A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

-

Upload

dividedistand -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

1/16

A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in

major depressive disorder

Lauren M. Bylsma, Bethany H. Morris, Jonathan Rottenberg

Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Ave, PCD4118G, Tampa, FL 33620, United States

Received 14 April 2007; received in revised form 30 September 2007; accepted 3 October 2007

Abstract

Three alternative views regarding how Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) alters emotional reactivity have been featured in the

literature: positive attenuation (reduced positive reactivity), negative potentiation (increased negative reactivity), and emotion

context insensitivity (ECI; reduced positive and negative reactivity). Although empirical studies have accumulated on emotional

reactivity in MDD, this report is to our knowledge the first systematic quantitative review of this topic area. In omnibus analyses of

19 laboratory studies comparing the emotional reactivity of healthy individuals to that of individuals with MDD, MDD was

characterized by reduced emotional reactivity to both positively and negatively valenced stimuli, with the reduction larger for

positive stimuli (d= .53) than for negative stimuli (d= .25). Results were similar when 3 major emotion response systems (self-

reported experience, expressive behavior, and peripheral physiology) were analyzed individually. The ECI view of emotional

reactivity in MDD is well supported by laboratory data. Implications for the understanding of emotions in MDD are discussed.

2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Major depression; Emotion; Affect; Reactivity; Meta-analysis

Contents

1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 677

1.1. Views of emotional reactivity in MDD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 678

1.2. Limitations of prior reviews . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 678

1.3. The present study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6792. Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 679

2.1. Overview. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 679

2.2. Rationale for emotion response domains covered in this review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 679

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

The authors express their appreciation to Michelle Jones for her help in library research and to the members of the Mood and Emotion Laboratory

for their comments. This research was supported by a University of South Florida New Researcher Grant awarded to Jonathan Rottenberg. Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 813 9746701; fax: +1 813 9744617.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (L.M. Bylsma), [email protected] (B.H. Morris), [email protected] (J. Rottenberg).

0272-7358/$ - see front matter 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001

mailto:[email protected]:[email protected]:[email protected]://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001mailto:[email protected]:[email protected]:[email protected] -

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

2/16

2.3. Variables included in this review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 680

2.4. Literature search . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 680

2.5. Study inclusion criteria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 680

2.6. Characteristics of selected studies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 681

2.7. Computation of effect sizes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 681

2.8. Planned analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 683

3. Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 684

3.1. Omnibus analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 684

3.2. PER and NER in individual response systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 685

3.2.1. PER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 685

3.2.2. NER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 685

3.3. Heterogeneity and Moderator Analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 685

3.4. File drawer analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 686

4. Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 686

4.1. Limitations and future directions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 687

4.2. Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 688

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 688

1. Introduction

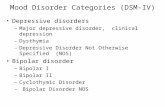

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a debilitating condition that afflicts almost a sixth of the general population

(Kessler, 2002). Reflecting the profound disturbance of affective function in MDD, it is classified as a mood disorder

by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; APA, 2000). DSM-IV diagnostic criteria

specify symptoms of at least two weeks duration that implicate deficient positive affect (e.g., anhedonia), excessive

negative affect (e.g., guilt, sadness), or both. When queried, patients who have been diagnosed with MDD reliably

report low positive affect and elevated negative affect on a variety of questionnaire and interview measures ( Clark,

Watson, & Mineka, 1994). Durable disturbance of mood is thus one of the most salient features of MDD.

Given that MDD is quintessentially a disorder of mood, one important question is how MDD influences emotional

reactions. Addressing this question requires a distinction between the constructs mood and emotion (e.g., Rottenberg &Gross, 2003). Moods have been defined as diffuse, slow-moving feeling states that are weakly tied to specific stimuli in

the environment (e.g., Watson, 2000). By contrast, emotions have been defined as quick-moving reactions that occur

when an individual processes a meaningful stimulus (e.g., a threatening object). Emotional reactions are multi-

componential and typically involve coordinated changes in several response systems (e.g., perception, feelings,

expressive behavior, peripheral and central physiology; Ekman, 1992; Keltner & Gross, 1999). When mood and emotion

are so distinguished, it becomes apparent that the various diagnostic criteria for MDD, such as pervasive sadness or

anhedonia, indicate alterations in mood, but do not indicate alterations in emotion with corresponding specificity.

Although the constructs are distinguishable, moods and emotions have generally been seen as interconnected, with

moods altering the probability of having specific emotions (e.g., Rosenberg, 1998). More specifically, moods are

thought to potentiate like-valenced or matching emotions (e.g., irritable mood facilitates angry reactions, an anxious

mood facilitates panic, etc; Rottenberg, 2005). By extension, excessive negative mood in MDD would potentiatenegative emotional reactivity and/or a lack of positive mood would attenuate positive emotional reactivity. Indeed, the

idea of mood-facilitation is one guiding source for three major views regarding emotional reactivity in MDD: (1)

negative potentiation (2) positive attenuation and (3) emotion context insensitivity (ECI). We will briefly outline each

of these views before presenting a meta-analysis designed to determine which of them best fits the accumulated data

concerning emotional reactivity in MDD.

Our main goal was to conduct a systematic meta-analytic review of the literature on emotional reactivity in MDD.

We used rigorous literature search strategies (see below) to identify laboratory studies of emotional reactivity in MDD

and estimate effect sizes. We report effect sizes from 19 laboratory studies that compared negative and positive

emotional reactivity between individuals with MDD and healthy participants. Analyses focused on omnibus group

differences in positive and negative emotional reactivity, as well as the replicability of these group differences within

three specific emotion response systems: self-report, behavioral, and peripheral physiological reactivity. To our

knowledge, this study represents the first meta-analytic review of the literature on emotional reactivity in MDD.

677L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001 -

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

3/16

1.1. Views of emotional reactivity in MDD

Negative potentiation, the first view, holds that the pervasive negative mood states that are prevalent in MDD

contribute to potentiated emotional reactivity to negative emotional cues. Perhaps most relevant to the idea that

negative moods and negative emotions are mutually reinforcing in MDD, cognitive theorists see negative moods as

facilitating negative cognitive processing which, in turn, results in negative cognitive interpretations that generatedysphoric reactions (e.g., Beck, 1976; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). Beck's schema model and related theories

of depression (e.g., Bower, 1981) conceptualize MDD in terms of cognitive structures, or schemas, which are patterns

in thinking that serve to negatively distort the processing of emotional stimuli (e.g., such as beliefs that one is unlovable

or a failure). Importantly, according to these theories, negative mood states prime, or activate, these cognitive structures

(Scher, Ingram, & Segal, 2005). Once activated, these structures precipitate negative interpretations which give rise to

depressotypic emotional responses (e.g., crying spells) whenever schema-matching negative emotion stimuli are

encountered, presumably potentiating reactivity to negative emotional stimuli in MDD.

Positive attenuation, the second view, holds that individuals with MDD will have reduced reactivity in response to

positive emotional stimuli. Because this hypothesis applies primarily to positive emotional stimuli, positive attenuation

is compatible with negative potentiation (i.e., individuals with MDD can exhibit both patterns simultaneously). The

starting point for this hypothesis is the depressed persons' strong tendency to exhibit low positive mood. Indeed,anhedonia (the reduced ability to experience pleasure) is one of the cardinal symptoms of MDD, and depressed

individuals exhibit several other signs that are also indicative of deficient appetitive motivation (e.g., psychomotor

retardation, fatigue, anorexia, apathy). Not surprisingly, several theorists have centered their accounts of abnormal

emotional responding (e.g., abnormally low emotion response magnitude) in MDD on this constellation of

motivational deficits (e.g., Clark et al., 1994; Depue & Iacono, 1989) often focusing on the central nervous system

substrates for deficient appetitive motivation (e.g., hypoactivation in the left frontal lobes; Henriques & Davidson,

1991).

Emotion context insensitivity (ECI), the third view, holds that depressed individuals will exhibit reduced reactivity

to all emotion cues, regardless of valence (Rottenberg, 2005, 2007). By this account, individuals with MDD should

exhibit less reactivity to both positive and negative stimuli and events compared to healthy individuals. ECI is derived

from evolutionary accounts that describe depression as a defensive motivational state that fosters environmental

disengagement (Nesse, 2000). According to this view, depressed mood states evolved as internal signals to biasorganisms against action in adverse situations where continued activity might be potentially be dangerous or wasteful

(e.g., famine). Thus, according to ECI, severe depressed mood states in MDD are postulated to inhibit ongoing

emotional reactivity. In sum, ECI makes similar predictions as the positive attenuation view for positive stimuli, but

makes opposite predictions as the negative potentiation view for negative stimuli.

1.2. Limitations of prior reviews

Prior generalizations about emotional reactivity in MDD have been based on narrative reviews, which can be

susceptible to selection biases and are often unsystematic in their search strategies. Any review also faces the

complexity of operationalizing the major constructs relevant to this topic area. For example, the depression construct

can be operationalized in different kinds of samples (e.g., analogue samples of dysphoric persons versus case-levelMDD), and even studies of MDD may consider related conditions, such as dysthymia or minor depression, to be part of

the depression construct. Thus, reviews may describe different effects of depression on emotional reactivity because

different kinds of depressive phenomena are being considered. Likewise, complexity in the emotion construct also

complicates the task of review. Emotional reactivity can be operationalized in a large number of response systems,

which often exhibit considerable independence from one another (e.g., self-reported experience, expressive behavior,

cognition, peripheral nervous system responding, or neural activity, see Mauss, Levenson, Carter, Wilhelm, & Gross,

2005). Prior reviews have not made a concerted effort to integrate data across self-report, behavioral, and physiological

domains (e.g., Forbes, Miller, Gohn, Fox, & Kovacs, 2005; Gehricke & Shapiro, 2000). Further, even within any given

system of response, emotional reactivity can be computed using different metrics (e.g., level scores versus change

scores), and commentators have generally not been explicit and/or systematic in defining their choice of reactivity

metric. Given these multiple challenges, perhaps it is not surprising that prior narrative reviews in this area of research

have been inconclusive.

678 L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

4/16

1.3. The present study

To overcome the limitations of prior reviews, we assessed the literature on emotional reactivity in MDD using

meta-analysis an important quantitative technique for systematically summarizing results across different

studies which use different measurement techniques and arriving at stable estimates of effect sizes (Cohen, 1988).

In contrast to narrative reviews, meta-analysis avoids reliance on statistical significance tests and provides precisequantitative estimates of the magnitude of effect sizes. For this meta-analysis, only studies that elicited emotion in

a well-controlled manner and used DSM diagnostic criteria for MDD were included. Analyses focused on the

extent to which MDD might increase or decrease positive and negative emotional reactivity relative to healthy

individuals.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

A meta-analytic procedure was used to estimate the effect of MDD on emotional reactivity. Our major focus was on

positive emotional reactivity (PER; i.e., emotional reactivity to a positively valenced stimulus) and negative emotionalreactivity (NER; i.e., emotional reactivity to a negatively valenced stimulus). Emotional reactivity was defined as a

positive (PER) or negative (NER) measured emotional response to a matching emotionally valenced stimulus that is

reflected as a change from baseline affect. We focused on these two forms of emotional reactivity rather than specific

emotions because (1) the major views of emotional reactivity in MDD concern PER and NER (2) valence has high

theoretic importance in the emotion literature (e.g., Barrett, 2006), and (3) insufficient research exists to allow pooling

of results for specific emotions.

2.2. Rationale for emotion response domains covered in this review

One general challenge in conducting a meta-analysis of PER and NER is the overwhelming number of responses

that are potentially relevant to emotion. Relatedly, there is a lack of consensus among affective scientists regarding just

how many emotion response systems there are, and how all of these response systems should be mapped on to theemotional reactivity construct (e.g., posture, touch, perceptual changes, Rottenberg & Johnson, 2007). To make this

problem more tractable, we made a judgment to focus our review on three response systems that are important to

emotional reactivity: (1) behavioral/expressive, (2) experiential/subjective, and (3) peripheral physiological responding

in the autonomic nervous system. These three systems were prioritized for four main reasons: First, these three systems

have been historically important in guiding inquiry in emotion (e.g., Dolan, 2002; Ekman, 1992; Lang, Rice &

Sternbach, 1972; Lang, 1988; Lazarus, 1991; Levenson, 1994). Second, there is reasonably good agreement that these

three systems do in fact index emotional reactivity. Third, there is reasonably good agreement on measures that can be

extracted from these systems to index emotional reactivity (see below). Fourth, there is an adequate database of

empirical studies using metrics from these three systems in MDD to conduct a meta-analysis.

Although a focus on these three systems affords our review some breadth as well as some fidelity to the construct of

emotion, this review is by no means all-inclusive of systems that are relevant to emotion. Perhaps most importantly,neurological and endocrine systems play a major role in emotional reactivity (e.g., LeDoux, 1998). However, we did

not include neuroimaging metrics (e.g., techniques such as fMRI, PET, and ERP), because existing reviews of

neuroimaging and emotion indicate that considerable disagreement remains about how to map emotional reactivity

onto these techniques (e.g., Murphy, Nimmo-Smith, & Lawrence, 2003; Phan, Wager, Taylor, & Liberzon, 2002).

More practically, an early inspection of potentially relevant studies indicated that imaging studies of MDD did not

routinely report statistics needed for computing effect sizes. Further, the technical problems of conducting meta-

analytic analyses of neuroimaging data are considerable, as these are far from simple computations of effect sizes,

and, typically, effect sizes based on standardized mean differences cannot be calculated due to the complexity of the

data, and because the focus is typically on activity location rather than effect size ( Fox, Parsons, & Lancaster, 1998).

Fox et al. (1998) have noted that meta-analytic procedures do not provide an adequate way of combining

neuroimaging and non-neuroimaging measures into a single meta-analysis for both methodological and theoretical

reasons. For these reasons, separate meta-analytic procedures must be used for neuroimaging data that have different

679L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

5/16

theoretical interpretations. Likewise, we did not consider the domain of cognition to be tractable for our purposes,

even though cognition and emotion interact (e.g., Gray, 2004), and cognitive changes are among the known correlates

of emotional reactions. An inspection of the literature suggests that cognition is extraordinarily heterogeneous as a

domain, and that there is little agreement or precedent concerning how metrics from the cognitive domain (e.g.,

memory bias, perceptual judgments, reaction times, etc) should be mapped onto the emotional reactivity construct for

meta-analysis.

2.3. Variables included in this review

Selection of measures of emotional reactivity within the three response systems covered in this review (self-reported

experience, expressive behavioral, and peripheral physiological) was guided by prior literature demonstrating that each

measure could be interpreted as a valid index of emotional reactivity. Self-report measures of emotional responses

included subjective reports of emotional experience through various self-report measures such as the PANAS (Watson,

Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), the SAM (Bradley & Lang, 1994), or discrete emotion measures. Behavioral measures

included observed facial expression as measured through facial coding systems (e.g., FACS; Ekman, Matsumoto, &

Friesen, 2005; Lang, Greenwald, Bradley, & Hamm, 1993) or electromyographic (EMG) recordings of the face (e.g.,

Cacioppo, Martzke, Petty, & Tassinary, 1988; Cacioppo, Petty, Losch, & Kim, 1986; Lang et al., 1993 ), emotion-modulated eyeblink/startle responses (e.g., Bradley, Cuthbert, & Lang, 1999; Bradley & Lang, 2000 ), and approach/

avoidance behavior (e.g., Carver, 2001; Henriques & Davidson, 2000). Physiological measures included measures of

autonomic peripheral physiology, specifically including skin conductance responses (SCR; e.g., Lang et al., 1993),

heart-rate variability (HRV)/respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) (e.g., Appelhans & Luecken, 2006; Butler, Wilhelm, &

Gross, 2006), blood pressure (e.g., Melamed, 1987), respiration (e.g., Ritz, Thons, Fahrenkrug, & Dahme, 2005), heart

rate (e.g., Lang et al., 1993), and finger pulse amplitude (FPA; e.g., Gross, 2002).

2.4. Literature search

This review covered published journal articles in the English language since 1975. Only published articles were

reviewed for possible inclusion, because published work generally has increased scientific rigor compared with

unpublished work, and because it is readily available within the public domain for independent evaluation by others.Because null results may be more difficult to publish than significant findings (potentially leading to upward biases of

effect sizes in the published literature), we included file-drawer analyses to provide an estimate of the number of

studies with non-significant results that would be necessary to alter the interpretation of the primary results ( Rosenthal,

1991).

To generate potentially relevant articles, the first author used the PsychINFO and MEDLINE online database,

entering the following keywords: depress and emotion reactivity, depress and affect modulation, depress and

affect regulation, depress and emotion functioning. The wildcard was used to ensure that all forms of the

keywords were searched. After identifying potentially relevant articles, the reference sections were searched to identify

additional articles which might meet our inclusion criteria. As an additional check to ensure that no relevant articles

were omitted, a research assistant also performed a parallel search.

2.5. Study inclusion criteria

Articles were required to meet the following inclusion criteria (a) a group of participants that qualified for a

diagnosis of current MDD using DSM criteria (b) a healthy control group, (c) appropriate statistics (e.g., means and

standard deviations) that were reported in the published article or available from the author upon request (of nine

articles that were missing data, the study authors were able to supply it in six cases), (d) measured emotional reactivity

with self-reported experience, expressive behavioral, or peripheral physiological indicators (e) a positively or

negatively valenced emotion elicitation condition was included, along with (f) a neutral or baseline condition to allow

computation of NER and PER (without a baseline of comparison responses to a valenced stimulus may reflect a general

disposition or mood rather than reactivity to a given stimulus). Medication use by patients was not considered as an

inclusion/exclusion criterion because virtually no studies in the entire literature used an un-medicated sample (our

search yielded only four such studies).

680 L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

6/16

2.6. Characteristics of selected studies

From an initial screening, a total of 35 potential articles were found. However, 6 of these did not include a control

group, 4 did not include a neutral or baseline measure, 2 were not laboratory studies, and 3 did not include the necessary

means and/or standard deviations for inclusion in the meta-analysis and the authors were unable to be contacted. The

final sample for inclusion in the analysis consisted of 19 articles. All articles included measures of NER, and 14 alsoincluded measures of PER. Because many of the articles includes measures of multiple response systems, overall there

were 29 measures of NER and 24 measures of PER across response systems. The pooled sample size consisted of 465

participants with MDD and 452 control participants. See Table 1 for a summary of selected characteristics of studies

included in the meta-analysis1.

The demographic characteristics of participants in the included studies appeared to be consistent with the known

epidemiology of MDD. The majority of the studies included more females than males in their samples, consistent with

the prevalence rate of depression being higher in females (Kessler, 2002). Seven studies only included female

participants, and one only included males. Most studies specified excluding participants with co-morbid psychosis,

bipolar disorder, or substance abuse. However, co-morbid anxiety diagnoses were typically included (only two studies

stated that they excluded for all anxiety disorders). Five studies specified including inpatient MDD samples, and 11

specified using outpatient samples. The majority of included studies did not report ethnicity or other participantdemographic information. Only one study (Tsai, Pole, Levenson, & Munoz, 2003) used a minority sample which

consisted of Spanish-speaking Latinas, and one study used a British sample in London ( Kaviani, Gray, Checkley,

Raven, Wilson, & Kumari, 2004).

2.7. Computation of effect sizes

We conducted the analyses using the Hedges and Olkin approach (1985) which weights each study by the inverse

of the variance, which is roughly proportional to the study's sample size. Effect sizes were computed using Cohen's

1 Studies excluded from the meta-analysis after the initial screening.

No control group:

Carney, Hong, Brim, Plesons, and Clayton (1983)

Greden, Price, Genero, Feinberg, and Levine (1984)

Rottenberg, Wilhelm, Gross, and Gotlib (2002)

Rottenberg, Salomon, Gross, and Gotlib (2005)

Schwartz, Fair, Mandel, Salt, Mieske, and Klerman (1976)

Schwartz, Fair, Salt, Mandel, and Klerman (1976)

No baseline or neutral measure:

Berenbaum and Oltmanns (1992)

Katsikitis and Pilowsky (1991)

Renneberg, Heyn, Gebhard, and Bachmann (2005)

Tremeau et al. (2005)

Not laboratory studies (naturalistic):

Peeters, Nicolson, and Berkhof (2003)

Peeters, Nicolson, Berkhof, Delespaul, and deVriews (2003)

Missing data necessary for computation of effect sizes:

Iacono, Lykken, Haroian, Peloquin, Valentine, and Tuason (1984)

Lapierre and Butter (1980)

Wexler, Levenson, Warrenburg, and Price (1994)Yecker, Borod, Brozgold, Martin, Alpert, and Welkowitz (1999).

681L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

7/16

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

8/16

d, a common measure of effect size (Cohen, 1988). Effect sizes were calculated as (M1M2)/SDp where M1 is the

control group mean, M2 is the MDD group mean, and SDp is the pooled standard deviation. This represents the

standardized mean difference between groups. Standardizing these means allowed us to account for scaling

differences between different types of measures and pool data across studies. The means used to compute the effect

sizes were the average self-report, behavioral, or physiological emotional reactivity scores. If the study did not

report emotional reactivity scores directly, these scores were derived by subtracting neutral or baseline conditionmean scores from positive or negative response mean scores. In this case, the standard deviation was first pooled

from the standard deviations of the positive and negative response mean scores and the neutral or baseline

conditions, and then this pooled standard deviation was used in the equation above to pool across groups in the

calculation of the effect sizes. All effect sizes were calculated using the Comprehensive Meta-analysis software

package (Biostat, 2005).

A variety of stimuli in the primary studies were used to elicit valenced emotional responses that have received

some support from previous research as being valid measures of emotional reactivity, including emotional films or

audio recordings describing an emotional situation (Rottenberg, Ray, & Gross, 2007), emotional pictures from the

International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2005), facial expressions of emotion from

the Facial Affective Booklet (FAB; Ekman, 1976, Ekman & Oster, 1979), standardized laboratory stressors such as a

loud noise or mental arithmetic tasks (Krantz, Manuck, & Wing, 1986), and the presentation of rewards (Henriques,Glowacki, & Davidson, 1994). Most of the behavioral and physiological studies also used self-report measures to

validate whether the appropriate emotion was elicited. In order to ensure that emotional reactivity, defined as

emotional reaction to a particular positively or negatively valenced stimulus, rather than a more general disposition

of mood was assessed, we defined PER and NER as a change from a baseline condition. Rest and response to a

neutral stimulus (e.g., a neutral film) were both considered acceptable baselines. We felt this liberal definition of

baseline was justified in light of disagreement concerning what constitutes an optimal baseline condition for

assessing the effects of emotional reactivity (for a discussion see, for example, Rottenberg et al., 2007). The more

liberal definition of baseline also allowed us to retain as many studies as possible in the meta-analysis. Nevertheless,

when both a resting baseline and a neutral baseline were reported in the same study, we used the neutral condition,

because we believe there are drawbacks associated with using the resting baselines (e.g., rest may not be a

representative state of the organism, rest instructions may introduce unwanted variability, etc. For details, see

Rottenberg et al., 2007).When the authors of the studies included in the meta-analysis used more than one type of emotional reactivity

measure for PER or NER those effect sizes were summarized by simply using the mean effect size for the omnibus

analyses. For the analyses within each domain, averaging was only done if there was more than one emotional

reactivity measure for PER or NER within a domain. Using the mean effect size is conservative, as it gives a lower

estimate compared to overall composite variables (Rosenthal & Rubin, 1986). An alternate method would be to

calculate the overall composite effect sizes. However, in order to make this computation, the inter-correlations between

the multiple dependent measures would be needed and, in most studies, they were not reported.

2.8. Planned analyses

Primary omnibus analyses examined NER and PER across emotion response systems. Since activity in differentemotion response systems are not always strongly inter-correlated (Lang, 1968; Mauss, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2004),

and may even dissociate (e.g., Lang, 1988), we conducted secondary analyses within each emotion response

domain (reported experience, behavior, and physiology) to examine the consistency of emotional reactivity across

domains.

The primary analyses employed a fixed effects model, which has high power and remains the predominant model in

meta-analyses of psychological research (Hunter & Schmidt, 2000). However, fixed effects models have been

criticized for inflating Type I error, especially if there is heterogeneity in the data (Hunter & Schmidt, 2000). Due to the

small number of studies available for this meta-analysis and the unknown size of the expected effects, we chose to use

the fixed effects model as the primary model. We also ran tests of heterogeneity of the effect sizes using Cochran's

heterogeneity statistic Q (Cochran, 1954). Since heterogeneity can potentially inflate Type I error in a fixed effects

approach, we planned to re-run the analyses using a random effects model, if analyses revealed significant

heterogeneity in the data.

683L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

9/16

3. Results

3.1. Omnibus analyses

We first conducted omnibus analyses of positive and negative emotional reactivity using the fixed effects model.

The analysis of positive emotional reactivity (PER) was significant (pb .0001) and revealed that PER was reduced inMDD compared to normal controls (see Fig. 1). The effect size for PER was d= .53, a medium-sized effect by

Cohen's (1988) conventions. Similarly, the omnibus analysis of negative emotional reactivity (NER) was also

significant, (pb .0001) and revealed that NER was reduced in MDD compared to normal controls (see Fig. 1). The

effect size for NER was d= .25, corresponding to a small effect size. When PER and NER effect sizes were compared

in a moderator analysis (with effect type PER versus NER coded as a moderator variable), a significant effect was

obtained (Q =7.21, pb .01), reflecting that the PER effect was significantly larger than the NER effect, indicating that

MDD individuals exhibited a more pronounced blunting of PER than of NER.

Fig. 1. PER and NER across all domains. The MDD group exhibits reduced PER and NER compared to controls ( pb

.0001). Error bars represent 95%confidence intervals.

684 L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

10/16

We conducted analyses of heterogeneity of both the PER and NER omnibus analyses to measure the variation

around the mean weighted effect sizes. Significant heterogeneity was present for both PER (Q =111.80, pb .0001) and

NER (Q =34.77, p = .01). Given the presence of heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect sizes, we ran the planned

follow-up random effects analysis for PER and NER. The random effects analyses, despite their reduced power,

revealed similar results for both PER (d= .59, p =.011) and NER (d= .26, p =.008), with virtually identical effect

sizes to those in the fixed effects analyses. Since the heterogeneity in omnibus analysis suggests the possible presenceof moderator variables, additional analysis of potential moderators is presented below.

3.2. PER and NER in individual response systems

3.2.1. PER

To examine the extent to which reduced PER generalized across different systems of emotional response, separate

meta-analyses were conducted on the self-report, behavioral, and physiological indicators of PER. For both self-report

and behavioral measures of PER, it was found that PER in MDD was reduced relative to controls. For self-report

measures of PER, the effect size was d= .703 (pb .0001), a large effect. This analysis included 10 studies with a

sample size of 263 MDD individuals and 249 controls. For behavioral measures of PER, the effect was medium-sized

(d=

.453, pb

.0001). The analysis of behavioral measures included 10 studies with 290 MDD individuals and 250controls. Only 4 studies (with a total sample of 122 MDD individuals and 89 controls) included physiological measures

of PER, and although the direction of effect was also towards a reduction of PER in MDD, none of these found a

significant effect. When data from these 4 studies was pooled the overall analysis was non-significant (p =.293), with a

very modest effect size for PER (d= .151).

3.2.2. NER

To examine the extent to which reduced NER generalized across different systems of emotional response,

separate meta-analyses were conducted for self-report, behavioral, and physiological indicators of NER. For self-

report measures of NER, the effect size was medium ( d= .359, pb .0001). This analysis included 11 studies with

a total sample size of 279 MDD individuals and 264 controls. For behavioral measures, the effect size was small

(d= .054, and was not statistically significant, p =.544). For the analysis of behavioral measures, there were 9

studies, with a sample of 290 MDD individuals and 249 Controls. Finally, there was a medium effect forphysiological measures of NER (d= .223, pb .05). For the physiological measures, there were 8 studies, with a

sample size of 196 MDD individuals and 220 controls. In sum, similar to results for PER, when each emotional

response system was examined separately individuals with MDD exhibited reduced NER compared to controls in

two of the three systems.

3.3. Heterogeneity and Moderator Analyses

Omnibus analyses presented earlier indicated that effect sizes for both PER and NER were heterogeneous. Given

that all three distinct response systems were analyzed together, this was not completely surprising. To help isolate the

sources of heterogeneity, we also ran tests of heterogeneity within each emotion response system. For NER, the effect

sizes in the physiological analyses had significant heterogeneity (Q =21.16, pb .01), self-report effect sizes hadmarginally significant heterogeneity (Q =17.19, p =.05) and behavioral (Q =8.67, p =.37) were not heterogeneous. For

PER, behavioral (Q =150.46, pb .0001) and self-report (Q =86.70, pb .0001) but not physiological analyses (Q =0.39,

p =.82) indicated significant heterogeneity. Thus, the only response system which exhibited heterogeneity with any

consistency was self-reported emotion, which may be due to the diverse measures included within this domain of

emotional responding. Heterogeneity can also indicate the presence of outliers in the data. The PER behavioral

measures demonstrated most notable degree of heterogeneity. From a visual inspection of the plot of the PER

behavioral effects sizes, it would appear that were two outliers present. Specifically, all of the effect sizes fell within the

narrow range of .22 to +.10 except for two outliers (+0.64 and 3.95).

The presence of moderator variables, which systematically influence the effect sizes, can also cause heterogeneity.

We originally intended to run additional moderator analyses designed to identify variables that might account for

systematic variation in PER and NER effect sizes (e.g., medications, depression severity, co-morbidity). Unfortunately,

these analyses were either impossible due to inadequate information from primary studies and/or were underpowered

685L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

11/16

(see Discussion below).2 The small subset of studies available for each response system likewise precluded adequately

powered analyses of potential moderator variables within each system.3

3.4. File drawer analyses

Finally, since our review considered only published sources, we conducted file-drawer analyses to assess thereliability of the omnibus effects in the face of additional unpublished null results ( Rosenthal, 1991). For the probability

for the omnibus analysis of PER to become non-significant (pN .05), there would have to be over 90 unpublished

studies with non-significant results hidden away in the file-drawer. Similarly, for the omnibus analysis of NER to

become non-significant, over 40 unpublished studies with non-significant results would be needed.

4. Discussion

MDD is well-established as a disorder of mood, but theories and prior narrative reviews have disagreed about how

MDD influences ongoing emotional reactivity. This meta-analysis represents the first quantitative review of the MDD

emotional reactivity literature. The major results indicate that MDD involves consistent reductions in both PER and

NER. These results have implications for each of the three major views of emotional reactivity in MDD. First, as NERwas found to be reduced rather than increased, the negative potentiation view was not supported. Second, the reduction

of PER in MDD, and the fact that the PER effect was larger than the NER effect both provided good support for the

positive attenuation view. Third, the ECI view appears to offer the most parsimonious overall account of these data

because (1) the pattern of decreased emotion reactivity in MDD was not restricted to PER, and (2) the ECI view

uniquely predicts reduced NER.

Lending additional credence to the ECI view, these reductions in PER and NER were robust in several respects.

First, both effects were highly statistically reliable. Second, file-drawer analyses indicated that the present results for

overall NER and PER would hold even in the face of a substantial number of unpublished null results. And third, the

reductions in PER and NER appeared to generalize across different systems of emotional response, and were not

restricted to a single response system.

These results also have more general implications for the study of how moods and emotions interact. Although

moods and emotions are highly familiar constructs that have generated extensive research, it is not yet clear how thesetwo kinds of affective processes are related. Intuitively, it makes sense that emotional reactions are stronger when they

are congruent with a preexisting mood, an idea reinforced by contemporary emotion theory. Yet there are surprisingly

few strong empirical demonstrations that moods actually facilitate emotional reactivity to mood-congruent stimuli. In

this respect, the analyses presented here appear to provide a notable exception to the idea of mood-facilitation.

Excessive negative mood in MDD should potentiate NER by the logic of mood-facilitation, yet this was clearly not the

case in the present data. One hypothesis to help make sense of this paradox is that moods may have non-linear effects

on emotional reactivity, with mood-facilitation holding for mild and moderate depressed mood states but not for severe

depressed mood states. Although this hypothesis waits further testing, the idea that milder depression potentiates NER

2 For example, we attempted to examine whether depression severity exerted a systematic effect on emotion reactivity in MDD; however, the

studies included in the meta-analysis inconsistently reported severity measures. For the measures that reported BDI scores for the MDD group,

we correlated these scores with the NER and PER effect sizes. No significant correlation was found for either NER ( r=.156, p =.647) or PER

(r= .452, p =.190); however, this may be due to the limited number of studies providing BDI data (11).3 Given that depression is defined diagnostically by tonic mood disturbances, we conducted additional exploratory analyses that examined the

extent to which PER and NER differences between studies in self-reported, behavioral, and physiological reactivity might be explained by tonic,

baseline differences in each corresponding system of measured response. In self report of affect at baseline, as expected, MDD individuals on

average reported less positive affect (d=0.865, pb .0001) and more negative affect (d=1.454, pb .0001) than controls. However, correlational

moderator analyses did not find a significant relationship between the magnitude of positive affect baseline differences and self-report indices of

PER (r=.26, p =.49). Likewise, no significant relationship was found between the magnitude of negative affect baseline differences and self-report

indices of NER (r=.48, p =.34). For behavioral measures, the groups did not differ at baseline in positive ( d=.005, p =.968) or negative (d= .154,

p = .188) behavioral indices. For physiological indices, MDD individuals exhibited higher activation at baseline compared to controls (d=.263,

pb .05). Too few studies were available to examine the association of baseline physiology with physiological indices of PER. However, the

magnitude of the difference in baseline activation was not correlated with physiological indices of NER ( r= .352, p =.439). Although the low

number of included studies limited the power of these analyses, there did not appear to be a strong relationship between tonic differences in responseand observed differences in PER and NER.

686 L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

12/16

is consistent with a number of analog studies of dysphoric samples that have obtained data consistent with this

prediction (Golin, Hartman, Klatt, Munz, & Wolfgang, 1977; Lewinsohn, Lobitz, & Wilson, 1973 ). Careful assessment

of emotional reactivity in samples that contain individuals with the full range depressed mood will be critical for testing

for non-linear effects, an analysis that may enrich an already active debate about whether depression is best conceived

as a continuum or a discrete category (e.g., Beach & Amir, 2003).

4.1. Limitations and future directions

While this study adds to our knowledge about emotions in MDD and has implications for the understanding of

normal mood variation, four important limitations should be noted. First, to estimate effect sizes for PER and NER, this

review prioritized the controlled measurement of emotion in laboratory settings. It is an open question as to whether

these laboratory findings generalize to naturalistic settings. The research database that examines emotion in everyday

life adults among with MDD is currently limited; thus studies that use emotion experience sampling techniques (e.g.,

Peeters, Berkhof, Delespaul, Rottenberg, & Nicolson, 2006) or informant ratings of emotion drawn from ecologically

important contexts (e.g., spousal relations) represent important directions for future work.

Second, there was significant heterogeneity in the omnibus analyses of NER and PER as well as consistent

heterogeneity in the self-report system when individual response systems were analyzed, but the proximal source(s) ofthis heterogeneity were difficult to isolate. Second, we were not able to identify moderators that might explain

systematic variation in PER and NER effect sizes across studies, either because the relevant information in the primary

studies was incomplete or absent and/or because the analyses of candidate moderators were underpowered. This point

merits emphasis.

For example, it is possible that the antidepressant medications commonly taken by individuals with MDD could

influence the magnitude of PER and NER (Tomarken, Shelton, & Hollon, 2007). The studies in this meta-analysis were

disparate in their practices with respect to medications. Very few studies used a non-medicated or an all-medicated

sample, and the all-medicated samples were often taking a variety of medications, which typically were not reported in

sufficient detail to analyze in any meaningful way.

Another possible moderator that could not be addressed by the present meta-analysis was co-morbid

psychopathology in the MDD individuals. Most studies did not exclude for anxiety or personality disorder co-

morbidity, and did not report emotional reactivity in pure MDD separately. In fact, only two studies excluded for alltypes of anxiety disorders in MDD individuals, which are commonly co-morbid with MDD (DSM-IV; APA, 2000). The

effect of co-morbid disorders on PER and NER in MDD is not well understood, but there are indications in the

literature that anxiety levels and forms of co-morbidity such as substance use (Zvolensky & Schmidt, 2003) may

influence the magnitude of observed effects on emotional reactivity in MDD. For example, one study (Kaviani et al.,

2004) found that within MDD individuals, anxiety levels as measured by self-report measures were associated with

increasedreactivity as measured by EMG for both positively and negatively valenced film clips. In sum, the presence

of normative co-morbidity in MDD samples precludes any strong claim that blunted emotional reactivity is specific to

MDD. To advance such a claim, it would be useful to have carefully conducted comparisons of emotional reactivity

between pure samples of MDD participants, co-morbid MDD participants and participants with other psychiatric

conditions.

Moreover, heterogeneity of MDD samples with respect to symptom severity, and demographic characteristics arealso potential factors that influences the magnitude of PER and NER. Samples of MDD individuals in this meta-

analysis were drawn from a variety of sources and included inpatients, outpatients, and untreated individuals recruited

from the general population. Preliminary moderator analyses designed to examine the relationship between depression

severity and emotion reactivity found no relationship (see footnote 1), but because of incomplete data, this analysis did

not provide a strong test. Other work has suggested that the severity of MDD may have an effect on emotion reactivity

(Rottenberg, Kasch et al., 2002). Finally, it is also possible that emotional reactivity in MDD varies as a function of

depression subtype (e.g., atypical versus melancholic MDD). Unfortunately, the majority of the studies did not specify

into which subtype individuals in their MDD samples fell. Finally, the sparse reporting of race, ethnicity, and

socioeconomic status, precluded analyses of these factors despite the fact that these demographic factors may be

important in modifying emotional reactivity (e.g., Gallo, Bogart, Vranceanu, & Matthews, 2005).

In light of these considerations, we strongly recommend that researchers be more conscientious in their reporting on

possible moderators of emotional reactivity in MDD, including medications, co-morbid anxiety, gender, demographic

687L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

13/16

variables, depression severity, depression subtypes. Importantly, despite the multiple factors which might influence

PER and NER, and the well known heterogeneity of depression, this meta-analysis found reliable effects for NER and

PER. In fact, the effect sizes for NER and PER appear to be comparable in magnitude to those found in other meta-

analyses in related domains (e.g., Matt, Vazquez, & Campbell, 1992; Mor & Winquist, 2002).

Finally, as noted earlier, a fourth limitation of this meta-analysis is that it did not include every response system that

is relevant to the emotion construct. Thus, one important avenue for future work will be to examine the generalizabilityof the findings presented here to other response systems. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis of a substantial literature

on endocrine responses to stress in MDD (which focused on the hormone cortisol) found reduced reactivity in MDD

(Burke, Davis, Otto, & Mohr, 2005), which is consistent with the ECI view. Evidence from neural systems involved in

emotional responding in MDD is not easily summarized in narrative form, but the possibility should be noted that

findings may be more mixed than our meta-analytic results. For example, Deldin, Keller, Gergen, and Miller (2000)

used ERP to measure encoding of emotional stimuli in individuals with MDD and controls and found that controls

showed enhanced P300 during encoding and reduced P300 during recognition of positive stimuli, which the authors

interpreted as a response bias for positive information. Using fMRI, a blunted response in the amygdala to facial

expressions of fear (relative to neutral) has been observed in both depressed adults (Drevets, 2001) and depressed

children (Thomas et al., 2001), which might be interpreted in terms of ECI. However, consistent with the negative

potentiation view, Siegle, Steinhauer, Thase, Stenger, and Carter (2002) found that MDD individuals exhibited asimilar initial amygdala response but greater sustained amygdala activity in response to negative words. In this same

study, and underlining the complexity of this domain, the MDD individuals exhibited decreased reactivity in

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), compared to controls for the same negative words. Relatedly, Canli, Sivers,

Thomason, Whitfield-Gabrieli, Gabrieli, and Gotlib (2004) found that MDD individuals had increased reactivity to

negative words in the inferior parietal lobule (IPL) but decreased reactivity in the superior temporal gyrus (STG) and

the cerebellum. The high complexity of these neuroimaging findings again underlines our caution in not assuming the

generalizability of these results to other systems of emotional response.

4.2. Conclusions

Clinical scientists have increasingly recognized the importance of emotion to understanding psychopathology

(Kring & Bachorowski, 1999; Rottenberg & Johnson, 2007). Given this wide interest, the field has been surprisinglyslow to undertake quantitative reviews of emotional reactivity in Axis-I disorders. This report, as the first quantitative

review of emotion reactivity in major depression, begins to address this gap by suggesting that changes in emotional

reactivity are a reliable correlate of MDD. In addition to augmenting the clinical description of MDD as a disorder of

emotion, these analyses have implications for interventions designed to treat and prevent MDD. For example, to the

extent that diminished emotional reactivity is a key affective deficit in MDD, it may be the case that individuals who

strongly exhibit this deficit will have a more pernicious course of disorder (e.g., Rottenberg, Wilhelm et al., 2002). This

logic would also support the development of psychologically-based and pharmacological treatment techniques to

bolster MDD patients' appropriate reactivity to both positive and negative emotional stimuli. In fact, given the

centrality of affective disturbance in MDD, developing an accurate, system-by-system account of how MDD alters

emotional reactivity, including testing hypothesized proximal mechanisms (e.g., individual differences in cognition or

biological functioning), is a sine qua non for developing more effective, targeted treatments for this disorder. Wesubmit this meta-analysis as a modest first step towards this goal.

References

*Albus, M., Muller-Spahn, F., Ackenheil, M., & Engel, R. R. (1987). Psychiatric patients and their response to experimental stress. Stress Medicine,

3, 233238.

*Allen, N. B., Trinder, J., & Brennan, C. (1999). Affective startle modulation in clinical depression: Preliminary findings. Biological Psychiatry, 46,

542550.

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Appelhans, B. M., & Luecken, L. J. (2006). Heart rate variability as an index of regulated emotional responding. Review of General Psychology, 10,

229240.

Studies included in the meta-analyses.

688 L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

14/16

Barrett, L. F. (2006). Valence is a basic building block of emotional life. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 3555.

Beach, S. R., & Amir, N. (2003). Is depression taxonic, dimensional, or both? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 228236.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: The Guilford Press.

Berenbaum, H., & Oltmanns, T. F. (1992). Emotional experience and expression in schizophrenia and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

101, 3744.

Biostat. (2005). Comprehensive meta-analysis [Computer software].Bradley, M. M., Cuthbert, B. N., & Lang, P. J. (1999). Affect and the startle reflex. In M. E. Dawson A. Schell & A. Boehmelt (Eds.), Startle

modification: implications for neuroscience, cognitive science and clinical science (pp. 242276). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy

and Experimental Psychiatry, 25, 4959.

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2000). Measuring emotion: Behavior, feeling, and physiology. In R. D. Lane & L. Nadel (Eds.), Cognitive

neuroscience of emotion (pp. 106128). New York: Oxford University Press.

Butler, E. A., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2006). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, emotion, and emotion regulation during social interaction.

Psychophysiology, 43, 612622.

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36, 129148.

Burke, H. M., Davis, M. C., Otto, C., & Mohr, D. C. (2005). Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. Psycho-

neuroendocrinology, 30, 846856.

Cacioppo, J. T., Martzke, J. S., Petty, R. E., & Tassinary, L. G. (1988). Specific forms of facial EMG response index emotions during an interview:

From Darwin to the continuous flow hypothesis of affect-laden information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54,

592

604.Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Losch, M. E., & Kim, H. S. (1986). Electromyographic activity over facial muscle regions can differentiate the valence

and intensity of affective reactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 260268.

Canli, T., Sivers, H., Thomason, M. E., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Gabrieli, J. D., & Gotlib, I. H. (2004). Brain activation to emotional words in depressed

vs. healthy subjects. NeuroReport, 15, 25852588.

Carney, R. M., Hong, B. A., Brim, J., Plesons, D., & Clayton, P. (1983). Facial electromyography and reactivity in depression. The Journal of

Nervous and Mental Disease, 171, 312313.

Carver, C. S. (2001). Affect and the functional bases of behavior: On the dimensional structure of affective experience. Personality and Social

Psychology Review, 5, 345356.

Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Mineka, S. (1994). Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

Special Issue: Personality and Psychopathology, 103, 103116.

Cochran, W. (1954). The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics, 10, 101129.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

*Dawson, M. E., Schell, A. M., & Catania, J. J. (1977). Autonomic correlates of depression and clinical improvement following electroconvulsive

shock therapy. Psychophysiology, 14, 569577.

Deldin, P. J., Keller, J., Gergen, J. A., & Miller, G. A. (2000). Right-posterior face processing anomaly in depression. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 109, 116121.

Depue, R. A., & Iacono, W. G. (1989). Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 457492.

*Dichter, G., Tomarken, A., Shelton, R., & Sutton, S. (2004). Early- and late-onset startle modulation in unipolar depression. Psychophysiology, 41,

433440.

Dolan, R. J. (2002). Emotion, cognition and behavior. Science, 298, 11911194.

Drevets, W. C. (2001). Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood

disorders. Current Directions in Neurobiology, 2001, 240249.

*Dunn, B. D., Dalgleish, T., Lawrence, A. D., Cusack, R., & Ogilvie, A. (2004). Categorical and dimensional reports of experienced affect to

emotion-inducing pictures in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 654660.

Ekman, P. (1976). Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 169200.

Ekman, P., Matsumoto, D., & Friesen, W. V. (2005). Facial expression in affective disorders. In P. Ekman & E. L. Rosenberg (Eds.), What the facereveals: basic and applied studies of spontaneous expression using the facial action coding system (FACS) (pp. 429440). (2nd edition) New York:

Oxford University Press.

Ekman, P., & Oster, H. (1979). Facial expressions of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 30, 527554.

*Forbes, E. E., Miller, A., Gohn, J., Fox, N., & Kovacs, M. (2005). Affect-modulated startle in adults with childhood onset depression: relations to

bipolar course and number of lifetime depressive episodes. Psychiatry Research, 134, 1125.

Fox, P. T., Parsons, L. M., & Lancaster, J. L. (1998). Beyond the single study: Function/location metanalysis in cognitive neuroimaging. Current

Opinion in Neurobiology, 8, 178187.

Gallo, L. C., Bogart, L. M., Vranceanu, A., & Matthews, K. A. (2005). Socioeconomic status, resources, psychological experiences, and emotional

responses: A test of the reserve capacity model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 386399.

*Gehricke, J. G., & Shapiro, D. (2000). Reduced facial expression and social context in major depression: Discrepancies between facial muscle

activity and self reported emotion. Psychiatry Research, 95, 157167.

Golin, S., Hartman, S. A., Klatt, E. N., Munz, K., & Wolfgang, G. L. (1977). Effects of self-esteem manipulation on arousal and reactions to sad

models in depressed and nondepressed college students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86, 435439.

Gray, J. R. (2004). Integration of emotion and cognitive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 46

48.

689L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

15/16

*Greden, J. F., Genero, N., Price, L., Feinberg, M., & Levine, S. (1986). Facial electromyography in depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43,

269274.

Greden, J. F., Price, L., Genero, N., Feinberg, M., & Levine, S. (1984). Facial EMG activity levels predict treatment outcome in depression.

Psychiatry Research, 13, 345352.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281291.

*Guinjoan, S. M., Bernabo, J. L., & Cardinali, D. P. (1995). Cardiovascular tests of autonomic function and sympathetic skin responses in patients

with major depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 59, 299

302.Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

*Henriques, J. B., & Davidson, R. J. (1991). Left frontal hypoactivation in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 535545.

Henriques, J. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2000). Decreased responsiveness to reward in depression. Cognition and Emotion, 14, 711724.

Henriques, J. B., Glowacki, J. M., & Davidson, R. J. (1994). Reward fails to alter response bias in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103,

460466.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2000). Fixed effects vs. random effects meta-analysis models: Implications for cumulative research knowledge.

International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 8, 275292.

Iacono, W. G.,Lykken,D. T., Haroian, K. P., Peloquin,L. J.,Valentine, R. H.,& Tuason, V. B. (1984). Electrodermal activity in euthymic patients with

affective disorders: One-year retest stability and the effects of stimulus intensity and significance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 304311.

Katsikitis, B. A., & Pilowsky, I. (1991). A controlled quantitative study of facial expression in Parkinson's disease and depression. Journal of

Nervous and Mental Disease, 179, 683688.

*Kaviani, H., Gray, J. A., Checkley, S. A., Raven, P. W., Wilson, G. D., & Kumari, V. (2004). Affective modulation of the startle response in

depression: Influence of the severity of depression, anhedonia, and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 83, 2131.

Keltner, D., & Gross, J. J. (1999). Functional accounts of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 575

599.Kessler, R. C. (2002). Epidemiology of depression. In I. H. Gotlib & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (pp. 2342). New York:

Guilford Press.

Krantz, D. S., Manuck, S. B., & Wing, R. R. (1986). Psychological stressors and task variables as elicitors of reactivity. In K. A. Matthews S. M.

Weiss T. Detre T. M. Dembroski B. Falkner S. B. Manuck & R. B. Williams (Eds.), Handbook of stress reactivity and cardiovascular disease

(pp. 85107). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Kring, A. M., & Bachorowski, J. A. (1999). Emotion and psychopathology. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 575600.

Lang, P. J. (1968). Fear reduction and fear behavior: Problems in treating a construct. In J. M. Shlien (Ed.), Research in Psychotherapy, Vol. 3

(pp. 90103). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lang, P. J. (1988). What are the data of emotion? In V. Hamilton G. H. Bower & N. H. Frijda (Eds.), Cognitive perspectives on emotion and

motivation (pp. 173191). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (2005). International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction

manual. Technical Report A-6. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

Lang, P. J., Greenwald, M. K., Bradley, M. M., & Hamm, A. O. (1993). Looking at pictures: affective, facial, visceral, and behavioral reactions.

Psychophysiology, 30, 261273.

Lang, P. J., Rice, D. G., & Sternbach, R. A. (1972). The psychophysiology of emotion. In N. S. Greenfield & R. A. Sternbach (Eds.), Handbook of

psychophysiology (pp. 623643). New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Lapierre, Y. D., & Butter, H. J. (1980). Agitated and retarded depression: A clinical psychophysiological evaluation. Neuropsychobiology, 6,

217223.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. London: Oxford University Press.

LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain: the mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Levenson, R. W. (1994). Human emotions: A functional view. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions

(pp. 123126). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Lobitz, W. C., & Wilson, S. (1973). Sensitivity of depressed individuals to aversive stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

81, 259263.

Matt, G. E., Vazquez, C., & Campbell, W. K. (1992). Mood-congruent recall of affectively toned stimuli: A meta-analytic review. Clinical

Psychology Review, 12, 227255.

Mauss, I. B., Levenson, R. W., Carter, L., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2005). The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior,and physiology. Emotion, 5, 175190.

Mauss, I. B., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Is there less to social anxiety than meets the eye? Emotion experience, expression, and bodily

responding. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 631662.

Melamed, S. (1987). Emotional reactivity and elevated blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 217225.

Mor, N., & Winquist, J. (2002). Self-focused attention and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 638662.

Murphy, F. C., Nimmo-Smith, I., & Lawrence, A. D. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of emotions: A meta-analysis. Cognitive, Affective and

Behavioral Neuroscience, 3, 207233.

Nesse, R. M. (2000). Is depression an adaptation? Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 1420.

Peeters, F., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., Rottenberg, J., & Nicolson, N. A. (2006). Diurnal mood variation in major depressive disorder. Emotion, 6,

383391.

Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., & Berkhof, J. (2003). Cortisol responses to daily events in major depressive disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65,

836841.

Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., & deVriews, M. (2003). Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 203

211.

690 L.M. Bylsma et al. / Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 676691

-

8/2/2019 A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Re Activity in Major Depressive Disorder_Bylsma_et_al_2008_cpr

16/16

*Persad, S. M., & Polivy, J. (1993). Differences between depressed and nondepressed individuals in the recognition of and response to facial

emotional cues. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 358368.

Phan, K. L., Wager, T., Taylor, S. F., & Liberzon, I. (2002). Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: A meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in

PET and fMRI. NeuroImage, 16, 331348.

Renneberg, B., Heyn, K., Gebhard, R., & Bachmann, S. (2005). Facial expression of emotions in borderline personality disorder and depression.

Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 36, 183196.

Ritz, T., Thons, M., Fahrenkrug, S., & Dahme, B. (2005). Airways, respiration, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia during picture viewing. Psycho-physiology, 42, 568578.

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology, 2, 247270.

Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1986). Meta-analytic procedures for combining studies with multiple effects sizes. Psychological Bulletin, 99,

400406.

Rottenberg, J. (2005). Mood and emotion in major depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 167170.

Rottenberg, J. (2007). Major depressive disorder: Emerging evidence for emotion context insensitivity. In J. Rottenberg & S. L. Johnson (Eds.),

Emotion and psychopathology: Bridging affective and clinical science. Washington DC: American Psychological Society.

Rottenberg, J., & Gross, J. J. (2003). When emotion goes wrong: realizing the promise of affective science. Clinical Psychology: Science and

Practice, 10, 227232.

*Rottenberg, J., Gross, J. J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2005). Emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114,

627639.

Rottenberg, J. & Johnson, S. L. (Eds.). (2007). Emotion and psychopathology: Bridging affective and clinical science. Washington, D.C.: APA

Books.*Rottenberg, J., Kasch, K. L., Gross, J. J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2002). Sadness and amusement reactivity differentially predict concurrent and prospective

functioning in major depressive disorder. Emotion, 2, 135146.

Rottenberg, J., Ray, R. D., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion elicitation using films. In J. A. Coan & J. J. B. Allen (Eds.), The handbook of emotion

elicitation and assessment. London: Oxford University Press.

Rottenberg, J., Salomon, K., Gross, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2005). Vagal withdrawal to a sad film predicts subsequent recovery from depression. Psy-

chophysiology, 42, 277281.

Rottenberg, J., Wilhelm, F. H., Gross, J. J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2002). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia as a predictor of outcome in major depressive

disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71, 265272.

*Rottenberg, J., Wilhelm, F. H., Gross, J. J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2003). Vagal rebound during resolution of tearful crying among depressed and

nondepressed individuals. Psychophysiology, 40, 16.

Scher, C. D., Ingram, R. F., & Segal, Z. V. (2005). Cognitive reactivity and vulnerability: Empirical evaluation of construct activation and cognitive

diatheses in unipolar depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 487510.

Schwartz, G. E., Fair, P. L., Mandel, M. R., Salt, P., Mieske, M., & Klerman, G. L. (1976). Facial electromyography in the assessment of improvement

in depression. Psychosomatic Medicine, 40, 355360.

Schwartz, G. E., Fair, P. L., Salt, P., Mandel, M. R., & Klerman, G. L. (1976). Facial expression and imagery in depression: An electromyographic

study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 337347.

Siegle, G. J., Steinhauer, S. R., Thase, M. E., Stenger, V. A., & Carter, C. S. (2002). Can't shake that feeling: fMRI assessment of sustained amygdala

activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biological Psychiatry, 51, 693707.

*Sigmon, S., & Nelson-Gray, R. (1992). Sensitivity to aversive events in depression: Antecedent, concomitant, or consequent? Journal of

Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14, 225246.

*Sloan, D. M., Strauss, M. E., Quirk, S. W., & Sajatovic, M. (1997). Subjective and expressive emotional responses in depression. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 46, 135141.

*Sloan, D. M., Strauss, M. E., & Wisner, K. L. (2001). Diminished response to pleasant stimuli by depressed women. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 110, 488493.

Thomas, K. M., Dahl, R. E., Ryan, N. D., Neal, D., Birmaher, B., Eccard, C. H., et al. (2001). Amygdala response to faces in anxious and depressed

children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 10571063.

Tomarken, A. J., Shelton, R. C., & Hollon, S. D. (2007). Affective science as a framework for understanding the mechanisms and effects ofantidepressant medications. In J. Rottenberg & S. L. Johnson (Eds.), Emotion and psychopathology: Bridging affective and clinical science.

Washington DC: American Psychological Society.

Tremeau, F., Malaspina, D., Duval, F., Correa, H., Hager-Budny, M., Coin-Barious, L., et al. (2005). Facial expressiveness in patients with

schizophrenia compared to depressed patients and nonpatient comparison subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 92101.

*Tsai, J. L., Pole, N., Levenson, R. W., & Munoz, R. F. (2003). The effects of depression on the emotional responses of Spanish speaking Latinas.

Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 4963.

Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: The Guilford Press.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 10631070.

Wexler, B. E., Levenson, L., Warrenburg, S., & Price, L. (1994). Decreased perceptual sensitivity to emotion-evoking stimuli in depression.

Psychiatry Research, 51, 127138.