ABC short course: introduction chapters

-

Upload

christian-robert -

Category

Science

-

view

2.371 -

download

0

Transcript of ABC short course: introduction chapters

ABC methodology and applications

Christian P. Robert

Universite Paris-Dauphine, University of Warwick, & IUF

Ecole d’Hiver, Les Diablerets, CH, Feb. 4-8 2016

Outline

1 simulation-based methods inEconometrics

2 Genetics of ABC

3 Approximate Bayesian computation

4 ABC for model choice

5 ABC model choice via random forests

6 ABC estimation via random forests

7 [some] asymptotics of ABC

A motivating if pedestrian example

paired and orphan socks

A drawer contains an unknown number of socks, some of whichcan be paired and some of which are orphans (single). One takesat random 11 socks without replacement from this drawer: no paircan be found among those. What can we infer about the totalnumber of socks in the drawer?

• sounds like an impossible task

• one observation x = 11 and two unknowns, nsocks and npairs

• writing the likelihood is a challenge [exercise]

A motivating if pedestrian example

paired and orphan socks

A drawer contains an unknown number of socks, some of whichcan be paired and some of which are orphans (single). One takesat random 11 socks without replacement from this drawer: no paircan be found among those. What can we infer about the totalnumber of socks in the drawer?

• sounds like an impossible task

• one observation x = 11 and two unknowns, nsocks and npairs

• writing the likelihood is a challenge [exercise]

Feller’s shoes

A closet contains n pairs of shoes. If 2r shoes are chosenat random (with 2r < n), what is the probability thatthere will be (a) no complete pair, (b) exactly onecomplete pair, (c) exactly two complete pairs amongthem?

[Feller, 1970, Chapter II, Exercise 26]

Feller’s shoes

A closet contains n pairs of shoes. If 2r shoes are chosenat random (with 2r < n), what is the probability thatthere will be (a) no complete pair, (b) exactly onecomplete pair, (c) exactly two complete pairs amongthem?

[Feller, 1970, Chapter II, Exercise 26]

Resolution as

pj =

(n

j

)22r−2j

(n − j

2r − 2j

)/(2n

2r

)

being probability of obtaining js pairs among those 2r shoes, or foran odd number t of shoes

pj = 2t−2j

(n

j

)(n − j

t − 2j

)/(2n

t

)

Feller’s shoes

A closet contains n pairs of shoes. If 2r shoes are chosenat random (with 2r < n), what is the probability thatthere will be (a) no complete pair, (b) exactly onecomplete pair, (c) exactly two complete pairs amongthem?

[Feller, 1970, Chapter II, Exercise 26]

If one draws 11 socks out of m socks made of f orphans and gpairs, with f + 2g = m, number k of socks from the orphan groupis hypergeometric H (11,m, f ) and probability to observe 11orphan socks total is

11∑

k=0

(fk

)( 2g11−k

)(m

11

) ×211−k( g

11−k)

( 2g11−k

)

A prioris on socks

Given parameters nsocks and npairs, set of socks

S ={

s1, s1, . . . , snpairs , snpairs , snpairs+1, . . . , snsocks

}

and 11 socks picked at random from S give X unique socks.

Rassmus’ reasoning

If you are a family of 3-4 persons then a guesstimate would be thatyou have something like 15 pairs of socks in store. It is alsopossible that you have much more than 30 socks. So as a prior fornsocks I’m going to use a negative binomial with mean 30 andstandard deviation 15.On npairs/2nsocks I’m going to put a Beta prior distribution that putsmost of the probability over the range 0.75 to 1.0,

[Rassmus Baath’s Research Blog, Oct 20th, 2014]

A prioris on socks

Given parameters nsocks and npairs, set of socks

S ={

s1, s1, . . . , snpairs , snpairs , snpairs+1, . . . , snsocks

}

and 11 socks picked at random from S give X unique socks.

Rassmus’ reasoning

If you are a family of 3-4 persons then a guesstimate would be thatyou have something like 15 pairs of socks in store. It is alsopossible that you have much more than 30 socks. So as a prior fornsocks I’m going to use a negative binomial with mean 30 andstandard deviation 15.On npairs/2nsocks I’m going to put a Beta prior distribution that putsmost of the probability over the range 0.75 to 1.0,

[Rassmus Baath’s Research Blog, Oct 20th, 2014]

Simulating the experiment

Given a prior distribution on nsocks and npairs,

nsocks ∼ N eg(30, 15) npairs|nsocks ∼ nsocks/2Be(15, 2)

possible to

1 generate new valuesof nsocks and npairs,

2 generate a newobservation of X ,number of uniquesocks out of 11.

3 accept the pair(nsocks, npairs) if therealisation of X isequal to 11

Simulating the experiment

Given a prior distribution on nsocks and npairs,

nsocks ∼ N eg(30, 15) npairs|nsocks ∼ nsocks/2Be(15, 2)

possible to

1 generate new valuesof nsocks and npairs,

2 generate a newobservation of X ,number of uniquesocks out of 11.

3 accept the pair(nsocks, npairs) if therealisation of X isequal to 11

Meaning

ns

Den

sity

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

0.00

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

The outcome of this simulation method returns a distribution onthe pair (nsocks, npairs) that is the conditional distribution of thepair given the observation X = 11Proof: Generations from π(nsocks, npairs) are accepted with probability

P {X = 11|(nsocks, npairs)}

Meaning

ns

Den

sity

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

0.00

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

The outcome of this simulation method returns a distribution onthe pair (nsocks, npairs) that is the conditional distribution of thepair given the observation X = 11Proof: Hence accepted values distributed from

π(nsocks, npairs)× P {X = 11|(nsocks, npairs)} = π(nsocks, npairs|X = 11)

Econ’ections

1 simulation-based methods inEconometrics

2 Genetics of ABC

3 Approximate Bayesian computation

4 ABC for model choice

5 ABC model choice via random forests

6 ABC estimation via random forests

7 [some] asymptotics of ABC

Usages of simulation in Econometrics

Similar exploration of simulation-based techniques in Econometrics

• Simulated method of moments

• Method of simulated moments

• Simulated pseudo-maximum-likelihood

• Indirect inference

[Gourieroux & Monfort, 1996]

Simulated method of moments

Given observations yo1:n from a model

yt = r(y1:(t−1), εt , θ) , εt ∼ g(·)

simulate ε?1:n, derive

y?t (θ) = r(y1:(t−1), ε?t , θ)

and estimate θ by

arg minθ

n∑

t=1

(yot − y?t (θ))2

Simulated method of moments

Given observations yo1:n from a model

yt = r(y1:(t−1), εt , θ) , εt ∼ g(·)

simulate ε?1:n, derive

y?t (θ) = r(y1:(t−1), ε?t , θ)

and estimate θ by

arg minθ

{n∑

t=1

yot −

n∑

t=1

y?t (θ)

}2

Method of simulated moments

Given a statistic vector K (y) with

Eθ[K (Yt)|y1:(t−1)] = k(y1:(t−1); θ)

find an unbiased estimator of k(y1:(t−1); θ),

k(εt , y1:(t−1); θ)

Estimate θ by

arg minθ

∣∣∣∣∣

∣∣∣∣∣n∑

t=1

[K (yt)−

S∑

s=1

k(εst , y1:(t−1); θ)/S

]∣∣∣∣∣

∣∣∣∣∣

[Pakes & Pollard, 1989]

Indirect inference

Minimise (in θ) the distance between estimators β based onpseudo-models for genuine observations and for observationssimulated under the true model and the parameter θ.

[Gourieroux, Monfort, & Renault, 1993;Smith, 1993; Gallant & Tauchen, 1996]

Indirect inference (PML vs. PSE)

Example of the pseudo-maximum-likelihood (PML)

β(y) = arg maxβ

∑

t

log f ?(yt |β, y1:(t−1))

leading to

arg minθ||β(yo)− β(y1(θ), . . . , yS(θ))||2

whenys(θ) ∼ f (y|θ) s = 1, . . . ,S

Indirect inference (PML vs. PSE)

Example of the pseudo-score-estimator (PSE)

β(y) = arg minβ

{∑

t

∂ log f ?

∂β(yt |β, y1:(t−1))

}2

leading to

arg minθ||β(yo)− β(y1(θ), . . . , yS(θ))||2

whenys(θ) ∼ f (y|θ) s = 1, . . . ,S

Consistent indirect inference

...in order to get a unique solution the dimension ofthe auxiliary parameter β must be larger than or equal tothe dimension of the initial parameter θ. If the problem isjust identified the different methods become easier...

Consistency depending on the criterion and on the asymptoticidentifiability of θ

[Gourieroux, Monfort, 1996, p. 66]

Consistent indirect inference

...in order to get a unique solution the dimension ofthe auxiliary parameter β must be larger than or equal tothe dimension of the initial parameter θ. If the problem isjust identified the different methods become easier...

Consistency depending on the criterion and on the asymptoticidentifiability of θ

[Gourieroux, Monfort, 1996, p. 66]

AR(2) vs. MA(1) example

true (AR) modelyt = εt − θεt−1

and [wrong!] auxiliary (MA) model

yt = β1yt−1 + β2yt−2 + ut

R codex=eps=rnorm(250)

x[2:250]=x[2:250]-0.5*x[1:249]

simeps=rnorm(250)

propeta=seq(-.99,.99,le=199)

dist=rep(0,199)

bethat=as.vector(arima(x,c(2,0,0),incl=FALSE)$coef)

for (t in 1:199)

dist[t]=sum((as.vector(arima(c(simeps[1],simeps[2:250]-propeta[t]*

simeps[1:249]),c(2,0,0),incl=FALSE)$coef)-bethat)^2)

AR(2) vs. MA(1) example

One sample:

−1.0 −0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

θ

dist

ance

AR(2) vs. MA(1) example

Many samples:

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

01

23

45

6

Choice of pseudo-model

Pick model such that

1 β(θ) not flat(i.e. sensitive to changes in θ)

2 β(θ) not dispersed (i.e. robust agains changes in ys(θ))

[Frigessi & Heggland, 2004]

ABC using indirect inference (1)

We present a novel approach for developing summary statisticsfor use in approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) algorithms byusing indirect inference(...) In the indirect inference approach toABC the parameters of an auxiliary model fitted to the data becomethe summary statistics. Although applicable to any ABC technique,we embed this approach within a sequential Monte Carlo algorithmthat is completely adaptive and requires very little tuning(...)

[Drovandi, Pettitt & Faddy, 2011]

c© Indirect inference provides summary statistics for ABC...

ABC using indirect inference (2)

...the above result shows that, in the limit as h→ 0, ABC willbe more accurate than an indirect inference method whose auxiliarystatistics are the same as the summary statistic that is used forABC(...) Initial analysis showed that which method is moreaccurate depends on the true value of θ.

[Fearnhead and Prangle, 2012]

c© Indirect inference provides estimates rather than global inference...

Genetics of ABC

1 simulation-based methods inEconometrics

2 Genetics of ABC

3 Approximate Bayesian computation

4 ABC for model choice

5 ABC model choice via random forests

6 ABC estimation via random forests

7 [some] asymptotics of ABC

Genetic background of ABC

ABC is a recent computational technique that only requires agenerative model, i.e., being able to sample from the density f (·|θ)

This technique stemmed from population genetics models, about15 years ago, and population geneticists still contributesignificantly to methodological developments of ABC.

[Griffith & al., 1997; Tavare & al., 1999]

Population genetics

[Part derived from the teaching material of Raphael Leblois, ENS Lyon, November 2010]

• Describe the genotypes, estimate the alleles frequencies,determine their distribution among individuals, populationsand between populations;

• Predict and understand the evolution of gene frequencies inpopulations as a result of various factors.

c© Analyses the effect of various evolutive forces (mutation, drift,migration, selection) on the evolution of gene frequencies in timeand space.

Wright-Fisher modelLe modèle de Wright-Fisher

•! En l’absence de mutation et de

sélection, les fréquences

alléliques dérivent (augmentent

et diminuent) inévitablement

jusqu’à la fixation d’un allèle

•! La dérive conduit donc à la

perte de variation génétique à

l’intérieur des populations

• A population of constantsize, in which individualsreproduce at the same time.

• Each gene in a generation isa copy of a gene of theprevious generation.

• In the absence of mutationand selection, allelefrequencies derive inevitablyuntil the fixation of anallele.

Coalescent theory

[Kingman, 1982; Tajima, Tavare, &tc]

5

!"#$%&'(('")**+$,-'".'"/010234%'".'5"*$*%()23$15"6"

!!"7**+$,-'",()5534%'" " "!"7**+$,-'"8",$)('5,'1,'"9"

"":";<;=>7?@<#" " " """"":"ABC7#?@>><#"

"":"D+04%'1,'5" " " """"":"E010)($/3'".'5"/F1'5"

"":"G353$1")&)12"HD$+I)+.J" " """"":"G353$1")++3F+'"HK),LI)+.J"

Coalescence theory interested in the genealogy of a sample ofgenes back in time to the common ancestor of the sample.

Common ancestor

6

Tim

e of

coal

esce

nce

(T)

Modélisation du processus de dérive génétique

en “remontant dans le temps”

jusqu’à l’ancêtre commun d’un échantillon de gènes

Les différentes

lignées fusionnent

(coalescent) au fur et à mesure que

l’on remonte vers le

passé

The different lineages merge when we go back in the past.

Neutral mutations

20

Arbre de coalescence et mutations

Sous l’hypothèse de neutralité des marqueurs génétiques étudiés,

les mutations sont indépendantes de la généalogie

i.e. la généalogie ne dépend que des processus démographiques

On construit donc la généalogie selon les paramètres

démographiques (ex. N),

puis on ajoute a posteriori les

mutations sur les différentes

branches, du MRCA au feuilles de

l’arbre

On obtient ainsi des données de

polymorphisme sous les modèles

démographiques et mutationnels

considérés

• Under the assumption ofneutrality, the mutationsare independent of thegenealogy.

• We construct the genealogyaccording to thedemographic parameters,then we add a posteriori themutations.

Neutral model at a given microsatellite locus, in a closedpanmictic population at equilibrium

Kingman’s genealogyWhen time axis isnormalized,T (k) ∼ Exp(k(k−1)/2)

Mutations according tothe Simple stepwiseMutation Model(SMM)• date of the mutations ∼Poisson process withintensity θ/2 over thebranches• MRCA = 100• independent mutations:±1 with pr. 1/2

Neutral model at a given microsatellite locus, in a closedpanmictic population at equilibrium

Kingman’s genealogyWhen time axis isnormalized,T (k) ∼ Exp(k(k−1)/2)

Mutations according tothe Simple stepwiseMutation Model(SMM)• date of the mutations ∼Poisson process withintensity θ/2 over thebranches

• MRCA = 100• independent mutations:±1 with pr. 1/2

Neutral model at a given microsatellite locus, in a closedpanmictic population at equilibrium

Observations: leafs of the treeθ =?

Kingman’s genealogyWhen time axis isnormalized,T (k) ∼ Exp(k(k−1)/2)

Mutations according tothe Simple stepwiseMutation Model(SMM)• date of the mutations ∼Poisson process withintensity θ/2 over thebranches• MRCA = 100• independent mutations:±1 with pr. 1/2

Much more interesting models. . .

• several independent locusIndependent gene genealogies and mutations

• different populationslinked by an evolutionary scenario made of divergences,admixtures, migrations between populations, selectionpressure, etc.

• larger sample sizeusually between 50 and 100 genes

Available population scenarios

Between populations: three types of events, backward in time

• the divergence is the fusion between two populations,

• the admixture is the split of a population into two parts,

• the migration allows the move of some lineages of apopulation to another.

38 2. Modèles de génétique des populations

•4

•2

•5

•3

•1

Lignée ancestrale

Passé

PrésentT5

T4

T3

T2

MRCA

FIGURE 2.2: Exemple de généalogie de cinq individus issus d’une seule population fermée à l’équilibre. Lesindividus échantillonnés sont représentés par les feuilles du dendrogramme, les durées inter-coalescencesT2, . . . , T5 sont indépendantes, et Tk est de loi exponentielle de paramètre k

�k - 1

�/2.

Pop1 Pop2

Pop1Divergence

(a)

t

t0

Pop1 Pop3 Pop2

Admixture

(b)

1 - rr

t

t0

m12

m21

Pop1 Pop2

Migration

(c)

t

t0

FIGURE 2.3: Représentations graphiques des trois types d’évènements inter-populationnels d’un scénariodémographique. Il existe deux familles d’évènements inter-populationnels. La première famille est simple,elle correspond aux évènement inter-populationnels instantanés. C’est le cas d’une divergence ou d’uneadmixture. (a) Deux populations qui évoluent pour se fusionner dans le cas d’une divergence. (b) Trois po-pulations qui évoluent en parallèle pour une admixture. Pour cette situation, chacun des tubes représente(on peut imaginer qu’il porte à l’intérieur) la généalogie de la population qui évolue indépendamment desautres suivant un coalescent de Kingman.La deuxième correspond à la présence d’une migration.(c) Cette situation est légèrement plus compliquéeque la précédente à cause des flux de gènes (plus d’indépendance). Ici, un seul processus évolutif gouverneles deux populations réunies. La présence de migrations entre les populations Pop1 et Pop2 implique desdéplacements de lignées d’une population à l’autre et ainsi la concurrence entre les évènements de coales-cence et de migration.

A complex scenario

The goal is to discriminate between different population scenariosfrom a dataset of polymorphism (DNA sample) y observed at thepresent time.

2.5 Conclusion 37

Divergence

Pop1

Ne1

Pop4

Ne4

Admixture

Pop3

Ne3

Pop6Ne6

Pop2

Ne2

Pop5Ne5

Migration

m

m0

t = 0

t5

t4

t04Ne4

Ne04

t3

t2

t1r 1 - r

1 - ss

FIGURE 2.1: Exemple d’un scénario évolutif complexe composé d’évènements inter-populationnels. Cescénario implique quatre populations échantillonnées Pop1, . . . , Pop4 et deux autres populations non-observées Pop5 et Pop6. Les branches de ce schéma sont des "tubes" et le scénario démographique contraintla généalogie à rester à l’intérieur de ces "tubes". La migration entre les populations Pop3 et Pop4 sur lapériode [0, t3] est paramétrée par les taux de migration m et m0. Les deux évènements d’admixture sont pa-ramétrés par les dates t1 et t3 ainsi que les taux d’admixture respectifs r et s. Les trois évènements restantssont des divergences, respectivement en t2, t4 et t5. L’événement en t04 correspond à un changement de tailleefficace dans la population Pop4.

Demo-genetic inference

Each model is characterized by a set of parameters θ that coverhistorical (time divergence, admixture time ...), demographics(population sizes, admixture rates, migration rates, ...) and genetic(mutation rate, ...) factors

The goal is to estimate these parameters from a dataset ofpolymorphism (DNA sample) y observed at the present time

Problem: most of the time, we can not calculate the likelihood ofthe polymorphism data f (y|θ).

Untractable likelihood

Missing (too missing!) data structure:

f (y|θ) =

∫

Gf (y|G ,θ)f (G |θ)dG

The genealogies are considered as nuisance parameters.

This problematic thus differs from the phylogenetic approachwhere the tree is the parameter of interesst.

A genuine example of application

94

!""#$%&'()*+,(-*.&(/+0$'"1)()&$/+2!,03 !1/+*%*'"4*+56(""4&7()&$/.+.1#+4*.+8-9':*.+

Pygmies populations: do they have a common origin? Is there alot of exchanges between pygmies and non-pygmies populations?

Scenarios under competition

96

!""#$%&'()*+,(-*.&(/+0$'"1)()&$/+2!,03 !1/+*%*'"4*+56(""4&7()&$/.+.1#+4*.+8-9':*.+

Différents scénarios possibles, choix de scenario par ABC

Verdu et al. 2009

Simulation results

97

!""#$%&'()*+,(-*.&(/+0$'"1)()&$/+2!,03 !1/+*%*'"4*+56(""4&7()&$/.+.1#+4*.+8-9':*.+

Différents scénarios possibles, choix de scenario par ABC

Le scenario 1a est largement soutenu par rapport aux

autres ! plaide pour une origine commune des

populations pygmées d’Afrique de l’Ouest Verdu et al. 2009

97

!""#$%&'()*+,(-*.&(/+0$'"1)()&$/+2!,03 !1/+*%*'"4*+56(""4&7()&$/.+.1#+4*.+8-9':*.+

Différents scénarios possibles, choix de scenario par ABC

Le scenario 1a est largement soutenu par rapport aux

autres ! plaide pour une origine commune des

populations pygmées d’Afrique de l’Ouest Verdu et al. 2009

c© Scenario 1A is chosen.

Most likely scenario

99

!""#$%&'()*+,(-*.&(/+0$'"1)()&$/+2!,03 !1/+*%*'"4*+56(""4&7()&$/.+.1#+4*.+8-9':*.+

Scénario

évolutif :

on « raconte »

une histoire à

partir de ces

inférences

Verdu et al. 2009

Instance of ecological questions [message in a beetle]

• How the Asian Ladybirdbeetle arrived in Europe?

• Why does they swarm rightnow?

• What are the routes ofinvasion?

• How to get rid of them?

• Why did the chicken crossthe road?

[Lombaert & al., 2010, PLoS ONE]beetles in forests

Worldwide invasion routes of Harmonia Axyridis

For each outbreak, the arrow indicates the most likely invasionpathway and the associated posterior probability, with 95% credibleintervals in brackets

[Estoup et al., 2012, Molecular Ecology Res.]

Worldwide invasion routes of Harmonia Axyridis

For each outbreak, the arrow indicates the most likely invasionpathway and the associated posterior probability, with 95% credibleintervals in brackets

[Estoup et al., 2012, Molecular Ecology Res.]

A population genetic illustration of ABC model choice

Two populations (1 and 2) having diverged at a fixed known timein the past and third population (3) which diverged from one ofthose two populations (models 1 and 2, respectively).

Observation of 50 diploid individuals/population genotyped at 5,50 or 100 independent microsatellite loci.

Model 2

A population genetic illustration of ABC model choice

Two populations (1 and 2) having diverged at a fixed known timein the past and third population (3) which diverged from one ofthose two populations (models 1 and 2, respectively).

Observation of 50 diploid individuals/population genotyped at 5,50 or 100 independent microsatellite loci.

Stepwise mutation model: the number of repeats of the mutatedgene increases or decreases by one. Mutation rate µ common to allloci set to 0.005 (single parameter) with uniform prior distribution

µ ∼ U [0.0001, 0.01]

A population genetic illustration of ABC model choice

Summary statistics associated to the (δµ)2 distance

xl ,i ,j repeated number of allele in locus l = 1, . . . , L for individuali = 1, . . . , 100 within the population j = 1, 2, 3. Then

(δµ)2j1,j2 =

1

L

L∑

l=1

1

100

100∑

i1=1

xl ,i1,j1 −1

100

100∑

i2=1

xl ,i2,j2

2

.

A population genetic illustration of ABC model choice

For two copies of locus l with allele sizes xl ,i ,j1 and xl ,i ′,j2 , mostrecent common ancestor at coalescence time τj1,j2 , gene genealogydistance of 2τj1,j2 , hence number of mutations Poisson withparameter 2µτj1,j2 . Therefore,

E{(

xl ,i ,j1 − xl ,i ′,j2)2 |τj1,j2

}= 2µτj1,j2

andModel 1 Model 2

E{

(δµ)21,2

}2µ1t ′ 2µ2t ′

E{

(δµ)21,3

}2µ1t 2µ2t ′

E{

(δµ)22,3

}2µ1t ′ 2µ2t

A population genetic illustration of ABC model choice

Thus,

• Bayes factor based only on distance (δµ)21,2 not convergent: if

µ1 = µ2, same expectation

• Bayes factor based only on distance (δµ)21,3 or (δµ)2

2,3 notconvergent: if µ1 = 2µ2 or 2µ1 = µ2 same expectation

• if two of the three distances are used, Bayes factor converges:there is no (µ1, µ2) for which all expectations are equal

A population genetic illustration of ABC model choice

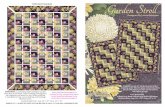

●

● ●

5 50 100

0.0

0.4

0.8

DM2(12)

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

● ●

●

5 50 100

0.0

0.4

0.8

DM2(13)

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●●●●

●

●●●●●●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

5 50 100

0.0

0.4

0.8

DM2(13) & DM2(23)

Posterior probabilities that the data is from model 1 for 5, 50and 100 loci