A NEW VIEW OF COPYRIGHT

-

Upload

peyton-david -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of A NEW VIEW OF COPYRIGHT

92 1 New View of Copyright

Almarin Phillips, “The Impossibility of Competition in Telecommunications: Public Policy Gone

Richard A. Posner, “Taxation by Regulation,” Bell Journal o f Economics and Management Science, Awry,” in Regulatory Reform and Public Utilities, Michael Crew (editor), 1982.

Vol. 2 (Spring 1971), pp. 22-50.

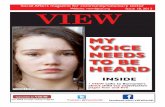

A NEW VIEW OF COPYRIGHT

David Peyton

Legal analysis has long dominated public policy debates on copyright. However, recent developments call into question the adequacy of the legal perspective. A new view of copyright is needed, given the rapid change in the information industries.

Fully 5 percent of the U.S. Gross National Product is now subject to copyright protec- tion.’ Despite the omnibus copyright revision of 1976, legal and business relations remain in flux. Although meant to make future copyright legislation largely unnecessary, the revised federal Copyright Act has served rather as a precursor to a continuing flow of proposed amendments on cable television, satellite reception, videocassette recorders, semiconductor chips, and other subjects. An especially significant amendment adopted in 1980 implemented the recommendation of a Presidential study commission that com- puter software be brought clearly under the Act. After much debate about another pro- posed amendment, the 1984 Semiconductor Chip Protection Act instead created a new, copyright-like protection for chips. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court reminded millions of Americans that they use copyrighted products in their homes all the time-TV pro- grams-when it ruled in the Sony “Betamax” case that limited videotaping was not copyright infringement. Finally, in April 1986, the Office of Technology Assessment deliv- ered a major report to Congress on intellectual property-copyrights and neighboring concepts of intangible ownership. Major issues include how new kinds of works will fit accepted legal definitions of what can be protected; what rights could be attached to them; and how such rights could be accepted and enforced.

INTEREST-BALANCING VERSUS POLICY ANALYSIS

Michael O’Hare’s recent economic analysis of copyright inJPAM* was not only timely but also a welcome new addition to conventional legal analysis. It was perhaps even an antidote to the pervasive legal viewpoint, which seems unable to escape its traditional “interest-balancing” metaphor. More such policy analysis is needed. The interest-balanc- ing approach correctly recognizes that encouraging authorship now and in the future calls for a measure of protection for producers, with attendant costs to current and future users. However, legal interest-balancing leads to no unique solutions, only acceptable bargaining outcomes. The law can more easily recognize the existence of competing interests than measure relative costs and benefits. Even more to the point, interest-bal- ancing embodies no clear notion of net social gain.

The bargaining approach to policy can lead to unfortunate results. The copyright dis- pute between cable television operators and the originators of their programming pro- vides a good example. From the 1950s onward, entrepreneurs in areas with bad TV reception began receiving, by cable from a community antenna, the commercial TV sig- nals for local or regional retransmission. (Hence the original name for cable, CATV, for community antenna television.) In the process, CATV appropriated some of the value of the copyrighted primary broadcasts, under the assumption that operators owed nothing

New View of Copyright 1 93

to the copyright holders involved. The networks and others sued for full control over their signals and compensation for unauthorized use. Given the pending omnibus copyright revision bills, however, the Supreme Court twice declined to impose copyright liability on cable operators. The new federal law, effective in 1978, split the difference between the interests. Rather than full copyright protection and the right to deny a license to would-be users, broadcasters got a limited copyright entitlement to equitable remuneration. Rather than freedom from liability, cable operators got a right to a (compulsory) license at a price set by an obscure new agency, The Copyright Royalty Tribunal.

Thus, cable operators generally must acquire their inputs, such as satellite dishes and wiring, in arm’s length contracting with suppliers-except for rights to retransmit the basic television signals themselves, which they are entitled to purchase at a regulated price. Studies by The Rand Corporation, the Department of Commerce, and a telecommu- nications consulting firm have demonstrated various defects in this arrangement. First, Rand applied the thinking behind the Coase T h e ~ r e m , ~ which holds that economic effi- ciency is invariant to the initial assignment of property rights and liabilities as long as parties involved can bargain costlessly. Viewers could not be worse off and, demonstrably, might be better off under a system of regular proprietary rights (full copyright) rather than abridged rights. At least full copyright liability would lead to mutually consensual bargaining between program suppliers and cable systems, with the prospect that proprie- tors could impose different conditions under different circumstances and hence might be more willing to supply programming. Under compulsory licensing, transactions are invol- untary on the part of the proprietor, and hence the usual benefits of private economic transactions do not necessarily obtain! Second, the compulsory license scheme frustrates the development of “hybrid” networks-a mix of primary TV and cable-for original program distribution, as for live sporting event^.^ Third, statutory licensing unnecessarily involves the government in price-setting where multiple private licensing arrangements could be made to work? These analyses came too late, one suspects, because reversing an earlier decision is immeasurably harder than influencing one yet to be made.

Unfortunately, O’Hare comes to conclusions not especially germane to current ques- tions, such as the proper policy response to semiconductor chip “piracy” or the socially desired set of relations among television program producers, primary broadcasters, and secondary retransmitters by cable. In part the difficulty lies in his analytic model (monop- oly) and in part in his selection of examples. Without quite saying so, he seems most interested in laws or proposals to extend artists’ property rights beyond the first sale of their works. The question here is whether Jasper Johns, for example, should be encour- aged to produce paintings by receiving some percentage of the increase in the cash value of his previously sold works when they later change hands. Although this particular right may be viewed in a monopoly context, since it involves only one object of more-or-less- unique art in each case, it is not itself a major issue. Larger questions about new technolo- gies lend themselves less appropriately to a monopoly model.

COPYRIGHT, PATENT AND MONOPOLY

The limitations of the monopoly model for copyright are evident when compared with patents, which confer far more market power. A copyright confers a certain bundle of rights to its holder, led by the exclusive right to sell copies in the first instance. It does not, however, exclude independent creation of functionally similar material. A patent, by notable contrast, creates much more market power because it bars both direct copying and similar creation. For example, the inventor of intermittent windshield wipers ulti- mately prevailed in court both against auto manufacturers who used his technology without acquiring a license and against those who closely duplicated it.

94 New View of Copyright

The copyright-monopoly analysis thus fails to distinguish between the two rather differ- ent plans of legal protection for intellectual property:

Patents cover inventions (devices, processes, and compositions of matter), undergo government examination for utility, novelty, and non-obviousness, and are protected from unauthorized use or independent replication. Copyrights cover works of authorship (books, movies, dances, maps, computer soft- ware, etc.), undergo government examination only for evidence of independent au- thorship, and are protected only against unauthorized reproduction, distribution, derivation (e.g., translation), performance, and display.

Naturally, copyright confers some degree of market power; otherwise it would have no point. Just how much power depends on the availability of close substitutes. The greatest differentiation lies in the realm of culture-imaginative literature, graphic designs, mu- sic, or dance. Scribner’s does indeed have a publishing monopoly for Hemingway’s works, although it cannot bar stylistic imitators, even those proclaiming themselves Hemingwayesque! ” in cover promotions. But for the growing world of commercial infor-

mation-such as databases, software, and reference works-close substitutes are the rule rather than the exception. Where there is a dominant information service or product, it often predominates because of the high capital cost to potential entrants or the difficulty in breaking up established supplier-customer patterns. Chemical Abstracts would be a good example, one also demonstrating that copyright’s importance extends beyond for- profit corporations to not-for-profit professional organizations.

Recent business developments as well as logic show the plain differences in market power between patents and copyrights. After a ten-year legal struggle, Polaroid has forced Kodak to abandon instant photography. Kodak evidently had found no legitimate way to engineer around Polaroid’s patented technology. In contrast, Lotus Software’s copyrights on 1-2-3 and Symphony have not prevented, and indeed may have spurred, scores of other spreadsheet computer programs.

Copyright does confer much larger market power when combined with certain restric- tive licensing practices that extend the copyright’s power, sometimes unacceptably so. For instance, movie distributors originally engaged in “block booking” so that movie theaters often had to rent prints of less popular films in a package deal with highly popular ones. Some three decades ago that practice was found illegal (as “tying”) under the antitrust laws. Much more recently, however, the Supreme Court upheld similar “blanket licensing” by organizations that license the rights to perform copyrighted music. Radio and TV stations typically must pay fixed percentages of their total revenues for these blanket rights to the entire inventories of music, apparently without a meaningful alternative to bargain on a per-program or other basis. Even so, the Court viewed the practice as a legitimate exercise of collective bargaining on behalf of the music publishers, composers, and lyricists represented by the licensing organizations.

(1

THE EFFECT OF COPYRIGHT

What copyright really confers is not a monopoly but a defense against large-scale free- riders who wish to benefit from the creation and distribution of works of authorship without bearing a share of the underlying authorship cost. Consider this and other copy- righted articles in JPAM: any subscriber may read his copy-or lend it to others-as often as desired. He may also, because of the equitable statutory doctrine of “fair use,” make one copy of an article for his personal files without liability.

What readers may not do is make multiple copies or include an article in a photocopied

New View of Copyright 1 95

anthology. Such broader use requires direct permission of the publisher or payment to the Copyright Clearance Center, as indicated on every JPAM title page. And rightfully so: journals like JPAM live a financially marginal existence; to survive, they need copyright protection as well as the practice of price discrimination among users, usually frowned on in the U.S. economy. It should not be necessary to belabor the effect on scholarly, scien- tific, technical, or medical publishing if the law permitted unbridled free-rider photocopy- ing-as has sometimes been practiced at copy centers near universities. Particularly for specialized or low-circulation publications, a vicious circle would otherwise soon begin. Legitimate sales would diminish, prices would then rise, and even more photocopying would result. As a practical matter, however, publishers have been loathe to initiate legal actions against photocopiers because many suspected infringers are also primary cus- tomers. Enforcement has concentrated on large-scale photocopying, such as unauthorized anthologies produced near college campuses?

Copyright thus augments a proprietor’s marketing ability. In a capitalist society, entre- preneurs are expected to put capital at risk of market rejection in search of market rewards. One risk they cannot be expected to bear is that of unbridled free-riding. Copy- right substantially reduces that risk by providing a legal mechanism to exclude or penal- ize major nonpayers.

ALTERNATIVES TO COPYRIGHT

Even in that context, proprietors are not helpless in the face of free-riding, or “infringe- ment” as lawyers call it. They can resort to various self-defensive mechanisms. One is secrecy, with or without the support of trade secret law (which creates an intellectual property right somewhat akin to copyright). However, sellers of information can seldom rely on secrecy in the age of photocopying machines. Sellers may also employ covert defensive technology to penalize copiers. However, copy protection devices typically de- crease the utility of the product to the consumer. In the most extreme case, “worms” embedded in computer software can result in deliberate damage to the operating system of a free-rider trying to make an illegitimate copy. Copyright has the signal virtue of providing an incentive for suppliers to abandon excessive secrecy and a technological “arms race” with home computer users, for example, in exchange for disclosure and legal protection.

Pricing strategy can also diminish free-riding. Nineteenth-century U .S .-British rela- tions, alluded to by O’Hare, provide a good object lesson. No multilateral copyright treaty existed until 1886, when the principal European nations met at Berne, Switzerland; the U.S. did not sign that treaty then and has not to date, although it does belong to the Universal Copyright Convention of 1952. Moreover, the U.S. had no bilateral copyright relations with any nation until 1891, despite pressure from Britain for half a century to extend protection to British as well as American works. Even in the absence of any copyright relations, British publishers were sometimes able to sell manuscripts to a U .S. publisher before publication in Britain in return for the advantage of being first in the U .S. A modern-day strategy might be to offer advantageous multiple subscription prices, thereby forestalling the photocopying of a newsletter, for example. Yet such actions can only alleviate, not eliminate, substantial revenue losses from free-riding?

Copyright has always referred to a system of private property rights privately enforced. Congress has been pressed to respond to infringement with a more thoroughgoing rem- edy, such as an excise tax upon the retail sale of blank audio- or videotapes. Revenues would be pooled and distributed to copyright holders, a practice already followed in a number of European countries. Proponents of an excise tax have wittingly or unwittingly concealed the extent of this change in existing property rights through a misleading use of

96 1 New View of Copyright

the word “royalty.” Such payments could not be royalties because there is no content on blank tapes-that is, no protectible work of authorship. Moreover, the tax would not relate to actual use of works, only to presumed illegitimate use. The tax would really create surrogate user fees, much as the federal excise taxes on tires, motor fuels, and lubricants make motorists pay indirectly for highways. An alternative remedy now being explored is a legal requirement that recording machines include circuitry to disrupt the copying of copyrighted tapes.

THE BIG PICTURE

One’s overall concept of copyright should keep in mind its great historical success, despite the natural tendency of policy analysis to gravitate toward problems. In combination with the First Amendment, copyright-first enacted by Congress at the time of the Bill of Rights-has turned Justice Holmes’s metaphorical “marketplace of ideas” into a literal market for expression. Copyright addresses two of the chief weaknesses of a market sys- tem for information, those externalities that would otherwise prevent a seller from charg- ing for benefits that accrue to society generally (public goods) or to future generations. Fortunately, copyright protects the public interest in the free flow of information by advancing the private rights of those on whom we rely for producing this public good. More often, society must choose to advance a perceived public interest wholly by burden- ing or restricting a private property right (as in pollution control, historic preservation, and many other limits on previously unlimited private rights).

The public goal of this aspect of information policy, then, is to build on past successes. Advancing technology has called into serious question whether copyright can work as well in the future as in the past. Maybe it can’t. But the high economic and social stakes involved, copyright’s historical successes , and the lack of palatable alternatives indicate that there is no serious alternative except to try. Further amendments to the Copyright Act will be needed. Perhaps more new technology- or product-specific laws will also be needed, as for semiconductor chips, or laws based on the foundation of unfair competition as well as intellectual property. Certainly the Copyright Office must boost its ability to manage machine-readable and volatile works (for instance computer databases) as op- posed to traditional human-readable and fixed works.

This commentary notwithstanding, copyright policy cannot do without the disciplines of law and economics. It is easier to criticize their models than to improve on their contributions. Yet both seem to do better in balancing or analyzing existing property rights or economic interests than in helping to define what society wants those rights and interests to be. Perhaps a key element in such realignments is what is politically decided to be a legitimate expectation. Authors of all kinds certainly do have expectations of return from their works, as the founding fathers recognized. Congress decides how far law will embody those expectations. At the same time, users have their own sets of expecta- tions, especially about copying at home in private, which may clash with those of authors or proprietors. Because bargaining among affected parties may be costly or impractical, it may not be possible to say, on a purely economic basis, where property rights and expec- tations ought to lie with respect to such activities as home TV videotaping or home dish reception of satellite TV signals. Must broadcasters bear the cost of scrambling their satellite signals in order to exclude nonpaying beneficiaries? Or should they be able to enforce a legal right, without having to scramble? Notably, in the absence of clearly enforceable legal property rights, Home Box Office and Cinemax started scrambling their signals for pay cable TV in early 1986,9 with numerous other services set to follow by the end of the year. A strong parallel exists to privacy law, an area whose fundamental principle is the individual’s legitimate expectation. Should people using mobile telephone

New View of Copyright / 97

service have a legitimate expectation of privacy in their phone conversations? Or must they pay prices that reflect the cost of scrambling to ensure that no one listens in?

Perhaps expectations might gain greater salience in U.S. policy by way of an interna- tional agreement. American copyright policy begins with the Constitution, which em- powers Congress to grant authors exclusive rights in their writings to promote the pro- gress of science and the useful arts. Lacking such basic written law, most other advanced countries have grounded copyright policy in a theory of natural rights, as reflected in political judgments about legitimate expectations. Now before Congress is the question of whether the U.S. should finally adhere to the Berne Copyright Convention of 1886, the principal international copyright treaty, which embodies some natural law concepts. Fully bringing the U S . into the international copyright community could be the first step toward an expanded view of copyright integrating law, economics, and the politics of social expectations.

DAVID Y. PEYTON is Director, Government Relations at the Infomation Industry Associa- tion, Washington, D.C. The views expressed are his own.

NOTES

1. Michael R. Rubin, “The Copyright Industries in the United States: An Economic Report Pre- pared for the American Copyright Council,“ Washington, D.C., 1985. The five percent figure includes semiconductor chips.

2. Michael O’Hare, “Copyright: When Is Monopoly Efficient?,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Man- agement, Vol. 4, No. 3, Spring 1985, 407-418.

3. Ronald Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal o f Law and Economics, Vol. 3 (October 1960), pp. 1-44.

4. Stanley M. Besen, Willard G. Manning, Jr., and Bridger M. Mitchell, Copyright Liability for Cable Television: Is Compulsory Licensing the Solution?, The Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, R- 2023-MF, February 1977; Besen, Mitchell, and Manning, “Copyright Liability for Cable Televi- sion: Compulsory Licensing and the Coase Theorem,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 21 (April 1978), pp. 67-95.

5. Shooshan and Jackson, Inc., Cable Copyright and Consumer Welfare: The Hidden Cost of the Compulsory License, Washington, D.C., May 198 1,

6. M. Bykowsky, K . Dunmore, et al., Cable Copyright Liability: Alternatives to the Compulsory License, US. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration, April 1982.

7. On December 14, 1982, eight leading book publishers, after conducting a joint investigation through the Association of American Publishers, brought suit against New York University, an NYU faculty member, and a nearby photocopy shop. The defendants conceded liability and settled out of court. See Thomas W. Lippman, “8 Publishers Sue NYU for Alleged Illegal Copy- ing,” Washington Post, December 15, 1982, p. 1 .

8. Strategic pricing probably means that some proprietors’ groups’ claims of revenue losses due to infringement, to use the legal term for free-riding, are overstated to the extent that they multiply some number of lost sales by a fixed selling price without consideration of price-sales adjust- ments. Even so, by any reckoning the losses, especially in the Pacific Rim countries, for the US. publishing, recording, and film industries have been in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually. See Besen, Stanley M., Private Copying, Reproduction Costs, and the Supply of Intellec- tual Property, The Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, N-2207-NSF, December 1984.

9. HBO’s scrambling did not prevent a determined and resourcehl intruder from ventilating his frustration at the scrambling, which prevents backyard dish owners without decoders from free riding. In the early morning of April 27, 1986, the intruder sent a signal to HBO’s satellite powerful enough to override HBO’s own signal. For four minutes, HBO viewers east of the

98 / Comparable Worth

- COMPARABLE WORTH IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Marilyn DePoy Vandra Huber Stephen Mangurn

Mississippi saw on their screens, “Goodevening (sic) HBO from Captain Midnight. $12.95 a month? No way! (ShowtimeIThe Movie Channel, beware!).” See Richard Zoglin, “Captain Mid- night’s Sneak Attack,” Time, May 12, 1986, pp. 100-101. The action, although not a copyright offense, clearly violated the Federal Communications Act provisions against willful interference with authorized signals. The intruder, later identified as John MacDougall, a dish dealer from Ocala, Florida was fined five thousand dollars.

Using the “comparable worth” of jobs to compare wages in predominantly female versus male positions remains a controversial policy issue precisely because it lends itself to analysis by such a variety of legitimate analytical approaches with such divergent results. However, analysis seems to contribute little to the ultimate disposition of this pay equity issue, which is being resolved piecemeal within employee-employer relations, particu- larly in the public sector. These were the main conclusions of an APPAM Conference panel titled “Alternative Views on Comparable Worth.”

ECONOMISTS VIEWS

Economists’ viewpoints reflect their intellectual biases; three types are notable with re- gard to comparable worth. Neoclassical economists come at the issue with the conviction that competitive labor markets clear at wage levels that automatically register compara- ble worth: The employer discovers by trial and error what each additional worker hired adds to the total output of the organization and, for the private employer, what the sale of that output adds to the firm’s revenues. The employer then seeks to add employees until that marginal revenue product is just equal to the wage that must be paid to attract that final employee. The employer may never know exactly where that point lies but con- stantly probes toward it. Otherwise, potential profits would be forgone or losses incurred. That is the worth of the job to the employer.

In a free labor market, the employee is never forced to take a wage offer. There is a choice among jobs and a choice between any job and no job. The employee who accepts a position does so because it is more attractive than the next best alternative. The accepted wage, therefore, must be a valid measure of the worth of the job to the employee.

A wage that the employer is willing to pay and the employee willing to accept in comparison to all other alternatives must therefore be the job’s comparable worth for both. This line of reasoning takes care of the private sector. Public employers are generally required by law to pay wages comparable to the price markets. Even if not so required, public employers typically anchor their job evaluations and other decisions about com- pensation to the private market, such that no wage can depart very far or very long from the job’s comparable worth as observed in surveys of private work and wages. Thus, say neoclassical economists, no intervention is needed or justifiable. Any intervention will only detract from the total welfare of society.

Radical economists operate from a very different set of assumptions: wages are set by a combination of forces-historical, social, and political as well as economic. Women’s wages are the victims of exploitation from both the capitalist employer and the patriar- chal half of the human race. Capitalists segment labor markets in every possible way so as