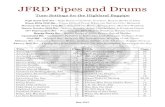

A New Compleat Theory for The Highland Bagpipe

Transcript of A New Compleat Theory for The Highland Bagpipe

A New Compleat Theory for

The Highland Bagpipe

copyright © 2020 Matthew Welch and Kotekan Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without express written permission of the author. All tunes and compositions are copyright and registered at BMI.

Cover Portrait Photo by David Welch Photography.

First published in 2020 ISBN 978-1-7356906-9-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-7356906-7-4 (PDF ebook) Printed in the United States of America

Kotekan Edition 1353 Anita Circle

Benicia, California 94510 https://www.matthewwelchmusic.com

https://kotekanrecords.comSA

MPL

E

This book is dedicated to: my parents for help with my start in piping, my wife and son who support my love for it, and those special mentors who urged me on.

SAMPL

E

CONTENTS

Foreward, by James MacHattie, College of Piping, PEI i

Preface iii

Acknowledgements iv

Part I. Treatise

Introduction 1

Chapter 1 An Organological Overview of the Highland Bagpipe 6

Chapter 2 Ceol Beag or Light Music 19

Chapter 3 Ceol Mor or Piobaireachd 37

Chapter 4 New Directions in New Millennium Piping 49

Chapter 5 New Directions in Material 63

Chapter 6 New Processes and Textures 73

Conclusion 82

Glossary 87

Bibliography 92

Part II. Music Collection

Content and Notes on the Music Collection i

Ceol Mor by Matthew Welch 1

Ceol Beag by Matthew Welch 28

Ceol Nua by Matthew Welch 45

SAMPL

E

i

FOREWARD by James MacHattie, Director of Education,

College of Piping and Celt ic Performing Arts of Canada

As bandmates and roommates for a time in the 1990s, Matt and I would have appeared to be cut from the same cloth. We played bagpipes at a high level in solos and in the Simon Fraser University Pipe Band. We were dedicated scholars of piping, composed and arranged music, and were immersed in academics. Those similarities, processed by two drastically disparate brains and mindsets, propelled us down two diverging paths. My analytical and all-too literal mind pursued academics as a career, and piping as a hobby. The end result for me was a career in piping as the Director of Education at the College of Piping and Celtic Performing Arts of Canada, and academia is now a wistful memory. Matt’s mind seemed to me to be full of cohesive chaos and inquisitive creativity. Not confined by compartmentalization and boundaries, or a strictly delineated path, his professional career unfurled naturally, entwined with his passion. He was told by Jack Lee, his piobaireachd instructor in the ‘90s, not to take liberties with the music until he had proven that he could play it conventionally. I suspect Matt interpreted this as a dare. He can deliver an achingly beautiful piobaireachd on a brilliant instrument, preserving that vein of tradition, but in this book he has also now contributed to the evolution of piping music in its standard forms, and certainly in previously undiscovered possibilities. Matt’s work puts piping into a broader context. The theoretical component appeals to a wide-ranging musical audience, without excluding traditionalist pipers and composers. The modern compositions provide glimpses into that cohesively chaotic musical brain with catchy simple melodies published alongside complicated rhythmic pieces. The modern piobaireachds are inspiring and cleverly accessible, and most of the Ceol Nua is devastatingly beyond my immediate comprehension, but the intrigue is impossible to resist. The diversity of this collection has inspired me to wander outside my self-imposed musical limits. This book is a significant contribution to piping, to the progression of traditional music, to composition, and to the exploration of entangling musical philosophies. It is brilliant, baffling, obscure, obvious, and quite simply wonderful! – August, 2020

SAMPL

E

iii

PREFACE I am pleased to finally present a publication that reflects my best thoughts on the instrument I fell in love with: The Highland Bagpipe. It has been a journey driven by an obsessive passion to learn all I can about the pipes through literature, and through hands-on tutelage from the best pipers. Early on, my curiosity for the pipes beckoned me to look beyond the music that was already there in the traditional repertoire, and so I decided to write new music for myself to play. I wrote everything from music that mirrored the tradition to other works that brought in trends from other areas of the music world.

Composition eventually drove my musical ambitions towards the environments of contemporary classical, experimental jazz, cross-cultural composition and indie-rock. Music scenes as far-ranging as Downtown New York City, to Bern, Switzerland, to Ubud, Bali were surprisingly welcome to me for similar reasons: we all were re-examining various traditional musical languages in order to express new statements.

As experimental classical, avant-garde jazz, and art-rock started to grow in the mid

20th century into their own distinct areas, away from their antecedents, many musicians were re-embracing older ideas in tonality and timbre, and many were looking across their own culture to do that. Ravi Shankar paved the way for drones in popular music, and John Coltrane’s move to the soprano saxophone called to ancient worlds to bring something back that music had lost: an overwhelming sonic-emotional impact bordering on the spiritual. Philip Glass’s amplified ensemble of electronic keyboards and winds coupled new timbre with new extended structures requiring new listening skills, and the effect of percussion and rhythmic cycles from Indonesian gamelan and African ensemble music were changing the sonic landscape of classical music. The world of art music was ready for the bagpipe.

This book includes my doctoral thesis, which dissects piping’s traditional music,

and features modern works I’ve premiered that build on or transgress these patterns. It won top-prize at Yale University’s School of Music. It should prepare the reader for Part II: a collection of my original works for the bagpipe. The Ceol Mor, Ceol Beag and Ceol Nua complement the topics of the treatise. I chose to primarily include solo music that is also functional for groups. My bagpipe concerti and other large works are on Kotekan Edition for those whose appetite is merely whetted by all here. – Matthew Welch, 2020

SAMPL

E

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to extend deep gratitude to my professors at the Yale School of Music and Yale University Department of Music, especially Dr. Sarah Weiss, with whom I primarily worked on the treatise, along with Martin Bresnick, Dr. Christopher Theofanidis, Michael Friedmann, Dr. Robert Holzer, and Dr. Paul Berry, who guided me through my both my Yale Doctor of Musical Arts and preceding Master of Musical Arts degrees. Special thanks to Dr. Rona Johnston Gordon, a native Scot and English scholar at Yale, for her tremendous copyediting and help with my creating an English tone suitable for piping’s wide reach. Special thanks to my piping colleagues James MacHattie for writing a wonderful foreward and Alan Bevan, Michael Grey and Mark Saul for contributing their supportive voices to this publication. Thank you to Chaz Stuart for valuable proofing and formatting thoughts in the Music Collection. Extra special gratitude to my wife, Ellen Jean Lueck, PhD, for the helpful tips in writing, editing and global music-scholarship. Thank you to my brother David Welch for his photo and Jonathan Johansen for the cover design. Special thanks to Lisa Bielawa, Anthony Braxton, Neely Bruce, Philip Glass, I.M. Harjito, Alvin Lucier, Michael O’Neill, Zeena Parkins, I Made Subandi, Julia Wolfe, and John Zorn for creating incredible musical opportunities for me and my bagpipe. I’m deeply indebted to all of the musicians of my New York City ensemble Blarvuster, who helped me develop much of this music and play it out in classical halls, jazz venues and rock clubs around the world from 2002 to 2020. Blarvuster is the centerpiece ensemble for five of my professional music album releases, and available on Tzadik Records and Kotekan Records. Thank you to these music groups for their enormous support in commissioning work from me repeatedly and performing it extensively: Flux String Quartet (NYC), Experiments in Opera (NYC), Jazzwerkstatt Bern (Switzerland), Music at the Anthology (NYC), Clocks in Motion Percussion Quartet (WI), Schwob School of Music/CSU Percussion Ensemble with Paul Vaillancourt (GA), Cantata Profana (NYC), Quartet Metadata (NYC) and the San Francisco Girls Chorus. Work with these groups is featured on Orange Mountain Music, Tzadik Records and Kotekan Records. Thanks to the pipers of many bands around the North America, for following me in the countless lessons, rehearsals, workshops, street gigs, and competitions. It is through nearly 30 years of teaching bagpipe music that I have refined my ideas about traditional music structure, and started experimenting pushing the envelope of the traditional music from within.

SAMPL

E

INTRODUCTION

Joseph MacDonald’s Compleat Theory of the Scots Highland Bagpipe, written in 1760 and published in 1803, is the seminal writing on the Highland Bagpipe, covering organology, fingering technique, ornamentation, a vast number of genres, and compositional technique. MacDonald was a Scottish prodigy trained in both Highland piping repertoire and classical music: he played violin, flute, and oboe and studied composition, but also traveled in Scotland studying with piping masters.1 MacDonald’s book, the first of its kind, is marked by his ability to both analyze and notate orally transmitted tunes. With his foot in two musical worlds, his analytical perspective was broad, and he had a sensitivity that allowed him to find fine examples of Highland repertoire to illustrate his points. MacDonald employed a wealth of vocabulary that includes Gaelic and Italian musical terms to categorize genres by both the general and specific features of their affects. Lacking the benefits of the metronome, MacDonald sought to describe tempo with the methods available to him; his employment of Italian tempo markings to categorize tempo structures used by pipers was highly innovative. He denied, however, any significant use of Italian-derived repertoire, remarking that to adapt contrapuntal repertoire for a drone instrument whose articulation is emphatically idiosyncratic could only produce remarkably insipid or awkward results. He noted that by contrast the instrumental folk music of Scotland was readily absorbed into the piping idiom. For MacDonald, however, the system of ornamentation and the melodic sensibility of Highland pipe music were already extremely rich.2 The terms he associated with distinct types of tunes and ornaments allowed him to produce the first theorized prose to document the multitude of structures within Highland pipe music.

The overview of approaches to pipe music provided by this essay seeks to be a Compleat Theory for today, a broad, comprehensive, insightful yet succinct account of the Highland Bagpipe repertoire, with examples drawn from the rich repertoire that stand out as compositionally didactic or masterfully original. Today the piping spectrum extends across piobaireachd (the “classical” music of the pipes, of which we will hear much), light music (competitive or not), and kitchen piping to pipe band innovations and use of the instrument in art music. Although pipe music is solidly grounded in the music of the past, today composers find ways of loosening those ties and making the repertoire more

1 Roderick Cannon, ed., Joseph MacDonald’s Compleat Theory of the Scots Highland Bagpipe (c. 1760) new edition with introduction and commentary (Glasgow: The Piobaireachd Society, 1994). 2 Cannon, Joseph MacDonald’s Compleat Theory, 76. See also MacDonald’s lengthy discussion in the chapter entitled “Observations on the Proper Style of this Instrument.”

1

SAMPL

E

contemporary. The dialogue between compositional method and the conventions of the bagpipe in which an art-music composer can participate creates a commentary on the reworking of tradition. Composers’ unique decisions suggest possibilities for the instrument that the inertia of the existing traditional repertoire had left unfulfilled. My goal is to create a Compleat Theory that captures the incisiveness of MacDonald’s work but is also thoroughly modern. This formal overview of the kinds of musical composition that have been applied to the bagpipe will equip a composer who wishes to consider idiomatic practice as she or he works on new bagpipe music. This imagined composer is not a fixed type but might be, for example, a piper who wishes to include more diverse motives in his or her tunes or an art-music composer minded to compose for the bagpipe but confronting the instrument for the first time. That composer’s understanding of what is idiomatic for the pipes can be shaped by examples that highlight the structure of bagpipe music. The performer, too, will benefit from a more comprehensive understanding of the structural and aesthetic concerns of the repertoire, and this essay seeks also, therefore, to provide performers with a frame of reference as they engage with new music projects. A Piper and a Composer The Highland Bagpipe has long been central to my musical interests. Even while still young, I absorbed much of the available literature on Highland bagpipe music as I studied the instrument and its repertoire within the oral tradition, but at that stage my interest was above all performance based. Over the years I have been very fortunate to be able to study with so many talented players at the forefront of competitive piping, including gold medalists and master players such as James MacIntosh M.B.E., Colin MacLellan, Mike Cusack, Angus MacLellan, Andrew Wright, Iain MacLellen B.E.M., Terry Lee, and Jack Lee, with whom I worked extensively. I became very involved in solo competition and advanced to professional open level within five years of starting playing, but simultaneously I also participated in Pipe Band competitions. Playing in ensembles composed of bagpipes and drums requires great discipline if all instruments are to sound together. A highlight of my competitive Pipe Band playing was as a member of one of the premier (Grade 1) bands of the last twenty years, the Simon Fraser University Pipe Band, of which I was a member when it won the World Pipe Band Championships in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1999 and 2001. My appetite for bagpipe music was voracious. I learned repertoire very quickly but also had started analyzing tunes and composing in the idioms discovered in my early playing days. My interest in composing blossomed within the realm of piping culture, fed initially by a desire to understand the syntax of the music but finding in the pipes a very gratifying focus of creativity. Having added composition to oral instruction and my reading of all the available literature, I felt I had cracked the codes of Highland Bagpipe music.

2

SAMPL

E

For twenty years I have been a teacher of Highland Bagpipe music, distilling and re-synthesizing what I have learnt and continue to learn from oral and written sources. The ability to convey theory has proved crucial in helping players comprehend and re-articulate the musical architecture of a tune, in particular for pipers who lack easy and regular access to piping music. Group cohesion, especially in a large group, is impossible if the performers lack a clear sense of the structure of the music they are performing. The New York Metro Pipe Band and other pipers and bands in the piping-rich diaspora of the New York metropolitan area have been under my tutelage for over ten years. New York Metro won a Grade-3B World Championship and a Grade-2 North American Championship in 2011 and 2012 respectively. All these experiences have supported my developing awareness of how pipe music functions and how a player can articulate these functions within the competitive performance environment. Additionally my practical and theoretical engagement with piping allows me to highlight what masterful or inspired inventions propel the idiom from within the tradition.

My compositional interests and musical knowledge expanded further when I began listening to and studying contemporary art music in high school. I was keen to explore how some of the new techniques of musical organization could be transferred into the context of a piping tune. I chose to pursue degrees in music composition as bagpiping was not offered in most music schools. My formal musical education developed side by side with my piping life, each reinforcing the other.

As a piper with additional training as a composer, I was well positioned to participate in the making of avant-garde bagpipe music and extended the repertory as both performer and composer. I developed extended techniques for the instrument. I performed Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’ Orkney Wedding with Sunrise with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. With my encouragement and collaboration Michael O’Neill, Alvin Lucier, Anthony Braxton, and Julia Wolfe composed in unique ways for the bagpipes, and I was very fortunate to premiere their work, and the new music of many others for pipes such as Zeena Parkins, David Watson, Neely Bruce, I.M. Harjito, Sumarsam, I Made Subandi, and Robinson McClellan. I was also writing my pipes into my own compositions, testing compatibilities, stretching expectations, and exploring new realms. Challenging Terms I am not the first to theorize about piping and its musical forms. But I am the first composer of American new music with deep knowledge of piping and piping traditions to write a manual about piping techniques and piping melody forms. My goal in this work is to provide a thoroughgoing explication of piping that will be useful for other teachers as well as for composers who hope to write music for the Highland Bagpipes. In essence, this

3

SAMPL

E

essay will provide composers with a toolkit from which they can create playable new music for pipers alone and in various ensembles. Composers of art music and players of pipes talk about music in equally studied and yet very different ways. My objective is to create a middle ground where terminology is comprehensible to both piper and Western composer. The challenge is significant. Many piping terms are in Gaelic, and it is all too easy for those without that language to be alienated by its repeated use. My goal is not to provide terms that might be memorized but to use these terms as vehicles that express ideas, at times abstract, about the function or systematic construction of musical devices. A glossary is included here as an aid, although pipers or composers for the pipes will need, and indeed I hope relish, their growing familiarity with these expressions.

Some piping terms are in English, which has its own problems. Similar terms are sometimes used in other musical prose but with a different meaning. And sometimes traditions use different terms to refer to similar abstract musical effects. I use terminology from both traditions, selecting the term that best represents the technical, structural, poetic, or specifically Highland feature in the music at hand. Since Highland Bagpipe music was reasonably codified by the twentieth century, certain names, categories, and ideas of structure can be drawn from that environment, where otherwise we might have to have recourse to European or Western counterparts. Where both terminology pools are relevant, I draw from both. Where a point or concept is best framed in the terminology common to Western art music composers, I use it with a brief description for non-specialists. When I examine new works by art-music composers, the terminology I employ reflects the directions taken in the compositions themselves, which employ non-Highland concepts often drawn from Western musical procedures. Chapter Structure This essay isolates compositional choices and procedures that shape bagpipe music. Its six chapters are structured to give a sequence to these choices that leads into increasing complexity (and perhaps difficulty for the player) and increasingly individualized composition. The first chapter provides a primer on the Great Highland Bagpipe and its sonic resources and basic articulation methods. This section covers instrument construction, common scale organization, and the essence of articulation and ornamentation. Chapters two and three provide the basic building blocks of structure, genre, meter, and rhythm in ceol beag, or light music, and ceol mor, or great music (another term for piobaireachd), making use of historical notation in order that its typography can communicate something of its time and practice. Chapter four documents innovation in compositional practice within the idioms in the course of the twentieth century, including “kitchen piping.” Chapters five and six consider the use of the bagpipe in

4

SAMPL

E

experimental composition and suggest effective new parameters of sound organization that can be applied to new works.

This essay draws on my many years of practical experience and scholarly engagement with the pipes. Most of the books in my bibliography are the well-loved companions of a developing performer and composer. Of particular note, and indeed my old favorites, are Roderick Cannon’s The Highland Bagpipe and Its Music (1988), Seumas MacNeill’s Piobaireachd: Classical Music of the Bagpipe (1968), and Seumas MacNeill and Frank Richardson’s Piobaireachd and Its Interpretation (1987). The collections of the Queen’s Own Highlanders regiment (now out of print) and John MacLellan’s classic version of Logan’s Complete Tutor for the Highland Bagpipes (1976) make for interesting primary sources as they give a sense of the material to which pipers have access. They also document a mid-twentieth century take on Scottish language that now appears quaint and a unique approach to European notation.

Piping today is predominantly about light music, made more popular when played by pipe bands; the Highland bagpipe rarely appears in an art music composition.3 But the repertoire is growing and becoming ever more stylistically varied, as composers of art music or experimental music integrate the bagpipe in ways that usually involve a departure from convention to fit their personal voice. This essay will provide such composers with a map to help them toward that goal.

3 William Donaldson, The Highland Pipe and Scottish Society, 1750-1950, Transmission, Change and the Concept of Tradition (East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell Press, 2000).

5

SAMPL

E

A New Compleat Theory

for The Highland Bagpipe

Part II

Music Collection

49 original works of Ceol Beag, Ceol Mor and Ceol Nua

for the Highland Bagpipe

By Dr. Matthew Welch

KOTEKAN EDITION 2020 SAMPL

E

About the Music Collection This music collection is intended to be a companion to the treatise. Together, their ideas reflect two parts of a whole, in that mostly my personal interpretation of traditional piping has lead me to both analyze what I encounter in this way, and because of that, I compose with some of these extra topics in mind. The music here isn’t analyzed in the treatise per se, however the analyses there will give the player deep insight into the compositions in the collection. I have where possible made the tune titles and the music therein tell the stories themselves.

Music Collection Contents Piobaireachd The Boatman at Sea 2 Farewell to Bali 1 For Colin Newlands 4 For Fear That My Shadow May Enter the World 6 The Garden of Forking Paths 8 Lament for the Children of Sandy Hook 12 Lament for Grandfather Donald 14 Lament for Lost Love 17 Lass at Castle Urquhart, Be My Bride 18 Looking at Loch Fyne 20 Mother’s Praise 22 Salute on the Birth of Mason Reid 24 Sing Me to Sleep 26 CEOL BEAG Marches Andrew Bonar’s March 28 The Queensborough March 29 The Brown Beastie’s Plunge Over the Great Divide 30 Reels The Academic Quadrangle 31 Adam Quinn’s Reel 32 Avant-Garde Onsgard 32 Bottom’s Up 33 Grumpy’s Reel 33 High Street Reel 33

J igs Eskbank House, Inverness 34 Ellen Jean’s Jig 34 Maximilian the Operatic Parrot 36 Keen John 35 The P-Vone Zone 35 Sideways Man 36 Yogic Flying Glen 34 Hornpipes Butter Fingers (Balkan-Hornpipe arr) 37 Gorgamor the Giant Gecko 38 High Street Hornpipe 40 The Labyrinths of Borges 42 Pak Gusti Aji 41 Sophie’s Dance 44 Ceol Nua Sonata for Bagpipe 45 Selections from Traversing Mad-hatten 2nd Street 50 3rd Street 51 4th Street 52 5th Street 53 6th Street 54 7th Street 55 1st Avenue 56 3rd Avenue 57 Duo-Duel 58 Gorgamor the Giant Gecko (score) 59 The Off-Kilter Mason 64

All compositions published by Kotekan Edition are copyright Matthew Welch, registered with Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI).

SAMPL

E

Notes on Ceol Mor I started composing Piobaireachd in high school, inspired by books, people and world events. I wanted to create new works to play on my pipes that explored these ideas. Many of the tunes here were written when I was an intense solo Piobaireachd competitor and member of the Simon Fraser University Pipe Band, studying classical music composition and looking for a future creative niche in my piping. Some of these tunes I played at recitals and some I repurposed for my compositions for classical instruments. They were composed with the utmost earnestness, with a true love for Ceol Mor form and style, especially the innovative motifs and variations of the most celebrated traditional tunes. Some tunes are suitable for novice and intermediate players, while some will challenge the top professional. All are built on melodic foundation guided by my own singing, playing and studying of Piobaireachd, with a dash of influence from some the other musics I’ve been involved in. Because the tunes are new, no Urlar contains any shorthand symbols for the ornamentation, to dispel any ambiguity. Some embellishments are new, but built on or close to traditional Ceol Mor technique. Where an embellishment occurs frequently in a variation, appropriate abbreviations have been provided in line with current practices in the Piobaireachd Society Collection and Kilberry Book of Ceol Mor.

About the cadence grace-note groups: These are written in a new way as to consolidate the variety of previous notational and performance approaches found throughout historical settings of the traditional repertoire. I double-stem certain grace-notes to indicate that it may be played short or long: They may be played anywhere along the spectrum of historical rhythms informed by manuscripts of Joseph MacDonald, Donald MacDonald, MacArthur-MacGregor, MacKay, Glen, Ross, etc: as a cascade of even grace-notes or with an elongated E (or F) grace-note with melodic value (a la Binneas is Boreraig), depending on the preferred playing style of the piper. Perhaps it is logical that one approach be chosen and made consistent throughout a performance, but no means is that absolutely necessary. If the player chooses more historical performance approaches, additionally any “double-echo” movement, here written as per current practice, may be played with its dotting reversed to reflect the older practice. One may ask, why should one play new tunes in an old style, or what worth do these tunes have to an authentic traditional player? My answer is that piobaireachd practice, new or old, is one of the more imaginative ventures of Highland piping expression, and should continue to be a cradle of creativity. My conjecture is that back in the day one could extemporize in piobaireachd more, which research confirms. One decidedly new formal aspect to piobaireachd is the abundance of choice for the player in building their performance of the tune The Garden of Forking Paths. Go forth and play creatively!

& # # ..JœærKœ œ Jœæ

rKœ œD. Taorluath 1 Doubling

Jœæœ

Jœæœ Jœæ

rKœ œ JœærKœ œ Jœæ

œJœæ

œ

& # # JœærKœ œ Jœæ

œJœæ

œJœæ

œ JœærKœ œ Jœæ

œJœæ

œJœæ

œ

& # # JœærKœ œ Jœæ

rKœ œ Jœæœ

Jœæœ

JœærKœ œ Jœæ

rKœ œ Jœæœ

Jœæœ

& # # 42 ..œ œU

œJ œ rKœ .œ œ œ œ œ œT

E. Taorluath 2 Singling

œ rKœ œU œT

œ œU

œJ œ œT T

œ rKœ œUT

& # # œ œU

œJ œ œT T

œ rKœ œU œT

œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ rKœ œ œ œœ

œœU œ rKœ œU

T

& # # œ œU

œJ œ œT T

œ rKœ œUT

œ œU

œJ œ œ œ œ œ Jœ œ3

T

rKœ œ œ œ rKœ œU

& # # ..œ œU

œJ œ rKœ .œ œ œ œ œ œT

F. Taorluath 2 Doublingcadence first time only

œ rKœ .œ œ œ œ œ œT

œ œT T

œ œT T

& # # œ œT T

œ rKœ .œ œ œ œ œ œT

rKœ .œ œ œ œ œ œ œT

œ œT T

& # # œ œT T

œ œT T

œ œT T

œ œT T

The Garden of Forking Paths

SAMPL

E

Notes on Ceol Beag Much of the Ceol Beag served me as recital tunes, tunes for my pipe band medleys, fodder for chamber compositions and especially material for my own New York City-based ensemble, Blarvuster. Many of these tunes can fit well together just based upon their consistent style of additive rhythmic groups and contours that play with and against the pulse and meter, and their exploration of newer scale groupings. Their juxtapositions and transitions are fairly compatible depending on the overall desired harmonic direction of a medley or session. Many of them reflect my studies in other areas of music, such as Balinese gamelan, and hybridize music from all over the globe with the idioms that pipers already grasp. These tunes may be “re-graced” to fit other instrumentalists’ or pipers’ needs, however I chose to set them the way I play them most of the time. Notes on Ceol Nua Ceol Nua (New Music) is a term I coined to describe my compositions that specifically hybridize aspects of traditional piping music with motifs, structures and procedures from avant-garde and classical music. My first step in this direction was my Sonata for Bagpipe, written while a composition student and piper at Simon Fraser University. It is built directly around the repetition, gradual change and additive structures found in Minimalist music, particularly that of Philip Glass, who I had met, discussed my ideas, and got me fired up to do something new. The numerous pieces of Traversing Mad-hatten, named after the easy-to-navigate streets and avenues in New York City. They each require an element of musical improvisation with the instructions set forth, and so they are musically renewed with each performance. They are designed to be played with user-controlled flexibility in a new form of medley playing, where one can move between pieces as one plays with the ease of modern travel (e.g. subways), in the execution of an extended creative performance. Duo-Duel, for two pipers, similarly free from a set form, yields various possible outcomes limited only by the design of the musical topic; a sort of chase. These were composed very much in the ideas of John Cage and my mentor, avant-jazz master Anthony Braxton, who I studied composition with at Wesleyan University. The score for the “Blarvuster version” of Gorgamor the Giant Gecko is included to show how I set the hornpipe version (in the Ceol Beag section) into a song-structure with unique counterpoint and drum set part for my NYC-based ensemble Blarvuster. This Eb Major/Bb Mixolydian score illustrates the music at concert pitch. Performers are encouraged to make arrangements for their own ensembles, with or without pipers! A good tune is a good tune on any instrument, I hope! The most recent Off-Kilter Mason, for my son learning to walk, is an attempt to combine many of the metric idioms and song forms found in the many music traditions I love.

SAMPL

E