Amazon Town: A Study of Man in the Tropics. Charles Wagley

-

Upload

clifford-evans -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Amazon Town: A Study of Man in the Tropics. Charles Wagley

-

508 A merican Anthropologist [56, 19541 Family Life; 111, Government; IV, Fiestas; V, Mans Fate; and VI, Rituals in Text Translation. There is also a lengthy foreword in which Bunzel discusses anthropo- logical field methods and her experiences among the Zuni; a series of appendices with valuable material on markets and prices, among other things; a glossary; and a selected bibliography. Regrettably, there is no index. It is especially to be regretted in an anthropological monograph, among whose principal general values is the offering of comparative materials against which to test species-wide generalizations, or out of which to develop documentation for the existence of cultural complexes.

Because comparative studies often rely upon only the broadest generalizations found in individual monographs, I feel it important to raise some questions regarding the sweep and intensity of some of Bunzels generalizations. Many of them are stated in all or none terms, or always or never terms, and the technique of field study which uses a seIected number of somewhat deviant informants does not seem to lend itself well to the verification of such all or none propositions.

Still another form of proposition which we find scattered throughout the volume, and about which doubt must be expressed, is illustrated by the following: In spite of the fact that therejs great fear of malice and sorcery, this is never associated with food. There are no accusations of poisoning or working evil magic with food. All of these facts indicate that the QuichJs feel relatively secure in regard to subsistence (my emphasis, MT). What we have here is a high-level generalization regarding psycho- logical security patterns, derived from a limited number of observations regarding how people behave when food is involved in their social relations. The generalization may in fact be true, but it should be pointed out that exactly the opposite generalization is equally derivable from the same evidence, if one employs a contrary, but equally sensible hypothesis. That is, people may give generously to each other either to cover up deep anxieties or because they have no anxieties. In the Chichicastenango case, the deeply felt anxieties about land tenure would seem to throw some doubt upon the contention that there is relative security regarding subsistence. In Eastern Guatemala, for instance, anxiety about land tenure and about subsistence are closely intercon- nected.

I t should immediately be added, by way of commendation, that Bunzel is ob- viously a sensitive observer, able to establish rapport with informants so as to secure materials about certain ordinarily secret features of the lives of the people, and clearly has a good ear for more delicate nuances of interpersonal behavior. Moreover, the de- scription of the general round of life, if taken somewhat more moderately than as presented by Bunzel, tallies sufficiently well with independently gathered evidence regarding the cultural complex of the area, so that we must be indeed grateful to her for offering us this body of comparative material, even a t such a delayed date. Students interested in a comparative analysis of the differential functions of ritual and religion have here much rich material on which to draw.

MELVIN TUMIN, Princeton University

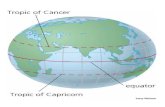

Amazon Tows: A Study of Man i n the Tropics. CHARLES WAGLEY. New York: The Mac- millan Company, 1953. xi, 305 pp., illus. $5.00. This volume of community studies, presented in a readable prose, wrapped in a

colorful jacket, illustrated with charming line drawings (by the Brazilian Jog0 Josh Rasdla) and a clear map, bound in a hard cover, and published by one of the large commercial houses, is indeed a step forward in anthropological writing. The book, in

-

Book Reviews 509

this format, should not only be most useful in undergraduate courses in both sociology and anthropology, but shouId also reach a fair number of the reading public. Unfor- tunately, the publisher has burdened the book with a price which seems higher than necessary, and a t times one wonders if Macmillan Company might not have been in- fluenced by the text itself, with its references to high prices charged by the commer- cia& in Brazil.

Amazon Town is the result of Wagleys familiarity with the town of ItL (an assumed name of a small community in the Lower Amazon drainage) off and on from 1942 until 1948 when he, his wife, and Mr. and Mrs. Eduardo Galvgo spent 4 months in the com- munity for the UNESCO Amazon survey of the International Hylean Amazon Insti- tute. As a result of this groups cooperative activity and the complete absence of lin- guistic problems, the field work was as thorough as if twice this amount of time had been spent in the area.

With the exception of Chapters I and VIII (to be discussed later), the text is ar- ranged so that all the aspects of a monographic community study are presented, but are made more readable by grouping the various facets of life into broad topical chap- ters. This arrangement gives the reader the feeling of the actual existence of people living in a typical Amazon community, rather than providing only isolated topics ex- tracted from the whole. Such chapters include An Amazon Community describing the physical layout and historical perspective, Making a Living in the Tropics, Social Relations in an Amazon Community, Family Affairs in an Amazon Com- munity, People Also Play which covers celebrations, religious activities, social events, dances, etc. and From Magic to Science describing the superstitions, magic and folklore intermixed with the contact with modern medicine, sanitation and hygiene.

To the reviewer, familiar with the communities of the Amazon, both larger and smaller than It&, other Amazonian county seats similar to It&, and with the life of the rubber cutter, the caboclo, the hunter, the trader, and people of higher status during the year 1948-49, the descriptions of It& sound as if they could apply equally well to practically any part of the Amazon with only some minor local variations, in spite of Wagleys insistence that I t& is not a typical community. The authors excellent, vivid descriptions of the houses, stores, the community life, the traders relationships to the people, the details of slash and burn agriculture, the preparation of the basic food sup- ply (manioc), superstitions, education-or more realistically the lack of educational fa- cilities-transportation, religion, social events and jestas, etc., are definitely typical of life in the Lower Amazon a t least. Granted, there might be special situations in It& which have caused greater impact of the larger society on this community than on some of the more isolated places in northern Brazil, but Wagley should not underestimate It6 as quite representative of the Amazonian culture pattern-the end result of the interplay of Europeans, Negroes and Indians in a series of historical events beginning with the European contact in A.D. 1500, the intense colonization by the Portuguese after A.D. 1600, the rubber booms and collapses of 1900-1912 and 1942-1946, and many other minor economic situations. The authors constant efforts to put this community into the framework of Brazil as a whole not only gives the reader a better understanding of community life in It& but also an insight into the totality of Brazilian culture.

There is important information in this book for the planners of Technical Assist- ance programs or Point Four throughout the world. Wagley clearly demonstrates the tremendous difficulties and complications which arise from health, sanitation and agricultural programs which fail to consider the reaction such a single community, as part of a larger culture, will have to these innovations in the context of their own cus-

-

510 Americalz Arzthropologist 156, 19541 toms, beliefs, and pattern of life. For all persons working in this type of World Aid, the book should be required reading.

The professional anthropologist may react less favorably to Wagleys first and last chapters than to the remainder of the book. The reviewer did not find the comparison in Chapter VII, between It& and Plainville, U. S. A., particularly helpful. Perhaps for the general reader, however, the role of It& in Brazilian society is better understood by comparing it with an American community in the context of American society.

After this comparison, Wagley ends his book with the theme that if a technology adapted to the tropics is devised, then the Amazon can become a better-developed agri- cultural area in the future. He states that in so doing, there must be a concomitant modification of the Iocal society and of the traditional culture, and that regardless of what happens, if a technical assistance program is to have any value to the people of underdeveloped areas, care must be taken not to reinforce the existing social and eco- nomic status quo of the region.

Chapter I-The Problem of Man in the Tropics will cause the most controversy. Wagley takes a position between the violent pessimists who view the Amazon as green hell and those extreme optimists who see the Amazon as the future bread basket of South America in stating that the Amazon has much more potential from an agri- cultural standpoint than many people believe, provided there is a change from pred- atory agriculture of infertile, lateritic, upland soils to lowland crops in the areas sub- ject to flooding. In setting the background for the theme of the book, . . . the study of a culture, of the way of life which has been created by man in the Amazon Valley of Brazil (p. 17), Wagley undertakes a superficial discussion of vital statistics, diet, mineral and vitamin deficiencies, absence of roads and electric light plants and other modern conveniences, the gathering economy, slash and burn agriculture, living condi- tions in a tropical climate, a comparison of growth between Panamanians (as repre- sentative of a tropical situation) and Europeans, meteorological data, diseases, and soil composition. Here, too frequently, Wagley has become the victim of generalization and has failed to check the more recent physical anthropological, medical and nutri- tional literature on diet, difference on body build and stature with reference to environ- ment, differences in body requirements and the calorie intake when compared to body size rather than when compared to a set of ideal statistics published by NRC or similar agencies. His comparison of the Panamanian, as a typical representative of the Ameri- can tropics, with Europeans is not accurately stated, according to a physical anthro- pologist whom the reviewer consulted. It is too bad that Wagley marred an otherwise excellent book with this effort to generalize on topics which are actually beyond the scope of the problem and which should be discussed at greater length than he appar- ently desired or was allowed.

CLIFFORD EVANS, U . S. National Museum

Survey of African Harriage and Family Life. Edited by ARTIIUR PHILLIPS. New York: Oxford University Press, 1953. xli, 462 pp., map. $9.00.

This volume, the outcome of a proposal submitted to the World Conference of the International Missionary Council in 1938, deals with the effects of Western civilization upon marriage and the family in Africa south of the Sahara. It was originally visualized as a fact-finding appraisal of the present situation, which would help to resolve the confusion created by the frequently conacting requirements of Government statutory law, Church law, and Native customary law, guide Governments and Churches to a