-crash period, and [f]armers, a much more important segment of the American population than they are today, were deeply in debt their land mortgaged and their prices inadequate to allow them any escape. Despite low output prices for farmers, they continued to seek more credit from small banks to finance additional output, and [s]mall banksespecially those tied to the agricultural economywere in constant trouble throughout the 1920s; there was a steady stream of bank failures among these institutions. Guilty of providing unsustainable credit, many small banks failed due to farmers in the agricultural sector defaulting on loans they were provided. The extent to which these poor credit decisions were made created a dangerous subculture of cheap credit provided to almost anyone, even if debtors (such as the famers mentioned above) were unable to repay them. The very purpose of modern-day credit checks is to lessen the risk of default by a debtor to a potential creditor, and is the very reason only certain individuals or firms should be granted credit. Furthermore, despite falling prices in agricultural, rising prices of stocks in the American stock market were occurring at the same time. This speculation was appealing to the experienced and inexperienced investor alike, since stock prices seemed to be going nowhere but up. However, [w]hat made this speculative fever particularly dangerous was not the rising prices of the stocks; in fact, stock prices were not really out of line with the values of the companies. The danger arose from new investors who could not really afford the stocks they were buying. Seduced by the promise of permanent growth, they bought stocks on unsustainable credit. Just as banks were granting credit to farmers, they were also granting credit to investors to purchase stocks whose prices were expected to rise and keep on rising, sometimes with a down payment of a mere 10 percent of the purchase price, leaving creditors to these investors susceptible to default should stock prices begin to fall. This foolish overreliance on credit created a vulnerable investment atmosphere that normalized investing with unsustainable loans that were likely to never be repaid.

The vulnerability of this flawed system was put on display at the national level with the stock market crash of 1929, sending optimistic speculation in reverse and ultimately curtailing investment and household expenditures within the United States economy. While it is generally agreed upon that the stock market crash of 1929 did not altogether cause the Great Depression, it created a widespread panic among investors and households due to the fact that [n]o other country had a stock market panic of the magnitude of the American one, in large part because no other country had experienced the euphoric run-up of stock prices that sucked large numbers of Americans, from very different backgrounds, into financial speculation. The sheer enormity of the increase in stock prices attracted a vast array of different Americans into the trading of stocks, and the effects of the crash were felt by an enormously large set of individuals. This caused investors and households to start strategizing and deferring expenditures due to widespread fear of the economic climate worsening. For investors, [a] bursting stock market bubble has a depressive effect on investment because the destruction of entrepreneurial wealth inhibits the ability of entrepreneurs to buy capital. Also, an increase in the riskiness of entrepreneurs leads to a fall in investment because the rise in interest payments to banks cuts into their net worth. Clearly, the period of speculation following the crash of 1929 curtailed entrepreneurial investment due to a rising risk and lowering return on investment; the glory days of obtaining credit with little collateral were finally over. Similarly, in terms of the layman consumer, their prices fell 25 percent between 1929 and 1931, with wholesale prices falling 33 percent in the same time period. While entrepreneurs were deterred from investing during this time period, speculation among American households also curtailed consumer purchases due to the deflationary expectations expressed above. Since prices were falling and were expected to continue falling, there was little incentive for consumers to make these purchases. At the same time, due to their inability to procure any more credit for purchasing stocks or miscellaneous consumer durables, consumers were finally given the incentive to save instead of spend. This was detrimental to gross domestic product during this time, since [h]ouseholds' attempts to obtain more currency also induces them to cut back on consumption expenditures, which further depresses aggregate spending. Evidently, the financial system was in complete disarray due to the speculation caused by the crash of 1929 since consumers were saving money instead of spending it; all the while entrepreneurs lacked any real incentive to invest. This sort of double dipping in gross domestic product severely harmed the United States economy during the post-crash period.Finally, as briefly stated earlier, a fundamentally weak banking system coupled with unprecedented negligence on the part of the Federal Reserve was the final flaw in a mediocre United States economy, ultimately worsening the length and magnitude of the Great Depression. While nary a free market economist would argue that too much competition is a bad thing, indeed, it was too much competition among the banking industry in the United States that contributed to the financial instability of the 1920s and 1930s. In an effort to remain competitive, many large banks that were overextending themselves, making excessive loans, leaving themselves unprepared to deal with sudden, heavy demands from depositors. As discussed earlier, too many unsustainable loans granted to farmers and investors lowered bank reserves to a significant degree. This made many banks prone to bank runs which few were ready for, as [o]ver 9,000 banks either went bankrupt or suspended operations to avoid bankruptcy between 1930 and 1933. Depositors lost 2.5 billion dollars in deposits. The rampant bank failures occurring after the crash of 1929, wiped out a large portion of the savings and deposits of American households that would have served as new investment opportunities for entrepreneurs. This Achilles' heel of the United States banking system could have been partially, if not entirely, avoided given a more rigid set of banking standards that all banks would have adhered to. While the responsibility of loans being repaid is wholly on the debtor, there also exists an obligation on the part of the creditor to make financially responsible lending decisions to potential recipients of loans instead of being imprudent and financially reckless with handing out credit. It would, however, be incorrect to place the blame of this entirely on the large set of small, unregulated banks of the 1920s. Low interest rates issued by the Federal Reserve during the boom of the 1920s made credit much easier to acquire for those who would be unable to repay these loans once interest rates rose. Not only that, following the crash [t]hey responded to the economic wreckage around them and responded by raising interest rates so as to protect the value of the dollar and the solvency of the Federal Reserve Bank itself. Despite the American financial system being in near ruins, the Federal Reserve opting to raise interest rates further decreased any instance of investment since very few investors could afford new loans at higher interest rates. This rising of interest rates during a time of complete and utter economic disarray brought investment, a vital component of United States gross domestic product, to a near standstill. The Federal Reserves ineptitude to control outrageous loans being granted in a weak banking system, and the subsequent tightening of credit by raising interest rates ultimately halted the heartbeat of the United States financial system, worsening the effects of the Great Depression.

Evidently, the four horsemen of an economy too dependent on credit, a collapse of the stock market in 1929, a fundamentally flawed banking system and general incompetence by the Federal Reserve started and worsened the Great Depression of the 1930s. Despite the lack of agreement among economists as to the true, deep-seeded causes of the Great Depression, it is undeniable that the mistakes mentioned above that were made during this time period serve as warnings for modern day monetary policy makers to avoid similar financial disasters in the future. Only time will tell if these crucially important financial errors are truly taken to heart or not.Works Cited

Bordo, Michael, and Harold James. "The Great Depression Analogy." Financial History Review 17 (2010): 128. Cambridge Journals Online. Web. October 27, 2011.

Brinkley, Alan. "The Great Depression." The Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville 30.2 (2009): 107, 109, 111, 112, 114. Project MUSE. Web. October 27, 2011.

Christiano, Lawrence, Roberto Motto, and Massimo Rostagno. "The Great Depression and the Friedman-Schwartz Hypothesis." Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 35.6 (2003): 1121, 1131. Web. October 27, 2011. Brinkley, Alan. "The Great Depression." The Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville 30.2 (2009): 109. Project MUSE. Web. October 27, 2011.

Ibid.

Brinkley 111

Ibid.

Bordo, Michael, and Harold James. "The Great Depression Analogy." Financial History Review 17 (2010): 128. Cambridge Journals Online. Web. October 27, 2011.

Christiano, Lawrence, Roberto Motto, and Massimo Rostagno. "The Great Depression and the Friedman-Schwartz Hypothesis." Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 35.6 (2003): 1131. Web. October 27, 2011.

Brinkley 107

Christiano, et al. 1121

Brinkley 109

Brinkley 112

Brinkley 114

6