A Late Pleistocene Archaeological Site in SW Kentucky: The Phil

Transcript of A Late Pleistocene Archaeological Site in SW Kentucky: The Phil

Paper presented at the Developing International Geoarchaeology Conference, Knoxville, Tennessee, September 20-24, 2011

A Late Pleistocene Archaeological Site in SW Kentucky: The Phil Stratton Site

byRichard Michael Gramly, American Society for Amateur Archaeology

Although claims have been made for the presence of human beings in the New World prior to the 14th millennium before present, actual sites yielding sub- stantial assemblages of artifacts within unequivocal contexts are rare. This fact is hardly surprising since human pop- lations may have been small, and the search for their vestiges is in the hands of very few researchers. Too, this search has been side-tracked by the theory – long established among North American archaeologists – that Clovis (Llano) was the initial or colonizing archaeological culture of

the New World. A lack of success in discovering Pleistocene archaeological sites in the New World also stems from researchers’ dis-inclination to take cues from Old World archaeological records when building their predictive models of where ancient sites might be found.

A common type of archaeological site in the Old World during the Late Pleistocene is encampments at river fords or crossings that have been preserved under alluvium or glacial loess. Presumably residence near fords was preferred as mammals could be ambushed there (for

Figure 1. Cumberland point restored from four fragments, Phil Stratton site. Length - 4.20 inches (110 mm)..

example, see Soffer 1985: 234-248 for a discussion Upper Palaeolithic mammoth hunters along river banks of the Central Russian Plain), fish could be taken, and human communication was simplified. By inspecting modern river fords, a researcher has excellent expectations of finding Late Pleistocene as well as more recent archaeological sites; the presence of older (Middle, Early) Pleistocene sites at today’s river crossings is more problematic as river conditions may have changed and protecting sediments may have disappeared over long periods.

Another factor that complicates a search for river fords with traces of Pleistocene human habitation is the location of the ecotone or contact between different vegetational zones. Studies of modern-day hunters in Africa and elsewhere have shown that ecotones are favorable places for hunters and gatherers to live, as the resources of two environments may be exploited equally. River crossings in the neighborhood of a major ecotone, it is easy to believe, would have been preferred places to live. However, during the Late Pleistocene when regional environments changed rapidly, ecotones might have shifted significantly even within an human lifespan. The choicest places for human residence would have moved in step with environmental trends. The exact timing of such change is difficult to know.

Application of insights that Old World prehistorians have gained about Pleistocene site locations has been slow in coming to the New World. The quest for the most ancient habitation sites in the New World has not benefitted from a coherent strategy and predictive modeling. Instead, from the beginning North American prehistorians have relied heavily upon amateurs to alert them to promising localities (see, for example, David Meltzer’s account of the Folsom site discovery by cowboy George McJunkin). At best, this approach has been “hit-or-miss.”

A notable exception to the usual opportunistic searching for Late Pleistocene human vestiges is work by Darrin Lowery and his colleagues in the Delmarva Peninsula (Lowery 2009). There, on the margin of Chesapeake Bay, which harbors the drowned course of the lower Susquehanna River, archaeologists, geologists and soil scientists have tested sites older than the 14th millennium before present. Recognizing that loess is the key to preserving an archaeological record, they have discovered numerous encampments shallowly buried by wind-blown sediments. These sediments even show frost-wedging and polygonal jointing (D. Lowery, personal communication). The Delmarva Peninsula loess likely originated as fine-grain sediments that had been transported by the ancient Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers when they were swollen by meltwater from the Late Pleistocene (Wisconsin) continental glacier.

Phil Stratton Site ( N36 deg 41.020 min W86 deg 56.200 min) Retrospect. Better familiarity with inland site locations of the Old World during the Late Palaeolithic and an understanding why these same sites entered

the archaeological record might have resulted in earlier discovery of the Late Pleistocene Phil Stratton site, Logan County, SW Kentucky. This, large encampment, however, remained unknown, even to collectors, until 1997, when it was exposed during construction of a greenhouse. A knowledgeable, reconnoitering archaeologist might have anticipated the existence of the Phil Stratton site for the following reasons:

First, the prehistoric site overlooks and is downwind of a ford across the Red River (Figure 2). Animals approaching

Figure 2. The Phil Stratton site (A), the Old Stratton Farm site (B), and isolated find-spots of Cumberland points (marked by X) in relation to crossing places of the Red River (arrows).

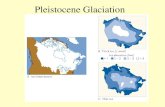

from several different directions could have crossed the river at this place – all the while in plain view of hunters. In this region the Red River is fast-flowing and difficult to negotiate because of limestone cliffs that border it. Good crossing places are few. Second, a major ecotone or contact zone between a spruce/fir-dominant forest and one dominated by hardwoods appears to have existed 14-15,000 years ago at the border between Kentucky and Tennessee in the neighborhood of the Phil Stratton site. It had reached as far south as Birmingham, Alabama 18,000 years ago during the height of the Wisconsin glaciation; just five thousand years afterward it had retreated as far north as New York state and New England (Jacobsen and Grimm 1988). Groups of Late Pleistocene hunters exploiting rich congeries of animals at the ecotone would have followed its movement ever northward as the Wisconsin glacier waned. They could not have passed through the Red River valley without taking notice of the advantages offered by the Phil Stratton site location. Third, but no less important, the Late Pleistocene Peorian loess blanketed southwestern Kentucky, including the Phil Stratton site (see Figure 3). It was laid down by prevailing winds out of the west that picked up silt across the Mississippi River valley. Shallowly buried by this loess and within their original context of deposition were flaked stone tools of the Cumberland Archaeological Tradition. Subsequently, these artifacts were dated absolutely to 14-15,000 years before present. The combination of the above three factors – geographic proximity to a

ford or river crossing, presence of a major ecotone, and preservation by burial under loess – account for the existence of the Phil Stratton site.

Figure 3. The geographical extent of the Peorian and Bignell loess of Late Pleistocene (Wisconsin) age. After Muhs et al. 2005: Figure 1. Note location of Phil Stratton site.

Position within the Loess and Absolute Age of the Ancient Occupation. At the Phil Stratton site only a narrow strip of Peorian loess with Palaeo-American artifacts survived cultivation, building of a green- house, road-work, and uprooting of trees. Many artifacts were displaced by construction activities during 1997, which led to the site’s discovery.

Also, part of the encampment occupying a steep, natural embankment sloping towards the Red River suffered erosion and re-deposition – thus reducing its value to archaeology. Fortunately, enough of the site escaped severe disturbances to enable detection of an ancient occupation “floor.” It lay 25-35 cm below the top of the loess and was marked by a concentration of large flaked

stone artifacts and rock manuports (see Figure 4). An artifact-bearing zone extended 10-15 cm below this floor as well as upward towards the surface. It was obvious to us excavators that natural bio-turbation during

the many millenia of shallow burial could have accounted for such vertical dispersal of artifacts – mostly small, light-weight tools and debitage.

Two well-preserved units nearly 40 meters apart and at opposite ends of the site (see Figure 5) were sampled for dating by optically

Figure 5. Extent of archaeological excavations (1999-2011) at the Phil Stratton site showing two locations where samples were collected for dating by optically stimulated luminescence (OSL).

Figure 4. Excavation of well-preserved unit S2E5 at the Phil Stratton site. A flaked stone adze resting at 35 cm below the surface of the loess is being photographed by R. M. Gramly while Phil Stratton, discoverer of the site, is preparing to resume excavating. November, 2005.

stimulated luminescence (OSL). Both units had relatively intact occupation floors within the loess (25 cm and 30 cm below surface) bracketed by a well-defined zone of vertically dispersed artifacts. The

unit lying within the western part of the site grid was sampled by J. Gomez of the Luminescence Dating Research Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago (see Figure 6); while, the unit in grid east was sampled by fieldcrew (see Figure 7). The deeper portions of the loess within both the east and west sampling units yielded regular successions of OSL dates, beginning with the onset

of the Wisconsin glacial epoch approximately 30,000 years ago. The series of OSL dates from 100-55 cm below surface (Table 1, view

below) allowed smooth dating curves to be graphed. Sediments in both units above 55 cm below surface, however, appear to have been affected by bio-turbation, as OSL determinations varied widely and were less old than would be expected.

Both dating curves were estimated to terminate at 12,800 years before present, which is the measured calendar age of the Brady soil in the American Great Plains. Loess deposition had ceased in the Mid-West by that time (Steve Holen, personal communication and Gramly 2009: 15). Likewise, at the Phil Stratton site

Figure 6. J. Gomez of the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Luminescence Dating Research Laboratory collects loess samples in the west wall of unit S3E5. June, 2006.

Figure 7. Column of soil sample locations for OSL dating at grid point S5.2 E42.4 – within Peorian loess of Wisconsin age.

accumulation of loess and the beginning of soil development are assumed to have occurred then.. Graphical solutions for the age of the Cumberland “floor” within sampling units at the eastern and western extremities of the Phil Stratton site – confirmed by computer-generated plots of OSL determinations – fell within the 15th millennium before present or a full 1,000 years older than the accepted age range for Clovis (Waters and Stafford 2007).Such a finding is in harmony with the antiquity of Cumberland artifacts in southern Tennessee and northern Alabama, as suggested by applications of the relative dating technique known as Infrared Laser Spectroscopy (ILS). It is argued that the beginnings of the Cumberland Tradition within the greater Tennessee River valley of northern Alabama and adjacent Tennessee may date to the 16th or 17th millennium before present (Dave Walley personal communication; see also McNutt et al. 2010). Such an age is in keeping with our idea of a northward-moving ecotone that offered attractive opportunities for early hunters of the New World.

An Artifact Assemblage of the 15th Millennium Before Present. To judge by the paucity of Archaic and Woodland artifacts recovered in our excavations, the Phil Stratton site was attractive as a residence only to Palaeo-American groups. Fewer than 30 Neo-Indianprojectile points were discovered scattered about 770 square meters of excavated deposits. Several of these points lay within humus near surface; evidently they had remained in those positions for thousands of years.

Within the upper third of the loess, artifacts of the Cumberland Tradition predominated. Judging by the patina on chert debitage and flaked tools, virtually every specimen can be relegated to the Palaeo-American era. Across disturbed sectors of the site, heavy machinery had damaged many artifacts, chipping away patina and revealing a darker-colored interior.

A total of 1,799 flaked stone tools, 27 hammerstones and abraders, and 23,330 debitage items are associable with the main occupation dated to the 15th millennium before present. This large assemblage – the most extensive on record for any New World archaeological site of the pre-Clovis era – is proof that this place along the Red River was utilized intensively. The nearly uniform carpet of stone debris covering the site, without any sharply demarcated concentrations, suggests protracted occupation – perhaps throughout the year. Also, the wide variety of flaked tools (see Table 2 , view below and Figure 8) indicates that it was more than just a temporary hunters’ camp. A heavy representation of the tool class, “cutters,” as well as a relative scarcity of endscrapers and

projectile points within so large an assemblage supports the notion that plants may have been processed – if not for food, then perhaps for manufacturing domestic articles such as baskets, burden straps, and coverings. In support of this idea we observed that several tools and pieces of debitage exhibited silica phytolith sheen.

Prismatic blades and bladelets that appear to have been generated by direct percussion from large, conical blade cores (see Figure 9, view below) constitute an important part of the Phil Stratton assemblage. Utilized prismatic blades and bladelets, in fact, outnumber simple utilized flakes. Most prismatic blades were used in unmodified form for cutting. A few

specimens were backed for hafting or holding in the hand, and a small

Figure 8. Selected Cumberland flaked stone tools, Phil Stratton site.

number were transformed into gravers and denticulates. Larger prismatic blades were selected for production of small fluted projectile points. For these points only the dorsal surface was fluted; while, the nearly flat flake release surface remained unfluted.

In comparison to Upper Palaeolithic industries of the Old World that are dominated by prismatic blades and tools based upon them, the industry at the Phil Stratton site seems impoverished and opportunistic. This finding would be expected if prismatic blade production were

autochthonous, that is to say, it had arisen independently in the New World. The stimulus for the development of a prismatic blade industry may lie with the genesis of fluted projectile points themselves. How and why these unique forms came into being (Gramly 2009) is a topic that merits fuller treatment elsewhere.

The Value of the Phil Stratton Site to Predictive Modelling. The simple structure of the Phil Stratton site and the essential stylistic homogeneity of its stone tool assemblage argue for a single, but protracted, episode of occupation by Palaeo-Americans. It is reasonable to believe that from this home base hunters and gatherers ranged over a broad region, up and down the Red River and its tributaries. One would not expect to discover other large, contemporary archaeological sites within the vicinity of Phil Stratton’s. Re-entry of the Red River valley by Cumberland point-using Palaeo-Americans when animal and plant resources had regenerated, however, seems likely. Such behavior has been observed in both modern hunting populations (Binford 1983)and the archaeological record of Palaeo-Americans in northeastern North America (Gramly 2005: 25-46).

Figure 9. Prismatic blade core, Phil Stratton site.

It follows that the validity of our hypothesis why Late Pleistocene hunters chose to encamp upon the Phil Stratton site can be tested by prospecting for other sites of its age at similar locations within the immediate neighborhood. In 2005, after close examination of a contour map, the existence of a second Cumberland site along the Red River was predicted and then confirmed. It lay upon high ground above a ford only three kilometers upstream of Phil Stratton’s. Part of this new site, which has been named Old Stratton Farm, we were pleased to observe, still remained under a protective blanket of glacial loess.

In my opinion the utility of a “riverine model” – wherein a site is preserved by loess at a ford that is not far from a major ecotone – was confirmed by the discovery of the Old Stratton Farm site. Only wider application of this model, however, will ensure that its value is recognized and endures. Richard Michael Gramly North Andover, Massachusetts September 2011

Acknowledgments Between 2000 and 2010, for a total of 25 weeks in the field, 55 volunteers contributed labor and expenses to the Phil Stratton site excavation. T. Beutell, S. Vaughn, and D. Walley made substantial cash contributions towards OSL dating and preparation of this and other manuscripts. No assistance from any governmental or public agency for this archaeological project was sought.

Table 1. OSL age determinations of loess samples for grid eastern and western excavation units, Phil Stratton site. Analyses by Luminescence Dating Research Laboratory, University of Illinois, Chicago.

Western Unit (2-m square S2E5 and west wall of unit S3E5) 1. 90 cm below surface...............29,980 +/- 2,320 years BP 2. 75 cm below surface...............16,720 +/- 1,300 years BP 3. 65 cm below surface...............18,320 +/- 1,380 years BP 4. 55 cm below surface...............17,020 +/- 1,210 years BP ********** 5. 45 cm below surface...............8,090 +/- 590 years BP 6. 40 cm below surface...............3,500 +/- 320 years BP 7. 30 cm below surface...............1,150 +/- 100 years BP 8. 30 cm below surface...............950 +/- 90 years BP

Eastern Unit (at grid point S5.2 E42.4) 1. 100 cm below surface............31,890 +/- 2,260 years BP 2. 90 cm below surface..............26,580 +/- 1,870 years BP 3. 80 cm below surface..............23,480 +/- 1,670 years BP 4. 70 cm below surface..............21,400 +/- 1,530 years BP 5. 60 cm below surface..............17,170 +/- 1,230 years BP ********** 6. 50 cm below surface..............11,210 +/- 810 years BP 7. 40 cm below surface..............6,175 +/- 485 years BP 8. 35 cm below surface..............4,880 +/- 350 years BP

Table 2. Breakdown of Cumberland stone tools and debitage at the Phil Stratton site.

TOOLS (whole counts)I. Rough stone A. Hones or whetstones = 8 B. Hammerstones = 19II. Flaked Stone A. Cutters 1. Utilized prismatic blades = 499 2. Utilized flakes = 276 3. Beaks = 394

4. Gravers = 137 5. Denticulates = 76 6. Burins = 14 TOTAL = 1,396 weighing 19,346.8 grams B. Scrapers 1. Hollow scrapers = 25 2. Simple sidescrapers = 24 3. Endscrapers = 10 4. Tchi-thos (boulder chip scrapers) = 9 5. Irregular scrapers = 6 6. Rabots = 2 7. Scrapers in combination with other tools a. Sidescraper + graver = 6 b. Sidescraper + endscraper = 5 c. Sidescraper + denticulate = 1 d. Sidescraper + beak = 1 e. Sidescraper + beak + denticulate = 1 f. Sidescraper + graver + hollow scraper = 1 TOTAL = 91 weighing 4,664.3 grams C. Bifaces 1. Cumberland points and preforms = 14 2. Square-based knives = 8 3. Stemmed flake-knives = 6 4. Adzes/celts = 5 5. Bifaces and biface fragments of indeterminate type = 29 TOTAL = 62 weighing 2,517.6 grams D. Choppers = 7 weighing 2,473.3 grams E. Miscellany 1. Awls = 1 weighing 1.2 grams 2. Pieces esquillees = 1 weighing 20.7 grams F. Tool fragments = 241 weighing 1,174.8 grams

DEBITAGE (in descending, estimated order of frequency) A. Flake fragments B. Biface reduction flakes C. Angular waste flakes D. Cortex removal flakes E. Pot-lid (thermally damaged) flakes F. Uniface resharpening flakes G. Channel flakes (N = 46 fragments, classed with utilized flakes) H. Exhausted and damaged cores I. Core rejuventation flakes TOTAL = 23,330 weighing 38,003.3 grams

References Cited

Binford, Lewis R. 1983 In Pursuit of the Past: Decoding the Archaeological Record. Thames and Hudson. New York.Gramly, Richard Michael 2005 The Upper/Lower Wheeler Dam sites: Clovis in the Upper Magalloway River valley, NW Maine. The Amateur Archaeologist 11(1): 25-46. 2009 Origin and Evolution of the Cumberland Palaeo-American Tradition. Persimmon Press. North Andover, Massachusetts.

Jacobsen, George L. And Eric C. Grimm 1988 Synchrony of rapid change in late-glacial vegetation south of the Laurentide ice sheet. In Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Paleo-Ecology and Archeology of the Eastern Great Lakes Region, edited by Richard S. Laub, Norton G. Miller and David W. Steadman, pp. 31-38. Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences 33. Buffalo, New York.

Lowery, Darrin L., Michael A. O’Neal, John S. Wah, Daniel P. Wagner and Dennis J. Stanford 2010 Late Pleistocene and upland stratigraphy of the western Delmarva Peninsula, USA. Quaternary Science Reviews, Issues 11-12: 1472-1481.

McNutt, Charles H., James F. Cherry and David H. Walley 2010 A Double-Blind Test of the Walley IR Raman Laser Technique for Relative Dating of Lithics. Manuscript on file, website of Museum of Native American History. Bentonville, Arkansas.

Meltzer, David J. 2006 Folsom: New Archaeological Investigations of a Classic Paleoindian Bison Kill. University of California Press. Berkeley.

Muhs, D. R., E. A. Bettis, III, J. Been and J. P. McGeehin 2005 Impact of climate and parent material on chemical weathering in loess-derived soils of the Mississippi River Valley. Soil Science Society of America Journal 65(6).

Soffer, Olga 1985 The Upper Paleolithic of the Central Russian Plain. Academic Press. New York.

Waters, Michael R. and Thomas W. Stafford, Jr. 2007 Redefining the age of Clovis: Implications for the peopling of the Americas. Science 315: 1122-1126.