A visit to Sarawak and N.W.Borneo in 1845

-

Upload

martin-laverty -

Category

Documents

-

view

97 -

download

2

description

Transcript of A visit to Sarawak and N.W.Borneo in 1845

Bentley's miscellany, Volume 23 (1848) pp 65-72 [also: The eclectic magazine of foreign literature, science, and art, Volume 13

(March 1848) pp416-421 ]

VISIT TO HIS HIGHNESS RAJAH BROOKE,AT SARAWAK1.

BY PETER McQUHAE2,CAPTAIN OF HER MAJESTY's SHIP Daedalus3

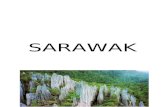

WITH AN ENGRAVING OF THE BUNGALOW OF THE RAJAH4.

On the 18th July, 1845, H.M. squadron, consisting of one line-of-battle ship, two frigates, three brigs, and one steamer, under the command of Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane5, got under weigh, formed order of sailing in two columns, and proceeded to beat down the Straits of Malacca. After several days' sailing, a fierce Sumatra squall was encountered, which brought the squadron in two compact lines to an anchor off the Buffalo rocks in very deep water. Some cause prevented the commander-in-chief from approaching nearer to the town of Singapore. Supplies of bread and water having been brought out by an iron steamer, the Pluto,—Mr. Brooke6, Rajah of Sarawak, and Capt. Bethune7, the commissioners for the affairs of Borneo, having embarked in the flag-ship, a brig of war detached to New Zealand —once more the order of sailing was formed, and the force proceeded down the straits of Singapore en route for Borneo.

That immense, unexplored, and little-known island has, since the occupation of Singapore by the British, as a natural consequence become of daily increasing importance, and the settlement on that fine and navigable river, the Sarawak, under the rajahship of Mr. Brooke, bids fair to produce results, which, even in his most sanguine moments, he could scarcely have anticipated.

It is hardly possible to speak of this gentleman in terms of sufficient force to convey an idea of what has already been accomplished by his talents, courage, perseverance, judgment, and integrity. It required moral courage of a high order, in the face of difficulties to the minds of most men insurmountable, to bring the wild, piratical, and treacherous Malay8, and the still more savage race, the Dyak9 tribes, not only to listen to the voice of reason, but to become amenable to its laws under his government. His perseverance was great under trials, disappointments, and provocations of a nature to damp the energy of the most enthusiastic philanthropist that ever undertook to ameliorate the condition of his fellow man. His judgment has been rarely excelled in discovering the secret motives of the different chiefs with whom his innumerable negotiations had to be conducted ; and in an extraordinary degree he possessed the power of discriminating between the wish to be honest and that to deceive, betray, and plunder. He evinced the most unimpeachable integrity, the most rigid justice in protecting the poor man from the tyranny and exactions of the more powerful chief; and he showed his little kingdom that the administration of law was as inflexible in its operation towards the great men of the country as towards the more humble of his subjects;—and all this he carried into effect by mildness of manner and gentleness of rule.

He has gained the love and affection of many; he has incurred the hatred of some, and is hourly exposed to the sanguinary vengeance of the leaders, whose riches were gathered amidst murder and plunder from the unfortunate crew of some betrayed or shipwrecked vessel, and who have foresight sufficient to perceive that if settlements similar to that on the Sarawak should be extended along the northwest coast of the island, their bloody occupation is gone. They therefore endeavour to hinder, as far as in them lies, the good which is flowing from the noble and brilliant example of his highness the rajah of Sarawak, of whom Great Britain has reason to be proud. It is for the British government to afford that countenance and protection which shall be necessary to prevent the interference of others, who from jealousy may wish by intrigues to interrupt, if not to destroy the great moral lesson now first exhibited amongst these wild people, and in regions hitherto shrouded in the darkest clouds of heathenism and barbarity, amongst a people by whom piracy, murder, and plunder are not considered as crimes, but as the common acts of a profession which their forefathers

followed, which they have been taught to look upon from their earliest days as the only true occupation, in which they may rise according to the number and atrocity of their cruelties.

Not long since several wretches were convicted at Singapore, on the clearest evidence, and condemned to death for deeds of the most revolting and sanguinary barbarity. At the foot of the gallows rather a fine-looking young man, a Malay, justified himself on the principles above stated, and died declaring himself an innocent and very ill-used man, since all he had done was in the regular way of his business. It is not to be wondered at then, that, entertaining such doctrines and sentiments, the whole Malay population of the great and numerous islands of the East, have been regarded by the European commercial world and navigators in these seas as a race of treacherous and blood-thirsty miscreants. How admirable, then, in our countryman to have commenced the good work of regeneration amongst many millions of such men, not by the power of the sword, but by demonstrating practically the eternal and immutable rules of equity and truth!

On the arrival of the squadron off the Sarawak, a party accompanied the admiral in the Pluto to the house and establishment of Mr. Brooke at Kutching10, about eighteen miles above the mouth of the river. The house, although not large, is airy and commodious for the climate, and stands on the left bank of the river on undulating ground of the richest quality, capable of producing in abundance every article common to the tropics; clearance was progressing on both sides of the river, and will doubtless rapidly increase when the perfect security of property which exists is more generally understood and appreciated. Some years ago a small colony of industrious Chinese located themselves on the banks of the river, under the protection of the rajah of the day : their little settlement became flourishing and prosperous, and was rapidly increasing in wealth and importance, when at one fell swoop the villanous Malays seized, plundered, and murdered them; and the more fortunate Chinese who escaped home spread the report of their treatment so widely, that it will take some time to remove the impression. But I feel convinced that emigration from China under British protection might be carried to any extent, and a race truly agricultural and industrious introduced, to the great benefit of this rich but neglected portion of the world. It may be mentioned as a singular fact, that on no part of this coast was the cocoa-nut, that invariable type of a tropical region, found, having been gradually destroyed by pirates, until introduced by Mr. Brooke, who has used every exertion to extend the planting of trees, by having the seedlings brought in great quantities from Singapore ; and by convincing his people that every tree, at the end of a few years, is worth a dollar from the oil it will produce, which meets a ready sale at all times, many thousands have already been planted, and the number is increasing. It is by such small beginnings that the minds of these people must be distracted from the thoughts of robbery and plunder; and it is by practically shewing them that dollars are to be had without the shedding of blood, that the rajah of Sarawak is endeavouring to sow the seeds of industry and of civilization, and step by step to change their ideas, their habits, their hearts. That an all-wise Providence may prosper his undertaking, must be the prayer of those who may have visited his settlement, and who, like myself, have witnessed his disinterested and unceasing thoughts for the peace, happiness, and comfort of the community of which he may truly be designated the "father."

The town of Kutching stands on both sides of the river, here about 200 yards across; the houses are of very slight construction, with open bamboo floors and mat partitions, best adapted for the climate, although those occupied by the Europeans are of a better description, —still of the same material—all raised some feet from the ground to admit a free circulation of air from underneath.

The night passed by the admiral and party was rendered very agreeable by cool refreshing breezes from some high, insulated, granitic11 mountains at a distance in the interior; and even during the day the heat was not unbearable: thermometer Fahr. about 86°. The canoes on the river are of the slightest construction, and are apparently unsafe; yet the passengers crossing the creeks and the river invariably stand up in them,—but woe to the unpractised or unsteady! Accidents, although rare, do sometimes occur, attended with loss of life.

Mr. Brooke had been absent some six or seven weeks when the admiral accompanied him on his

return to the settlement. He was not expected, but the news of his arrival spread with wonderful velocity, and the various chiefs were speedily assembled to greet him with a cordial and hearty welcome. The reunion of the oldest of his swarthy counsellors, as well as of the youngest, who dropped in after dinner had been removed, and took their places on the benches by the sides of the walls, according to their modes, customs, and privileges, together with the naval officers and European civilians, with the rajah in his chair, and two of his most worthy native friends, entitled by birth to the distinction, seated beside him, presented a picture not destitute of interest, certainly of great variety ; for some of the Dyaks, with round heads, high cheek bones, and large jaws, remarkably differing from the Malay race, were there to complete the background. All were most attentively listening to the conversation of the rajah with his Malay neighbours, enjoying a cheroot occasionally given to them by the visitors, and quietly making their own observations. Mr. Williamson, the interpreter, a native of Malacca, who speaks the language as a Malay, had another group around him, eagerly putting questions on the various little subjects interesting to themselves; and without the least approach to obtrusive familiarity, the evening was passed, I dare say, very much to the satisfaction of all parties.

The principal exports, at this period, consist of antimony ore, of great richness, producing 75 per cent, of pure metal. It is found in great quantities, at a distance of ten miles up, in the river and by excavations from the base of some hills, in the manner of washing the mines. It is brought down the river by the natives, carried into a wharf, where it is accurately weighed, and then shipped for Singapore, by the rajah, who pays for the whole brought from the mines a stipulated price per picue12 to the chiefs, who pay the labourers, boatmen, and all other expenses. In former days, his highness the rajah took the lion's share; but the arrangements of Mr. Brooke are on the most liberal scale, his first and only object being to encourage industry, and to shew how greatly the comfort and happiness of all are promoted by a rigid and just appreciation of the rights of property, and by a faithful and honourable adherence to every agreement and bargain. The result has been a vast increase in the quantity of ore exported, and an extending desire to be interested in the business.

A passing visit does not enable one to speak geologically of a country; and as there is a gentleman of practical science at present making his observations13, it would be presumptuous in me to offer a remark on the formations of this great country. But a single glance at the beautifully undulating hills, at the gorgeous verdure, and growth of every branch of the vegetable kingdom, at once points out the inexhaustible capabilities of the soil for the cultivation of sugar, coffee, spices, and every fruit of the tropics, many of which already flourish as specimens in the rajah's garden and grounds, and invite the industrious to avail themselves of such a country and of such a river, and become proprietors on the banks of the Sarawak. British capital and protection and Chinese Coolies, would very soon change the north and north-west coast of Borneo into one of the richest countries in the world.

The admiral proceeded in the morning some short distance up the river to return the visit of the chiefs, and was every where received with the royal salute of three guns; the whole party, accompanied by the rajah and Mr. Williamson, the interpreter, at eleven A.M. re-embarked on board the Pluto, which had been in a very hazardous situation during the night, having unfortunately grounded on a ledge of rocks close to the bank14, by which she sustained considerable damage; and proceeded down the river to regain the squadron at anchor off Tanjay Po, the western part of the Maratabes branch of the Sarawak; and here it was found that the steamer must be laid on the beach, as it was with difficulty the whole power of the engines applied to the pumps could keep her afloat; she was accordingly placed on the mud flat at the entrance of the river. A frigate and another steamer were left behind to assist in her refit, and the admiral moved onwards towards Borneo Proper15, where, in the course of a few days, all were re-assembled, but in consequence of the flag-ship, by mistaking the channel, having struck the ground on the Moarno shore in going in, the ships were moved outwards some considerable distance. Mr. Brooke, accompanied by an officer from the Agincourt, visited the sultan at the city of Bruni; and, on the following day, the sultan's nephew, heir-presumptive to the throne, with a suite of some twelve or fifteen Pangeran and chiefs of the

blood-royal, under the "yellow canopy," came down to return the compliment, and to communicate with the admiral on affairs of state; they were received with every mark of distinction and kindness by the commander-in-chief, and certainly there never was exhibited a more perfect sample of innate nobility and natural good manners, than was presented by Buddruden, to the observation of those who had the pleasure of witnessing his reception on the quarter deck of a British ship of the line by a crowd of officers, and amidst the noise and smoke of a salute; the whole of this party were the intimate friends of Mr. Brooke and firmly attached to British interests. Buddruden, in reply to some question to him as to his ever having seen so large a ship before, said that, although descended from a very ancient and long line of ancestors, he had the proud satisfaction of being the first who had ever embarked on board a vessel of such wonderful magnitude and power, and so much beyond any idea he had formed of a ship of war. The most marked attention was paid by those who accompanied him to the privileges and etiquette of the country; none below a certain rank presuming to sit down in his highness's presence; indeed, only those indisputably of the blood-royal were admitted to that honour; every part of the ship was visited, and the prahu, with the yellow umbrella-shaped canopy, once more received her royal party, who proceeded to render an account of their visit to the sultan in his regal palace at Bruni, accompanied by the Pluto steamer.

On the following morning, the admiral hoisted his flag on board the Vixen, and, accompanied by the Pluto and Nemesis, also steamers, and taking with him a considerable force of seamen and marines, and an armed boat from each ship, proceeded up the river, with the intention of compelling Pangeran Yussuff to return to his obedience and duty to the sultan, and to give an account of himself for being implicated in piratical transactions.

On the arrival of the armament opposite the town, the sultan held a grand levee for the reception, and in honour of the admiral's visit, and the Pangeran was summoned to present himself in submission to the mandate of the sultan. This he refused to do, and had even the hardihood to approach the palace, and when at last threatened to have his house blown about his ears, coolly answered, that the ships might begin to fire whenever they pleased, that he was ready for them; and sure enough, on the Vixen firing a sixty-eight pounder over his house to show the fellow how completely he was at the mercy of the squadron, he fired his guns in return. A few rounds from the steamers drove him from his bamboo fortress. The marines took possession, and his magazine was emptied of its contents of gunpowder, which was started into the river, and all his brass guns were delivered over to the sultan, with the exception of two, which were retained, to be sold for the benefit of two Manilla Spaniards, who had been piratically seized as slaves, and who were now taken on board the squadron to be restored to their home. His house being thrown open to the tender mercies of his countrymen, was speedily gutted of all his ill-gotten wealth, and left in desolation. There were no killed or wounded. Pangeran Yussuff retreated to the interior, continued in rebellion, raised a force with which he attacked the town and Muda Hassim's party, but was defeated, pursued, and killed by Pangeran Buddruden.

The squadron proceeded to Labooan16, cut wood with the thermometer at 92', for the steamers, filled them; and on the morning of the 15th of August, a new order of sailing and battle was given out per "buntin," and the novelty of two frigates towing two steamers, was exhibited to the wondering eyes of those present, called upon to keep their appointed station, work to windward, tack in succession, and perform every evolution with the neatest precision, in spite of light winds, heavy squalls, and most variable weather.

The force intended to attack the stockade and fortified port of that arch-pirate Scherriff Posman on the Malloodoo River, proceeded under the immediate command of the admiral, who took the brigs and steamers with him to the entrance of the river, and here it was found that the iron steamers, which had caused such trouble, were not of the slightest use, there not being water sufficient even for them over the bar. The whole flotilla was placed under the command of Captain Talbot, of the Vesta, the senior captain present, who, on the morning of the 19th of August, attacked with great gallantry, and carried the very strong position of the pirates, with the loss of eight killed and thirteen wounded. The iron ordnance was broken, the fortification destroyed, and the town

burned to the ground. It was reported the day after the action, that the Arab chief had been mortally wounded, but the squadron quitted the bay before this was confirmed.

I cannot leave Borneo without giving a brief description of the coast from the mouth of the Sarawak to this splendid bay, more particularly as its features are so widely different from those generally attributed to it. From the Sarawak to Tanjong Sirik, the land is low, and for some miles from the beach covered with mangrove jungle, but from that point to Borneo river, undulating ground, moderate hills, and occasionally red-sand cliffs, mark the nature of the country to be dry and susceptible of cultivation ; and, as these hills are clothed in perpetual verdure, there is nothing imaginary in the supposition that the soil is salubrious and productive. From Borneo river, north-eastward, a range of hills, of considerable altitude, run the whole length of the coast, the sea, the greater part of the line, washing their base; and immediately inland, in latitude 6°, that most magnificent and striking of all eastern mountains, Keeney Balloo, towers to the heavens to the height of 14,000 feet, cutting the clear grey sky before sunrise with a sharp distinctness never exceeded, and marking the primitive nature of its formation beyond controversy. It may be called an “island mountain," for, with the exception of the range of hills above alluded to, and with which it has no continuity, it rises abruptly from the plain, alone in its glory, and giant of the eastern stars—

“With meteor standard to the breeze unfurl'd, Looks from his throne of squalls o'er half the world.17"

The Bay of Malloodoo is extensive, with safe anchorage every where; the coast-range of hills terminates on its western shores, and round to the south-east the land is of moderate height, with a range of greater altitude at some distance inland, and Keeney Balloo bounds the view at about thirty-five miles distance in the south-west, The land on the eastern side is low, but on the whole a more eligible position to plant and protect a settlement is not to be found on the whole coast, and it stands so pre-eminently superior to Labooan or Balambargan18, and would so effectually destroy piracy in the neighbouring seas, that the British government ought to have no hesitation in taking possession of this bay, with sufficient breadth of territory to secure supplies and support for a colony. It is quite evident, from the manner in which this pirate Arab has held possession with impunity, and, from his stronghold, had carried on his depredations for years, either that the Sultan of Borneo acted in collusion with him, and was a willing witness to his atrocities, or that he had not the power to clear his territory of such a miscreant. I have no doubt of the former being the case, as much of the property acquired by blood and rapine has frequently been sold publicly in Borneo; perhaps some of it is to be found in the palace of the sultan. There ought to be no delicacy in this matter. Great Britain's claim to the country is scarcely disputed. One well fortified post would, with the presence of a brig-of-war or two, secure the obedience of the whole district. As for Balambargan, it is an arid, sandy island, with scanty supply of water, and an unproductive soil. It has two harbours, both small and intricate, and must always depend upon foreign supply for its sustenance. Labooan may be somewhat better, but its geographical position is not eligible as a station for vessels of war intended to suppress piracy, being too far to leeward in the north-east monsoon, and too distant from the Sooloo seas and adjacent straits, now much frequented by the numerous vessels trading to China, to afford them that protection which a settlement at Malloodoo would at once accomplish. Merchant vessels using the Palawan passage from India and the Straits of Malacca, would find in Malloodoo Bay, during the strength of the north-east monsoon, a wide and extensive anchorage in which to take temporary shelter, and make any refit which might become necessary from working against the monsoon, as well as easy access, equally convenient for vessels taking the Balabac Straits, coming from thence and Macassar.

Stone may be had in abundance in any part of the bay; excellent stone-cutters from Hong Kong in any numbers might be procured, and Coolies in thousands would be found to accompany them. A week's run thence, in the north-east monsoon, would land a wing of a Madras regiment on the ground, and a few junks would convey all the living and dead material necessary to place them in comfort and security in a very short time. The climate is good, the land is rich, and water abundant; the countless acres would soon attract the industry of the Chinese, when once assured of protection

to their lives, and undisturbed possession of their property.

The admiral, accompanied by the Borneo Commissioners, went over on board the Vixen steamer, to the island Balambargan, on the afternoon of the 21st, and the ships of the squadron followed in the course of the night, taking up their anchorage outside the shoals of the southern, whilst the commander-in-chief and his party went to the northern harbours, where the Pluto had preceded them, and at day-dawn on the 22nd, they landed to explore the neighbouring jungle, for the site of the settlement which had been formed by the East India Company in 1773, from which they had been driven by the Sooloo people, but which had been occupied a second time in 1803, and evacuated ultimately as a useless and unprofitable settlement. The British government have always maintained their clear right to this island, ceded to them by the King of Sooloo, on his being liberated from prison at Manilla, when that city was taken by Sir William Draper19; and Balambargan is indisputably a British island, and part of the empire.

The position which the town had occupied was clearly traced by the rubbish, and brick, and mortar, scattered over a considerable surface, and the numerous broken scraps of crockery and glass gave sufficient evidence that here had been placed the houses, buildings, and defences erected by the settlers, but all are now silent and forlorn. In this dry season the soil was completely covered with sand, and the bush of a very scanty growth ; nor could any indications of water be discovered. A long walk on the beach, in the direction of the southern harbour, led to no farther discovery than that some ridges of clay crossed the island, terminating at the shore in moderate altitude, and covered with trees of considerably larger dimensions than those near the site of the town. A complete detour of the harbour was made by the Pluto, from the paddle-boxes of which, the surrounding country being almost level with the sea, could be clearly distinguished as of the same sandy nature, but which, in all probability, is in the rainy season, a lagoon entirely covered with water. It had a poor and uninviting appearance. Several large baboons20 came to the beach, and, taking up their seat on some fallen trunk of a tree, gazed with great tranquillity at the Pluto as she passed along. Many tracks of the wild hog were seen on the beach, but on the whole, Balambargan is the last island I should select as my "Barataria21."

A short visit was made to the adjacent island of Bangney22, and a boat went up a river on the south-west quarter, running for several miles through low, flat, mangrove jungle, but descending in clear cascades from the hilly part of the island, which ranges entirely along the north-western division, and terminates at the north point in a very remarkable and beautiful conical peak, 2000 feet high, covered to the apex with evergreen wood. The south-eastern division is flat, and probably of the same mangrove jungle through which the boat ascended the river, after having with difficulty got over a flat bar at its entrance. On this expedition not a living animal was seen, not even a bird, but the elevated part of Bangney presented a far more inviting aspect than anything to be seen in Balambargan. True, there is no harbour, and, with the exception of the river alluded to, it is said to want water. The piratical prahus sometimes rendezvous here, in readiness to pounce on any unwary vessel passing through the Balabac Straits.

Let me express a hope that the British government will speedily alter the face of affairs in these seas, by supporting Mr. Brooke on the Sarawak, and, without loss of time, planting a similar colony on the shores of the bay of Malloodoo23.

1 This article actually summarises most of the events recounted in other publications :Keppel, (1846) Expedition to Borneo of HMS Dido for the Suppression of Piracy Vol2 Ch XXIIMundy, (1848) Narrative of Events in Borneo and the Celebes down to the Occupation of Labuan Vol2 Ch XXII

Transcribed and annotated by Martin Laverty, Oct 2009; Apr, Jun 20102 Peter McQuhae, or M'Quhae, had been in the Royal Navy since 1803, rising to Captain in 1835 (ref). His chief

claim to fame seems to have arisen on the return voyage to England from the East Indies when a giant sea serpent was spotted between the Cape of Good Hope and St Helena. (Reports in The Times of 9 and 13 October, 1848, summarised by Gosse. in 1860)

3 HMS Daedalus was launched in 1826 as a 46 gun frigate but was reduced to 20 guns in 1840. It sailed for the East Indies in October 1844 (ref)

4 The engraving is by Hugh Low (1824-1905) who had arrived in Sarawak in 1844 to collect plants for his father's nursery in London. It also appeared in his book, Sarawak: its Inhabitants and Productions (1848), and is the only one of the illustrations which he contributed; most were by Hiram Williams (ref 13, below), or unattributed.

The boat may be the Brooke's trading schooner, Julia, in which Low arrived in Sarawak on 14th January 1845, having left Singapore on the 6th. (The Royalist, the schooner yacht which Brooke brought from England - and intended to return in - seems to have been sold by early 1844).

5 Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane (1789-1872) had breaks in his naval career to be Governor of Newfoundland (1832-1834) and MP for Ipswich (1839-1841). He .was cousin of his namesake [the 'Sea-wolf', who had fought the French in the Royal Navy, the Spanish in the Chilean Navy, the Portuguese in the Brazilian Navy, and the Turks in the Greek Navy].

6 James Brooke , (1803-1868) had first visited Sarawak in 18397 Charles Ramsay Drinkwater Bethune (1802-1884) joined the navy in 1815 and rose to Captain in 1830 (ref). 8 Malays were generally coastal people professing Islam. The noble elite often claimed Arab ancestry9 Dyak was the general term for the indigenous natives of Borneo, generally living along the rivers inland and subject

to Malay authority for external trade.10 Kutching, or Kuching, is the main settlement in Sarawak.11 The mountains seen from Kuching are actually a variously of sandstone (Serapi, Matang) to the west, limestone to

the south, and porphyry (Serembu) to the south-west. The first geological map was produced by Hiram Williams in 1845 and published by Captain Rodney Mundy in 1848

12 Picue, actually picul – the standard load for a human carrier in the east: more formally, 133 1/3lbs.13 Hiram Williams (1816-1872) was a land and mineral surveyor from Swansea. He was sent out by the Admiralty to

assist Captain Bethune. He supplied illustrations for Hugh Low's book, as well as some included in JA St.John's Views in the Eastern Archipelago, and a one of Mr. Brooke's House (misattributed in the first edition) plus a chapter on geology for Mundy. On 29th Jan, 1848, he acquired a deed granting him a substantial part of the land Kuching now occupies [Mining Journal, 5 Feb 1848 p101] but seems to have lost interest (perhaps associated with his brother David's death from fever in India later in 1848) and devoted the rest of his life to mining interests in England before becoming a gentleman farmer in Oswestry.

14 The Pluto was not the only ship to ground at Kuching: Belcher's Samarang had grounded in 1843.15 Borneo Proper, ie Brunei town, now Bandar Seri Begawan 16 Labooan, or Labuan17 Quotation from “Pleasures of Hope” by Thomas Campbell 18 Balambargan, or Balambangan, had been settled by the East India Company, but abandoned.19 William Draper (1721-1787)20 As baboons are African rather than Asian apes, the reference is probably to proboscis monkeys.21 Barataria was a fictional island awarded to Don Quixote in the novel by Cervantes.22 Bangney, or Banguey, or Banggi, is the larger island east of Balambangan, and also guarding Maludu Bay.23 British governments were reluctant to grant formal support to Sarawak, but eventually made it a protectorate in

1888, after James Brooke had tried, in despair, to gain support from Belgium and France instead; the only colony they set up was the tiny island of Labuan, in 1847, primarily for its supposedly rich coal deposits; Maludu Bay became part of the country owned by the British North Borneo Company and has never had any major settlement.