Aa report

Transcript of Aa report

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting

Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a

Modern Skyscraper

Table of Contents Page

Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………..3

1.0 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………...5

2.0 Critical Regionalism………………………………………………………………………….7

2.1 Introduction to Critical Regionalism……………………………………………….7

2.2 Influence of Critical Regionalism in Malaysia…………………………………..10

3.0 Application of Critical Regionalism in Vertical Developments including the

skyscraper typology………………………………………………………………………..12

4.0 Similarities & Differences between Menara Mesiniaga and Generic Skyscraper…...17

4.1 Menara Mesiniaga As Compared to the International Style…………………..18

4.2 Menara Mesiniaga Similarities to the International Style……………………...18

4.3 Menara Mesiniaga Differences As Compared to the International Style…….19

5.0 Vernacular and Malay Architecture……………………………………………………….22

5.1 Introduction to Vernacular Architecture………………………………………….22

5.2 Characteristics and Adaptation of Vernacular Malay Architecture in a Tropical

Climate……………………………………………………………………………...23

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 1

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

5.3 Adaptation of Malay Architecture’s Bioclimatic Strategies in Menara

Mesiniaga…………………………………………………………………………..28

6.0 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………..32

7.0 References………………………………………………………………………………….33

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 2

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Abstract

In the current age of globalization, architecture seeks to resuscitate local identities

and instil a psychological sense of place and belonging. However, the last thing we need

today is another simple-minded attempt to revive the hypothetical forms of a lost vernacular

or the employment of the International Style in architecture which would only result in

buildings struggling to adapt to the changed environmental or sociocultural context. Hence,

Critical Regionalism; an approach to architecture that strives to adopt Modern Architecture,

critically, for its universal progressive qualities in addition to using geographical contextual

forces to add value and meaning to the architecture, as the former lack sense of place and

significance alone. This research paper aims to discuss Critical Regionalism and its

approach adopted into Ken Yeang’s Menara Mesiniaga. The intention of carrying out this

study is to identify the qualities of Critical Regionalism found in skyscrapers that sets them

apart from the generic skyscraper. It is anticipated that the adaptation of vernacular Malay

architecture form technologies into the building are being discovered through this case

study. Literature reviews from various reliable sources regarding vernacular Malay

architecture and critical regionalism were conducted to further assist in the validation of this

research. In order to provide a wider variation of research, it is important to deliberate on

Critical Regionalist architecture found within the Asian context, in which the Bedok Court

Condominium in Singapore and the Rokko Housing I, II and III in Japan are taken to

understand how the building design and its contextual response exemplifies critical

regionalism. Comparisons between Menara Mesiniaga and the vernacular Malay

architecture were also made to prove that there is a solid relationship between the two

designs. It is understood that vernacular Malay architecture is heavily influenced by climate,

where effective design steps were taken to accommodate the warm and humid climate found

in Malaysia. Moreover, its flexibility in design through an addition system has allowed it to

cater to the widely different needs of users. These qualities could be found in Menara

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 3

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Mesiniaga, therefore strengthening the fact that there are vernacular Malay architecture

influences on the building design such as the building layout, ventilation strategies, shading

and natural lighting. The vernacular influence is further enhanced through the application of

bioclimatic design in the building, where passive design strategies were implemented in

order to achieve thermal and visual comfort as a whole. Hence, this concludes that Menara

Mesiniaga is a critical regionalist architecture, where the building design has not only taken

the vernacular into consideration but has also included the environmental context, ultimately

giving meaning and sense of place to the building.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 4

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

1.0 Introduction

Malaysia, being an equatorial country, experiences a hot and humid climate all year

long, with frequent rains and high temperatures being the norm. The town in which Menara

Mesiniaga is located in, Subang Jaya, is located in the Greater Kuala Lumpur region, known

as the Klang Valley. Subang Jaya is also known to have an abnormally high amount of

lightning strikes in the region, and as such also has a high frequency of rain.

In general, the local architecture typically reflects the need for thermal comfort of its

occupants. While Subang Jaya itself does not have any vernacular or historical architecture

per se, its buildings do have considerations in the form of the 5-foot way (which is a public

shaded road), north facing solar orientation, small windows and clerestories for stack

ventilation. However, the Menara Mesiniaga takes its sustainable practices from more than

these modern practices.

The vernacular architecture of Malaysia could be found in the villages and kampungs

in the form of the Rumah Melayu. While the Rumah Melayu itself is a building topology and

thus many variants exist thereof, there exist general design axioms. The Rumah Melayu

exhibits a multitude of passive design solutions that result in a thermally comfortable internal

environment for its occupants.

For Ken Yeang, three main forces influence his design methodology.

1. The climate. Buildings have to be designed in response to the ambient conditions of

the site, and the design solution ultimately have to be specific to the location. With

equatorial climate of Malaysia, Ken Yeang had to account for heavy rainfall, searing

temperatures and relentless sun in its design. The local conditions of Subang Jaya

also had to be considered, with its winds and other climatic elements influencing the

Menara Mesiniaga’s design.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 5

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

2. The culture. Buildings have to be designed according to the local attitude and way of

life. The Malaysian work ethic, views and priorities have to be accounted for, and

thus will influence the spatial planning as well as facilities and systems.

3. The aspirations of countries to join the developed world.

These forces can be summed up by the fact that there will never be a standard “one-

size fits all” solution in architecture. This is directly contradictory to the “International Style”

philosophy, of which assumes there exists a “universal truth” in architecture, and thus

justifying the existence of the same approach, form and programme regardless if the building

is in New York or in Kuala Lumpur.

The Menara Mesiniaga can be seen as the physical manifestation of this

methodology. Everything from its form, to its spatial planning, to its internal systems proves

that this methodology is clearly influential on the building’s design. Most importantly, it has a

relatively high success in achieving those thermal comfort goals for its occupants.

This paper will investigate the adaptation of vernacular Malay architecture form and

technologies in a modern skyscraper by responding to the following research questions:

Question 1: What is critical regionalism and how does it influence architecture in

Malaysia?

Question 2: How is critical regionalism applied in the skyscraper typology?

Question 3: What are the similarities/differences of critical regionalism used in Menara

Mesiniaga compared to the generic skyscraper?

Question 4: How does the Malay vernacular architecture influence the design of Menara

Mesiniaga?

Question 5: How does the bioclimatic design applied in Menara Mesiniaga parallels the

strategies used in Malay vernacular architecture?

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 6

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

2.0 Critical Regionalism

2.1 Introduction to Critical Regionalism

Critical Regionalism is an approach to architecture that strives to counter the

inauthentic and lack of meaning in Modern Architecture by using contextual means to give a

sense of place and identity. The term was first used by Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre

and later more famously and pretentiously by Kenneth Frampton in “Towards a Critical

Regionalism: Six points of an architecture of resistance.” As per said by Kenneth Frampton,

Critical Regionalism should take up modern architecture critically for its universal

progressive qualities but at the same time should value the responses specifically to the

context. Emphasis should be placed on topography, climate, light, tectonic form rather than

scenography and the tactile sense rather than the visual.

Critical Regionalism vs. Regionalism

As put forth by Tzonis and Lefaivre, critical regionalism need not be directly drawn

from the context, rather elements can be stripped of their context and used in strange rather

than familiar ways. Critical regionalism is distinct from regionalism which attempts to achieve

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 7

Figure 2.1.1 Menara Mesiniaga

(Source: AKDN,n.d)

Figure 2.1.2 Malay Kampung House

(Source: Master thesis "One Straight Story", 2015)

Figure 2.1.3 International Critical Regionalism

(Source: WorldMuseum, n.d)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

a one-to-one correspondence with vernacular architecture in conscious way without

consciously partaking in the universal.

Critical regionalism is considered as a particular form of post-modern (not to be

confused with post-modernism as architectural style) response in developing countries. The

following architects have used such an approach in some of their works: Alvar Aalto, Jorn

Utzon, Studio Granda, Mario Botta, B.V.Doshi, Charles Correa, Alvaro Siza, Rafael Moneo,

Geoffrey Bawa, Raj Rewal, Tadao Ando, Mack Scogin / Merrill Elam, Ken Yeang, William

S.W Lim, Tay Kheag Soon, Juhani Pallasma and Tan Hock Beng.

The architects have to mediate the impact of universal civilization with elements

derived from the peculiarities of a particular space. There are preference to how the architect

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 8

Figure 2.1.5 ISM Apartment Block 1951

(Source: Hilary French: Key Urban Housing of the Twentieth Century, Lawrence King Publishing,

London, 2008)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

deals with the irregularities of the physical landscape rather than how he or she employs

local culture. The architects should enter “a dialectical relation with nature”, taking clues from

topography and avoiding bulldozing in order to flatten space. Using top-lighting and exposing

the elements of construction is a way to express critical regionalism, and it must be speaking

more of the relationship of the building to its space.

Sometimes Regionalism goes back to just conservation and resorts to blind use of

vernacular but critical regionalism seeks architectural traditions that are deeply rooted in the

local conditions. This results in a highly intelligent and appropriate relevant architecture. In

its broadest sense, then, the Critical Regionalist sensibility looks to the uniqueness of site

and location when deriving the formal aspects of any given project.

All point to a design method that is assuredly modern but relies on the organic unity

of local material, climatic and cultural characteristics to lend coherence to the finished work.

The result is an architecture suited light and touch. Through a studied and careful

appreciation of provincial traditions, regionalism in the post-war years resulted in designs

permeate with sensitivity to the specifics of local climates and materials, topographies and

building methods.

In a global aspect, its influence can be felt in the work of the Tichino School in

Switzerland, the sophisticated urban infusions of many contemporary Spanish architects

(including Rafael Moneo), or the austere concrete forms of the Japanese master Tadao

Ando.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 9

Figure 2.1.4 National Museum of Roman Art, Rafael Moneo

(Source: Archdaily, 2015)

Figure 2.2.1 Menara Mesiniaga

(Source: AKDN, n.d.)

Figure 2.2.2 Menara Dayabumi

(Source: Panaromio, 2013)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

The Southern California work of Richard Neutra in the 1930s, for example, or the

brilliant projects designed by the Barcelona architect J.A Coderch, demonstrate a variety of

innovative alterations of local forms and methods to the requirements of modern

functionality. The results are formally and conceptually divorced from received notions of

style, as in the case of Coderch’s celebrated ISM apartment block (1951), which represents

a modern brick veneer mediated by carefully realized interpolations of traditional elements

such as full-height wood shutters and thin overhanging cornices.

2.2 Influence of Critical Regionalism in Malaysia

The influence of critical regionalism is blatantly displayed in Malaysian context, as

there are plenty of skyscrapers imbued with our very vernacular qualities. The architects

Ken Yeang with Menara Mesiniaga, Nik Mohammed with Menara Dayabumi, and Cesar

Pelli with our proud Petronas Twin Tower have appropriately expressed our culture into the

internationally influenced building to create our very own identity.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 10

Figure 2.2.3 Petronas Twin Tower

(Source: Momoc, 2009)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 11

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

3.0 Application of Critical Regionalism in Vertical Developments

including the skyscraper typology

According to Collins English Dictionary (2000), a

skyscraper is defined as a tall building of multiple

stories, especially one for office or commercial use. In

the modern context, the term was coined when Chicago

had one building to first employ the use of steel

structure, which was the Home Insurance Building, built

in 1885. It was a major stepping-stone toward modern

skyscraper construction in the years to come

(History.com, 2010). Today, most skyscrapers are

merely designed to be the tallest and outstanding

structure, thus devoid of sense of contextual identity.

Applying Critical Regionalism in vertical developments especially skyscrapers can be

a tedious process. It involves understanding the context to which the skyscraper would be

built upon, ultimately reflecting locality and contributing to place identity. This is extremely

important as skyscrapers stands as a monumental structure and the intention of applying

critical regionalism approach in skyscraper design will be outstanding as it will definitely

differ from other modernist skyscrapers. Failure to design a skyscraper to respond to both

context and culture will result in the conformation of skyscraper that shows placelessness

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 12

Figure 3.1: Home Insurance Building(Source:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/38/Home_Insurance_Building.JPG)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

and lack of identity, similar to skyscrapers that have adopted the International Style or

Modernism approach.

Two case studies were made to identify how critical regionalism is applied to the

skyscraper typology. The case studies chosen are located in London and Singapore

respectively. This is to show the various approaches these skyscraper designs were made

across different context and climate, displaying critical regionalism.

Case Study 1:

London - 1 Undershaft

By Avery Associates

1 Undershaft (Figure 3.2) is a proposed skyscraper to be built in the financial district

of London, replacing the currently standing St Helen’s building. It is set to be the world’s

exemplary skyscraper in applying Critical Regionalism in its design.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 13

Figure 3.2: 1 Undershaft(Source:

http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/pictures/606x422fitpad[0]/5/5/4/1406554_14-12-16-1-Undershaft-AAA-5.jpg)

Figure 3.3: St. Helen’s building(Source: http://www.e-

architect.co.uk/images/jpgs/london/london_building_aw050507_204.jpg)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

St. Helen’s building as shown in Figure 3.3, is a skyscraper that has applied the

International Style in its design. Due to the site being bought by a different owner, plans

were made to demolish the building and to build a brand new skyscraper

(Skyscrapernews.com, 2015). In result, the proposed design for the new building was made

and has actually succeeded in its design due to its sensitive response to its context.

1 Undershaft is set to be built among the London skyline, standing along notable

skyscrapers such as 30 St Mary Axe (the Gherkin), the Leadenhall building (the

Cheesegrater), The Scalpel and 20 Fenchurch Street (the Walkie-Talkie). Its design is

intended to correlate closely with its surroundings, especially having the lowest possible

visual impact on the skyline (The Angry Architect, 2015).

Note, in Figure 3.4, how the building has its massing responding directly to the

adjacent Leadenhall building and has taken into consideration of not obscuring the view of

the Gherkin (Weston, 2015). The building’s design also pays attention to its climatic

response as shown in Figure 3.5.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 14

1 Undershaft

Leadenhall building20 Fenchurch

30 St Mary Axe

30 St Mary Axe

1 UndershaftLeadenhall building

Figure 3.4: 1 Undershaft among London skyscrapers

(Source: https://acdn.architizer.com/thumbnails-PRODUCTION/68/fc/68fc7df057869e2a2b04776a7311185

5.jpg)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

In short, the prospect of a context-sensitive architecture in the heart of a commercial

business centre has shown that 1 Undershaft design has successfully applied Critical

Regionalism. The building has brought in principles of modernism and has responded to

surrounding formal and cultural factors, allowing it to compete with its surrounding

skyscrapers yet maintaining the sense of place within the London skyline. Although the

proposal fell through in the last minute due to new ownership, it undoubtedly would have

been the first skyscraper in the world to attempt Critical Regionalism in this scale and

context.

Case Study 2:

Singapore – Oasia Hotel Downtown

By WOHA

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 15

Figure 3.5: Section and diagram of 1 Undershaft

(http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=1791935)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Oasia Hotel Downtown is one of the few skyscrapers that eschew the International

Style of a sealed glass box. The building design has taken into consideration its tropical

climate based on its context. The double-skin façade system functions as an environmental

buffer, shading against harsh tropical sun from warming up the hotel rooms and sky terraces

(Figure 3.6). It also visually blurs out the transition between the air-conditioned interior from

the naturally ventilated public space and the building exterior (Furuto, 2012).

WOHA has adopted the club sandwich approach by splitting the building into 3

different strata, each with its own sky garden. This creates generous public areas for

recreation and social interaction within the hotel. The open sky terraces also allows good

cross-ventilation apart from allowing visual transparency, ultimately ensuring thermal comfort

(WOHA, 2016). This way, the hotel has successfully incorporated open, functional and

comfortable public space in contrast with the typical hotel design typology which is enclosed

air conditioned spaces.

In short, Oasia Hotel Downtown was designed to combat the generic, International-

Style skyscraper by creating open spaces throughout the high-rise. The design also caters to

its tropical climate where ventilation is prioritized in order to achieve thermal comfort. Its

unique façade has also stood out among neighbouring skyscrapers in Singapore’s Central

Business District, providing a fresh look to the area.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 16

Figure 3.6: (L-R) Oasia Hotel Downtown among Singapore’s Central Business District, View of Hotel from Gopeng Street, Carved-in skygarden viewed up close.

(Source: http://www.woha.net/#Oasia-Hotel-Downtown)

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

4.0 Similarities & Differences between Menara Mesiniaga and

Generic Skyscraper

The “generic skyscraper” is a misnomer, as it implies there exists a “standard

template” of which all skyscrapers around the world follow. While effectively this may be true,

we first have to understand that the modern stereotype of a skyscraper being a tall, narrow,

glass covered box did have its roots influenced by cultural and climatic situation in the place

where it was first designed.

The problem arises when this climatic and cultural response is assumed to be the

same the world over, and thus the design is exported all over the globe (thus the term,

International Style, a term which was not coined by any of the Modernist architects) with this

very assumption, resulting in the general population assuming that there exists a “generic

skyscraper”.

Thus, we can now define the “generic skyscraper” as a tall, office building built

according to the International Style of architecture, and would then exhibit characteristics

common to it.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 17

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Figure 4.1: Typical characteristics of an International Style skyscraper

(Source: Bill Zbaren, 2015)

4.1 Menara Mesiniaga As Compared to the International

Style

In general, Menara Mesiniaga exhibits the Structural Expressionism style of

architecture, a contemporary approach during its construction period that, as its name

suggests, exhibits its structural systems and expresses it as a part of the building’s form.

This style can be traced back to the Modernist style of architecture, where buildings have a

certain degree of expressing its structure, although it was largely hidden away in the

building’s walls.

However, though Menara Mesiniaga does seem to tick all of the boxes for being an

International Style building, the beauty of the Critical Regionalism approach is that, while it

may have the physical characteristics of an International Style structure, the method and

deployment of these characteristics define the Menara Mesiniaga as a contemporary

example of Asian architecture.

4.2 Menara Mesiniaga Similarities to the International Style

At first glance, the Menara Mesiniaga does seem to have large International Style

influences (unsurprisingly considering its origins). While it may not have a rectilinear form, it

does have a central, cylindrical massing. It has no ornamentations, and has a lot of planar

surfaces. Interior spaces are relatively open, with very little structure obstructing circulation

or views. There is a heavy usage of glass and steel, and cantilever construction could be

found on the ground floor’s foyer.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 18

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Figure 4.2.1: Similarities to the International Style of skyscraper

(Source: Aga Khan Development Network, 1995)

4.3 Menara Mesiniaga Differences As Compared to the

International Style

As discussed in the previous Section (4), the employment of the Critical Regionalist

approach to architecture has resulted in the adoption of vernacular architectural tectonics,

technologies and approaches in the Menara Mesiniaga. This has resulted in the Menara

Mesiniaga displaying the following principle differences:

Figure 4.3.1: Principle differences between Menara Mesiniaga and International Style skyscrapers

(Source: Aga Khan Development Network, 1995)

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 19

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Broken Up Massing

Description: In stark contrast to the smooth homogenous surfaces of the International Style

skyscraper, the Menara Mesiniaga’s smooth cylindrical form is highly punctuated by

apertures that appear to have “penetrated” into the building in an upward, spiralling pattern.

Rationale: This broken-up massing is done for principally for the usage of greenery as well

as introducing permeable interior spaces. Similar to a vernacular Malay house.

Figure 4.3.2: Instead of a smooth, homogenous massing, Menara Mesiniaga has created voids in its

cylindrical form, allowing for the use of passive design elements.

Usage Of Greenery

Description: The usage of vegetation in any building

as a thermal control strategy is concept employed by

the vernacular Malay house. While International Style

skyscrapers seem to be extremely reluctant in the

employment of any vegetation, the Menara Mesiniaga

uses it liberally to cool and shade the interior from the

sun.

Rationale: It can be argued that it is a necessary

approach given its climatic context.

Figure 4.3.3: Use of vegetation in Menara Mesiniaga highlighted

Permeable Spaces

Description: International Style skyscrapers are known to

have relatively airtight environments. In fact, the rise of

sick building syndrome cases can be directly linked to the

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 20

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

increasing use of HVAC in office buildings. Menara Mesiniaga, in contrast, employs the use

of permeable spaces (i.e. allowing outside air to flow inward).

Rationale: This is a form of cross ventilation that is also used by the Malay house, an

effective form of passive design for the climatic situation.

Figure 4.3.4: Wind enters through permeable façade and into the interior, ventilating and cooling the

internal environment.

Emphasis On Sunshading

Description: Menara Mesiniaga is renowned for its

expressed use of large, sun shading louvres that are

hung. This creates a visual depth compared to the

relatively flat surfaces of International Style skyscrapers,

and proves the local context’s importance on the usage

of sunshading devices due to the existing climatic

condition.

Rationale: The local climatic situation requires extensive

sunshading devices to minimize solar gain.

Figure 4.3.5: Large sunshading louvres are expressed

While Menara Mesiniaga already bears a rather obvious difference to the “generic

skyscraper”, it is worth bearing in mind the reasons, rationale and justifications for this. Ken

Yeang did not design Menara Mesiniaga just so he could put Malaysia on a map with its

radical form; rather, it is an exercise in necessity – a design specifically for the given site

conditions.

5.0 Vernacular and Malay Architecture

5.1 Introduction to Vernacular Architecture

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 21

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

According to an analysis by Connor Janzen (2015), in terms of architecture,

vernacular defines the built environment as structures created by untrained individuals,

suited for particular needs of the individual who built the structure. For example, macro

climate of an area is a significant influence on vernacular architecture. In Malaysia, the hot

and humid climate affect the use of low thermal mass materials and application of cross-

ventilation.

Characteristics of vernacular architecture is also governed by local environment and

construction materials. For instance, Malaysia – being covered in rainforest and abundant in

trees and timber as building materials, developed a wooden vernacular. In other words,

vernacular architecture can be seen as designing based on local needs, availability of

construction materials and reflecting local traditions.

Apart from that, the way of life of users and the use of the building heavily influence

the building’s form. Interaction between users and cultural aspects also affect the layout and

size of buildings in vernacular architecture.

Vernacular is meant to be sustainable – thus not exhausting the local resources

available. Unsustainability of the local resources makes it unsuitable for local context, hence

it is not considered as vernacular.

Vernacular architecture in any region creates a connection between both culture and

architecture, and people in the region. Vernacular architecture is not stringently limited to

any specific region, but it is becoming more popular as a design strategy in modern day

urban planning and building.

Vernacular architecture is inclined to develop in order to reflect the environmental,

cultural, technological, economic and historical context. Specifically to Malaysia, some of the

ideals in vernacular architecture include sustainability, cultural significance and adaptability.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 22

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Through understanding and analyzing these ideals, they can be utilized to further improve

schemes and design regarding architecture.

Figure 5.1.1 Example of a Malay House (Yuan, 1987)

5.2 Characteristics and Adaptation of Vernacular Malay

Architecture in a Tropical Climate

Among the characteristics of vernacular Malay architecture is that there is an

extensive comprehension and consideration of nature. As villagers were highly dependent

on nature to provide for their needs, a deep understanding of the study of ecology was

widespread. Their daily necessities including building materials were acquired directly from

nature. The traditional Malay house is designed directly with nature in its approach through

its climatic design. In order to grasp the adaptation of the traditional Malay house, the

environmental conditions of the tropical climate must be understood.

Set up wholly by the villagers themselves, the traditional Malay house is an

outstanding house form which takes the local climatic conditions as well as the social life of

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 23

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

the inhabitants into consideration. It is designed to adapt to the warm and humid climate of

Malaysia as well as for functional purposes. Its flexible design meets the various needs of

the users.

Design for Climatic Control

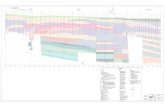

Figure 5.2.1 Climatic Design and Considerations in a Traditional Malay House

The design and form of the traditional Malay house illustrates several characteristics that

equips its house form with the suitability to adapt to the hot and humid climatic conditions in

Malaysia.

(a) Ventilation for passive cooling and humidity control;

(b) Direct solar radiation control;

(c) Control of glare from the surroundings and open sky;

(d) Protection from rain;

(e) Natural vegetation in the surroundings for a cooler environment;

(f) Building materials of low thermal capacity (for minimal heat transmission into the

house

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 24

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

The traditional Malay house is mainly focused on the ventilation and solar radiation control

for the climatic comfort for the inhabitants in the house as these are the effective criteria for

climatic comfort in a hot and humid environment.

Design Approach for Ventilation

Figure 5.2.2: Design Approach for Ventilation in a Traditional Malay House

Ventilation in a traditional Malay house consists of three strategies: top, bottom and

cross ventilation at an appropriate body height. With these approaches, appropriate design

features and adaptive devices are practised.

1. Planning Layout/ Site Planning

Figure 5.2.3: Random Arrangement of Malay Houses

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 25

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

a) Random arrangement of houses

This is to ensure that the wind has a comparatively unrestricted passage through the

community.

b) Orientation

Due to religious purposes, traditional Malay houses are oriented to face Mecca (in an east-

west orientation). This minimises exposure to heat from solar radiation. The direction is also

appropriate for the wind direction in Malaysia (north-east and south-west).

Figure 5.2.4: Ventilation Aided by Raised Floor in a Traditional Malay House

c) Raised Floor

The traditional Malay houses are raised on timber stilts or pile to elevate the building for

natural ventilation as well as a form of protection from floods.

d) Vegetation

The compound of the Malay house is often heavily shaded with trees and covered with

vegetation. This sets the house in a cooler environment as well as reduces glare from the

surrounding environment with the less reflective natural ground covers.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 26

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

2. Building Layout

Figure 5.2.5: Floor Layout of a Traditional Malay House

a) Elongated open plans to allow easy passage of air and good cross ventilation.

b) Minimal partitions for natural lighting and air circulation within the whole interior space.

3. Openings

Figure 5.2.6: Ventilation Openings of a Traditional Malay House

a) Full-length fully openable windows and doors (due to the body level being the most vital

area for ventilation) to achieve cross ventilation. Exterior winds are also encouraged to

ventilate the spaces in the house.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 27

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

b) Decorative elements (intricate carved wooden ventilation grilles and panels – tebar layar)

for air passage through roof area.

4. Roof Elements

a) Ventilation joints and panels in the roof construction (tebar layar) to trap and direct air for

roof ventilation.

b) No ceiling panel to assure no air blockage.

c) Ventilated roof space for cooling of the house.

d) Large overhangs for provision of good protection against heavy rainfall, solar radiation

and to allow for windows to be left open most of the time for ventilation.

e) Construction materials with low thermal capacity for minimal heat retention.

5.3 Adaptation of Malay Architecture’s Bioclimatic

Strategies in Menara Mesiniaga

Bioclimatic high-rise is a skyscraper with designs and spaces which provide passive

low energy benefits. Connections with Malay architecture are evident in the case of the

design of the Menara Mesiniaga. The architect’s intention in taking the Malay sensitivity to

comfort, climate and nature is encapsulated in the building. The principles and technologies

of shading, openness, permeability to air movement, linkages to water and the garden are

abstracted and applied to high-rise office towers. Besides that, an extensive use of natural

ventilation and natural light reflected of open and permeable Malay house forms are

prominent in the building. Menara Mesiniaga has adapted a few of the traditional Malay

house features which have created excellent bioclimatic designs with both internal and

external features to produce a low energy building ideal for the tropical climate.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 28

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

The traditional Malay house is raised up by silts. The space between the ground

and the house is well shaded with minimum blockage by structures. Besides to protect the

building from flash flood, this allows cross ventilation (Figure 5.3.1) to occur in between the

space, creating a cooling effect at the bottom of the house.

The exoskeleton of Menara Mesiniaga has exposed steel and reinforced concrete

structure (Figure 5.3.2) that wraps around the curtain wall to block the sunlight off. It is

useful as a heat sink component and to minimize heat absorption. The sloped berm and

open mezzanine floors (Figure 5.3.3) which circles the circumference of the building allows

air movement underneath the building. This has created a well-shaded and ventilated lobby

entrance without mechanical systems.

The random arrangement of tall trees in the kampong provides shade and also

does not block the flow of winds into the house. With adequate natural vegetation in the

surroundings, this can create a cooler environment of external and internal of the house.

(Figure 5.3.4)

Menara Mesiniaga has stepped terraces (Figure 5.3.5) which can be seen spiralling

up and away from the berm, generating an atrium which not only provides transitional

spaces and natural ventilation but also the planting enhances the shade and increases the

oxygen supply into the building.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 29

Figure 5.3.3Figure 5.3.2Figure 5.3.1

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Besides that, the traditional Malay house has minimum amount of partitions used

to create open interior spaces. This promotes good ventilation throughout the interior

spaces. Body level is the most important area for ventilation, thus full-length fully openable

windows are important in the house. (Figure 5.3.6)

In Menara Mesiniaga, besides reflecting the sun rays, the exposed columns and

beams are open to encourage air circulation within the building. (Figure 5.3.7) Also, all office

floors terraces are provided with full-height sliding glass doors that allow fresh air in.

Internal enclosed rooms are placed as a central core which provides natural lighting and

a good view of the surrounding context around the building.

In traditional Malay house, attap roof is used as thermal insulator and to provide

shade. It has low thermal capacity which holds less heat and cools down at night. (Figure

5.3.8)

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 30

Figure 5.3.5Figure 5.3.4

Figure 5.3.7Figure 5.3.6

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

In Menara Mesiniaga, a cantilevering rooftop pool is designed to ‘green’ the

rooftop by insulating and reflecting the overhead sun. Ken Yeang has also adopted and

implemented the idea by making the central core as extensive passive heating and

cooling strategies (Figure 5.3.9) of the building. The concrete core of the building is

situated on exterior of the east side of the tower. This creates sun shading for the building

and its material construction allows it to become a heat sink that will reradiate absorbed heat

into the interiors at night.

Furthermore, large roof overhang and the low exposed vertical areas (windows and

walls) are essential to traditional Malay Houses to provide protection against driving rain,

good shading and allow the windows to be left open most of the time for ventilation.

In Menara Mesiniaga, the curvilinear overhang roof (Figure 5.3.11) minimises the

south façade from exposing to solar radiation from the high angled sun. On north and south

façade, double-glazed curtain walls are used to control solar gain whereas on the east and

west façade, aluminium fins and louvers (Figure 5.3.12) are installed to provide sun

shading for the interior spaces.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 31

Figure 5.3.9Figure 5.3.8

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

6.0 Conclusion

Critical regionalism is an approach to architecture that seeks to mediate between the

global and the local languages of architecture, in addition to regionalism in vernacular

architecture. The term typically denotes an architecture that is derived from its local setting,

ultimately becoming inherently site specific, while responding to the local climate and culture.

It places emphasis on the reflection of local tradition and culture of a building’s site through

its design and material to prevent the lack of identity and placelessness in the building.

The influence of critical regionalism in skyscraper typology and in the Malaysian

context has significantly affected the design of Menara Mesiniaga, as did the adaptation of

vernacular Malay architecture.

These design approaches and bioclimatic principles implemented were not only

quintessential to make a mark in the world of architecture, but also vital in order to create a

sustainable built form which responds fittingly to the site context.

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 32

Figure 5.3.11Figure 5.3.10 Figure 5.3.12

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

7.0 References

A HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE - CRITICAL REGIONALISM. (n.d.). Retrieved November

25, 2016, from http://www.historiasztuki.com.pl/kodowane/003-02-05-ARCHWSP-

REGIONALIZM-eng.php

Ahmad, A. MALAY VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE. Hbp.usm.my. Retrieved 28 October

2016, from http://www.hbp.usm.my/conservation/malayvernacular.htm

An Architecture of Resistance – Kenneth Frampton (1983). (2011). Retrieved November 27,

2016, from https://criticalregionalismdotcom.wordpress.com/2011/03/03/an-

architecture-of-resistance-kenneth-frampton-1983/

Bromberek, Z. (2004). Contexts of architecture: Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference

of the Architectural Science Association ANZAScA and the International Building

Performance Simulation Association - Australasia, Launceston, 10-12 November,

2004. Retrieved November 20, 2016, from

http://anzasca.net/.../uploads/2014/08/ANZAScA2004_Kamal.pdf

Critical regionalism. (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2016, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_regionalism

Critical Regionalism. Retrieved November 23, 2016, from

http://www.slideshare.net/ar_suryas/critical-regionalism

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 33

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

Furuto, A. (2012). Oasia Downtown / WOHA. ArchDaily. Retrieved 18 November 2016, from

http://www.archdaily.com/215376/oasia-downtown-woha

History.com (2010). Home Insurance Building - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com.

HISTORY.com. Retrieved 14 November 2016, from

http://www.history.com/topics/home-insurance-building

Janzen, C. (2015). Vernacular Architecture in Malaysia – Connor Janzen. Retrieved

November 15, 2016 from http://connorjanzen.com/vernacular-malaysia/

Menara Mesiniaga. (n.d.). Retrieved November 15, 2016, from

http://www.mesiniaga.com.my/about-us/menara-mesiniaga.aspx

Nasir, A. & Teh, H. (1996). The traditional Malay house (1st ed.). Shah Alam: Fajar Bakti.

skyscraper. (2000). Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition.

Retrieved 13 November 2016, from Dictionary.com

website http://www.dictionary.com/browse/skyscraper

Skyscrapernews.com (2015). Avery Associates Aviva Proposals - Article #3508.

Skyscrapernews.com. Retrieved 26 November 2016, from

http://www.skyscrapernews.com/news.php?ref=3508

Surya Ramesh, Architect at Government Engineering College, Thrissur Follow. (2008).

The Angry Architect (2015). Hidden in Plain View: Is This the World’s First Contextual

Skyscraper?. Architizer. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from

http://architizer.com/blog/hidden-in-plain-view/

Weston, R. (2015). The Contextual Tower: Avery Associates' No 1 Undershaft. Architects

Journal. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from

https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/buildings/the-contextual-tower-avery-associates-

no1-undershaft/8674823.article

Wijnen, B. Malay Houses. Malaysiasite.nl. Retrieved 20 October 2016, from

http://www.malaysiasite.nl/malayhouse.htm

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 34

Menara Mesiniaga and Critical Regionalism: Adapting Vernacular Malay Architecture Form and Technologies in a Modern Skyscraper

WOHA (2016). WOHA. Woha.net. Retrieved 18 November 2016, from

http://www.woha.net/#Oasia-Hotel-Downtown

ARC 2213/2234 Asian Architecture 35