Acropolis Essay 2015

-

Upload

fi-maccoll -

Category

Documents

-

view

190 -

download

0

Transcript of Acropolis Essay 2015

A monument to imperialism or an expression of intense religiosity - which of these descriptions of Pericles' refurbishment of the Acropolis do you consider to be more apt?

Fiona MacColl, 2015

In Eumenides, Athena's claim that she 'would find it unendurable not to honour this city among men by making her a city of victory in glorious martial struggles' (Aeschylus, Eumenides, 467), demonstrates the close relationship between Athena the Goddess and the imperial military strength of Athens. This essay will consider the Acropolis as both an expression of intense religiosity and a monument to imperialism, before examining the principal buildings for evidence to support either claim. It will advance the view that, because of the nature of the relationship between Athena and Athens, it is impossible to separate the Acropolis' religious significance from its importance as a monument to imperialism. However, in examining the Acropolis, it must be borne in mind that it is not one building but a complex site containing several different, albeit related, buildings.

The Acropolis, under Pericles, was the greatest religious site of ancient Athens, dedicated to Athena who, though not the only deity revered in Athens, was its patron deity. She was Athena Polias (Athena of the City) and was regarded as founder of Athens after defeating Poseidon and naming the city after herself. Thus, Athena was seen as part of the life-story of the city and of all Athenians. Evidence of Athena's link to the city is seen in the silver tetradrachms which depict the head of Athena on one side, and two of her symbols - the owl and olive branch - on the other, along with the inscription AE which is the first three letters of both the name of the goddess and the city.

Fig. 1. Athenian silver tetradrachm(From Williams, 2015a)

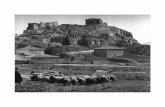

After the Persian war, the Acropolis which had been razed by the Persians in 480 B.C. began being reconstructed in 447 B.C. under Pericles, in a style grander than anything seen before. The rebuilding was done in stone rather than wood as the earlier buildings had been; perhaps not only to safeguard the religious site against future attacks but also to suggest that the Athenian empire was as strong and durable as stone. Thus, it could be argued that the Acropolis has both religious and political significance.

The Greek gods were worshipped 'in the sense of human acknowledgement (nomisdein tous theous)'. When we acknowledge someone, we recognize their presence. What better way to acknowledge the presence of Athena than to build a monument to her? In this way, the Acropolis can be seen as an expression of religiosity. In addition, temples were regarded as homes for the gods to live in. This again emphasises the religious significance of the Acropolis. Within temples, offerings were made, including the first fruits to Athena, a form of offering in which a gift of the products of the earth was given: 'placing fruits or cakes made from grain on altars'. Interestingly, the Acropolis could perhaps be seen as the first fruits to Athena from the citizens of Athens. Afterall, the monuments were made of stone which could be described as products of the earth.

There existed a reciprocal relationship between Athena and her worshippers; the people acknowledged their goddess and, in return, Athena granted them success in their endeavours. As Athena was patron of Athens, the Athenians saw themselves as her favourites. Thus, any success or victory enjoyed by Athens demonstrated the Goddess's approval. In return, the Athenians built sacred monuments such as the Acropolis to Athena.

The monuments on the Acropolis, the construction of which were initiated by Pericles using tribute from the Delian League, may be seen as an expression of the growing Athenian confidence in their imperialistic ambitions but this does not deny any religious significance. In rebuilding the Acropolis after the Persians razed the site in 480 B.C., the Athenians demonstrated their 'debt of gratitude to heaven for the defeat of the Mede'. Pericles' justification for using money given by the League to pay for defenses against the Persians, to fund his building program of the Acropolis was that the money was Athens' by right. The Athenians were not obliged to return the money as long as they maintained defences of the League (Plutarch, Life of Pericles, 12-13). However, the high cost, estimated at four thousand to six thousand talents drew a negative response even from some Athenians. That members of the Delian League were also angry is evidenced by Miletus and Aegina refusing to pay, and Thasos paying less than required. The monies paid to Athens reflect the change in its position, from ally to imperial leader. As tribute could be forced from subject states, it is clear that Athens now saw itself as possessing an empire.

Plutarch's claim that the allies saw the rebuilding of the Acropolis as 'an act of bare-faced tyranny' (Plutarch, Life of Pericles, 12-13) suggests that the building of the Acropolis was less about religion and more about empire-building. His description makes little suggestion of the monuments being seen as expressions of intense religiosity. Rather, he speaks of them 'gilding and beautifying our city'. However, it must be remembered that in ancient biographies, events and speeches were often made up to portray the character of the central figure as seen by the biographer. As Plutarch was Roman, writing long after the events, it seems possible that he would present Pericles as an empire-builder; a trait considered admirable in Ancient Rome.

Thus, the decision to rebuild and improve the Acropolis can be seen as linked to the growing importance of Athens. The monuments would 'bring [Athens] glory for all time' (Plutarch, Life of Pericles, 12-13). However, as Athena was the patron goddess of Athens, and Athens was the favoured city of Athena, the glory of one was the glory of the other.

The Acropolis was presented as an expression of the power of Athens. By showcasing the primacy of Athena over the other gods, and especially Apollo who was the central figure for the Delian League and patron of Delos where the treasury had formerly been located, Athens was not just asserting the religious significance of its goddess but also of its state.

Three of the principal surviving buildings - the Parthenon, Propylaea and Athena Nike - were initiated during Pericles' lifetime and strongly focus on Athena, perhaps suggesting that these monuments were seen, at least in part, as an expression of intense religiosity towards the patron goddess of Athens.

The Parthenon, however, while the grandest of the monuments on the Acropolis, was not a temple. It had neither a dedicated priestess, nor the usual altar outside, facing the front entrance. While it was not unusual for Greek temples to function as banks, it is perhaps significant that the Parthenon took its name from the smaller chamber - the parthenon or maidens chamber where the bank was located. This may suggest that the primary importance of the Parthenon was its role as treasury; and as such it was more a monument to Athenian imperialism than one of religious significance.

The Parthenon was built to impress. It was constructed of Pentelic marble and was larger than other temples being 8 x 17 columns in size, rather than the usual 6 x 13 columns. Inside the main body of the building (cella) was a huge gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos which replaced the usual altar. It was designed to impress, not to inspire reverence and so could be seen as a sign of Athen's power and that of its goddess; a sign of Athens' confidence and imperial ambitions. The statue was profoundly militaristic, holding a Victory and a spear, with a shield at her feet, which again suggests the military might of both the Goddess and her city.

Fig. 2. Nashville Parthenos (copy of Athena Parthenos) (From Williams, 2015a)

The Parthenon's metopes can also be seen as symbols of imperialism, depicting symbolic battles; gods battling giants representing the battle between good and evil, Greeks battling Amazons and Trojans demonstrating the military strength of Athens, and Lapiths fighting Centaurs representing the Athenians against the Persian barbarians. As the metopes were on the exterior of the Parthenon and easily seen, they can fairly be described as symbols of imperialism, designed to reinforce the political propaganda of Athen's military might.

Fig. 3. Parthenon - south metope 31 Lapith and Centaur(From Williams, 2015a)

In addition, the continuous sculpted frieze that goes around the inner columns on the exterior of the Parthenon is a typically Ionic feature, perhaps emphasizing Athens' political position as part of Ionia. While the frieze can be seen as nothing more than a decorative feature, it can also be interpreted as an attempt to demonstrate the link between Athens and Ionia, thus validating its claim as leader of an empire that included Ionia.

Fig. 4. Parthenon frieze(From Williams, 2015a)

The Propylaea is another grand monument, designed to impress visitors though it has no overt religious significance. This huge, five-columned entrance to the Acropolis demonstrates the grandeur of the state, supporting the view that the Acropolis is more a monument to Athenian imperialism.

Fig. 5. Propylaea(From Williams, 2015b)

Under Pericles, the Propylaea was re-aligned to face the Isle of Salamis - the site of the Greek victory against the Persians. This emphasises Athenian imperial strength. However, within the Acropolis, the Propylaea looked directly onto Athena Promachos, suggesting religious importance. Thus religion and state are seen to be linked.

Athena Promachos was a huge bronze statue of Athena, created from the spoils of the Persians who landed at Marathon in 490 B.C., and built after the Greek's victorious battle at the River Eurymedon. It used military imagery such as a spear and helmet, and the name Athena Promachos means Athena Who Fights in the Foremost Ranks. Thus, it could be seen as a sign of the victory at Eurymedon, and growing confidence of the Athenians.File:National Archaeological Museum of Naples - Athena.jpg

Fig. 6. Athena Promachos(From Brown, 2012)

It was tall enough to be seen from sea and so would impress members of the Delian League who came to Athens to get their cases heard in the law courts, or exchange currency; acts which the Delian League was required to do by Athenian law. In this way, it was a sign of imperial strength but also a sign of the power of Athena in her martial aspect. As she was the patron goddess of the city, her strength and the city's strength were one and the same.

The temple of Athena Nike is of special note as it was located just outside the entrance to the Acropolis and was immediately seen upon approaching the Acropolis. The east frieze of the temple allegedly depicts Athena standing in the centre of a group of gods, emphasising the supremacy of Athena over the other gods, and by implication, the supremacy of Athens over other Greek states.

Fig. 7. East frieze of Athena Nike(From Palagia, 2005)

In addition, the frieze depicts battles between the Persians and Athenians. Thus, it could be seen as a monument to the imperial military strength of Athens.

Fig. 8. Frieze depicting Greeks and Persians fighting(From Williams, 2015b)

In contrast, the Erechtheion, built after Pericles' death in 429 B.C., focused on the archaic grouping of gods, and Athena in her earlier Athena Polias role, perhaps suggesting a move away from Pericles' religious-military vision. The irregular shape of the temple was likely the result of the wish to encompass different sacred spots, including altars to Zeus, Poseidon and Hephaestus, as well as symbols representing both Poseidon and Athena's claims to Athens - the shape of Poseidon's trident in the stone and the cult image of Athena Polis, the original and most revered relic of Athena, carved from olive wood.

Fig. 9. Diagram of Erechtheion(From Williams, 2015c)

As the Erechtheion was built later, this could suggest a change in attitude towards the purpose of the Acropolis, focusing more on maintaining older religious traditions and less on portraying Athens as an imperial power which, by this time, was waning. Also, external differences in appearance such as the Caryatid columns and the two porches (prostaseis) suggest a move away from Pericles' original vision for the Acropolis.

Fig. 10. Erechtheion, Caryatid Porch(From Williams, 2015b)

In conclusion, it is reasonable to see the Acropolis as a

monument to imperialism, and supporting evidence such as the many

military images on the monuments or the realignment of the

Propylaea to face Salamis, emphasising the military strength of the

Athenian Empire, is compelling. However, Athens' position as the

city of the goddess, Athena, and its political ambitions cannot

easily be separated. The Acropolis was rebuilt, at least in part,

to honour Athena after the victory at Salamis. As patron of Athens,

it was both the goddess and the citizens who won the war. This was

a 'holy' city; one in which 'church' and state were undeniably

linked.

Bibliography

AESCHYLUS (2009), Oresteia: Agamemnon. Libation-Bearers. Eumenides,Cambridge, MA. Available at: http://www.loebclassics.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/view/aeschylus-oresteia_eumenides/2009/pb_LCL146.467.xml (accessed on 15.02.2015).PLUTARCH (1915), 'Life of Pericles', in Perrin, Plutarch's Lives 3, London.

BRADLEY, P. (1988), Ancient Greece Using Evidence, Australia.DEACY, S. (2008), Athena. Oxon.ERHMAN, B. (2000), The New Testament, A Historical Introduction to the EarlyChristian Writings, 2nd Ed, Oxford.J.A.C.T. (Joint Association of Classical Teachers) (1984), The World of Athens,An introduction to classical Athenian culture, Cambridge.KUBALA, L. (2013), 'The distinctive features and the main goals of Athenianimperialism in the 5th Century BC ('Imperial' policies and means of control in the mid 5th century Athenian Empire)', Graeco-Latina Brunensia. Available at: https://digilib.phil.muni.cz/bitstream/handle/11222.digilib/127202/1_GraecoLatinaBrunensia_18-2013-1_11.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24.01.2015).LOW, P. (2008), The Athenian Empire, Edinburgh.PALAGIA, O. (2005), 'Interpretations of two Athenian friezes', in Barringer andHurwit (eds), Periklean Athens and its Legacy.PSARRA, S. (2004), 'The Parthenon and the Erechtheion: the architecturalformation of place, politics and myth', in The Journal of Architecture 9. Available at:http://faculty.risd.edu/bcampbel/H101-2011Psarra-The%20Parthenon%20and%20the%20Erechtheion%5B1%5D.pdf) (accessed on 02.02.2015).SILVERMAN, The Parthenon. Reed College, USA. Available at:http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110Tech/Parthenon.html (accessed on 28.01.2015).WILLIAMS, M. (2015), 'Pausanias on the Erechtheion', in Athens in the Age ofPericles, Class 3 notes, Edinburgh University.

Illustrations

BROWN, E. (2012), Statue of Athena, National Archaeological Museum ofNaples. Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/psalakanthos/4779496809/ (accessed on 13.02.2015).PALAGIA, O. (2005), East Frieze of Athena Nike, 'Interpretations of TwoAthenian Friezes', in Barringer and Hurwit (eds), Periklean Athens and itsLegacy.WILLIAMS, M. (2015a), Athens in the Age of Pericles, Powerpoint Presentation3a, Edinburgh University.WILLIAMS, M. (2015b), Athens in the Age of Pericles, Powerpoint Presentation3b, Edinburgh University.WILLIAMS, M. (2015c), Athens in the Age of Pericles, Powerpoint Presentation4, Edinburgh University..