A SIGN IS WHAT?

-

Upload

czem-nhobl -

Category

Documents

-

view

237 -

download

0

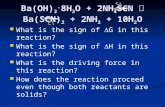

Transcript of A SIGN IS WHAT?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

1/66

A Dramatic Reading in Tree Voices:_________________________________________________________

A Sign is What ?

A D IALOGUE BETWEEN A SEMIOTIST AND A W OULD -BE REALIST

Originally presented as the Presidential Address to the Semiotic Society of Americaat the Friday luncheon of the 26th Annual Meeting

held at Victoria University of the University of orontooronto, Ontario, Canada

October 19, 2001; rst published without line numbers in

Sign Systems Studies 29.2 (2001), 705743artu University, Estonia

Here reprinted fromTe American Journal of Semiotics 20.14 (2004), 166

for the occasion of a live reading based on the textdirected by Professor Charles Krohn

in Jones Hall of the University of St Tomas, Houstonthe Saturday evening of 18 October 2008, 20:4522:00 hoursas part of the 1619 October 2008 33rd Annual Meeting

of the Semiotic Society of America

John DeelyUniversity of St. Tomas, Houston

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

2/66

T he rst voice in this dialogue is the semiotist, commenting tohimself on the overall situation as the discussion moves along.Te second voice belongs to an acquaintance who fancies him-self a thorough-going philosophical realist, and who interrogates thesemiotist on the whole matter of signs. Te third voice is the outerspeech of the semiotist responding to the questions, interjections,and comments the realist makes as the dialogue unfolds.

Tus:

Voice 1 = the inner discourse of the semiotist

Voice 2 = the outer speech of the realist

Voice 3 = the outer speech of the semiotist

Voices 1 and 3 are so marked in the text, while Voice 2 could besimply marked R , since confusion is diffi cult or impossibleto explain so far as such thinkers are concerned.

2

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

3/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 3

123456789

1011121314151617181920

2122232425262728

2930313233343536

37383940

S , inner voice(= Voice 1):

R (= Voice 2):

S , outer voice(= Voice 3):

Voice 1:

Voice 3:

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

Everyone knows that some days are better than oth-ers. I was having one of those other days, when acolleague approached me to express interest in theforthcoming Annual Meeting the 26th, as it hap-pened of the Semiotic Society of America.

Come on. ell me something about this semioticsbusiness.

Whats there to say?

I said, not in the mood for this at the moment.

Semiotics is the study of the action of signs, signsand sign systems.

I knew it would not help to say that semiotics is thestudy of semiosis. So I let it go at that. But inwardlyI cringed, for I could see the question coming like anoffshore tidal wave.

Well, what do you mean by a sign?

Who in semiotics has not gotten this question fromcolleagues a hundred times? In a way it is an easyquestion, for everyone knows what a sign is. Howelse would they know what to look for when drivingto Austin? All you have to do is play on that, and turn

the conversation elsewhere.Maybe it was a change in mood. Maybe it was thefact that I liked this particular colleague. Or maybe Iwanted to playadvocatus diaboli. Whatever the reason,I decided not to take the easy way out, not to playon the common sense understanding of sign which,useful as it is and not exactly wrong, nonetheless ob-scures more than it reveals, and likely as not makes

the inquirer cynical (if he or she is not such already)about this new science of signs.You know the routine. Someone asks you what

a sign is. You respond, You know. Anything that

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

4/66

4 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

4142434445464748495051525354555657585960

6162636465666768

6970717273747576

777879

Voice 3:

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

V 1:

draws your attention to something else. Somethingthat represents another. And they say, You meanlike a traffi c sign? And you say Sure. Or a word. Oa billboard. Anything. And they say, Oh. I think get it. And life goes on.

But this time I decided to go against the grain, andto actually say what I thought a sign was. So I lookemy colleague in the eye for a few moments, and nalsaid , not averting my gaze in the least:

OK. Ill tell you what a sign is. A sign is what eveobject presupposes.

My colleagues eyes widened a bit, the face took onslightly taken-aback expression, and my ears detectean incredulous tone in the words of reply:

A sign iswhat?

What every object presupposes. Something presup

posed by every object.

What do you mean? Could you explain that?

Te colleague seemed serious, and I had no pressingobligations or plans for the moment, so I said

Sure, but lets go outside.

I opened my offi ce door and indicated the stone tabland bench at my disposal in the private fenced areat the end of the driveway that comes to the outerdoor of my offi ce.

My colleague had no way of knowing, but in myprivate semiosis of that moment I could only recalthe SSA Presidential Address given some seventeen

years previously by Tomas A. Sebeok, wherein hecompared the relations of semiotics to the idealistmovement with the case of the giant rat of Sumatra,1

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

5/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 5

8081828384858687888990919293949596979899

100101102103104105106107

108109110111112113114115

116117118

a story for which, as Sherlock Holmes announced,the world is not yet prepared.

In that memorable speech, Sebeok had takenthe occasion to indulge in personal reminiscences,comment on the institutionalization of our commoncultural concerns, and then to prognosticate aboutthe direction toward which we may be headed.2 Now, some seventeen years later, this mantle of SSAPresident had fallen to me; and the institutional sta-tus of semiotics in the university world, healthy andpromising as Sebeok then spoke, had in Americanacademe become somewhat unhealthy and parlousin the succeeding years, even as the interest in andpromise of the intellectual enterprise of semioticshad succeeded beyond what any of us in the 80scould have predicted in the matter of the contest asto whether the general conception of sign study shouldbe conceived on the model of Saussurean semiologyor (picking up the threads and pieces in this matterleft by the teachers common to Peirce and Poinsot3)

Peircean semiotics.4It is true enough that I was in a position, as an as-sociate of Sebeoks since the late 60s, and particularlyas the only living SSA member who had personallyattended every Executive Board meeting since thefounding of the Society in 1976 (and before that inthe 1975 preparatory meeting 5), to indulge in personalreminiscences illuminating how this passage from

promising to parlous had been wrought, but the exer-cise would only be for my expectant colleague acrossthe stone table hugely beside the point of anythingreasonably to be expected in the present discussion.Far better, I thought, to imitate the example set byPhaedrus the Myrrhinusian in responding to Eryxi-machus the Physician at the symposium in the Houseof Agathon. Te present occasion called for nothing

less than a furthering of the abductive assignmentthat our then-elected medicine man proposed asthe main mission of semiotics: to mediate between

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

6/66

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

7/66

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

8/66

8 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216

217218219220221222223224

225226227228229230231232

233234235

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

Voice 3:

No. From here, that is the only sign as such thatappears.

Ah so,

I said.

But in your preliminary inventory you concludedby asking how I had managed such a setup for myoffi ce. So what you saw around you, even before yomisidentied the sign for the building, led you to thinkof something not actually present in our perceptionhere, namely, my offi ce.

What do you mean? Your offi ce is right there (poining to nearest door).

o be sure. But for that door to appear to you asDeelys offi ce door presupposes that you know abomy offi ce; and it is that knowledge, inside your ver

head, I dare say, that presents to you a particular doorwhich could in fact lead to most anything, as leadinin fact to my offi ce. So one door at least, among thosyou noted in this side of the building, even thoughyou did not inventory it as a sign, nonetheless, functioned for you as a sign of my offi ce (the offi ce, afall, which cannot be perceived from here, being aobject which is other than the door which indeed is

here perceived).I see what you mean. So any particular thing whicleads to thought of another may be called a sign.

Perhaps,

I said,

but not so fast. ell me rst what is the differencebetween that former Monaghan House sign and my

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

9/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 9

236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255

256257258259260261262263

264265266267268269270271

272273274

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

offi ce door, insofar as both of them function in yoursemiosis as representations of what is other thanthemselves?

Function in my semiosis?

Forgive my presumption in bringing in so novela term. Semiosis is a word Peirce was inspired tocoin in the context of work connected with his JohnsHopkins logic seminar of 1883,8 from his readingin particular of the 1st century bc Herculaneanpapyrus surviving from the hand (or at least themind) of Philodemus the Epicurean.9 Cognizant nodoubt of the reliable scholastic adage that action iscoextensive with being,10 in the sense that a beingmust act in order to develop or even maintain itsbeing, with the consequent that we are able to knowany being only as and insofar as we become awareof its activity, Peirce considered that we need a termto designate the activity distinctive of the sign in its

proper being as sign, and for this he suggested thecoinage semiosis. So whenever in your own mindone thought leads to another, it is proper to speakof an action of signs, that is to say, of a function ofsemiosis private to you, of the way signs work, theassociations that occur, if you like, in your particularsemiosis. In fact, the whole of your experiential lifecan be represented as a spiral of semiosis, wherein

through the action of signs you make a guess (orabduction), develop its consequences (deduction),and test it in interactions (retroduction), leadingto further guesses, consequences, and tests, andso on, until your particular semiosis comes to anend. So

and here I sketched for him on a scrap of paper

a Semiotic Spiral representing our conscious life asanimals:

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

10/66

10 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294

295296297298299300301302

303304305306307308309310

311312313

continued, Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Te Semiotic Spiral, where A = abduction, B= deduction, C = retroduction

Now my colleague is remarkable in a number of wayone of which is in possessing an excellent knowledof Greek. So I was horried but not surprised whenmy colleague expostulated:

Aha! An excellent coinage, this semiosis, thougperhaps it should include an e between m and i! probably you know that the ancient Greek term forsign is preciselyshmeivon.

Horried was I, for not having expected so soon tobe confronted with what is surely one of the mostincredible tales the contemporary development ofsemiotics has had to tell. It was my turn to deal withthe tangled web of a private semiosis, my experiencin particular on learning through my assignment toteam-teach a course with Umberto Eco,11 that therein fact was no term for a general notion of sign amon

the Greeks. I remember vividly my own increduliton rst hearing this claim. On the face of it, the claimis incredible, as any reader of translations of ancienGreek writings from the Renaissance on can testifyAt the same time, the credibility of Eco as a speakeon the subject equalled or surpassed the incredibilityof the claim. Te evidence for the claim has sincebeen developed considerably,12 and I have been forced

to deem it now more true than incredible. But howshould such a conviction be briey communicated ta colleague, particularly one more knowledgeable o

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

11/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 11

314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333

334335336337338339340341

342343344345346347348349

350351352

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

R :

Greek than I?Tere was nothing for it.

Not exactly so. In truth the termshmeivon in the Greekage does not translate into sign as that term functionsin semiotics, even though the modern translations ofGreek into, say, English, obscure the point. For the termshmeivon in ancient Greek names only one species ofthe things we would single out today as signs, the speciesof what has been called, after Augustine,signa naturalia,natural signs.13

Looking perplexed, my colleague avowed:

I am not so sure that is true. Are you trying to tell methat the word sign as semioticians commonly employit has a direct etymology, philosophically speaking,that goes back only to the the 4th or 5th centuryad? And to Latin, at that, rather than to Greek? oAugustinessignum rather than to theshmeivon of

ancient Greece? Surely you jest?

Te situation is worse than that,

I admitted.

I am trying to tell you that the term sign, as it hascome to signify in semiotics, strictly speaking does not

refer to or designate anything of the sort that you canperceive sensibly or point out with your nger, evenwhile saying Tere is a sign.

Flashing me a glance in equal proportions vexed andincredulous, my colleague said:

Look. I wasnt born yesterday. We point out signs all

the time, and we specically look for them. Drivingto Austin, I watch for signs that tell me I am on theright road, and what exit I should take. Surely you

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

12/66

12 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367368369370371372

373374375376377378379380

381382383384385386387388

389390391

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

dont gainsay that?

Surely not.

I sighed.

Surely not. But semioticians, following rst Poinsot14 and, more recently, Peirce,15 are becoming ac-customed to a hard distinction,16 that between signsin the strict or technical sense and signs loosely ocommonly speaking, which are not signs but elements so related to at least two other elements thatthe unreecting observer can hardly help but takethem as signs among other objects which, at leascomparatively speaking, are not signs. Let me explainthe distinction.

Please.

Te giant rat of Sumatra was veritably on the table,

a problem in a culture for which rats are not consid-ered palatable; a problem compounded by my ownsituation in a subculture about as not yet prepared toentertain considerations of idealism as the world wain the time of Sherlock Holmes to consider the case othe very giant rat now sitting, beady-eyed, on the tablbetween me and my colleague. Fortunately for me, ounfortunately for my colleague, it happened that the

stare of those beady eyes was not xed upon me, sit could not unnerve me so long as I kept control omy imagination.

Now you must consider, in order to appreciatethe turn our conversation takes at this point, that thedepartment in which I teach is affi liated with a Centefor Tomistic Studies, and probably you know thatthe late modern followers of Tomas Aquinas pride

themselves on realism, a philosophical position thholds for the ability of the human mind to knowthings as they are in themselves, prior to or apart from

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

13/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 13

392393394395396397398399400401402403404405406407408409410411

412413414415416417418419

420421422423424425426427

428429430

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

any relation they may have to us. o refute idealism,these fellows generally deem it suffi cient to affi rm theirown position, and let it go at that, their puzzlementbeing conned to understanding how anyone couldthink otherwise.17

But semiotics cannot be reduced to any suchposition as a traditional philosophical realism, evenif Peirce be right in holding (as I think he is right18)that scholastic realism is essential to if not suffi cientfor understanding the action of signs. In other words,the conversation had come to such a pass that, in orderto enable my companion to understand why everyobject of experience as such presupposes the sign,I had to bring him to understand the postmodernpoint enunciated by Heidegger to the effect that19 as compared with realism, idealism, no matter howcontrary and untenable it may be in its results, hasan advantage in principle, provided that it does notmisunderstand itself as psychological idealism. BestI thought, to begin at the beginning.

You would agree, would you not

I put forward my initial tentative

that we can take it as reliable knowledge that theuniverse is older than our earth, and our earth olderthan the life upon it?

So? my colleague reasonably inquired.

So we need to consider that consciousness, humanconsciousness in particular, is not an initial datumbut one that needs to be regarded as something thatemerged in time, time being understood20 simply asthe measure of the motions of the interacting bodies

in space that enables us to say, for example, that somefourteen billion years ago there was an initial explosionout of which came the whole of the universe as we know

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

14/66

14 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

431432433434435436437438439440441442443444445446447448449450

451452453454455456457458

459460461462463464465466

467468469

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

it, though initially bereft of life, indeed, of stars and oplanets on which life could exist.

Surely youre not just going to give me that evolutiostuff? And what has that got to do with signs beingsomething that objects presuppose, a propositionthat doesnt exactly leap out at you as true, or even aparticularly sensible?

Actually it is not evolution, but something more basithat I have in mind. I want to suggest that semiosis imore basic than evolution, and perhaps explainsbetter what has heretofore been termed evolution.21 But, Iadmit, that is a bit much to ask at this point. Perhapsindeed I cast my net too wide. Let me trim my sails bit, and ask you to agree only to this much: there is difference in principle between something that existin our awareness and something that exists whetheror not we are aware of it?

What are you getting at?

A distinction between objects and things, whereinby object I mean something existing as knownsomething existing in my awareness, and by thinrather something that exists whether or not I haveany awareness of it.

But surely you do not deny that one and the samething may be one time unknown and another timeknown? Tis is merely an accident of time, an occur-rence of chance, hardly a distinction in principle.

Ah so. But surely you do not deny that an object oexperience as such necessarily involves a relation me in experiencing it, whereas a thing in the envi

ronment of which I have no awareness lacks such relation?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

15/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 15

470471472473474475476477478479480481482483484485486487488489

490491492493494495496497

498499500501502503504505

506507508

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Well anyone can see that.

And surely you concede that an object of experienceneed not be a thing in the same sense that it is anobject?

What do you mean in saying that?

Consider the witches22 of Salem.

Tere were no witches at Salem.

Ten what did we burn?

Innocent women.

Innocent of what?

Of being witches.

But the people at Salem who burned these women23 thought they were burning witches.

Tey were wrong.

So you say. But surely you see that, if the burnerswere wrong, something that did exist was burnedbecause of something that did not exist? Surely you

see that something public, something objective in mysense the being of a witch was confused withsomething that did exist the being of a female hu-man organism and that something existing wasburned precisely because it was objectively identiedwith something that did not exist?

I think I am beginning to see what you are getting at;

but what does this have to do with signs?Every mistake involves taking something that is not

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

16/66

16 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

509510511512513514515516517518519520521522523524525526527528

529530531532533534535536

537538539540541542543544

545546547

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

for something that is, I said.

rue enough, said my colleague.

So every mistake involves an action of signs.

Yes, I see that to see a witch you have to be mistakebut to see a woman you only need eyes, not signs. It the truth I am interested in. By your account, all thatsigns account for is the possibility of being mistakeWhat about the possibility of being right? Are you arealist or arent you?

If you grant me that an object necessarily, whereaa thing only contingently, involves a relation to mas cognizant, then, in order to advance my argumenthat every object presupposes sign, I need to ask yoto consider the further distinction between sensationand perception, where by the former I understandthe stimulation of my nervous system by the physi

cal surroundings and by the latter I understand theinterpretation of those stimuli according to whichthey present to me something to be sought (+),something to be avoided (), or something aboutwhich I am indifferent ().

I see no problem with that.

Ten perhaps you will grant further that, whereassensation so construed always and necessarily involvme in physical relations that are also objective in thetermini, perception, by contrast, insofar as it assimilates sensation to itself, necessarily involves physicrelations that are also objective, but further involveme in objective relations that may or may not be physcal, especially insofar as I may be mistaken about wh

I perceive. In other words, sensations give me the rawmaterial out of which perception constructs what arefor me objects of experience, such that these object

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

17/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 17

548549550551552553554555556557558559560561562563564565566567

568569570571572573574575

576577578579580581582583

584585586

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

have their being precisely as a network of relationsonly some of which are relations independently of theworkings of my mind and which relations are whichis not something self-evident, but something thatneeds to be sorted out over the course of experienceinsofar as experience becomes human experience.

Why do you say insofar as it becomes human ex-perience?

Because, for reasons we can go into but which hereI may perhaps ask you to assume for purposes ofadvancing the point under discussion, the notion ofa difference between objects and thingsnever occurs toany other animal except those of our own species.

Huh?

Well, youre a realist, arent you?

Of course.

What do you mean by that?

Simple. Tat the objects we experience have a beingindependent of our experience of them.

But you just admitted that we experience objects

which are not things.Yeah, when we make mistakes.

But not only when we make mistakes.

How do you gure?

Is there a boundary between exas and Okla-homa?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

18/66

18 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

587588589590591592593594595596597598599600601602603604605606

607608609610611612613614

615616617618619620621622

623624625

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Is the Pope Catholic?

I take that to be a Yes.

I let pass that the Pope at the moment was Polish:transeat majorem.

Of course there is a boundary between exas andOklahoma. Im no Okie.

But look at the satellite photographs. No suchboundary shows up there. Would you say that theboundary exists objectively rather than physically, bunonetheless really?

Tats a funny way of talking.

Not as funny as thinking that social or cultural realities, whether involving error or not, exist inside youhead as mere psychological states. Consider that wha

sensations you have depends not only on your physical surroundings but just as much upon your bodilytype. Consider further that how you organize yoursensations depends even more upon your biologicaheredity than it does upon the physical surroundingsIf you see that, then you should be able to realize thathe world of experience, not the physical environmenas such, is what is properly called the objective worl

and you cannot avoid further realizing that the objective world of every species is species-specic.

Species-specic objective worlds? I thought the ob jective world was the world that is the same for everbody and everything, the world of what really is.

On the contrary, the world that is the same regardles

of your species is merely the physical environment,and it is, moreover, a species-specifically humahypothesis rather than anything directly perceived

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

19/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 19

626627628629630631632633634635636637638639640641642643644645

646647648649650651652653

654655656657658659660661

662663664

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Because sensation directly and necessarily puts us incontact with the surroundings in precisely somethingof their physical aspect of things obtaining indepen-dently of us, we can from within experience conductexperiments which enable us to distinguish within ourexperience between aspects of the world which existphysically as well as objectively and aspects which existonly objectively. Tat, my friend, is why realism is aphilosophical problem, not a self-evident truth. Afterall, reality is a word, and needs to be learned like anyother. You need to read something 24 of Peirce.

You seem to be veering into idealism.

My colleague frowned mightily, hardly in sign ofapproval.

Not at all. I thought you liked to acknowledge whatis? And certainly an objective world shot throughwith emotions and the possibilities of error, which is

specic to humans and even subspecic to differentpopulations of humans is the reality we experience,not just some physical environment indifferent toour feelings about it? Te indifferent physical envi-ronment is a hypothetical construct, a well-foundedguess, which science conrms in some particularsand disproves in others. For surely you dont thinkit was science or philosophy that disproved witches,

do you? Havent you read the old papal decrees onthe subject, or the theological treatises on how todiscriminate between ordinary women and womenwho are witches?25 It behooves you to do so if you aremarried or even ave a girlfriend.

But all you are talking about is mistakes we havemade, psychological states disconnected from

objectivity.On the contrary, there are no such thing as psycho-

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

20/66

20 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

665666667668669670671672673674675676677678679680681682683684

685686687688689690691692

693694695696697698699700

701702703

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

logical states disconnected from objectivity. Objectiv-ity precisely depends upon psychological states whicgive the subjective foundation or ground for the relations which terminate in the publically experiencedinterpretations that are precisely what we call objectsTe key to the whole thing is relation in its uniquebeing as irreducible to its subjective source alwayterminating at something over and above the beingin which the relation is grounded.

I could not help but think of the two main texts inPoinsot26 which had so long ago rst directed myattention to this simple point made quasi-occultover the course of philosophys history by the obtusdiscussions of relation after Aristotle.27

But I thought knowledge consisted in our assimilation of the form of things without their matter.

Now I knew for sure my colleague was indeed a clos

Tomist at least, versed in the more common Neotho-mist version of ideogenesis, or theory of the formatioof ideas through a process of abstraction.

Well,

I ventured.

In the rst place, that is not a self-evident proposition, but one highly specic medieval theory of thprocess of abstraction; and further, absent the contexof a full-blown theory of relations as suprasubjectivlinks28 to what is objectively other than ourselves withall our psychological states, affective as well as cogtive, such a theory is nally incoherent. For any formwith or without matter, if and insofar as it is in me

part and parcel of my subjectivity, except and insofaas it mayhap gives rise to a relation to something oveand above my subjectivity, which is by denition wh

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

21/66

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

22/66

22 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

743744745746747748749750751752753754755756757758759760761762

763764765766767768769770

771772773774775776777778

779780781

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :S , Voice 3:

it will be a thing as well as an object. Subjectivity, ycan see, is what denes things as things. Objectivityby contrast, obtains only in and through relations,normally a whole network of relations, which give evthe things of the physical environment their status asexperienced and whatever meaning they have for thlifeform experiencing them. Since objectivity alwayincludes (through sensation) something of the sub- jectivity of things in the environment, this objectivmeaning is normally never wholly divorced from thsubjective reality of the physical world, but it is nevreducible to that reality either.

Surely you are not saying that every object is merethe terminus of some relation?

Exactly so some relation or complex of relationa semiotic web, as we like to say in semiotics. Excyour use of merely here seems hardly appropriatwhen one considers that the terminus of cognitive and

affective relations normally involves something of thsubjectivity of things in their aspects as known, evethough the terminus of every relation as terminusowes its being as correlate to the fundament to thesuprasubjectivity distinctive of the being peculiar tand denitive of relation.

And where does sign come in?

At the foundation, my friend; but notas the founda-tion. Tat was the mistake the scholastics made31 intrying to divide signs into formal and instrumentsigns without realizing that our psychological stateare no less particulars than are physical objects wpoint to when we single something out as a sign.

You are losing me.Go back to theshmeivon. Consider the howl of a

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

23/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 23

782783784785786787788789790791792793794795796797798799800801

802803804805806807808809

810811812813814815816817

818819820

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

wolf. Would that be ashmeivon?

My colleague pondered, consulting within the pri-vacy of self-semiosis a knowledge of ancient Greek. Iawaited the result of this consultation.

I am not so sure. Teshmeivon were always sensibleevents, to be sure, and ones deemed natural at that.But they were primarily associated, as I remember,with divination, wherein the natural event mani-fested a will of the gods or a destined fate, or withmedicine, wherein the natural event is a symptomenabling prognosis or diagnosis of health or sickness.No, I am not so sure the howl of a wolf would fallundersov hmi;eivboi>niv, or at least I dont see howit would.

All right then,

I suggested.

Let us consider the howl of a wolf rst just as aphysical event in the environment, a sound or set ofvibrations of a certain wavelength propagating overa nite distance from its source within the physicalsurroundings.

I see no diffi culty in that.

Now let us suppose two organisms endowed withappropriate organs of what we call hearing, situatedwithin the range of propogation of that sound. Whatwould you suppose?

I would suppose they would hear the sound, if theyare not asleep or too distracted.

Let us suppose they hear the sound, the one organ-ism being a sheep and the other another wolf. Now

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

24/66

24 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

821822823824825826827828829830831832833834835836837838839840

841842843844845846847848

849850851852853854855856

857858859

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

the sound occurring physically and subjectively in thenvironment independently of our organisms hearing of it enters into a relation with each of the twoorganisms. Te sound not only exists physically, it nowexists also objectively, for it is heard, it is somethinof which the organisms are respectively aware. It iskind of object, but what kind? For the sheep it is anobject of repulsion (), something inspiring fear andan urge to hide or ee. For the other wolf, a male wolit happens heeding the advice of St. Tomas to usesexual examples to make something memorable leus say that the howl reveals a female in heat. Such sound, no different in its physical subjectivity fromthe vibrations reaching the frightened sheep, inspirein the male an attraction, as it were (+), what formerPresident Carter might call lust in the heart.

What are you saying?

Tat one and the same thing occurring in the en-

vironment gives rise in awareness to quite differenobjects for different organisms, depending on theibiological types. Sensations become incorporated intperceptions of objects not merely according to whathings are in the surroundings but especially according to how the sensations are interrelated within theexperience of the perceiving animal as part of its totobjective world.

So this is what you meant when you said that objective worlds are species-specic?

Exactly so. Every organism in its body is one subjetivity among others, a thing interacting physically witother things in the environment. But if the organismis a cognitive organism, its body has specialized par

suited to a psychological as well as a physiologicresponse to those physical environmental aspectsproportioned to the organ of sense. Te psychological

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

25/66

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

26/66

26 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

899900901902903904905906907908909910911912913914915916917918

919920921922923924925926

927928929930931932933934

935936937

R :

S , Voice 1:

V 3

R :

S , Voice 1:

Voice 3:

Tis is troubling.

I offered,

Let me put you at ease. In order for an organism to baware of something outside itself, there must be insiditself a disposition or state on the basis of which it irelated cognitively (and, I would add, affectively32) tothat outside other. If the outside other has an existenceof its own quite independent of the cognition of thecognizing organism, then it is a thing, indeed. But insofar as it becomes known it is an object, the terminuof a relation founded upon the psychological stateinside the organism. Neither the relation nor the thingbecome object are inside the knower. All that is insidthe knower is the disposition or state presupposedfor the thing to exist as known.33 And the relation isinside neither the knower nor the known but is overand above both of them. Compared to the subjectiv-ity of either the knower or the known the relation

as such is suprasubjective. But as related cognitiveto the knower the thing known is the terminus of arelation founded in the knowers own subjectivityAs terminating the relation it is an object. Tat sameobject if and insofar as it has a subjective being of iown is not merely an object but also a thing.

But what if the object has no subjectivity prope

to it?My colleague probed, thinking, as I suspected fromhis nonverbal signs, of Salem and witches.

Ten it is only an object, what the scholastic realistsused to call a mind-dependent being.34 So do pay at-tention: every mind-dependent being is an objectiv

reality or being, but not every objective reality is mind-dependent being. Some objects are also thingsin which case they are mind-independent beings35 as

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

27/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 27

938939940941942943944945946947948949950951952953954955956957

958959960961962963964965

966967968969970971972973

974975976

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

well as objective realities.

But I thought anens rationis, what you call a mind-dependent being, was a mere mental reality, a psycho-logical state like error or delusion.

Hardly. Surely you recall that, according to the scho-lastic realists so beloved of Peirce, logical entities all areentia rationis? And the relations of logic are supremelypublic, binding upon all? Now it is true that logicreveals to us only the consequences of our beliefs, ofour thinking that things are this way or that, not neces-sarily how things are in their independent being. Butthe fact that logical relations are public realities, notprivate ones, that logical relations revealinescapable consequences of this or that belief, not private whims,already tells you that they belong to the Umwelt, notto the Innenwelt, and to the Umwelt as species-speci-cally human at that.

Umwelt? Innenwelt? Where does that come from?

Sorry. Umwelt is shorthand for objective world. Inthe case of the species-specically human objectiveworld it is often called rather a Lebenswelt; but please,I pleaded, let us not get into that particular right nowor we will never get to the bottom of the question youhave raised as to why a sign is best dened at this stage

of history as what every object presupposes.But,

my colleague interjected,

why in the world do you speak of the denition we areseeking to plumb as best at this stage of history? Surely

you know that a real denition tells what something is,and is not subject to time? Are species not eternal?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

28/66

28 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

977978979980981982983984985986987988989990991992993994995996

997998999

10001001100210031004

10051006100710081009101010111012

101310141015

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

Surely you will allow for more subtlety than that aregards denitions?

I replied hopefully.

After all, even when we try to express in words whthing is, it is our understanding of the thing that weexpress, not purely and simply the thing itself? Andthis is true even when and to the extent that ourunderstanding actually has some overlap, identity, ocoincidence with the being of the thing even whenthat is to say, our denition partially expresses a thinobjectied, a thing made object or known?

I see what you mean. Even a denition supposed reexpresses only our best understanding of some aspecof real being, and insofar as this understanding is noexhaustive it may admit of revision or of being supplanted through subsequent advances or alterationsof understanding, my colleague allowed.

I am glad you see that, for, in the case of the signthere have been at least three, or even more (depending on how you parse the history) revisions of thedenitory formula generally accepted,36 and I expectmore to come.

Dont discourage me, my colleague pleaded. Let

at least get clear for now about this new formula yodeem best at our present historical moment. I geyour meaning of Umwelt. What about this Innenweltbusiness?

Innenwelt is merely shorthand for the complexus opsychological powers and states whereby an organism represents to itself or models the environmen

insofar as it experiences the world. So Innenwelt ithe subjective or private counterpart to the objectiveworld of public experience comprising for any speci

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

29/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 29

10161017101810191020102110221023102410251026102710281029103010311032103310341035

10361037103810391040104110421043

10441045104610471048104910501051

105210531054

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

its Umwelt.

Tat helps, but I fail to see what all this new terminol-ogy and idiosyncratic way of looking at things has todo with signs, let alone with signs being presupposedto objects.

Ten let me introduce at this point the great dis-covery of semiotics, actually rst made in the 16thcentury, or early in the 17th at the latest,37 althoughnever fully marked terminologically until Peirceresumed the Latin discussion around the dawn ofthe 20th century.38 Signs are not particular thingsof any kind but strictly and essentially relations of acertain kind, specically, relations irreducibly triadicin character.

But surely you are not denying thatthat,

my colleague said, pointing to the physical structure

renaming the building beside us as Sullivan ratherthan Monaghan,

is a sign?

No, I am not exactly denying that; what I am denyingis that what makes what you are pointing to a sign isanything about it that you can point to and directly

see with your eyes or touch with your hands. Whatmakes it a sign is that, within your Umwelt, it standsfor something other than itself; and because itsucceeds (in your Umwelt) in so standing it is for you a sign. Butwhat makes it thus succeed is the position it occupies in atriadic relation; and, strictly speaking, it is that relationas a whole that is the being of sign, not any one element,subjective or objective, within the relation.

I dont understand,

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

30/66

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

31/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 31

10941095109610971098109911001101110211031104110511061107110811091110111111121113

11141115111611171118111911201121

11221123112411251126112711281129

113011311132

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

to me as necessary.

A second revision?

Yes. If you will recall,renvoi for Jakobson was notmerely the relation of sign to signed, insofar dyadic,as you have suggested.Renvoi was a relationshipwherein the so-called sign manifested its signicateto or for someone or something. So the formula infact not only needs to be so revised as to preclude thetypically modern epistemological paradigm whereinsigns as other-representations can be confused withobjects as self-representations, as I manifested in my1993 Sebeok Fellowship inaugural address, it needsalso to be revised to include a Latin dative expressingthe indirect reference to the effect wherein an actionof signs achieves it distinctive outcome.

You raise two questions in my mind.

My colleague here with spoke some agitation.

You say that the sign manifests to or for someone orsomething. How is to equivalent with for? And howis someone equivalent with something? But beforeyou respond to these two queries, please, tell me howwould you have the classic formula nally read.

Aliquid alicuique stans pro alio, one thing represent-ing another than itself to yet another , although theimpersonal verb formstat would work as well as theparticipialstans. Only with a nal revision like thiscould it be said nally, as Sebeok said (as I now see)a little prematurely,43 that by the termrenvoi Jakobsonhad deftly captured and transxed each and every signprocess conforming to the classic formula; for if a rela-

tion is not triadic, it is not a sign relation. Whence thetruly classic formula: Aliquid stat alicuique pro alio.

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

32/66

32 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

11331134113511361137113811391140114111421143114411451146114711481149115011511152

11531154115511561157115811591160

11611162116311641165116611671168

116911701171

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

Very interesting,

my colleague allowed that much.

Now could you answer my two questions?

Your questions cut to the heart of the matter. Con-sider the bone of a dinosaur which is known as such.It functions in the awareness of the paleontologist aa sign. He recognizes it, let us say, as the bone of aApatosaurus. Consider that same bone chanced uponby a Roman soldier in the last century bc. Whatever isignied, if anything, to the soldier, it did not signifan Apatosaurus. Agreed?

Agreed. In those circumstances it was more an objecthan a sign, not a fossil at all, so to speak.

And yet itwas a fossil, waiting to be seen through theright eyes. It was not an Apatosaurus signto someone

there and then, in that last century, but it remained thatit was prospectively such a sign for a future observer

Yes,

the colleague conceded,

but that prospective signication was tosomeone,

not tosomething .You raise the diffi cult question of whether the to ofor which of a sign need always be a cognitive orgaism or not. Let me acknowledge the diffi culty of thquestion, but not try to answer it now. Suffi ce it tosay, for the moment at least, that when an organisminterprets something as a sign, that interpretation is

required to complete the signs signication as something actual here and now.

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

33/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 33

11721173117411751176117711781179118011811182118311841185118611871188118911901191

11921193119411951196119711981199

12001201120212031204120512061207

120812091210

R :

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

Voice 3:

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

I can see that. A sign requires an interpretation ifit is to succeed as a sign and not just be some dumbobject. But I dont see how an inorganic substance canprovide an interpretation. Come on!

So,

I continued, proposing to steer the discussion moredirectly to the point at hand,

pay attention: what you call a sign, which I willshortly manifest is a loose rather than a strict way ofspeaking, doesnt just (dyadically) relate to what itsignies, it signies what it signies (triadically)to or for something else. Always hidden in the sign-signi-ed dyad is a third element, thereason why or groundupon which the sign, as you call it, signies whateverit does signify and not something else.

I didnt not see the point, unless my colleague fastened

upon it, which happily did not happen, in pointingout here the important distinction between groundin the technical Peircean sense redolent of the oldobjectum formale of scholastic realism and ground inthe scholastic realist sense of fundamentum relationis.44 Instead, my colleague called for a concrete illustra-tion, much simpler to provide. I secretly breathed asigh of relief.

Give me an example.

Tere was demand in his voice.I hastened to comply, before the absolute point so

pertinent here might occur to my interlocutor (inex-plicably, my friend Joe Pentony, since deceased, cameinto my mind).

I make a noise: elephant. It is not just a noise, buta word. Why, hearing the noise elephant do you not

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

34/66

34 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

12111212121312141215121612171218121912201221122212231224122512261227122812291230

12311232123312341235123612371238

12391240124112421243124412451246

124712481249

Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :S , Voice 3:

think of a thin-legged, long-necked, brown-spottedanimal that nibbles leaves instead of a thick-leggedlarge gray animal with a prehensile proboscis?

Since my colleague fancied to be a realist, it was ndiffi cult to anticipate the reply about to come. Norwas I disappointed.

Obviously because elephant means elephant annot giraffe.

Now my colleage spoke with a touch of impatience

Yes, of course,

I granted,

but is that not only because of the habit structuresinternalized in your Innenwelt which make the noiseelephant a linguistic element in our Lebenswelt o

the basis of which we are habituated to think rst, onhearing the noise, of one particular animal rather thananother? So in the experience of any signication ithere not only the sign loosely so-called and the signed object, but also the matter of the basis upon whicthe sign signies this object rather than or before somother object? You see that?

I do.Ten you see that the relation making what you withyour nger point out as a sign to be a sign is nothinintrinsic to the so-called sign, but rather somethingover and above that subjective structure; to wit, arelationship, which has not one term but two terms,to wit, the signied object for one and, for the other

the reason why that rather than some other is theobject signied?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

35/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 35

12501251125212531254125512561257125812591260126112621263126412651266126712681269

12701271127212731274127512761277

12781279128012811282128312841285

128612871288

R :

S , Voice 1:

V 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R

S , Voice 3:

Voice 1:

I think I do see that. I think. But please explainfurther, so I can be sure.

Realists like to be sure. Infallibility is their ideal goal,as it were, the modern variety at least (rather morenaive in this than their Latin scholastic forebears, Imight add), ironically the nal heirs of Descartes, whoprized certainty, in the end, above realism.

Well, here, history can be a great help. Animals,including human animals, begin with an experienceof objects, and objects normally given as outside of orother than themselves. In order to mature and survive,every animal has to form an interior map, an Innen-welt, which enables it suffi ciently to navigate its sur-roundings to nd food, shelter, etc. Tis suffi ciently iswhat we call an Umwelt, and it contrasts in principlewith, even though it partially includes something of,the things of the physical environment.

I think,

now the demand and impatience gave way to marvel,

I begin to understand your ironic manner wheneverthe subject of realism in philosophy arises. Realistsassume our experience begins with things as such,whereas now I see that our experience directly is only

of things as subsumed within objects and the species-specic structure of an objective world! Ifentia realia and entia rationis are equally objective within ourexperience, then the sorting out of which-is-which isa problem rather than a given!

Exactly so,

I was delighted at this sudden burst of light from mycolleague.

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

36/66

36 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

12891290129112921293129412951296129712981299130013011302130313041305130613071308

13091310131113121313131413151316

13171318131913201321132213231324

132513261327

Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 1:

V 3:

Now if only I can get you to see how object presupposes sign, perhaps we can get some lunch.

Please do so, and, now that you mention it, thequicker the better, for I am getting hungry.

Permit me anobiter dictum, nonetheless, for I thinkit will facilitate our progress to a successful outcomof the main point before us.

By all means,

my colleague allowed, drawing an apple from a baand taking a bite.

Even though you have heretofore deemed yoursela realist,

I ventured,

I have noticed from earlier conversations that youhave a denite partiality to phenomenology, eventhough Husserl himself conceded that his positionin the end proved but one more variant in the char-acteristically modern development of philosophy aidealism.45

So notice two points. First, the phenomeno-logical idea of the intentionality of consciousness46

reduces, within semiotics, to the theory of relations,47

and expresses nothing more than the distinctivecharacteristic of psychological states of subjectivitwhereby they give rise necessarily to relations triadrather than dyadic in character. But second, and morefundamentally, recall the question with which (amonothers) Heidegger concluded his original publicationofBeing and ime:48

Why does Being get conceived proximallyterms of the present-at-handand not in terms ofthe ready-to-hand, which indeed liescloser to us?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

37/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 37

13281329133013311332133313341335133613371338133913401341134213431344134513461347

13481349135013511352135313541355

13561357135813591360136113621363

136413651366

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

Why does this reifying always keep coming backto exercise its dominion?

Within semiotics we can now give an answer to thisquestion.

We can?

Indeed. Ready-to-hand is the manner in whichobjects exist within an animal Umwelt. Humanbeings are animals rst of all, but they have one spe-cies-specically distinct feature of their Innenwelt ormodeling system, a feature which was rst brought tolight in the postmodern context of semiotics, so faras I know, by Professor Sebeok,49 namely, the abilityto model objects as things. Tat is to say, the humanmodeling system or Innenwelt includes the ability toundertake the discrimination within objects of thedifference between what of the objects belongs tothe order of physical subjectivity50 and what belongswholly to the order of objects simply as terminating

our awareness of them.51 Perhaps you recall from yourreading of Tomas Aquinas that he identied theorigin of human experience in an awareness of beingprior to the discrimination of the difference betweenens reale andens rationis?

Actually I dont recall any such discussion in St.Tomas.

Fair enough, and we dont want to get completelyoff the track. Later on you might want to look up thepoint in Aquinas and give some consideration to itsimplications; for it seems to me that what he is sayingis that our original experience includes something ofthe world of things but denitively cannot be reducedto the order ofens reale. Comparative realities and un-

realities alike are discovered from within, not prior to,objectivity.52 Te experience of that contrast, indeed, iswhat transforms the generically animal Umwelt into a

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

38/66

38 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

13671368136913701371137213731374137513761377137813791380138113821383138413851386

13871388138913901391139213931394

13951396139713981399140014011402

140314041405

R :

S , Voice 1:

Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

species-specically human Lebenswelt53 wherein evenwitches can be mistaken for realities of a denite typand wherein it may be hard to realize that the mind-independent revolution of the earth around the sunis not unreal whereas the mind-dependent revolutionof the sun around the earth is not real.

What about Heideggers objective distinction between the ready-to-hand and the present-at-hand?,

my colleague pressed hard.

Simple. Tis is a distinction that does not arise forany animal except an animal with a modeling systemcapable of representing objects (as such necessarilyrelated to us) according to a being or features notnecessarily related to us but obtaining subjectively inthe objects themselves (mistakenly or not, according tthe particular case) an animal, in short, capable owondering about things-in-themselves and conduct-

ing itself accordingly. Now, since a modeling system capacitated is, according to Sebeok, what is meant blanguage in the root sense, whereas the exaptation osuch a modeling in action gives rise not to language bto linguistic communication,54 and since language inthis derivative sense of linguistic communication is thspecies-specically distinctive and dominant modalitof communication among humans, we have a diffi cul

inverse to that of the nonlinguistic animals, althoughwe, unlike they, can overcome the diffi culty.

And what diffi culty is that?

Within an Umwelt, objectsare reality so far as theorganism is concerned. But without language, theanimals have no way to go beyond the objective wor

as such to inquire into the physical environment inits difference from the objective world. Within a Lebenswelt, by contrast, that is to say, within an Umwel

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

39/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 39

14061407140814091410141114121413141414151416141714181419142014211422142314241425

14261427142814291430143114321433

14341435143614371438143914401441

144214431444

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:R :

internally transformed by language, the reality so faras the organism is concerned is confused with andmistaken for the world of things. Objects appearnot as mixtures ofentia rationis withentia realia, butsimply as what is, real being, a world of things.

Tat is the general assertion of realists. It also remindsme of Reids philosophy of common sense.

As well it might.55Descartes and Locke confusedobjects as suprasubjectively terminating relations withtheir counterposed subjective foundations or bases inthe cognitive aspect of subjectivity, thereby reducingUmwelt to Innenwelt; Reid, in seeking to counter themand, especially, Hume after them, confused public ob- jects with things,ens primum cognitum withens reale (inthe earlier terms of Aquinas), thereby reducing Umweltto physical environment. But the physical universe ofthings is distinguished from within the world of objectsas the sense of that dimension of objective experience

which reveals roots in objects that do not reduce to ourexperience of the objects. Reality in this hardcore senseof something existing independently of our beliefs, opin-ions, and feelings is not given to some magical facultyof common sense. Tere is no gift of heaven facilelydiscriminating the real for our otherwise animal minds a gift such as Reid avers56 which only bias or somemistaken religious principle can mislead.

So you are saying that the reality of objects withinexperience, for any animal, is a confused mixture ofentia realia andentia rationis, but that this confusiononly comes to light in the experience of human ani-mals by means of a species-specic modeling of theworld which you call language?

Tat is what I am saying.Well, it makes sense, I think; but it is a strange way

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

40/66

40 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

14451446144714481449145014511452145314541455145614571458145914601461146214631464

14651466146714681469147014711472

14731474147514761477147814791480

148114821483

S , Voice 3:

of speaking. I need to digest this a bit before I candecide where to agree and where to differ. Enoughof yourobiter dictum. I want to get to the bottomof this objects presupposing signs business, and gesome lunch.

Back, then, to history. You can see right off thatevery animal will use what it senses perceptually toorientate itself in the environment. Among these elements sensed some therefore will come to stand fosomething other than themselves. Te most impressiveof such sensory elements would be those manifestinthe powers that hold sway over human existence, nature, on the one hand, and gods, on the other. So inthe ancient consciousness arose the idea ofshmeivon,a natural event which generates in us the expectationof something else, an element of divination in the casof the gods, a symptom in the case of medicine.57 Tisidea permeates the ancient Greek writings. But, at thbeginning of the Latin Age, Augustine unwittingly

introduces a radical variant upon the ancient notion. say unwittingly, not at all to disparage Augustine, bto mark the fact important in this connection that hisignorance of Greek prevented him from realizing whawas novel about his proposal, and how much it stoodin need of some explanation regarding its possibility

Augustine spoke not ofshmeivon but rather ofsignum. And instead of conceiving of it as a natural

sensory occurrence or event he conceived of it simpas a sensible event whether natural or articial. At stroke, by putting the word natural under erasure, Augustine introduced the idea of sign as general mode obeing overcoming or transcending the divsion betweenature and culture . Specically (and incredibly58), forthe rst time and ever after, human language (moreprecisely, the elements and modalities of linguisti

communication) and culture generally came to beregarded as a system of signs (signa ad placita) inter-woven with the signs of nature, thesovhmi; eivbav

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

41/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 41

14841485148614871488148914901491149214931494149514961497149814991500150115021503

15041505150615071508150915101511

15121513151415151516151715181519

152015211522

or, in Augustines parlance,signa naturalia. o a man the Latins followed Augustine in this

way of viewing the sign. But, gradually, problems cameto light. In particular, at least by the time of Aquinas,if not a century earlier in Abaelard,59 question arose asto which is the primary element in the being of sign:being sensible, or being in relation to another? For,the Latins noticed, all of our psychological states, the passiones animae, put us into a relation to what theythemselves are not, and present this other objectivelyin experience.60 Is not this relation of one thing pre-senting another than itself in fact more fundamentalto being a sign than being a sensible element, whethernatural or cultural? And if so, should not the passionsof the soul, which, as effects of things necessarilyprovenate relations to what is objectively experienced,be regarded veritably as signs, even though they arenot themselves directly sensible or, indeed, even out-side of ourselves, outside of our subjectivity?

So at another stroke was overcome the distinc-tion betweeninner and outer as regards the means ofsignication, a landmark event paralleling Augustinesovercoming of the divide between nature and culture.Te states of subjectivity whereby we cathect61 andcognize objects, the scholastics proposed, are them-selves a type of sign, even though we do not accessthem by external sensation. Call them formal signs,they proposed, in contrast to the signs of which

Augustine spoke, which they now proposed to callrather62 instrumental signs.But by now the discussion was no longer exclu-

sively in the hands of the scholastic realists. Te keydistinction this time came rather from the nominalistsafter Ockham; and they were thinking exclusively ofparticular things, alone, according to their doctrine,belonging to the order ofens reale, in contrast to every

relation which is as such anens rationis.63

Out of sometwo centuries of obscurity in which other issues heldthe center stage,64 the Latin discussion of the 16th

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

42/66

42 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

15231524152515261527152815291530153115321533153415351536153715381539154015411542

15431544154515461547154815491550

15511552155315541555155615571558

155915601561

century took a turn in Iberia which was richly tovindicate Peirces later thesis that an essential diffeence separated his Pragmaticism from the varietiespringing up under his earlier label of Pragmatism, ithat to the former scholastic realism is essential, whilthe latter remains compatible with nominalism.

Te decisive realization came cumulatively inthe 16th and 17th centuries through the work ofSoto (1529), Fonseca (1564), the Conimbricenses(1607), Arajo (1617), and nally Poinsot (1632), inwhose writing the decisive realization approximateunmistakable clarity.65 Tis realization was twofold.One part66 lay in the insight that not relation as such,but relation as triadic, constituted the being of thesign, while the sensible element (or, in the case of thformal sign, the psychological element) that occupiethe role of other-representation is what we call a sigin the common, loose way of speaking.67 Te otherpart68 lay in the insight that it is not anything aboutrelation as suprasubjective that determines whether

it belongs to the order ofens reale orens rationis, butwholly and solely the circumstances of the relation.69 Whence one and the same relation, under one set ofcircumstancesens reale, by change of those circum-stances alone could pass into anens rationis withoutany detectable objective difference in the direct experence of the animal.

Ten came the virtual extinction of semiotic con-

sciousness that we call modernity, a dark age that dinot really end until Peirce returned to the late Latinwritings and resumed the thread of their developingsemiotic consciousness, rst by explicitly naming ththree elements or terms grounding the triadic signrelation, and then by shifting the emphasis from be-ing to action with the identication of semiosis. Teforeground element of representation in the sign rela

tion Peirce termed therepresentamen.70

Tis is whatis loosely called a sign, but in reality is a sign-vehicconveying what is signied to some individual or com

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

43/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 43

15621563156415651566156715681569157015711572157315741575157615771578157915801581

15821583158415851586158715881589

15901591159215931594159515961597

159815991600

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

munity, actual or prospective. Te other representedor conveyed by the sign-vehicle Peirce traditionallytermed thesignicate orobject signied (in this two-word expression, to tell the truth, the rst word isredundant). Whereas the prospective other to whichrepresentation is made (emphatically not necessarilya person, as Peirce was the rst to emphasize71 andlater semiotic analysis was to prove72) Peirce termed73 theinterpretant, the proper signicate outcome of theaction of signs.

My colleague interrupted my historical excursus atthis point.

Do you really mean to call the period between Des-cartes and Peirce the semiotic dark ages? Isnt that alittle strong?

Well,

I half apologized.

Te shoe ts. Nor do the semiotic dark ages simplyend with Peirce, I am afraid. Tey extend into thedawn of our own century, though I am condentwe are seeing their nal hours. After all, a darknessprecedes every full dawn.

I saw an ad for a new book of yours comparingtodays philosophical establishment with the judgesof Galileo. Tats not likely to get you job offers at thetop, my colleague admonished.

Yes,

I sighed;

the ad drew on theAviso prefacing my history ofphilosophy.74 It was calculated, well or ill, to sell the

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

44/66

44 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

16011602160316041605160616071608160916101611161216131614161516161617161816191620

16211622162316241625162616271628

16291630163116321633163416351636

163716381639

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

book to those disaffected from the philosophical sidof modernity, its dark side,75 as distinguished fromthe glorious development of ideoscopic76 knowledgethat we call science.

Idioscopic?

I was sure my interlocutor spelled the term in question with an i rather than an e after the d, givexpertise in Greek. But since our exchange was novisual on the point, I escaped a demand to account fomy deviation from correct Greek-derived orthographyInstead, I was able simply to explain:

Knowledge that cannot be arrived at or verifiedwithout experimentation and, often, the help ofmathematica formulae.

As opposed to what? Common sense?

No, as opposed to cnoscopic77 knowledge, thesystematic realization of consequences implied by theway we take reality to be in those aspects wheredirect experimentation, and still less mathematiza-tion, is of much avail. In semiotics,78 this distinc-tion has been explained as the distinction betweendoctrina andscientia as the scholastics understoodthe point prior to the rise of science in the modern

sense. Peirce himself 79

characterized the distinctionas cenoscopic vs. idioscopic, borrowing these terfrom Jeremy Bentham.

More strange terminology. Why cant semioticiantalk like normal people? And by the way, is Peirceusage faithful to that of Bentham, and is Benthamactually the originator, the coiner, of these terms?

Normal is as normal does,

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

45/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 45

16401641164216431644164516461647164816491650165116521653165416551656165716581659

16601661166216631664166516661667

16681669167016711672167316741675

167616771678

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

S , Voice 1:

R :

S , Voice 3:

I said with mild exasperation.

How can you develop new ideas without newwords to convey them? Of course old words used inunfamiliar ways can also serve, but tend to misleadin any case. Surely you wont deny that new insightsrequire new ways of speaking? Perhaps youve beenan undergraduate teacher too long.

Point taken,

my colleague allowed ruefully.

But what about the reliability of Peirces usage vis--vis Benthams coinage of these terms, if he did cointhem?

As to the exact relation of Peirces appropriation tothe sense of Benthams original coinage, I cant helpyou there. I have never looked into Bentham directly.

But I nd the distinction in Peirce useful, even cru-cial, to understanding the postmodern developmentof semiotics.

My colleague, returning abruptly at this point tomy interrupted historical excursus, said:

You said just now that what I would call the common

sense notion of sign, a particular thing representingsomething other than itself, Peirce called technicallya representamen, and that this is not the sign itselftechnically speaking but what you rather termed asign-vehicle, functioning as such only because it isthe foreground element in the three elements whoselinkage or bonding makes up the sign technically orstrictly speaking.

Yes,

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

46/66

46 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

16791680168116821683168416851686168716881689169016911692169316941695169616971698

16991700170117021703170417051706

17071708170917101711171217131714

171517161717

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

Voice 3:

R :

I allowed,

you have followed me well. What makes somethinappear within sense-perception as a sign in the common or loose sense is not anything intrinsic to thephysical subjectivity of the sensed object as a thinbut rather the fact that the objectied thing in ques-tion stands in the position of representamen within atriadic relation constituting a sign in its proper beingtechnically and strictly. So that physical structurebefore the building in your line of vision that tellyou this is no longer Monaghan House is a sign nostrictly but loosely. Strictly it is the element of otherrepresentation within a triadic relation having youwith your semiotic web of experience and privatsemiosis as a partial interpretant, and this buildinghere housing my offi ce among other things as its signed object. Moreover, note that the physical structureof the particular thing appearing in your Umwelt asa sign may be subjected to ideoscopic analysis, bu

that that analysis will never reveal its sign-status asuch. Te recognition of signs as triadic relations incontrast to related things as subjective structures is astrictly cnoscopic achievement, although of coursthe semiosis of such things can well be developeideoscopically by the social sciences, and philosophwill then be obliged to take such ideoscopic developments into account if it wishes to keep up with the

reality of human experience as a whole.Now that is amazing.

My colleague seemed delighted.

What is amazing?

Tat I now see what you mean in saying that a signis what every object presupposes. You mean that everobject as an object depends upon a network of triadi

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

47/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 47

17181719172017211722172317241725172617271728172917301731173217331734173517361737

17381739174017411742174317441745

17461747174817491750175117521753

175417551756

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 3:

S , Voice 1:S , Voice 3:

relations, and that precisely these relations constitutethe being of a sign strictly speaking. Hence withoutobjects there would be isolated sensory stimuli, butno cathexis,80 no cognition, establishing a world ofobjects wherein some appear desirable (+), othersundesirable (), with still others as matters of indif-ference ().

Tat is only part of it.

Part of it?

Yes. Every sign acting as such gives rise to furthersigns. Semiosis is an open process, open to the worldof things on the side of physical interactions and opento the future on the side of objects. Tus you need toconsider further that sign-vehicles or representamens,objects signied or signicates, and interpretants canchange places within semiosis. What is one time anobject becomes another time primarily sign-vehicle,

what is one time interpretant becomes another timeobject signied, and what is one time object signiedbecomes another time interpretant, and so on, in anunending spiral of semiosis, the very process throughwhich, as Peirce again put it, symbols grow.

So signs have a kind of life within experience, in-deed provide experience almost with its soul in the

Aristotelian sense of an internal principle of growthand development! One mans object is another manssign, and an object one time can be an interpretantthe next.

Now youre getting the idea. Be careful. Next thingyou know youll claim to be a semiotician.

So signs strictly speaking are invisible.Yes, and inaudible and intactile, for that matter. By

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

48/66

48 TAJS 20.1 4 (2004)

17571758175917601761176217631764176517661767176817691770177117721773177417751776

17771778177917801781178217831784

17851786178717881789179017911792

179317941795

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

R :

S , Voice 1:

S , Voice 3:

contrast, a signloosely speaking , the an element occu-pying the position of representamen in a renvoi rela-tion vis--vis signicate and interpretant, can indeebe seen and pointed to or heard. A great thinker ofthe 20th century once remarked,81 perhaps withoutrealizing the full depth of what he was saying, thaanimals other than humans make use of signs, butthose animals do not know that there are signs. Tevehicles of signs can normally be perceived (as lonas they are instrumental rather than formal) andcan become rather interpretants or signieds; butthe signs themselves are relations, like all relations ireducibly suprasubjective, but unique too in being irreducibly triadic. Signs, in short, strictly speaking cabeunderstood but not perceived; while signs looselyspeaking can beboth perceivedand understood, butwhen they are fully understood it is seen that whatwe call signs loosely are strictly representamens,the foreground element in a given triadic relationthrough which alone some object is represented to

some mind, actually or only prospectively.

What do you mean prospectively?

I sighed.

You bring up another story for which the world isnot yet prepared.

I do?

My colleague looked worried, perhaps seeing luncdisappearing in a cloud of verbiage, and having haenough of the case of the giant rat of Sumatra on thetable between us, still staring beady-eyed his way.

Indeed you do. Remember a little while ago whethe subject of evolution came up?

-

8/14/2019 A SIGN IS WHAT?

49/66

A Sign IsWhat ? Deely 49