Amos Oz Style

-

Upload

amiller1987 -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of Amos Oz Style

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

1/20

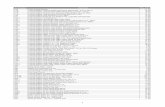

Modern Language Studies

Language and Reality in the Prose of Amos OzAuthor(s): Avraham BalabanSource: Modern Language Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 79-97Published by: Modern Language StudiesStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3194829

Accessed: 24/03/2010 06:28

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mls.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Modern Language Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toModern

Language Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3194829?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mlshttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mlshttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/3194829?origin=JSTOR-pdf -

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

2/20

LanguagendRealitynthe Proseof AmosOzAvrahamBalaban

1. IntroductionIn an interviewgivenin the late 1970s,Amos Oz talkedabouttheeffect of the books hehas loved:"Ifthe booksIhave loved didsomethingto me . . . they broke all the distinctions for me, floor and window,window and door, positiveand negative,good and evil. They openedup the world in frontof me with all its unendingcomplexity,with alltheabundance t has to offer"(1978).Speakingaboutthe"greatbooks,"and about the sought-after ffect of hisown books,Oz did not mentionanythematic ssues,butratherdelineateda generalattitude owardstheworld, its complexity and abundance.Implicitly Oz touches in thisansweruponone of thefundamental ifficultieshehad tocopewithfromthe very beginningof his literarycareer. The world is depicted in hiswork as a volatile, complex existence, in which contradictory orcesmetamorphosize nto each other and coexist with each other throughstruggle and reconciliation.Language,in contrast,consists of fixed,unequivocal igns,whosemeaningsare builtby meansof differencesanddistinctions.Moreover,heforcesthatattractOz'sprotagonists reprimalforces, preculturaland prelingual.Oz's charactersare spellbound byexperientialrealms where holiness and sin, light and darkness,flowinseparably.How is it possible,then,to use language,which is built ondichotomies,which separatesand scatters ts references,to describe aprimordialworld,anexistencewithoutdistinctions nddifferentiations?Anexamination f thestory"BeforeHisTime," heearliest toryof Oz'sfirstbook, revealsthatthe tensionbetween the natureof languageandthe natureof the worldhasshapedtheproseof Oz, itsstyleandstructure,from its inception.The solutionsto this issue that Oz found in writing"BeforeHisTime"would servehimthroughouthis careerto its presentphase.In thisarticleI discussthe severaltactics Oz exercises n "BeforeHisTime" n order to bridgethe gapbetweenlanguageandreality.Thefinal part of the article draws some conclusions concerning Oz'ssubsequentwork.2. Theprimevalwaters"BeforeHis Time"is Amos Oz's thirdstory (1962),and the firstto be included laterin his firstbook, Where the JackalsHowl (1965).'In manyrespectsthisstoryservesas a model for Oz'ssubsequentwork,his shortstoriesas well as hisnovels.2Beforeelaboratingon the variousmeans Oz has used to overcome the fundamentaldifferencebetweenlanguageand his protagonist's omplicatedexistence,it is necessarytobrieflydescribethe mainthemes of the story.2.1 Oz's comments on the work of Berdyczewski,whom he describesas his "familyrelative,"offer an illuminatingnsightinto the world of

79

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

3/20

"BeforeHis Time": "Whencoming to write a story his attitudewassomewhatskeptical.That s,peopleindeedhold allsortsof opinions,yetthese opinionsare no more thana restrainedand dignifiedversionofprimalforces, justas a domestic dog is merelythe tamed descendentof the wild wolf. And when the reinsbecome undonethedog willagainbecome the wolf-only then do Berdyczewski's toriesreachtheir truenature"1979,pp. 30-31).Ashis essential hemeis thoseprimeval orces,Berdyczewskidid not bother to bestow a psychologicalcompletenesstohisprotagonists:Itwas neitherpsychologynor deology,butdifferenttopics altogetherwhich interestedhim .... His centerof gravitywaselsewhere.Often, he created his protagonistsnot as men of flesh andblood but as earthlyrepresentatives f hiddenpowersand of the forcesof nature.And thus, Berdyczewski's tories are filled with demigods,devils, demons, and angels of destruction"(p. 31). This article isundoubtedlyOz's best descriptionof his own work. The notionthatthe"dog is merely the tamed descendent of the wild wolf" is expresslyconveyed in "BeforeHis Time"(p. 73. See below). Indeed, the themeof this story, like that of Berdyczewski'swork, centers around theprimordialorcesthrobbingwithin hehumanpsyche,andit,too,is filledwith"demigods,devils,demons,andangelsof destruction."2.2 The greatinterestOz displays n the primeval orceswhich rule thesoul and the universe s alreadyapparent n his first two stories.3 n thestory"PurpleCoast" 1962),whichpreceded"BeforeHisTime,"onecanclearlyperceivethisthemethrough heallegorical eil.Thetale describesa groupof travelers pendingtheir ives in a never-endingourneyuponthe ocean. Only the narratordoes not take part in the ship'slife ofcomplacency and abandonment.Each morninghe sees strangeillu-sions-islands, purpleshores,tall palms-and these visions disturbhispeace. He seeks to bring the news of these islands' existence to theattentionof hisfellow travelers, ndthesetidingsarea call forrebellion.However,his attemptedmutinyfails. The masses of passengers lee totheir cabins and the narrators declareddead by the ship'scaptain.Atthecaptain'sorderhe is castintothe sea to be buried n a nauticalgrave.What s the meaningof thisstrange ale? What s thesignificanceof the characters orrowedfromBabylonian nd Greekmythology,whoinhabit heship'sdeck?Inattemptingo exposethe humanconditionandthe forceswhichdrivepeople,Oz turned o theprimordialwaters,fromwhich the world itselfwas createdaccording ovarious raditionalmyths.The ocean'swatersin thisstoryare full of instinctsand desires.This isevidentalready nthestory'sopening ines,"Atnight heshipmovedoverthe ocean like a caressover the warm sea.... The passionsof the seapenetrated nto the shipand hoveredover its decks like a thin mist"(p.202[inBalaban,1986]).Thepowerfulgenerativeorcesthatresidewithinthe ocean arepersonifiedby Dita, the beloved of both the captainandthe narrator.Dita, whose name is a shortenedform of Aphrodite,theGreekgoddessof love, is describedthroughouthestoryin termsof theocean waters.In sharpcontrast o the variousmythsof creation, he primordial80

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

4/20

waters, he monsterof thedepths,areby no meanssubdued nOz'sstory.This theme is expressedthroughthe figure of Mordu,an allusiontoMarduk, he creatorof the universe n Babylonianmythology.Mordu'sfearsof theopeningof thechimneysof theheavens,of anew flood,referto themythologicalale:aftersplittingTiamatandcreating hefirmamentwithhalf of herbody, Marduk tationedguards o preventTiamatfromreleasingherwaters.Fromthe story "PurpleCoast" t becomes evidentthat the guardsfailedin theirassignment.The ocean is portrayedas theflood waters(manybiblical allusionsdepict the shipand its passengersas the Ark of Noah with its manyanimalson board),and Mordufearsanother lood. Inotherwords,Tiamatdid notperish-she is aspowerfulas ever.Inall,thestory depictstwo elements,two principlesof existence:on theonehand,there s thefeminineelement,symbolizedby theocean,the ring,darknessand the unconscious;on the otherhand, thereis themasculine element symbolized by land, a straight line, light,consciousness.These two elements are not of comparablestrengthsorlevels. The ocean is portrayedas authenticreality,full of vitalityanddesires. The land is sproutingforth from this ocean and is still underconstant hreatof being flooded by itswaters.Furthermore,he landinthisstory smerelya mirage,unverified,andperceivedby one manonly.The implicationsof thisplot are clear:consciousness,he lit areasof thesoul, grew from the darkdepth of the unconscious,and its existenceisstill ragile,uncertain,ikeanew island hatcanbe flooded atanymomentonce againby the ocean.In hissearchfor theprimevaloriginsof thesoul,Oz turned nthisinstance o themythof creation, o theprimalstrugglebetween Mardukand Tiamat. Severalallusions o the storyalso refer to the struggleofcreationnGreekmythology(thename of thecaptain'sdog isTitan,etc.).Thissearch o unveil heprimeval orces of thepsycheand of the universewill appear throughoutOz's work.LikeBerdyczewski,Oz gives up the"psychology" f his characters, nd tries to uncover the primalroots ofthe human soul.Time and againwaterwill appearas a centralsymbolin his writings, representing he deep primevalwaters, Tiamat,or inJungian erms,the collective unconscious.42.3 It is quite clear that the theme of "BeforeHis Time"also concernstheunderlying oundations agingwithinthe soul. Oz evenuses here themain symbols of "PurpleCoast." The kibbutz is illustratedas anilluminatedsland,whereas the jackalsand the darknessare likened towaves of a sea threatening o flood the island. The drama of creation,the battle between Mardukand Tiamat,is expressedin thisstoryas astrugglebetween God andSatan,OsirisandSeth,manandjackal.3. Thekibbutz:Mythis Reality"BeforeHis Time"revolves aroundthe lastnightof Samsonthebull and of Dov Sirkin,a former kibbutz member who now lives inJerusalem.Samsonhaslost hisfertilityafterbeingbittenby a madjackaland has been condemned to the slaughter.Dov Sirkinsits in his room

81

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

5/20

designing,as he often does, a splendidworld of Titanicproportions.During heeveninghe hears ootstepsapproaching isdoor,andimaginesthattheadvancing trangers his son Ehud who fellyearsagoinareprisalraid of the IsraeliArmy.In the past, on the kibbutz,Dov had ragedawar on the jackals hatprowledoutsidethe gatesof the kibbutz.In hislastmoments,as the criesof thejackalspenetratentohishouse,he admitsthatin the waragainst hejackals, t is thejackalswho laugh ast.3.1 The storyopens in a 'spargamus,'he death of the protagonistandthe scatteringof the pieces of his flesh:"Thebull was warm and strongon thenightof hisdeath.In thenight,Samson he bull was slaughtered.Early nthemorning,before the five o'clockmilking,a meattrader romNazareth ameandtookhimawayinagreytender.Portions f his carcasswerehungon rustyhooksin the butchershopsat Nazareth.The ringingof churchbells rouseddroves of flies to attackthe bull's lesh,swarminguponit andexactinga green revenge" p. 59).Thesimilarityo the storyof Osiris, dentifiedwith the bull-deityApis,is apparent:ike Osiris, hegod of fertility,Samsonwas the matingbull and he too fell victim toforcesrepresentinghe primalwaters.5Osiriswas slaughteredby Seth,hisbrother, epresentinghe cruelsea. Thebull was bittenby thejackals,described nthestoryas watersof a darksea.Moreover, hejackals, ikeSeth,are referred o later nthestoryas "acursedbrother."The factthatuponhis deathSamsonis describedas returning o a fetal position (p.61) calls to mindthe cyclicnatureof Osiris' ife.Typicalof his style, Oz does not contenthimselfwith only onemythologicalale as abackgroundor thestory.Thevile fliesthatswarmuponthe bull's lesh arenotportrayedas fliesmerelyseekingto appeasetheirhunger. They exact a "greenrevenge"from the dead bull. Whatis the functionof thisanthropomorphism?n the followingsentencesofthe storythe reader earnsthat the bull'shide is destinedto be used forholy pictures depicting the story of Jesus. In this context one cannotoverlookChristian ymbolismin which the fly representsevil and sin(Ferguson,1961, p. 12). One may furthernote that the founders ofChristianity egarded hebullas a symbolof Christ(Ibid, p. 22).The confrontationbetween the bull's flesh and the flies wasprecededby a confrontation etweenthebull andthejackals.Thejackalsembody the primevalwatersthatgrew flesh and blood and wailings.6These struggleshave two parallels n the humansphere:the war Dovconductsagainstthe jackalsand the confrontationbetween Jews andArabs.It is no coincidencethat Arabs rom Nazarethbuy thebull'shideandflesh. Andlikewise,Ehud,Dov'sson,isdescribed nlanguagewhichclearlyalludes to the descriptionof the bull (p. 62), whose fate Ehudshares.Theyoungcommander alls nabattlewiththeArabs.Thejackalstearingathisdead fleshfinishoff whatthe Arabsbegan.Themythicalelementof thestoryhas aJewishaspectaswell. Thedescriptionsof Dov as the "ruler" f the orchards(p. 63) and as the"masterof the orchards" p. 64) cast him as a godly figure,as Adam.However,the depictionof hismotivesto leave thekibbutz,"Andhe setout to roam the landand leave his fingerprint n it"(p. 62), cannotbut82

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

6/20

recallSatan who encountersGod'schildrenas he "roams he land andwandersin it" (Job, 1:7, 2:2). Furthermore, everal traditionsportrayLilithas thewife of Adam,whileothersportrayher as Satan'swife. Andindeed, Zeshka,Dov's wife, is portrayedas Lilith.LikeLilith,Zeshka'sdomain is the night,and like her, she is picturedas an owl (p. 61). Inthe second version of the storyOz added two pointswhich tie Zeshkato Lilith.Her attitude owardschildren(1976,p. 66-7,EE 68) resemblesLilith,whose hostility owards them is a distinctive eature.Second,herresponse,as she hearsthe lasciviouswailingsof the jackals,alludeto theerotic licentiousness f Lilith(p. 67, EE 69).3.1.1 The mythicalnature of its characters s an essentialaspectof thestory.One of its centralthemesis the immensepower of the primevalwaters,which thwartevery attemptto alter the forceshidingin them.The fact that the kibbutzmembers,the typicalbearers of cultureandenlightenment, mbody centralcharacteristicshattie them to primevalmythicalcharacters olidly establishes he strengthof these primordialforces. This unconquerablepermanenceis establishedby means ofseveralother devices in the story. Wordstaken from the chaptersofcreationin the Bible lend to Dov a primevaldimension.His room isdescribedas an"abyss": Anda blackchandelier loats above theabyss"(p. 65). Oz uses here the Hebrew word 'tohu,'which appearsin theopeningsentencesof Genesis.The sameword illustratesDov'sdrawings(p. 68). At night"a silentcrust" s stretchedon Dov'sstreet,"anda bluemistroseup fromtheopeningsof thesewers" p.65).Thisimagealludesto anotherdescription rom Genesis:"But herewent up a mistfrom theearth,andwateredthe whole face of theground"Genesis2:6).The word"crust" ointsto a fermenting, everishworld,which at thismoment iscoveredin a thinpeel. In Dov's roomthe borderbetween the livingandthe inanimate,between manand beast is completelyblurred.The roomis filled with a "herdof furniturebellowingwith thickvoices"(p. 65),thetableisheldupby thelegsof Dinosaurandthebranchesof the cactusare"twistedsnakes."The sentence whichsealsthispicture-"and in thecenter, at an ornate desk with gold and silver fittings-the man"-portraysDov as the core of thischaoticexistence.Dov's last words are also dedicated to the unvanquishableprimitiveforces of nature:"When he kibbutz was founded,Ehud,wetrulyset out to establisha new order,untilthingsshriekedout thattheycannot be set right.I said, there arethingsthat man can do if he wantsthem withallhisheart.But I did notknowthatthere s nopointinleavinga fingerprinton the water"(p. 74). In the second version of the storythisissue is set out even more clearly:"When he kibbutzwas foundedwe believed thatwe reallycould turn over a new leaf, but thesethingsshriekedoutthattheycannotbe setrightandtheyshouldbe left as theyhave been sincethe beginningof time"(p. 83, EE 89).It becomes clear thatthe dark,jackal-likeocean, gave rise fromits midstan illuminated sland.Whereas he jackals n thisstoryare therepresentativesf thedarkwaters,the kibbutz s the clearrepresentativeof culture.The kibbutzwasfoundedas a framework ncompassing very

83

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

7/20

sphere of man's activities. This revolutionaryorganization whichdetermines or hismembers heirdailyroutine, heirplaceof work,theirsocial functionsetc., was not an end in itself,but only a startingpoint.This social structure was established with the hope of changingcompletelytheJewishnature,or humannature,altogether.The foundersof the kibbutz were not satisfied with culture in its westernmanifestations.They soughtto create humanbeingsby the dictates ofthe Socialistdealswhichtheyheld:Asane and rationalman,freedfrominstinctsof greed and power; in short,a man drivenby his ideals andnot by his inbornnaturaldrives. Cognizantof the revolutionaryandpioneeringcharacterof their undertaking, he kibbutz memberssawthemselvesas a "group o set the worldright" p. 64). Dov's lastwordsexpose this ambition to "set right"the primeval forces ("butthingsshrieked out that they cannot be set right"), only to emphasize itscompletehelplessness n the face of these forces. The primevalwatersdestroyanyattemptto giveshapeto themor to imprinta markon them.Herein ies the maindifferencebetweenthe fateof thebulland the fateof Osiris.Osiris sa cyclic story.ThedeadOsirisrisesto life everyspring.His fall is but a necessary ntermediate tep to victory.7 n "BeforeHisTime"this resurrection s not achieved. The slaughteredbull will notreturn o life nor regainhis fertility.Ehud,who was "reaped" pp. 62,70), will not returnfrom his grave. Jesus, contrary o Christianbelief,failedcompletelyin his mission.Mortalsare as far as they alwayshavebeen fromsalvation.4. TowardsLanguageandBeyondCommentingon the workof Berdyczewski,Oz said:"Hewas a'thin' writer.... He did not bother to catch every nuance or to capturethe flow of things.... His center of gravity was elsewhere" (1979, p.31).Thesethoughtsarewelltakenasthey applytothestyleof Ozhimself.He, too, does not seek "tocapturethe flow of things," he continuousflow of experience, he abundanceof impressions ecorded n the mindfromboth internal ndexternal timuli.His centerof gravity s elsewhere:notinthe"flowof things"o which themoder humanbeingis exposed,but in the tenaciouspermanenceof the primalforceswithinthe humanpsyche.This center of gravityraisedcomplexstylisticproblemsfor Oz.Languageis tied inseparablyto consciousness.8 t charts the world,recording the perceptions known to consciousness. For primalexperienceswhich lie beyond consciousness, anguagedoes not havewords.9Theineptitudeof languageswell reflected n"BeforeHisTime."Thus,forexample,whentheprotagonistriesto definetheprimal orcesthe Kibbutz ounders riedto overcome,he findsonlythe generalword"things": Whenthe kibbutz was founded, Ehud, we trulyset out toestablisha new order,but thosethingsshrieked hatthey cannotbe setright" p. 74). The word "things"efershereto the primaldriveswhichthe foundersof the kibbutz sought to uproot. This word reappearscarrying he samemeaningthroughouthe storiesof WheretheJackalsHowl ("WhereheJackalsHowl,""AHollowStone,""StrangeFire,"and84

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

8/20

others).However,theword"thing"onveysaveryabstractmeaning hatsaysnothingabout the natureof theforceswithinthe soul.Theprimeval"things"renot"sayings"theHebrewword Oz useshere,"davar,"meansboth "a hing" nd"saying") utthe namelessprimevalbasic foundations.These "things"do not expressthemselvesin "sayings" ut in "shrieks"which cannot be phrasedin words. The protagonistof the storywhosketches ngreatdetaila wild andTitanicworlddiscovers heimpotenceof languagein the face of thisworld. In attempting o compensateforthisshortcoming,Oz is aided by the word "shrieked"which draws onvoices and feelings beyond words and ties the above sentence to the"licentioushrieking"n Dov Sirkin's oom (p. 65). The recurringuse ofthe word "thing"n the openinglinesof the following chapter("Likeathiefsome pale red thingarrivedand filtered ts fingersof light throughthe chinks n the Eastern hutter," . 74) alsoshows that the "things" rea fixed naturalphenomenon.104.1 Therecurring ppearanceof the word"thing"makesclear,asshown,that the word "things" efers to the eternal foundationsof the humanpsyche.Yet,that identificationdoes not contribute o the concretizationof the essence of those things,the nature of the hidden forces, or theconnectionsestablishedbetween them.In order to expressthe storyofthose "things"Oz turned,as we have seen, to the foundations, o thestruggleof Marduk ndTiamat,OsirisandSeth. To givea name to these"things,"o give them substanceand to blow life into them, he had toovercome one of the most essentialaspectsof language. Accordingtothe concept presented n "BeforeHis Time," n the primevalworld theforcesof sinandgrace,violentdestructivenessndfertilizingvitalityareinseparable.Language,nsharpcontrast, eflectsa conditionof splitting,separating.Saussure tronglymaintained hat the signsof languagearearbitrary nd do not derivetheirmeaningfromessentialqualities yingthem to theobjectstheydescribe.Instead, heirmeaning s derivedfromthe power of contrast,differentiatinghem from the othersymbolsoflanguage."In anguagethereareonly differences,"he concludes(1959,p. 120).Attheopeningof thisdiscourseSaussurepeaksof thetightbondbetween languageand consciousness:"Psychologicallyour thought-apartfrom its expression n words-is only a shapelessand indistinctmass.Philosophers nd linguistshave always agreedin recognizing hatwithout the help of signs we would be unable to make a clear-cut,consistentdistinctionbetween two ideas. Without anguage,thoughtisavague,unchartednebula" pp. 111-12).Thus, anguageexpressesa con-ditionof splitting,of creatingdistinctions ndsettingup partitions."The difficultythat stood before Oz, then, can be formulatedasfollows: How to portray a condition of primeval unity, in whichconflictingandcontradicting lementsbattle each other and fulfill eachotherat the same moment, by means of languagewhich is based ondivision and sharpdifferentiation?n order to overcome the stumblingblock of languageOz turned irst rom the"animalnman" o theanimalsthemselves (a bull, jackals,the vile flies, etc.). Thus he was able toaggrandizehe different orcesstrugglingwithin he soulof hischaracters

85

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

9/20

and to concretize those forces. Second, he created a world in whichstruggle and reconciliation go hand-in-hand, a world in which an objectis described as its complete opposite, on the one hand, and on the otherhand, sworn enemies are brothers in the soul. This dual structure of hos-tility and reconciliation is built by the story's plot, the composition of thevarious paragraphs, the metaphorical language, and many literarypatterns that stretch through the entire story.'2 In order to understandhow this structure is built, let us look at the first chapter of the story.It is a short chapter and I will present it here in its entirety:

The bull was warm and strongon the night of his death. In the nightSamsonthe bull was slaughtered.Earlyin the morning,before the fiveo'clockmilking,a meat trader rom Nazarethcame andtook himawayin a gray tender. Portions of his carcasswere hung on rustyhooks inthe butchershops of Nazareth.The ringingof the churchbells rouseddroves of vile flies to attack the bull's flesh, swarmingupon it andexactinga green revenge.Later,at eight o'clock in the morning,an old effendi arrived,carryinga transistor adio.He had come to buy Samson'shide. And allthe while Radio Ramallahpiped Americanmusic into the palm of hishand. A licentiousand wild tune was cast out and the church bellsaccompaniedit like cymbals.The tune ended-the transaction nded.The bull'shide was sold. Whatwill you do, O RashidEffendi, with thehide of Samson the mightybull?Ornaments will makeof it, work ofthe cunningworkman,souvenirs for rich lady tourists,parchmentofvariegatedpictures:here is the alleywaywhere Jesuslived, here is thecarpenter'sworkshop,Joseph nthemiddle,hereangelsarestrikingbellsto proclaimthe birth of the Saviour,and here is the Babe himself, hisforeheadshining ight.Everythingparchmentwork,the acme of art.RashidEffendi went to Zaim'scafe to spend the morningat thebackgammontable. In his righthand the radiowith its cheerfulmusic,andin his sackis packeda bundle of a steaminghide.A Nazarenewind,heavywithsmells,pluckedatthebell-clappersandthe cypresstreetop,stirring he hooksin thebutchershops,andtheflesh of the bull gave out a crimsonshriek(p. 59).

The compositional principle, on the surface, is a linearchronological one:"In the night, Samson the bull was slaughtered. Early in the morning... a meat trader from Nazareth came.... Later, at eight o'clock inthe morning, an old effendi arrived ...." Yet, this linearstructure concealsa complex structure of confrontations and conciliations.The firstparagraphcreates a drastic contrast between the vile fliesand the bull: the flies swarm upon him to exact revenge. We have seenpreviously, that the symbolic meaning of the bull and the flies conjuresup primeval struggles between God and Satan, between Osirisand Jesusand their enemies. This confrontation spreads its shadow over the entirechapter. In the following chapters this struggle is concretized in thehostility between bull and jackal, in the war between Israel and her Arabneighbors, and more. And yet, in this short chapter language not onlycreates a strong confrontation but also signs a peace treaty between theconflicting parties.86

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

10/20

The beginningof the paragraphdescribesthe effendi comingtobuy thebull'shide.Thetune heardfrom the radio n his hand s depictedas "wild and licentious,"adjectivesthatwould characterize he jackalslaterin the story.Thus,this tune is, apparently, he complete oppositeof the churchbells.Surprisingly, completeharmonyexistsbetweenthetwo. Thechurchbells,whosetask s to callthebelieversand tostrengthentheirbelief, mergewith the licentious uneas a festiveaccompaniment:"A licentious and wild tune was cast out and the church bellsaccompanied t likecymbals."Thisrelationshipmightdraw the reader'sattention o the fact thatalreadyin the firstparagraphof the storythechurch bells awakennot the church believersbut ratherthe vile flies,whichthenswarmuponthe bull's lesh andtake theirrevengeon it. Thebitterantagonismbetween the bull andthe vile fliesdevelopsin theendof thestoryintothe conflict betweenthe"obscenelyriotous ackals" ndthe festive message of the church bells (p. 74). However, in the firstparagraphsof the story the measured sound of the bells blend inthoroughlywith the dissoluteand wild tune,andeven awakensthe vileflies to takerevengeon the bull. To use a termparallel o the detailsofthe story,the authorestablisheshere a musical"chord":nsteadof play-ing one note from one stringhe createsa chord encompassingseveralstrings.'3By ways of oppositionand conciliation he chord ties detailsfrom different or even contradictingareas, and his meaning is builtthrough the connection that language creates between its severalreferences.The rivalrybetween the bull and the flies precedesthe strugglebetweenJewsandArabs.Indeed,thebull has lost hisfertilityafterbeingbittenby a jackaland ArabsfromNazarethgainhis fleshand hide. Yet,along with this confrontation ransactions re made between the rivalparties. A meat trader from Nazarethbuys the bull's flesh, and thetransaction oncerninghis hide is carriedon againstthe backgroundofthe mutualsound of the radioand the churchbells:"Thetune ended-the transaction nded."Moreover, he kibbutz'sbullis about to feed theArab inhabitantsof Nazareth,and its hide will be used for Christianornaments.In thissystemof confrontations nd conciliations hechurchplaysan importantrole. On the one hand, the church s supposedto be therepresentativeof culture,the diametricoppositionof the vile flies, thejackals and the licentious voices. Indeed, that is how the narratordescribesit in the finalparagraphof the story.On the otherhand,thechurchbelongsto the Arabside, which is paralleled n thisstoryto thejackals.Thus the church, ike Dov Sirkin,belongsto both worlds. Thisphenomenonexplains, among other things, the affinity between thechurchbells, the flies and the wild tune.It is easy to see that this techniqueis employed throughout hechapter.Each itempresented nit isreciprocally onnectedwithanotheritem: the transaction of the bull's hide is conducted against thebackgroundof the sounds of the radio and the churchbells; RashidEffendisitsin thecafe, holdinginhisrighthandtheradioand athisfeetthe hide of the dead bull;and a Nazarenebreezeplucksat the churches'

87

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

11/20

bells,the cypress' reetopsandthe bull'sflesh in thebutchershops.Themetonymical passages from one item to another,which create thesecatalogues, conceal a complicated system of contradictions andconciliations.Thus, the main thematicprincipleof the first chapterconsistsof two phases: irst,the creationof an acuteconfrontation;ndsecond, the establishmentof "chords" hat tie togetherthe combattingpartiesor theirmetaphoric epresentatives. hestruggle hatatfirstsightseems insolvable s accompaniedby clandestine econciliation.4.2 The firstchapterof "BeforeHisTime" s a thematicoverture o thestoryand,in general, o allof Oz'swork.It presentsa worldwhose axisis a primevalstrugglebetween mortalenemies.This primalconflict isaccompaniedby a series of devices which, paradoxically,reveal thekinship between the warring camps. These devices consist, in thecompletestory,of polyphonicconnections Dov Sirkin s paralledbothto a bull and to a jackal),different"chords,"ndmetaphoricalanguagewhichbestowshumanqualities o animalsandanimalqualities opeople.These devices reveal that the externalstrugglecovers a completelydifferentstruggle,the struggleof each side against tself. The partitionwhichstands nthe worlddoes not separateGod andSatan,heavenandearth,but existswithinthebattling orces themselves. ndeed,inthefinalchapterof the storyit becomes clear thatman and jackalareone, thatmanis his own mortalenemy.This conclusionclearlydemonstrateshatthe overt strugglecan never end in victory. The side which forevervanquishes ts enemy will irreparablywound sources of vitality andpowerthatlie latentwithinhimself.5. ManAgainstHimselfThe dual structureof conflict and conciliationenabled Oz todistinguishhebattling orces,to concretize heirpowerand theirnature,and,at the same time, to mergethem into a single unitaryexistence.Inthismanner,Oz overcamethe fact thatlanguageslices and scatters hecomplexityof existenceand presentsthe foundationsof existenceonlyin abstractand vague terms. These generalizationsdemand furtherelaboration.5.1 "Aneternalcurse s castbetween housedwellersandthose who livein mountainsand ravines.Sometimes,duringthe night,a plumphousedoghears he voice of his cursedbrother.The sounddoesnot come fromacross hefields.Thedog'senemydwellswithin.Fromthedepths tsendsout volleys of greenish aughter" p. 73). These sentencesconvey in acondensedand crystallized orm the worldviewimmersed n the story.True,the narrator ays, thereis progress n history,and a wild animalmay undergoa slow metamorphosis ndbecome domesticated.Yet,thelaw of conservationof energystillreignsin nature.The primalforcesdo not vanish. In new guise they sometimesreappearexertingtheirancientpower. This passage shifts the focus from the surfaceof theconflictto itsroots.Ozrecedesfrom thepresent nto the dawnof history,only to returnand portraythe presentfrom a new vantage point. It88

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

12/20

transpireshat the dog is but the youngerbrotherof the jackal.Thatis,alongwith an eternalenmitywhich exist between them,they alsosharea common blood whose strengthstands unmatched.Moreover,thecursed mountaindweller is also the plump house dweller himself, forhe continues o live in the"depths" f thetameddog. Ontheotherhand,it becomes evidentfromthisdescription hatthe dog is his own enemy,"aneternalcurseis castbetween"him and himself. As I arguedabove,thisis a centralthemein the storyand in all of Oz'swork.An object isitsown polar opposite.5.1.1 The main domainwhere this conditionis reflectedis, of course,in the human domain. The authoremphasizesthis fact, among otherthings,by depictingDov Sirkin s "housedweller" pp.64,71)inaparallelto thedog who was labelled"housedweller"and"housedog."No doubt,Dov concretizesthe contradictionembedded in the humancondition:he is Dov (a bearin Hebrew)anda man,a tamed bull and a jackal, hefoe of the bull.The contradictionwhich opens the story,between the bull andthefilthyflies,turns o a confrontation etween bullandjackal.Thejackaldies in thisstruggle,but he strikesat the fertilityof thebull,leadinghimto death:"Astrayjackalhad brokenintothe cattleshed andhad bittenSamsonin the leg. Samson killed him with a kick, but thatbite killedthe bull'spotency"(p. 60).Asis characteristic f theauthor'sworldview,Dov is paralleled o both the bull and the jackal, he bitter rivals.BothDov and the bull are "at the heightof theirpotency" (pp. 59, 67), andboth now suffer from an unseenmaladywhichbringsanuntimelydeathuponthem.Botharerestingat nightwithheadbowed (pp. 60,65), andboth, tiringof struggle,receive the "spasm"of death with a blessing("Finallyhespasmcame,and shookthe bull'sbody,"p. 61;"Finallyhespasm came, soft and compassionate,"p. 74). The bull representsaprimeval power that was tamed and locked behind bars. Thecontradictionnhisbeing bringsuponhisend. Not incidentallydoes thejackaldestroythesourceof thebull'svitalityandpower,hisfertility.Hiscastrationby the jackalonly concretizes he contradictorynatureof hislife.'4The bull sheds light on the forces hiddenwithinDov, as well ason the contradiction ubmerged nhisexistence: heneed to channel hemighty energythrobbingwithinhiminto a socialframework, estrainedand bridled. Another facet of this contradiction s the fact that thepowerful and generativeforces residingin him comprehendbase andevil drives as well. Thus,Dov Sirkin,who is paralleledto Samson thebull,is alsoanalogous o thejackals, he bull'skillers.The "lewdrejoicingvoices"of the jackals(p. 64) bringto mindDov's"rejoicingoice"(p.63)and thesignsof "licentiousness"nhisroom(p. 65). The "disordered"ounds of the jackals p. 64. Heb.:"i'rbuvya")is similar to the "disorder"which marks Dov's room (p. 65. Heb.:"maa'rbolet"). his room, like the world of the jackals(p. 64), reflectsanancientexistence,chaoticandunchanging.Thus, he evil andbaseness,the lewdness and impuritywhich the storyattributeso the jackalscanbe ascribed o Dov Sirkinaswell. Giventhisanalogy tis clearwhy Dov's

89

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

13/20

war againstthe jackals s doomed to failure.As mentioned,while stillon thekibbutz,Dov conducted a persistentbattleagainst hejackals p.62). With his "jackal"ide exposed, it becomes evident thatin fightingagainst hejackalsDov was fightingagainsthimself, ike the dog whosefoe dwellsunderhis skin.Dov tookpart nanideologicalmovementthatset itself the goal of changinghumannaturethrougha return o natureand workingthe land. The returnto naturematchedDov's characterperfectly,but italsobroughtalongwith it theloftyambition o "establisha new order,"orestrainheprimevaldrives nthesouland to forceuponthemsanity,reason,and balance. The return o natureawakenshiddenpowers in Dov (see for example the descriptionof his work in theorchards,p. 63). But along with returning o natureDov unknowinglyfights againstnature(in the form of the jackals),againsthimself.Thus,at the final scene of the storyDov admits that the kibbutzput forth anunattainable oal, and that the war he declaredagainstthe jackalswasdoomed: the jackalsareflesh of hisown flesh.By means of externalizingthe forces operating in Dov andillustratinghem as animals,Oz achieved severalprincipleobjectives.First, he enhanced the forces swirling within his protagonistandaccentuated heirunchanging,primalnature.The bull is "amightybull"(p. 59), "strongand ancient" p. 74). The jackalsalso "follow the leadof theirfathers,andnothing s changed" p. 64). Second,he singledoutthe differentpowersand concretized hem.Thebull,a traditionalymbolof the sun's ight,represents tremendouspowerthatwas restrained ndjoinedthe life withinthe fence. The jackal, n contrast, s the agent ofdarkness.He is impure, ewd and evil;though,as the representative fthe primevalwaters,the jackalhas, as we shallsee later,other sides aswell. The detaileddescriptionsof the animalsshift the storyfrom theallegoricalmodetothesymbolic.The readercan feel the heatof thebull'sbreathandblood, see hislegskickingattheproppings,or his taillashingathismuddybuttocks(p. 60). His deathis conveyed througha realisticdetailing, precise and accurate. The descriptionof the jackals s evenmore detailed(pp. 62, 64, 73, andmore).The thirdobjective s themostinteresting ne:aggrandizingheseforces and concretizingthem in order to achieve theirunity in Dov'scharacter,n which elementsof the bull and the jackalcoexist.Dov isportrayedas a mightyand powerfulcharactern which ApollinianandDionysianelements,sanityandinsanity,vie againsteach other.His soulis an arenafor a primevalstrugglebetweenGod and Satan.He belongsto the "illuminatedsland"of the kibbutz,yet one of his feet is beyondthe fence, in the midstof the darknessand the jackals.In Jerusalemheearnshis livelihood by writing"intricatearticlesfull of complicatedtables"for scientificmagazines.But his detailed drawings,with theirprecise calculations,sketch a chaotic world powered by desiresanddrives.Withthe polyphonicformationof his protagonist,Oz overcamethe two aforementioned imitationsof language:first, that languagerepresentsheprimevaloriginsof thesoulonlyina sketchy,general,andabstractmanner; econd,thatlanguageslices and scatters he fullnessofexistence,and thus contradicts he fundamental tructureof naturein90

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

14/20

which sin and holiness, sanity and madness struggle and reconcilesimultaneously.Oz turned hesplittingandslicingnatureof languagentoa sourceof strength:differentdescriptionsakenfromthe differentpartsof thestoryare unitedtogether n order o encirclesomethingwhichnonecould encompassalone. In order to give name and substance to theprecultural"things,"Oz wove the words together like thin fibersinterwoven o create a strongrope.155.2 The polyphonicstructure s not the only factorin the storywhichbindsthequarrellingides.Thetechniqueof forming"chords,"escribedpreviously, s anotherdevice whichshedslighton the close kinship hatexists between the antagonists.This technique appearsseveral timesthrough he courseof the story (pp. 61, 62, 64, 65, and more),reachinga climax in the last paragraphof the story as it reversesthe contrastbetween the melody of the bells and the wailing of the jackalsto ametaphoricaldentification.The finalparagraph pensby emphasizingthe "festiveness"of the monastery'sbells, which is answeredby the"savageand irreverent"wisted laughterof the jackals.Yet, the bells'festiveness ies themwiththe"festive"behaviorof thejackalsdescribedon the previouspage (p. 73). Furthermore, he jackalsare explicitlylikenedin thispictureto "priests," termtakendirectlyfromthe worldof churchesandmonasteries.

One of the interestingmethods of establishing he chords is atextual shift from one detail to another which is in no other wayconnected.In thiscase, the juxtaposition reatesan implicitconnectionbetween the otherwisedisconnecteddetails.A characteristicxampleofthis device is the transition rom, "In those days Dov was lord of theorchard" o "Theold fatherof Samsonthe bullruledthe barns n thosedays. Generations f jackalshave passedaway since then"(p. 64). Thevery catalogue-likenature of the descriptionhints to the connectionbetween its parts. This connectionis highlightedby the hierarchicalphrasing(Dov is the "lord of the orchard,"he bull "ruled he barns")and by the numerousparallels hattie Dov to the bull and the jackals.Similar hifts inkEhudto thejackals pp. 65,73).A furtherdevice whichblurs he divisionbetweentheantagonistsis the numerous anthropomorphismsncluded in the story. Theseanthropomorphisms,onstructedby the use of metaphorandsimile,arebutanotheraspectof akinshipwhichthestorycreatesbetweenman andthe animals.Indeed, from the comparisonof humanbeing to animalsthe opposite course is inducedas well, and Oz concretizesthishiddenimplicationagainand again.Already n the firstparagraphhe flies areportrayedas havinghumanqualities,and laterthe cries of the jackalsaredescribedascrying, aughter,andlamentation.Thewailingof a lonejackal s comparedto a violinisttuninghis chordand the chords of hisfriends(p. 65). In otherdescriptions he jackalsaredescribedas drivenby malice,evil,hate,and even grief (p.68).Thejackalsapproachinghebody of Ehudarelike"festivepriests n ceremonyof mourning" p. 73).Onthesurface hestorysetsupa bitterstrugglebetweenmanandjackal:the kibbutzfence is like a "fortress"p. 73) protectedfrom its enemy.

91

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

15/20

And yet, a ramifiedmetaphoricalnet portraysman as jackaland thejackalsas humanbeings, blurringcompletelythe border between thewarringcamps.5.3 This complex situation n which the conflict existingbetween theantagonistss accompaniedby a rich arrayof devices that point to aproximityand the possibilityof a reciprocalbond between the rivalpartiescharacterizes ll of Oz'sworks.'6From t a two-faceteddialecticalsituation s implied. First,in the conflict between darknessand light,between the primevalwaters and the land,the sides are not composedof merelyone element.The waterscontainnot only destructive orces,but a fertilizingpower as well. In the world of darkness, he world ofthe jackals, hereis malice and wildnessbut holinessas well.17Second,the world of darkdepthsis not justthe swornenemyof the illuminatedworld, for it is also the sourceof thatworld,nourishingt as the rootsof the tree nourish ts highestbranch(thissimileappearslaterin Oz'sworks,see "StrangeFire,"1965,andmore).The total defeat which fallsupon the representatives f culture n "BeforeHis Time" derivesfromtheir denialof this situation, rom theirperceptionof the relationshipbetweenmanandjackalas a solely antagonistic ne. According o theiroutlook,a linearevolutionexists nnature,whosepinnacle s man-culture-consciousness.On man falls the taskof fightingwith all his strengthsoas to safeguard he attainmentof this evolution and consolidate t. Onhumanbeingsfallsthe taskof protecting hemselves rom thedark orcesburrowingunderneathhem andattempting o eradicate hemfrom theuniverse.And thus, the kibbutz fences itself in from the jackalsanddarkness;Dov battlesagainst hejackalsand Ehudagainst heArabs.Thiswar is doomed to failurefrom its inception,for they strugglewith aprimeval foe, firm and unvanquishable.Furthermore, he dualisticcharacterof the battlingsides revealsthat their war is a war againstthemselves.Evenif itwereintheirpowerto win, indoingso theywouldcut themselvesoff from sourcesof theirvitalityandcreativityandbringupontheirown annihilation.n hislaterworksOz emphasizesover andover thefollyof attemptingouproot heprimeval orcesfromtheworld,thenecessityof people to exposethemselves o them andto be nurturedfrom the power and sagacitystoredwithin them. In otherwords, theconception of evolutionas a pyramid in which man-cultureare thepinnacleis an oversimplifiedand misleadingconception.The upwardprogressiono the summit mpliesa distancing rom the base, from theorigins, n which manis one with natureandwith the abundanceof lifewithinhim.Disregardinghiscondition,wishingto "setright" he worldthrough deologicalor religiousmovements,bringsaboutthe downfallof therepresentatives f culture(thekibbutzmembers,the monks).6. ConclusionAs mentioned,not incidentallywas "BeforeHis Time" the firstof the storieswhichOzlater ncluded nWhere heJackalsHowl.Severalof the componentsof thisstorybecome foundationstonesin Oz's laterworks.Amongtheseit is worthwhile o note the following:92

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

16/20

1. The basic foundationsof the soul, the mannerin which they areexposedand the possibleconnectionsamongthem,standin the centerof Oz'sworks. The vigorouseffortto uncoverthese foundations reatesa dual structure n Oz's stories.First,an inclination owards stories ofcreation, towards myth. Second, finding a modem reality that willconcretize heseessential oundations.Themodem worldset forth nOz'sworks,ononehand,obscuresprimevalprocesses,yet, ontheotherhand,resurrectshemthrougha richarrayof symbols.The bull and the flies,the bear, the jackaland the owl, the water,the gold and the silver,thelead and the copper, recall the stories of Mardukand Tiamat,Osiris,Jesus,Lilith, he alchemists earch orgold,and more. Thisphenomenonreappearsagainandagain n Oz'slaterworks.Thus,for example,NogaBerger, heprotagonistof Elsewhere,Perhaps 1966) ollowsthefiguresof Aphrodite-Venus (hernameis the Hebrew nameof the starVenus,p. 344) and The VirginMary (by means of herpet name Stella-Marris,the pomegranate he singsabout,and more).Rimona,one of the maincharacters f APerfectPeace(1982) sportrayedasPersephone"Rimon"is Hebrewforpomegranate,he mostprominant ymbolof Persephone;she has contactswith the spiritsof the dead, and more)and Mary(thecyclamen and the almond, which are connected to her figure, arecommon symbols of Mary). The significancewhich the alchemistsattached to mercury indicates that YonatanLifshitz, who sees themoonlightas mercuryduringhis frighteningnight journeyto Petra,reachesin this journeythe primevalsubstanceof his soul (A PerfectPeace).l8Oz conceives of the primevalforceswithinthe soul as concreteentities, orces which have existedin the world sinceitsverybeginning.These forces inhabithisworldas archetypesor Platonic orms. He doesnot alwaystakepainsto recreate hem. Often he is contentwithmerelypointingthese forces out, assumingthat they are as meaningful n thereader'sworld as theyarein hisown.2. The extentto which the primalforcesareconcretizedvaries.In thecase of minorcharactersOz makesdue withcreatinga parallelbetweenhis character and some mythical figure, using one or two symbolscharacteristicf thismythical igure o establish he connection.Thecoreof the storyrevolvesaroundthe concretizationof the forces withintheprotagonists.This concretization s achieved, as seen previously, bymeans of a dualstructure f conflict andconciliation.Thisstructureets,as itsbasis,a sharpconflictbetweendiametrically pposedforces,whosenature s realizedthroughdifferent detailsfrom the characters'world.The conflict containsthree main facets which are interrelated.First,in the course of the work it becomes apparentthat each of thebattling forces is not homogenous. And thus, if on the surface anunrelentingwar isbeing wagedbetween thesetwo enemies, hen mplicitin the story is their possible resemblance and mutualattraction.Forexample,in the novel Elsewhere,Perhapsa persistentstruggleis heldbetween Israeland herArabneighbors.The narratorwhoadopts,amongotherthings,the stand of thekibbutzmembers,portrays hisstruggleas

93

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

17/20

a conflict between light-culture-man and darkness-nature-woman.However, a careful reading of the novel reveals that within each of theantagonists are contained elements of its enemy, and implicitly they aredescribed as a man and a woman ready to make love.From these two aspects is derived a complete blurring of anydichotomous notion: heaven and earth, culture and nature, male andfemale, etc. These three trends create a world in which, on the one hand,an element is its own contradiction, and on the other hand, an elementis transformed into the element which is in opposition to it.19This worldis one in which suffering is pleasure and pleasure is suffering, a worldin which an attraction to life is an attraction to death, and yearning fordeath is a strong yearning for life. The Arab in Oz's works is the enemyand the fertilizing phallus (Elsewhere, Perhaps, A Perfect Peace, and

more), and redemption in this world is achieved only through a descentto the underworld (A Perfect Peace). This is a fluid world, whoseelements reject any fixed labels. This world repels any value-orienteddivision between "good" and "evil," "righteousness"and "corruption."Oz, as stated, does not seek to "capture the flow of things with words."His main interest lies in the permanent foundations of the soul and ofthe world. This experiential world is characterized by opposites andcontradictions and by a reciprocating exchange between its parts. Thetextual structure,in which a dual structure of opposition and conciliationthat defies any possibility of bestowing a fixed label to its parts isestablished, parallels in its character the world reflected through it-aworld in which all elements are mobile, flowing and changing.University of Florida

NOTES1. The storiesof Wherethe JackalsHowl were rewrittenby the author(AmOved edition,1976).The presentdiscussiondeals with the firstversionof"BeforeHis Time"(1965).The new versionis mentionedin severalcasesin order to illuminatesome of the arguments.The quotationsfrom thisversion are in accord with the English edition of the book (1981).Referencesto the Englishedition are markedEE.2. Thistopicisdealt withindetail nthechapter"AmosOz-An Introductoryessay" n Balaban'sBetween God and Beast,An Examinationof the Proseof Amos Oz (1986).3. These unknown storiesby Oz are contained in the appendixto BetweenGod andBeast.A detailedexaminationof themis includedin chaptertwoof the book.4. This topic is elaborated n the chapter"Waterand Sky" n Between Godand Beast.The ocean is one of the mainsymbolsdealt withby Jung.Oz'sdebt to Jungis amplydiscussed n the above research.5. Oz is quite familiarwith Egyptianmyth. In a letter dated June 12, 1984,he wrote to me about his trip to Egypt, where he "finally becameacquaintedfrom up close with some of the protagonistsof the stories ofmy youth (the cows-goddess Hathor,the gods Isis and Osiris,and Seth,

94

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

18/20

the murdererof hisbrother,and Horus-the avengerof hisfather,andthejackalgod Anubis,who is in chargeof mummification)."6. Theadjectives"green"-"greenish"ies thesespheres.Justas the flies exacta "green" evenge, so does the jackalthatresideswithinthe dog send outfromhis depths "volleysof greenish aughter" p. 73).7. On the four stages of this myth and their interrelation ee Frye (1971,p.192).8. On thistopic see, amongothers,the thoughtsof Saussurebroughtout laterinthe chapter.The connectionbetween culture, houghtandlanguagehasbeen amply discussed. Descartesarguedthat animalsdo not think,sincethey do not speak (1970, 245). For a detailed discussion of Descartes'sattitude see Malcolm, 1977. Frege, whose theory has established theframework or the modernexaminations f thereciprocalaffinitybetweenlanguage, meaningand thought,accepted Descartes'sassumptionson thispoint (1980).DavidsonrejectsDescartes's dea concerning he connectionbetween languageand thought,but he shareshis opinionthatanimalsdonot think(1984).Oz touched upon the above connection more than once in hisarticles:"Ihope thatthe writtenliterature an slowly by slowly enrichthespoken language. In the final analysisthe borders of language are theborders of your world and that which you cannotexpressin words youcannotgraspwell in thoughteither.The chance to expresscomplexityandsubtlety is the chance to enrich life and live it by a subtle and complexrhythm.The restrictionof speech is one of the primaryfoundations ofrudenessand generalunbotheringblaze'ness" 1979,p. 28). This is typicalWittgensteinphrasing (compare:"The limits of my languagemean thelimitsof my world,"1922,p. 149).But thisis a similarityof phrasingonly.Accordingto Wittgensteinanguagecannot be enriched.9. In many of his books Jung expresses the idea that this world of theunconscious, which language has no way of describing, can only beexpressed by means of symbols (see 1959,p. 6; 1966,p. 70, andmore).10. Indeed, in the second version of the storythe word "thing"was replacedby the word "force" p. 83, EE p. 89).11. The idea that consciousness s a dividing and splittingelement has beenaccepted in Westernphilosophysince Kant.Levi-Strauss nd his disciplesadded to thisnotionthe assertion hatconsciousnessnotonly separatesandsplits up its objects, but also receives them, according to its nature,inoppositions.Oz touches on this issue in his Touch the Water,Touchthe Wind,in the writingsof the dying, hallucinatingErnstCohen:"Music, herefore,is melodic mathematics,and whoeverhas the key is able (in principle)totransformmatter into energy, energy into suffering,sufferinginto time,time intowill, will intospace, everything ntoeverythingelse in anyorderwhatever, as everything truly is before the mind breaks it down intodifferent elements, some of which are completely distinct from others"(1973,p. 169,EE 1973,p. 160).12. NuritGertzstresses the structureof opposites which typifies Oz's works(1980,p.55)."Thestructure f oppositions"sutilizedbyher fordescriptionand interpretationof all Oz's works (see Chapter3 of her book). Thepossible synthesisbetween the antagonists s not discussedby her at all.13. The verb "cast"whichdescribesthetunehere,reappears aterin thestory:"Aneternalcurse is cast between house dwellers and those who live inmountainsandravines" p.73).Thisrecurrence trengthenshetie betweenthe sounds of the radioand the bells and the central conflict of the story.

95

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

19/20

14. The leg is a common phallic symbol. See de Vries, 1981, p. 294, and Cooper,1984, p. 96.15. The polyphonic technique as a typifying feature of Dostoevsky's work wasamply dealt with by Backtin (1984). Oz made highly complicated use ofthis technique in the novel A Perfect Peace. An intricate net of analogiesconnects all the main characters in this novel, alluding to the "perfect peace"they all reach in the final chapters. (See Between God and Beast.)16. This topic is elaborated in the chapter "Warand Peace" in Between Godand Beast.17. As noted, the jackals in the story are compared to priests and to monks.One may add that Anubis, the jackal god, helped Isis to gather the piecesof Osiris' flesh, and traditionally he plays the role of Jesus, that of thepsycopomp (de Vries, p. 275).18. This symbolism is dealt with in detail in Between God and Beast.19. Compare this description to the manner in which Barbara Johnsoncharacterizes the analyses of the works brought out in her book: "Reading,here, proceeds by identifying and dismanteling differences by means ofother differences that cannot be fully identified or dismantled. The startingpoint is often a binary difference that is subsequently shown to be anallusion created by the workings of differences much harder to pin down.The differences between entities (prose and poetry, man and woman,literature and theory, guilt and innocence) are shown to be based on arepression of differences within entities, ways in which an entity differsfrom itself. The 'deconstruction' of a binary opposition is thus not anannihilation of all values or differences; it is an attempt to follow the subtle,powerful effects of differences already at work within the illusion of abinary opposition" (1985, pp. x-xi).There is an interesting similarity between Oz's concepts of languageand the theory of Derrida (the 'erasure,' the rejection of hierarchicaloppositions, and more), despite their diametrically opposed points ofdeparture. A cornerstone of Derrieda's thought is the complete rejectionof the possible existence of an origin. This rejection leads to his conceptionof "writing," of "differance," etc. (See, for example, Of Grammatology,1980.) In contrast, in Oz's work, based on Jungian concepts, the origin isconceived as a concrete and valid entity. Language "erases" itself in Oz'swork due to the contradiction between its character and the nature of thisorigin, its complexity and the inner flow which characterizes it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY*Balaban,Avraham.Between God and Beast-An Examinationof the ProseofAmos Oz. Am Oved: Tel Aviv, 1986.Bakhtin, Mikhail. Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Trans. Caryl Emerson.

University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1984.Cooper,J.C. AnIllustratedEncyclopediaof Traditional ymbols.ThamesandHudson: New York, 1984.Davidson, Donald. "Rational Animals," in Dialectics, 4 (1982).. "Thought and Talk." In his Inquiries Into Truth and Interpretation.Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1984.Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Trans. Gayatri C. Spivak. The JohnsHopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1980.Descartes, Rene. Philosophical Letters. Clarendon: Oxford, 1970.

96

-

7/29/2019 Amos Oz Style

20/20

Ferguson,George. SignsandSymbols nChristianArt.OxfordUniversityPress:Oxford,1961.Frege,Gottlob.PhilosophicalandMathematicalCorrespondence.Trans.HansKaal.Universityof ChicagoPress:Chicago,1980.Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism:Four Essays. Princeton: PrincetonUniversityPress,1971.Gertt,Nurith.Amos Oz-Monograph. SifriatPoulirn:Tel Aviv, 1980.Johnson,Barbara,1980. The CriticalDifference. Johns Hopkins UniversityPress,Baltimore.Jung,C. G., TheArchetypesand the Collective Unconscious.Trans.R. F. C.Hull.PantheonBooks: New York,1959.. The Spirit n Man,Art and Literature.Trans.R. F. C. Hull.PantheonBooks:New York,1966.Malcolm,Norman.ThoughtandKnowledge.CornellUniversityPress:Cornell,1977.Oz, Amos."PurpleCoast."*Davar,18may, 1962,p. 22.. "BeforeHis Time."Keshet,no. 15 (1962),pp. 6-18.. Where theJackalsHowl. Masada:Tel Aviv, 1965.. Elsewhere,Perhaps.SifriatPoalim:Tel Aviv, 1966.[English:HarcourtBraceJovanovich:New York,1973]. Touch theWater,TouchtheWind.AmOved:TelAviv,1971.[English:HarcourtBraceJovanovich:New Yorkand London,1974]. Where heJackalsHowl. AmOved:Tel Aviv,1976.[English:HarcourtBraceJovanovich:New Yorkand London,1981]. "AnInterview with AmosOz,"IDF Radio,Tel aviv, 14-24February,1978.. UnderThisBlazingLight. SifrialPoalim:Tel Aviv, 1979.. A PerfectPeace. Am Oved: Tel Aviv, 1982.[English:HarcourtBraceJovanovich:New Yorkand London,1985]Saussure,Ferdinandde, 1974.Course n GeneralLinguistics.Fontana,London.Vries, A. de, 1981. Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. North-Holland,Amsterdamand London.Wittgenstein,Ludvig, 1922.TractatusLogico-Philosophicus.Harcourt,Braceand Co., New York.'Amos Oz's works that are markedwith an asteriskexist in Hebrew only.Translations f the quotations rom theseworkshave been done by me, A. B.

CALL FOR PANELISTSStuart Peterfreund, Chair-Designate of the CELJ session at the

1991 NEMLA meeting, is seeking panelists for that session, to be devotedto the question "What Makes a Journal (or Editor) an Award-Winner?"Peterfreund is particularly interested to include on the panel editors ofjournals that have won CELJ awards during the past several years and/or those who served on the panels that judged for and conferred thoseawards. Anyone interested in serving on the panel should contact Peter-freund at the following address: Department of English, NortheasternUniversity, 360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115.

97