Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

-

Upload

mariagallagher -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 1/11

The Bartók of the QuartetsAuthor(s): Gerald AbrahamReviewed work(s):Source: Music & Letters, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Oct., 1945), pp. 185-194Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/728029 .

Accessed: 14/03/2012 12:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music &

Letters.

http://www.jstor.org

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 2/11

JMusic a n d LettersOCTOBER 1945

Volume XXVI No. 4

THE BARTOK OF THE QUARTETSBY GERALD ABRAHAM

WRITNG some time ago in "another place " on Bart6k's sixth stringQuartet, I remarked that it was " the latest of what is arguably the most

important series of string quartets since Beethoven ". I promptlyqualified that apparently extravagant claim by pointing out that

there have not been many " series " of quartets since Beethoven at all; so manymusicians-Franck, Debussy, Ravel, Elgar, Sibelius, for instance-have thrown off

single quartets of great value and then failed to return to the medium. Brahms's

three quartets and Schumann's set of three, again, hardly represent their composersat the height of their powers; one certainly cannot trace in them their composer'smusical autobiographies. It is rare indeed to find, as we do in Bart6k, a composerwho has turned to the string quartet at every stage of his creative career and putinto his quartets the very best of himself.

Bart6k is said to have written his earliest string quartet in I899,but thiswork, like most of his early compositions, has never been published.The published quartets are dated as follows:

No. I (Op. 7) 1908No. 2 (Op. 17) 1915-17No. 3 (without opus-number) September 1927No. 4 (,, ) July-September 1928No. (5 ,, ,, ) August 6th-September 6th 1934No. 6( ,, ,, ) August-November I939

and thus give a fairly complete cross-section of Bart6k's development.Edwin von der Niill has traced that development, up to the first pianoConcerto,l through the piano music; but although the piano compo-sitions are much more numerous, they are marked by such vagariesof style-many being folksong arrangements or pieces for children-that they do not collectively give such a clear impression as the six

quartets. Moreover the quartets represent Bart6k's best or at any ratemost serious work at each period-which can hardly be said of manyof the piano pieces. The Bart6k revealed by the quartets (we may putit) is the greater part of Bart6k, though by no means the whole Bart6k.

The earliest work in which Bart6k showed his real mettle was the setof fourteen ' Bagatelles ' for piano, Op. 6. The ' Bagatelles ' might servealmost as a dictionary of modern music; each is a study in one or moreof the devices that were just being added to the musician's vocabulary:

1. BWlaBart6k (Halle, 1930).

Vol. XXVI. 185

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 3/11

i86 MUSIC AND LETTERS

polytonality, added-note chords, fourth-chords and melodies derivedfrom them, appoggiaturas used instead of" real " notes of the harmony,and so on. There are some charming things among the ' Bagatelles,'but a good many dry things. One gets the impression that some of themare rather cold-blooded, cerebral experiments; indeed Bart6k himselfadmitted as much to von der Nill. As a set they are much less immedi-ately attractive than the 'Ten Easy Piano Pieces' written in the sameyear: I908. The first string Quartet also dates from I908, and bearsthe opus-number following that of the ' Bagatelles'; it also bears tracesof the same delight in new-found resources. But it has none of the nakedexperimentalism of the 'Bagatelles'; it is live music. It is essentially,perhaps, not so very different from the earlier Bart6k, though the thoughtis now expressed in more difficult idioms. The middle section of the slowfirst

movement,for instance:

molto appassionato, rubato

Lento (J =50) : :(Viola) MP

Ex. -t1 -,J . etc.

(cello) r-

is of the early, not the mature Bart6k. And the expressive canon, firstfor the violins, then for viola and cello (with the violins continuing in

free parts), which opens the rovement and, in a curtailed form, closesit, has really very little in common with Bart6k'slater uncompromisinglylinear style; the chromatic polyphony should be no more, if no less,worrying to modern ears than the polyphony of the Prelude to Act IIIof' Parsifal' was to Victorian ears, and it analyses out, harmonically,in something the same way. Nor does the allegretto econd movement,which follows without a break, offer any special difficulty; the thirdsin which the transition-theme is stated are curiously un-Bart6kian. (Icall it the transition-theme because it is so used, although it is laterwoven firmly into the movement proper).

There is a break after this second movement, and with the intro-duction to the third we at last reach music that bears the quite unmistak-able hall-mark of Bart6k: " stamping" chords for the three upperstrings, the only outlet for his tendency to percussivenessthat he had yetfound through this medium, and the rhapsodic cello recitative thatanswersthem. Two points in particular attract attention in the recitative:the J J. rhythmic figure, from Hungarian folksong, and a motive

obviously derived from an accompaniment figure that has played an

important part in the allegretto:

(a) Allegretto (J. 46)

Ex.-2 I -rF c.r

p semplice

(K) (J 120o) _-.'_ ~ .-z- .'' . .

j poco agitato

But it is only with the opening of the finale proper that the importanceof this motive becomes fully manifest:

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 4/11

THE BARTOK OF THE QUARTETS I87

Ex.J I-I

^.av7 r $ t o t r ,jurr(Via, Cello unis.) bI b

'I

, ,resc., ,

(The chafing seconds of the violin parts are, of course, very characteristicof Bart6k; but their uncharacteristic resolution suggests that the move-

ment dates from before the piano'

Bagatelles.') Ex. 3turns

outto

bethe first subject of a movement conceived broadly on the lines of sonataform. However bold his melodic, rhythmic and harmonic experiments,Bart6k has seldom revealed revolutionary viewg of form, though thethird Quartet is boldly experimental; indeed he has often appeareddefinitely conservative in this respect. In this movement the formaloutline is easily recognizable depite the organic fusion of sections and theblurring of tonality and cadences. The key is A minor-a very Bart6kianA minor, of course-and the exposition consists mostly of development(the motive a, worked imitationally, b more lyrically); a second subjectduly turns up, adagio, n what Bart6k probably regarded as B flat minor;

and there is a development " proper ", beginning with a declamatoryoctave passage and proceeding by way of a lengthy fugato on a themeevolved from Ex. 3. The evolving process includes the growth of a newmotive with a triplet kink, which plays some part in the recapitulation,but the recapitulation is no freer than many classical examples, and theadagiosecond subject even recurs in the tonic. Bart6k was still clingingto shreds of the tonal principle when he wrote his first Quartet.

In the interval between this and the second Quartet he wrote, amongother things, the 'Dirges' for piano, 'Bluebeard's Castle', the 'DeuxImages' and 'Four Pieces', Op. 12, for orchestra, and 'The WoodcutPrince', works in which he showed himself a complete master of the

new resources that had been only partly assimilated in I908. Thesecond Quartet is thoroughly characteristic in a way that the first,as a whole, is riot. It is by no means as difficult to grasp as the nexttwo quartets of ten years or so later; but, standing back from the quartetsas a series and trying to consider them in perspective, one feels thatperhaps Nos. 3 and 4 are in one sense only complications and subtili-zations of an essence that is already fully present in No. 2. The simplicityand intimacy of No. 2, as compared with No. I, are very noticeable,and the chief second-subject theme of the first movement is remarkablefor its euphony (admittedly a rare quality in Bart6k), particularly whenit returns in the

recapitulation:() 132

Violins

Celloor -

'pp L L

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 5/11

MUSIC AND LETTERS

2. 1- \ii i

For the first movement of No. 2, like the finale of No. I, is in sonataform, and the two movements have this further point in common thatone of the transition themes here has precisely the same triplet " kink"

that we noticed in the earlierwork. To speakof" themes "in the ordinarysense, however, becomes a little misleading in dealing with music of this

type. There are motives of four or five notes, and there are thoughtsspread over many bars; but the motives by no means constititute.thetrue substance of the thoughts: they are not so much the bricks in themusical structure as the mortar. The subtlety,with which motive growsfrom motive, and with which a motive gradually assumes a new form,is well worth close study (there are strikingparallels to Sibelius'smethods),but could be shown here only with the help of abundant music-typeexamples. However, two shorter examples must be used to illustrateone other characteristic of Bart6k's handling of sonata form: his con-

ception of reprise. In his recapitulations themes are liable to returnin strongly modified forms; as a rule in simpler or at any rate more

easily apprehended forms and in a purer harmonic atmosphere. I

quote the opening of this movement and the parallel passage, the openingof the recapitulation:

M)oderato (J 18-60) , - _

Violins t - I ) L

Ex. 6 secwpetenuto

&elloW.F_

pIL

:Ltl>r-r.._.,

Tempo I, ma sempre molto tranquille

I<(}130) / .Zpo'ce

p ten_to . etc.

I.1ar'O'Fr Isr,

x88

I

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 6/11

THE BARTOK OF THE QUARTETS

Both the scherzo and the lentofinale present peculiar puzzles andattractions. The puzzle of the scherzo is its form, which appears at first

hearingor

readingto be hardly existent-or at any rate to be conditioned

simply by the heading, Allegromoltocapriciososic), and held together bynothing more than its persistent minor-third motive. But if it be con-sidered as a suite of miniature dances connected by lyrical interludes,on exactly the same lines as the much more extended 'Dance Suite'for orchestra (written in 1923), everything becomes clear. Like the dancesthat make up this later Suite, those of the middle movement of the

Quartet are attractive and strongly rhythmical; not (I should say)actual folk dances or imitations of them, but impregnated, like the vastbulk of Bart6k's music, with influences from Magyar folk music. The

gradual-and to the unaided ear quite imperceptible-transition from

the 2-4 of the sostenutonterlude to the 3-4 of the allegromoltodance is

typical of Bart6k'splastic conception of rhythm and tempo.The final lentois harder -to accept. Its painful brooding tries the

ear's patience much more than the lively clashes of the middle movement.Bart6k seems here to be experimenting a little too self-consciously withhis fourths-harmony; near the end he builds up a chord of five perfectfourths (A$, DS, G$, C#, F#, B). But the muted passage, lentoassai,is a beautiful demonstration of the expressive possibilitiesof this generallyrather hard and unyielding harmonic idiom:

Lento assai(J 52)

Violins 4 J I j JI. J

Ex.6 r F r -py cn sord.

tViola J oI.& Cello

IAif J FI

sprss.olto*i jt'J I-h", , tj ftj

r f- -^ff^?- r<r ^molto

This is Schoenbergian; but comparison with, say, the opening of thesecond of Schoenberg's ' Fiinf Orchesterstucke':

Moderato crotchets

Solo :.ello- " .

will at once show Bart6k's superior expressive power.

189

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 7/11

MUSIC AND LETTERS

The finale of Op. 7 is to me the only really " difficult" movementof the first two quartets, but in Nos. 3 and 4 the difficulties thicken. No. 3is a particularly hard nut to crack; it came as the climax to a whole

series of " difficult " works including the two violin Sonatas, the pianoSonata and the first piano Concerto. To the customary harmonic diffi-culties of Bart6k's music and the difficulty of a melodic idiom of whichone parent is a particularly remote folk music, the other intellectualmodernism, are added special difficulties of structure: of both inner,detailed structure and outer, general structure. Bart6k's motive-logicis nowhere tighter than in the third Quartet, but it is also nowhere more

elliptical than in its primaparte. To grasp all the links in the chain ofmusical reasoning is impossible to the unaided ear, difficult to the score-

reading eye. Yet one feels with absolute conviction that this is notmere

paper music,like so much of

Schoenberg;the

ingenuitiesof motive-

logic constitute the structural principle, the organic tissue, of the music-not its real sense. That has to be apprehended in longer periods. One

may put it that Bart6k's third Quartet occupies the same place in hiswhole work as Sibelius's fourth Symphony in his. The gradual growthof one motive-form into another, the constructive functions of certainintervals (particularly the perfect fourth), and on the other hand thealteration of intervals to provide new melodip forms: all demand bar-

by-bar study. But, short of critical exegesis on that scale, one canstill point out the best ways of penetrating to the heart of the music.For Bart6k is consistent in his personal development; one can generally

find clues to his new works in his earlier music; he even opens this" difficult " third Quartet, after the five introductory bars, with a canonfor the violins-a very Bart6kian canon with inessential notes:

Moderato (J =88)

1 r .VZ17 < h ..L=-| etc.

precisely as he had opened the first Quartet with a canon for the violins.

And, as I have said, Bart6k's themes are liable to return, in recapitu-lations, in more easily apprehended forms and in a purer harmonic

atmosphere. So we shall do well to look for the thematic clue to the

Quartet on some later page. And accordingly we shall find it, not inthe part of the Quartet actually marked ricapitulazioneellaprimaparte,but towards the end of the primaparteitself:

I9o

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 8/11

THE BART6K OF THE QUARTETS 191

_(J s 84)Ex.9 iy 1,

$r wmi r ff IL4[p p

m,u?o /iP sh.

That passage, played by second violin and viola in octaves, containsthe thematic

germof the whole movement.

But in this Quartet it is perhaps wrong to speak of " movements ".It plays without a break and, like so many older and newer experimentsin single-movement cyclic form (Sibelius's seventh Symphony is one ofthe few exceptions), fails to convince one that it is wholly successful.In the later quartets Bart6k returned to a more normal plan. But herehe gives us a primaparte,an exposition of the hard sayings just discussed,followed by a seconda artewhich is best described as incessant variationson a seven-bar theme of folk-dance character:

Allegro (J t20)

Ex.to

puzz.P

The variations, all very typical of Bart6k's method of moulding hismaterial plastically, grow very naturally, each from its predecessor,and-with all their use of transformation and inversion, canon and

fugue-are easy to follow. But having towards the end reminded usin a menomosso,martellato assage of a point in the first movement, theybreak into what the composer calls a ricapitulazione ella prima parte.

Needless to say, it is a recapitulation only in the Pickwickian sense, notonly much condensed but with the material altered generally beyondaural recognition. And the work ends with a coda that is essentiallya brilliant and exuberant continuation of the seconda arte.

The third Quartet is " on ", but not " in ", C#. That is to say,there is no trace of major or minor tonality and C# cannot be called a

tonic, but the note C$ acts as a centre of gravity, an artificial tonic.

Similarly the fourth Quartet is " on " C and the fifth " on " Bb. Writtenat an interval of six years, with the second piano Concerto half-waybetween them, they represent successive stages of descent from the

asperity of No. 3. Each is in five movements, of which the first and fifth,

and second and fourth, in each case balance each other:

No. 4 No. 5Allegro Allegro

Prestissimo AdagiomoltoJon troppoento Scherzo alla bulgarese)

Allegretto izzicato AndanteAllegromolto Finale(presto)

In both Quartets the first movements are in easily recognizable sonataform, though in No. 4 some of the material, and in No. 5 all the material,

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 9/11

MUSIC AND LETTERS

is inverted in the recapitulation. And in No. 5 the second subject returnsbefore the first (for which, of course, there are precedents in the nine-teenth-century romantics), so that not only the whole Quartet but alsoits first movement is in this " arch " form, A B C B A, which may wellhave been suggested to Bart6kby Alfred Lorenz's monumental' Geheim-nis der Form bei Richard Wagner ', of which the first volume waspublished in 1924 and which has much to say about Bogenform.I shouldexplain that the first and fifth, and second and fourth, movementscorrespond to some extent in substance as well as in general tempo.The finale of No. 4 is based on material from the firstmovement, and theendings of both movements are practically identical. Again, as Alexander

Jemnitz was the first to point out,2 the rondo-finale of No. 5 is based on afree inversion of the chief theme of the first movement; while the two

slow movementsare

not only linked by common motive-particles,both have the same expressive melody as their central feature-thoughthe adagiomelody:

(J40)

Ex.iit4iA -. Ie

.-tc,

p Un poco espress.

is naturally varied in the andante:

(J o0)

Ex.i2

~ I:." -i i

P spr- .?

; t4f1

7 1 etc.

The central alla bulgarese,again, is cast in the classical scherzo-trio-scherzo pattern, the scherzo material being inverted the second time.

As sheer sound that shimmering alla bulgaresewhich repays compari-son with the last six pieces, the Bulgarian dances, of' Mikrokosmos')is delicious. Indeed the whole of the fifth Quartet is less trying to theunaccustomed ear than the fourth, much less than the third. The twoslow movements are easily appreciable; so too is the rondo-finale withits odd grimace in A major, conindijferenzand meccanico,ust before the

coda, though I personally find less in it than in the powerful dancingfinale of No. 4. The opening theme of the first movement representsa remarkable adaptation of Bart6k's innate percussive tendency to the

quartet medium:

(J 38ts-182)unis.

Violins

Ex. t3 j

Viola uJ J tJIjJ AJLLL T& Celloo .

2* His long and detailed study of the fifth Quartet in 'Musica Viva (April 1936) is the only reallythorough and satisfactoryanalysisof a Bart6kquartet I have ever come across.

192

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 10/11

THE BARTOK OF THE QUARTETS

X=*-s{-F--rnn

.

Once more a canonic exposition! (Though my quotation is necessarilytoo short to show more than the beginning of the long-breathed canon.)Very characteristic of Bart6k'smotive-technique is the way the quintuplet"kink " inserted in the viola-cello line in bars 8, 0oand II:

Ex.4

is beheaded and given a new tail to become the coda theme:

(J - 88)Ex.15 1Tl

Its shadow, cancrizans(x),had already fallen across the second subject:

Meno mosso (J =z2- 108).__strjI x I

ExA.168 4 1

p dotce

Or is that too fanciful? But such thematic subtleties are intenselycharacteristic of Bart6k. He moulds and remoulds his motive-particles,resolving one shape into another until it is quite impossible to determine

whether such subtleties are deliberate or accidental. But (it cannotbe too often repeated) this motive technique is simply a device for formingmusical tissue, a means to an end, not the end itself. It must be admitted,however, that in beauty of sound the central movement of No. 4-lackingthese subtleties, but with sonorous long-held and repeated chords,against which the cello sings a very Hungarian rhapsody-and the twoslow movements of No. 5 surpass the much more finely woven quickmovements of either quartet. Amateurs often approach Beethoven, too,most easily through his slow movements.

From the third Quartet onward Bart6k began to experiment withnew sound-effects. In No. 3, in addition to all the

customarycolour-

devices of ponticello nd so on, including passages col legno,he introduceslong glissandion all four instruments simultaneously and double-stopsglissando; in the coda he employs quadruple stopping on the cello,played downward or down-and-up. In No. 4 he not only gives this newup-and-down arpeggio effect to the other instrumentsas well, but experi-ments with a new type of percussive pizzicato: "a strong pizzicatomaking the string rebound off the fingerboard ". The latter is usedagain, though for one note only, at the end of the scherzo of No. 5;and in the adagio of No. 5 the second violin, accompanying Ex. Ii,is asked to play four notes " pizzicato with the nail of the first finger of

I93

8/2/2019 Abraham - The Bartók of the Quartets

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/abraham-the-bartok-of-the-quartets 11/11

MUSIC AND LETTERS

the left hand, at the extreme end of the string ". But I must emphasizethat all these " tricks" are used very sparingly.

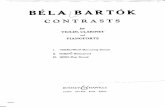

They are used again, though very little, in the sixth Quartet-separated from the fifth by a group of works that includes the Sonatafor two pianos and percussion, the ' Music for Strings, Percussion andCelesta' and the violin Concerto. Like the Concerto, the sixth Quartetrepresentsyet a furtherstage in Bart6k'sprogresstoward classic simplicity.Texture, form, rhythm: all are crystal-clear, especially in the two" outside " movements. Nearest to the earlier Bart6k are the secondand thirdmovements: a march (akin, but farsuperior,to the' Verbunkos 'first of the three ' Contrasts' for violin, clarinet and piano written theyear before) and a ' Burletta'. For in No. 6 the composer abandonsthe five-movement " arch " of its two predecessorsand tackles the prob-lem of over-all formal

unityin a new

way,or rather

bya new

applicationof that favourite nineteenth-century device, the motto theme. Themotto here is the mournful, Magyar-folksongish strain played by theviola unaccompanied at the very beginning. Played by the celIo againsta shimmering, muted background, it also introduces the march; worked

polyphonically, it provides the prelude to the ' Burletta '. But in noneof these three movements does it play any but a preludial part. It is anidee ixe three times shaken off. In the short, sad finale it returns andrefuses to be shaken off. It dominates the whole movement, and thoughtwo of the main themes of the first movement proper make a transitoryappearance-the usual Bart6kian link between first and last movements

-they are now heard in slow tempo, subdued to the mood of the mottotheme. And with the first part of the motto, again on the viola, in its

original form and at the original pitch, the Quartet ends in a mood of

profound and mournful resignation which may have been inspired bycontemporary events. (The score, it will be remembered, is dated

"August-November I939.")Most of the familiar characteristics of Bart6k's technical procedure

reappear in the sixth Quartet, e.g. when the march proper is repeatedafter the trio, some of the material returns in free inversion. But every-thing sounds clearer, easier, less aggressively individual. The firstmovement is in absolutely classical sonata formwith a return to something

very like tonality: a first subject in D minor-major and a second subjectin a contrasted key in the exposition, in a reconciled key in the recapitu-lation. And there is more than one point where one is reminded ofBeethoven's last quartets: at the beginning, for instance, directly afterthe viola motto, all four instruments in pesanteoctaves announce the realfirst subject of the movement in rhythmic augmentation-a passageprecisely parallel to the opening of the ' Grosse Fuge '-while the maintheme of the march awakens echoes of the alla marcian Op. 132. Suchsimilaritiesare only superficial,musically of no importance. Yet somehow

they do not seem insignificant. It is not insignificant that one can mentionBeethoven's last

quartetsand Bart6k's in the same sentence without

appearing ridiculous.

194