Age and Gender Differences Associated with Family … · 2015-06-13 · Age and Gender Differences...

Transcript of Age and Gender Differences Associated with Family … · 2015-06-13 · Age and Gender Differences...

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

228 www.hrmars.com/journals

Age and Gender Differences Associated with Family Communication and Materialism among Young Urban Adult Consumers in Malaysia: A One-Way Analysis of

Variance (ANOVA)

Eric V. Bindah PhD Scholar, University of Malaya, Department of Marketing, Faculty of Business &

Accountancy Building, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Email: [email protected]

Prof. Dr. Md Nor Othman Head of Marketing Department, University of Malaya, Faculty of Business & Accountancy

Building, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Abstract The main purpose of this study is to examine the differences in age and gender among the various types of family communication patterns that takes place at home among young adult consumers. It is also an attempt to examine if there are differences in age and gender on the development of materialistic values in Malaysia. This paper briefly conceptualizes the family communication processes based on existing literature to illustrate the association between family communication patterns and materialism. This study takes place in Malaysia, a country in the Southeast Asia embracing a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society. Preliminary statistical procedures were employed to examine possible significant group differences in family communication and materialism based on various age group and gender among Malaysian consumers. A one-way analysis of variance was utilised to determine the significant differences in terms of age and gender with respect to their responses on the various measures. When there were significant differences, Post Hoc Tests (Scheffe) were used to determine the particular groups which differed significantly within a significant overall one-way analysis of variance. The implications, significance and limitations of the study are discussed as a concluding remark. Keywords: Age Group, Gender, Family Communication, Materialism Introduction As reported by several studies on consumer socialization by Bindah and Othman (2012, 2011), most modern societies deals with at least eight major socialization agents (Reimer and Rosengren, 1990). Some examples are family, peer group, work group, places of worship, schools and others. Studies have found that people often interact with socialization agents and

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

229 www.hrmars.com/journals

then take in consciously and unconsciously social norms, values, beliefs, attitudes, consumer skills (e.g, Kasser, 2002; Korten, 1999). Ultimately, their purchasing decisions and consumption patterns are influenced by these agents. Ward (1974) offered a classical definition of consumer socialization: “the processes by which young people acquire, skills, knowledge and attitudes relevant to their functioning as consumers in the marketplace” (Ward, 1974, p.2). Family influences on consumer socialization seem to proceed more through social interaction than purposive educational efforts by parents (Ward, 1974a). Given the more subtle nature of family influences, researchers have turned their attention to general patterns of family communication as a way to understand how the family influences the development of consumer skills, values (including materialism) and their purchasing decisions. On the other hand, materialism among today’s youth has received strong interest among educators, parents, consumer activists and government regulators. However, the majority of researches on materialism were conducted mostly in the Western cultures, leaving room for speculations on the development of materialistic tendencies and inclination among young adult consumers in Eastern cultures, particularly in countries such as Malaysia. On these bases, this study attempts to investigate if there are differences in age and gender in terms of the development of materialistic inclination among Malaysian consumers and the type of communication patterns that takes place at home, which ultimately reflects on how consumers consume products and services in the market place. This leads us to the specific objectives for this study.

Objectives of the Study The objectives of this study are as follows:

a. To examine age differences in the various type of family communication patterns at home among young adult consumers in Malaysia.

b. To examine gender differences in the various type of family communication patterns that takes place at home among young adult consumers in Malaysia.

c. To examine age differences on the development of materialistic values in Malaysia. d. To examine gender differences on the development of materialistic values in Malaysia.

Literature Review Materialism This paper adapts the view of materialism as a value orientation, which is centred on three main components: acquisition centrality, acquisition as the pursuit of happiness, and possession-defined success (Richins and Dawson, 1990). According to Richins and Dawson (1990), materialism viewed as a value, is described as an organizing central value that guides people’s choices and behaviour in everyday life. It is an enduring belief that acquisition and possessions are essential to happiness and success in one’s life. Broadly defined, materialism is

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

230 www.hrmars.com/journals

any excessive reliance on consumer goods to achieve the end states of pleasure, self-esteem, good interpersonal relationship or high social status, any consumption-based orientation to happiness-seeking and a high importance of material issues in life (Ger and Belk, 1999).

Family Communication and Materialism The degree of influence that a child has in purchasing is directly related to patterns of interaction and communication within the family (Carlson and Grossbart, 1988; Carlson, et al., 1992; Rose, 1999). Research on family communication has linked the type or quality of communication to a variety of parental practices and consumer competencies in children. Family communication provides a foundation for children’s approach to interact with the marketplace, and is inextricably linked to parental approaches to child-rearing (Carlson and Grossbart, 1988; Rose, 1999), and influences the development of children’s consumer skills, knowledge, and attitudes (Moschis, 1985). The domain of family communication includes the content, the frequency, and the nature of family member interactions (Palan and Wilkes, 1997). The origins of family communication research in marketing can be traced to a study conducted in political socialization which utilized two dimensions from Newcomb’s (1953) general model of affective communication (McLeod and Chaffee, 1972). The first dimension, socio-orientation, captures vertical communication, which is indicative of hierarchical patterns of interaction and establishes deference among family members (McLeod and Chaffee, 1972). This type of interaction has also resulted in controlling and monitoring children’s consumption related activities (Moschis, 1985). The second dimension, concept-orientation, actively solicits the child’s input in discussions, evaluates issues from different perspectives, and focuses on providing an environment that stimulates the child to develop his/her own views (McLeod and Chaffee, 1972). This type of communication results in earlier and increased experience and learning of different consumer skills and orientations among children (Moschis, 1985). Bindah and Othman (2012) identified a third dimension associated with family communication pattern at home. Religiously-oriented family communication was found to have a significant association with the development of materialism. A recent study by Bindah and Othman (2012) in Malaysia hypothesized a significant relationship between young adult consumers and materialism and their results were significant. In summary, studies have shown that the family communication environment affects the endorsement of materialistic values (e.g., Bindah and Othman, 2012, 2011; Moschis and Moore, 1979b; Moore and Moschis, 1981; Flouri, 2000).

Demographic Variables Associated with Materialism In terms of demographic factors, research has also been conducted to correlate certain demographic variables such as age and gender with materialism. The following is a review of literature.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

231 www.hrmars.com/journals

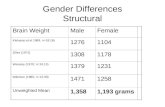

Age and Materialism Studies have associated age variable with materialism. Table 1.1 provides a summary of major research findings of age variable and its association with materialism. Refering to Table 1.1, Moore and Moschis (1981) surveyed 784 respondents from sixth through twelve grade students, using six items measuring materialistic attitudes. Their findings indicated that age was a strong predictor of materialistic value. Moore and Moschis (1981) have also surveyed 601 adolescents from middle and senior high school, with younger adolescents (below age 15), and older adolescents (Above age 15). Younger adolescents tended to be more materialistic than their older counterpart. A study by Belk (1984) has proposed and tested three measures of materialistic traits: possessiveness, non-generosity, and envy. In this study exploratory data relating these traits to age were examined. The results indicated that two of the three materialism measures were found to be significantly related to the age of the subjects. Envy showed a slight negative correlation with age (r=-.19, p< .0001) while non-generosity showed a slight positive correlation with age (r=.12, p< .02). The apparent decline in envy with age might be due to having achieved a greater proportion of one's material goals, having adjusted material goals to financial means, or having come to place less social importance on material goods. Achenreiner (1997) surveyed 300 children from the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, 7th, 10th grades aged 8, 12 and 16 respectively. The findings indicated the materialistic attitudes of one age group were not significantly different, from those of other age groups. Materialism did not vary dramatically as a function of age for children between the ages of 8 and 16. The findings indicated that materialism varied only marginally with age. Middle-aged people (40-50 years of age) were more likely to cite power and status as the reasons why people own things than are those in other age groups. Old people treasure their past experiences and value keepsakes and mementos, both in the form of possessions and special places. Past studies suggested that egoistic materialism declines as age increases. Generally speaking, older people care less about material possessions and feel happier than younger people (Sheldon and Kasser, 2001). More recently Chaplin and John (2007) conducted a study with children and adolescents in the age group of 8 to 18 years old to find an explanation for age differences and its effect on materialism. The study was based on a conceptual model similar to the one proposed by Kasser et al. (2004) which specified that materialism is developed through two

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

232 www.hrmars.com/journals

Table 1.1: Summary of Major Findings Between Age and Materialism

Author

Sample

Materialism Measure

Key Findings

Moore and Moschis (1981).

784 respondents from 6th through 12th grade students.

6 -items measuring materialistic attitudes.

Age was a strong predictor of materialistic values.

Moschis (1981).

601 adolescents from middle and senior high school.

6- items measuring materialistic attitudes.

Younger adolescents tended to be more materialistic than their older counterpart.

Belk (1984).

338 subjects across a variety of occupations.

3-items measure of Materialism; 9 items measuring possessiveness, 8 items measuring envy, 7 items measuring non generosity.

The results indicated that two of the three materialism measures were found to be significantly related to age. Envy showed a slight negative correlation with age, while non-generosity showed a slight positive correlation with age.

Achenreiner (1997).

300 children from the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, 7th, 10th grades Specific ages targeted (8,12 and 16).

5- items measuring materialism adapted from Richins (1987).

The materialistic attitudes of one age group were not significantly different, from those of other age groups. Materialism did not vary dramatically as a function of age for children between the ages of 8 and 16. The findings indicated that materialism varied only marginally with age.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

233 www.hrmars.com/journals

Kau et al. (2000).

1534 Singaporeans in the age group of 15 to 54 years old.

7- items measure of materialistic inclinations from Richins and Dawson (1992)

People in different age group were observed to differ in their degree of materialistic inclination. Teenagers in the age group of between 15 to 19 years old were less materialistic; their older counterparts in the age group of 20 to 29 years old were more materialistic.

Flouri (2001).

124 adolescents boys aged 13-19 in the U.K.

Single item measuring materialism.

Materialism was inversely related to age. The effects were significant.

Chaplin and John (2007).

Children and adolescents in the age group of 8 to 18 years old.

10- items measuring Youth Materialism scale, using collage.

Age differences in materialism exist among children and adolescents. Early adolescents (ages 12–13) tended to be more materialistic than younger children (ages 8–9). Late adolescents (aged 16–18) were found to be less materialistic than early adolescents (aged 12–13).

Chan and Prendergast (2007).

281 adolescents aged 11 to 20 in Hong Kong.

A shortened 6- items version of Richins (2004) material value scales.

Age was not a significant predictor of materialism.

Paths: (1) from experiences that induce feelings of insecurity and (2) from exposure to social models that encourage materialistic values (Kasser et al. 2004). The results of their study revealed that age differences in materialism existed among children and adolescents. More specifically, early adolescents (ages 12–13) tended to be more materialistic than younger children (ages 8–9). And late adolescents (ages 16–18) were found to be less materialistic than early adolescents (ages 12–13) (Chaplin and John, 2007). The differences in the level of materialism among children and adolescents were attributed to the level of self-esteem among children and adolescents. Kau et al. (2000) have examined if the level of materialistic inclination differed among respondents with different demographic characteristics. Using a sample of undergraduate students in the age group of 15 to 54 years old, the findings revealed that people in different age group were observed to differ in their degree of materialistic inclination. In their study, teenagers in the age group of 15 to 19 years old were less materialistic; their older counterparts in the age group of 20 to 29 years old were more materialistic. Flouri (2001) surveyed 124

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

234 www.hrmars.com/journals

adolescents boys aged 13-19 in the U.K., and found that materialism was inversely related to age. The effects were significant (p= <.001). Chan and Prendergast (2007) surveyed 281 adolescents aged 11 to 20 to ascertain whether adolescents in Hong Kong endorsed materialistic values, and whether materialism changed with age during adolescence. Their results revealed that age was not a significant predictor of materialism. Gender and Materialism Studies have associated gender variable with materialism. Table 1.2 provides a summary of major research findings of gender variables and its association with materialism. Referring to Table 1.2, Moschis and Churchill (1978) conducted a study among adolescents age between 12 to 18 years old, to examine the relationship between male and female and whether they differed in their materialistic values. The result revealed that male adolescents hold stronger materialistic attitudes. The findings suggested that sex may affect the acquisition of certain consumer skills. Specifically, male adolescents appeared to know more about consumer matters (b = -.09, p < .008) and hold stronger materialistic attitudes (b = -.20, p < .001) and social motivations for consumption (b = -.13, p < .001) than their female counterparts. Churchill and Moschis (1979) conducted a study among adolescents to examine the relationship between male and female and whether they differed in their materialistic value. The result revealed that male exhibited stronger expressive orientation towards consumption (materialistic attitudes). Females displayed lower materialistic orientations than did males. Moore and Moschis (1981) conducted a study with adolescents to examine family and peer communication, and whether gender had any effect on materialism. The results indicated male had stronger orientation towards materialistic attitudes as compared to female. A study by Belk (1984) have proposed and tested three measures of materialistic traits: possessiveness, non-generosity, and envy. Exploratory data relating these traits to sex, age, and feelings of well-being were examined during the study, and the scores on the possessiveness, non-generosity, and envy scales were examined for relationships to subject sex. The results indicated that while possessiveness and non-generosity scores did not differ between male and female subjects, females were significantly less envious than males. On the basis of these previous research findings, the following hypotheses are developed for this study; Ho1: There are significant differences among the various age groups with regards to the type

of family communication patterns that takes place at home among young adult consumers in Malaysia.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

235 www.hrmars.com/journals

Ho2: There are significant differences between males and females with regards to the type of family communication patterns that takes place at home among young adult consumers in Malaysia.

Ho3: There are significant differences among the various age groups with regards to the development of materialistic values among young adults in Malaysia.

Ho4: There are significant differences between males and females with regards to the development of materialistic values among young adults in Malaysia.

Table 1.2: Summary of Major Findings Between Gender and Materialism

Author

Sample

Materialism Measure

Key Findings

Churchill and Moschis (1979).

806 adolescents from 13 schools in the U.S.

6 -items measuring materialistic attitudes.

Male exhibited stronger expressive orientation towards consumption (materialistic attitudes). Females displayed lower materialistic orientations than did males.

Moore and Moschis (1981).

784 respondents from 6th through 12th grade students.

6- items measuring materialistic attitudes.

The results indicated that male had stronger orientation towards materialistic attitudes as compared to female.

Belk (1984). 338 subjects across a variety of occupations.

3 -item measures of materialism; 9 items measuring possessiveness; 8 items measuring envy; 7 items measuring non generosity.

While possessiveness and non-generosity scores did not differ between male and female subjects, females were significantly less envious than males (means = 20.2 versus 22.5; p<.0001 via F-test).

Belk (1985).

338 subjects across a variety of occupations.

24 -items adapted from Belk’s (1984) materialism

A test for sex differences in materialism scores was non- significant at an alpha of 0.10.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

236 www.hrmars.com/journals

scale.

Achenreiner (1997).

300 children from the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, 7th, 10th grades. Specific ages targeted (8,12 and 16).

5 -items measuring materialism adapted from Richins (1987).

Male respondents, having a mean score of 14.21, were significantly higher in their materialistic values (p<.05), than female respondents, having a mean score of 13.35.

Methodology Sample And Procedures Materialism and family communication amongst various age group and gender were examined through a survey conducted in the Klang Valley in Malaysia between January to March 2011. The target population were college students in public and private institution of higher learning. College students were chosen because generally they represent the future of a country as with a good education, they will become middle-class professionals at least. The questionnaire was given to 1,200 randomly selected university and college students. Of which, 956 completed questionnaires were usable for the data analysis. Measures All of the constructs were measured by multiple items. Generally, the respondents were asked to indicate on a five-point scale the extent to which they agreed with the statements (1=Somewhat Disagree, to 5= Strongly Agree). Materialism. The key constructs were assessed using previously published, multi-item measures from Richins and Dawson (1992). A 15-item interrogative format was adapted from Wong et al. (2003) to measure materialism. The inter-item reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.69. The mean formed the measure of materialism, with higher scores indicating stronger endorsement of materialistic values. Family communication. It was operationally defined as overt interaction between parents and the child concerning goods and services (Churchill and Moschis, 1979). Socio-oriented family communication structure was measured with a 7-item measure, and was in line with previous research (Moschis and Moore, 1979a). The items measured the degree to which parents requested children to conform to parental standards of consumption. Concept-oriented family communication structure was measured in line with previous research conducted by Moschis and Moore (1984) and Moschis and Moore (1979a). It consisted of a 5-item measure. The inter-item reliability scores for socially-oriented and concept-oriented family communication

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

237 www.hrmars.com/journals

were 0.70 and 0.67 respectively. Religiously-oriented family communication structure was measured with six items adapted from Bindah and Othman (2012), in which parents sometimes say or do in their family conversations while their children were growing up. The inter-item reliability scores for religiously-oriented family communication was 0.728. Age variable was measured by asking respondents to indicate their year of birth. Findings Respondent Characteristics In this section, a general profile of the respondents is discussed. Table 1.3 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Basically, of the 956 respondents who completed the questionnaire, 39.9% were males and 60.1% were females. In terms of age distribution, 63.6% of the samples were between the aged of 20-29 years old, followed by aged range of 19 years old and below (25.4%) and the remaining of the respondents 11% were aged 30 years old and above. The higher percentage (63.6%) of respondents in the age group of 20 to 29 years old, were explained by the fact that the subjects for this study were young adult consumers, and were therefore the main target for response. In terms of ethnic group, the majority of the sample consisted of Malay respondents (52.2%), followed by Chinese respondents (28.2%) and Indians (10.7%) and other ethnic groups formed (9.0%) of the sample. The respondent characteristics in terms of ethnicity were generally consistent with the Malaysian Population Census (Department of Statistics and Economic Planning Unit, 2008). Consistent with the race composition of Malaysia, in terms of religious faith, the majority of the respondents endorsed Islam (58.2%), followed by Buddhism, (20.4%), Christianity (10.2%), Hinduism (9.4%) and others (2.0%). It was observed that more than two third of the responding sample were single (87.8%), while (11.3 %) were married. In terms of education, the majority of the respondent in the sample group possessed a professional qualification (56.9%), and (32.2%) possessed a college diploma while 10.6% have obtained their SPM certificate. The main reason for the high proportion of university degree holders in the sample was probably due to the characteristics of the urban population.

Table 1.3: Respondent Characteristics

Items

Frequency Percentage (%)

Gender

Male

Female

381 575

39.9 60.1

Age

below 19

20-29

243 608

25.4 63.6

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

238 www.hrmars.com/journals

above 30

105 11.0

Ethnicity

Malay

Chinese

Indians

Others

495 270 102 89

51.8 28.2 10.7 9.3

Religion

Islam

Buddhism

Hinduism

Christianity

Others

556 195 90 96 19

58.2 20.4 9.4 10.0 2.0

Marital Status

Single

Married

Widow/Widower/Divorcee

839 108 7

87.8 11.3 0.7

Educationa

Primary School or Less

PMR/SRP/LCE

SPM/SPVM/MCE

College Diploma

Professional qualification/University degree.

1 3 101 307 544

0.1 0.3 10.6 32.2 56.9

Note: PMR/SRP/LCE is equivalent to nine years of formal elementary and middle school education. Age Differences Between all the Constructs of the Study A one-way ANOVA was computed to compare the mean differences among the four age groups with all the constructs of the study. Table 1.4 presents a summary of the ANOVA results. Overall, there were significant associations between religiously-oriented family communication and age. The one-way ANOVA results showed insignificant association between materialism, socio and concept-oriented family communication and age. Age group differences in the socio-oriented family communication construct have been largely neglected. The researchers did not found any relevant research to support the present finding. Comparisons of findings between the present findings and the past research will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

239 www.hrmars.com/journals

Table 1.4: Age Differences Between All the Constructs of the Study

Constructs

F Sigb Group Comparison (Scheffe) <19

G1 20-29 G2

30> G3

Socio-Oriented Family Communication

3.32 3.27 3.41 1.935 0.145 Not significant

Concept-Oriented Family Communication

3.39 3.41 3.18 5.211 0.06 Not significant

Religiously-Oriented Family Communication

3.37 3.69 3.81 12.768 0.00 G3>G1 G2>G1

Materialism

3.62 3.49 3.56 3.001 0.05 G1>G2 G3>G2

Note: a higher scores represented greater agreement with the attributes; b Level of significance using one-way ANOVA; * The mean difference was significant at p < .05 Referring to Table 1.4, the present study found that age had no influence on the subjects’ socio-oriented family communication. From the existing literature, no research has looked into the association between age and socio-oriented family communication. Hence, comparison could not be made with regards to socio-oriented family communication and its association with age. The present study found that age had no significant influence on subjects’ concept-oriented family communication. Previous research has not explored the association between age and concept-oriented family communication. Hence, comparison could not be made with regards to concept-oriented family communication and its association with age. The present results found that age had an influence on the subjects religiously- oriented family communication. It was found that subjects in the age group of “30 years and above” were significantly scoring higher on religiously-oriented family communication compared to those in the age group of “less than 19”. No research has looked into the association between age and religiously-oriented family communication. Hence, comparison could not be made with regards to religiously-oriented family communication and its association with age. Although no prior studies have explored age differences and its effect on the various type of family communication that takes place at home, hypothesis 1 which stated that there are significant differences between young adult consumers’ age group and family communication patterns was supported.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

240 www.hrmars.com/journals

Lastly, the present study found significant age difference in the materialism construct. It was found that subjects in the age group of “19 years old and below” were significantly scoring higher on materialism construct compared to those in the age group of “30 years old and above”. Hence, hypothesis 3 which stated that there are significant differences between age and materialism was supported. This is consistent with previous studies which have found that age is a significant predictor of materialism. For instance Moore and Moschis (1981) conducted a study among respondents (N=784) from sixth through twelve grade students in the U.S, and found that age was a strong predictor of materialistic values (b=.14, p<.001). Younger adolescents tended to be more materialistic than their older counterpart. Similarly, Belk (1984) surveyed subjects (N= 338) across a variety of occupations, and found that two out of the three materialism measures to be significantly related to the age of the subjects. Envy showed a slight negative correlation with age (r= -.19, p<.0001) while non-generosity showed a slight positive correlation with age (r = .12, p<.02). The apparent decline in envy with age was estimated to be due to having achieved a greater proportion of one's material goals, having adjusted material goals to financial means, or having come to place less social importance on material goods. Other study conducted by Evrard and Boff, (1998) showed evidence of a number of significant relationships between the individual characteristics and materialism and attitudes toward marketing. Specifically it was found that acquisition and centrality (two component of materialism) diminished with age; this was interpreted as, that when age increases the importance of material possessions is relativized, for instance, substituted by family pleasures, but also that older persons have already acquired more possessions than people who are at the beginning of their professional life. La Ferle and Chan (2008) studied adolescents (N=190) in the age group of between 13 to 18 years old in Singapore. In the study age was the only demographic variable that showed a significant standardized beta value of -0.19 (significant at 0.05). Older adolescents were less materialistic than younger adolescents. Age together with imitation of media celebrities and perceived peer influence explained 40% of the variance in materialistic values. It was found that materialistic values decreased with age. Gender Differences Between All the Constructs of the Study The relationships between gender, materialism, socio-oriented family communication, concept-oriented family communication, religiously-oriented family communication constructs were investigated by testing the significance of the mean differences between male and female. The results in Table 1.5, showed that the mean differences between male and female were significant for concept-oriented family communication measure but no significant differences were found for socio-oriented family communication and religiously-oriented family communication.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

241 www.hrmars.com/journals

For socio-oriented family communication, the present study reported no significant gender difference in relation to young adults which stressed a socio-oriented family communication at home. Table 1.5: Gender Differences Between All the Constructs of the Study

Constructs Meana t-value Significanceb

Male Female

Socio-Oriented Family Communication

19.46 (3.24)

19.48 (3.24)

-0.075 0.321

Concept-Oriented Family Communication

19.78 (3.29)

20.64 (3.44)

-3.256 0.01*

Religiously-Oriented Family communication

17.91 (3.58)

18.26 (3.65)

-1.137 0.853

Materialism 14.05 (3.51)

14.20 (3.55)

-0.822 0.0 2

Note: a higher scores represented greater agreement with the attributes; b Level of significance using t-tests; c m marginally significant. * The mean difference was significant at p < .05

In terms of concept-oriented family communication, it appeared that male and female considerably stressed a different level of concept-oriented family communication at home. Specifically, young female adults were found to stress more on a concept-oriented family communication at home as compared to their male counterparts. No empirical studies have thus far examined gender differences with concept-oriented communication in the existing literature. Hence, comparison could not be made with regards to concept-oriented communication, and its association with gender. However, hypothesis 2, which stated that there are significant differences between gender and family communication patterns at home was supported. Referring to Table 1.5, in terms of materialism, it appeared that male and female had considerably different evaluations about the level of materialistic values. Specifically, young female adults were found to have a more positive attitude towards materialistic values than their male counterpart. This was consistent with a study by Cherrier and Munoz (2008) among mall patrons in Dubai which aimed to appreciate the differences and similarities between Arab and non-Arab consumers evolving together in a globalizing landscape. Their findings indicated that female had higher level of personal materialism in comparison to their male counterpart. Hypothesis 4 which stated that there are significant differences between gender and materialism was supported.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

242 www.hrmars.com/journals

Discussion And Conclusion The purposes of this study were to examine age differences in the various type of family communication patterns at home among young adult consumers in Malaysia. Secondly, to examine gender differences in the various types of family communication patterns that takes place at home among young adult consumers in Malaysia. Thirdly, to examine age differences in the development of materialistic values in Malaysia. And lastly, to examine gender differences on the development of materialistic values in Malaysia. This paper has also briefly conceptualized the family communication processes and review the literature to illustrate the association between the various type of family communication patterns that takes place at home and its relationship with materialism. The study was conducted in Malaysia, a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society. Materialism, socio-oriented, concept-oriented and religiously-oriented family communication were measured, assessed using previously published multi-item measures and the inter-reliability scores ranged from 0.67 to 0.70. Although no prior studies have explored age differences and its effect on the various type of family communication that takes place at home, hypothesis 1 which stated that there are significant differences between young adult consumers’ age group and family communication patterns was supported. Firstly, it was found that young adults age 30 years old and above tended to emphasise more on religious communication patterns at home in comparison to their younger counterparts in the age group of 19 years old and below, and those in the age group of 20 to 29 years old. Secondly, and importantly, this study has also found that young adult in the age group of 19 years old and below tended to be more materialistic than their older counterparts in the age group of 20 to 29 years old, as well as those in the age group of 30 years old and above. This result could also mean that as young adults move to various stages of their lifecycle; they tend to be less materialistic in comparison to their younger counterpart. This result was compared to other prior studies in other cultures in the findings section. Thirdly, this study also found that between males and females, females tended to stress more on concept-oriented family communication patterns at home, in comparison to their male counterparts. In other words, females tend to have more input in discussions at home as compared to their male counterparts. Finally, this study has found significant differences in terms of gender and materialism. It appeared that young female adults have a more positive attitude towards materialistic values than their male counterpart. Like in any study, this study has certainly its own limitations. First, this study has employed a scale to measure materialism but it has not been widely tested cross-culturally. Perhaps more established measurement scale which has been tested cross-culturally could be employed in similar studies in future research. In short and as a concluding remark, this present study was

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

243 www.hrmars.com/journals

an attempt to provide information which could be meaningful to help marketers to get a better understanding of their target consumers, particularly in terms of their values, on how various age group and gender tend to consume products and services. It is important to keep in mind that materialism as a value is directly related to consumption patterns of individuals. Bibliography Achenreiner, G. B. (1997). Materialistic Values and Susceptibility to Influence in Children. Association for Consumer Research, 24, 82-88. Belk, R. W. (1983). Worldly Possessions: Issues and Criticisms. Advances in Consumer Research, 10 (1), 514-519. Belk, R. W. (1984). Three Scales to Measure Constructs Related to Materialism: Reliability, Validity and Relationships to Measures of Happiness. Advances in Consumer Research, 11 (1), 291-297. Bindah, E.V. & Othman, M.N. (2012). The Effect of Peer Communication Influence on the Development of Materialistic Values among Young Urban Adult Consumers, International Business Research, 5(3), pp.2- 15. DOI: www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ibr/article/download/15348/10409 Bindah, E.V & Othman M.N. (2012). A Conceptual Model of the Determinants of Life Satisfaction Among Young Adult Consumers, International Business and Management, 4(1), pp. 28-36. DOI: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/ibm/article/view/j.ibm.1923842820120401.1088/pdf Bindah, E.V & Othman, M.N. (2012). The Impact of Religiosity on Peer Communication, the Traditional Media, and Materialism among Young Adult Consumers, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 2 (10).pp.480-498. DOI: http://www.hrmars.com/admin/pics/1233.pdf Bindah, E.V. & Othman, M.N. (2012). The Role of Religiosity in Family Communication and the Development of Materialistic Values, African Journal of Business Management, 6(7), pp. 2412-2420. DOI:http://www.academicjournals.org/ajbm/PDF/pdf2012/22Feb/Vincent%20and%20Othma n.pdf Bindah, E. V., and Othman, M.N. (2012). A Comparative Study of the Differences in Family Communication Among Young Urban Adult Consumers and the Development of their Materialistic Values: A Discriminant Analysis. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 1 (11), 142-156. DOI:http://www.arabianjbmr.com/pdfs/KD_VOL_1_11/9.pdf

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

244 www.hrmars.com/journals

Bindah, E. V., and Othman, M.N. (2012). An Empirical Study of the Relationship Between Young Adult Consumers Characterized by a Religiously-Oriented Family Communication Environment and Materialism. Cross-Cultural Communication, 8 (1), 7-18. DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020120801.355 Bindah, E. V., and Othman, M.N. (2011). The Role of Family Communication and Television Viewing in the Development of Materialistic Values Among Young Adults: A Review. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2 (23), 238-248. DOI: http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_23_Special_Issue_December_2011/29.pdf Burroughs, J. E., and Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and Well-Being: A Conflicting Values Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29 (3), 348-370. Carlson, L., and Grossbart, S. (1988). Parental Style and Consumer Socialization of Children. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (June), 77-94. Carlson, L., Grossbart, S., Stuenkel, K. J. (1992). The Role of Parental Socialization Types on Differential Family Communication Patterns Regarding Consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 1 (1), 31-52. Chaplin, L. N., and John, D. R. (2007). Growing Up in a Material World: Age Differences in Materialism in Child and Adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 34 (4), 480-493. Chan, K., and Prendergast, G. (2007). Materialism and Social Comparison Among Adolescents. Social Behaviour and Personality, 35 (2), 213-228. Cherrier, H., and Munoz, C. L. (2008). A Reflection on Consumers’ Happiness: The Relevance of Care for Others, Spiritual Reflection, and Financial Detachment. Journal of Research for Consumers, 12, 1-19. Churchill, G. A., and Moschis, G. P. (1979). Television and Interpersonal Influences on Adolescent Consumer Learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 6 (1), 23-35. Evrard, Y., and Boff, L. H. (1998). Materialism and Attitudes Toward Marketing. Advances in Consumer Research, 25, 196-202. Flouri, E. (2000). An Integrated of Consumer Materialism: Can Economic Socialization and Maternal Values Predict Materialistic Attitudes in Adolescents. Journal of Socio- Economics, 28, 707-724. Flouri, E. (2001). The Role of Family Togetherness and Right-Wing Attitudes in Adolescent Materialism. Journal of Socio-Economics, 30, 363-365.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

245 www.hrmars.com/journals

Ger, G., and Belk, R. W. (1999). Accounting for Materialism in Four Cultures. Journal of Material Culture, 4 (2), 183-204. Kasser, T. (2002). The High Price of Materialism. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., and Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic Values: Their Causes and Consequences. In Psychology and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World. T. Kasser and A. D. Kanner (Eds.). Washington, DC: American Psychology Association, 11-28. Kau, A. K., Kwon, J., Tan, S. J., and Jochen, W. (2000). The Influence of Materialistic Inclination on Values, Life Satisfaction and Aspirations: An Empirical Analysis. Social Indicators Research, 49, 317-333. Korten, D.C. (1999). The Post-Corporate World: Life After Capitalism. San Francisco, CA; United Kingdom: Berrett-Koehler. La Ferle, C., and Chan, K. (2008). Determinants for Materialism Among Adolescents in Singapore. Journal of Young Consumer, 9 (3), 201-214. McLeod, J. M., and Chaffee, S. H. (1972). The Construction of Social Reality. The Social Influence Process, 50-99. Moore, R. L., and Moschis, G. P. (1981). The Effects of Family Communication and Mass Media Use on Adolescent Consumer Learning. Journal of Communication, 31, 42- 51. Moschis, G. P., and Churchill, G. A. (1978). Consumer Socialization: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15 (4), 599-609. Moschis, G. P., and Moore, R. L. (1979a). Family Communication and Consumer Socialization. Advances in Consumer Research, 6, 359-363. Moschis, G. P., and Moore, R. L. (1979b). Decision Making Among the Young: A Socialization Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 6 (2), 101-112. Moschis, G. P., and Moore, R. L. (1984). The Impact of Family Communication on Adolescent Consumer Socialization. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 314-319 Moschis, G. P. (1985). The Role of Family Communication in Consumer Socialization of Children and Adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 1, 898-913. Newcomb, T.M. (1953). An Approach to the Study of Communicative Acts. Psychological Review, 60, 393-404.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences November 2012, Vol. 2, No. 11

ISSN: 2222-6990

246 www.hrmars.com/journals

Palan, K. M., and Wilkes, R. E. (1997). Adolescent-Parent Interaction in Family Decision Making. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 159-169. Reimer, B., and Rosengren, K. E. (1990). Cultivated Viewers and Readers: A life-style perspective. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Richins, M. L., and Dawson, S. (1990). Measuring Material Values: A Preliminary Report of Scale Development. Advances in Consumer Research, 17, 169-175. Richins, M. L., and Dawson, S. (1992). A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19 (3), 303-316. Rose, G. M. (1999). Consumer Socialization, Parental Style, and Developmental Timetables in the United States and Japan. Journal of Marketing, 63 (July), 105-119. Sheldon, K. M., and Kasser, T. (2001). Getting Older, Getting Better: Personal Strivings and Psychological Maturity Across the Life Span. Developmental Psychology, 37, 491-501. Ward, S. (1974). Consumer Socialization. Journal of Consumer Research, 1 (2), 1-14. Wong, N., Rindfleisch, A., and Burroughs, J. (2003). Do Reverse-Worded Items Confound Measures in Cross-Cultural Consumer Research? The Case of the Material Values Scale. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 72-91.