ABLE OF CONTENTSarchived.parapsych.org/PDF/1998_PA_proc_pt1.pdf · 2016. 6. 5. · Proceedings of...

Transcript of ABLE OF CONTENTSarchived.parapsych.org/PDF/1998_PA_proc_pt1.pdf · 2016. 6. 5. · Proceedings of...

-

Proceedings of Presented Papers 1

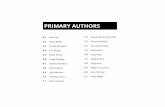

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Authors(s)

Paper Page:

Alexander, Persinger, Roll, & Webster

EEG and SPECT data of a selected subject during psi tasks: The discovery of a neurophysiological correlate

3

Alvarado & Zingrone A Study of the Features of Out-of-Body Experiences in Relation to Sylvan Muldoon’s Claims

14

Delanoy & Morris A DMILS Study with Experimenter Trainees

22

Houtkooper, Schienle, Stark, & Vaitl

Atmospheric electromagnetism: The possible disturbing influence of natural sferics on ESP

36

Krippner, Wickramasekera, & Wickramasekera

Working with Ramtha: Is it a “High Risk” Procedure?

50

McDonough, Warren, & Don Third Replication of Event-Related Brain Potential (ERP) Indicators of Unconscious Psi

64

May & Spottiswoode The Correlation of the Gradient of Shannon Entropy and Anomalous Cognition: Towards an AC Sensory System

76

Mulacz Eleonore Zugun – The re-evaluation of an historic RSPK case

94

Nichols & Roll The Jacksonville water poltergeist: Electromagnetic and neuropsychological aspects

97

Palmer Correlates of ESP magnitude and direction in the FRNM manual Ganzfeld database

108

Palmer ESP and REG PK with Sean Harribance: Three new studies

124

-

2 The Parapsychological Association Conference

Parker and Westerlund Current Research in Giving the Ganzfeld an Old and a New Twist

135

Radin, Machado, & Zangari Effects of distant```` healing intention through time and space: Two exploratory studies

143

Radin Further investigation of unconscious differential anticipatory responses to future emotions

162

Roll & Persinger Poltergeist and nonlocality: Energetic aspects of RSPK

184

Roll & Persinger Is ESP a form of perception? Contributions from a study of Sean Harribance

199

Sherwood Relationship between the hypnagogic/hypnopompic states and reports of anomalous experience

210

Sherwood, Dalton, Steinkamp, & Watt

Dream GESP study II using dynamic video-clips: investigation of consensus voting judging procedures and target emotionality

226

Sicher, Targ, Moore, & Smith

Positive therapeutic effect of distant healing in an advanced AIDS population

242

Steinkamp A guide to independent coding in meta-analysis

243

Steinkamp & Milton A meta-analysis of forced-choice experiments comparing clairvoyance and precognition

260

Wackermann Characterization of states of consciousness based on global descriptors of brain electrical dynamics

276

-

EEG and SPECT data

Proceedings of Presented Papers 3

EEG AND SPECT DATA OF A SELECTED SUBJECT DURING PSI TASKS: THE DISCOVERY OF A NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL

CORRELATE1

Cheryl H. Alexander Institute for Parapsychology, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Michael A. Persinger Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada

William G. Roll State University of West Georgia, Carrollton, Georgia, USA

David L. Webster Sudbury General Hospital, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada

ABSTRACT

Electroencephalograph (EEG) and Single-Photon Emission Computerized Tomography (SPECT) data were collected from Sean Harribance, a well documented psychic who has previously participated in laboratory research, while he was engaged in psi tasks. This data was independently collected from two different laboratories during 1997. The primary goal of the EEG data collection was to determine the dominant electrocortical activity and its location while Sean participated in psi tasks. EEG data were collected from Sean in the following five psi tasks: two psychic readings from photographs, two runs of card guessing with standard ESP cards using the down through method, and one remote viewing trial. After removing any artifacts, the data for each condition were then spectrally averaged and topographic brain maps were computed which showed that while Sean was engaged in psi tasks, alpha was dominant bilaterally in the paraoccipital region, with alpha power being strongest in the right parietal lobe at electrode placement P4. A lack of alpha activity was seen in the frontal and temporal lobes. For subsequent data analysis, Dr. Robert Thatcher at Applied Neuroscience Laboratory in Redington Shores, Florida edited and removed any artifacts from the raw EEG data collected from Sean during an eyes-closed baseline. He then analyzed the data for EEG coherence, phase, amplitude differences, and relative power, and compared these measures to the data in his Lifespan Reference EEG Data Base using the appropriate age-matched group. Results show deviations from the reference data base that are primarily bilateral, involving the occipital, temporal, and frontal regions. Sub-optimal neural function is indicated, especially in the frontal and temporal cortical regions.

1 The research in Canada was supported in part by the Sean Harribance Institute for Parapsychology Research

(SHIPR), Houston, Texas. Transportation to Canada for Cheryl Alexander was provided by the Laboratories for Fundamental Research.

-

Alexander et al.

4 The Parapsychological Association Conference

Two Tc-99m SPECT ECD brain scans were completed with Sean in order to contrast a baseline resting condition with a psi task condition. The results indicate the areas of Sean’s brain that were active while he was in the psi task condition and the baseline resting condition. The most pronounced finding was increased uptake of the tracer, relative to cerebellar uptake, in the paracentral lobule and in the superior parietal lobule of the right hemisphere only during the psi task condition. A mild decrease of function in the frontal, temporal, and thalamus regions is suggested by the lack of uptake of tracer in these areas during both conditions. The consistency of the results across laboratories, equipment, experimenters, and research protocols suggests the existence of a neurophysiological correlate which is stable across both time and conditions. It is hypothesized that the parietal cortex is activated while Sean is engaged in psi tasks as this part of the brain is attributed with visual search attention via the posterior attention network. Also, it is speculated that Sean’s brain may be more highly developed or may function at a higher level in the parietal cortex to compensate for a lack of activity or sub-optimal neural function in the frontal and temporal cortical regions. The data presented is specific for Sean and may not be applicable to others. Future research with other selected subjects is needed in order to determine if these results can be replicated between subjects.

INTRODUCTION

Examining the psychophysiological correlates of psi performance by using the electroencephalograph (EEG) to monitor brain waves is not a new concept in parapsychology. From the 1950s to the 1970s, several studies (Wallwork, 1952; American Society for Psychical Research, 1959; Cadoret, 1964; Morris & Cohen, 1969; Honorton, 1969; Stanford & Lovin, 1970; Honorton & Carbone, 1971; Honorton, Davidson, & Bindler, 1971; Morris, Roll, Klein, & Wheeler, 1972) were conducted exploring a possible relationship between alpha abundance and the proportion of correct guesses on an ESP task. The EEG results of these studies are contradictory, perhaps because of varying procedures, methods of data analysis, subject selection, etc. The most consistent finding within these studies, however, was a positive correlation between alpha abundance and high ESP scores, especially for subjects preselected for expertise at the production of one or both. One of the subjects preselected for their ability to score high on the psi tasks that were employed in some of these EEG studies was Lalsingh “Sean” Harribance. In a study by Morris et al. (1972), EEG data were collected from Sean while he was engaged in the ESP task of guessing the sex of persons shown in concealed photographs. The overall results of this study were significant (p < 10-12), and a significant positive correlation was found between alpha abundance (percent-time alpha) and the proportion of correct choices (p < .05). In addition, a comparison of alpha abundance just prior to runs and during runs showed that the alpha abundance tended to increase from pre-run to run on the high-scoring runs but not on the chance scoring runs (p < .03). In a second study by Morris et al. (1972), Sean was tested with standard ESP cards. As in the first study, overall results were significant (p < .001) and there was a significant positive correlation between alpha abundance and the proportion of correct choices (p < .005). However, a comparison of alpha abundance just prior to runs and during runs showed no significant

-

EEG and SPECT data

Proceedings of Presented Papers 5

differences in alpha abundance from pre-run to run on either the high-scoring runs or the chance scoring runs. It is notable that a ranking of the usable sessions (for EEG analysis) according to mean deviation from chance correlated significantly with a similar ranking of the sessions according to mean alpha abundance during the run (Spearman rho = + 1.00, p < .05, two-tailed). Morris et al. concluded that the relationship between high alpha abundance and high ESP scoring may therefore exist in part as a between-session phenomena. Other interesting EEG results were found in an experiment by Kelly and Lenz (1976), in which Sean was tested with a binary electronic random number generator. Although the overall results of this experiment were nonsignificant, the results of MANOVA analyses indicated that the power spectrum of the pre-response EEG appeared to discriminate, to a statistically significant degree, between hitting and missing responses. The main source of significant discrimination was excess power on missing trials, especially at the upper end of the frequency range associated with alpha (12-13Hz). It was independently significant in both hemispheres, and appeared somewhat larger on the right side. Since the flourish of studies conducted over twenty years ago, very few EEG studies examining the psychophysiological correlates of psi have been published. In particular, no other EEG studies involving Sean Harribance have been published since that time. Within the last decade, most of the psi research using EEG has been reported and published by Norman S. Don, Bruce E. McDonough, and Charles A. Warren of the Kairos Foundation and the University of Illinois at Chicago. Interestingly, Don and colleagues have found an increase of power, not only in the alpha range but in other frequency ranges as well, during psi-hitting runs. For example, in perhaps the first published psi study employing frequency-domain topographic mapping (Don, McDonough, & Warren, 1992), a selected subject performed 288 trials on a computer-controlled psi testing system called ESPerciser.TM The subject performed at chance level over all trials (p = .668, one-tailed exact binomial), but performed extremely high on Run 1 (p = .007). Analyzation of the topographic maps of this run revealed a gradient in the theta, alpha, and beta bands, with minimum power at the left-lateral scalp increasing to a maximum at the right-lateral scalp. The authors also found in an earlier study with a different subject who participated in a clairvoyance card-guessing task that the EEG frequency spectrum indicated greater power in the theta and 40-HZ frequency bands over the right cerebral hemisphere for hit trials than for miss trials in a clairvoyance card-guessing task (McDonough, Warren, & Don, 1989). ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- During the first week of April, 1997, Sean visited the Institute for Parapsychology in Durham, North Carolina to participate as a subject in a series of psi experiments conducted by Dr. John Palmer. Motivated by my own interest in examining the EEG data of selected subjects engaged in

-

Alexander et al.

6 The Parapsychological Association Conference

psi tasks, and unaware at this time of any specific EEG results obtained from Sean in previous psi research, I asked Sean if he would accompany me on Saturday to the EEG lab in Raleigh, North Carolina, the site of my doctoral internship in quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG).

2

Sean agreed and allowed me to collect EEG data from him during baseline conditions and psi tasks. This research was exploratory in nature and was not part of a formal experiment. Following Sean’s visit in April, I was invited to spend June 2 - 6, 1997 in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada with Dr. Michael Persinger, Dr. William Roll, and Dr. David Webster for neuropsychological and parapsychological testing of Sean. This research was a follow-up and extension of work done in 1996 by Persinger and Roll. In this paper, I will present the results of the QEEG data collected in Raleigh, North Carolina and subsequent further analyses of these data, along with the psychophysiological data collected in Sudbury. The results of other neuropsychological and parapsychological research conducted in Canada with Sean will be presented in a separate paper.

QEEG DATA COLLECTION (RALEIGH, NC; APRIL 5TH, 1997)

As our time in the EEG lab was limited, data were collected for exploratory research purposes and not for hypothesis testing. Because it is important to have initial EEG assessment data as a baseline, I collected data from Sean under several different conditions and during several different tasks. The primary goal of the EEG data collection was to determine the dominant electrocortical activity and its location while Sean participated in psi tasks. In order to answer these same questions regarding brain activity during successful versus unsuccessful psi tasks, several days of testing, which we were not afforded, would have been required. Therefore, the results presented below indicate the type of electrocortical activity and its location while Sean was engaged in psi tasks irrespective of success.

Method

EEG Recording Procedure

An elastic skull cap made by Electro-Cap International, Inc., consisting of 19 electrodes pre-positioned according to the International 10-20 system, was properly fitted on Sean. A forehead ground was used, and reference electrodes were applied to the left and right earlobes and linked. Electrode gel was applied to the electrodes and impedances for all electrodes were kept at approximately 5 K ohms. The sampling rate was 128/sec. The NeuroSearch-24TM EEG System by Lexicor was used for data acquisition and related software was used for data editing and analysis.

Data Collection

2 Thanks to Dr. Dan Chartier at Medical Biofeedback Services, Inc. for the use of the EEG equipment.

-

EEG and SPECT data

Proceedings of Presented Papers 7

EEG data were collected from Sean in the following three conditions in order to obtain baseline data prior to the psi tasks: eyes-open baseline, eyes-closed baseline, and during the Bender Visual Motor Gestalt Test (Bender, 1938). The primary purpose of administering the Bender-Gestalt was to collect EEG data on Sean while he was drawing but not participating in a psi task. This data could then be used as comparative data for the remote viewing task in which Sean would be drawing during a psi task. The second reason for administering the Bender-Gestalt was to collect data on Sean’s visual motor abilities and brain function. The results obtained from the Bender-Gestalt for the latter purpose will not be discussed in this paper. After baseline data were collected, data were collected on Sean during the following five psi tasks: two psychic readings from photographs, two runs of card guessing with standard ESP cards using the down through method, and one remote viewing trial. One to five minutes of data were collected for each different condition, depending upon the amount of time it took to complete each task. The raw EEG records were visually inspected and any epochs containing eye movement or other artifacts were deleted. Of the remaining epochs, fifteen were chosen from each condition in order to make the analyses across conditions comparable. The data for each condition were then spectrally averaged and topographic brain maps were computed.

Results

The topographic brain maps (see Figure 1) demonstrate that while Sean was engaged in psi tasks, alpha was dominant bilaterally in the paraoccipital region, with alpha power being strongest in the right parietal lobe at electrode placement P4 (see Figure 2). A lack of alpha activity can be seen in the frontal and temporal lobes. This finding is consistent across all psi tasks except for the remote viewing task. During this task, alpha power was strongest in the left occipital region and the alpha activity in general extended midline towards the frontal lobes. More alpha was present during the remote viewing than during the Bender-Gestalt. Slightly more alpha activity can be seen in the temporal lobes and in the frontal lobe in the remote viewing task relative to the other psi tasks. Sean’s electrocortical activity during the psi tasks differed from the activity occurring during baseline conditions. Most notably, during the eyes-open baseline, beta was dominant in the left occipital region and alpha power was strongest in the frontal region. During the Bender Visual Motor Gestalt Test, beta was dominant in the right temporal lobe and in the left occipital region, with alpha being present in the left occipital and frontal central regions

-

Alexander et al.

8 The Parapsychological Association Conference

The topographic maps of the eyes-closed condition are similar to the topographic maps of the psi tasks, perhaps because Sean reported that when his eyes were closed visual images spontaneously entered his mind as they did during the psi tasks. In general, more frontal alpha activity can be seen in the eyes-closed baseline than in the psi task conditions. It should be noted that throughout all eight conditions, there is a lack of electrocortical activity in the left temporal lobe. This lack of activity was not due to a faulty electrode.

SUBSEQUENT EEG ANALYSIS (REDINGTON SHORES, FL; OCTOBER 7TH, 1997)

In October, 1997, I sent the raw EEG data files on Sean that I collected in April to Dr. Robert Thatcher at Applied Neuroscience Laboratory in Redington Shores, Florida for subsequent analysis and comparison with his normative Lifespan Reference EEG Data Base (Thatcher, 1995). I felt that it was important to have Sean’s EEG data compared to that of the normative data base so that the severity and anatomical location of any abnormalities could be evaluated. Dr. Thatcher edited the raw EEG data from the eyes-closed baseline condition and removed any artifacts. He then analyzed the data for EEG coherence, phase, amplitude differences, and relative power, and compared these measures to the data in his Lifespan Reference EEG Data Base using the appropriate age-matched group.

Figure 1. Topographic brain maps of the three baseline conditions (top row) and three psi task conditions (bottom row). Each topographic map depicts a top-down view of the head

with the nose pointing forward. The numbers 1 and 2 point to the areas where alpha power is strongest, with areas designated by a 1 having more power than areas designated by a 2.

The numbers 3 and 4 point to areas where alpha power is the least, with areas designated by a 4 having less power than those designated by a 3.

Figure 2. Schematic of the International 10-20 electrode placement system with electrode placement P4 (right parietal lobe) circled.

This schematic could be superimposed upon the topographic maps in Figure 1 as a reference to electrode placement.

-

EEG and SPECT data

Proceedings of Presented Papers 9

Results

Results of the analysis and comparison of Sean’s EEG data with the Lifespan Reference Data Base show deviations from the reference data base that are primarily bilateral, involving the occipital, temporal, and frontal regions. Sub-optimal neural function is indicated, especially in the frontal and temporal cortical regions. Results of EEG coherence analysis indicate that there may be reduced functional connectivity, especially in the bilateral central and frontal regions.

EEG DATA COLLECTION (SUDBURY, ONTARIO, CANADA; MAY 27TH, 1996)

Three days of neuropsychological, cognitive, and personality assessment were completed with Sean in order to discover any potential anomalies that might help explain the psi phenomena that Sean experiences. At the end of the first test day, Sean’s electrocortical activity was measured during a period of relaxation, as clinically relevant neuroelectrical anomalies are often displayed during rest periods when they have been preceded by maintained psychological activity. The EEG measures taken are indices of attention and regional anomalies, and they are not equivalent to a complete neurological EEG assessment.

Method

While seated in a comfortable chair, silver-disc electrodes were attached to Sean’s scalp with EC-2 cream. Bipolar recordings of electrocortical activity from the occipital, temporal, and frontal regions were collected for 20 minutes. During the next 10 minutes, intrahemispheric and interhemispheric electrical activity was measured between the left and right hemisphere for temporooccipital, frontotemporal, and frontooccipital positions.

Results

Beta frequency was dominant rostrally over the prefrontal, temporal, and occipital lobes, while a near-continuos train of alpha rhythms dominated the posterior regions. Because Sean was frequently vocalizing, fast beta activity dominated the temporal and frontal regions. No evidence of classical epileptiform signatures was found. Bilateral interhemispheric comparisons in the temporofrontal regions were coherent and dominated by fast beta activity. Occipitotemporal comparisons were anomalous, as the left hemisphere displayed more frequent episodes of slow alpha rhythms than did the right hemisphere. A marked elevation of activity over the right hemisphere was suggested by a conspicuous superimposition of a higher frequency source upon the fundamental (alpha). Interhemispheric comparisons in the frontooccipital regions showed relatively coherent trains of alpha rhythms.

-

Alexander et al.

10 The Parapsychological Association Conference

SPECT BRAIN SCANS (SUDBURY, ONTARIO, CANADA; JUNE 4TH & 6TH, 1997)

Function in the brain can be detected by Single-Photon Emission Computerized Tomography (SPECT). With SPECT, a commercially available tracer which emits photons is injected or inhaled. The emitted photons are detected and the information gained provides a three dimensional graphic image of metabolic activity within the brain. It is inferred that the active areas of the brain are the functional areas associated with the tasks performed while the tracer is being absorbed.

Method

Two Tc-99m SPECT ECD brain scans were completed with Sean in order to contrast a baseline resting condition with a psi task condition. For both scans, Dr. Webster injected Sean with a tracer prior to the psi task condition and the baseline resting condition. This allowed the tracer to be absorbed by the brain during the activities assigned to the two different conditions. During the psi task condition on June 4th, Sean gave a psychic reading of about 45 minutes duration to a patient of Dr. Persinger. During the resting baseline condition on June 6th, Sean relaxed for about an hour. After each condition, Sean was taken to Sudbury General Hospital for the SPECT brain scan, which took about 45 minutes to complete.

Results

The results of the SPECT brain scan indicate the areas of Sean’s brain that were active while he was in the psi task condition and the baseline resting condition. The most pronounced finding was increased uptake of the tracer, relative to cerebellar uptake, in the paracentral lobule and in the superior parietal lobule of the right hemisphere during the psi task condition. This was not found during the baseline condition. Also, a small focal defect in approximately Area 44, adjacent to the Sylvian fissure, was seen during the psi task condition but not during the baseline condition. The significance of this small focal defect is unknown. Other relevant findings include some mildly decreased uptake of the tracer in the left basal ganglia, left thalamus region, midline thalamus area, and in the frontal areas of the brain in both conditions. These results suggest that there may be some mild decrease of function in these areas. Both conditions were also associated with a decrease in the uptake of the tracer (hypoperfusion) bilaterally in the temporal regions. This hypoperfusion was more pronounced in the left temporal region than the right, with slight relative improvement in the right during the baseline condition.

DISCUSSION

Despite the fact that the data presented in this paper are from several different studies that have been conducted by different experimenters in different laboratories over the years, a consistent trend in the data is present throughout. This consistency suggests a stable neurophysiological correlate which exists between cerebral activity and participation in psi tasks by the selected subject Sean Harribance. The most important finding within these studies was an increase of

-

EEG and SPECT data

Proceedings of Presented Papers 11

activity in Sean’s right parietal lobe while he was engaged in a psi task as compared to when he was not. Specifically, the QEEG data collected in Raleigh showed an increase in alpha power in the right parietal lobe at electrode placement P4 while Sean was engaged in psi tasks, and the SPECT data showed increased metabolic activity in the right parietal region during the psi task condition. Data is not available at this time to demonstrate that psi actually occurred during the psi task conditions while QEEG and SPECT data were collected. However, while Sean was engaged in the psi tasks, alpha was dominant. One may speculate that psi was indeed present as previous research with Sean (Morris et al., 1972) indicates the presence of alpha during high ESP scores. Nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that there is an increase of activity in Sean’s right hemisphere in the parietal region while he is engaged in psi tasks. An important question is why this area of the brain would be activated during psi tasks. The answer may be that the region of the brain that is involved in visual search attention is located in the parietal cortex. When a person is attending to a location in space, the posterior attention network, which is located in the parietal cortex, is activated (Posner & Rothbart, 1991). Regional cerebral blood flow studies show increased blow flow, indicative of neural activity, in the parietal cortex when people attend to spatial locations (e.g., Corbetta et al., 1991). Perhaps psi is attended to and processed in the brain in the parietal cortex via the posterior attention network. Also, it may well be that Sean’s brain has areas that function at a higher than normal level to compensate for areas that function sub-optimally. Data from the SPECT, QEEG and from the Lifespan Reference Data Base comparison indicate a lack of activity or sub-optimal neural function in the frontal and temporal cortical regions in Sean’s brain. Perhaps an increase of activity and function in the parietal lobe helps compensate for these less functional areas. In summary, the results of this paper show that a neurophysiological correlate exists for the selected subject Sean Harribance while he is engaged in psi tasks in the laboratory. The data presented is specific for Sean and may not be applicable to others. Future research with other selected subjects is needed in order to determine if these results can be replicated between subjects.

REFERENCES

American Society for Psychical Research, Research Committee. (1959). Report of the Research Committee for 1958. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 53, 69-71.

Bender, L. (1938). A Visual Motor Gestalt Test and its clinical use. American Orthopsychiatric Association Research Monograph, No. 3.

Cadoret, R. J. (1964). An exploratory experiment: Continuous EEG recording during clairvoyant card tests. Journal of Parapsychology, 28, 226.

-

Alexander et al.

12 The Parapsychological Association Conference

Corbetta, M., Meizin, F. M., Shulman, G. L., & Petersen, S. E. (1991). Shifting attention in space, direction versus visual hemifield: Psychophysics and PET. Journal of Blood Flow and Metabolism, 11, 909.

Don, N., McDonough, B., & Warren, C. (1992). Topographic brain mapping of a selected subject using the ESPerciser: A methodological demonstration and an exploratory analysis. Proceedings of the Parapsychological Association 35th Annual Convention, Las Vegas, NV, 36-50.

Honorton, C. (1969). Relationship between EEG alpha activity and ESP card-guessing performance. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 63, 365-374.

Honorton, C., & Carbone, M. (1971). A preliminary study of feedback-augmented EEG alpha activity and ESP card-guessing performance. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 65, 66-74.

Honorton, C., Davidson, R., & Bindler, P. (1971). Feedback augmented EEG alpha, shifts in subjective state, and ESP card-guessing performance. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 65, 308-323.

Kelly, E. F., & Lenz, J. (1976). EEG correlates of trial-by-trial performance in a two-choice clairvoyance task: A preliminary study. In J. D. Morris, W. G. Roll, & R. L. Morris (Eds.), Research in Parapsychology 1975 (Vol. 4, pp. 22-25). Metuchen, N. J.: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

McDonough, B., Warren, C., & Don, N. (1989). EEG frequency domain analysis during a clairvoyance task in a single-subject design: An exploratory study. In L. A. Henkel, & R. E. Berger (Eds.), Research in Parapsychology 1988 (pp. 38-40). Metuchen, N. J.: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Morris, R. L., & Cohen, D. A. (1969). A preliminary experiment on the relationship among ESP, alpha rhythm and calling patterns. Proceedings of the Parapsychological Association, 6, 22-23.

Morris, R. L., Roll, W. G., Klein, J., & Wheeler, G. (1972). EEG patterns and ESP results in forced-choice experiments with Lalsingh Harribance. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 66(3), 253-268.

Posner, M. I., & Rothbart, M. K. (1991). Attentional mechanisms and conscious experience. In D. Milner & M. Rugg (Eds.), The neuropsychology of consciousness. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Stanford, R. G., & Lovin, C. (1970). EEG alpha activity and ESP performance. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 64, 375-384.

Thatcher, R. W. (1995). Lifespan Reference EEG Data Base. The Use of QEEG Data Bases in the Evaluation and Treatment of Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries. Self-published manual.

Wallwork, S. C. (1952). ESP experiments with simultaneous electroencephalographic recordings. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 36, 697-701.

-

Proceedings of Presented Papers 13

EEG and SPECT data

A STUDY OF THE FEATURES OF OUT-OF-BODY EXPERIENCES IN RELATION TO SYLVAN MULDOON’S CLAIMS1

Carlos S. Alvarado & Nancy L. Zingrone

University of Edinburgh

& Centro de Estudios Integrales de Puerto Rico

ABSTRACT In this paper we will put to test some ideas expressed by “astral projector” Sylvan Muldoon in his 1929 book, The Projection of the Astral Body (with H. Carrington). Based on his numerous OBEs Muldoon wrote about OBE patterns he assumed to be universal. These patterns consisted of lack of thought-clarity and motor coordination while Muldoon was close to the body (under 8 feet), and the experience of shock to the body on rapid and sudden returns. We collected 88 OBE questionnaires from appeals in newspapers and magazines. Based on Muldoon’s experiences and claims it was predicted that we would find a positive and significant correlation between distance from the physical body during the OBE and a measure of thinking and mental clarity, and a similar positive relationship between the distance measure and a measure of control of movements. In addition, we also expected higher levels of thinking and mental clarity and control of movements at specific distances from the body (below and over eight feet from the body). Finally, we predicted a higher frequency of reports of shocks to the body at the end of the experience if the return to the body was sudden and rapid than when returns were slow and gradual. The hypothesis of a positive correlation between rate of control of movements during the OBE and distance from the physical body was confirmed. Similarly, the prediction of a positive relation between clear thinking/mental clarity (one variable) and distance was also confirmed. If the distances were limited to those less than five feet from the body and those over 15 feet from the body, which clearly include those below and above the eight feet range from the body emphasized by Muldoon for control, the difference was significant. The results for thinking and mental clarity and for shocks to the body were not significant. Work such as this has the potential of dispelling myths, of testing the experiences of individuals who have been very influential in the occult and popular literature against the experience of others. This line of work allows researchers to be responsible to the social needs of people who are interested in these issues by producing research that is

1 We wish to thank the Institut für Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygiene, the Parapsychology

Foundation, and the Society for Psychical Research for their financial support. We dedicate this paper to the memory of Karlis Osis, whose explorations of OBE features, and whose courageous studies of the “unconventional” within an unconventional discipline, has inspired us to conduct work such as the study reported in this paper.

-

Alvarado & Zingrone

14 The Parapsychological Association Conference

relevant to their concerns, and which speaks to the materials they read and believe.

INTRODUCTION

In a recent paper one of us (C.S.A.) justified a research program designed to study out-of-body experiences (OBEs) in depth (Alvarado, 1997). This research program pays attention to the features of the experience. These features, consisting of floating sensations, seeing lights, traveling to distant places, seeing the physical body, perceiving oneself in a body similar to the physical or with no body at all, and having feelings of elation, among others, have been documented over the years in surveys and case collections (e.g., Alvarado, 1984; Crookall, 1961, 1964; Giovetti, 1983; Green, 1968; Muldoon, 1936; Muldoon & Carrington, 1951; Osis, 1979; Poynton, 1975; Twemlow, Gabbard, & Jones, 1982). This program of research is based on the assumption that there is much to learn by studying OBE features beyond their incidence. One approach is to see if the frequency of some features of the OBE is affected in some way by their interaction with such variables as the mode of OBE induction, whether the circumstances surrounding the experience were near-death, other OBE features, or demographic circumstances (Alvarado, 1984, 1997; Alvarado & Zingrone, 1997; Gabbard, Twemlow & Jones, 1981; Irwin, 1985). One way to explore issues of this sort further is by studying the OBE patterns of frequent OBErs, and to test if the experience characteristics of frequent OBErs can be found in other individuals as well. The literature on this subject is rich, as seen in the writings of Fox (1939), Harary (1978), Monroe (1971), Muldoon (Muldoon & Carrington, 1929), Turvey (1911), Vieira (1986), and many others. Some of these writings are very influential in that they shape beliefs about OBEs in the popular culture. As we have argued elsewhere (Alvarado & Zingrone, 1996a, 1996b) we have a responsibility as researchers to explore this popular and occult literature to determine whether the prescriptions and rules promoted in this type of literature can be generalized to other individuals. It is our belief that scientific research into experiences like OBEs is necessary because of the tendency for the general public to initiate practices and form beliefs on the basis of these books, steps which may or may not be warranted, which may or may not be psychologically adaptive. In this paper we will focus on the writings of “astral projector” Sylvan Muldoon. Muldoon was a well-known gifted individual who had thousands of OBEs throughout his life (for biographical information see Blackmore, 1982; and Rogo, 1978). His writings are among the most influential in OBE history as they speak to the experience of those who have had many OBEs. Muldoon is best known for his book, The Projection of the Astral Body (Muldoon & Carrington, 1929), co-authored with psychical researcher Hereward Carrington, in which Muldoon described his own OBEs in detail. Even to this day, the book is frequently cited as an exemplar of OBE autobiographical accounts (e.g., Alvarado & Zingrone, 1997; Blackmore, 1982; Irwin, 1985; Mishlove, 1993). In later books Muldoon (1936; Muldoon & Carrington, 1951) compiled other individuals’ OBEs and commented on the significance of them. In The Projection of the Astral Body Muldoon derived some “principles” from his many experiences (Muldoon &

-

Proceedings of Presented Papers 15

The features of out-of-body experiences

Carrington, 1929). For example, for Muldoon there was mental confusion and difficulty in controlling the movements of the OBE body when he felt himself to be close (within 8 feet or so) to his physical body. In addition, he claimed that feelings of shock to the physical body on return were more frequent when the return occurred suddenly than when it occurred gradually. (This particular relationship was found in a previous study by the present authors [Alvarado & Zingrone, 1997]). Because Muldoon described his experiences and derived “principles” from them in a more precise and consistent way than other individuals who have written autobiographical accounts of their OBEs (e.g., Fox, 1939; Monroe, 1971; Harary, 1978; Turvey, 1911; see also the reviews of autobiographical accounts of Blackmore, 1982; Irwin, 1985; and Rogo, 1978), we used some of his descriptions and ideas to generate hypotheses to see if his experiences may be generalized to the experiences of other individuals. Consequently, in the present study we predicted more mental clarity and motor control in experiences in which the reported separation from the physical body was greater than the range specified by Muldoon, as compared to those experiences that occurred close to the body. In addition, we expected a positive and significant correlation between distance from the physical body during the OBE and a measure of thinking and mental clarity, and a similar positive relationship between the distance measure and a measure of control of movements (2 predictions). We also hypothesized a higher frequency of reports of shocks to the body at the end of the experience if the return to the body was sudden and rapid than when returns were slow and gradual.

METHOD

Participants

The participants selected themselves on the basis of responses to queries for OBEs published in a variety of sources. Usable replies for the OBE questionnaire were received from 88 individuals. Because not everyone answered all the questions the demographics and other questions are not always based on the whole sample. Of the 87 who provided information about their sex, 62% percent were female and 38% were male. Their ages ranged from 20 to 80 with a mean of 51.76 (N = 86, SD = 14.67). The mean age at the time of the OBE was 33.12 (N = 81, Range: 5-78, SD = 14.98). Out of 87 respondents to the question about nationality, 88% described themselves as from Great Britain. The rest claimed they were Americans (8%), Italians (2%), Sri Lankans (1%), and New Zealanders (1%). Out of 71 participants who indicated where in Great Britain they were born, 61% said Scotland and 39% said England. Other demographic details will be described in a different article now in preparation. A second questionnaire was mailed at a later date asking about parapsychological experiences and including some psychological scales, but this part of the study is not relevant for the present analyses and will be reported elsewhere.

-

Alvarado & Zingrone

16 The Parapsychological Association Conference

Procedure

Several letters were sent to newspapers in Scotland which asked people who have had OBEs, and who were willing to participate in a study involving answering questionnaires, to get in contact with the researcher. Letters were also published in spiritualist and psychical research periodicals from Great Britain and posted to two on-line discussion groups of parapsychological topics on the Internet. Detailed information about these publications is available from the authors. All the call for cases included the following question: “Have you ever had an experience in which you felt that ‘you’ were located ‘outside of’ or ‘away from’ your physical body; that is, the feeling that your consciousness, mind, or centre of awareness was at a different place than your physical body?” Potential respondents, if they could answer yes to the question and were willing to complete questionnaires, were instructed to write to C.S.A. at the Department of Psychology of the University of Edinburgh. They were assured that all communications would be kept confidential.

Questionnaire

The OBE questionnaire had 16 pages (a copy may be obtained from the first author). It started with demographic questions (11 items), and with a question about where or how the participant heard about or came in contact with, the project. After this there were two questions about frequency and level of control of OBEs. The participant was asked to describe his or her most recent OBE, or the only one they had experienced. A whole page was provided for this but they were told that additional paper could be used if necessary. After the description, respondents were told that the questions should be answered in terms of the experience described. The rest of the questionnaire consisted of questions about the circumstances surrounding the experience, about visual experiences, auditory experiences, kinesthetic sensations, cognitive and emotional aspects, and other aspects. Many of the questions had several sections that asked for details about the particular claims.

Analyses

The data was entered into the StatPac Gold 4.5 statistical software program. Frequency-based analyses were assessed using the chi-square test. Analyses based on scores were analyzed with Spearman Rank Order correlations, and with Mann-Whitney U Tests. Effect sizes (r) for the z values generated by the Mann-Whitney U test were calculated using the equation presented by Rosenthal (1991, p. 19): z /√N.

RESULTS

Tables 1 and 2 present the descriptive statistics relevant to the OBE variables under study. Previous findings based on Muldoon’s experiences (Alvarado & Zingrone, 1997) regarding a higher frequency of shocks to the body on rapid and sudden returns to the body, as compared to slow and gradual returns, were not replicated. Out of four cases with slow and gradual returns, 50% had shocks, as compared to 24% of the 38 cases of rapid and sudden return (N = 42, ?2[1] =

-

Proceedings of Presented Papers 17

The features of out-of-body experiences

.29, p = .30, 1t, phi = .08). Unfortunately, the low number of slow and gradual returns suggests this may not have been a proper test of the hypothesis.

Variable N Percent

Distance from the physical body 80

Less than 1-6 inches 6 7.5 6 inches - 1 foot 1 1.3 1-3 feet 11 13.8 3-5 feet 15 18.8 5-15 feet 23 28.8 15-25 feet 9 11.3 25 feet - several miles 7 8.8 Miles - other countries,

or far away 5 6.3 Distance varied 3 3.8

Thinking and mental clarity compared with how you felt before the experience 82

Worse 6 7.3 Same 50 61.0 Improved 26 31.7

Control of OBE movements 68

Not at all 38 55.9 Sometimes 5 7.4 Most of the time 11 16.2 Always 14 20.6

Variable N Percent Rate of return to the body 69

Slowly, gradually 4 5.8 Somewhat slowly 14 20.3 Somewhat rapidly 10 14.5 Rapidly, suddenly 41 59.4

Shock felt on return 77

No 60 77.9

-

Alvarado & Zingrone

18 The Parapsychological Association Conference

Yes 17 22.1

Table 1: Frequency of OBE Variables Used in the Analyses Another of the hypotheses based on Muldoon’s experiences was a positive correlation between rate of control of movements during the OBE and distance from the physical body. This was confirmed (rs[65] = .36, p = .002, 1t). Similarly, the prediction of a positive relation between clear thinking/mental clarity (one variable) and distance was also confirmed (rs[74] = .21, p = .04, 1t). If the distances were limited to those less than five feet from the body (N = 29, Mean = .52, Mean Rank = 20.79) and those over 15 feet from the body (N = 18, Mean = 1.44, mean Rank = 29.17), which clearly include those below and above the eight feet range from the body emphasized by Muldoon for control, the difference was significant, z = 1.83, p = .03, 1t, r = .27. The results for thinking and mental clarity were not significant. They were as follows: Below 5 feet from body (N =17, Mean = 2.12, Mean Rank = 13.38), over 15 feet from the body (N = 11, Mean = 2.36, Mean Rank = 16.23), z = .89, p = .19, 1t, r = .17. Variables N Range* Mean Median SD Distance from the physical body 77 1-8 4.66 5.00 1.91 Thinking and mental 82 1-3 2.24 2.00 .58 clarity compared with how you felt before the experience Control of OBE 68 0-3 1.01 0 1.24 movements Rate of return to 69 1-4 3.28 4.00 .98 the body *The ranges for each variables were as follows: Distance from the physical body (1 [less than 1 to 6 inches away] - 8 [other countries/far away]), thinking and mental clarity (1 [worse] - 3 [improved]), control of OBE movements (0 [not at all] - 3 [always]), rate of return (1 [slowly, gradually] - 4 [rapidly, suddenly]).

Table 2: Ranges, Means, Medians, and Standard Deviations of OBE Variables

-

Proceedings of Presented Papers 19

The features of out-of-body experiences

DISCUSSION

The analyses related to Muldoon’s experiences supported his views of the general characteristics of OBEs to some extent. There were significant positive correlations between measures of thinking and mental clarity during the experience, and control of movement as these two variables were related to distance from the physical body. This supports Muldoon’s personal experiences in which he experienced better levels of mental clarity and control of movements farther from rather than closer to the body. The contrasts that took the extremes above the 8 feet range postulated by Muldoon to be critical (that is below 5 feet and 15 feet and above) were significant only for control of movements, however.

The prediction regarding shocks was not confirmed. Nonetheless we combined the significance levels of the present study (p = .30, 1t) with that of the previous study (Alvarado & Zingrone, 1997, p = .005, 1t). This yielded a Stouffer z of 2.21 (p = .01, 1t). Further work needs to be conducted on this point, because no conclusion can be drawn from only two studies.

A problem with these type of analyses is how to explain the findings. This research has not been guided by any particular theoretical model. However, we may speculate that when an individual is aware he or she is close to the body this may affect their mental state and their ability to coordinate their movements while having an OBE. Maybe closeness to the body reminds the experiencer of the state they are in and consequently leads to a reaction that interferes in some way with the utilization of the psychological resources assumed to be behind the manifestation of the OBE. This is only a vague speculation.

Although our study does not contribute to the testing of OBE theoretical models it is important to realize that the type of comparisons conducted here are important in that they allows us to explore the ideographic and nomothetic dimensions of OBE phenomenology. The OBE patterns of a single individual (Muldoon) may not generalize to other persons. After all, individuals like Muldoon seem to be rare. But the challenge of the research is to find out if there are aspects that can be generalized. Consequently, work such as this has the potential of dispelling myths, of testing the experiences of individuals who have been very influential in the astral projection lore for many years. This line of work allows researchers to be responsible to the social needs of people who are interested in these issues by producing research that is relevant to their concerns, and which speaks to the materials they read and believe. As such, we hope that future work will examine further the features experienced by Muldoon, as well as those experienced by other individuals who have written autobiographical accounts (e.g., Fox, 1939; Monroe, 1971; Harary, 1978; Turvey, 1911).

REFERENCES Alvarado, C.S. (1984). Phenomenological aspects of out-of-body experiences: A report of three studies.

Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 78, 219-240.

-

Alvarado & Zingrone

20 The Parapsychological Association Conference

Alvarado, C.S. (1997). Mapping the characteristics of out-of-body experiences. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 91, 15-32.

Alvarado, C.S., & Zingrone, N.L. (1996a). The forgotten phenomena of parapsychology. EHE News, 3, 22-24.

Alvarado, C.S., & Zingrone, N.L. (1996b). La parapsicología y las tradiciones espiritistas y ocultistas: Ampliando el alcance del estudio de las experiencias humanas. In A. Parra (Ed.), Segundo Encuentro Psi 1996 (pp. 23-27). Buenos Aires: Instituto Argentino de Psicología Paranormal.

Alvarado, C.S., & Zingrone, N.L. (1997a). Out-of-body experiences and sensations of “shocks” to the body. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 61, 304-313.

Blackmore, S.J. (1982). Beyond the body: An investigation of out-of-the-body experiences. London: Heinemann.

Crookall, R. (1961). The study and practice of astral projection. London: Aquarian Press.

Crookall, R. (1964). More astral projections: Analyses of case histories. London: Aquarian Press.

Fox, O. [1939]. Astral projection: A record of out-of-the-body experiences. London: Rider.

Gabbard, G.O.,Twemlow, S.W., & Jones, F.C. (1981). Do near-death experiences occur only near death? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 169, 374-377.

Giovetti, P. (1983). Viaggi senza corpo. Milano: Armenia.

Green, C.E. (1968). Out-of-the-body experiences. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Harary, S.B. (1978). A personal perspective on out-of-body experiences. In D.S. Rogo (Ed.), Mind beyond the body: The mystery of ESP projection (pp. 260-269). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Irwin, H.J. (1985). Flight of mind: A psychological study of the out-of-body experience. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Mishlove, J. (1993). The roots of consciousness (2nd ed.). Tulsa: Council Oaks.

Monroe, R. (1971). Journeys out of the body. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Muldoon, S.J. (1936). The case for astral projection. Chicago: Ariel Press.

Muldoon, S.J., & Carrington, H. (1929). The projection of the astral body. London: Rider.

Muldoon, S.J., & Carrington, H. (1951). The phenomena of astral projection. London: Rider.

Osis, K. (1979). Insider's view of the OBE: A questionnaire study. In W.G. Roll (Ed.), Research in parapsychology 1978 (pp. 50-52). Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press .(Abstract)

Poynton, J.C. (1975). Results of an out-of-the-body survey. In J.C. Poynton (Ed.), Parapsychology in South Africa (pp. 109-123). Johannesburg: South African Society for Psychical Research.

Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research (revised edition). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Twemlow, S.W., Gabbard, G.O., & Jones, F.C. (1982). The out-of-body experience: A phenomenological typology based on questionnaire responses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 450-455.

Turvey, V.N. [1911]. The beginnings of seership. London: Stead's Publishing House.

-

Proceedings of Presented Papers 21

The features of out-of-body experiences

Vieira, W. (1986). Projeciologia: Panorama das experiências da consciência fora do corpo humano. Rio de Janeiro: Author

-

Delanoy et al.

22 The Parapsychological Association Conference

A DMILS STUDY WITH EXPERIMENTER TRAINEES1

Deborah L. Delanoy & Robert L. Morris

Psychology Department, University of Edinburgh, and

Institut für Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygiene (IGPP), Freiburg i. Br., Germany

ABSTRACT

A thirty-six session DMILS (direct mental interaction with living systems) study was conducted with agents attempting to activate and calm the electrodermal activity (EDA) of a receiver, at pseudo-random intervals. Both participants were housed in special electromagnetically and acoustically shielded rooms. Experimenters were drawn from an experimenter training course conducted at the Institut für Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygiene. Each trainee conducted six DMILS sessions acting as the experimenter. To gain experience in all aspects of the DMILS environment, the trainees took turns acting as agent and receiver for the first half of the study. During the second half, experimenters worked with other friends and colleagues. Overall there was a non-significantly greater level of EDA during the activate periods than the calm (Stouffer Z= 0.94; effect size (r) = .16). In the 18 sessions conducted with the six trainee experimenters also acting as agent and/or receiver, the results showed slightly greater EDA during calming periods (Stouffer Z = -0.082; es (r) = -.02). In the 18 sessions where friends/colleagues participated, greater EDA was found during the activate periods, with the difference between activate and calm approaching significance (Stouffer Z = 1.417, p = 0.07, 1t; es (r) = .33). These findings are consistent with those from other DMILS studies, having effect sizes falling within the 95% confidence intervals derived from a recent DMILS EDA meta-analysis (Schlitz & Braud, 1997). A significant release-of-effort effect (Stouffer Z = 1.826, p = 0.03,1t; es (r) = .43) was found for the non-trainee population, and in both populations the release-of-effort effects were larger than the primary effects. These findings suggest the possible utility of longer interaction periods and advise against the use of shorter rest periods. Local sidereal time (LST) effects were explored for the first time in a DMILS study. Preliminary findings (with very small n’s) support those obtained from anomalous cognition studies by Spottiswoode (1997), with an approximate 400% increase in mean session z within +/- 2 hour period of LST 13.5 (N = 3, mean z = 0.629; where the overall N = 36, mean overall session z = 0.157). Similarly, z’s from sessions conducted within +/- 2 hours of LST 18.5 (N = 4, mean z = 0.076) were lower than the overall mean session z.

1 The authors thank the IGPP staff, M. Binder, H. Bösch, L. Hofmann, U. Kodjoe, G. Mayer, and R.

Schneider, who participated in this study as experimenters, agents and receivers, for their generous contribution of time, effort and skill. We are most grateful to the IGPP for their funding and support of the study. Also, we are obliged to James Spottiswoode who kindly provided the LST information and calculations for our study.

-

A DMILS study with experimenter trainees

Proceedings of Presented Papers 23

INTRODUCTION

Living systems have been used as targets in psi research for many years (see Morris, 1977 for a summary of early work) and this work is intimately linked with various notions of psychic healing (e.g., Solfvin, 1984). However, such research has recently grown in popularity due to the successful outcomes of a progressive research program carried-out by William Braud and his colleagues (for an overview, see Braud & Schlitz, 1991, and Schlitz and Braud, 1997). Braud further developed existing methodologies for working with living systems, and labelled the basic procedure as DMILS (direct mental interaction with living systems) studies (e.g., Braud, 1994). Currently, DMILS protocols are being increasingly used to address process-oriented questions (e.g., Watt et al., 1997; Delanoy and Sah, 1994). Of special interest are the procedures involving an agent who by mental intentions attempts to selectively activate or calm a sensorially-isolated receiver, as measured by shifts in the receiver’s electrodermal activity (EDA). These effects have been obtained both by Braud and associates (Braud & Schlitz, 1991; Braud et al., 1993a, 1993b) and by others (e.g., Radin et al., 1995; Schlitz & La Berge, 1994; Delanoy & Sah, 1994; Watt et al., 1997). Although its potential artifacts require consideration, nonetheless EDA is a non-intrusive, accessible measure and one of the more straightforward physiological indicators of arousal (see, e.g., Dawson et al., 1990, for a recent methodological review). The current study is in part an attempt to obtain evidence of an agent-mediated effect upon a receiver’s EDA in a new laboratory, with multiple experimenters and with unusually stringent sensory shielding between the agent and receiver. Effects obtained in parapsychology have usefulness in process-oriented research primarily to the extent that they can be conceptually replicated and extended in other laboratories, with different experimenters and experimental facilities. The authors are currently involved in the development of a new multi-purpose interpersonal psi testing facility at the Institut für Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygiene (IGPP) in Freiburg, Germany, including the training of new researchers (via an experimenter training course and hands-on experimental participation). The first study conducted in the new facility, reported herein, utilised an EDA DMILS procedure. The study involved interested IGPP staff as both experimenters and research participants, to provide them with further training as parapsychological researchers. The experimental setting, described below, incorporates the use of state of the art shielded rooms for both agent and receiver, as well as computer-controlled psychophysiological monitoring and management of experimental conditions. The primary goals of this study were threefold: 1stly, to attempt replication of the basic EDA DMILS effect with new experimenters in a new facility; 2ndly, to provide an opportunity to evaluate the new facility for its appropriateness for DMILS and related research; and, 3rdly, to train potential new parapsychological researchers by providing first-hand experience with a challenging research protocol while gaining familiarity with various roles, as experimenter, agent and receiver, and also to provide experimenter experience working with a more usual participant population.

-

Delanoy et al.

24 The Parapsychological Association Conference

In achieving the first goal, various effects noted in other EDA DMILS studies would be sought. For example, Radin, Taylor and Braud (1993) found a significant release-of-effort effect in the first DMILS study conducted at the Edinburgh University parapsychology unit, where the activate or calming intentions appeared to be carried over into the following rest periods. As similar effects had been informally noted by the authors in other Edinburgh DMILS studies, it was of interest to see whether these effects would be present in the Freiburg data. Also, as the standard Braud DMILS study has the experimenter also acting as the agent, it was of interest to explore the outcomes of the trainees’ own data (who would be contributing sessions both as experimenter and as agent/receiver), to look for similarities and/or differences between the two data sets. Different agent and receiver populations would be used in this study, with one population comprised solely of the trainees and the other involving external participants. Therefore, the two populations would be explored for any scoring differences. The sessions contributed by each individual trainee would also be explored looking for differences in their overall outcomes, to follow up on the differences between experimenters found in the Wiseman and Schlitz (1996) EDA DMILS (remote staring detection) study. Finally, given the recent finding of a relationship between local sidereal time (LST) and anomalous cognition study outcomes (Spottiswoode, 1997), these data would be explored for any similar findings.

METHODS

The study was designed as a straightforward replication of Braud and colleagues’ standard EDA-based DMILS procedure, comparing activate and calming periods within sessions (see Braud & Schlitz, 1991). However, unlike Braud’s traditional EDA studies, the experimenter did not also serve as the agent, except in one session. Instead an experimenter worked with two participants, an agent and a receiver, as in some previous Edinburgh DMILS studies (e.g., Delanoy & Sah, 1991). Trainee experimenters would first conduct sessions amongst themselves, trading roles as experimenter, agent and receiver. When they were confident acting as experimenters, they were to bring other IGPP colleagues and friends to be agents and receivers.

Participants

Six interested IGPP staff members, who were participating in an “experimenter training course” (offered by the authors), each agreed to act as experimenters in six sessions. Furthermore, they agreed to serve as agents and receivers in approximately six other sessions conducted by the other experimenters. They were encouraged to serve three times each as an agent and a receiver. After conducting approximately three sessions as experimenters with their co-workers, they were to serve as experimenters in three further sessions involving other friends and colleagues as participants. None of the experimenters had previous experience working in a DMILS study; two had prior experience in psi studies, one with RNG-PK studies, and another with an ESP study. The first author participated as an observer/trainer in the initial “within experimenter” sessions (approximately 6 sessions), and participated as an agent or receiver in four sessions.

-

A DMILS study with experimenter trainees

Proceedings of Presented Papers 25

Experimental Facility

All sessions were conducted in an experimental suite of three rooms in the new offices of the Institut für Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygiene, located on the first and second floors of an office building in downtown Freiburg. Each end room of the three room suite contain a customised acoustically and electromagnetically shielded cabin, purchased from the German branch of the international Industrial Acoustics Company (IAC; Industrial Acoustics Company, Gmbh, Sohlweg 17, 41372 Niederkrüchten, Germany). See Appendix 1 for a floor plan of the laboratory facility. The receiver’s cabin is double-walled with a well-padded reclining chair, dimmer lights adjusted to the receiver’s preference (a relatively bright level was suggested to help the receiver maintain alertness), and a computer monitor display showing a pleasant abstract screen saver with randomly changing patterns. The agent’s cabin is triple-walled with a reclining chair identical to the responder’s, dimmer ceiling lights lit to the agent’s preferred degree of brightness, and a computer monitor displaying a graphical representative of the receiver’s EDA and agent activity instructions. The central room contains the experimenter’s console and computer equipment, as well as a comfortable meeting area with an upholstered sofa and arm chairs. Acoustical attenuation tests have been conducted between the rooms as well as from inside to outside of each room. Between cabins (from the interior of the agent’s cabin to that of the receiver) the acoustic shielding ranged from approximately 65dB at 60 Hz to between 90 - 100dB from 100 - 6000Hz. Also, the rooms have a degree of electro-magnetic shielding (contact the first author for further shielding specifications).

Psychophysiological Monitoring System

The data were collected using a I-410 General Purpose System (produced by J & J Engineering, Inc.), supplied, with computer and applications, by Physiodata, Inc. (Bainbridge Island, WA, USA). Paul Stevens (of the Koestler parapsychology unit, Edinburgh University) created a program to monitor and process the experimental data acquisition and control the presentation of pseudo-randomised instructions to the agent. The data from each session was automatically saved onto the computer’s hard disk, onto a Zip file, and hard copy was automatically printed of each session. Psychophysiological monitoring was accomplished by electrodes (10 mm, silver/silver chloride electrodes) attached to the distal phalanges of non-dominant hand, as recommended by Boucsein (1992), by means of velcro bands. Electrode paste (i.e., Sigma Creme; Parker Laboratories, Inc. and Femilind Gel, Johnson and Johnson) was used to improve conductivity. EDA was sampled 18 times per second, and activity summed to create an overall activity level for each 26.6 second interaction period. The receivers’ EDA was recorded for 17.7 minutes during each session. During this period there were 40 agent/receiver interactions periods, comprised of 10 activate and 10 calm sending

-

Delanoy et al.

26 The Parapsychological Association Conference

periods, interspersed by 20 rest periods, where each period was of 26.6 seconds duration (e.g., rest - activate - rest - calm - rest - calm -...). Paired activate and calm periods were presented to the agent in a pseudo-randomised order within each session and from session to session. The randomisation was controlled by an algorithm within the computer program; no experimental participants (including the experimenter) were aware of the ordering before the session. The agent became aware of the randomised order only as the intentional instructions were presented to them during the session; the experimenter and receiver remained blind to the ordering throughout the data acquisition period. A monitor display conveyed to the agent a graphical representation of the on-going EDA of the receiver, providing the agent with nearly simultaneous feedback of the receiver’s EDA. The EDA display would restart from the left of the screen, at the start of every 26.6 second period. A written message at the bottom of the monitor display would inform the agent of the intention goal of each period (i.e., calm, activate, or rest).

Procedure

For training purposes, all sessions were handled as if the participants were coming to the lab to take part in a session for the first time, even when the agent and receiver were experimenter trainees. Experimenters would greet participants at the IGPP entry door, and then escort them to the lab suite. They would be offered refreshment (i.e., juice, coffee, tea, biscuits, etc.) and would be seated in the “sitting room” area of the central room of the lab suite. Session description and instructions were interspersed with general conversation about various topics, to enable the experimenter to establish a friendly and trusting rapport with the participants and to help them become relaxed in the experimental environment. Descriptions of the session and study aims were tailored to meet the specific interests of the participants when possible (i.e., the medical implications could be stressed to someone involved with heath care or interested in healing; interconnectedness issues discussed with someone interested in spiritual matters; teachers and/or counsellors could be told about the findings showing interpersonal helping/assisting effects in dyadic situations). The task was presented as a joint effort, involving equal contributions from the agent and receiver. The participants were asked to decide who wished to act as the agent and who as the receiver. If the participants were not sure about this, it was suggested that someone who was a good communicator (good at getting their ideas and wishes across to others) might most enjoy the agent’s role, whereas the receiver role could put greater emphasis upon being attentive and responsive to the communications of others, and of being open and receptive. It was also suggested that the receiver might wish to share with the agent some suggestions that might help the agent convey the activate and calm instructions, i.e., receivers could tell the agent about situations that they found emotionally exciting and exhilarating, and also about ones they thought would calm them. Receivers were instructed to be passively open and receptive to the states being conveyed by the agent during the session. They were to make no attempt to become consciously aware of the

-

A DMILS study with experimenter trainees

Proceedings of Presented Papers 27

agent’s intentions at any given time during the session, but rather to trust that their body would unconsciously respond appropriately. Receivers were asked to remain alert and to let their mind wander during the session, without dwelling too long on any one topic. The agent was encouraged to think of things other than the receiver or study during the rest periods and was given the following strategies to help them convey the appropriate state to the receivers during the interaction periods (calm & activate): 1. Achieve the desired state in their own body with the goal of conveying this to or sharing it

with the receiver. 2. Imagine the receiver in the appropriate state. This may involve imagining the receiver in a

suitable activity, e.g., an exhilarating situation, such as scoring a goal, for the activated condition; and a very quiet, relaxed state, such as sleeping for the calm condition.

3. Interact with the feedback EDA display - “will” it to move a lot in the activate condition and to remain flat and still during calm periods.

Agents were encouraged to use the display of the receiver’s on-going EDA as feedback regarding the success of their sending strategies. The three suggested strategies were presented as guidelines to be used as seemed most appropriate and effective, e.g., the strategies could be used alone or in combination with each other. Also, agents were free to devise their own strategies. To help enhance expectations of and desire for success in the session, the positive outcomes of many other similar studies were mentioned. Also, it was noted how the findings from this study would add Germany to the list of places where such research was being successfully carried out. When the participants fully understood the session procedures, they were given a tour of the rooms (including, for training purposes, the sessions where all participants were trainees). First all three visited the shielded cabin in which the agent would be housed. The screen display was briefly described as were other technical aspects concerning the use of the shielded cabins, such as the opening of the doors and the location of the button to contact the experimenter. It was mentioned that the shielded environments provided a beneficially quiet environment for the two participants, free from outside distractions, and also served to deal in advance with later questions about possible non-psychic, sensory ways in which the participants might have been able to communicate with each other. After being shown the experimenter’s area, the participants were taken to the receiver’s shielded cabin. The receiver sat in the chair and the experimenter attached the electrodes (always referred to as “sensors”) to the receiver, explaining that they should try to keep their hand relatively still during the interaction period. After checking that there were no further questions and that the participants were ready to start the session, the experimenter and agent wished the receiver well, and requested them to make a gentle wish that their body would respond unconsciously to the

-

Delanoy et al.

28 The Parapsychological Association Conference

remote intentions of the agent. The door was then closed. The agent and experimenter returned to the experimenter area to check that the electrodes were recording properly. Then the agent was escorted to the other shielded cabin. By this time a display showing the actual, on-going EDA of the receiver was on the monitor screen. After answering any final questions, the experimenter left the cabin and closed the door. The experimenter then returned to the control area and hit a key to start the data collection. Thus the experimenter decided once exactly when to hit the key to start the session, initiate the randomisation of the calm and activate periods, and so on. The end of the session was signalled to the experimenter via a computerised voice. The experimenter then collected the agent, and both proceeded to the receiver’s cabin. The electrodes were removed and all returned to the experimenter’s area. The experimenter prompted the computer to display a summary of the findings on a monitor. Thus all three participants received feedback as to the session outcome at the same time. The session data were automatically backed-up on to a Zip drive, in addition to hard disk storage. Another computer prompt produced five copies of the summary analyses of the session. The two participants were each given a print-out; one lodged with the investigator (DD), one kept by the experimenter, and a third put in the session log book. The participants were then offered further refreshments, and the session discussed in as much detail as desired. The experimenter ensured the participants had a realistic perspective of their performance during the session before they left the lab, e.g., that the session results should not be taken necessarily as a valid indicator of their ability to perform any such DMILS functions in the course of their daily lives.

HYPOTHESES AND PLANNED ANALYSES

1. The primary hypothesis was that significantly greater EDA would be elicited during the activate periods than during the calm periods, over all the sessions. The main, planned method of analysis would be a Wilcoxon matched-pairs sign test for each session’s data, with the overall measure for the study being a Stouffer Z of the combined sessions’ Wilcoxon z’s. Effect size (r) would be reported, where effect size (es) = Stouffer Z / sqrt (n). Wilcoxon based analyses have been used in previous Edinburgh DMILS studies and elsewhere. For comparison purposes, the analysis and effect size measure used by Braud and his colleagues would also be conducted (described in Braud and Schlitz, 1991). Thus a “percentage influence score” (PIS), would be calculated for each session, and a single sample t-test used to determine overall, across session outcome. 2. Using the primary (Wilcoxon/Stouffer Z) method of analysis, the data would be explored for various internal effects. One-tailed tests were used as directional effects (active EDA > calm

-

A DMILS study with experimenter trainees

Proceedings of Presented Papers 29

EDA) were expected, although given the small sample sizes it was not anticipated that outcomes would actually reach significance at the .05 level. 2 a. The results from individual trainee experimenters would be examined, both when acting as experimenter and when filling other participant roles. 2 b. The results from the different participant populations (i.e., trainee experimenters vs. others) would be explored for differences. (For comparison purpose, PIS-based outcomes will be reported also.) 2 c. PIS score analyses will be used to look for release-of-effort effects (Radin, Taylor, & Braud, 1993) in the rest periods following each interaction period. 3. The data would be examined for the local sidereal effects found by Spottiswoode (1997).

RESULTS

1. The primary hypothesis was not supported, with the difference of EDA during activate and calm periods being in the right direction, but not to a significant degree (n = 36, Stouffer Z = 0.942, p = 0.174, one-tailed). The associated effect size was .16. The PIS-based analysis showed a similar non-significantly greater degree of EDA in the activate periods (df = 35, t = 1.176, p = 0.124, one-tailed), with an effect size = .19.

2

2. a. As anticipated, no individual obtained a significantly greater degree of EDA in activate periods across the six sessions for which they were the experimenter. Five of the experimenters obtained results in the expected directions (activate EDA > calm EDA), with one experimenter obtaining overall results slightly in the opposite direction. Two trainees obtained effect sizes larger than the mean EDA DMILS study effect size of .25 (i.e., .36, & .42). The remaining four effect sizes (.12, .10, .05 and - .11) all fall within the effect size confidence intervals derived by the authors from the recent Schlitz & Braud (1997) EDA DMILS meta-analysis (i.e., effect size confidence intervals: .39 to -.12). See Table 1 for trainee experimenter details. Looking at the trainees’ performances when acting as agent or receiver, four obtained results relatively consistent with those they obtained when acting as experimenter. One had a

2 Three completed sessions were not included in the study analyses for technical and protocol reasons. In one

session, the data was not saved onto any source due to an incorrect session entry (with no available data, no z could be calculated for this session). In the other two sessions, the experimenters did not adhere to the pre-arranged protocol: in one case, an extra session was run by an experimenter (z = -0.866); and in the other, the agent received no EDA feedback from the receiver (z = -0.663). All three sessions were run by different experimenters; two involved only trainee participants.

-

Delanoy et al.

30 The Parapsychological Association Conference