African Astronomy

-

Upload

parag-mahajani -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of African Astronomy

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

1/10

tiquity, BritishPergamon Vistas in Astronomy. Vo\. 39, pp. 529-538,1995Copyright 1996Elsevier Science Ltd

Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved0083-6656/95 $29.00est Ireland.26), inpress.recumbent

urnai for the

the History of: Prominent

ject (2):Thent to Journalvisibilityand

Informatiollndale, IL,inple viewshedrthern Mull.Archaeology,Press,omy. In: As-University

ty in Britain, Oxford.to archaeoas5-177. Group

36, 311-

Oxford.Pa st P ercep-M. Ronayne

0083-6656(95)00008-9

Stars and Seasons in Southern AfricaK. V Snedegar a

Department of Astronomy, University of Cape Town, Republic of South Africa

Abstract: Although the indigenous people of Southern Africa traditionally viewed the sky as a place quite apart from the Earth, they believedcelestial phenomena to be natural signs united with those of the Earth ina harmonious synchronicity. There is no substantial evidence that the precolonial Africans imagined a casual relationship between celestial bodiesand the seasonal patterns of life on Earth. They did, however, recognize acoincidental relationship. The traditional African cosmos, then, worked asa noetic principle unifying the observed motions of celestial bodies, the sequence of seasons, and the behavior of plants and animals. Such a cosmos,with local peculiarities, was widely understood in Southern Africa beforethe end of the last century. By the early 20th century European colonialparadigms had largely obliterated this African worldview.This paper willoffer a partial reconstruction. Pre-colonial South African people viewedtime as a sequence of discrete natural events; through annual repetitionthese events served as a guide for proper human action. The South Africansanalyzed the passage of time in terms of the motions of celestial bodies, thematuration of beneficial plants, and the mating patterns of animals. Therightful course of human life was seen to fit within the seasonal context ofthese natural phenomena. The visibility of conspicuous stars and asterismsmarked significant times of year. For instance, the Lovedu people greetedthe dawn rising of Canopus with joy: "The boy has come out." The starwas a signal for rainmaking and boys' initiation ceremonies to proceed. TheVenda constellation Thutlwa, the giraffes,comprises 0( and 13 Crucis and 0(and 13 Centauri. In October Thutlwa skims the trees of the evening horizon. The Venda Thutlwa literally means 'rising above the trees,' an allusionto the majestic vegetarian creatures and the stars advising the people to bedone with their spring planting. This paper will describe stellar associationswith other creatures: wild dogs, warthogs, wildebeests, swallows, cuckoosand cicadas. In each case the visibility of a star will synchronize with a behavior of the associated species.Together, stars and species informed manof the order and unity of an African cosmos - a worldviewthat must havebeen as satisfying as it was beautiful.-Current address: Utah Valley State College, 800 West 1200South, OREM, UT, 84058-5999, U.S.A. The researchiorthis paper was made possible by an award of a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Cape Town; thisauthoris particularly grateful for the advice and support of Dr Brian Warner, professor of astronomy at UCT.

529

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

2/10

>ri.~~*f,'~~?'~

2. THE SEASONS

Few experiences can be more inspiring than that of a starry night out in the African bu hwhere Nature's primeval splendor embraces the imagination as well as the senses, Here tSh'night comes alive. The sharp, lightly scented air drones with an hidden orchestra of COuntle,emating insects. A distant counterpoint of bird chatter, the arguments of baboons, the hvena',slaughter, suggests both the great amount of nocturnal activity and how little of it we d;rectl~perceive. Above these restless creatures of the night the stars keep watch like the glistening e\~Sof half-remembered ancestors, and the Milky Way arches across the sky like some phant~mpathway to another existence.The mythic potential of celestial objects fully exercised the minds of indigenous South

Africans, but that rich heritage is not to be the theme of this paper. It is less well knownto modern scholarship that pre-colonial Africans also viewed the sky as a natural resourcejust as available for exploitation as were the Earth's animal, vegetable and mineral resources.The particular utility of the heavens lay in their regular apparent motion. By acquaintingthemselves with celestial motion in a very general innumerate way the Africans were able t;correlate the changing positions of heavenly bodies with seasonal changes on Earth. In short.the Africans developed rudimentary calendars. This paper will briefly discuss how certainstars and asterisms helped South African people define temporal locations within a seasonalframework. Special attention will be paid to the traditions of the Nguni (Swazi, Xhosa. Zulu!and Sotho-Tswana people. For a good introduction to the ethnology of the region the readershould consult the Oxford History of South Africa (Wilson and Thompson, 1969, 1971).

K. V Snedegar

5301. INTRODlJCTION

With the exception of the Western Cape area, Southern Africa lies in a climatic regiontypified by summer rainfall and winter aridity. The rainy/dry season dichotomy was of greatsignificance to pre-colonial agriculturalists as they depended entirely on rainfall as a sourceof water, irrigation being unknown to them. Nonetheless, South Africans recognized morethan two seasons. Some people counted up to six; three was a more common number. Thenomenclature of these seasons varied widely, but the Northern Sotho terms Marega, Selemo.and Lehtabula are not extraordinary in their implications. Marega, "when things dry up.'extends roughly from May to August, winter in the southern hemisphere, Selemo, "the diggingseason," commencing with the spring rains, is time for cultivation, planting and weeding. Thepeople reap what they have sown during Lehlabula, "the time of plenty," concluding aboutour month of April. The seasons themselves only acted as a vague conceptual template forrecognizing the annual sequence of generation and corruption among the Earth's flora andfauna. On a practical level the most certain guide was always the presence or absence ofrain.life blood of all African creatures. However, for ritual and symbolic purposes the changingvisibility of notable celestial objects had special significance. ,Despite Keletso Atkins' brilliant chronicle of the African devotion to observing synodICmonths, The Moon is Dead! Give Us Our Money! (Atkins, 1993), our understanding of the

actual workings of Southern African lunar calendars remains incomplete. Chaotic iists atmonth names, none in much agreement with any other, await the unhappy investigator whoenters this field. Punctuating this gloom with flashes of light are African traditions concernIllgspecific objects of the starry sky. These include Canopus, the Pleiades, Orion, Spica, th~Southern Cross, and the Milky Way; together they provide us with considerable insight Illkthe meanings with which Africans invested their seasons as well as their lunar months.

,JJ"'i;~",:~~"I,;11;

I, "\

\ ,.i Ii ' ~iM

,j~ I',;:lt~i,r~~l

. "~~~

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

3/10

3. CANOPUSStars and Seasons in Southern Africa 531

It in the African bushLS the senses. Here th~orchestra of countless)f baboons, the hyenas'N l itt le of it we directlyL like the glistening eyes,ky like some phantomls of indigenous Southr. It is less well knowny as a natural resource: and mineral resources.notion. By acquaintingle Africans were able tonges on Earth. In short,:fly discuss how certainations within a seasonalmi (Swazi, Xhosa, Zulu)of the region the readermpson, 1969, 1971).

lies in a climatic region1 dichotomy was of greatly on rainfall as a source\fricans recognized more.re common number. The10 terms Marega, Selemo,a, "when things dry up,"here. Selemo, "the diggingJlanting and weeding. Theplenty," concluding aboutLeconceptual template forlOng the Earth's flora and,resence or absence of rain,lic purposes the changingtion to observing synodicour understanding of thecomplete. Chaotic lists ofunhappy investigator whoican traditions concerningleiades, Orion, Spica, theh considerable insight intotheir lunar months.

The Sotho, Tswana and Venda people traditionally knew Canopus, the second brighteststar in the night sky, as Naka or Nanga, "the Horn Star." For the Zulu and Swazi it wasinKhwenkwezi, Khwekheti to the Tsonga, simply meaning "brilliant star." The Zulu poet MazisiKunene (1981) described inKhwenkwezi as one of the morning stars which help people determine time. Nkwekweti is the fifth month of the traditional Swazi calendar; iNkwekwezi is amonth name sometimes used in the Mkuze region of Zululand. The term U-Canzibe (Xhosa)or uCwazibe (Zulu) meaning 'shining' or 'sparkling,' was also applied to Canopus. McLaren(1929) identified U-Canzibe as Canopus seen rising before daybreak in May. However, in hisZulu dictionary Bryant (1940) registers Ucwazibe as Aldebaran; Doke and Vilakazi (1964)second this opinion. The confusion may derive from reports such as from James Stuart's informants, who described uCwazibe as the very first star of the group that make up the Pleiades.This statement would seem to favor an identification with Aldebaran. On the other hand, theinformants said that the appearance of this star was taken as the actual beginning of the newyear, which supports identification with Canopus. They add: "But there is a dispute aboutwhich star is uCwazibe" (Webb and Wright, 1976-1979, vol. 3, p. 167). Norton (1909) believedthat his Zulu guides were pointing to Fomalhaut as uCwazibe; he was certainly wrong. A termused only by the Zulu in Natal, as opposed to Zululand proper, is Andulela, 'The Harbinger,'was a name given to a morning star rising at harvest time: this is undoubtedly Can opusuCwazibe, or 'praise-poetry,' occasionally alludes to Canopus. A praise poem hails the Ndebele king Mzilikazi as "the tall conspicuous early morning star in the south-east precedingthe constellation Pleiades." A praise of Swazi king Sobhuza I includes the line: Amakwezi kubike/and inkwenkwezi kanye neSilimela ("the stars tell each other which is the Morning Star,and the Isilimela;" Vail and White, 1991, pp. 105, 184). The association of this morning star,inkwenkwezi, with the Pleiades has to do with its role in establishing the seasonal calendar.The star's rising in the southeast likewise indicates that it is Canopus.The calendrical significance of Can opus is more clearly discerned among the Sotho-Tswana

people than with the Nguni. Naka was said to break up the year and to burn up anything greenin nature as it heralded the winter season and the browning of the veld. NakalNangalCanopusshould be visible in the pre-dawn sky by the third week of May. Among the Venda the firstperson to see Nanga at that time of year would sound the phalaphala horn from atop a hill.He would receive a cow as a prize. The Lobedu considered the first pers.on to view Nakaas having good luck. Upon learning that Naka had been spotted the people would chant,"Naka has come out, the boy has come out" (Krige, 1931). The star's dawn rising was a signalfor rainmaking ceremonies to proceed; it also had some connection with the Wolika boys'initiation ceremony. Beyer (1919) maintained that every year the Sotho carefully watched forNaka toward the end of May. Like their Venda counterparts, Sotho chiefs awarded a cow forthe earliest sighting of Naka. On the day of the sighting the chiefs would call their medicinemen together. Throwing their bone dice, the doctors would judge whether the new seasonwould be favorable or not. A Native Commissioner of Sekhukuneland gave this account ofthe Northern Sotho tradition:

"For the Basotho of the Northern Transvaal the year begins during the month ofNaka (Canopus). During the days when the rising of the star is expected, all themen of the tribe leave their homes and camp out on the mountains. Sometimesthey arise very early and arriving on the mountains they kindle fires and watch theskies to the South, where the star is expected to make its appearance. It is the beliefof all the men that the person who is the first to see the star will be very prosperousduring that year. He will have a rich harvest of kaffir corn, and will enjoy good

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

4/10

532 K. V. Snedegar

~iJlI~~"

/ )1!')( ');\;I~,\{ ;,~)t)jl

iA~,,1-illJIll'

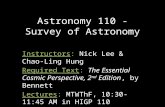

Fig. I. A Pedi (Northern Sotha) man blowing a phalaphala horn (photo courtesy of theMcGregor Museum, Kimberley, South Africa).

luck and good fortune till the end of his life. On the day following upon the risingof Naka, the men of the divining bones, the doctors, go to the rivers early in themorning to wash their bones. They put their bones into water that is perfectly still,in which the color of the bones will show up clearly. By understanding the colorof the bones, they can foretell what kind of year is expected, a year of plenty orof famine or misfortunes" (Franz, 1931, pp. 241-242).

4. THE PLEIADESThe Africans have a particularly strong tradition of observing the Pleiades. Some people

viewed the cluster as a group of six or seven stars, one Shona name for them being Chimu-tanhatu, simply 'the six,' another Chinyamunomwe, 'the seven.' Other people were uncertainabout the number of constituents. A Venda riddle asks: "I counted which stars and had togive up?" The correct reply is "the Pleiades." Stayt (1931) reports that the Venda discernedonly six stars. A Shona term, chirema, meaning 'lame' or 'abnormal,' is also applied to the

cluster, suggesweanjournalistawaiting a timleavethe homVon Sicard

the Pleiades iKi/imia, 'theand by implicathe Digging Sweather." 1 Ainthe Sun's glvu/i rains comthe masika raithey herald apeople, the obEastern, Centrwith local weaknew the starscall them Tshiand Zulu, isiLVon Sicard finrender isiLimelcultivating impAccording tOne of James

for the clusterthe end of thebefore the endthe Digging Spractice. LateAt this time oare months inAt first blush

he s peaks of a". .. dcominuntilthe sand

If the informnothing is gainZululand, mentoward the begagricultural prThe Pleiades m

~verb hcentury:Dr Guyteachingat the U

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

5/10

urtesy of the

ng upon the risingrivers early in theat is perfectly still,standing the coloryear of plenty or

eiades. Some peoplethem being Chimuople were uncertainich stars and had tothe Venda discernedalso applied to the

, Stars and Seasons in Southern Africa 533

j cluster,suggesting that the Pleiades were seen as an unnatural conglomeration. The Zimbab,,,,0journalist 1.Gaudari described the cluster as,small stan h~ldby au uuknown attractionawaitmga tIme when they could fall away to an mdependent hfe as do chIldren when theyi leavehe home (McCosh, 1979, p. 35).VonSicard (1966)considered it likelythat Arab traders introduced the tradition of observingthePleiades in a calendrical sense to the Swahili. In Kiswahili the Pleiades are known asKilimia, ' the Digging Stars.' Referring to the vuli and masika rainy periods of East Africa,andby implication the cultivating seasons associated with them, a Swahili proverb runs: "IftheDigging Stars set in sunny weather they rise in rain, if they set in rain they rise in sunnyweather."I As viewed during the evenings from equatorial East Africa the Pleiades disappearinthe Sun's glare, they 'set,' about early May, to re-emerge in the morning skyjust as the Junevuli rains commence. Observed in the morning sky the Pleiades set at dawn toward the end ofthemasika rainy season in November; when they are seen to be rising in the evening twilighttheyherald a dry or sunny period (Gray, 1955).Widely dispersed by the migration of Bantupeople,the observation of the Pleiades' rising and setting became commonplace throughoutEastern, Central and Southern Africa. Interpretation of these events varied in accordancewithlocal weather patterns, but the general tradition was so strong that many African peopleknewthe stars by the same title. For the Nyasa of Malawi the Pleiades are Lemila; the Vendacanthem Tshilimela; the Karanga, Chirimera; the Tsonga, Xirimelo; Sotho-Tswana, Selemela;andZulu, isiLimela. Stayt derives the Venda Tshilimela from the verb u lima, 'to plough.'VonSicard finds the Shona root -rima, meaning 'to till, cultivate or hoe.' Zulu dictionariesrender isiLimela as 'the Digging Stars,' also implying hoeing (the hoe had been the principalcultivatingimplement in Southern Africa before the introduction of the plough by Europeans).According to oral tradition the Zulu wereactivelywatching the isiLimela in the 19th century.Oneof James Stuart's Zulu informants named Dhlozi commented that the best time to lookforthe cluster was about an hour before sunrise and that the stars should be visible towardthe end of the month uluTuli. That is to say, good observers should have seen the isiLimelabeforethe end of June each year. But there is a problem. Watching for the heliacal rising oftheDigging Stars and following their dictates in June does not accord with Zulu agriculturalpractice.Late June, being the middle of winter, is scarcelyan appropriate time to begin hoeing.Atthis time of year the land is brown, the soil dry and hard; the life-restoring spring rainsaremonths in the future.At first blush, one of Henry Callaway's informants only seems to add to the confusion when

hespeaks of a Zulu observational tradition. He relates that the star cluster". .. dies, and is not seen. It is not seen in winter; and at last, when the winter iscoming to an end, it begins to appear - one of its stars is first, and then three,until going on increasing, it becomes a cluster of stars, and is perfectly clear whenthe sun is about to rise. And we say /silimela is renewed, and the year is renewed,and so we begin to dig" (Callaway, 1970,pp. 399-400).Ifthe informant is referring to the Pleiades' morning visibility and he does mention sunrise

nothing is gained; but our picture changes if he is actually referring to evening visibility. FromZululand, men retiring late after a beer-drinking party can see the Pleiades rising at midnighttoward the beginning of September. The late evening interpretation is consonant with Zuluagricultural practice because the first spring rains could reasonably be expected in September.ThePleiades may have provided a rule of thumb, but their visibility did not strictly determine

I This proverb has impressed itself so deeply in the Swahili memory that it is sti ll being recited in the late 20thcentury: Dr Guy 1.Consolmagno, SJ., now of the Vatican Observatory, recalls hearing the proverb when he wasteachingat the University of Kenya.

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

6/10

~~.ff'l~fi-;,'j'Nl-'J"'t'r:llMiK,:IiHIIMtm@dl . J~p.",>-",m, .,.,. lil~ j .. .J .1t.llIllMln~~"f1'~

5. ORION

6. THEW

While thDictionarystellation sathe larval foZimbabwecaterpillars1972). Mopsummer emkgala stars.time in Juneof the caterpthe veld.

yand e Tafull century,khweg=ei !Mungombaand a buckare pibwe nof transmissAnothercestars of OriBetelgeuse,Magakgalain the earlyfor the root(I) an edib(2) the conlore co

Ingongolion Star-LoreThe articleto be directl(1927). TheThis star is"... which rwhat time oA somew

(1964) identhe name olngongoni mwildebeestswildebeest(Connochaealmost all t

K V Snedegar34

The stars comprising Orion's Belt and Sword formed asterisms in the minds of SouthAfricans. The Zulu sometimes called the three belt stars imPhambano, which possibly comesfrom the root mbambane, a cluster or group of things close together. Ritter (1955), however.presents the term as Impanbana, and interprets it as 'the Crossing.' He adds that the Zuluobserved the heliacal rising of Impanbana in July, after which cultivation would begin. To theXhosa the asterism was amaRoza, signifying nothing more than 'three stars in a row.' TheKaranga knew the asterism 8, E, and" Orionis as Nguruve, 'the wild pigs.' This designation waswidespread. For the Sotho they were the Makolobe, for the Tswana, Dikolobe, both meaning'pigs.'In the Mkuze area of northern Zululand one of the summer months was occasionally

called iNgulube ukuzala kwayo ('the moon when the wild pig litters down'). One would liketo think that the wild pig appellation results from a calendrical analogy with the reproductivebehavior of these animals. Some ambiguity of species exists; either the warthog, Phacochoerusaethiopicus, or the bush pig, Potamochoerus porcus, could be indicated. Fortunately, the twospecies exhibit very similar behaviors. Fairall (1968) investigated the reproductive seasons ofmammals in the Kruger National Park. He found that the warthog has a farrowing seasoncommencing in mid-November. Research on the bush pig shows that it has its litters in thesame period. The Dikolobe stars have their acronychal rising one could say that they are beingborn about the third week of November. To have associated the reappearance of the stars withthe appearance of new pigs must have been only natural. Intriguingly, bush pig and warthoglitters often consist of three piglets (Smithers, 1971). If the Africans recognized this fact itwould have given them another reason to identify the three Belt stars with pigs.Two or three celestial dogs, called Mbwa in the Shona language, were closely associated with

the wild pigs. Von Sicard was inclined to equate one dog with Sirius, but the Tswana pointto Orion's Sword, saying: dintsa Ie Dikolobe ('the dogs are chasing the pigs'). The NorthernSotho cognate Dintshwa is likewise applied to the sword stars. That the motif of these starschasing or hunting each other was current among diverse African people may offer evidenceof the transmission and transformation of folk information in Africa. The Ju/Wasi tell of thegod, Old /Gao, who was hunting in the skies. He spotted three zebras, the stars of Orion's Belt,and shot an arrow at them. But it missed, falling short. The arrow is Orion's Sword. All threezebras escaped onto the Earth, as can be seen when they set in the west (Marshall, 1975). In aKhoikhoi myth preserved by Hahn (1881, pp. 108-109), the Aob is sent out by his wives, thePleiades. He too stalks the zebras. Hahn depicts Aob in this way: Aldebaran represents Aobhimself; the stars rr! and rr2 Orionis comprise his bow; 8 and E Tauri are his sandals, //haron;

the season of cultivation. Rain was all important. Whether or not the stars agreed, the peOPlewould only take up their hoes and begin cultivation after the first rains.While the Zulu may have linked the Pleiades' evening visibility with agricultural activity, the

Xhosa had a different understanding of the asterism's morning visibility. The Xhosa watchedfor the first appearance o~ the isiLir:ze/~ in June. It is ~aid that the m?nth of the DiggingStars, Eyesilimela, symbobzed new bfe rn man for the time of the comrng-out ceremony ofthe abakwetha circumcision school was determined by the appearance of this constellation. Ithas always been the custom for Xhosa men to count their years of manhood from this date(Hodgson, 1982, p. 53). When praising the handsomeness of chief Kaiser Matansima, the poetYali-Manisi naturally adds the formulaic line: "Even from afar he's beautiful as the Pleiades"(Opland, 1983, p. 115).

~.l..J....,.ljL..l~tIlrMlI

(i~~~ii~" i"""".I')

~, ", I'," 1i1i!\; j~,\~ ','1tt

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

7/10

6. THE WILDEBEEST STAR

While the Delphinus connection is difficult to accept, the Comprehensive Northern SothoDictionary (Ziervogel and Mokgokong, 1975) seconds the entry on edible worms and a constellation said to appear on cold nights. The caterpillar is most likely the famous mopane worm,the larval form of Gonimbrasia belina, the Anomalous Emperor moth. Throughout Botswana,Zimbabwe and the Northern Transvaal people collect mopane worms by the sack-full. Thecaterpillars are eviscerated and sun-dried or roasted, then added to stew as a relish (Pinhey,1972). Mopane worms themselves emerge twice a year, in summer and again ,in winter. Thesummer emergence occurs about the time of the acronychal or evening rising of the Magakgala stars. As for the cold nights, it is said among the Northern Sotho that after threshingtime in June these stars despoil all green plants. This description is in keeping with the actionof the caterpillars although they only defoliate mopane trees as well as the winter browning ofthe veld.

lngongoli was one of the few Xhosa star names mentioned in an anonymous article, 'Noteson Star-Lore,' appearing in the October 1881 issue of the Cape Quarterly Review (WG., 1881).The article equates Ingongoli with the Evening Star, presumably Venus. The term would seemto be directly related to a Tsonga name for Venus, Ngongomela, which was collected by Junod(1927). There is, however, reason to believe that the term refers to a fixed star, not a planet.This star is possibly Spica. Zulu informants told Samuelson (1929) of a bright star, iNqonqoli," ... which rises at about 3 a.m. before the morning star." Unhappily, Samuelson did not recordwhat time of year the late-night rising takes place .A somewhat abbreviated form of Samuelson's lnqonqoli is iNonqoyi. Doke and Vilakazi

(1964) identify Inonqoyi as the planet Jupiter. But after the pattern of other stars bearingthe name of a lunar month, an association between Inqonqoli/lnonqoyi and the Swazi monthlngongoni may be inferred. Ingongoni, meaning 'wildebeest,' is the summer month when thewildebeests calve; Mkhuze Zulus knew this month as iNkonkoni. Further, it is noteworthy thatwildebeest herds are highly synchronized in their reproduction. A study of the blue wildebeests(Connochaetes taurinus) of Kruger National Park found that under normal circumstancesalmost all the animals had their young within a 6 week period commencing in mid-November

535tars and Seasons in Southern Africay and e Tauri form his kaross or coat. The stars e, l, and 42 Orionis form Aob's arrow. Afull century after Hahn's account /Gwi Bushmen described stars in the vicinity of Orion askhweg=ei !ui, or 'a man shooting a steinbok' (Silberbauer, 1981). During an interview, LouisMungomba of the !Xu community at Schmidtsdrift spoke of the Belt stars as a man, his doganda buck (Mungomba, 1994). As far away as the Songye people of central Zaire the Belt starsarepibwe na mbwa na nyama ('a man, a dog and an animal,' Merriam, 1974). The mechanicsof t ransmission of the chase motif among disparate people has yet to be elucidated.Another celestial entity, possibly a rather extended asterism, may have included the brightest

stars of Orion. Beyer (1919) suggests that the Sotho recognized a foursome of stars - Rigel,Betelgeuse, Sirius and Procyon - which all together they called Magakgala. The stars are alsoMagakgala to the Tswana, who say the corn should be harvested when Magakgala is visiblein the early evening. In his Setswana dictionary, Snyman (1990) lists two intriguing definitionsfor the root word -gakgala:(l) an edible caterpillar, and(2) the constellation of the dolphin (i.e. Delphinus; however, the Tswana have no traditional

lore concerning dolphins).

ars agreed, the people

in the minds of SouthJ, which possibly comesRitter (1955), however,He adds that the Zuluion would begin. To thetree stars in a row.' Thegs.' This designation wasDikolobe, both meaning

~ricultural activity, they. The Xhosa watchednonth of the Diggingming-out ceremony of;)f this constellation. Itanhood from this date:r Matansima, the Poetlutiful as the Pleiades"

nonths was occasionallydown'). One would like19ywith the reproductiveIe warthog, Phacochoerusted. Fortunately, the twoe reproductive seasons ofg has a farrowing seasonlat it has its litters in thelId say that they are beingpearance of the stars withgly, bush pig and warthoglUS recognized this fact itlfS with pigs.'ere closely associated with-ius, but the Tswana point~the pigs' ). The Northern.at the motif of these starspeople may offer evidenceica. The Ju/Wasi tell of thes, the stars of Orion's Belt,is Orion's Sword. All threewest (Marshall, 1975). In as sent out by his wives, theAldebaran represents AobUri are his sandals, /lharon;

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

8/10

______________________ '_'h.''',,''I,.,I' '''~ 1 liwiW. . . . .

536 K. V Snedegar

~ ..,.,,-

'~I

(I.' i'!.~1II

+ I'll" J~I\( '~ll~11\UR ~'l, ~I

(Fairall, 1968). Research on unmanaged wildebeest populations of the Serengeti has shownthat on average 87'Yt, of calves are born within a 20-day period in non-drought years (Sinclair1977). Observing the spectacle of thousands of animals having their young at the same tim~must have been sufficient reason for the Swazi and Zulu to call the lunation correspondingroughly with November/December the 'Wildebeest Month.' As for a Wildebeest Star whichrises at about 3 a.m., the timing could not be more opportune - as seen from northernZululand, Spica rises shortly before 3.30 on the morning of 15 November, and about 1.30 on15 December.

7. THE GIRAFFE STARSThe Sotho and Tswana recognized a group of stars called Dithutlwa, the giraffes. Thuda is

the Venda equivalent. Normally there are four giraffes, two male and two female. Sometimesthe Venda add a little giraffe, thudana. In Tswana parlance the males are the brighter stars, C(and f3 Centauri, while exand f3 Crucis are the females. The Sotho and Venda, however, makeex and f3 Centauri the females. According to Stayt (1931), the Venda month Khubvhumedzirightly began with the crescent Moon when the lower two Thuda are just below the horizonand the upper two are just visible. For the Sotho, when the Dithutlwa are seen gliding abovethe southwestern horizon just after sunset, they indicate the beginning of cultivating season.Late in May the females leave the company of the males, dipping to the pre-dawn southwesternhorizon (Crux is circumpolar below 2r South Latitude) and then pulling up Naka/Canopus.The Sotho-Tswana term Thutlwa is itself suggestive of the horizon-skimming stars. It meansabove the trees. Perhaps in a related strain, the Tswana informant Mogorosi speaks of twodepabe, 'yellow animal' stars found in the south: in winter they cross each other and one comesto settle where the other was before. The bigger star is a sign of the winter season and theother is a sign of the summer season (Breutz, 1969, p. 208). This is consistent with the motionof the giraffe stars. At all events, giraffes have no monopoly on being yellowish in color. The/Xam Bushmen knew these stars of Centaurus and Crux as lions. Apparently the Tswana wereaware of the Bushman tradition, but decided to transform the lions into animals whose tallfeatures lifted them closer to the stars.

8. THE MILKY WAYThe Zulu called our galaxy umTala or umThala. Doke and Vilakazi (1964, p. 782) registerfour other definitions for the term:(1) a species of tall marsh grass, Erianthus capensis, used for thatching,(2) the strip of fleshy muscle encircling the paunch of cattle,(3) a dark stripe on some people from the navel down, and(4) the patch of hair left on top of an infant's head when the rest has been rubbed off.For the Xhosa the Milky Way was Um-nyele, meaning the raised bristles along the back [of

the sky], as on an angry dog (Soga n.d.). Judging from these associations, the Nguni peoplemust have viewed the Milky Way as a king of fuzzy rib-vault across the night sky. The ideathat it held up the sky, or even held it together, is strongly implied. One of the many titles ofthe Swazi king, the chief pillar of traditional Swazi society, is 'The Milky Way' (Kuper, 1986):and a Zulu regiment enrolled by king Mpande bore the nickname umtala wezulu (Faye, 1923).

The Sothobirdrests. Theofheaven,' thepurpose of Moandnight. Sevconstant moveEvidently, t

a /Xam informdepicted the 'Stheother is ovWay,pictureddry places. ' ASerogabolo alsswear,curse otoClegg (1986thisdescriptionofthe Galaxy,quiteoften delforthe Tswanaunfulfilled.

9. CONCLHSouth Africa

supposed naturMilkyWay. It wThestars of Opigs,the emergheralded the aritual one a titime did thesewewould be mAfricans' keenrelationships b

References

[I] Atkins, K.African W

[2]Beyer, G.[3]Breutz, P.ies in Hono[4] Bryant, A[5] Callaway,[6]Doke, C. MUniversity

-

7/29/2019 African Astronomy

9/10

~Stars and Seasons in Southern Africa 537

ti has shown:ars (Sinclair,le same til11eJrrespondingit Star whichom northernlbout 1.30 On

dIes. Thuda isIe. Sometimesghter stars, c