Adec Preview Generated · 2012. 8. 17. · ately 20 km from Wolgan Gap. The width of the valley...

Transcript of Adec Preview Generated · 2012. 8. 17. · ately 20 km from Wolgan Gap. The width of the valley...

-

ll-IE WOLGAN VALl£Y

A study of land-use and c

with proposals for future

onflicts

management.

V LlTHGOW REGIONAL LlBRAR BS.·/_".V. ~.(~ Ifc... 11- ( }f I $ r: 0(' ~7 ~ 8,

'WoL 'Bt

-

I I I I I I I I ,I I I I

I I I I I

';'1 I ,'"

This study was prepared for The National Trust of Australia (New South Wales) by Ro1and Breckwo1dt with the assistance of a grant provided by the

. Austral ian Government under the National Estate P rog ra,mme.

Published by

The National Trust of Austral ia (N.S.W.) Observatory Hill, Sydney. N.S.W. 2000

October, 1977.

c. The National Trust of Australia (N.S.W.)

National Library of Australia Card Number & ISBN 909723 62 1

1 ~ I \ :

t i \' ! I ! I'

; ,; ,

I 1

, j

i "

,/,

-

Most people who have been there feel strongly about the Wolgan Valley. Few places contain such a diversity of attractive attributes in such close proximity. The list is formidable - natural beauty, the glow-worm tunnel, a fasci~ating history, recreation areas, agricultural lands, minerals and wjldernes.s .. _A]1.~are·_c_ontaineJi in.a_val·ley .. _ ringec(bya spectacular sandst6~eescarpment .... ft is . -becaus.e of these attributes·and differing perspectives on how they should be used that conflicts have arisen.

The Wolgan Valley is characterised by a number of land-use conflicts. Indeed, few of the pressures which come to bear on rural lands are absent from the valley. Its proximity to Sydney and the Bathurst Orange growth centre.will ensure that thes~ problems wi 11 not diminish without careful planning and subsequent management.

The interest groups associated with the valley agree that all is not well. Nor is this only the view of those who visit the area. The residents are not entirely happy. Most of them are farmers who wish to pu~sue their livel i-hoods in the absence of an influx of visitors who may hold values alien to their own and who may also want to ~se their lands. It is, however, a curious situation because many people want the Wolgan Valley to stay as it is .. They are fearfu 1 that State Government i ntervent ion may change the area in more ~etrimental fashion than the present unre~olved conflict situation. On the other hand, they agree that the pressures of modern society will not allow the Wolgan to stay the same without intervention.

It is for these reasons that this study has eVQlved. The funds for the study were granted by the Australian

_ Government under the 1 975-·7-6-Na-tional· Estate Programme to the N.S.W. Planning and Environment Commission. The Commission handed over the responsibility for preparation and administration of the study to The National Trust of Australia (New South Wales).

... . -

'.

I j l '11 JI

·1 ! I I

·1 ! !

I 'I I

.1 I

1I I .~; · .. ·11 w

jl .M

:1 ,I '1 I

.1 I I 'I II

! I. J

-

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

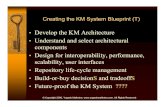

CHAPTER I 1.1 1.2

CHAPTER 2 2. I 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.(>

CHAPTER 3 3. I 3.2

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER

. '.

4. I 4.2

5 5. I 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5. 10 5. 11

CHAPTER 6

Background Scope of Study

CONTENTS

Description of the Wolgan Valley

The P~ysical Environment Geology Geomorphology Soi Is Climate Vegetation Fauna

History Aboriginal prehistory European settlement

Ownership and Control Landholders Other Controlling Interests

Conflicts and Recommendations Wolgan Wildlife Refuge National Trust Landscape Listing The Original Wolgan Homestead Newnes Hotel Tourism and Recreation Industrial Site and Rai lway Village of Newnes Mining Agriculture Glow-worm tunnel National Parks and Related Issues

Summary of Recommendations

ORGANISATIONS AND INDIVIDUALS CONSULTED

MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

REFERENCES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Page No.

1. I. 2.

3. 4. 4. 6. 8.

10.

IJ. 14.

17. 18.

21. 21. 22 . 22. 23. 28. 33. 34. 38. 39. 43.

50.

52.

53.

54.

55.

-

AERIAL VIEW OF THE WOLGAN VALLEY Reproduction by permission of the Department of Lands, New South Wales

I I I

I I I I

-

rJ

/ I

H~~glMJJj~~~~ MAP 1 - LOCATION MAP SHOWING EXTENT OF THE WOLGAN VALLEY Base map is section of Bathurst Project Map reproduced by courtesy of Forestry Commission of New South Wales. '-..,

rv11'.iitt1~'~,ITHGc;ifN' -r '

-

.... '\.

CHAPTER 1

BACKGROUND

1.1 SCOPE OF THE STUDY

The area encompassed by this study is the Wolgan Valley and the environs with which it is interdependent. The boundary of the valley is distinct . At one end it is the catchment of the Wolgan River, on both sides it is the rugged sandstone escarpment and at t~e other end it is the junction of the Wolgan and Capertee Rivers. The interdependent environs are not so'.--easily defined and are a matter of judgment. The extent to which they are discussed in this report reflects the judgment of their importance. For example, the Colo-Hunter wilderness is only briefly discussed because it is a separate conservation proposal and it should be managed as a wilderness hinterland. On the other .. hand, the proposal to establish a colI iery on the plateau above the valley will have a direct and immediate impact.

The depth of the study was a function of the available funds and time , hence a detailed survey of the physical environment was not possible. A reasonably thorough survey of fauna and flora alone would exceed the value of the grant. Thus the depth of the study was a matter of allocating time and effort to the most important aspects for planning. The avai labi lity of voluntary assistance was also a determinant. In this regard, the response was wonderful. This report could not have been completed without the help of a number of people.

1.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE WOLGAN VALLEY

The Wolgan Valley 1 ies on the western edge of the Blue Mountains and is within the Hawkesbury River catchment. The local government area is the Municipality of the City of Greater Lithgow. The valley is mainly in the County of' Cook and is covered by the Parishes of Cox, Gindantherie, Barton, Wolgan, Cook and Goolooinboin. A small area is in the County of Hunter, Parish of Capertee. The valley is within a 160 km radius of Sydney. The distance by road from Sydney to Newnes is 191 km. The only road access is via Lidsdale, on the Mudgee Road 13 km from Lithgow. Newnes is a further 32 km from Lidsdale.

The Wolgan Valley is approximately 45 km long, measured from Wolgan Gap to the junction of the Wolgan and Capertee Rivers. Newnes is approxim-ately 20 km from Wolgan Gap. The width of the valley varies from 6-7 km at its widest point to less than 1 km in the gorge east of Newnes. At Newnes it turns sharply east into the rugged gorges of the upper Colo River.

The Wolgan River rises in two branches - t~e East and West Wolgan Rivers. The headwaters of both branchos are in the Newnes State Forest and contain spectacular gorges and canyons. The Wolgan River catchment, measured from 4 km above Newnes, is 238 $q.km (Water Resources Commission 1977 pers. comm.) The Wolgan River is an upland tributar'y,of the Hawkesbury River which flows out to sea at Broken Bay north of Sydney.

I.

II I. I

!I 'I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

~I d

-

I I I I I ,I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

The Wolgan Valley is known asa Ibottle neck out to a ~oad valley floor only to close in cut a gorge out through the sandstone cap. rugged escarpment only broken where dra1nage the plateau.

valleyl because it widens again where the river has The valley is bounded by a channels have entered from

Within the valley, close to the junction of the east and west branches of the Wolgan River, are two prominent landmarks - Mount Wolgan at 877 m and Donkey Mountain at 995 m. The valley floor is 600 m above sea level.

The village of Newnes, which is now no more than the Newnes Hotel .arid two private residences, is situated at the north-eastern end of the valley. Adjacent to the village site, along both sides of the river is the shale mining industrial site. From here it is a further 25 km to the junction of the Wolgan River and the Capertee River.

* * *

2.

-

To Lidsdale via the Gap, circa 1920.

I I I

-. ,_., ·1

I I I I

I - I

I I I I

-

"-:1 l .:.1

~I

~I

11 ~I

'I fl I1 fl 11

fl tl I

CHAPTER 2

THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

2. I GEOLOGY

The Wolgan Valley is situated at th~ north-western edge of the Blue Mountains Plateau and is within the Sydney Basin geological region. The area is also in the Western Coal District of N.S.W.

Strat i graphy • "' I • .... ....

The rocks of the plateau and cliffs belong to the sandstone dominated Narrabeen Group laid down during the several marine incursions of the Triassic period. Below this group lie the Illawarra Coal Measures, formed under extensive swamps produced by the retreating s~as which had laid down the silts.and fi"ne sands of the Lower Permian sediments. cThese. sediments bedon"g to"'the Shoalhaven Group which underlie the coal measures. The swamps were destroyed ~t the close of the Permian by orogenic move-ments and perhaps a coincfdent change of climate.

In the broader part of the valley floor, between Wolgan Gap and Donkey Mountain, outcrops of Devonian conglomerate, limestones, quartzite and siltstone occur. North-east of these, occqrs an outcrop of a small inlier of the granitic rocks of the Carboniferous Kanimbla Batholith which intrudes the older Devonian Silur~an sediments. Still further to the north-east, the valley floor bears a deposit of Quarternary alluvium composed of gravel, sand, silt and clay.

The Triassic strata. The cliffs forming the valley wall are composed of two of the formations included in the Narrabeen Group. The upper portion is Grose Sandstone composed of massive labile or sub-labile sandstone with beds of shale and siltstone present."· These rocks over-lie the softer sub-labile sandstone, silty.mudstone and shale of the Caley Formation. The differential weathering of these softer beds undermines sections of the Grose Sandstone resulting in the periodic breaking away' of blocks of the sandstone. Many of these blocks can be found at the cliff bases or further down the slope to the valley floor.

The Permian strata. The I llawarra Coal Measures lie immediately below the Caley Formation. The upper. bed is the Katoomba Seam - on'e of-the two major economic coal seams of 'the Illawarra Coal Measures in the Western Coal District. Below this seam, interbedded with sediments . i.ncluding oil shale, several other coal seams occur. In descending. order they are: the Middle River or "Di"rty Seam", fhe Irondale (Wolgan) Seam, the Lidsdale (Capertee) Seam and the Lithgow Seam. The Lithgow Seam is the second of the two major economic seams and it overlies the Marrangaroo conglomerate above the Shoalhaven Group sediments. In the Newnes area a bed of oil shale outcrops in the sandstone above the Irondale Seam. .

Below the coal measures lies the conglomerate of the Berry Formation of the Shoalhaven Group. This formation contains subordinate br.eccias and grits, sandstone, siltstone and shale. The Shoalhaven Group unconformably overlies Devoni~n and SJlurian sedt~ents. The-~ermian and Triassic strata lie conformably and horizontally one over the other, the entire formation dipping gently to the north and east.

3.

-

Economic Geology

The history of the valley is dominated by the exploitation of oil shale but it now appears that the only substantial'economic enterprise is coal mining.

Coal is the primary commercial geological resource of the valley. The Katoomba Seam contains good quality; low ash, steaming grade coal with a general working thickness of from 1 to 4 metres. The Middle River Seam has a high ash content and contains bands of dirt. The Irondale Seam contains high quality coking coal but the ash content is also high. The seam is about 2m thick at Newnes but this is probably its maximum,~ ....... thickness. The Lidsdale and Lithgow Seams also contain good quality coals, the best known outcrops of these occurring in the Capertee Valley and at Lithgow respectively. Neither seam outcrops at Newnes. Reserves of oil shale have been almost exhausted in the valley and recovery of the remainder is considered uneconomic. The Grose Sandstone is suitable for building and 'ornamental ·sturie.- . Other resources include aggregate, clay, shale and felspar:

2.2 GEOMORPHOLOGY

The Wolgan Valley was formed, and continues to be formed, by stream incision and transport of erosion products as well as active slope retreat at the valley walls. Slope retreat is caused by the weakening and removal of the Caley cl~ystone formations w~ich underly the Narrabeen sandstones. This sandstone cap then breaks off having been dissected into joint blocks by movements of the earth's crust and also by water moving through permeable sites. The water- emerges as springs below the sandstone and hastens the decay and removal of the Caley claystone. The entire process often culminates in massive landslides which greatly hastens slope retreat.

The base of the cl iff line coincides with the Triassic-Permian boundary and from.h~re there is a continuous debris slope to the valley floor and river. These processes have produced a landform with the following characteri sti cs:

the sheer sandstone valley walls with their testimony the on-going weathering processes

the steep·slopes from the base of the cl iffline composed mainly of weatheri_ng p_rocl:l!E~s of the Permian formations

the presence.of large sandstone blocks over much of the slope profile, and

the less striking features such as the sand/gravel bed-load of the river and sandy clay valley soils.

2.3 SOILS

The following information on the soils of the Wolgan Valley was derived from Hamilton's (1976) report on the 'Soil resources of the Hawkesbury River catchment, New South Wale~'. Hamilton states'that the soi+s are described in accord with Northcote's (1971) cla~sification and that the soils are delineated by visual appearance and inferred chemical and physical properties. To achieve this delineation, factors not consider-ed or not given prominence by Northcote were included. These include texture of the A horizon, the presence of rock or ironstone gravel and colour of the profile.

4.

I I I I I I

.1 I I I I I I I I I I I I.

-

I I I ,I

I.,. I I I 11

I I I I-I I I I I 't-,

TABLE

PROPERTIES OF THE SOILS OF THE WOLGAN VALLEY

Map Unit

Hydrological

Mechanical

Fertility

. .. Solarityand/or sodicity

E rod i b i 1 i ty

Valley floor & slopes

16 hardsetting sandy loam yellow texture contrast soi Is

Rapidly to moderately permeable IAI horizon overlying a very slowly permeable IBI horizon. Available water storage is small to very small.

Modera te 1 y compa'c ted I A I' horizon with tendancy to hardsetting or drying to a dense compact ion. The IBI horizon is densely to very densely compacted. Aeration is firm to good In the IAI horiz6n and poor to very poo~ in the IBI horizon.

Acid soils, pH5.5-6.0 chemically inferti le. Deficient in N, P, Ca and Mo.

Sodic to strongly sodic soil secondary saliniz-ation ~ommon but local-ised.

lA I - high IBI - very high

Extract from HaQilton (1976)

Sandstone plateau

2 grey and yellow~brown uniform soi Is

Uniformly rapidly permeable and excessi~~ly well drained soi I ... ~--Available water storage is very small.

Loosely compacted sand_ Aeration is excellent. Rock and/or ironstone .. gravel commonly occ~rs ~~ beneath the IAI 2 horizon.

Very acid soils, pH5.0-5.5 chemically very infertile severe defic-iencies of N, P, Ca and possibly Mo. Soil depends on organic matter for retention of nutrients .

Moderate

Note: Hamilton states that this data is of a general nature only.

!. ,

5.

-

I

In the 1:250,000 soil map discussed by Hamilton (1976) the soils of the Wolgan Valley are classed as hardsetting sandy loam yellow texture contrast sons (see Table 1). These occur· on Permian sandstone, shale and conglomer-ate deposits. Areas of·this unit are found in the steep-sided relative-ly flat valleys adjacent to the sandstone plateau at the south of Glen Alice and east of Mt. Victoria, and in a strip along the western side of the sandstone plateau extending from Lithgow to close to Sutton Forest. The landscape of the unit varies from flat valley basins, through undul-ating to hilly valley floors, to dissected plateaux.

The soils on the sandstone plateau above the valley are classed as grey and yellow-brown uniform sands. These 'occur on the Triassic sand~~?~e plateau which surrounds Sydney and in particular on the areas of strong relief on the plateau. These areas extend across the north of the catchment from Glen Alice to Gosford and south to the Warragamba Dam. The depth and character of the soils can vary greatly in short distances, depending on the landscape.'

2.4 CLIMATE

The Wolgan Valley lies in Region 10, Mitchell, N.S.W. as delineated by ~ the Bureau of Meteorology. The following notes are derived from the Bureau's survey of the Region (Bureau of Meteorology 1967).

Ra infall

The period of greatest rainfall occurs in summer and winter. The spring and autumn averages do not generally· exceed the summer or winter months. The rainfall is regarded as reliable measured by Australian standards. In nearly all months there is greater than 40 percent chance of one inch or more of rainfall. However, the winter and spring months have.a higher rel iabil ity than other months.

Temperature

Temperature varies greatly according to local variations in topography. o As a rule; .daily maximum temperature decreases by 2.7 e per thousand feet in summer and about 20C per thousand feet in winter. Daily minimum temperatures are more. affected by site and local air flow and the relationship with height is not so clear. However, a decrease of approximately I.Soe in summer and 10C in winter is a guide. These variations in site have strong implications for the Wolgan Valley with its extreme variations in altitude in close proximity making factors such as cold air drainage highly influential. On winter nights during anti-cyclol"")es cold-cj-ir ·Hows from the high peaks into hollows, collect-ing behind barriers to its free movement.

Topography over-rides other variables such as latitudinal and longitud-inal position throughout Mitchell Region. However, the south-east portion, which includes the Wolgan Valley, is influenced more by the sea and consequently its maxima and minima are more equable than the drier west and north. At Lithgowo only on one summer day in ten has the summer .temperature exceeded 32 C. In winter, it is unusual for temperature to rise above lSoe in July, the coldest month .

Frosts . . o

Temperatures of below 0 e are associated with severe frosts and light frosts are related to those between 20e and OOC. Since there is great

6.

I

I I I I I I I I

I I I

-

----- ., .• • ~ .- • • .-..... ---..• ~~:.~. ~. .... ... .. .. ,. .... . -. Iii1 .", ___ '. '_, ~ TAB.LE 2 CLIMATIC DATE NEWNES AFFOR.ESTATION CAMP

Source: Bureau of Meteorology

Station Name NEWNES PRISON CAMP New South Wale~ Number 063062, Latitude 33 deg. 21 mi n S . Long i tude 150 Deg, 15 Min E Elevation 1033.3 M

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug . Sep Oct Nov Dec Year 9 am Mean Temperatures (C) and Mean Relative Hum.idfty (%)

Dry. Bulb 17.7 17,3 15.6 13. 1 8.7 5.8 5.4 6.7 9.8 12.6 14.4 16.9 12.0 Wet Bulb 14.1 14.8 13.1 10.6 7.3 4.9 4.3 4.8 7.5 9.7 .11.3 13.0 9.6 Dew Point 11 13 11 8 6 4 3 2 5 7 9 10 7 Humidity 67 76 75 73 82 87 84 74 72 68 68 63 74 3 pm Mean Temperatures, (C) and Mean Relative Humidity (%)

Dry Bulb 21.5 19 .. 5 19.1 16.1 11.6 8.8 ~.6 9.5 . 12.7 15.4 17 .0 20.7 15.0 Wet Bulb 16.0 16.8 15.0 12.5 lQ,2 6,5 6.3 6,8 10.2 10.9 13.3 15.0 11.6 Dew Point 12 15, 12 9 9 4 4 4 8 7 10 JJ 9 Humidity 55 76:' 65 ' 66 84 71 71 67 73 56 65 53 67 Daily Maximum Temperature (C) Mean 23·3 22.7 20.9 18.0 13.5 10.6 10.0 11. 1 .~ .13.8 18.0 19.7 22.5 . 17.0 86 percentile 29.3 28!9 25.0 22.2 17.3 13.9 12.5 14.4 18.9 23.3 24.6 28.3 14 percen t i 1 e 16.9 17.2 '16. 1 13.6 9.7 7.3 7,2 7.8 9,4 12.4 14.4 16.3

Dai 1y, Minimum Temperature (C) 9.8 Mean.. 10.4 11.2 5.7 3. 1 .1 -1.1 .5 2.0 7.6 8.7 11.9 5.8 86. percent) 1. e 14.0 13.9 12.5 9.4 7.4 3.7 3.3 4.3- 6. 1 14.0 16, 1 17.4 14 percentile 6.6 7.8 6.7 2.2 -2.2 -3:8 -5.6 -3.9 -1.9 1.7 3.8 6.1

, Ra i nfa 11 (mm)

Mean 122 120 88 74 73 '93 64 81 66 91 87 93 1052 Median 136 96 76 63 59 62 49 77 61 84 74 66 1,097 Raindays (No)' Mean 17 19. 13 7 9 11 11 14 9 13 17 15 155

I,~:

7.

-

, ;

topographic variability in the Wolgan Valley and environs it is impossible to state the incidence .of frost.· However, reference to the·Newnes Afforestation Camp climatic data sheet shows that such temperatures are likely to be frequent.

Sunshine

The Wolgan Valley portion of Mitchell Region receives 9 hours of sunshine per day from November.to January. This daily amount decreases approx-imately one hour per month until June, when the average is 5 to 5~ hours of sunshine per day. On an annual basis, the average daily sunshine is 7.4 hou rs .

Cloud

The nearest station r.ecording cloud cover is at Katoomba, approximately 52 km direct from Newnes.

Average- amount (If C l:.otld "a'( Ra toorTlo'a', 9 a.m. ..

and 3 . nieas~ured· in 8ths p.m. of sky.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov:, ~Dec.

9 a.m. 5.2 4.5 4.8 4.2 3.8 3.7 3.7 4.0 3.5 4.4 4.4

3 p.m. 5.8 5.2 5.2 4.6 3.4 4.2 4.5 4.7 4.5 5.2 5.4

(Bureau of Meteorology 1967, p.63)

Cl imatic data: Newnes Afforestation Camp

Table 2 shows climatic data for Newnes Afforestation Camp. It has an elevation of 1033.3 m and is situated on the elevated tableland above the Wolgan Valley. Therefore these data will vary from those in the valley. However, it is the closest recording station to the valley and is indic-ative of climate. Furthermore, adjustments as described in the above text can be made for topographic variation between Newnes Afforestation Camp and the valley.

2.5 VEGETATION

The valley floor

4.6

5.6

The valley floor.is the area most affected by land clearing for ~gricu~ture. The natJve Kangaroo Grass (Themeda austral is) is the dominant herb but other introduced sown pasture species are present. Parts of the cleared 1 and are now ·subject- to heavy regrowth by- acaci a spec i es 'wh i"ch' ~lfe": obVious-ly an early state of succession back to eucalypt dominant forest.

The camping area at Newnes is in the valley floor environment and whilst it has been logged in the past and grazed at present, it still contains the dominant tree species. These are: Yellow Box (Eucalpytus melliodora , Forest Red Gtlm (Eucalyptus terreticornj~), .Ribbon Gum

Eucalyptus viminali~) and Acacia decurren~. Acacia falciformes is common on locations which have been disturbed in thi past as in the nearby industrial site.

The banks of the Wolgan River are characterised by Casuarina cunni~ghammi with Eucalyptus viminatis on the deeper uncleared sandy soils. Also present along the river is Eucalyptus cypellocarp~, however this species is mainly confined to the upper slopes and plateau. Eucalyptu~ bosistoana occurs in parts of the valley and these specimens are found

8.

I I I I I I I I I I I I I '1. I I I I I I

-

I I I I I' I' a

I I I I I I I I

some distance from the main p.0pulations in the Grose Valley, ,Liverpool area, Illawarra and.Burragorang Valley.

The 1961 Sydney 1:250,000 geological map (Department of Mines) shows a basalt outcrop approximately five kilometres below Newnes. The outcrop is not shown on the 1966 geological 'map of the same area. However, Mr. J. Pickard of the Herbarium (pers.comm.) believes that the outcrop does exist and that its vegetation Is significantly different from the surrounding environment and is worthy of further investigation.

The slopes "

The slopes have been less altered by man in recent years but they wer~'~ost likely heavily logged for mine props in the past. Scribbly Gum . (Eucalyptus rossii) occurs on the drier exposed west facing slopes whilst ~ucalyptus punctata is found on the deeper soils of alluvial fans and watercourses. Black cypress. (Callitris edlicheri) and Angophora flori-bundg are also C01l1mon. . Scattered 'specimens of Eucalpytus cypellocarpa . ::::-are found on' the slopes but it is mainly a plateau species.

It is likely that the vegetation on south-east facing slopes differs in~ significant ways from those facing north-west. This is because the latter are more exposed to wind and sun. However, the only difference observed in this preliminary account is that the vegetation on north-western slopes is shorter and sparser than that on the opposite slopes whilst dominant species composition remains similar.

The plateau

The plateau environment is generally described as Blue Mountains sandstone complex. It is rich in its diversity of vegetation types and species. Characteristic types are mal lee-form, swamps and rainforest elements in wet, protected gullies. Dominant eucalyptus species are Bl9xlandls Stringybark (Eucalyptus blaxlandii), Blue-leaved Stringybark (Eucalyptus agglomerata), Broad~leaf Peppermint (Eucalyptus radia~9)' Brown Barrel (Eucalyptus fastiga~a), White Ash (~ucalyptus oreade~), Sydney Peppermint (EucalyptU~ piperata) , Mountain Gum ( Eucalyptus dalrymplean~). The rainforest species found in the wetter gullies include those described oelow.

Rainforest elements

Some rainforest species are found in the upper reaches of the Wolgan River catchment, particularly the East Wolgan,and in isolated gullies such as that near'· the glow-worm.tunnel .a.t the head of Tunnel Creek. The only area visited was Tunnel Creek and nearby Bell IS Grotto. The main rainforest species found here are Blueberry Ash (Elaecarpus reticulatg) Native Frangipanny (Hymenosporum flavum), Possumwood (Quintinia sp), Coachwood (Ceratopetalum apetalum) and Black Sassafras (Atherosperm~ moschatum). These species are interspersed with numerous tree-ferns.

Noxious Weeds

There are numerous large infestations of Blackberry (Rubus fruticosis L . .ill19J throughout the valley. They are dispersed mainly over the v'alley floor where the forest has been cleared or disturbecj ,a'nd parts of the'

. , . industrial site.

9.

-

2.6 FAUNA

A fauna survey was outside the scope of this report. The valley and environs contain significant wildlife habitat and it is likely that the full range of indigenous species would be found by systematic survey. It has b~en estimated that there ari approximately 400 species of terrest-rial vertebrates in the Hawkesbury River Valley. This number consists of 250 birds, 50 mammals, 50+ reptiles and 50+ amp'nI5i~ns (Hawkesbury Valley Environmental Study Background Report 1973). It is expected that a large proportion of these occur in and around the Wolgan Valley.

The following birds were observed during field trips for this report .. ·.l't must be stressed, however, that the primary purpose of these trips was' to study land-use in general and not a survey of the av.ifauna. The follow-ing 1 ist is then only a superficial insight into the bird population of

I I I I I

the valley.

, •.. :;:·=-".d •. Spotte1J-'"Qti~((''ri1rush=""rCinclosoma punctatum) Eastern Whipbird (Psophodes olivaceu~) Wonga Pigeon (Leucosa rc i a me 1 ano 1 eucs)' Gang-gang (Callocephalon fimbriaturo) Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (~acotua galerita) Crimson Rosella (Platycercus elegan~) Eastern Rosel1a (Platycercus eximiu?-)

"'-.:,":=.'--:: ~-:' _. --== "" I

King Parrot (Alisterus scapularis) . Wedge-tailed Eagle (Aguila audax) . Brush Cuckoo (Cacomantis variolosus) Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo giga~) Superb Lyrebird (Menura superba) Black-faced Cukoo-shrike (Coracina novaehollandiae) Striated Tho~nbill (Acanthiza lineata) ~carlet Robin (Petroica multicolor) -Willie Wagtail (Phipidura leucophry~) Golden Whistler (Pachycephala pectoral i·s) White-throated Tree-creeper (Climacteris leucophaea) .~ellow-tufted Honeyeater (Meliphaga melanops) Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala) .' Red-browed Finch (Aegintha temporali~) Black-backed Magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen) Pied Currawong (Strepera graculin~) Little Raven (Corvus mellori) Grey Fantail (Phipidura ful(gnosa)

10,

I I I I I I I I I .1 I I I I

-

, , • =1 l'

•• • IJ

•

~I

~I

~I

11 11

CHAPTER 3

H I STORY

3.1 ABORIGINAL PREHISTORY

Mr. lan Johnson, School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, kindly prepared the following notes on Aboriginal prehistory.

According to ethnographic records, the Wo1gan Valley lay close to the boundary of the Wiradjuri tribe to the west and the Daruk tribe to the east. In view of its topographic situation, with access over fairii! easy country to the west but restricted access to the east via the narrow gorges of the Co10 River, it is probable that its ties are with the west rather than the east . . Both in this respect, and in terms of the environ-ment, relief, range of rockshe1ters and stone for tool-making, the' Wo1gan Valley is closely comparable ~ith the neighbouring Capertee. V~lley. Aboriginal occupation of both valleys is attested by chipped stone flakes and tools found. on the surface in almost all rockshe1ters of any size·, . particularly those near intermittent watercourses, swamps .or the mai~~ river.

To date no excavations have taken place in the Wo1gan Valley, and my.own fieldwork is limited to a few days archaeological site survey. However, the Caper tee Valley was the scene of an' important series of excavations in 1958-61, and, in view of the similarity between.the two valleys, a general statement may be made on th~ potential of the Wo1gan, based on my limited observations coupled with the results of theCapertee excavations.

The sites in the 'Capertee Valley are among the oldest and richest sites excavated in South East Australia, dating back to 11,000 years or more ago. Unfortunately these sites were excavated with very limited means and using methods which became outdated soon afterwards, and as a result the collections made are less useful than those excavated more recently. In particular, they cannot answer certain questions that have come to the fore in' recent years.

A large'proportion of each major site was excavated, so there is little possibility of satisfactory re-excavation. These sites remain of considerable importance, however, both for their early dates and richness and because it was on the basis of these that F.D. McCarthy proposed two phases of Aboriginal prehistory in South East Australia (F.D. McCarthy, 1964 The Archaeology ?f the Capertee Valley, New South Wales. Rec. Aust. Museum. V26·; 197-246). - flis 'division, though at present under review, seems to be the expression of an Australia-wide change in stone tools at about 6000 years ago, marked by the appearance of a number of smaller and more finely worked implement types.

The importance of the Wo1gan Valley may take one of two for.ms. We observe that in the recent past, the Wolgan and Capertee Valleys seem to have witnessed similar levels of Aboriginal occupation under similar environ-mental and topographic conditions.

1. If this similarity stretches back into t~~ past, the Wo1gan offers the potential of locating sites of similar richness and antiquity to those of the Capertee, documenting the appearance of the more refined stone tools of the past 6000 years. Equally, the apparently undisturbed nature of the sites I 'have "seen, holds out hope that a detailed study of the adaptation of the Aboriginal people to the resources

11.

-

provided by the valley, might eventually be possible.if those sites are not disturbed.

2. On the other hand, it may be that in the past, the lesser accessibility of the Wolgan .Valley resulted in more spasmodic occupation. If this were the case, a compar-ison of the two valleys could help document the process of expansion of the Aboriginal population into more remote areas as a result of population pressures, increasing mobility or increasing efficiency of the Aboriginal tool ki t. A particular case. of this might be the pressure caused by white settlement of adjoining areas.

Site recording

I

I

.' '.:" ..

I ~=~_~=.:-~:~!:'~:~r~;~~~:~~og~_~a~~=~~~onnaissance has been carrie~_:u~_i~ 0 th=e==~'_';::'_~' __ ;""~-'il~_l

.; ,

1. The western side of the valley from just south of the Wolgan River/Rocky Creek junction (GR 510230), northwest for approximately 2~ kms.

2. The western side of the valley from Newnes south to the road junction at GR 398198.

(Grid references on Ben Bullen or Mount Morgan 1:25,000 topographic maps.)

The reconnaissance was restricted primarily to a search for rock-shelters, owing to their visibility and my aim to locate s~tes with some d~ptg of archaeological deposits (Rockshelters act as a concentrating influence). As in the Capertee Valley, the sites are' mostly overhangs formed by large boulders resting on the talus slope which forms the sides of the valley. They. ar€! most often located on flats or terraces. The cliffs in the area do not seem to form extensive rockshelters at their bases, though these ma~ £orm from time to time to be later buried by the accumulating talus. There is, however, such a rockshelter approximately 1 km south of the Wolgan Gap, and this site has Aboriginal hand-stencils on the. walls and some depth of archaeological deposits.. It is probable that there are similar sites on the plateau region and around the base of the cliffs surrounding the Wolgan Valley, and others have been reported from n~ighbouring areas.

In all', 12 sites with chipped stone remains on the surface were located', toge~her wi~h a similar number of promising rockshelters (i.e. ones which appear to have some depth of deposits but where no Aboriginal relics were .found on the surface).

In view of the small area examined and the number of sites found, the Wolgan Valley clearly has considerable archaeological potential. The preceding discussion will have made it clear that this potential is primarily a scientific one, extrapOlated from results in the neighbouring Capertee Valley. Though no rock art has so far been found within. the Wolgan itself, there are a number of art sites, on the surrounding'plateau regions including the one at Wolgan Gap, and the excavated site~.in the Caper tee Valley also contain paintings. Equally, though I did not find any rockshelter sites as large as those excavated in the Capertee Valley, the potential for such ~ites exists. Positive protection of such sites is difficult - the best protection is generally remoteness. If any such sites with any depth of deposits, should be located, it will be clear from the preceding discussion that they are likely to be of considerable

12.

I I I I I I

--. '~'-I - .. ---.

I I I I I

I~

-

• J I

• • I

I I

I A I , 1I -I ~I

-I II 11 11'

archaeological importance, and every effort should be made to preserve them from the depredations of specimen collectors or excessive use by campers, animals etc. It has been suggested that informative education-al notices in archaeological sites help to protect them, but the best protection is probably the negative .one of not making them visible, commo~ knowledge or easily accessible .

The majority of the shelter sites I 'have found are at little risk from collectors, campers or other causes, owing to their small size. All that is needed for their conservation is an awareness that any protected area exceeding a couple of square metres and having a more or less level earthen or sandy floor, is a potential archaeological site, particula~ly if it is located near a source of water. It is the corpus of such ~ites rather than the in~ividual sites themselves which is of archaeological importance.

A third type of site which is very vulnerable to changi~g land use, are sites in the open. It 1.s known that the Aborigines lived primarily. in- _ . the open, construcing shelters from bark etc. Though many of these sites will have been washed away and/or buried by soil movements on the steep slopes of the area, some are still visible on the surface or exposed i~ eroded areas. Location of such sites, however, requires an intensive ground survey, and their conservarion would require consideration of the effect of changing land use on erosion and soil movement. Every effort should be made not to site paths or vehicle tracks on or near them, not only to avoid direct physical damage but also to avoid depredation by stone tool collectors. At the present time we do not have the ability to extract much information from these sites, but rapid advances are taking place elsewhere and these si tes vdll probably become increasingly important in the future. If in situ conservation is not practicable, many of these sites can be effectively safeguarded for future study by a controlled total collection made by a competent archaeologist.

In conclusion, the Wolgan Valley appears to present a considerable scientific archaeological potential. Any changes in land-use should be accompanJed by an archaeological reconnaissance of the area involved with a view t~ locating archaeological sites, determining the effect of such changes and suggesting effective conservation measures.

Mr. Johnson mentioned the Aboriginal site 1 km south of Wolgan Gap. Fol,lowing ,is a further description of this site derived from records of the Australian Museum and National Parks and Wildlife Service of N.S.W., The site is located at GR 316 090 Cullen Bullen 1:25,000 map sheet. It consists of a leaning rock face 50 m high and approximately 100 m long. Below the face is a large occupation deposit. Test trenches yielded points, scrapers and small cones to a depth of 45 cm. The most signif-icant features of the site are a large number of red and white human hand stencils and stencils of an axe and a boomerang. There is also an unusual small bark stencil of a human figure which could have been used

- in rituals. This figure is particularly interesting because an identical one is to be found (again in association with stencils) in a shelter near Bulga. The sitewas an ideal place for secret ceremonies both from its seclusion and general layout.

The site is readily accessible via a short track from Wolgan Gap and has now been defaced and is untidy with litter. The National Parks and Wildl ife Service of N.S.W. considers that the defaced and weathered

13·

-

Cricket match, 'The Flat' Newnes, circa 1920. The foundations of the school, centre rear, can still be seen above the campground adjacent to Little Capertee Creek.

I I

I I I I

-

I

I II II 1.1 1I

I I I I

stencils could be cleaned without damage. The previous Blaxland Shire Council did approach the Service for more regular patrols of the site but this has proved too difficult to maintain on a regular basis since the nearest ranger is stationed at Hartley. For regular patrol, inspection and maintenance, a ranger would need to be located closer to the site. Since this is unwarranted for the Aboriginal site alone, the ranger would require wider duties. This could well eventuate from an expansion of the Blue Mountains National Park as recommended elsewhere in this report, and the recent dedication of Patoney1s Crown Nature Reserve.

3.2 EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

The first recorded. European discovery of the Wolgan Valley was by Robert Hoddle who in 1823 unsuccessfully sought a route from Belli s Line of Road to the Hunter Valley. Hoddle was employed by the Surveyor-General, and had just completedthe __ init.ial surve~ of the Bell's line of Road •. Soon __ after its discovery James Walker of "Wallerawang" station establ ished the "Wolgan" out-station in the valley. (see Chapter 5.3 "Original Wolgan homestead" for current status.)

Small prospecting pits had been noted in the area as early as 1868 but Camp be I 1 Mitchel I is recognised as the first to open the Newnes shale seam in 1873. Mining started in 1903 but it was not until 1905 when the Commonwealth Oil Corporation Limited was floated in the United Kingdom that large-scale commercial mining commenced. This Company also had shale mining interests at Hartley Vale and Torbane. The town of Newnes was named after Sir George Newnes, one of the Directors of the Corporation and a well-known British publisher at the time.

The decision to mine and develop a town at Newnes rather than at Torbane was because Newnes was closer to the western railway line. The town was divided into "company" and "government" sections. Estimates of its population vary from 1,000 (McLeod Morgan 1959) to 3,000 (Luchetti 1976) people. The industrial works included coal and shale mining as well as a brick'works. Products included lubricating oils, paraffin, coke, sulphate of ammonia, kerosene, candles and naptha. Petrol was not regard-ed as an important product because the internal combustion engine had not become popular. The coke was of a high metallurgical quality and was transported to the smelters at Cobar.

Traosport'to and from Newnes was first via Lidsdale by a road constructed by the Public Works Department in 1897. Next came a "coach road" from Newnes Junction then known as Dargan's. The railway line from Newnes Junction to Newnes was commenced in April 1906 and comp1eted in November 1907. The siting, design and construction of the railway was a civil engineering feat of its time as well as " .... one of the most ambitious undertaken by private enterprise in the state if not in the whole of Australasia" (Eardley and Stephens 1974, p.125).

The Commonwealth Oil Corporation Ltd. mined in both the Capertee and Wolgan Valleys but Soon closed the Capertee operation and concentrated on Newnes. Located at Newnes was the shale retorting bench, brick kilns, power-house for generating electricity, coke works, oil refin~ry, storage tanks as wel I as the entire support and administrative infrastructure. However, Newnes was soon troubled with high costs, inappropriate retorting technol-ogy, industrial trouble and low prices for its products now facing compet-ition from the incandescent gas mantle and electric light. To accumulate

14,

-

Newnes railway station and stores, circa 1920.

- ------ --

'. 11 '11 II II I I I I I

I - I

I I I I

-

I I I I I I

capital the Corporation tried to sel I the railway to the State Government. However, the offer was refused. The time of the first closing of the works is given as 1911 by Lishmund (1974). However, according to Eardley and Stephens (1974 p.207) the works did not close until 1913. It was announced on February 16th, 1914 that David Fell was appointed as receiver to bring the operation to conclusion.

The beginning of the First World War provided the impetus to keep Newnes in operation and various economic and technological adjustments were made. John Fel I, a brother of David, came to Australia from England to regesign the Newnes retort bench. Then in April 1915 an arrangement was r~ached where John Fell and the Commonwealth Oil Corporation were associated under the name of John Fell and Company. John Fell moved equipment from Hartley Vale to Newnes and also railed Torbane shale to Newnes for treat-ment. His plan was to concentrate the manufacturing section of the district shale oil industry at Newnes.

Again the industry was affected by industrial and economic problems and in September 1919 the Commonwealth Oil Corporation was re-formed wit~~ John Fell being appointed manager at Newnes. However, this was also unsuccessful and the works closed between November 1919 and February 1920 according to Eardley and Stephens (1974 p.210) whilst Lishmund (1974 p.6S) states that the mines closed in 1922.

In 1921 an abortive attempt was made to retort the shale in situ by setting the seam alig~t. At this time people were still employed at Newnes as maintenance staff and also to refine some overseas crude oil. In 1924 Fel I built a refinery at Duck Creek, Clyde to produce motor fuel from Newnes shale. This was unviable and in March 1926 the maintenance staff on the Newnes railway and refinery were paid off (Eardley and Stephens 1974 p.211).

The closure was once again short-lived. In 1930 A.E. Broue formed a company including Broken Hill Mining interests. This association only lasted ·a· few months before Broue formed Oi 1 Producers Newnes L imi ted. Work started in 1931 on repairing the railway and plant but the men ceased work as soon as they realised there were no wages forthcoming. So once again Newnes closed only to be re-opened by the newly formed Shale Oil Development Committee Limited,to which the Federal Government granted 30,000 pounds to employ miners. By November 1931, 3,000 gallons of crude oil per day was being retorted at Newnes but even so,production ceased in March 1932.

On April 2, 1932 the Federal Government called tenders for companies to operate Newnes but later in the month closed the works. In 1932 a Melbourne company was approved but it failed to raise sufficient capital. In 1933 the New South Wales and Federal Governments financed a committee to investigate commercial oil production at Newnes. The committee reported that Newnes was still ~iable as a site for producing motor and fuel oils. Various companies were unsuccessfully approached to operate the works so in May 1936 the Federal Government announced it would nationalise Newnes.

.. In April 1937, Mr. George Davis and the New South Wales and Federal Governments joined to form National Oil Proprietary Limited to mine the Wolgan-Glen Davis shale depOsits from the Glen Davis side. A new works was built at Glen Davis utilising most of the Newnes equipment which was railed to the new site. This was the first demolition activity at

15.

-

The home of Mr. John Fell at Newnes, circa 1920.

I I I I I I I I I

I I I I I

I I

-

!. I. I I I I I I I I I I I

Newnes and heralded its. decay to its present condition. The Newnes Railway was abandoned and a pipeline laid along its path. Operations at Glen Davis started early in 1940 but the company was unable to mine sufficient shale of the correct quality to employ the retorts. Further interest in shale mining emanated from the Oil Shale Mission of the United States Board of Economic Warfare visit to Australia in 1942. The Mission . recommended large expansion.of the Glen Davis works using new Renco retorts. A pilot retort was established but economic production was still elusive and the plant was closed in May )952 ..

The serviceable equipment at Newnes was moved to Glen Davis around 1·9~O but the .wholesale dismantling of what remained at Newnes took place gradually. Eardsley ·and Stephens (1974 p.2J7) state that the railway lines were used in North Africa during the Second World War. Abandoned locomotives and other useful metal were cu~ up for scrap during the 1950s. Bricks and other ~uilding ~~ter-ial~were ~lso removed so tha~ today only ~ a small proportion remains of this once optimistic enterprise. Newnes Hotel, which has been operating continuously, is the only building that remains intact; . ~~

* * *

, .

16.

-

41

11

•• I-

I I

I

I f

CHAPTER 4

OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL

4.1 LANDHOLDERS

Forestry Commission

.. -~'--~-'~''f

. , I 1:-

I' The Forestry Commission has two forests in. the Wolgan Valley and enVirons:

.1 r

\ .. : ... -Newnes State Forest. The -Forestry Commission Bathurst Project Map shows Newnes State. Forest as an area of 13,000 ha. However, it was expanded by another 16,000 ha by notice in the Government Gazette of March 12, 197p. The forest contains Newnes Afforestation Camp which manages a Pinus radiata plalltation. Most. of the fore'sf j's-located on th~ pl~ieau-~round the ~eadwaters of the Wolgan Valley. This vegetation zone' is discussed in Chapter 2. The Fores'try Commission states th~t up to approximately half the area could be~ suitable for pinus radiata and that the remainder will be used for low quality timber production from native species, mainly White Ash (Eucalyptus oreades) for mine props. The rate of pine planting is approximately 100 ha per annum. It was stated that no pine. planting would occur in the visual catchment of the Wolgan Valley.

Wolgan State Forest. The Wolgan State Forest is situated in the Wolgan Valley and covers 1,454 ha. It contains forest extending from the valley floor, up the slopes, to the plateau thereby containing species not found in Newnes State Forest. Dominant species are those described in Chapter 2. Management of the forest is primarily for durable hardwoods, it being one of the few in the district which supplies this timber. Wolgan State Forest adjoinS_Ben Bullen State Forest, an area of 7,928 ha which extends north-west from the valley.

Agricultural holdings

A total of 8062 ha of land in the Wolgan Valley is used for grazin~. Beef cattle and sheep raIsIng are dominant forms of commercial agri~ulture. The land is held as freehold; Crown lease, permissive occupancy, annual lease and forestry lease. Land tenure is shown on map 2. There are only four properties based on freehold landCbut which also encomp~ss lea'ses} that are viable agricultural enterprises. Only one of the owners of these properties is a full-time farmer resident in the valley. Of' the remainder, one property is managed from outside the valley, the owner of another resides in Lithgow and the other owner has an 'off-farm occupa t ion.

In addition to the above properties, annual leases for grazing purposes are held by two different parties. These leases only provide small returns being located on very marginal lands, mostly bush.

National Parks & Wildlife Service of N.S.W. ! ' r

The National Parks & Wildlife' Service estate includes the 3,230 ha Pantoney1s Crown Nature Reserve. Although it is not in the Wolgan Valley it is adjacent to it on the north-western side and~is discussed in~ Chapter 5.l~ of this report as its management impinges on national park proposals in the area. The Blue Mountains National Park is separated from the valley by Newnes State Forest.

17.

t,

l 01. I I) 11 11 1I I1 I:

0-1

I· I I .1 I I

-

I

, OIItlll'mU)

I

I I

Jt

,f

\ ~ .~~ MIN/~rr;§W'P£ IU,rlOlIlS .1~

'.-, ...

fAIrJER1IElE

Land Tenure

Ilr.~ Freehold • leasehold

Vacant Crown land

State Forests ;j~ _i1-- • Pantoney's Crown -1.- . Nature Reserve

I Boundary of Blue Mountains . ~.- r -: ~Jational Park extensions

''! . i proposed-in Chapter 5.

MAP 2 - BASE MAP: SECTION OF COUNTY OF COOK Reproduced by permission of the Department of Lands, New South Wales.

I

J

J

I

I

-

4

~ • • • I

I

i -1

Village of Newnes

The ownership of village lots is discussed in Chapter 5.7. It is insig-nificant in terms of area of land but extremely important for planning.

Crown lands

The Crown owns extensive lands in the area and these are discussed in Chapter 5. I I in relation to national park proposals.

4.2 OTHER CONTROLLING INTERESTS

Besides ownership of land in the valley, there are other controlling interests. These are discussed below:

Department of Mines

The Department of Mines and its lessees have extensive interests in the area. This interest relates primarily to coal but also includes lesser mineral deposits such as the shale ash deposits at Newnes. Mining is fully discussed in Chapter 5.8.

N.S.W. Planning and Environment Commission

The Planning and Environment Commission has some control over the valley through its head of power to impose and oversee an interim development order (100) through local government. The relevent 100 for the Wolgan Valley is 100 No. I Shire of Blaxland March 7, 1975. Blaxland Council has since been amalgamated with Lithgow City Council to become the Council of the City of Greater Lithgow. The 100 has the Wolgan Valley zoned Non-urban la which restricts development to one dwelling per 40 ha. However, dwell ings are permitted on land less than 40 ha under clause 17 of the 100. The implications of this serious shortcoming are discussed in Chap.te r 5.7 liThe v i I I age of Newnes 1 •

On November 16, 1976 the Commission introduced a new zoning policy for land outside urban areas. This policy was developed to counteract the detrimental aspects arising from the lack of positive rural land-use zoning and planning in N.S.W. Within the new zoning system are ten Rural Environment Protection zones. They are:

Rural Environment Protection (Es~arpment) 11 11 11 (Archaeological Site) 11 11 11 (Historic Site) 11 11 11 (Scientific Site) 11 11 11 (Wildlife Refuge) 11 11 11 (Wetlands) 11 11 11 (Estuarine Wetlands) 11 11 11 ( Foreshore P rotec t ion) 11 11 11 (Scen i c) 11 11 11 (Water Catchment Area)

The Escarpment, Archeological Site, Wildl ife Refuge and Scenic~ones are relevent to the Wolgan Valley. If the recommendations of this report are enacted upon, the Commission's new zoning policy wil I be applied to the valley.

18.

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

-

I I I I I I I I I I I I,

I I I I

~~-~~-~~~~-~---------------------------------,

Council of the City of Greater Lithgow

The Council of the City of administration of the 100. Council's responsibilities

Column 1 Co 1 umn " Zone and Development colour or which may be ind i cat ion carried out on 100 Map wi thout the

consent of the Counci 1

1.Non-urban Agriculture: (a) Non-urban forestry; IIAII Li ght dwe 11 i ng-brown. houses ref.

to in Clause 1 3 (1) (a)

Greater Lithgow is responsible for day to day The following extract from the' I DO shows the

in the va 11 ey :

Col umn I I I

Development which may be carried out only wi th the consent of the Counci 1

Deve I opmen t other than referred to in Columns II , IV and V.

Column iV

Deve 1 opmen t wh i ch may, be carri ed out only with the concu rr.ence of the Commission

Industries other ,than extractive industries, offens ive or hazard-ous indust-ries and rural indus-tries.

Column V

De ve I opmen t whi ch may not be car'r'i~d out.

Motor show-rooms; res i den t i a 1 bu i 1 d i n~gs ; -shops other than general stores.

Source: Alteration of Interim Development Order N6. 1 Shire of Blaxland Government Gazette No. 42, 7th March, 1975.

It should be noted that it is Clause l3(l)(a) referred to in Column I I above that allows bui Idings on l.ess than 40 ha where such land was an existing parcel (see Chapter 5.7 liThe Village of Newnes"). .. The Electricity Commission

The Electricity Commission in a letter dated June 1, 1977, states: liThe investigations which the Commission is undertaking in the'Wallerawang region ar'e currently associated with resources assessments and it is therefore not practicable to define possible project locations. The most that can be stated at this stage is that if a power station is constructed in the future in,that region it would not be in the Wolgan Valley and its impact would,most likely be confined to some utilisation of the headwater area's of tributary streams and the' uti 1 isation of some of the water resources at the, downstream end of the valleyl'.

This reply is non-commital given the proliferation of rumours about the Electricity Commisslon's plans in the area. It seems certain that the Commission does plan to build a major new power station, probably located within the recently expanded Newnes'State Forest. Recent Government· announcem~nts indicate the generating plant will be Ilnked with a cOal mining p·roject. Having no details it is impossibl'e ·to state what the impact of this proposal will be o'n. the Wolgan Valley. However, it js to be hoped that any development would be subject to stringent environmental safeguards.

19.

-

"

I I , f I I ;1 J

11 ,I tl I I I I I I I I

Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board

The Board has no projects planned within the WoJgan Valley, However. it does have plans for damming the Colo River at some future date. The Wolgan Valley, being in the Colo catchment, would then come under Section 56A of the Board's Act. This Section allows the Governor to declare outer lands as catchment areas and thereby control certain types of development and use without actually owning the land as with inner catchment areas.

' .......

20.

-

Valley scene.

I I I I I Ic-

I I I I

I I I I I

-

11 .. 'I ,I 1I II 11

1

tl 1

I1 ! I !I

CHAPTER 5

CONFLICTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5. 1 WOLGAN WILDLIFE REFUGE

The entire Wolgan Valley was proclaimed a Wildlife Refuge under Section 22 of the Fauna Protection Act, 1948. Wildlife refuges are private, local government or government owned lands where the owner or managing authority enters into an agreement with the National Parks & Wildlife Service to protect fauna and flora and its habitat. .-Wildlife refuges are not areas dedicated under the National Parks and Wildlife Act. They are proclaimed by the Minister in the Government Gazette and can be revoked by either party to the agreement.

I n the past ,man~ 'landhol ders proc la imed the i r-propert i es . as:'wi ld I He .. -'-~::;::: refuges to prohibit shooting. There were two good reasons for this: first, the property owner was granted distinctive signs to ward off shooters; second, the penalty for shooting protected fauna was higher~, on wildlife refuges than elsewhere. This is probably why the Wolgan Wildlife Refuge was proclaimed - to deter weekend shooters. However, the original purpose of the wildlife refuge concept was to promote the integrated management of wildlife and agriculture. Thus habitat preser-vation and wi Idl ife management are seen as more important than only keep-ing out shooters.

To bring wi Idl ife management and habitat maintenance back into the wi ld-life refuge system, all refuges were automatically revoked by the National Parks & Wildlife Act, 1974. Under the new Act the penalty for illegally shooting protected fauna was made the same for all lands thus removing this incentive for wildlife refuge status. The sign denoting the Wolgan Valley as a wildlife refuge still exists but it was automatically revoked along with all other refuges.

Since 1974 the National Parks & Wi Idlife Service requires potential wildlife refuge owners to demonstrate that their land contains significant wildlife habitat and that it will be managed as an integral part of the whole property. This is the condition upon which the Wolgan Valley could be once again proclaimed a wildlife refuge. Since the co-operation of all the pr.operty owners i.n wildlife management is unlikely So then is the proclamation of the whole valley as a refuge. However, individual property owners can still apply to have their properties declared wild-, life refuges.

5.2 NATIONAL TRUST LANDSCAPE LISTING

The National Trust of Australia (N.S.W.) has a system of listing beautiful landscapes for which it advocates special scenic protection measures. This recognises that scenery is a resource worthy of protect-ion in its own right. Before a landscape can ge given a Classified listing it must be evaluated by the Landscape Conservation Committee and approved by the Trust Council. Public interest and representations are also taken into account. Those landscapes given,a -Classified Jjsting by the Trust are then submitted to the Australian Heritage Commission for inclusion on the Register of the National Estate.

21.

-

Newnes Hotel.

r\_!.-: __ ' \A,_I ___ u __ ,.., ... +,.,,"" ....

I I I I I I I I I I I I I -I I I I I I I

-

I ·1 I ~I

•

The Trust approved the Wolgan Valley .to be listed-as a CLASSIFIED LANDSCAPE on November 22, 1976 for three reasons: scenic quality, . recreation value and the Newnes industrial site. The boundary to the landscape is defined as the e~carpment ~hich surrounds the valley. The most appropriate method of ensuring.the National Trust's recommendations are followed is for the. valley to be.declared a scenic protection area. This is further discussed in 5.11.

5.3 THE ORIGINAL WOLGAN HOMESTEAD

The original Walker 'Wolga~' homestead (see Chapter 3.2) still stan·d's-. The homestead which .has National Trust Classified listing, is disused and in poor condition and stands on 'Wolgan Station ' owned by the Webb family. It is a large slab cottage of about six rooms. The year 1874 is etched into the stone chimney.. The front of the house is constructed _________ of.verticaJ sl.c;t~s but there i~

-

•

I I I I I I I I I

I I I

----------- - ---

Heritage Bill, discussed above in relation to the odgirial Wolgan home-stead, also applies to the hotel. However, eventual compulsory acquisition and a lease-back arrangement with app~opriate conditions should not be overlooked.

Another alternative would be to harness the potential for voluntary assistance and financial donations towards restoration. There is such strong positive feeling about the hotel and its place in the hfstory of Newnes that voluntary restoration and funding are by no means impossible. This would, however, require administration by a responsible organisation and long-term success is not assured.

It is extremely difficult to. discuss Newnes Hotel without mentioninQ Mr. J i m Ga'l e, a man. he Id in fond regard by most peop 1 e who enjoy th'e~'~ Wolgan Valley. W~i~st at the time of writing, Mr~ Gale had relinquished ownership of the hotel it is still to be hoped that any future management recognises his presence and contribution to this delightful hotel.

5.5 TOURISM AND RECREATION

The Wolgan Valley has a long association with tourism and recreation. As early as 1911, a rail trip from.Sydney to Newnes and a return trip by. coach to Wallerawang' thence rail to Sydney was a popular weekend out-ing (Eard1ey and Stephens 1974 p.94). Since then, the record of tourism and recreation is vague and no relevant.statistics exist. Given that personal motor vehicle transport has only become common in Australia since World War I I, it is likely that the valley has only recently become popular once again. But even" in this recent period the type of visitor has changed with changing public tastes and available transport technology. Prior to the recent wave of well-equipped motor-oriented visitors the valley was a focal point for people attracted to its isola~ion as much as anything else. Today, twenty to thirty cars, with an average of three passengers per vehicle, plus numerous motorcycles enter the valley each weeken~\. Most stay at least one night. On long weekends the number increases dramatically and over Easter 1977 there were upwards of 600 people camped around Newnes.

Recreation at Newnes is interes·ting in that it is environmentally and techno log i,ca 11 y defi ned. That is, the envi.ronlnent - phys i ca 1 and--cultural - attracts people whilst available technology provides tr:anspo.rt there and frequently defines on site activity. Unlike other areas with similar natural features, Newnes iscnot-1l1anagemene"defined.· For example, once an area is dedicated as a national park, historic. site ·or state· recreation area, then it is managed in a" particular way which defines use of the area. Thus management must be added to other facbors governing use. However, at Newnes there has been no official management policy and use has been largely self-regulatory and lassez faire.

In the circumstances it is highly likely that recreation at Newnes fluct-uates according to popular taste and is underscored by conflicting values. For example, it is probable that the seeker of quiet natural beau~y has been, or is being, replaced by someone whose perceptions can more easily accommodate the noise and impact of many trail biKes. The self-regulat-ory aspect also ensures that people who demand more than the available facilities do not stay or make a return visit.

23.

I I I I I I I, I

.. I I I I I I I I I I I I

-

I I I

I I I I I

Easter 1977. Looking down on the main camping area on both sides of the Wolgan River at the junction of the Little Capertee Creek. Note clustering of campers.

-

-I --• .. -.J I I I I I I I I· I 1

Camping

Virtually the entire valley floor, by virtue of its private ownership, is excluded from the public for recreation and camping. The only camping area is in the vicinity of Newnes. Camping is permitted on the 16.19 ha parcel of land in the village of Newnes (Portion 9, Parish of Gindantherie) owned by Mr. K.J. Gale and on the industrial site held as annual lease 57/13 by J.M. Gale, P.J. Donnelly and K.W. Hall. There is a symbiotic relation-ship between ownership of the hotel and camping. However, the above areas are also used for beef cattle grazing.

Campers distribute themselves according to personal taste and v~hicle. The main concentration is around the jun~tion of the Little Capertee C reek and the Wo'l gan Ri ve r . However, campers can be found among the industrial ruins to the end of four wheel drive access 13 km east of Newnes. Two wheel drive access is difficult beyond 3 km east of Newnes. Within this area, campers are able to choose a site almost anywhere they desire. Sites vary fro'm sedate caravans in the cleared land around' Little Capertee Creek to a bed of bracken in one of the beehive coke ovens. One of the advantages of a lassez faire camping area is that people can choose a spot according to their wants without being spatially and behaviourally confined by regulations .

The lac~ of regulations. means that the camping area is not in . perfect condition. There is erosion, and boggy and deeply rutted vehicle tracks. However, these conditions do not deter visitors and the damage to the environment may well be much less than would occur if the camping area were more sophisticated and thereby attracted many more people. This is one dilemma facing national park managers which has not occurred in the Wolgan Valley. Approximately 25% of the camping area around Little Capertee Creek is bare of ground cover. This is quantitative whilst the qualitative response has not been a deterrent. The current impact on the environment from camping is small compared to the first mining activities. Further, all the camping occurs on habitat that has been greatly altered through urban and industrial dev-elop~ent in the past and grazing more recently. This is not to argue for the status quo and is said simply as a word of caution.

Toilet facilities vary from a convenient location in the bush to improv-ised screens with pits or use of the hotel toilets. Presumably, those who require better facilities do not use the area. The effect of human wastes on,the environment is not known. Some people bring their own drinking water, others use water from the River. There were no compLaints about water nor are there any records of illness attributed to polluted water.

For an unregulated area, the campground is surprising. There is far less litter than in many regulated areas. Part of the price of regulat-ion may be that people assume there is someone paid to pick up litter, therefore 11 •••• why not throw something out - the a.ttendant wi 11 pick it up."

Cans, bottles and other refuse is heaped by campers and the hotel licensee. It is then dumped by the licensee in a large erosion gully at the rear of the camping area. This is all "a bit unsightly especially when there are numerous heaps sti lIon the camping area but the system works. There may be pollution by runoff from the dump but it is not obvious and further testing would be necessary to determine if that is the case. "

24.

I I I I I

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

-

I JI

I I

I I

I I

I . I

I I I - .. I

, , I I I

I I

I ~

I I

I Two different camping styles in the Wolgan Valley.

-

• • , I I I I I I I I I I I I r

The main factor regarding camping at Newnes is that it is virtually self-regulatory and those who enjoy,or tolerate~the lack of facilities use the area whilst those who do not, go elsewhere. Some, of course, bring their facilities with them, for example, the caravaners.

Characteristics of recreation

A valid recreation survey was beyond the scope of this report. The time scale did not allow a field trip for hypothesis development and pilot survey prior to winter and the absence of suitable holiday periods. The scope for a recreation survey at Newnes is enormous and a fascinating study could be made. Hypotheses and propositions for testing aboull'd:

the dynamics of self-regulation a comparison of environmentally d~fined recreation at Newnes

to management defined recreation on a simblar environment the same d is tance from Sydney. _ _ _

the wide range of activities at Newnes provides an opportunity for measuring the interaction between various activities and to overcome the major flaw of many recreation surveys - their tendency to compartmentalise activities and rank them on inval id cri teria. (see discussion below),

perception studies related to the admixture of trail bikes and natural environment.

socio-economic data and point of origin. One hypothesis is that visitors to Newnes come from a more heterogeneous socio-economic background than national park users who are often claimed to be mainly of middle-class affiliation (Wilkinson 1972, p.237-47).

This discussion of recreation in the Wolgan Valley is based on being a participant/observer in the valley over two Autumn weekends and the Easter 1977 holiday period. During that period the following activities were observed and recorded:

trai 1 bike riding bushwalking inspection of industrial site four-wheel drive treks sports (e.g. cricket) rockcl imbing

'sustenance activities (e.g. cooking, collecting wood) photography environmental education (e.g. scouts) gathering of friends and family drinking at Newnes Hotel pleasure driving children playing swimming fossicking painting

The authors of many recreation studies attempt to identify the obvious recreation activities and then assume that they are also the most popular. Furthermore, these activities are often listed iri~, questionna~ce and respondents asked which they favour most. There is usually an 'other' category but this is biased because, being last, and undefined, it appears to the respondent as an afterthought. Experience as an'observer in the Wolgan demonstrates how inaccurate and misleading such studies can be.

25.

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

-

I I I

I I I The coke ovens still have their uses - one for a kitchen and another for a bedroom.

I _I

-

I

I ~I

Some of the least obvious recreation activities can also be the ~ important, for example:

Gathering of friends. Viewed from above,over the Easter holiday period the main campground around Little Capertee Creek showed extreme cluste~ing of campers. This could be partly explained by the way that one campsite draws socially oriented people to its proximity wllich in turn attracts others. 'However, ground observations showed numerous family and activity groups as well as grouping of caravans and four wheel drives. One group had even fenced themselves off.

Sustenance activities. This is another of the less obvious actl~ities but an extremely important one. Camp establishment and maintenance and camp cooking were a large part of many visitors recreation experience. This is enhanced by the absence of regulations,-People can foster their idiosyncracies in camp layout. Collecting wood was greatly enjoyed by peopl~ dep~iv~d of this kind ?f actJvity , in their normal routine. There is room for different interpretations on the significance of these sustenance activities. For example, cooking while on holiday is regarded as a chore by some. However, the number of people observed collectingtwood, tending campfires, and~~ cooking in family groups indicates that it is also a very important recreation activity.

Drinking at the hotel. Not likely to be listed as a recreation activity,but of significance,is drinking at the Newnes Hotel. Whilst many visitors drop in for a casual drink, others go to the Wolgan Valley as a place to 'have a few beers.'

Off road recreation vehicles

The rough unsealed road into the valley, the old mining and industrial site roads, the unfenced areas around the camping ground and the general atmosphere of isolation are the ingredients of an ideal location for off-road recreation vehicles (O.R.R.V.) The only two of this type of vehicle observed in the Wolgan were trail bikes and four wheel drives. Depending on one1s point of view, thege vehicles are a wonderful tech-nological aid to extend man1s reach into, or over, the physical environ-ment or they are a noisy, polluting menace, dangerous to those gentle souls who prefer to walk the tracks. Regardless of the position one takes in this debate, O.R.R.V.'s do cause a significant and controversial impact on 'the Wolgan Valley. The uncontrolled use of trai 1 bikes and four wheel drives has caused tracks to be 'pushed' through the bush in and around the campsite resulting in significant erosion. Trail bikes are the greatest problem in this regard. Over a busy weekend or holiday'period the Newnes area of the Wolgan Valley is dominated by trail bikes. In a preliminary recreation survey of the Newnes camping area by McKay (1976), trail bikes were listed as the most offensive aspect of the area.

This may change as the new (early 1977) owner of the Newnes Hotel is attempting to prevent trail bikes using the camping ground and the industrial site. Since this area includes all the freely accessible areas to the bush tracks this prevention would g~eatly reduce use of trail bikes. Indeed, in April 1977, the first new signs proh"tbiting trail bike use were erected. How successful the programme will be remains to be seen. Since many of the trail bike riders are among family groups who provide custom to the hotel, there may be a compromise. It may also be physically impossible for one person to control trai I bikes over a large area and run the hotel at the same time.

26.

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

-

I I I I I ~I.,

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

Trail bike riders, four wheel drive and walkers at the Wolgan River.

I

I

I I

I I I I I I ! a u

u

il

-

• • • • • I I I

I

I I

I I

I

I :]

]

1

The road through the camping area is a public road and riders could use this at will. Furthermore, this road-is braided into a number of tracks which gives riders wide discretion if they wished to enforce their rights. It is unlikely that the issue of trail bikes in particular and O.R.R.V.s in general, will be resolved to the satisfaction of both conflicting parties. A wider system of management and legal basis for control must be established. This is covered by recommendations made in 5.11 which would bring O.R.R.V.s under the policy of the National Parks and Wildlife Service.

The Auto Cycle Union of N.S.W. Ltd., the controlling body of moto~.cycling in New South Wales made a submission for inclusion in this report. The Union agrees that limitations should be placed on two and four wheeled vehicles where they cause damage to the environment. Its main interest is to ensure that A.C.U. sanctioned sporting events may take place on private properties with landholder agreement. Here, steps would be taken to ensure that damage to the environment did not occur. The Uriiorr maintains that it takes a responsible attitude to the environment and simply asks for the right to negotiate suitable areas for legitimate sporting activities. In this regard it states that there are more~suit-able areas closer to Lithgow for more intensive motor cycle activities. Given the tenor of this submission, it is unlikely that the major national park recommendations made in this report would create confl ict with organised motor cycle activities. It appears that the major motor cycle use in the Wolgan Valley is on an informal individual and small group basis.

Permanent and long-term campers

Because there are few controls on the land around Newnes, people have been able to establish permanent and long-term camps. There is at least one permanent camp and during this study there was another camp which had been established for 11 months. Whilst such users are a minority their presence is significant.

In a crowded urban society some people will want to camp in natural environments for extended periods. To date this option has been the prerogativeof those who can afford to buy their own land (and thereby also contribute to the problems associated with premature rural subdivisions) or escape to less inhabited northern Australia. tt seems 1napprop-riate to discriminate against those who can not, or do not want to, own land or travel. These people may in fact cause less environmental problems because they do not own land or travel great distances.