A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the · leans on a deck that touches down...

Transcript of A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the · leans on a deck that touches down...

A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the conversation on nature-respecting modern mountain architecture and communal living on Powder Mountain, where an enigmatic group of entrepreneurs, creatives, and altruists is building a pioneering alpine village.

Words by Sandra Henderson Photos by Marshall Birnbaum

Utopia Utahan

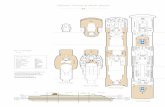

Architecture renders by Srđan Nađ

058 — 059

“We bought a mountain.”

So begins the backstory of Summit Powder Mountain, a visionary colony of cabins and an alpine village being dreamed up in Utah's Wasatch Mountains.

Behind the idea is Summit, an event business started by Elliott Bisnow, a founding board member of the United Nations Foundation’s Global Entrepreneurs Council. What began as a small gathering of a few dozen inves-tors, business whiz kids, and creatives over a short few years grew into the Summit Series: traveling invitational events that summon hundreds of thought leaders and different-thinkers from around the world. "What would it look like if Davos and Burning Man had a baby?" The Guardian rhetorically wondered in a recent article about the Summit Series. For its latest flagship event, Summit at Sea, 2,500 chosen attendees boarded a cruise ship in Miami for a four-day conference in international waters.

Now Summit is building a permanent base camp for its forums—a high-alpine town for its growing tribe to come home to. Summit purchased Powder Mountain, including the ski resort that has been operating there since the 1970s, with the vision to fundamentally reimagine and experi-ment with how people live together, shelter themselves, and converge for the greater good. “I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world,” says Summit design director Sam Arthur, who moved to Utah to see the project through. Since buying the mountain in 2013, Summit has called on sundry architecture and design gurus, even sacred geometry to conceive this test bed for communal living. But the group still needed a cohesive cabin concept, a trademark design that considers the demands of living at 8,400 feet (2,560 meters) altitude, of building sensibly on historically mostly undeveloped, pristine mountain land that includes an elk reserve, natural waterways, and thriving wildlife. A sheep ranch was the only settlement on the mountain for the longest time.

Right: Design competition winner Srđan Nađ wanted to create a cabin concept that can be enlarged, scaled down, rearranged, or have a different facade and still preserve the overall design idea.

Thus, Summit’s Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition challenged the global guild of archi-tects, engineers, artists—masters and students alike—to design sustainable cabins that embody the leadership’s ideals of sustainability, use of natural materials, and humble expression. The winning concept would guide the architectural ethos for more than 500 single-family homes, limited to 2,500 square feet (232 square meters) on half- to two-acre lots. Arthur says they capped the size of the homes so Summit Powder Mountain could become a democratized, harmonious environment for the community at large rather than “this über-wealthy place that is about showing off how big and bad you are.” Larger lots of up to thirty acres, however, could potentially accommodate a compound design.

The winner: Srđan Nađ, a young architect from Slovenia. His prized design was inspired by a Summit event photo he had seen—a green meadow dotted with simple white tents, pure architecture integrated within thin cloth, pitched to create shelter from weather and wilderness. His other muse was the frontier cabin of America’s past, a simple wooden structure with a great stone chimney on the out-side. “Combining both was my design concept for Summit Powder Mountain—a true connection with nature,” says Nađ, who believes “95 percent luck” won him the compe-tition. More likely, though, he convinced the international jury panel, led by Todd Saunders of Saunders Architecture (Norway) and Jenny Wu from the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles, California), with his design’s adaptability and transformational potential. Arthur says, “Srđan did a beautiful job of meeting the criteria and applying a certain amount of aesthetic to it that really eloquently resolved that future/nostalgia-heritage/modern friction, which is at the core of what people respond to here, how they want to live in the modern age.” With its indoor/outdoor quality and what Arthur describes as “an obsession with light and views,” Nađ’s design captures the raison d’être for living on a mountain. “It’s a place to find refuge, to be inspired, to take in the natural primary source of beauty, and recreate with friends. It’s often very difficult to turn

“I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world.”

060 — 061

“When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective.”

Above: Summit purchased Utah's Powder Mountain in 2013 with the vision to build an experimental resort town there but also to preserve the surrounding untouched wilderness.

062 — 063

that into architecture, but Srđan took that and wrapped a building around it.”

Born to two architects in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1983, Nađ’s career choice was perhaps destined by birth. He attended a special building and engineering high school and spent his senior year abroad in upstate New York. He returned to Europe to study architecture at the University of Ljubljana, which he describes as a “boutique school” in the center of the city. “I had the opportunity to do a lot of architectural competitions and really test my ideas—and, of course, learn from my mistakes.” After practicing the craft with other studios for several years, Nađ founded Grupo H with his wife, a landscape architect. Based in Slovenia and surrounded by mountains and the outdoors, the company is dedicated equally to architecture and interdisciplinary aspects of planning and building.

“I grew up in Dubrovnik, Croatia, a great historic town by the Adriatic Sea, so I didn't have any understanding of the alpine world until my fantastic wife, a local Slovenian girl, introduced me to the alpine world of Slovenia and its natural environment,” Nađ says. “What’s special about Slo-venia is that the mountains here are relatively inaccessible, and to get to know them, you need to hike a lot. Hiking is a local obsession here.”

Living in the small European country known for its moun-tains, outdoor recreation, and ski resorts—much like Utah—has transformed the man from the seaside. “When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective,” says Nađ. “It teaches you to admire and respect the wild nature of the alpine world. In the end, when you are put into the position to design a building for such a surrounding, all your knowledge and memories come together to create this unique combina-tion of simplicity and elegance that a building high in the mountains demands.“

His proposed cabin design preserves that tentlike lightness and unmistakable functionality that inspired him and

“You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.”

manifests it in a permanent, habitable structure. The archi-tect expresses this lightness through a 1.5-inch (3.80-cm) thin “skin” made from cross-laminated prefabricated wood panels, folded to create the interior space of the cabin. This folding process leaves open the sides, which are then covered in glass. Juxtaposing the transient openness of the folded skin, a monolithic stone chimney stakes the raised cabin, grounding it into the mountainside to create the permanence a tent lacks. The chimney’s body also houses the mechanicals. On the opposite side, the cabin leans on a deck that touches down to the ground. With only the chimney and the deck as supporting elements, the cabin’s footprint is small, making large earth excavations unnecessary. The triple-glazed glass walls let the sun heat the highly insulated interior. Rainwater from the sloping roof collects into storage tanks under the deck. The goal is for the cabins to be certified according to the European passive house standard and the American LEED standard.

The cabin design allows for different versions of the prototype, varying from a simple one-bedroom hut to a luxurious four-bedroom chalet. The blueprint foresees an open living/dining/kitchen area with a large fireplace. The high ceiling follows the geometry of the exterior roof, mimicking the surrounding mountain silhouette. “In all, it will be a fantastic place to come back to after a full day of skiing or a long summer hike,” the architect hopes.

Nađ’s minimalistic “wooden tents” are designed to serve as fully functional habitable structures without creating the feel of urban settlement on Powder Mountain, and they preserve the essence of the natural surroundings. Nađ strove to convey the notion of living in nature rather than intruding upon the alpine landscape to stake out your private piece of paradise.

His sensible solution was, no doubt, spawned by his home country and culture. “We are really humble, hardworking, and resourceful people. So that guides me to find simple, functional, and long-lasting designs for my projects,” he says, adding that the alpine cabins and shelters of the Slovenian mountains influenced his “wooden tents” for

Nađ’s “wooden tents” convey the notion of living in nature rather than intruding upon the alpine landscape to stake out one's private piece of paradise.

064 — 065

Summit Powder Mountain. “They are simple, rugged, but still graceful in unforgiving nature.”

Nađ didn’t plan to enter an architecture contest at the time he learned about the MAP design competition on an archi-tecture blog. But the subject—a cabin—intrigued him since he thought it rather uncommon for an international con-test. “You usually have a competition to design a museum, library, memorials...but houses are rare.” The premise of Summit Powder Mountain eventually compelled the young architect to enter his design. “You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.” However, he didn’t grasp the expanse of the project until he spoke with the Summit team. “I didn’t realize how important this is for the global community, as it shows a new way of planning large developments,” he says in retrospect. Nađ understood that no matter how good his cabin design was going to be, simply copying it 500 times would only create the type of cookie-cutter development that already char-acterizes too many mountain resort towns. “My design goal was to create a house that can be transformed—enlarged, scaled down, rearranged, have a different facade—and still preserve the overall design idea,” he explains. The

“wooden tent” concept is a suggestion, one Arthur says is “a loose design that’s poetic and evocative.”

Summit hopes to break ground in the summer. Fifteen to twenty people have already committed to building a cabin on Powder Mountain. Furthermore, the company is planning the new alpine village, with shops and galleries, coffeehouses and restaurants, gathering venues, condos, and new headquarters for the ski resort they acquired. Arthur thinks seasonal skiers and hikers may visit the mountain and never know about Summit’s quest for set-tling an art, culture, and tech elite here, though it seems hard to imagine tourists coming to this creation of an idyll and doing their own thing. “We’re based on gathering,” Arthur emphasizes. “People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

In fact, Arthur argues that the encouraged culture of sharing is just another expression of Summit’s tacit broader understanding of sustainable living. “This isn’t ostentatious.” He points out that most members of the Summit Powder Mountain community would actually prefer to minimize their footprint by operating in a shared social space. “Rather than building large bathrooms and kitchens in their own house, people go home to sleep and to entertain a smaller group of people. Then they go out into the larger community spaces and venues to gather together. This is about collectivism and collaboration.”

But how do you curate a genial commune where strangers “gather in creativity” to become kindred spirits, collabo-rators, neighbors? You don’t. “We had a blunt policy for a while, a ‘no-asshole policy,’ ” Arthur reveals. In reality, they quickly came to understand that the Summit community fosters a quite self-selecting environment. “Basically, if you were obviously egocentric or self-centered, then you probably don’t belong here. People who want to par-ticipate and are ‘others-orientated’ and have the heart to expand goodness, usually work out pretty well,” he says. To the rest, it just doesn’t feel right to be there. The Summit leadership strives to strike a balance between public atmosphere and private, curated events. In the end, Arthur says, “It’s not an exclusive membership thing—it’s an overall public realm of creating a new mountain town.”

“People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

What does new mountain architecture look like, act like, feel like? Only after winning did the architect from Slovenia realize how important his design was forthe global community.

066 — 067