Ackermann+Devoy ‘The Lord of the Smoking Mirror’: Objects Associated With John Dee in the...

Transcript of Ackermann+Devoy ‘The Lord of the Smoking Mirror’: Objects Associated With John Dee in the...

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/ locate/shpsa

‘The Lord of the smoking mirror’: Objects associated with John Deein the British Museum

Silke Ackermann, Louise DevoyDepartment of Prehistory and Europe, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, United Kingdom

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Available online 22 December 2011

Keywords:John DeeBritish MuseumObjectsDivinationMagicCollections and collectors

0039-3681/$ - see front matter � 2011 Elsevier Ltd. Adoi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2011.11.007

E-mail addresses: [email protected] 2007, directed by Shekhar Kapur and produced by2 In the older literature these objects are also referre3 British Museum, Room 1 (Enlightenment), floor ca

a b s t r a c t

Six objects associated with the magic practices of John Dee have been held within the collections of theBritish Museum for many decades. These objects include three wax seals, an obsidian mirror, a gold discand a crystal ball. In this paper we review the provenance and possible association of these artefacts withDee by comparing their features to the descriptions and diagrams set out in Dee’s manuscripts. Althoughwe come to the conclusion that a direct link between these objects and Dee remains to be proven, we alsouncover a complex world of collectors whose avid interest in Dee contributed to the collection of objectsassembled today, which continue to reinforce Dee’s reputation as a magician.

� 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

When citing this paper, please use the full journal title Studies in History and Philosophy of Science

1. Introduction

Scene: In the Round Reading Room of the British MuseumDee’s mirror. I glanced along the body, but the black mirror wasnowhere to be seen. They’d stretched him naked on his back, hisbody arched over arms bound beneath him. Blood had pooledand thickened on the shelf top, dripping in slow, steady drops.Just below his ribcage, a wide slash gaped across his abdomenlike an obscene mouth . . .She’d killed him to consecrate the mir-ror. (J. L. Carrell, The Shakespeare curse, 2010, p. 335)

Apart from being the subject of countless scholarly publications,the character of John Dee—and especially his dealings with magic—continues to fascinate the wider public. In the last few years alonehe has appeared in numerous films and books, from the crystal-gazing magus seen in Elizabeth: the Golden Age1 to the cautious sagetrying to prevent Shakespeare from invoking evil spirits in his plays,as told in Carrell’s novel quoted above. The same appeal can be wit-nessed in the British Museum, where gallery talks and lectures on

ll rights reserved.

(S. Ackermann), ldevoy@britishmUniversal Pictures and Working Titd to as OA. 105–07.

se 20.

John Dee are regularly oversubscribed and where ever so often visi-tors request a viewing of the ‘secret room’ of Dee’s divination tools.Sadly, such a treasure trove does not exist, but we do indeed have asmall group of objects associated with John Dee: three inscribed waxdiscs (reg. no. 1838,1232.90.a–c),2 an obsidian mirror with a match-ing case (reg. no. P&E 1966, 1001.1), a gold disc inscribed with a dia-gram of the ‘vision of the four castles’ (reg. no. P&E 1942, 0506.1) anda crystal ball or ‘shew stone’ (reg. no. P&E SLCups.232)—all of whichare on display3 and can be viewed online (British Museum, 2011).But if one were to examine the ‘biography’ of these diverse objects,which have entered the museum by different routes at differenttimes over the past 250 years, one would find that their provenanceand association with Dee is by no means as secure as one mightthink. This paper aims to trace the life story of these artefacts fromtheir origins to their eventual display at the British Museum (Fig. 1).

2. The three wax discs

In the collection of the British Museum are three wax discs: alarger one with a diameter of 23 cm (reg. no. P&E 1838,

useum.org (L. Devoy)le Films.

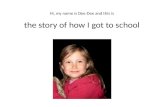

Fig. 1. The group of Dee-associated artefacts (reg. nos. from left to right: P&E1966,1001.1; P&E SLCups 232; P&E 1838,1232.90.c (damaged), P&E 1838,1232.90.b(complete), P&E 1838,1232.90a (large); P&E 1942,0506.1). �Trustees of the BritishMuseum (image reference AN37447001)

Fig. 2. The AGLA cross and table of seals, as sketched by Dee (British Library, MSSloane 3188, fol. 10r). �The British Library Board (MS Sloane 3188)

540 S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549

1232.90.a) and two smaller ones with a diameter of 12.5 cm (reg.no. P&E 1838, 1232.90.b–c). The size of, and inscriptions on, these‘seals’ bear a striking similarity to the instructions given by the an-gel Uriel during a session held on the afternoon of Saturday 10March 1582, as recorded by Dee:

Uriel: . . .you must use a fowre square Table, two cubits square:Where uppon must be set Sigillum —D—i—v—i—n—i—t—a—t—i—s Dei . . .which isallready perfected in a boke of thyne: Blessed be God, in allhis Mysteries, and Holy in all his works. This seal must not beloked on, without great reverence and devotion. This seale isto be made of perfect wax. I mean, wax, which is clean purified:we have no respect of cullours. This seal must be 9 ynches indiameter: The rowndnes must be 27 ynches, and somewhatmore. The Thicknes of it, must be of an ynche and half a quarter,and a figure of a crosse, must be on the back side of it, madethus [diagram of AGLA inscribed in crosses sketched by Dee].(British Library, MS Sloane 3188, fol. 10r)

The great seal was to be placed in the centre of a table madefrom sweetwood with the four legs balanced on smaller versionsof the seal, as sketched by Dee on the same page (Fig. 2).4

Further instructions on how the diagrams should be inscribed onthe seals were given by the angel Michael a little later (British Li-brary, MS Sloane 3188, fol. 17r–20v). First, an outward circle dividedinto 40 equal parts to represent the true circle of God’s eternity hadto be inscribed. Dee then records that 40 white creatures in longwhite silk robes appeared and fell to their knees in front of Michael.One by one, the creatures opened their breasts to reveal combina-tions of letters and number such as G9, 7n and 22 h. After the sessionhad ended, Uriel reappeared to the scryer, Edward Kelley (alsoknown as Talbot), and instructed Dee to make some corrections tothe seal as the scryer had omitted to declare all the required knowl-edge (ibid., fol. 20v). Michael then continued with his instructionsand described a series of nested heptagons, each one containingabbreviations or the full names of angels that Dee is instructed to re-cord on the seal (ibid., fol. 20v–29v). The resulting seal, which issketched on fol. 30r of the same manuscript, first gives the namesassociated with a vision of gold baskets. These names are not writtenin full, but are inscribed as capital letters accompanied by crosses, asinstructed by Michael. This is followed by letters inscribed aroundthe perimeter of the first heptagon which give the names of angelswhen arranged in a square pattern of seven by seven. Underneath

4 This wooden table does not appear to have survived, but a marble copy is on display at(1999) the table was probably produced after the publication of Casaubon (1659), whichpresented to the Bodleian Library in 1750 by Richard Rawlinson, who claimed that the ta

each side lie angelic names. The next inward entwined shape fea-tures the names of young women dressed in green silk in the trian-gular corners, while the names around the sides are those of youngmen who appeared bearing pieces of purified metals such as gold,silver, copper and mercury. Then there are two groups of children:girls in white silk robes in the penultimate heptagon, followed by lit-tle boys in purple silk robes forming the names on the innermostshape. For the central space, Michael’s instructions are more com-plex. The letters for one name, Zabathiel, are written around theinnermost heptagon, with an abbreviation for the last two letters.Five remaining names are used to encircle a pentagram whichfeatures a central cross surrounded by the seventh name, Levanael.Uriel concludes the vision with an explanation: ‘These Angels are theangells of the 7 Circles of Heven, governing the Lightes of the .7.Circles’ (ibid., fol. 29v) (Figs. 3–5).

As close comparison shows, the inscriptions on the great waxdisc are virtually identical with the diagram in Dee’s manuscript.The only difference is the number of crosses inscribed on the armsof the two heptagons: on the wax disc the number has been in-creased. The two small discs are more worn and have sectionswhich are either illegible or have broken off at some point in theirhistory. Nevertheless, one can still find a few minor differences be-tween the Sigillum Dei diagram and the engravings on the smallseals. For example, there are faint concentric rings within the outercircle and around the central pentagram, as well as a reduced num-ber of serifs and crosses, although the letters H and Z still have

the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford (inv. no. 15449). According to Bennettfeatured an engraving of the diagram seen on the table. The object was originally

ble had once belonged to the astrologer William Lilly (1602–1681).

Fig. 3. Dee’s diagram of the seal (British Library, MS Sloane 3188, fol. 30r). �TheBritish Library Board (MS Sloane 3188)

Fig. 4. The front of the great wax seal (reg. no. P&E 1838,1232.90.a). �Trustees ofthe British Museum (image reference AN36990001)

Fig. 5. The reverse of the great wax seal featuring the AGLA cross (reg. no. P&E1838,1232.90.a). �Trustees of the British Museum (image reference AN968312001)

5 Letter dated 15 October 1692 from Mr Richard Lapthorne, of Hatton Garden, London,Report V (1876), p. 383.

S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549 541

their distinctive features of a wide spread and dropped final strokerespectively. On the reverse of the seals there are no inconsisten-cies between Dee’s sketch and the engraved AGLA crosses. In sum-mary, there are no significant differences between the engravingsand Dee’s own handwritten interpretation of the angelicinstructions.

But are we to conclude from this correspondence that the ob-jects were made by Dee himself, or at least made under his super-vision during his lifetime, and used for the described purposeduring scrying sessions? The discs themselves do not appear tobe mentioned any further in Dee’s manuscripts, nor are they listedamongst his damaged or stolen possessions after his return fromBohemia (Dee, 1592, chaps.7 and 8). Nor do they appear to havebeen discussed by the collectors of Dee’s books and manuscriptsafter his death—until 1692 that is, when an eyewitness recalls:

I had a short view of Sir R. Cotton’s Library. It is scituated [sic]adjoining to the House of Commons at Westminster, of a greathighth, and part of that old fabric . . . I had not the time to lookinto the books; some relicts I took notice of, besides the books;viz . . . I also saw Dr. Dee’s instruments of Conjuration, in cakes ofbees wax almost petrified, with the images, lines, and figures,on it.5

Unlike some other collectors, who sought to acquire Dee’s writ-ings on what one might now call ‘occult matters’, Sir Robert Cotton(1571–1631) appears to have had very little interest in these sub-jects, despite Dee’s visits to Cotton House in Westminster(Huffman, 1988, p. 33). However, he clearly regarded Dee’s re-nowned library as a rich source of books and manuscripts for hisown burgeoning national library, for which he sought royal ap-proval (Handley, 2008b). As Colin Tite has shown, Cotton acquiredmaterial from the collection of John Dee both during the 1625and 1626 sales and during earlier disposals, and the Cotton Libraryhas some 30 manuscripts from Dee (Tite, 1994, p. 19). The Cottonfamily’s interest and investment in Dee’s work continued for sev-eral decades. In the 1650s, Cotton’s grandson, Sir John Cotton(1621–1702) persuaded the French scholar Meric Casaubon(1599–1671), who was a guest in the Cotton household, to

to Mr Richard Coffin at Portledge, North Devon. Historical Manuscript Commission,

Fig. 6. View of the mirror and leather case (reg. no. P&E 1966,1001.1). �Trustees ofthe British Museum (image reference AN32722001)

542 S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549

transcribe and publish Dee’s scrying manuscripts which were rap-idly disintegrating.6 Rather reluctantly, Casaubon fulfilled his host’swishes, and the resulting publication, A true and faithful relation ofwhat passed for many years Between Dr. John Dee and some spirits(1659), created a permanent record of Dee’s angelic conversations(Serjeantson, 2004; Clucas, 2006).

Whether Cotton’s acquisitions included the wax discs orwhether these were later added to the collections has so far re-mained unclear. There is no record of these objects in the early cat-alogues of the Cottonian Library dating from 1696, where only theletters and manuscripts of Dee are mentioned.7 We have no furtherevidence for these wax discs until 1703, when similar items are men-tioned in Wanley’s catalogue of the Cottonian Charters. At the time,the Anglo-Saxon scholar Humfrey Wanley (1672–1726) (Heyworth,2004) was under the patronage of Robert Harley (1661–1724), Speak-er of the Commons (Speck, 2007), and was commissioned to report onthe condition of the Cottonian Library, bequeathed to the nation in1701 as an Act of Parliament.8 In this catalogue we find two intrigu-ing references. The first entry mentions ‘3 Large Seals of Wax, one les-ser and fragments of 3 others’ (British Library, MS Harley 7647, fol.11r, under ‘Vespasianus’). The second entry lists various charters,maps etc, ‘Lying near, or upon, Dr Dee’s conjuring Table’ (ibid., fol.12r, under item 44). A further reference can be found in R. Widmore’scatalogue of the Cotton Charters, compiled around 1750. A conclud-ing note to ‘Cartae in loculo XVIIII’ adds, ‘And beside, the forms ofsome Princes Seals in Metal, and two or three Cakes of Wax Mark’dwith figures’ (ibid., fol. 52r). A handwritten catalogue of ‘Chartersand Rolls in the Cottonian Collection’, compiled in the late eighteenthcentury by Samuel Ayscough (1745–1804), a cataloguer at the BritishMuseum, gives the first explicit reference to Dee in relation to thewax seals: ‘Three Cakes of Wax marked with magical names andnumbers which were used by John Dee in his conversations withSpirits.’9

In March 1838 the wax discs were transferred from the Depart-ment of Manuscripts to the Department of Antiquities, the objectsthereby separated from the associated manuscripts.10

It is tempting to conclude that the explicit demand of the angelto make the wax discs according to the instructions given (and notjust to record these instructions on paper) might have promptedDee to comply. There is, indeed, a very close correspondence be-tween the inscription on the discs and the diagram of the ‘seals’in Dee’s manuscript, so whoever made the discs is likely to havehad the manuscript or a faithful copy of the diagram in front ofhim. However, in the absence of any evidence for the existenceof the discs before 1692 we cannot be absolutely certain that thediscs do, indeed, originate from Dee’s lifetime.

3. The obsidian mirror

This object, a highly polished black stone measuring 22 cm inheight and 18.4 cm in diameter (reg. no. P&E 1966, 1001.1), is

6 In the lengthy preface to his work, Casaubon outlines the Cotton family’s interest in Dextensively on theological and antiquarian topics and was a suitable choice of scholar to

7 Smith (1696). An English version is also available: Smith & Tite (1984). Dee’s letters a8 See British Academy and Royal Historical Society Joint Committee on Anglo Saxon Ch9 British Library, Add. MS 43502, fol. 211r, listed as item XVI.5a. A handwritten note by c

of Antiquities in 183 . . ., FM.’10 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Department of Antiquities Regis

the Department of MSS to the Department of Antiquities in March 1838.’11 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1966, 1001.1 (Part12 Letter from the Keeper R.L.S. Bruce-Mitford to Bishop Stannard, 28 October 1966. Brit13 For a detailed review of the previous owners, see Tait (1967, pp. 200–203).14 There are two additional labels on the tooled leather case. One, written in Walpole’s ha

Hudibras, Part 2. Canto 3 v.631. Kelly did all his feats upon The Devil’s Looking-glass, a Stoquote from Samuel Butler’s Hudibras (1663): ‘Kelly did all his feats upon/The Devil’s Lookideep.’

one of Dee’s most iconic artefacts (Fig. 6). It was purchased bythe British Museum from the Reverend Robert William Stannardin 1966 for the sum of £750.11 The Trustees were clearly pleasedwith their new purchase:

We are delighted with this acquisition and I believe it hascaused the Trustees more pleasure than anything else for quitea time. They were really enthusiastic about it.12

Prior to being in Stannard’s possession, the mirror had passedthrough the hands of five owners, all of whom can be identifiedthrough auction records and surviving notes which have accompa-nied the object between buyers13—the most prominent of whom isthe author, antiquarian and politician Horace Walpole (1717–1797)(Langford, 2008). From this point onwards (or rather, backwards) theprovenance becomes less certain and the object’s history is entirelydependent upon claims made by Walpole himself. On a small labelpasted to the mirror’s leather case is the following handwritten note:

The Black Stone into which Dr Dee used to call his SpiritsV. his bookThis Stone was mentioned in the Catalogue of the Collection ofthe Earls of Peterborough from whom it came to Lady ElizabethGermaine.H.W.14

This note is confirmed by records which show that Drayton, theNorthamptonshire estate of the Earls of Peterborough, did indeedpass in 1705 to Sir John Germain, who then bequeathed the estateto his second wife, the Lady Elizabeth (1680–1769) mentionedabove, in 1718 (Handley, 2008a). But does this provenance offer

ee’s work and their procurement of his manuscripts. Casaubon had already publishededit Dee’s work. For further biographical details, see Serjeantson (2004).nd manuscripts are mentioned at pp. 15, 86, 87 and 159.arters (2005) and British Library (2010).urator Frances Madden adds, ‘These Cakes of wax were transferred to the Department

ter for 1836–1839: ‘List of original Matrices of Seals and other articles transferred from

1).ish Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1966, 1001.1 (Part 1).

nd, states that: ‘Kelly was Dr Dee’s Associate and is mentioned with this very Stone inne.’ Another label, written by a different hand, helpfully provides us with the relevantng Glass, a stone;/Where playing with him at Bo-peep, He solv’d all problems ne’er so

S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549 543

any evidence for an association between this object and the workof Dee? Our strongest lead comes from the library catalogue ofthe second Earl of Peterborough, Henry Mordaunt (1623–1697)(Stater, 2004). Published in 1697, this document featured a numberof rare books on topics such as the occult, astrology and alchemy,thus providing a plausible explanation for the acquisition of Dee’s‘magical mirror’ (Tait, 1967, p. 210). Walpole himself first learnedof the mirror’s existence when he was asked by Lord Vere to assistwith the auction of Lady Germain’s possessions shortly after herdeath. Leafing through an old catalogue for the collection, Walpolefound an entry for ‘The Black Stone into which Dr Dee used to callhis spirits.’15

However, Lady Germain had either given away or sold the mir-ror before her death, so the mirror was nowhere to be found amongher effects. Luckily for Walpole, the object came into his possessionvia another route some years later. The mirror had been purchasedby the Duke of Argyll, who then bequeathed the object to his sonLord Frederick Campbell. When the Duke died in 1770, Lord Fred-erick requested Walpole’s assistance in the dispersal of his latefather’s effects, and seemingly sold or gave the mirror to his friend(Tait, 1967, pp. 208–211).

For Walpole, the mirror was a significant addition to the cabinetof curiosities at his neo-gothic home near the River Thames inTwickenham, Strawberry Hill. In an inventory of his possessions,Walpole describes the contents of this cabinet, a glass closet situ-ated within the Great North Bedchamber, including:

A speculum of kennel-coal, in a leathern case. It is curious forhaving been used to deceive the mob by Dr. Dee, the conjurer,in the reign of queen Elizabeth. It was in the collection of theMordaunts earls of Peterborough, in whose catalogue it is calledthe black stone into which Dr. Dee used to call his spirits. From theMordaunts it passed to lady Elizabeth Germaine, and from herto John last duke of Argyll, whose son, lord Frederic Campbell,gave it to Mr. Walpole. (Walpole, 2010, p. 501)

Unlike Henry Mordaunt, Walpole seems to have had little inter-est in the occult, astrology or magic and so the mirror does not ap-pear to have been displayed as an artefact of either of thesesubjects. Instead, the other objects in the closet seem to have beencollected either for their craftsmanship or their association withroyalty. For example, the inventory includes a significant numberof high quality decorative items, such as chinaware, snuff boxes,spoons and perfume bottles—as well as the spurs worn by KingWilliam III at the Battle of the Boyne and a pair of gloves wornby King James I. These artefacts served to demonstrate Walpole’swealth and prestige as a collector of fine objects with the socialconnections necessary to make such high status acquisitions.Within this context, Walpole’s purchase of the mirror serves a dualpurpose. On one hand it is a relic of John Dee, the Elizabethanmathematician and astrologer. On the other, it is a relic of QueenElizabeth I, who might have gazed upon or even touched the ob-ject, and hence on a par with the spurs and gloves of kings. Thissecond aspect may have had particular appeal to Walpole, whosekeen interest in the royal families of the sixteenth and seventeenthcenturies is demonstrated by the lavish paintings and busts of Tu-dor and Stuart Kings and Queens within the bedchamber (Snodin,2009, pp. 50–51).

In the description above, Walpole refers to the mirror as havingbeen carved from kennel-coal, a fine quality type of coal that can

15 Tait endeavoured to track down these catalogues shortly after the mirror was acquiredDepartment of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum, for the relevant correspondence.

16 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1966, 1001.1 (Part17 Letter from Adrian Digby to Rupert Bruce-Mitford, 28 September 1966. British Museu18 Object nos. Am 1907, 0608.2 and Am 1825, 1210.16.19 Sotheby’s Catalogue of the auction held on 4 May 1942, lot 92, p. 13, with the image

be fashioned into a smooth and polished surface. Yet in 1906, theKeeper of the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities atthe British Museum, O. M. Dalton, described the mirror as ‘a flatpiece of polished obsidian, evidently one of the mirrors used fortoilet purposes by the ancient Mexicans’ (Dalton, 1907, p. 383).When the mirror was finally acquired in 1966, X-ray diffractionanalysis confirmed that it was indeed made from obsidian, a blackform of volcanic glass.16 The connection with Mexico is intriguing,and it is tempting to speculate whether this provides a potential linkto Dee’s ownership of the object. Within Aztec culture, obsidian mir-rors were used by royalty as symbols of their power endowed by thegod Tezcatlipoca, ‘Lord of the smoking mirror’ (Olivier & López Lujàn,2009, p. 91). If this function was known at the time, then the use ofsuch mirrors for divinatory practices might have appealed to Dee,who may have acquired such a mirror during his studies at Louvainduring 1548–1550. At this time, King Charles V of Spain regularlyheld court in the region and it is possible that Dee might have ac-quired an obsidian mirror from a Spanish courtier returning withgifts from the New World (Tait, 1967, p. 205; French, 1972, p. 4).However, it is intriguing to note that an object of this shape or lo-cated with this historical context is not mentioned anywhere inDee’s writings. As we will see, the references in the manuscripts toa ‘stone’, ‘shew stone’ or ‘crystal ball’ employed during scrying ses-sions, accompanied by a sketch of that ‘stone’, apparently referexclusively to a spherical object, not a flat black, shiny stone witha handle. Thus at the present time, and without further evidence,any suggestion of a direct link between the obsidian mirror and JohnDee remains conjectural.

The Mexican origins of the obsidian mirror caused a few com-plications when the object was first acquired as it could be situatedwithin various historical narratives, as seen in this memo betweenthe Keepers of two Departments:

A question of delicacy arises over the Mexican mirror whichbelonged to Dr. Dee. If this should turn out to be genuine Ibelieve I am right in saying that technically it should belongto my department [Ethnography] . . .However, I do see thatthere is a case for retaining it in your department [British andMedieval Antiquities] if it was used as a divining object by Dr.Dee.17

Since the Department of Ethnography already had two obsidianmirrors in its collections,18 it was decided to allocate the new acqui-sition to the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities (nowthe Department of Prehistory and Europe).

4. The gold disc inscribed with the ‘vision of the four castles’

‘A unique relic of the most learned Englishman of his day’ ishow Sotheby’s summed up the importance of an object to be soldas lot 92 at auction on 4 May 1942 (reg. no. P&E 1942, 0506.1). Thedescription of ‘his [John Dee’s] gold disc’ in the catalogue, accom-panied by a photograph, states that the disc was inscribed with,

a diagram of the Vision of the Four Castles, which appeared tohis medium Edward Kelly, on the morning of June 20, 1584, ata house in St. Stephen’s Street, Cracow, where the two menwere staying.19

It claims that the disc was marked with the London date letter for1589. This is followed by a full length description of the diagram.

by the British Museum, but none could be found. See Object file 1966, 1001.1 (Part 1),

1).m, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1966, 1001.1 (Part 1).

on the preceding page.

Fig. 7. The ‘M’ mark on the reverse of the gold disc (reg. no. 1942,0506.1).�Trustees of the British Museum (image reference AN 970495001)

544 S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549

Within days of the British Museum acquiring the object,20 anincreasingly heated correspondence ensued between the curatorresponsible for the acquisition, Thomas Kendrick (1895–1979), a his-torian of Anglo-Saxon art and later Director of the British Museum(1950–59) (Wilson, 2005) and George H. Gabb (1868–1948), achemist, antiquarian and collector of scientific instruments (Oxford,Museum of the History of Science, 2011), who disputed the object’sassumed origin in the late sixteenth century, during Dee’s lifetime.21

Gabb’s main point of concern, namely the improbability of adate-letter standing on its own (Fig. 7), was confirmed by the new-ly formed Antique Plate Committee of the Goldsmith Company,that concluded in a letter sent by the Clerk, G. R. Hughes, on 8 July1942, that whilst it was possible that a maker’s mark could standon its own, it was extremely improbable for a date mark to doso.22 Kendrick did not refute this point—as he wrote in his letter toSir John Forsdyke, the Director of the British Museum, he thoughtthe letter to be a maker’s mark.23 He was nevertheless convincedof the disc’s age, as he felt that the script used on the disc was con-sistent with the Elizabethan period and that it even resembled Dee’sown hand24—a point strongly objected to by Gabb, who felt that theductus was later and in a style probably copied from Casaubon’s dia-gram or a later reproduction thereof.25

20 For £230 with support from the National Art Collections Fund, cf. the 39th Annual RepoDirector of the British Museum, Sir John Forsdyke, Kendrick states that the object had beeGurney family from Norfolk, but that the diagram had not been identified at that point, althto Dee, that had also been heralded shortly before the sale in an article by Charles R. BeardApril 1942), p.141 (see also note on p. 140), prompted considerable interest in the object afile 1942, 0506.1.

21 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1942, 0506.1. Thecontinue the correspondence further, on 21 August of the same year.

22 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1942, 0506.1. This obomission, although the statute [18 Eliz. c.15, enacted on 8th February 1575/6 that gold aCompany], only the maker’s mark is actually mentioned’, thus accounting for single mark

23 See note 20 above.24 Notes on these comparisons in the Object file 1942, 0506.1.25 These points are repeated over the course of the three months; see Object file 1942, 026 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object file 1942, 0605.1. Kend

called up; see letter dated 13 August 1942 sent by the librarian, Robin Flower.27 See Kendrick’s copious (alas, undated) notes in the Object file 1942, 0506.1, cf. his let

Intriguingly, the actual text of the diagram was never discussedin the many letters exchanged between Gabb and Kendrick in theperiod from 12 May to 21 August 1942. Yet Kendrick had gone toconsiderable trouble to ascertain the authenticity of the disc,including a careful examination of the text of the diagram in Dee’smanuscript—no easy task in the middle of the Second World War,when the manuscripts had been moved from Bloomsbury to Aber-ystwyth for protection against air raids.26 Kendrick noticed somedifferences between the diagram and the disc, but felt that thevariations in size between the disc and the manuscript (the formerhaving smaller quarters), the fringing of the arms and the differenceof orientation (the disc being ‘upside down’) resulted from the en-graver’s working methods, rather than the use of a different model.27

To come to a conclusion regarding the authenticity of the disc, itis necessary to return to Dee himself. Dee’s own written descrip-tion of the vision in his ‘Libri Septimi Apertorii Cracoviensis MysticiSabbatici’ records that it was revealed to his scryer, Edward Kelley,during the morning of Wednesday 20 June 1584 while the twomen were lodged in Krakow:

There appeared to him [E.K.] 4 very fayr castills, standing in the4 partes of the world: out of which he herd the sownd of aTrumpeter. Then semed out of every castill a cloth to be thrownon the grownd, of more than the bredth of a Table cloth.Out of that in the east, the cloth semed to be red, which wascast.Out of that in the sowth, the cloth semed white.Out of that in the west, the cloth semed grene, with great knopson it.Out of that in the north, spred or thrown out from the gateunder fote, the cloth semed to be very blak.Out of every gate then yssued one trumpeter, whose trumpetswere of strange form, wreathed, and growing bigger and biggertoward the ende.After the trumpeter followed 3 Ensigne bearers.After them 6 ancient men, with white . . .and stavs in theyrhands.Then followed a comly man, with very much apparel on hisback, his robe having a long trayn.After him came 5 men, carrying up of his trayn.Then followed one great Crosse, and about that 4 lesser Crosses.These Crosses had on them, each of them, ten, like men, theyrfaces distinctly appearing on the four parts of the Crosse, allover.After the Crosses followed 16 white Creatures.And after them, an infinite number semed to yssue, and to spredthemselves orderly in a cumpas, almost before the 4 foresaydCastills.Upon which vision declared unto me, I straight way set down aNote of it: trusting in God that it did signifye good.

rt (1942) of the NACF, London 1943, p. 12 no. 1273. In a note dated 22 July 1942 to then brought to the Museum twice before the sale by the then owners, members of theough the disc had been dated to the late sixteenth century. The newly established linkin Light—A Journal of Spiritualism: Psychical, Occult and Mystical Research, vol. LXII (30

nd increased the price. British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Object

first letter was written by Gabb on 12 May 1942, the last after Kendrick refused to

servation has recently been confirmed by Susan Hare, who showed that ‘by a curiousnd silver wares should be touched [i.e. marked] by the Wardens [of the Goldsmith

s found on plate from the Elizabethan period. Hare (1978, p. 16).

506.1.rick’s request for photographs was delayed considerably when the photographer was

ter to Forsdyke dated 22 July 1942 (see note 20 above).

S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549 545

(British Library, MS Cotton Appendix XLVI, Part I, fol. 188r)

Later that afternoon the vision is confirmed by the reappearanceof the angel Ave who claims to have been responsible for the morn-ing visit. He explains the symbolism of the components within thevision, and at Dee’s behest repeats the vision as follows:

The signe of the Love of God toward his faithfullFowre sumptuous and belligerent Castells, out of the whichsownded Trumpets thriseThe signe of Maiestie, the Cloth of passage, was cast forthIn the east, the Cloth red, after the new smitten bludIn the sowth, the cloth white, Lilly cullor.In the west a cloth, the skyns of many dragons, greene garlikbladedIn the north, the Cloth Heare cullored, Byllbery Juyce.The Trumpets sownd onceThe gates openThe 4 Castells are movedThere yssueth 4 Trumpetters: whose Trumpets are a pyramis,six cones, wreathedThere followeth out of every Castill 3, holding up the bannersdisplayed, with enseigne, the names of GodThere follow seniors six, alike from the 4 gatesAfter them cometh, from every part, a king, whose princis arefive, gardant, and holding up his trayneNext issueth the Cross of 4 Angles, of the Maiestie of Creation ingod, attended upon every one, with 4: a white Clowde, 4Crosses, bearing the Wittnesses of the covenant of god, withthe prince [superscript: 4 Kings] gon oute before: which wereconfirmed every one, with ten angels visible in cowntenanceAfter every cross, attendeth 16 Angels, dispositors of the will ofthose that govern the CastillsThey procede:And in, and abowt the middle of the cowrt, the Ensignes kepetheyr standings, opposite to the middle of the gate.The rest pause.The 24 senators mete.They seme to consult. (Ibid., fol. 193r)

The description of the vision is accompanied by a diagram con-sisting of a series of concentric rings bisected by four castles at thecardinal points.28 Each quadrant features a list of processionalcharacters:

Septentrio to OriensThe cloth blak as of bilbery juyce/A Trumpeter/Three Ensignebearers/Six Seniors/A King/Five Princes/5 Crosses/XVIdispositorsOriens to MeridiesThe cloth of passage for the King his Maiestie /Fresh red cullor/One Trumpeter/Three Ensignes/Six Seniors/The King/Five Prin-cis/5 Crosses in ye ayre/XVI DispositorsMeridies to OccidensThe cloth Lilly whyte/One Trumpeter/Three Ensigne bearerswith the 3 names of God in theyr ensigne/Six Seniors/TheKing/His five Princis/The Crosses . . . /XVI DispositorsOccidens to SeptentrioThe cloth dark grene cullor like garlik blades/One Trumpeter/Three Ensigne bearers/Six Seniors/The King/His five princis/The 5 crosses/XVI Disp. (Ibid.)

There are some minor difference between the description of thevision and the diagram. The ‘six ancient men’ have become ‘Six

28 Ibid., fol. 192v, originally a loose leaf that was pinned to the back of the blank fol. 1929 Casaubon (1659), pp. 168–171. The diagram is erroneously bound between pp. 72–7330 See note 20 above.

Seniors’ and the ‘comely man’ with a robe and train becomes‘The King.’ Similarly, the five crosses of different sizes simply be-come ‘5 crosses’, although there is a variation in size betweenthe five crosses engraved on the arms. The diagram otherwise cor-responds very closely with the descriptions of the vision on theprevious and subsequent pages of the manuscript—but is this thediagram that is inscribed on the gold disc?

Although at first glance the two diagrams may appear identical,on detailed inspection a number of differences become apparent.In the left column of Table 1 is a transcription of the diagram inthe manuscript, in the right, the readings from the disc (Figs. 8and 9).

Clearly, the texts within the quarters have become mixed up insuch a way that one almost wonders whether the layout of the dia-gram was copied upside down (i.e. with south at the top), whilstthe text within the quarters remained in the same position. Thus,the description associated with ‘Septentrio to Oriens’ in the manu-script has become linked to ‘Meridies to Occidens’ on the disc, thedescription for ‘Oriens to Meridies’ has made its way across to‘Occidens to Septentrio,’ and so forth. Additionally, there are cleardifferences in spelling (e.g. ‘collor’ on the disc instead of ‘cullor’ inthe manuscript) and in the capitalization of certain words (e.g. ‘TheCloth Blacke as of Bilbery juyce’ instead of ‘The cloth blak as of bil-bery juyce’ in the manuscript). Kendrick suggested that the engra-ver’s working style resulted in this ‘upside down’ appearance, butthis hardly explains the differences in spelling. Nor is it conceivablethat a customer would have accepted this result if the paper dia-gram was so clearly different. Is it not rather more likely that theengraver worked from a very similar, but somehow corruptedmodel (Fig. 10)?

The ductus of the diagram in Meric Casaubon’s transcription ofDee’s manuscripts, published in 1659 under the title ‘A true andfaithful relation of what passed for many years between Dr JohnDee and his spirits’,29 was mentioned by Gabb as a potential modelfor the disc. Kendrick carefully examined and noted these similari-ties, but came to the conclusion that, rather than copying his dia-gram from Dee’s manuscript, Casaubon had copied it from the golddisc, thus explaining the striking similarities between his diagramand the disc. But why would Casaubon have done so, when he other-wise transcribed from the manuscript? Dee’s diagram is still veryclearly legible today, and there is thus no reason to look for an alter-native model to copy from in the mid-seventeenth century.

What are we left with? There can now be little doubt that thedisc was not produced during Dee’s lifetime, nor was it made ata later date from the diagram in his manuscript. The engravingon the disc was faithfully based on the diagram in Casaubon’s(faulty) transcription of the ‘vision of the four castles.’ The stamped‘M’ may be either a maker’s mark, or an attempt to give the object’sprovenance credibility by adding what could easily have been mis-taken for a date-letter for 1589.

When was the disc produced? And what was its history beforethe sale at Sotheby’s? In the above mentioned note to the Directorof the British Museum, Kendrick states that prior to the sale thegold disc was brought to the Museum for opinion by members ofthe Gurney family,30 descendants of the banker and antiquarianHudson Gurney who died in 1864 in Keswick, near Norwich (Os-borne, 2004). At first glance there appears to be little obvious expla-nation for the ownership of this object by a banking family fromNorfolk. However, it is possible that there may be a link to an earlierNorwich resident, Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) (Robbins, 2008).A well known physician, Browne became close friends with ArthurDee (1579–1651), John Dee’s eldest son and sometime scryer, who

2v.but it should be in the region of pp. 168–171.

Table 1Comparison between the text found in the diagram of the Vision of the Four Castles in Dee’s manuscript and on the gold disc.

Dee’s diagram Gold disc diagramSeptentrio to Oriens Septentrio to OriensThe cloth blak as of bilbery juyce/A Trumpeter/Three Ensigne bearers/Six Seniors/A

King/Five Princes/5 Crosses/XVI dispositorsThe Cloth Lillywhite/One Trumpeter/Three Ensigne bearers wth ye/3 names of godin their Ensigne/Six Seniors/The King/his five Princes/The Crosses 5/XVIDispositors

Oriens to Meridies Oriens to MeridiesThe cloth of passage for the King his Maiestie /Fresh red cullor/One Trumpeter/

Three Ensignes/Six Seniors/The King/Five Princis/5 Crosses in ye ayre/XVIDispositors

The Cloth dark greene Collor like garlicke blades/One Trumpeter/Three EnsigneBearers/Six Seniors/The King/his five Princes/The 5 crosses/XVI Dispositors

Meridies to Occidens Meridies to OccidensThe cloth lilly whyte/One Trumpeter/Three Ensigne bearers with the 3 names of

God in theyr ensigne/Six Seniors/The King/His five Princis/The Crosses [. . .]/XVIDispositors

The Cloth Blacke as of Bilbery juyce/A Trumpeter/Three Ensigne bearers/SixSeniors/A King/Five Princes/five Crosses/XVI Dispositors

Occidens to Septentrio Occidens to SeptentrioThe cloth dark greene cullor like garlik blades/One Trumpeter/Three Ensigne

bearers/Six Seniors/The King/His five Princis/The 5 crosses/XVI Disp.The Cloth of passage for the King his Maiestie fresh Red collor/One Trumpeter/Three Ensignes/Six Seniors/The King/Five Princes/5 Crosses in ye are/XVIDispositors

546 S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549

moved to the city sometime during the late 1640s (Appleby, 2008).At the time of his Dee’s death, Arthur was continuing his father’sinterests, yet Dee appears to have entrusted his precious collectionof books and manuscripts to his friend and the executor of his will,John Pontois (Roberts, 2006). Arthur endeavoured to reclaim a num-ber of books and manuscripts in the decades after his father’s death,but many of the manuscripts were either impounded as State Papersor else destroyed during the Civil Wars (Deacon, 1968, p. 274). It isthrough this friendship that Browne acquired books and manuscriptsassociated with John Dee which he then passed on to his regular cor-respondent, Elias Ashmole (Robbins, 2008). However, without fur-ther evidence, any hypothetical link between the Norwichconnection and a gold disc, which is so evidently based on Casau-bon’s transcription of the vision, remains pure conjecture.

Nonetheless, we should note that both the gold disc and themarble copy of Dee’s ‘Holy Table’31 appear to be closely linked withCasaubon’s publication of Dee’s work in 1659. Although there is noevidence of a link between the two objects, the timing is indeedcurious.

5. The crystal ball or ‘shew stone’

In the popular imagination, the crystal ball is one of the essen-tial tools of a magus—and there are indeed a number of referencesto such an object in Dee’s manuscripts. In some instances thedescription of its use is accompanied by a small marginal sketchthat enables us to visualize the physical appearance of the crystalball. During a session on 22 December 1581 for example, Dee‘willed the skryer (named Saul) to loke into my great ChrystalineGlobe.’ Later during the same session, Dee refers to this object as‘the stone in the frame’ and a marginal sketch shows a ball in aring-mount topped by a cross, placed on what appears to be acushion or support of some kind (British Library, MS Sloane3188, fol. 8r) (Fig. 11).

On 10 March 1582, during a session with his scryer, Dee againrefers to ‘my stone in the frame’, accompanied by a sketch of a ballon the same cushion or support (ibid., fol. 9r). Finally, during a ses-sion on 13 January 1584, Edward Kelley claims ‘A voyce sayeth:Open the shew stone’ (British Library, MS Cotton Appendix XLVI,Part I, fol. 54v). The description of this session is accompanied bya sketch of a ball, again sitting on a cushion or support (ibid., fol.

31 See note 4, above.32 Illustrated London News, No. 416, 9 March 1850, xvi. 157.33 British Museum, Department of Prehistory and Europe, Register of Sir Hans Sloane—C34 Ibid., fol. 327r.

55v). Whether the ball is mounted or whether there is just a sec-ond line drawn around its circumference remains unclear.Although the description of the object twice lists a frame of somesort, the image in the margins depicts this only once. So whatdid the ‘shew stone’ look like? And has it survived?

There is indeed a crystal ball in the collection of the BritishMuseum (reg. no. P&E SLCups.232) that has been associated withJohn Dee since at least the mid-nineteenth century, when the fol-lowing note appeared in the Illustrated London News of 9 March1850, prompted by the recent sale of the effects of J. H. S. Pigott,of Brockley Hall in Somerset, that included the obsidian mirror:

In the British Museum is another relic of this same astrology, DrDee—his Magic Mirror—being a piece of rock crystal, of some-what smoky tint, fashioned into a globular form.32

Shortly thereafter, we find another reference to Dee’s crystal ballthat mentions it being on display in the Medieval Gallery:

Mediæval Collection. This Collection is generally arranged withregard to the material and workmanship of the objects . . .Case103. A crystal ball and wax cakes, used by Dr. Dee in his magicalexperiments. (British Museum, 1855, p. 262)

Intriguingly, there is no record of any provenance of this crystalball, although at some point in the past it became associated withone of three crystal objects mentioned in the registers of HansSloane’s collection. The first artefact is described as ‘a triangle cuttin chrystall glasse said to be used as a shew stone or conjuringinstrument’ in the Catalogue of Miscellanea, listed under the Miscel-lanies section as object number 1726.33 Unfortunately there is norecord of this triangular object in the Museum today. In the sameregister, listed under the heading Agate cups, bottles, spoons etc., ‘Alarge chrystale ball’ (object number 232) and ‘A small chrystalesphere or ball’ (object number 235) are listed amongst other objectsmade from agate or rock crystal; in this case without any referenceto ‘shew stones’ or ‘conjuring instruments.’34 Thus far, no clue hascome to light to explain why one of the two crystal balls listed in Slo-ane’s register came to be recorded as a relic of Dee, or, indeed,whether the ball on display in the Medieval Gallery was in factone of the two listed, or a different object altogether. Nonetheless,this view seems to have gone unchallenged from the 1850s onwards,

atalogue of Miscellanea, fol. 148r.

Fig. 8. Dee’s diagram of the Vision of the Four Castles (British Library, MS CottonAppendix XLVI Part I, fol. 192v). �The British Library Board (MS Cotton AppendixXLVI Part I)

Fig. 9. The gold disc with the engraving of the Vision of the Four Castles (reg. no.1942,0506.1). �Trustees of the British Museum (image reference AN968320001)

S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549 547

and at some point the crystal ball came to be referred to as no. 232.Why object 232 was chosen to represent Dee’s crystal ball ratherthan object 235 remains unclear.35

Today, this single crystal ball is displayed as one of the objectsassociated with John Dee. It should be noted, however, that otherinstitutions also claim to hold the very crystal ball employed byJohn Dee’s scryers. Furthermore, crystal balls in general are by nomeans rare. An object of this type, and with a Dee association,was stolen from the London Science Museum galleries in Decem-ber 2004, but recovered shortly thereafter.36 An interestingmounted crystal ball with unknown provenance is in the collectionof the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.37

6. The Dee objects in the British Museum today

Today, the objects associated with John Dee are on display inthe ‘Enlightenment Gallery’ (Fig. 12), a space formerly known as

35 The first reference to the sphere being labelled as SL.232 appears to occur in 1980, whenat the Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Florence, from 15 March to 15 June 1980 t

36 Object number A127915. For a report on the theft see Times (2004).37 Object number 51476. See Anon. (1997) for more details.38 Room 1, floor case 20.39 See Snodin & Roman (2009) for a complete overview of the exhibition and its catalog40 See McEwan & López Lujàn (2009) for a complete overview of the exhibition and its c

‘The King’s Library.’38 Created in 2003 to celebrate the 250th anni-versary of the founding of the Museum, the aim of this gallery wasto introduce visitors to the spirit of discovery, classification andincreasing specialisation in the ‘long 18th century’ (Sloan, 2003).

The mirror especially has been a popular item for loans to exhi-bitions in the United Kingdom and abroad, where it has functionedin various roles within different exhibition narratives. Recently, itwas sent to the exhibition Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, heldat the Yale Center for British Art (15 October 2009–3 January2010) and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (5 March2010–4 July 2010).39 Here, the mirror was used in the recreationof Walpole’s wide ranging collection, including the Great North Bed-chamber and his glass closet of chinaware and royal ‘souvenirs.’ Thelink with the Mexican origins was recently revisited in the BritishMuseum temporary exhibition Moctezuma: Aztec ruler (24 Septem-ber 2009–24 January 2010).40

7. Conclusion

In this paper we have reviewed the provenance of the BritishMuseum’s collection of Dee-associated objects by considering bothwritten sources and the nature of the objects themselves. The ob-jects with the strongest potential link to Dee are the three waxseals, since their dimensions and engraved surfaces correspondwell with Dee’s account of the instructions issued by the angelsUriel and Michael in March 1582. The appearance of the seals with-in the collections of the British Museum can be reasonably tracedthrough the collector Sir Robert Cotton, although further researchis required to resolve the finer details of this acquisition.

The fourth object that might have an authentic association withDee is the obsidian mirror. The previous ownership of the mirror iswell documented from its acquisition by Horace Walpole around1770 until its purchase by the museum in 1966. Our knowledgeof the mirror prior to 1770, however, is dependent upon circum-

in the preparation of the object going on loan to the 16th Council of Europe Exhibitionhe sphere is listed with this registration number.

ue.atalogue.

Fig. 10. Casaubon’s diagram of the Vision of the Four Castles in Casaubon (1659),between pp.72–73. �The British Library Board (Casaubon (1659) 719.m.12)

Fig. 12. The current display of the Dee-associated objects in the Enlightenmentgallery. �Trustees of the British Museum (image reference AN957711001)

Fig. 11. Dee’s sketch of ‘the stone in the frame’ (British Library, MS Sloane 3188, fol.8r). �The British Library Board (MS Sloane 3188)

548 S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549

stantial links with events in Dee’s life and later claims made byHorace Walpole. Thus, we still have to find a definite associationbetween the mirror and Dee himself.

Taking the gold disc as our fifth object, we have established thatthe engraving of the Vision of the Four Castles is based upon Casau-bon’s erroneous diagram of 1659, and can therefore state that thedisc certainly did not belong to Dee, nor was it made during hislifetime. Further research is clearly needed, but it is intriguing tonote that both the gold disc and the ‘Holy Table’ appear to be clo-sely linked with Casaubon’s publication of Dee’s work in 1659, andthat Casaubon worked in Cotton’s library which was associatedwith both the wax discs and the table.

Finally, we have also considered a crystal ball which appears tohave been associated with Dee since 1850. This is the most elusiveobject within our collection of Dee artefacts and has virtually nodocumentary evidence to support its description as Dee’s ‘shewstone’.

In addition to exploring the biographies of the objects associ-ated with John Dee, this study aims to highlight the role of materialculture in shaping Dee’s reputation. Since his collection of scientificinstruments has not survived (Dee, 1592, chap. 7), Dee’s reputationas a magician rather than as a Renaissance scholar has doubtlessbeen perpetuated by the existence and display of such ‘magical’

41 A study focusing on such instruments with the aim to readdress this balance is curre

objects at the British Museum and other institutions and their pop-ular association with Dee. The acquisition of the wax seals throughthe library of Sir Robert Cotton created a focal point for the collec-tion of magical items associated with Dee. As the collection anddisplay of objects grew to incorporate the crystal ball, gold discand obsidian mirror, Dee’s name became synonymous with magicamong public and academic audiences. The story might have beenvery different if Dee’s collection of scientific instruments hadsurvived instead.41

ntly in preparation.

S. Ackermann, L. Devoy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 539–549 549

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for theirhelpful comments and our colleagues in the British Museum fortheir support, especially Andrew Basham, Sue La Niece, SaulPeckham, Judy Rudoe and Dora Thornton. We are also grateful tothe staff at the British Library for their assistance with the Deemanuscripts and we would particularly like to thank JulianHarrison for his advice regarding the Cotton Library.

References

Anon. (1997). Sphere no. 5. Sphaera, 5. http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/sphaera/issue5/articl7.htm Accessed 24.01.11.

Appleby, J. H. (2008). Dee, Arthur (1579–1651). In Oxford dictionary of nationalbiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7415 Accessed 15.11.10.

Bennett, J. (1999). John Dee and his ‘‘Holy Table. The Ashmolean, 37(Christmas), 4–5.British Academy and Royal Historical Society Joint Committee on Anglo-Saxon

Charters. (2005). Kemble: Anglo-Saxon Charters. http://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/kemble/index.php?menuitem=11&pagename=-2 Accessed 6.12.10.

British Library. (2010). History of the Cotton Library. http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelprestype/manuscripts/cottonmss/cottonmss.html Accessed 1.09.10.

British Museum (1855). Synopsis of the contents of the British Museum (62nd ed.).London: British Museum.

British Museum. (2011). Collections Online Database. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database.aspx Accessed 27.01.11.

Casaubon, M. (1659). A true and faithful relation of what passed for many yearsbetween Dr John Dee and some spirits. London: Garthwait.

Clucas, S. (2006). Enthusiasm and ’damnable curiosity’: Meric Casaubon and JohnDee. In R. J. W. Evans, & A. Marr (Eds.), Curiosity and wonder from the renaissanceto the enlightenment (pp. 131–148). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Dalton, O. M. (1907). Wax discs used by Dr. Dee. Proceedings of the Society ofAntiquaries (Second Series), 21, 380–383.

Deacon, R. (1968). John Dee: Scientist, geographer, astrologer and secret agent toElizabeth I. London: Frederick Muller.

Dee, J. (1592). The compendious rehearsal of John Dee his dutifull declaration, andproofe of the course and race of his studious life . . .and of the very great injuries,damages, and indignities, which for these last nine years he hath in Englandsustained . . .made unto the two honourable commissioners, by her mostexcellent Majestie thereto assigned, etc. In T. Hearn (Ed.). Johannis, confratris& monachi glastoniensis, Chronica sive historia de rebus glastoniensibus (Vol. 2,pp. 497–551). Oxford: Sheldonian Theatre (First published 1726).

French, Peter J. (1972). John Dee: The world of an Elizabethan magus. London:Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Handley, S. (2008a). Germain, Sir John, first baronet (1650–1718). In Oxforddictionary of national biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10567 Accessed 8.12.10.

Handley, S. (2008b). Cotton, Sir Robert Bruce, first baronet (1571–1631). In Oxforddictionary of national biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/6425 Accessed 21.07.10.

Hare, S. (1978). Touching gold & silver: 500 years of hallmarks. Catalogue of theexhibition at Goldsmith’s Hall, London, 7–30 November 1978.

Heyworth, P. (2004). Wanley, Humfrey (1672–1726). In Oxford dictionary of nationalbiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28664 Accessed 12.01.11.

Huffman, W. H. (1988). Robert Fludd and the end of the Renaissance. London & NewYork: Routledge.

McEwan, C., & López Lujàn, L. (Eds.). (2009). Moctezuma: Aztec ruler. London: TheBritish Museum Press.

Langford, P. (2008). Walpole, Horatio, fourth earl of Orford (1717–1797). In Oxforddictionary of national biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28596 Accessed 26.01.11.

Museum of the History of Science Oxford. (2011). Summary of manuscripts held inthe collections, including the papers of George H. Gabb (1868–1948). http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/library/manuscript-summary Accessed 25.01.11.

Sloan, K. (Ed.). (2003). Enlightenment: Discovering the world in the eighteenth century.London: The British Museum Press.

Olivier, G., & López Lujàn, L. (2009). Images of Moctezuma and his symbols ofpower. In C. McEwan, & L. López Lujàn (Eds.), Moctezuma: Aztec ruler(pp. 78–123). London: The British Museum Press.

Osborne, P. (2004). Gurney, Hudson (1775–1864). In Oxford dictionary of nationalbiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11765 Accessed 3.11.10.

Robbins, R. H. (2008). Browne, Sir Thomas (1605–1682). In Oxford dictionary ofnational biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/3702 Accessed 3.11.10.

Roberts, J. R. (2006). Dee, John (1527–1609). In Oxford dictionary of nationalbiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7418 Accessed 5.07.10.

Serjeantson, R. W. (2004). Casaubon, (Florence Estienne) Meric (1599-1671). InOxford dictionary of national biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4852 Accessed 19.04.11.

Smith, T. (1696). Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum Bibliothecae Cottonianae.Oxford: Sheldonian Theatre.

Smith, T., & Tite, C. G. C. (1984). Catalogue of the manuscripts in the Cottonian Library,1696. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer.

Snodin, M. (2009). Going to Strawberry Hill. In M. Snodin (Ed.), Horace Walpole’sStrawberry Hill. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Snodin, M., & Roman, C. (Eds.). (2009). Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill. New Haven& London: Yale University Press.

Speck, W. A. (2007). Harley, Robert, first earl of Oxford and Mortimer (1661–1724).In Oxford dictionary of national biography Oxford: Oxford University Press.http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12344 Accessed 25.01.11.

Stater, V. (2004). Mordaunt, Henry, second earl of Peterborough (bap. 1623, d.1697).In Oxford dictionary of national biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/19163 Accessed 22.11.10.

Tait, H. (1967). ‘The devil’s looking glass’: The magical speculum of Dr John Dee. InW. Hunting Smith (Ed.), Horace Walpole: Writer, politician, and connoisseur. NewHaven: Yale University Press (pp. 195–212, Appendix II pp. 337–338).

Times. (2004). Report on the theft of the Dee crystal ball, 11 Dec. 2004, onlineversion. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article401766.ece Accessed24.01.11.

Tite, C. (1994). The manuscript library of Sir Robert Cotton. The Panizzi lectures 1993.London: British Library.

Walpole, H. (2010). A description of the villa at Strawberry-Hill. London: PallasAthene.

Wilson, D. M. (2005). Kendrick, Sir Thomas Downing (1895–1979). In Oxforddictionary of national biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31303 Accessed 25.01.11.