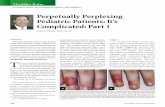

A Perplexing Sinus Lift Complication

description

Transcript of A Perplexing Sinus Lift Complication

-

Case Report

Management of a Perplexing Sinus Lift Complication

Gary Greenstein* and John Cavallaro Jr.*

Background: This case report describes a dilemmathat occurred after a maxillary right lateral window si-nus lift was performed. The patient developed a gnaw-ing pain in the sinus region but manifested no signs ofsinusitis, and the subjacent teeth were asymptom-atic. Differentiating between a pain that could be orig-inating in the maxillary sinus or adjacent premolarswas problematic.

Methods: After several weeks, a CT scan revealedno signs of sinusitis, despite the patients belief thather discomfort was caused by her sinus lift. By theprocess of elimination, the decision was made to ex-tract subjacent, asymptomatic premolars that had50% bone loss and were previously endodonticallytreated.

Results: Extraction of asymptomatic premolarsresulted in total elimination of her pain.

Conclusions: A differential diagnosis with regard tothe source of the patients pain had to be arrived at bythe process of elimination rather than by validation.Confirmation that there was no sinus infection facili-tated making the decision to remove asymptomaticpremolars. J Periodontol 2010;81:776-782.

KEY WORDS

Bone regeneration; case report; complications;dental implants; maxillary sinus; sinusitis; woundhealing.

Alateral wall sinus lift is a method to augment

the posterior ridge when the crestal alveolarbone subjacent to the maxillary sinus is

deficient and cannot support a dental implant.1 Afterflap elevation, a lateral window is created in thebuccal plate of bone, the schneiderian membrane iselevated, and a bone graft is placed in the spacecreated by membrane elevation. This is a routineprocedure; however, complications can occur. Theincidence of sinus infections is around 3%, despiteadministration of antibiotics.2 Recently, a sinus liftdone by one of the authors (GG) resulted in a patienthaving discomfort for 3 months until several perplex-ing issues were resolved. This case report describessteps taken to diagnose and eliminate the patientspain.

PATIENT MEDICAL AND DENTAL HISTORY

The patient was a 57-year-old, medically healthy,white woman with a long history of being a periodontalpatient. She was treated initially in 1987 for chronicsevere generalized periodontitis (surgical and non-surgical therapy). Subsequently, the patient re-mained in maintenance every 3 months, and otherperiodontal procedures were performed as needed.In June of 2009, she desired to prosthetically restoresections of her mouth. Because of lack of alveolarbone in the maxillary right region, a sinus lift was per-formed in preparation for placement of an implant atsite #3. In the maxillary right quadrant, teeth #1 and#2 were missing and teeth #4 and #5 had 50% boneloss (Fig. 1). The maxillary premolars (#4 and #5)were previously endodontically treated (12 and 15years ago, respectively), restored with crowns, andtooth #5 had an apicoectomy 10 years ago. The teethwere functional and asymptomatic. Both premolarshad shallow probing depths (2 to 3 mm; there was 5mm of recession) and class I mobility (1 mm hyper-mobility). Before the sinus lift, treatment options werediscussed with the patient, which included removingteeth #4 and #5 and expanding the sinus lift to planfor a prosthesis that would include replacement ofteeth #3 through #5. She desired to retain teeth #4

* Formerly, Department of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, New YorkUniversity College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

Private Practice, Surgical Implantology and Periodontics, Freehold, NJ. Private Practice, Surgical Implantology and Prosthodontics, Brooklyn, NY. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090639

Volume 81 Number 5

776

-

and #5. Previously, tooth #6 was replaced with a den-tal implant.

CHRONOLOGY OF TREATMENT

June 3, 2009A lateral window sinus lift was performed in the max-illary right posterior region. The procedure was un-eventful and proceeded without difficulty. Themembrane was elevated without creating a perfora-tion and the postoperative panoramic radiographindicated that the sinus graft material was well con-tained (Fig. 2). The inserted graft material was de-mineralized bovine bone (hydrated with sterilesaline) and a collagen barrieri was placed over thelateral window. The patient was prescribed amoxicil-lin, 2 g 1 hour before the procedure, and continuedtaking amoxicillin, 500 mg tid, for 7 days.

June 10, 2009The patient reported no problems at a routine postop-erative appointment.

June 17, 2009She complained of hypermobility and sensitivity ontooth #4. The tooth was equilibrated, and her discom-fort was eliminated.

July 3, 2009She had discomfort. Teeth #4 and #5 were equili-brated.

July 5, 2009She described gnawing pain in the sinus area duringthe evening. A panoramic radiograph was taken(Fig. 3). The sinus was clear. There were no clinicalsymptoms of sinusitis. Metronidazole, 500 mg tidfor 7 days, was prescribed as a precautionary mea-sure.

July 10, 2009She indicated that the gnaw-ing pain at night comes andgoes. The antibiotic wascontinued for another week.

July 13, 2009She still had discomfort.There were no signs of sinus-itis. Teeth #4 and #5 wereasymptomatic to percussionandpalpation,probingdepthswere shallow, and there wasno increased hypermobilityon teeth #4 and #5. The teethwere transilluminated to checkfor a vertical root fracture,and the patient was askedto bite on a tongue blade indifferent positions to check

for a fracture. The patient was referred for an end-odontic consultation. The endodontist indicated thatthere was no pathosis on teeth #4 and #5 and no ap-parent endodontic reason for the patients pain.

July 19, 2009Her discomfort persisted; it was relieved with analgesicat night. There were still no clinical signs of pathosis.She was referred for an oral surgery consult. It was sug-gested to remove the sinus graft because when the lat-eral wall of the graft was pressed, she felt minorsoreness. The patient did not want to do that, and theauthors believed that without clinical signs of sinusitisor an intraoral infection, there was no justification to re-move the graft.Clindamycinwas prescribed but the pa-tient developed hives in 1 day, so the drug wasdiscontinued.

July 26, 2009Her discomfort continued, and she manifested no clin-ical signs of pathosis. The patient was prescribedmethylprednisolone# and amoxicillin to resolve all is-sues. In actuality, this was shotgun therapy becausethe etiology of the problem was undiagnosed.

August 3, 2009The patients pain subsided for 5 days and then re-sumed. She was referred for a CT scan, which shedid not immediately obtain. Consideration was givento referring thepatient toanotolaryngologist.However,the patient did not have a problem before the sinus lift,there were no symptoms of a sinus infection, the graftwas well contained, and it was believed that the etiol-ogy of the patients problem was of dental origin.

Figure 1.CT (panoramic view) of the maxillary right quadrant depicting a clear maxillary right sinus before the sinus lift wasperformed. R = right; L = left.

Bio-Oss, Osteohealth, Shirley, NY.i BioMend, Zimmer Dental, Carlsbad, CA. Tylenol 3, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Titusville, NJ.# Medrol dose pack, Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals, New York, NY.

J Periodontol May 2010 Greenstein, Cavallaro

777

-

August 9, 2009Her gnawing pain in the evening continued.

August 15 and 16, 2009On August 15, the patient went for a CT scan. She wasseen in the office the next day, August 16. The scandemonstrated that the sinus graft was contained,and the sinus was clear (Fig. 4). At this juncture,the patient wanted the sinus graft removed becauseshe wanted her pain-free life back again. It was sug-gested to retain the graft, because it looked fine andthere were no signs of sinusitis. Furthermore, it wasrecommended that teeth #4 and #5 be removed, de-spite the fact that they were asymptomatic on clinicaland radiographic inspection. In consultation with thepatient, it was decided to remove these teeth, one ata time.

August 21, 2009Tooth #5, the tooth that had the apicoectomy, was re-moved first. The next day she reported her discomfortwas not eliminated.

August 23, 2009Tooth #4 was extracted.

August 25, 2009She was in extreme pain. She had a local osteitis at site#4. The socket was irrigated with saline and treatedwith eugenol and gauze. Her pain was eliminated.

August 26 and 28, 2009On both days, she had pain from the alveolus. Thesocket was irrigated and retreated with eugenol on

gauze. Each time her painwas temporarily relieved for1 or 2 days.

September 2 and 7, 2009The socket was retreatedwith irrigation and eugenolon gauze.

September 12, 2009The patient was comfortable.She had no more discomfort.

DISCUSSION

The patient was completelycomfortable 3 months afterthe sinus lift. There were sev-eral aspects of this case thatmade it difficult to expedi-tiously eliminate the patientsdiscomfort. Namely, it wasnot easy to identify the sourceof her pain; it was most likelyeither from an infected maxil-

lary right sinus or her maxillary right premolars werereferring pain to the sinus region. Removal of the sinusgraft or the teeth without validating the source of thediscomfort was undesirable because both procedureshad negative consequences and might not eliminateher pain.

Initially, it was believed that her distress was causedby traumatic occlusion on the maxillary right bicus-pids, which were slightly hypermobile after the sinuslift. She manifested no signs of distress after the pre-molars were occlusally equilibrated. Two weeks later,she related that the teeth felt high, and she hada gnawing pain. Following her second occlusal adjust-ment, the teeth were asymptomatic, but the gnawingpain persisted. She described it as if someone wasputting a screw into her bone, which was interpretedto suggest the possibility of a sinusitis. A panoramicfilm was obtained, which demonstrated that the sinusgraft was contained and the sinus was clear (Fig. 2).

To rule out the possibility of a sinus infection, thepatient was visually inspected and palpated intraor-ally and extraorally at each appointment. When shebent over there was no pain, indicating an absenceof excess fluids in the sinus. Her continuing discom-fort, despite no appearance of a sinus infection (swell-ing, pain on palpation), was puzzling. There was nopurulent discharge from the nostrils. A differential di-agnosis was confounded by the fact that the two pre-molars (teeth #4 and #5) manifested no signs orsymptoms of pathosis clinically or radiographically(Figs. 5 and 6) after her occlusal equilibration. Theteeth were asymptomatic on percussion, luxation,

Figure 2.Panoramic radiograph on the day that the sinus lift was placed. It demonstrates a well-contained sinus graft.

A Perplexing Sinus Lift Complication Volume 81 Number 5

778

-

and buccal plate palpation. The probing depthsaround these teeth were shallow and radiographicallythere was no appearance of radiolucency. Transillu-

mination3 and occlusal testing4 for a fracture werenegative. There was no swelling or a fistulous tract in-dicating apical pathosis.

A condition referred to asmaxillary sinusitis of dentalorigin was considered inthe differential diagnosis,5

and occurs when a dental in-fection causes destruction ofthe cortical bone and extendsinto the sinus. However, be-sides intermittent discom-fort, the patient did notmanifest signs of a sinus in-fection, the teeth wereasymptomatic, and the ra-diographs revealed intactcortical bone apical to thepremolars on a periapical ra-diograph (Fig. 5) and on theCT scan (Fig. 6). The bicus-pids were endodonticallytreated many years ago,and clinical and radiographicassessments provided noinformation to suggest thatthe teeth were inducing si-nusitis. Another symptom

Figure 3.Panoramic radiograph taken 4 weeks after the sinus graft was placed, indicating that the sinus area wasclear and that the graft was well contained.

Figure 4.CT scan confirms that the sinus was clear, and the graft was well contained. R = right. Horizontal Lines (Red and Blue) indicate cross sections availablefor viewing. Horizontal Lines (Blue) indicate height of anatomy available for viewing in cross-sections.Tick Dist = Distance in mm from the most coronalaspect of the scan, which is 0; 100.00 = 100mm from top of scan; 120 = 120mm from top of scan.

J Periodontol May 2010 Greenstein, Cavallaro

779

-

considered was the patients statement that the painwas worse at night. It was recognized that posture canaffect blood pressure; when a patient lies down, thereis less gravitational pull and a reduced influence ofthe baroreceptor system, which can result in in-creased perfusion pressure at an inflamed site.6 Thus,the increased pain at night and a throbbing sensationhad a physiologic basis, but did not help differentiatebetween sinus or tooth-derived pain.

The patients discomfort was relieved at night withibuprofen, 600 mg, or acetaminophen. The possibilitythat there were trigger points associated with a neural-gia that would induce her distress was assessed andresulted in no atypical findings.7 The only sign of dis-comfort noted was when the lateral wall of the sinusgraft was pushed, she stated it felt sore. The sorenesswas minor and could be attributed to dissolution ofa resorbable barrier over a site where the lateral win-dow osteotomy was performed.

In the maxilla, pain is frequently referred from themaxillary sinus to teeth because of the close anatomicassociation between the floor of the sinus and roots ofmaxillary teeth.8,9 In particular, when a patient has al-

lergies, the lining of their sinus tissues can become in-flamed, and the patient perceives the discomfort asdental in origin, but it may be caused by sinus inflam-mation. Conversely, a tooth can refer pain to thesinus.9 However, usually the offending tooth is symp-tomatic or at least manifests a radiolucency that is in-dicative that the endodontic result is less than ideal.10

In this regard, it was considered that the teeth sub-jacent to the sinus might be causing the pain. It wasperplexing that the teeth never demonstrated anysigns or symptoms of pathosis after her occlusalequilibration. In general, an asymptomatic endo-dontically treated tooth that appears normal on aperiapical radiograph usually indicates endodontictreatment was successful. However, there are reportsthat even if a periapical area seems resolved on a ra-diograph, microorganisms may persist indefinitely11

and an inflammatory process could be associatedwith endodontically treated teeth that appear radio-graphically normal.5,12-15 Pertinently, others reported30% of the buccal or lingual plate needs to be resorbedbefore an apical lesion appears on a radiograph.16

Therefore, it is possible that the pain referred to the si-nus area was caused by an undetectable lesion at theapex of the premolars; and there was stimulation ofperipheral and central nociceptors by dolorific sub-stances, such as bradykinin, prostaglandins, leukotri-enes, histamines, and so forth.17 Initiation of her painmay have been precipitated by the sinus membraneelevation over the second premolar, which compro-mised the tooths vascular supply, or possibly an api-cal lesion was irritated by instrumentation. These arehypothetical explanations, and there is no way to pre-cisely identify the precipitating factor that resulted inthe patient developing pain 2 weeks after completionof the sinus lift.

Nevertheless, the literature was searched to ascer-tain if additional factors should be considered whenconfronted with a situation similar to the one pre-sented in this case report. Several perspectives wereinvestigated: prevalence of maxillary roots in the si-nus, vascularity of endodontically treated teeth, andregional alterations of vascularity associated with si-nus lifts.

Roots of maxillary molars or premolars can protrudeinto the sinus cavity, but this occurs less often than ex-pected because conventional radiographs are mislead-ing. It was reported that the sinus floor extendsbetween adjacent teeth or between individual rootsin about half of the population.18 However, it has beenhistologically demonstrated that most roots that ap-pear radiographically to protrude into the sinus aresurrounded by a thin layer of cortical bone and thisbone is perforated 14% to 28% of the time.19 Further-more, when panoramic films and CT scans werecompared, only 39% of subjects manifesting roots

Figure 5.Periapical films of teeth #4 and #5 demonstrate that there was anintact cortical plate of bone around the apices of the premolars.

Figure 6.CT scan of teeth #4 (sections 24 and 22) and #5 (sections 20 and18) confirms that the apices of the premolars did not penetrate intothe sinus and did not manifest any apparent radiolucencies.

A Perplexing Sinus Lift Complication Volume 81 Number 5

780

-

projecting into sinus in panoramic radiographsshowed protrusion on CT images.20 These findingsconfirm that apices of teeth may be exposed whenthe sinus membrane is elevated.

The blood supply to teeth is derived from threesources: 1) periodontal ligament, 2) periosteum,and 3) endosteal vessels.21 If endodontics are per-formed, the tooth remains embedded in a highly vas-cular periodontal ligament22 and blood supply at theapex is similar to a vital tooth.23 Likewise, healing isassociated with the formation of new blood vesselsif a tooth had a successful apicoectomy.24 No datawere located that indicated endodontically treatedteeth have compromised apical vascularity, therebymaking them more susceptible to failure than vitalteeth.

There are vascular changes in the bone precedinga sinus lift. Investigators noted that the maxilla isdensely vascularized in dentate subjects;25,26 how-ever, the blood supply is permanently reduced (diam-eter and number of vessels decrease) with aging andatrophy of bone after tooth removal.27 Eventually, theantral floor can be diminished to a thin layer of com-pact bone.28,29 Because thin bone cannot be suppliedwith centromedullary vessels, it may only be suppliedperiosteally.30 Furthermore, it is possible at locationsalong the sinus floor that there is no bone or bloodvessels.31 Therefore, it seems that reduction of subantralbone is associated with alterations of blood supply tothe floor of the sinus.

With respect to blood supply to the sinus region,there are three primary blood vessels: 1) the posteriorlateral nasal artery, 2) the posterior superior alveolarartery, and 3) the infraorbital artery.30,32 The lattertwo form intraosseous and extraosseous anastomo-ses in the lateral antral wall and provide vascularityto the schneiderian membrane.30 These blood vesselsmay be transected during creation of the lateral win-dow, thereby decreasing blood supply to the region.33

Furthermore, Traxler et al.33 indicated that the peri-osteum should be separated with great care to pre-vent damage to extraosseous anastomoses. In thisregard, it has been suggested that when elevatingthe schneiderian membrane, if teeth protrude intothe sinus it is possible to devitalize them.34 Theoreti-cally, this could occur by severing the nerve or vas-cular supply at the apex. However, no studies werefound that addressed this issue.

The last enigma related to this case is referred pain,which can be a perplexing problem. It may lead to in-appropriate dental care if the origin of pain is notfound.35 Pertinently, the lack of signs indicating a si-nus infection dictated not to remove the sinus graft.Similarly, failure to detect signs suggesting that thepremolars were the source of her pain precluded,reaching the conclusion that teeth #4 and #5 should

be removed. The dilemma was that the patient had in-termittent pain that she believed was originating in hersinus, and it had not resolved despite several coursesof antibiotics. A CT scan was ordered 5 weeks aftershe became symptomatic. In retrospect, the CT scancould have been obtained sooner to rule out the pos-sibility of a sinus infection because this determinationcould not be made based solely on clinical findings.Discussion was initiated regarding removal of asymp-tomatic teeth (#4 and #5) once the CT scan demon-strated a well-contained sinus graft and a clearsinus. There was a concern that the teeth could be re-moved, and if the pain persisted another predicamentwould have been created. The decision was made toproceed with extraction of asymptomatic teeth andto maintain the sinus graft. When the teeth were ex-tracted the apices of the teeth were examined, andthe gutta percha did not protrude past the root apices.As indicated, her relief was postponed because of de-velopment of a local osteitis at site #4. There was noapparent reason for development of a local osteitis,and when it resolved the patient was comfortable.

CONCLUSIONS

In retrospect, numerous times the decision to removethe sinus graft seemed more logical than removal ofasymptomatic premolars. However, failure to validatethe presence of a sinus infection and reluctance to re-move the sinus graft was a motivation not to give intoexpediency. It is unknown why the premolars becameexacerbated subsequent to the sinus lift procedure.Hypothetically, membrane elevation over tooth #4or the initial occlusal trauma may have precipitateda sequence of biochemical or bacterial events that re-sulted in referred pain, while the premolars remainedasymptomatic. Ultimately, the patient was verypleased that the sinus graft was not removed becauseits presence will facilitate her receiving dental im-plants at sites #3 and #4 and a fixed prosthesis to in-clude her first molar.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors report no conflicts of interest related tothis case report.

REFERENCES1. Raja SV. Management of the posterior maxilla with

sinus lift: Review of techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg2009;67:1730-1734.

2. Schwartz-Arad D, Herzberg R, Dolev E. The prevalenceof surgical complications of the sinus graft procedureand their impact on implant survival. J Periodontol2004;75:511-516.

3. Ailor JE Jr. Managing incomplete tooth fractures. JAm Dent Assoc 2000;131:1168-1174.

J Periodontol May 2010 Greenstein, Cavallaro

781

-

4. Christensen GJ. The cracked tooth syndrome: Apragmatic treatment approach. J Am Dent Assoc 1993;124:107-108.

5. Tataryn RW. Rhinosinusitis and endodontic disease.In: Ingle JI, Balkind LK, Baumgartner JC, eds. InglesEndodontics, 6th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker;2008:626-637.

6. Pashley DH, Walton RE, Slavkin HC. Histology andphysiology of the dental pulp. In: Ingle JI, Balkind LK,Baumgartner JC, eds. Ingles Endodontics, 6th ed.Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2008:25-62.

7. Sawaya RA. Trigeminal neuralgia associated withsinusitis. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2000;62:160-163.

8. Okeson JP, Falace DA. Nonodontogenic toothache.Dent Clin North Am 1997;41:367-383.

9. Rotstein I, Simon HS. Endodontic-periodontal interre-lationships. In: Ingle JI, Balkind LK, Baumgartner JC,eds. Ingles Endodontics, 6th ed. Hamilton, Ontario:BC Decker; 2008;638-659.

10. Ehrmann EH. The diagnosis of referred orofacialdental pain. Aust Endod J 2002;28:75-81.

11. Brynolf I. A histological and roentgenological study ofthe peri-apical region of upper incisors. Odontol Revy1967;18(Suppl. 11):1-176.

12. Green TL, Walton RE, Taylor JK, Merrell P. Radio-graphic and histologic periapical findings of root canaltreated teeth in cadaver. Oral Surg Oral Med OralPathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997;83:707-711.

13. Seltzer S. Long-term radiographic and histologicalobservations of endodontically treated teeth. J Endod1999;25:818-822.

14. Rowe AH, Binnie WH. Correlation between radiologicaland histological inflammatory changes following rootcanal treatment. J Br Endod Soc 1974;2:57-63.

15. Lin LM, Skribner JE, Gaengler P. Factors associatedwith endodontic treatment failures. J Endod 1992;18:625-627.

16. Ortman LF, McHenry K, Hausmann E. Relationshipbetween alveolar bone measured by 125I absorptiom-etry with analysis of standardized radiographs: 2.Bjorn technique. J Periodontol 1982;53:311-314.

17. Jacinto RC, Gomes BP, Shah HN, Ferraz CC, Zaia AA,Souza-Filho FJ. Quantification of endotoxins in ne-crotic root canals from symptomatic and asymptom-atic teeth. J Med Microbiol 2005;54:777-783.

18. Hauman CH, Chandler NP, Tong DC. Endodonticimplications of the maxillary sinus: A review. IntEndod J 2002;35:127-141.

19. Wehrbein H, Diedrich P. The initial morphologicalstate in the basally pneumatized maxillary sinus: Aradiological-histological study in man (in German).Fortschr Kieferorthop 1992;53:254-262.

20. Sharan A, Madjar D. Correlation between maxillarysinus floor topography and related root position ofposterior teeth using panoramic and cross-sectionalcomputed tomography imaging. Oral Surg Oral MedOral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006;102:375-381.

21. Nobuto T, Imai H, Suwa F, et al. Microvascularresponse in the periodontal ligament following muco-periosteal flap surgery. J Periodontol 2003;74:521-528.

22. Gutman JL. History of endodontics. In: Ingle JI,Balkind LK, Baumgartner JC, eds. Ingles Endodon-tics, 6th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2008:43.

23. Huettner RJ, Young RW. The movability of vital anddevitalized teeth in the Macacus rhesus monkey. OralSurg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1955;8:189-197.

24. Lin LM, Di Fiore PM, Lin J, Rosenberg PA. Histologicalstudy of periradicular tissue responses to uninfectedand infected devitalized pulps in dogs. J Endod2006;32:34-38.

25. Marx RE. Clinical application of bone biology tomandibular and maxillary reconstruction. Clin PlastSurg 1994;21:377-392.

26. Bell WH, You ZH, Finn RA, Fields RT. Wound healingafter multisegmental Le Fort I osteotomy and tran-section of the descending palatine vessels. J OralMaxillofac Surg 1995;53:1425-1433; discussion 1433-1434.

27. Soikkonen K, Wolf J, Hietanen J, Mattila K. Threemain arteries of the face and their tortuosity. Br J OralMaxillofac Surg 1991;29:395-398.

28. Watzek G, Solar P, Ulm C, Matejka M. Surgical criteriafor endosseous implant placement: An overview. PractPeriodontics Aesthet Dent 1993;5:87-94; quiz 96.

29. Ulm CW, Solar P, Gsellmann B, Matejka M, Watzek G.The edentulous maxillary alveolar process in the regionof the maxillary sinus: A study of physical dimension.Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995;24:279-282.

30. Solar P, Geyerhofer U, Traxler H, Windisch A, Ulm C,Watzek G. Blood supply to the maxillary sinus relevantto sinus floor elevation procedures. Clin Oral ImplantsRes 1999;10:34-44.

31. Selden HS. The interrelationship between the maxil-lary sinus and endodontics. Oral Surg Oral Med OralPathol 1974;38:623-629.

32. Norton NS, ed. Netters Head and Neck Anatomy forDentistry. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007:299301.

33. Traxler H, Windisch A, Geyerhofer U, et al. Arterialblood supply of the maxillary sinus. Clin Anat 1999;12:417-421.

34. van den Bergh JP, ten Bruggenkate CM, Disch FJ,Tuinzing DB. Anatomical aspects of sinus floor eleva-tions. Clin Oral Implants Res 2000;11:256-265.

35. Falace DA, Reid K, Rayens MK. The influence of deep(odontogenic) pain intensity, quality, and duration onthe incidence and characteristics of referred orofacialpain. J Orofac Pain 1996;10:232-239.

Correspondence: Gary Greenstein, 900 West Main St.,Freehold, NJ 07728. Fax: 732/780-7798; e-mail: [email protected].

Submitted November 16, 2009; accepted for publicationJanuary 9, 2010.

A Perplexing Sinus Lift Complication Volume 81 Number 5

782