ACM0510 pCV1 R:00-00 COVER - Philippe Ros · 2017. 2. 1. · sand and make the dangerous journey to...

Transcript of ACM0510 pCV1 R:00-00 COVER - Philippe Ros · 2017. 2. 1. · sand and make the dangerous journey to...

40 May 2010 American Cinematographer

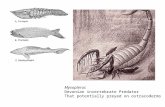

The Disney film Oceans begins with a question, asked by aboy on a beach: “What is the ocean?” The answer thatunfolds in the following 90 minutes takes the form of adazzling nature film that defies categorization. The

movie starts in the sand underwater, with an iguana slowlymaking its way from the ocean floor to the surf, finally puttingone claw on dry land. A little later, a rocket takes off in thedistant skies, and its bright glare is reflected in the iguana’s eye.With a few simple shots, Oceans has visually evoked the storyof evolution.

The film offers many such rich moments. In the sardine-run sequence, an army of dolphins rushes to meet a giganticschool of fish, starting a feeding frenzy that is soon shared withsharks and birds. There is drama when baby turtles hatch in thesand and make the dangerous journey to the nearby water,preyed upon by a flock of rapacious birds along the way. Thefilm is also replete with scenes that reveal man’s kinship withanimals.

The camera is the invisible hero of Oceans. It is placedand moved in novel ways that give the viewer the impression,time and again, of seeing marine life as it has never been seenbefore. The film is the brainchild of Jacques Perrin, who haslong experimented with new formats for nature films, startingwith Microcosmos (AC Jan. ’97), about the world of insects, andincluding Winged Migration, an epic that follows birds aroundthe planet (AC July ’03). Perrin produced Oceans and co-directed it with Jacques Cluzaud, a collaborator on WingedMigration. Cluzaud notes, “These films are a matter of goingever further and continually asking ourselves, ‘What can weinvent?’ Jacques Perrin is not interested in making a film we’vealready seen. We’re always looking for something more.”

WondersoftheSea

21 cinematographers contributespectacular imagery to the naturefilm Oceans, directed by Jacques

Perrin and Jacques Cluzaud.

By Benjamin B

•|•

www.theasc.com May 2010 41

Oceans was a seven-year undertak-ing that involved 340 weeks of shootingspread over almost five years and 54locations, notably several wildlife sanc-tuaries. The film’s 21 cinematographersincluded 10 underwater specialists, andthere were up to six units shootingsimultaneously. The filmmakers alsoresearched, designed and built an arrayof custom camera tools so they couldachieve what they wanted.

Cluzaud recalls that the startingpoint was a script comprising poeticsequences that had working titles such as“the dragon and the rocket,” “caval-cades,” “sea feasts,” “chilling out on thebeach,” “predator” and “the night world.”“Before we set out to shoot, we askedourselves which animals could illustratea specific sequence, and then we selectedthose that seemed the most interesting,”he says. “For example, the beginning ofthe film was called ‘the conquest of theshore,’ and we chose the iguana for itsprehistoric look. Our choices were aboutwhich species would best serve thesequence, and from there, we decidedwhere to shoot and when.”

Cluzaud emphasizes that thefilm’s point of view was defined by adesire to identify with its animalsubjects. “The two key words were ‘prox-imity’ and ‘dynamism.’ We told theoperators to seek out the animals’ gazesand eyelines. We spent a lot of time andeffort to catch an animal’s gaze and filmPhot

os b

y A

lexa

nder

Bug

el, O

liver

Gué

neau

, Pas

cal K

obeh

, Chr

isto

phe

Pott

ier

and

Fran

çois

Sar

ano,

co

urte

sy o

f G

alat

ee F

ilms,

Pat

he P

rodu

ctio

n, N

otro

Film

s, F

ranc

e 2

Cin

ema,

Fra

nce

3 C

inem

a, J

MH

/TSR

.

Opposite: AnAsianSheepsheadWrasse is one ofthe many exoticsea creaturesfeatured inOceans. Thispage, top:Weddell Seals inthe Antarctic.Middle andbottom: Diversexplore colorfulnooks whileswimmingthroughunderwatercaves inHienghiène,New Caledonia.

42 May 2010 American Cinematographer

it like a character. I think what distin-guishes this film in particular is that weare dealing with characters: you experi-ence the animals differently because theyare filmed differently.”

Identifying with the animals alsomeant “being a fish among the fish,” hecontinues. “There are very few staticshots. The principle was to always bemoving because living things move —even the tiny feet of a starfish aremoving, however slowly. With fastspecies such as dolphins, the questionwas what could we invent to follow themat full speed both above and below thewater. We created the Thetys headabove, and the Torpedo and the Polecambelow. We’ve seen whales, dolphins andsharks underwater before, but never atsuch a speed.”

Cinematographer Philippe Rosshot Oceans’ night sequences, amongothers; was involved in developing somecustom tools; and supervised the work-flow as digital-imaging director. Theproduction decided to shoot Super35mm for material above the water, andhigh-definition video for underwaterwork except for slow-motion material.Ros explains that the main reason forchoosing HD was the ability to runcassette loads of 50 minutes. Theproduction designed and built fourautonomous underwater housings forthe diver operators. The housings were

◗ Wondersof theSea

Top: Anintrepid

cameramancaptures a

bold shot of agreat white

shark offMexico’s

GuadalupeIsland. Middle:

Thefilmmakers

take viewersstraight into a

formation ofbigeye trevally

in the IndianOcean’s Cocos

Islands.Bottom: A

clownfish getshis close-up inNouméa, New

Caledonia.

outfitted with Sony HDW-F900/3sshooting in HDCam format, whichwas the HD standard in 2005, whenshooting began.

Speedy animals were shot from aboat, and Sony HDC-950s were usedin those instances because the camerahead could be separated from thecamera body; the camera heads wereplaced in small capsules that were thenfitted to custom-designed Polecams orTorpedoes linked to the boat via fiber-optic cable, a technology the filmmak-ers refined over a year of development.The Polecam consisted of a submergedcamera capsule attached to a large trian-gular support fastened to the side or theprow of the boat. The Polecam couldnot be used to shoot backwards becausethe boat’s wake would spoil the shot, soit was used to capture side angles of thecreatures right below the surface of thewater. For shots from the back of theboat, camera capsules were placed inTorpedoes that were attached to thestern with a long, metal leash; thisarrangement allowed for shooting as faras 100 meters away and avoided theboat’s wake.

The Panavised Sony cameraswere outfitted with Zeiss 6-24mm and17-112mm DigiZooms. In order to getthe proximity requested by the film-makers, the dominant underwater focallength was about 7mm, which Ros saysis equivalent to about 18mm in 35mm.The lenses were often set to the hyper-focal distance. Underwater cameraoperator René Heuzey recalls, “Thedirectors really did want us to be ‘a fishamong the fish.’ The fish could not beshown to be curious of the camera. Wealso had to avoid seeking out the fish —the image had to float by itself. Youcouldn’t feel the camera chasing afterthe animal. Another rule was to alwaysshoot with natural lighting.”

Heuzey shot a unique sequencewhile moving with a large blanket octo-pus that unfolded an orange cape as itglided above the ocean floor. “I call that‘the Batman shot,’” he says. “To get theimages, I shot for 12 days, spendingthree or four hours underwater per day.

First, you have to gain the animal’sacceptance so he understands you’re nota predator. You don’t want to startle theblanket octopus, or it will let go of its inkand change color.” Heuzey often swamin the direction of the current, using theflow to help stabilize the image. Henotes that he was given a very specificshot list. “For example, the directorsasked me to match the blanket octopusto the sails of a sailboat featured in

another shot. That took me a couple ofdays.”

Working with wild animalsdemanded patience and persistence,and produced many surprises. Heuzeyremembers an orca that sought him outafter he had returned to his boat. Hedove back in, and the orca led him awayfrom the boat and gave him a privateshow. “When I blew bubbles, he blewbubbles, and when I nodded, he

said they wanted a close-up for the edit,so we went back the following year andwe got the shot!

“The work was a mixture of joyand frustration,” he continues. “It wasfantastic at certain moments, andcompletely depressing at others.Sometimes I just missed an extraordi-nary shot because I was a little too tight,and I was only too tight because I’dzoomed in for no particular reason rightbefore the whale jumped.” Many of themost spectacular jumps were shot at 50or 100 fps. Drion used an Easy Lookunit with the video assist to simulate theslow-motion playback. Although theland-based footage was shot in 3-perfSuper 35mm, less predictable materialwas shot in 4-perf to allow for reframingin post.

Drion also remembers momentsof bliss: “You’re there with hundreds ofdolphins jumping around you, andyou’ve been looking for this shot for twoyears. You’ve already seen dolphin caval-cades, but they didn’t have the sameenergy, the same sea, the same every-thing! There’s a kind of miraculoussynchronicity, and that’s also due to thedirectors, who wanted this shot and sentyou back to the same spot the followingyear because you didn’t get what theyneeded the first year. It’s stubborn workat every level.”

Drion was also the operator for a

44 May 2010 American Cinematographer

◗ Wondersof theSea

Top left: A cloud of krill. Bottom left: Filming sea nettles in Monterey Bay, Calif. Above: Forshots taken from the back of boats, camera

capsules were placed in Torpedoes that wereattached to the stern with a long leash, which

allowed the filmmakers to avoid the boat’s wake while shooting.

used a variety of Angenieux zoomlenses, including the Optimo 17-80mm, the Optimo 24-290mm and anHR 25-250mm.

Drion recalls that his jobinvolved a blend of patience, guessworkand reactivity. As example, he cites theshot of a huge shark leaping out of theocean, capturing a bull seal in its jaws.“We spent a lot of time on that shot,and the game was to follow a seal,hoping it would be eaten by a shark,” hesays. “That shot was the result of stub-bornness, ours and the production’s! Wehad to throw away 20 or 30 1,000-footloads, unprocessed. We didn’t get theshark the first year, so we went back inthe second year and got it. Then they

nodded. It was incredible — I felt likewe knew each other.”

The production’s main filmcamera was the Arri 435, which wasused on boats, in helicopters and onland. An extensively modified Arri 2-Bwas used in the tiny Birdy Fly heli-copters that could hover above whalesand other large mammals without star-tling them. Much of the above-waterwork was done with a 435 on a smallcrane with a Thetys, a rugged, gyrosta-bilized head designed and built by theproduction. Because whales and othermammals are less threatened by smallerboats, the Thetys rig was often put in aninflatable Zodiac. Operating the Thetyswas cinematographer Luc Drion, who

46 May 2010 American Cinematographer

◗ Wondersof theSeaviolent storm sequence, which showslarge boats dwarfed by powerful waves.In one shot, a warship is filmed head-onand then completely obscured by a huge,oncoming wave. Drion reveals that thescary image was shot from a helicopter.“The waves were 15 meters [49'] high.Because they were spaced far apart, we’dgo down above the water when the wavewas low, and the pilot would look behindhim to get back up before the next wavearrived.” Drion’s Arri 435 was in a gyro-scopic Stab-C mounted on a sidebracket. “I had absolute trust in the heli-copter pilot. To get the waves to hide theship, I would say, ‘Lower, lower,’ butwhen he refused, I didn’t insist! It wasimpossible to use a rain deflector, so thecamera assistant, wearing a harness,would lean out of the chopper and wipethe lens by hand.”

Part of an especially memorableunderwater night sequence was shot offa dock. The protagonists are squillas andcrabs, and the filmmakers created anunderwater dolly setup complete withtracks to follow “Joe the crab” as hehustles along the underwater reef. To keythe scene, Ros set up Dino lights shiningdown into the water through cookies.The Dino bulbs were made to flickerindependently to emulate dappled wavepatterns underwater. The sequence alsocontains a macro shot of the squilla’sextraterrestrial eye, which was shot in ashallow pool that afforded more lightingcontrol.

One of the major challenges inpost was matching HD to the filmfootage, which was scanned at 4K by ateam (including Tommaso Vergalo, JuanEveno and François Dupuy) atDigimage Cinema in Paris. The resultslook seamless, which is especiallyimpressive given that most of the digitalfootage was shot in the 8-bit HDCamformat, which has a recorded horizontalresolution of 1,440 pixels. Ros empha-sizes that he designed the workflow withthe final goal of 2.40:1 exhibition inmind. To create an HD image thatwould match the 35mm as closely aspossible, he did extensive testing andworked in coordination with Olivier

Top: To captureside angles of

animals justbelow the

surface of thewater, the

filmmakersused the

Polecam rig, asubmerged

camera capsuleattached to a

large triangularsupport

fastened to theboat. Middle:

Macro shots ofsquillas werecaptured in ashallow poolthat affordedmore lighting

control.Bottom: A

radio-controlledBirdy Fly

helicopter wasused to capture

dynamicfootage of

whales andother

mammals.

www.theasc.com May 2010 47

Garcia and Christian Mourier todevelop a series of custom gammacurves and scene files for the video oper-ators to use. The low-contrast curveswere varied to address different lightingconditions. To accommodate differentsea coloring, Ros notably reduced andisolated the blue or green vectors in theF900 multi-matrix menu. He alsotweaked the levels in the detail menu formurkier scenes.

Ros and his team created twosimple knobs on the underwater hous-ing to apply this range of settings. Oneknob was for the ocean color, and theother for the scene’s contrast and visibil-ity. Each knob had five settings, creating25 possible combinations, or, as Rossays, “25 digital film stocks.” MatchingHD to film, he continues, “had twocomponents: preserving the highlightsand getting maximum resolution whenshooting, and reducing noise in post. Inproduction, we strove to have the rightgamma curve for the highlights, theright saturation for the sea, and the rightsetting in the detail menu, usuallybetween -45 and -60, for the scene.

“I knew that up-converting fromHD to 4K in post would work if theimages had little noise, but the thing wecouldn’t correct for was the solarizing

effect, when you lose detail in thewhites. So we always chose to protectthe whites, even if it meant more noise.But when we didn’t have strong high-lights in the image, we used curves thathad less noise. That’s why we hadseveral gamma curves.”

Key for Ros was the constantcommunication between productionand post, and the constant verificationof the dailies by the cinematographers,the digital-imaging technicians (led byFrançois Paturel) and the colorists. Rosalso instituted a daily testing procedure

that accustomed the operators to evalu-ate the rendering of a test chart. “Abovea certain threshold, around 2K, it’s notthe number of pixels that matters, butthe quality of your pixels,” he observes.“That’s why we did a lot of work oncertain menus and, especially, why wediminished the level of noise. When youcan get rid of the noise, each pixel iscleaner, and you can increase your MTFbecause you can then discern detail.”

Def2shoot in Paris applied aproprietary noise-reduction process tothe HD material and a degraining

The filmmakersemployed anunderwaterdolly to greateffect,especially for anight sequencethat follows acrab hustlingalong a reef.

process to the 35mm. The HD up-conversion to 4K was done after thedigital grade, using a custom Digimageprocess. Digimage also applied a propri-etary process called “wide range” to getslightly stronger whites in the filmout,and created multiple digital negatives,which were used to print positivesdirectly so as to avoid the loss of twoextra generations. For the DCP master,selective focus was applied to 200 shots

as a way of emphasizing certainelements in the frame.

Perrin asked an old friend, cine-matographer Luciano Tovoli, ASC,AIC, to shoot a few fictional sequencesthat are absent from the U.S. version ofthe film, and also to supervise the DI atDigimage. “Jacques said he wanted aneye to harmonize the different footageaccording to the vision of the directors,”says Tovoli, who spent 12 weeks on the

grade with Ros and colorist LaurentDesbruères. “I was lucky to work closelywith Laurent and Philippe,” says Tovoli.“As always with Perrin productions, theatmosphere was one of honesty andprofound respect for the professionalismof others.”

The main challenge, notes Tovoli,was matching disparate footage cuttogether in a scene. “One scene couldcontain shots done three years apart indifferent seas — they were editedtogether to look like reversal shots,”explains Tovoli. Desbruères adds thatanother challenge was the multitude ofocean currents, which created variegatedcolors, sometimes even in the same shot.He cites the sardine run as an example.“It’s amazing — you get a variety ofnuances from blue to cyan and thenmagenta which appear with smallchanges of depth.” Another difficultycame from murky waters, which thecolorist brightened by enhancing beamsof light.

◗ Wondersof theSeaDesigned and

built by theproduction, the

rugged,gyrostabilized

Thetys headwas often set

up in aninflatable

Zodiac, whichwas less

threatening tosea creatures

than largerboats.

48

Desbruères graded the film on aDaVinci Resolve, spending a lot of timedrawing dynamic grading windows tocompensate for constantly changinghues and luminosity. He remembersthat one shot moving toward the surfaceof the sardine run required almost 60tracking windows. “A window may onlylast 10 frames and then fade out,” henotes. Sometimes he would outline asmall creature in the frame to make itmore visible onscreen. Desbruèresremembers the intense grading sessionsfondly: “I didn’t feel the fatigue becauseI was at the heart of something thattransported me.”

Tovoli recalls that the gradeevolved with time. “Our first timing waspretty contrasty, with beautiful blacks,but the directors didn’t want too muchcontrast underwater because they didn’twant it to be scary,” he explains. “Forthem, the color of the ocean was thecolor of life. They wanted a blue thatisn’t heavy, that is transparent, agreeable

and light, so we chose the lightest color,because color can become threatening.We never left any impenetrable darkzones, even in the night sequence withpredators.”

Perrin has described Oceans as “anunderwater wildlife opera.” Whateverthe genre may be, one word that arosefrequently during AC ’s interviews was“collaboration.” After initial shoots withthe directors, many cinematographerswere trusted to continue on their own.“We were both amazed and yet notsurprised by what they brought back,because we were on the same wave-length,” says Cluzaud. “Having manycinematographers meant having manydifferent ways of filming, and that givesthe film an incredible richness.”

“I never believed filmmaking wasa collaborative art,” Tovoli confesses,“but this film proved me wrong. Putting21 cinematographers and two directorsin harmony, now that is collaboration!”

●

49

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.40:1

Super 35mm and High-Definition Video

Super 35mm (4- and 3-perf):Arri 435, 235, 2-B, 2-C, 35-3;Aaton 35-IIIAngenieux, Zeiss and Cooke lenses

Kodak Vision2 50D 5201, 250D 5205, 100T 5212, 200T 5217, 500T 5218;Fuji Super F-64D 8522

HD:Sony HDW-F900/3, HDC-950,F23Zeiss and Panavision lenses

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383