A Father, a Daughter and a Procurator: Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of...

-

Upload

kate-cooper -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of A Father, a Daughter and a Procurator: Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of...

Gender & History ISSN 0953-5233Kate Cooper,‘A Father, a Daughter and a Procurator: Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage’Gender & History, Vol.23 No.3 November 2011, pp. 685–702.

A Father, a Daughter and a Procurator:Authority and Resistance in the PrisonMemoir of Perpetua of Carthage

Kate Cooper

Sometime in the winter or early spring of the year 203, a group of catechumens,neophyte Christians undertaking instruction for baptism, were arrested in Africa Pro-consularis. An uncertain tradition records that they came from the town of ThuburboMinus, a Roman colony established in the fertile grain lands along the river Bagradaaround forty-five kilometres to the west of the Roman governor’s capital at Carthage.Once the Christian group had been apprehended – perhaps interrupted during a prayermeeting or rounded up after being identified by a hostile informer – they were arrestedand taken to Carthage for questioning by the procurator, the emperor’s personal repre-sentative in the province. Eventually, they would be executed as criminals: condemnedto be attacked by wild animals during special gladiatorial games held in the amphi-theatre at Carthage, to celebrate the fourteenth birthday of Geta, the younger son ofthe reigning emperor Septimius Severus.1

In many ways, the story of Perpetua and her companions is one of a thousandstories that could be told about individuals and families in the Roman provinces whofell foul of the imperial authorities. What marks out this North African group fromother early Christian martyrs is not the fact that they were arrested, or even that theywere consigned to such a spectacular execution. Rather, it is the curious fact that theirstory – at least part of it – has come down to us in their own words. Two members of thegroup, a young mother called Perpetua and her spiritual brother Saturus, are believedto have written memoirs during their imprisonment. The narratives were preserved bythe Christian community at Carthage where they died, as a precious testimony of theircommitment to the faith.

Whether these texts were in fact written by the martyrs themselves has not beendefinitively resolved, and need not concern us here.2 Our focus in the present discussionis in the vision of household and empire evoked by the first-person voice of thenarrator ‘Perpetua’. This is a question of equal interest, mutatis mutandis, whetherPerpetua’s prison memoir was in fact written by the historical person Perpetua orwhether it represents a roughly contemporary writer’s attempt to imagine the thoughtsand experiences of such a person. In either case, the narrative invites its reader orhearer to share the thought-world of a narrator, Perpetua, who has to be distinguished

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

686 Gender & History

from the historical author even if the text was indeed written by Perpetua herself.3 Itis Perpetua the narrator who will serve as the object of our attention in the presentarticle. This said, our attention to how her concerns and circumstances are evoked inthe text will aim to address historical questions – what light close attention to thesecircumstances and concerns can shed on Roman social relations – rather than strictlyliterary concerns.

Nonetheless, there is a literary problem that must be addressed, at least briefly.The narratives of Perpetua and Saturus are transmitted in the medieval manuscriptswithin a ‘frame story’ penned by an ancient editor who explains their relationship toone another and offers what purports to be a description of their deaths, meaning thatthere are at least three, and possibly four, discrete voices at work in the narrative.4

It is important for our argument to recognise that the ancient editor who composedthe connecting narrative often interposed his or her reading, and was not necessarilywriting at the same time.

Again, this is a problem we have no need to resolve. But we will see below thatthe uncertain relationship between the prison diaries and the work of the ancient editoris potentially of importance, because the ancient editor occasionally gives evidenceof discomfort with some elements of the narratives of Perpetua and Saturus.5 Thereis reason to think that Perpetua was a more disturbing and subversive figure than theancient editor was happy to admit.

It has long been a scholarly convention to imagine that Perpetua of Carthagebelonged to a prominent citizen family. The interpretative tradition on this point goesback to the ancient editor, who refers to her as honeste nata, liberaliter instructa,matronaliter nupta – ‘well-born, well-educated, and honourably married’.6 But as weshall see below, a number of points in Perpetua’s own text undermine the editor’sassignment to her of the high-born status characteristic of ancient heroines. We mustconsider the possibility that the Perpetua of the prison memoir – whether heroine orhistorical woman – was none of the things claimed by the ancient editor. This hypothesisof a Perpetua drawn from the humbler classes will have remarkable consequences forour reading of her memoir as a document of the process of social control in the Romanprovinces.

Prisoners of conscience in Roman Carthage: religion, class and the socialmeaning of resistance to authority

Whether they were Christian or not, individuals and families depended on a networkof friends and family to vouch for them if they came into contact with the authorities.Public authority in the Roman Empire was articulated through social relationships andpersonal loyalties, and these relationships and loyalties could be mobilised in both atop-down and a bottom-up direction. Whether living in cities or smaller communities,Roman families had to be wary in case some activity or characteristic singled them outas suspect in the eyes of the local big men. Equally, other neighbours and associatesmight pass on gossip about those who were seen not to have shown enough enthusiasmfor the government and its policies.7 Sometimes this atmosphere of intimidation wouldbe the result of simple personal dislike, while in other cases there was real concernabout subversive religious or political views.

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 687

It goes without saying that Christian families were in a particularly difficultposition, because it was widely known that their religion disapproved of their takingoaths or making sacrifices to honour the emperor and the Roman gods. These acts ofloyalty were considered indispensable by the civic authorities, and those who wereunwilling to compromise their principles had to keep a very low profile indeed. At thesame time, the distinctive viewpoint of the prison diaries reveals itself forcefully in theirstrong emphasis on the dreams and visions that the catechumens experienced duringtheir time in custody. It is clear that the martyrs-in-waiting understood these dreamsand visions as messages from heaven through which they could seek to understandthe true meaning of what they were about to endure. This scheme of hidden meaningjustified their acts of resistance as signs of their loyalty to an otherworldly powermore deserving of loyalty than the Roman governor or emperor. Visionary literaturesuch as theirs represented a potentially explosive element in the imaginative landscapeof the later empire because of its potential to justify a refusal to bow to establishedauthority.8

We can approach the problem of how Roman households were woven into the‘veil of power’ of the Roman cities and provinces – to use Richard Gordon’s evocativephrase – from two angles.9 Looking from the top down, one can consider the strategiesplotted by emperors and proconsuls in order to attain hegemony over provincial pop-ulations. But one of the most productive strands of research in recent years has beento focus on how the elites of provincial cities took it upon themselves to maintain thenetworks of allegiance and stake-holding on which an empire depended (see GillianRamsey in this volume). Through thousands of private offerings to the gods and to thedeified emperors, individuals, families and cities both competed and collaborated inthe attempt to cultivate honour and favour.

In a landmark study of 1984, S. R. F. Price showed how this would have worked forthe imperial cult, in the well-documented cities of later Roman Asia Minor, arguing that‘the cult became one of the major contexts in which the competitive spirit of the localelites was worked out’10 Taking together actions that to a modern sensibility might seemto be ‘religious’ or ‘cultural’ and repercussions that might be understood as ‘political’or ‘economic’, Price offered a communicative model of cult and performance thataccounted for competition for advancement and standing among individuals in cities,and among cities in a province.11 We will see below that James Rives has identified acomparable two-way system of exchange where the cities of Roman North Africa areconcerned.

Identifying the self-interest of provincial elites as a driving force in the web ofritual connecting provincial cities to the imperial centre means that we cannot readthe acts of resistance of early Christian martyrs (and others) as simple acts of re-sistance against the ‘imperial centre’ per se. Rather, we must understand them asdirected against the efforts being made by the landed elites of the district to useritual and spectacle as a way of enhancing their own standing and access to bene-factions from the imperial centre. If religious practice was a communicative mediumthrough which provincial elites could strengthen the ties that bound them to their su-periors, a failure of conformity of those beneath them in the social order threatenedto expose them as unable, in turn, to elicit respect and obedience on behalf of thosesuperiors.12

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

688 Gender & History

The biological family and the family of faith

What Perpetua tells us about her prison experience seems to reflect what we knowabout Roman practice in handling criminals. Despite her youth, she is taken away fromher family and kept from her baby, who is young enough still to be nursing. At first,she seems to be held in domestic custody, not at home but in the house of a personof high standing. She is then transferred to a prison that she describes as dark andfrightening. Her consolation there is the company of the others who are also beingheld.

Yet Perpetua knows she will be remembered. It is clear that she leaves her story asa gift to others whom she hopes can take strength from the strength she found duringher ordeal. She explores her fears and experiences in a way that she hopes will havevalue for others. What she suffers, she suffers as part of a group who stand with herand sustain her, and she knows that her own courage will in turn be a resource forothers who come after her. And she is sustained, too, by a vivid sense that the spiritof God is with her. She knows this from the dreams and visions which come to herduring her days in prison, and she knows it from her own ability to act with unexpectedcourage.

Perpetua had a baby who was with her during part of her imprisonment, andshe says that his welfare was her greatest cause for anxiety. Roman women of theupper classes tended to have wet-nurses for their babies, so the fact that Perpetua wassuckling the child herself tells us something about her. She may have come from anold-fashioned family who prized the old Roman custom of a simple and austere life, inwhich women worked at the loom and tended to their families personally, even if theywere rich enough to have numerous servants. But it is more likely that it is evidenceof modest circumstances: she tells us that her father warned her that the baby was notlikely to survive after her death, and this may imply that the family did not commandthe resources to hire a wet-nurse.13

The baby also raises a troubling question: where was Perpetua’s husband? Inorder to understand his absence, we must first of all establish whether the father ofher son was indeed her husband. The question is not as scandalous as it may seem,even when asked about a woman who would prevail in the arena as one of the greatearly heroines of the Christian faith. The reason we have to consider whether Perpetuawas married is that her memoir implies strongly that she was not. The details of thecustody arrangement which she makes for her baby make it clear that the child wasborn out of wedlock. She arranges that her mother and her brother will take care ofthe baby after her death, despite the fact that if she were married (even if widowed) itwould be her husband’s family, and not her own, who would have the right and dutyof care. In a union between free unmarried partners, the maternal grandfather wouldhave undisputed control and undisputed custody, should the two parents cease to livetogether. If a man wished his own father to have control – or if a legally independentman wished to have control over his own child – he was required to contract a iustummatrimonium with the woman whom he wished to act as mother. In Roman law, thewife or her family could never against his will gain custody of a man’s child born frommarriage, and at the same time the biological father or his family could not acquirecustody against the will of the mother or her family if the child was born from anunmarried union. This was a matter of logic, since the essence of marriage lay in a

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 689

man’s wish to secure patria potestas with respect to the children born of the union.Indeed, it was his ‘marital intent’ with respect to the status of the children that led theunion to be classed as matrimonium.14

It will be remembered that the later editor declared firmly that Perpetua had beenmarried to the baby’s father. But paradoxically, this can be taken as evidence that theeditor could see that something in Perpetua’s situation did not look right. The editormay have noticed that there had been a mistake somewhere and have wished to restorea sense of order in the text. It is also entirely possible, however, that the editor waswriting at a later date, at a place and time where Roman law was not in force, andsimply did not notice the problem.

To a modern eye, it seems impossible that a committed Christian like Perpetuashould have had a child out of wedlock. But this objection does not hold much weight.There are two points that a modern reader needs to consider in order to understandwhy. The first is that a sexual relationship between a concubine of the lower classes anda man who had no need for heirs but nonetheless wished to live with her was viewedas an orderly and appropriate arrangement by the Romans as long as the woman didnot expect to enter upper-class society. It was not looked down upon as intrinsicallya relationship of sexual promiscuity: if anything, taking an established concubine wasseen as a means by which a man who was too young or too poor to marry could stayout of sexual trouble.

If there was a stigma attached to concubinage, it was a stigma of class. To actas concubine was not a role for a genuinely respectable woman: it was one of themany more or less exploitative roles which women of the lower classes could expectto be asked to play. As Susan Treggiari has put it, ‘Concubines were chosen preciselybecause they were socially ineligible for marriage’. The point of the liaison, unlike thatof marriage, was stable and ideally pleasant sexual companionship for the man, ratherthan the production of heirs, while for the woman it was a matter of access to a higherstandard of living, and ideally, but not necessarily, to informal protection and perhapseven affection.15 The concubine’s position was one of economic dependence and, inall likelihood, of social invisibility. If Perpetua’s partner was a person of means, it ispossible that not only she but her parents depended on his generosity, and this wouldhave contributed to her father’s desire to see her return to playing the role expectedof her. A respectable man might well want to distance himself from a woman whofound herself on the wrong side of the law, and certainly her troubles would not be hisresponsibility. Her return to her father under such circumstances would have been asource of shame to her and it could well have brought with it the prospect of economicdifficulty as well.

The second point to consider is that Perpetua was a catechumen. It may well bethat her sexual attitudes had shifted dramatically since the time of the baby’s birth,depending on when she began her programme of Christian instruction. The second-century Christian philosopher Justin Martyr tells a story of just such a case from thetime of the Emperor Hadrian (d.138).16

In Justin’s story, a woman who was married to a dissolute husband initially sharedhis wild life, but when she fell in with the Christians and began to study their teachings,she decided she must distance herself from this way of life. Eventually this led her todivorce him. Justin says that she tried at first to stay on with him, in hope of having agood influence on him, but when it became clear that it was simply beyond her powers,

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

690 Gender & History

she filed for divorce. At this point, the husband denounced her to the authorities as aChristian, which is how the conflict came to Justin’s attention. Although she seems tohave escaped punishment, the complaint against her led to the arrest of her teacher,Ptolemaeus, who was subsequently executed as a criminal. It is a curious story, andnothing else is known about the woman, her husband or her teacher. But the storyillustrates the point that converts to Christianity sometimes changed their lives quiteradically, and that these changes were perceived as sometimes eliciting retaliation bythose who found the change disruptive.

It is certainly possible that Perpetua’s conversion led her to re-evaluate her re-lationship with her baby’s father, and perhaps even to an open break. This could bewhy there is no sign of him anywhere in her narrative. But even if there had been arift between Perpetua and her husband over her Christian conversion, and one or theother had initiated a divorce – Justin’s story above shows that the Christian womenof Perpetua’s day were able and willing to initiate divorce proceedings – custody ofthe baby would have remained resolutely with the father, or with his own male kinaccording to the rules of patria potestas. So it remains unlikely that the pair had beenmarried.

At the same time, we must remember that even if Perpetua were married, underthe Roman law of the second century CE, she herself belonged to the family of herfather.17 This meant that she could count on his protection and must in principle obeyhis authority, although there was of course no way to force obedience upon a personwho was willing to be executed as a criminal. But the fact that Perpetua’s father, motherand brothers all feature in her narrative while her baby’s father does not, surely reflectsthe simple fact that her father was the person accountable for her under Roman law,whatever her marital status. It is only the failure of the baby’s father or relatives toclaim custody of the child that suggests the absence of the marital bond.

Awaiting trial

We first meet the martyr Perpetua as she is being held for questioning by theprocurator.18 She is held in a private house rather than a prison; this was entirelynormal. In the Roman Empire, a suspect would often be taken into custody by a trustedindividual of standing in the community, with the understanding that the prisoner wouldbe delivered up to the authorities for questioning when the time came.19 This mode ofcustody was in part a cost-cutting measure, since it meant that the state could expendonly very modest resources on building and staffing prisons. But it was also a wayof involving local landowners in the maintenance of law and order, an enterprise thathelped to remind them of where their own loyalties ought to lie.

It is possible that the house where she was initially held was an elegant one, sincethe individuals who acted on behalf of the state in this way were of the class whocontributed their resources to shoulder the burden of government in other ways as well.The very rich in Carthage lived in imposing villas, houses which can still be seen,with their magnificent mosaic floors, in the ruins along the sea front of the ancientcity near the Antonine Baths, and such elegant houses would certainly have had lessconspicuous rooms where individuals under suspicion could be held securely withoutcausing offence to the more distinguished guests.20 If visitors were allowed, this maywell have been at the discretion of the household slaves.

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 691

Perpetua’s father’s visits may have been intended as visits of consolation, but ifso, they quickly turned sour. A difficulty of her imprisonment which Perpetua may nothave anticipated was the difficulty she faced in convincing her parents not to regret herdeath, but instead to accept it with equanimity and to rejoice in the task of watchingover her infant son after her death. We have no way of knowing whether Perpetua’sparents were pagan or Christian. Scholars have often assumed that they were pagan,because her father is very firm about his wish that Perpetua should do what she isasked to do by the imperial officials. But of course it is possible that Perpetua’s fatherwas himself a Christian, but a Christian of the kind – like many in the pastoral lettersof third-century bishops – whose love for the faith did not quite extend to wishingto see his child die a horrible death. This was not necessarily a matter of cowardice.Many Christians thought of themselves as law-abiding citizens, and may well have felta genuine repugnance at the idea that they should allow themselves to be branded asenemies of the state.

There seems to have been an understanding that if she and her fellows werecooperative and willing to make a burnt offering of incense, then the charges would bedropped. Perpetua paints a poignant scene of her father’s attempt to get her to acceptthis offer:

While we were still under arrest [she said] my father out of love for me was trying to persuade meand shake my resolution. ‘Father’, said I, ‘do you see this vase here, for example, or water-pot orwhatever?’ ‘Yes, I do’, said he. And I told him: ‘Could it be called by any other name than what itis?’ And he said: No’.21

Here, Pereptua understands that her father’s intentions are good, and at the outset shehas compassion for him. At the same time, she cannot give in. She has already begunto steel her mind against what she knows will be the form of her interrogation somedays later. She will be asked ‘Are you a Christian?’ and she will answer, ‘Yes, I am’.Perpetua presents her dilemma as both no more and no less than a problem of naming:whether she should allow herself to be let off the hook by allowing her offensivereligious views to be passed over in silence. Her next words, however, are firm, andthey make it clear that she intends to hold her ground. She responds to her father:

‘Well, so too I cannot be called anything other than what I am, a Christian’. At this my father was soangered by the word ‘Christian’ that he moved towards me as though he would pluck my eyes out.But he left it at that, and departed, vanquished along with his diabolical arguments. For a few daysafterwards I gave thanks to the lord that I was separated from my father, and I was comforted by hisabsence.22

This encounter seems gratuitously painful: a visit like this from her father could onlyadd to her distress instead of offering support or consolation. At the same time, it ispossible that this painful encounter offered something like a catharsis for the tensionshe felt in looking forward to her interrogation. Focusing her attention on the familiarproblem of her impossible father may, paradoxically, have helped her to keep hercourage up.

Why did Perpetua feel empowered, one wonders, to talk back to her father soboldly? It was certainly not the behaviour expected of a Roman daughter, and herfather’s furious reaction shows that he found it galling.23 There was some concernamong both pagans and Christian writers that certain Christians were in the business

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

692 Gender & History

of encouraging disobedient wives and daughters to think for themselves in a way thatwas dangerous to the fabric of a society that placed importance on the authority offathers, and the episode above could easily be taken as evidence that this was the case.But there is, of course, logic in Perpetua’s stance. If she was going to stand for the faithas a martyr, she would have to stand firm in the face of men far more powerful thanher father, men who were accustomed to intimidating persons far more powerful thanherself.

The reader is perhaps being asked here to see Perpetua as practising on herfather – the person of authority most familiar to her – as she prepared herself to standup not only against the emperor’s legal representative but against the very gods ofRome. If she could hold her ground against her father, she might have a fightingchance of holding her ground when it came to the formal interrogation. (In the event,she seems to have been successful: the Christian community in Carthage would laterremember her as a martyr of extraordinary courage.)

Later, Perpetua tells us she was moved to a prison. Here, we find another sign thatshe did not come from an imposing background: the accommodation was by no meansappropriate to a person of rank.

A few days later we were moved to the prison, and I was terrified. I had never before been anywhereso dark. What a difficult time it was! With the crowd the heat was stifling . . . and to crown it all, Iwas tortured with worry for my baby.24

The sense of community meant everything to the would-be martyrs, who werefaced with isolation and intimidation. Under the difficult conditions of the prison, anascetic discipline allowed them to prepare for physical pain and the most importantresource was the lore that offered an enabling narrative to reconfigure the meaning ofthe ordeal:

A few days later there was a rumour that we were going to be given a hearing. My father also arrivedfrom the city, worn with worry, and he came to see me with the idea of persuading me. ‘Daughter’,he said, ‘Have pity on my grey head – have pity on me your father, if I deserve to be called yourfather, if I have favoured you above all your brothers, If I have raised you to reach this prime ofyour life. Do not abandon me to be the reproach of men. Think of your brothers, think of yourmother and your aunt, think of your child, who will not be able to live once you are gone. Give upyour pride! You will destroy all of us! None of us will ever be able to speak freely again if anythinghappens to you!’25

Perpetua tells us that she comforted him but that he went away unable to understandwhy she felt she had to sacrifice herself, even putting the rest of the family at risk assympathisers of an illegal and potentially dangerous cult.

Here we need to stop and try to understand the father’s point of view. By allowingherself to be condemned and publicly executed Perpetua was indeed endangering therest of the family. In allowing herself to be executed for a crime that carried connotationsof something akin to political treason, Perpetua knew she would place her survivingfamily at risk in the context of the patronage and mutual surveillance governing Romancivic life.26

The hierarchical reversal implied by this scene was certainly damaging to thefather’s sense of ‘face’, and the fact that Perpetua was willing to reduce a Romanpaterfamilias to begging, rather than ordering, her to conform to accepted social normswould have sent chills down the spine of many readers. The father’s plea, ‘Do not

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 693

abandon me to be the reproach of men!’ would refer to a politically damaging loss ofhonour were he a man of standing, but even a person of comparatively modest standingwould have feared the bullying and intimidation that might follow once he was knownto have failed to control the members of his household.

The interrogation

Now we come to what is in many ways the crucial moment of Perpetua’s ordeal.‘One day while we were eating breakfast we were suddenly hurried off for a hearing.We arrived at the forum, and straight away the story went about the neighbourhoodnear the forum and a huge crowd gathered’.27 The crowd was not part of the officialprotocol, but its presence, with its restless energy and the eyes of the curious – andprobably hostile – spectators, will have added considerably to the intimidation felt bya defendant who was not already a hardened criminal. Another early martyr text fromNorth Africa, the Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs, refers to a hearing before the governor astaking place in secretario; there seems to have been a secretarium or council chamberin the lawcourts, as there was in other major public buildings. But in this case, theinterrogation seems to have offered a public spectacle.

As Perpetua approached the Forum of Carthage, she could be expected to feel amixture of awe and disquiet at the grandeur of the Roman colonial power. The RomanForum stands in the Acropolis of Carthage, a plateau at the summit of the Byrsa Hilloverlooking what is now the Bay of Tunis. Where exactly Perpetua’s hearing tookplace is uncertain. It is likely that it was in the Roman lawcourts, along the easternend of the Forum, facing the sea. An earlier visitor, Aeneas, had marvelled at Dido’scitadel on the same site in a poem written not long after the founding of the Augustancolony there in 29 BCE.28

Whether or not such associations were in play, an ancient reader would have beenaware of the effect such majestic public buildings would have had on a young woman,especially one who had never had reason to enter them before. Certainly, the lawcourtswere designed to be intimidating. On entering, one had to cross an immense vaultedhall whose roof was supported by dozens of massive columns.29 Even the lawyerswhose work brought them there daily would not have been immune to the effect of thiskind of Roman public architecture. It was calculated to remind those who entered ofthe power of Rome, and no expense had been spared in pursuing this aim.

Perpetua mentions that when she was summoned, the governor MinuciusTiminianus had recently died and in his place, the procurator Hilarianus, the seniortax-collector in the province, was officiating.30 As the person responsible for ensuringthat the agricultural wealth of Africa was safely collected and shipped to Rome to feedthe urban population, Hilarianus was acutely conscious of Rome’s need for peace andprosperity in Africa. What we know of him from other sources suggests that he wasa severe judge, acutely concerned with stamping out any resistance to the imperialauthority.31

Like many Roman magistrates, Hilarianus probably saw the Christians – when hethought about them at all – as a subversive sect who might well intend to overthrowthe government. It was his job to stop them before they got started: the Romans hadnot fought for the fertile grain-fields of Africa in order to hand them over to a rag-tagcompany of prophets from the market towns. We will see below that it was Perpetua’s

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

694 Gender & History

refusal to ‘offer sacrifice for the welfare of the emperors’ that formed his motive forcondemning her and her companions to the beasts.

As she recounts it, Perpetua’s interrogation with Hilarianus was short and sharp.She tells us that her interview consisted of only two questions, and this is entirelypossible. The procurator’s secretaries would have collected evidence and briefed himthoroughly, since he would normally have dozens or even hundreds of cases to hearin a single day. Each case – even the individuals among Perpetua’s own cohort ofcatechumens – needed to be processed individually. ‘We walked up to the prisoner’sdock. All the others when questioned admitted their guilt.’

Perpetua’s interrogation was complicated by her father’s appearance, still besidehimself in his distress: ‘Then, when it came my turn, my father appeared with myson, dragged me from the step, and said, “Perform the sacrifice – have pity on yourbaby!”’32 We have no way of knowing whether the father’s actions were a sign of hisunbalanced mental state, or a performance calculated to signal to the authorities thathe had done everything in his power to stop Perpetua. It is possible that in this way, hebelieved he could protect his surviving family from the displeasure of the authorities.

Now, finally, we come to Perpetua’s much-awaited exchange with the procurator.Despite her father’s effort to dissuade her, he cannot control how she will respond tothe procurator’s questions. It is worth citing the key exchange in full:

Hilarianus the procurator, who had taken up judicial powers in place of the deceased governorMinucius Timinianus, said, ‘Have pity on your father’s grey head; have pity on your infant son.Offer to sacrifice for the welfare of the emperors.’‘I will not’, I responded.‘Are you a Christian?’ said Hilarianus.And I said, ‘Yes, I am’.33

After this brief exchange, Perpetua’s father breaks in, trying to undo the damage createdby his daughter’s brazen refusal to acknowledge the authority of Rome.

The reader is not quite prepared for what happens next: ‘When my father insistedon trying to dissuade me, Hilarianus ordered him to be thrown to the ground andbeaten with a rod’. It is the beginning of the brutal treatment that she and her familywill experience as a result of her act of defiance, and it seems to suggest, again, thefather’s low social status, since the honestiores were not subject to corporal punishmentunder Roman law.34

Perpetua’s reaction shows that she is not entirely without feeling. ‘I felt sorryfor my father, just as if I myself had been beaten. I felt sorry for his miserable oldage’. She will have known that her family’s future was bleak as a result of her actions.Nevertheless, she closes the scene with another surprise: ‘Then Hilarianus passedsentence on all of us: we were condemned to the beasts (ad bestias), and we returnedto the prison in high spirits’.35

To our sensibility, this is a non sequitur: how can the condemnation have madethem happy? Yet for Perpetua and her companions, it was important that they hadpassed the first hurdle of their contest. They had stood before the most fearsome figurethe Roman authority in North Africa could produce and they had not been foundwanting. Now, they must prepare themselves to win glory in the arena on behalf oftheir God.

From this point forward, Perpetua’s memoir takes on an almost hallucinatoryquality. From an account of her encounters with the authorities, it becomes a record

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 695

of the dreams and visions that came to her in the days before she faced the beasts.Perpetua clearly believed that these dreams contained signs sent from heaven in orderto guide her and to help her to understand what she was being asked to do, and thelater Christians who preserved her prison memoir seem to have accepted this.

The first of her dreams is in many ways the most painful and evocative, for itconcerns one of the children in her family – her own brother – who had died a terribledeath, aged seven, of cancer:

Some days later when we were all at prayer, suddenly while praying I spoke out and uttered thename Dinocrates . . . at once I realised I was privileged to pray for him. I began to pray and sighdeeply for him before the Lord. That very night I had the following vision.36

It is through this dream that she discovers that she has been given the power toheal. The child appears to her scarred and suffering from a state of desperate thirst; inher vision, Perpetua is able both to heal the wound and to give the thirsty child accessto a fountain whose rim had been beyond his reach. Perpetua turns from her vision ofDinocrates to tell her reader that the power within her and her companions has beenrecognised from an unexpected quarter. Pudens, the prison governor, has begun torevere them and to try to help them, allowing visitors to come to the prison to honourthe martyrs.

But as the day of her contest in the arena approaches, Perpetua must contend withone last visit from her father. Again, his conduct is not really what we expect froma Roman paterfamilias; his attempts to steer his daughter’s will are wilder and moredesperate than one might anticipate:

Now the day of the contest was approaching, and my father came to see me overwhelmed withsorrow. He started tearing the hairs from his beard and threw them on the ground; he then threwhimself on the ground and began to curse his old age and to say such words as would move allcreation. I felt sorry for his unhappy old age.37

Merely by withholding the proper obedience expected of a Roman daughter, Perpetuahas reduced him to a state of helplessness. What she tells us next suggests that sheis aware, at least at an unconscious level, that she has undergone a profound trans-formation and has acquired the power to prevail over even the most frightening ofmen.

Resisting Rome or resisting thy neighbour?

In trying to understand Perpetua’s encounters with her father, it is worth trying toperceive the imaginative framework against which her actions were measured. Wehave seen that Perpetua herself saw her father as aligned, at least in some measure,with the authority of the state. In her experience, his authority stands as a moreaccessible layer of the same disciplinary pressure exerted by the procurator Hilarianus.

But what about the point of view of Perpetua’s father? Here, the question of socialclass comes into play. The fact that he was beaten by the agents of the procuratorHilarianus suggests that he was one of the humiliores, the social class against whomdegrading physical punishment could appropriately be used by social superiors. Thisinference is compatible with the low social status implied by the likelihood that Perpetuawas unmarried.

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

696 Gender & History

If Perpetua’s father had the procurator to fear, other figures in a more locallandscape will also have cast their shadow. A recent study by Judith Perkins hasclarified how the patriarchal elite of provincial cities sought to present themselvesas benevolent fathers of orderly dependents in their region, reflecting an ‘ideologicalindustry’ centred on the concept of homonoia.38 In his Roman History, one of the earlythird-century governors of Africa, Cassius Dio, suggested that in 29 BCE Maecenashad proposed to Augustus that ‘the noblest, the best, and the richest men’ of theprovinces should be co-opted into the Senate in order to act as ‘co-workers (synergois). . . and sharers (koinonoi) in your Empire’.39 The work of these provincial elites indisciplining their inferiors was likened by other writers to that of a head of householdmaintaining discipline among his servants.40

Rives has argued that the principal agents of religious institutions in RomanNorth Africa were the members of the ordo of decurions: prosperous regionally basedlandowners of the kind who would have had membership on the city councils andheld magistracies and priesthoods as well as sponsoring games. Games such as thoseheld to celebrate the birthday of the emperor’s son, at which Perpetua tells us sheexpects to be executed, would have been sponsored by curial landowners.41 Generally,games were offered by magistrates as part of their opportunity to cultivate personalauthority and high standing while in office.42 Offerings associated with the cult of theimperial family were part of a broadly based system in which numerous families ofhigh standing made what probably amounted to competitive displays of loyalty.43

As elsewhere in the Empire, religion in North Africa was characterised by thiskind of competitive sponsorship and gift giving. Giving games, fulfilling priesthoods,dedicating altars: all these were ways for a provincial landowner to claim a privilegedconnection to the symbolic capital of empire. The case of P. Perelius Hedulus, afreedman who established a prosperous brick and tile workshop in Carthage during thereign of Augustus and used his wealth to pay for a massive altar to the same emperoron the Capitol there, reveals the pattern. The prosperity of Hedulus reflected the wealththat Augustus had managed to extract from Africa, and at the same time the fact thatAfrican elites were allowed to take their share. By encouraging benefactions such asthe altar of Hedulus, the proconsuls at Carthage were able to harness the self-interestof the elites on the empire’s behalf.’44 By allowing an ex-slave like Hedulus to claima link to the power and glory of the emperor, the authorities permitted his wealth andallegiance to be put in turn to the service of the emperor’s power. Rives remarks that ‘itis clear that Hedulus himself benefitted from his shrine much more than the emperorever did’, but at the same time the emperor benefited from the successful installationof networks of expectation that allowed local elites to claim identity with the projectof empire.45

So it is fair to imagine that, like Hedulus, the sponsor of Geta’s games was alocal who wished to enhance his own standing. He was probably a member of thecuria of Carthage, for whose ambitions the success of the games could have importantrepercussions.

A chilling aspect of Perpetua’s situation was the fact that the procurator Hilarianuswas in a position to sell condemned criminals to these landowners, precisely in orderto allow them to offer ever larger numbers of individuals to the beasts during theirgames. In 176 CE (or early 177), the Emperor and the Senate had cooperated in ameasure designed to relieve the provincial landowners of some of the expense of

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 697

hosting gladiatorial games. They were now able to purchase condemned criminalsfrom the imperial procurators at the cost of six aurei per head, or one-tenth of the priceof hiring a fifth class gladiator, with proportionate savings for the higher grades.46

But the selling of criminals to die in the arena also had an ideological purpose. Allparties knew that in order to maintain his dignity and the public order, the procuratormust crush those who called attention to themselves by refusing to bow to his authority.The point was to put a stop to the challenge posed by their disobedience but it wasalso an act of communication to the civic body assembled in the amphitheatre. Byexecuting the miscreants in a way that was both brutal and humiliating, the crowd wasboth entertained and discouraged from sympathising with their cause. More difficultto understand is the relation of power and humiliation between the civic elites and thelesser mortals whom they bought in order to display them as they faced destruction.The games have frequently been seen as assertions of the power of empire, and thismust be right. But they were also an assertion by certain families of their own rightto stand with Rome against their own inferiors, the population with whom they wereyoked by geography, if not by sympathy.

Perpetua and the Egyptian

Perpetua’s final vision shows that for all her bravura, the fact has not escaped her thatthe punishment for her act of defiance will be a hideous death. The Christian apologistTertullian, who was living in Carthage at the time of Perpetua’s execution, argued thatthis policy of humiliating the Christians as criminals in the arena could only backfire.Men and women who knew their God would sustain them had nothing to fear, hesuggested, and so they could not be humiliated. In his Apology (written c.197–98 CE),Tertullian had warned an earlier Roman governor that ‘whenever we are mown downby you, the blood of Christians is seed for the Church’ (Apology, 50). This ideal wasinspiring, but at the same time it raised the bar for those who intended to face the beaststhemselves. Perpetua’s memoir suggests that as the time of the contest approached,even her unconscious mind was working to prepare her to face her ordeal with valour:

The day before we were to fight with the beasts I saw the following vision. Pomponius the deaconcame to the prison gates and began to knock violently . . . And he said to me, ‘Perpetua, come;we are waiting for you’. Then he took my hand and we began to walk through rough and brokencountry. At last we came to the amphitheatre out of breath, and he led me into the centre of thearena. Then he told me, ‘Do not be afraid. I am here, struggling with you’. Then he left.47

The idea, here, that she would be sustained by a powerful presence, was one thatreached back to the Apostle Paul’s idea that ‘I have been crucified with Christ and I nolonger live, but Christ lives within me’.48

Next, Perpetua turns to face what awaits her in the arena. ‘I looked at the enormouscrowd who watched in astonishment. I was surprised that no beasts were let loose onme; for I knew that I was condemned to die by the beasts.’ There is a surprise: ‘Thenout came an Egyptian to fight against me, together with his seconds. Some handsomeyoung men came along, too, to be my seconds and assistants. My clothes were strippedoff, and suddenly I was a man’.49 This is wholly unexpected.

What can we make of Perpetua’s statement that she became a man? At one level,we can see it as the logical development of a theme that has been present throughout

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

698 Gender & History

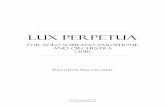

Figure 1: Carthage, the Roman amphitheatre (photo: David Mattingly).

the narrative: this is a woman who is fearless and refuses to accept the subordinaterole that might be expected of a Roman daughter. At another level, however, her self-transformation is a marker of the surreal quality of the vision world. In the logic ofthis world, she must prevail because she is fighting for God; her perception of herselfas a man is a sign of her growing confidence.50 Now she is ready to take on theEgyptian:

We drew close together and began to let our fists fly. My opponent tried to get a hold of my feet,but I kept striking him in the face with the heels of my feet. Then I was raised up into the air and Ibegan to pummel him without as it were touching the ground.51

We can notice a number of important things here. The first is Perpetua’s intenseinvolvement in the vision. It has clearly come to her in vivid detail, and one can almostfeel her thrashing as she tries to shake her feet free, in order to use them against heropponent.

The second is that Perpetua herself has a clear idea of what takes place at suchcontests. She knows what men do when they wrestle, and there is none of the uncertaintyabout the goings-on in the arena that one might expect from a young woman who hadlived most of her life indoors. Thuburbo was in fact a large enough town to haveits own Roman amphitheatre, so she may well have gone along to watch wrestlingmatches there during her childhood, even if her own contest would be held in the moreprepossessing amphitheatre at Carthage (Figure 1). Certainly, this was not a womanwho was afraid of the world of men.

As Perpetua looks ahead to her day in the arena, she knows that the civic order willbe re-established through the destruction of those who have raised their voices againstRome. It will not have escaped her, however, that the fatal games of the amphitheatreare a perfectly suited vehicle for the message of asserting the city’s willingness tobe governed by the Emperor’s authority. The amphitheatre itself is one of the greatmonuments of Roman power in North Africa and it is a venue in which the citizensregularly re-affirm, publicly and splendidly, their desire to attract the benefits accordedby this power to those who do its bidding.

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 699

At every step along the way, Perpetua’s story has been intertwined with thatof Rome in Africa. Even the most intimate details of her story, such as the painfulrelationship with her family, are somehow bound up with the presence in the land ofa power that has changed life immeasurably for both the urban and rural populations.Even the reassuring vision of the little brother finally able to slake his thirst remindsus of the Roman power in the land. A ubiquitous sign of Roman occupation – and theelement which makes us understand why so many Africans were happy to accept theyoke of Rome – could be seen in the great works of Roman civil engineering. Romanaqueducts fed baths and fountains in virtually every town across the land. The basinfrom which the child Dinocrates was able to drink, in Perpetua’s vision, was as mucha sign of Roman occupation as was the amphitheatre in which she herself, his sister,would meet her death.

It is difficult to assess the significance of gender in Perpetua’s understanding ofherself as a subject of Roman power. Certainly, we have seen that she perceived thepatriarchal structures of Roman authority as standing in alignment: her father’s wishwas to steer her toward obedience of the procurator, and the procurator in turn wasworking on behalf of the emperor. And where Perpetua imagines herself as able todisrupt, and ultimately to triumph over, these carefully aligned structures of domesticand civic authority, it is noticeable that she does so in the context of a vision in whichshe becomes a man, and a specimen of virility at that. But if she understands her ownrefusal to perform as expected as a challenge to Roman power, it is not necessarily thecase that the terms of this power are in question. She closes her vision of the Egyptianwith an assertion that the Roman power is subordinate, in turn, to the celestial hierarchy;she would fight on behalf of a power stronger even that that of Rome. ‘Then I awoke.I realised that it was not with wild animals that I would fight but with the Devil, but Iknew that I would win the victory’.52

The long future

It remains to consider one last scene handed down by Perpetua’s editor. It is possiblethat the scene reflects an element of eyewitness tradition, but it may also be the workof a later writer in light of his or her independent knowledge of the Roman games, orindeed a Christian fantasia – if the editor is writing some time later – on the despicablepleasures of the pagans. This is the notorious incident in which Perpetua and hercompanions were required to dress as priests and priestesses of Saturn and Ceres:53

They were then led up to the gates and the men were forced to put on the robes of the priests ofSaturn, the women the dress of the priestesses of Ceres. But the noble Perpetua strenuously resistedthis to the end. ‘We came to this of our own free will, that our freedom should not be violated. Weagreed to pledge our lives provided that we would do no such thing. You agreed with us to do this.’Even injustice recognised justice. The military tribune agreed. They were to be brought into thearena just as they were.54

As K. M. Coleman has suggested, Perpetua and her companions would certainly havewanted to avoid playing such a role: ‘as priests of Saturn and priestesses of Ceres theywere attendant upon the deities of annual sowing and reaping, and at the same time theythemselves, about to die and enter the underworld, would constitute the sacrifice’.55

Perpetua’s editor does not comment on this significance, choosing instead to playit as the context for a pithy saying about justice and injustice. Whether the episode took

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

700 Gender & History

place in reality or not, its role in the narrative is as an occasion for the blazing faithof Perpetua and her party to suffer a threat of degradation and to emerge triumphantthanks to the bold intelligence of the martyrs.

Perpetua’s memoir ends with the vision of her struggle with the Egyptian, on theeve of her appointed day in the arena. The story of her death the next day, alongsideher companions, will be told afterwards by the anonymous editor, who claims to bean eyewitness to her brave conduct when she was thrown to the beasts, although thereis every reason to suspect that a later writer put together the account on the basis oflegend or oral tradition. The author of this narrative takes pains to emphasise Perpetua’sfeminine modesty as well as her bravery: it is almost as if he or she has read Perpetua’sown account and been somewhat alarmed by her vision of herself as a naked malewrestler in a wrestling match. This stands in sharp contrast to the vivid, bold andunapologetic voice of the martyr herself.

Perpetua’s boldness reveals itself, too, in the honest way in which she grasps theproblem of how her story has already spun beyond her own control. Her voice willendure in a future beyond her death, but in a form chosen by others, to serve the needsof later communities unknown to her and beyond her imagining. If her willingnessto die for her faith shows physical and moral courage, her last words are brave in adifferent way: ‘This is what happened up to the day before the contest. As for what isto happen at the contest itself, let him write of it who will’.

NotesThanks are due to the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and to Thomas Heffernan for theopportunity to draft this text in the context of the NEH Summer Seminar on Perpetua and Augustine held inTunis, July–August, 2010, and to members of the seminar for lively discussion on many of the points addressedhere. I am particularly grateful to the friends and colleagues whose thoughtful comments on earlier drafts ofthe text did much to temper its failings, though none can be held responsible for those that remain: StephanieCobb, James Corke-Webster, Jennifer Ebbeler, Lin Foxhall, Barbara Gold, Amalia Jiva, Conrad Leyser, VasilikiLimberis, Candida Moss, James Rives and Katie Wood Peters. Finally, I am grateful to Dr Nejib Ben Lazreg forsharing his expertise on the archaeological remains of Roman Carthage.

1. It is Perpetua herself who tells us that she expected to be executed as part of the celebrations for Geta’sbirthday. Because her memoir (Passio 7.9) refers to the games in question as military games (munere. . . castrensi) some scholars have imagined that the games would have been held in a temporary woodenmilitary amphitheatre but there is no specific evidence to support this idea. Geta was the target of a damnatiomemoriae by his brother Caracalla after his assassination in 211, so the survival of this reference to gamesin his honour in Perpetua’s memoir, while he was still alive, is a point of interest. Perpetua mentions atPassio 6 that her trial took place shortly after the death of the proconsul Minucius Timinianus, but he isotherwise unattested.

2. A summary of the problem, with relevant bibliography, can be found in Thomas J. Heffernan, ‘Philologyand Authorship in the Passio Sanctarum Perpetuae et Felicitatis’, Traditio 50 (1996), pp. 315–25.

3. In light of the focus here on Perpetua as narrator, it is beyond the scope of the present article to explore therelationship between author, implied author and narrator as understood by contemporary critical theory;see, for example, Seymour Benjamin Chatman, ‘In Defense of the Implied Author’, in Seymour BenjaminChatman, Coming to Terms: The Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film (Ithaca: Cornell UniversityPress, 1990), pp. 74–89; Dorrit Cohn, Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousnessin Fiction (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978).

4. See the introduction to Jacqueline Amat’s edition of the text, Passion de perpetue et de felicite suivi desactes, sources Chretiennes 417 (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1996), pp. 67–78. If the third party account oftheir deaths was indeed an eye-witness account it could suggest either that the editor wrote not long afterthe martyrs’ deaths or that it had been collected by the later editor along with the other two narratives. It isalso possible that the martyrdom component, which bears some traces of literary shaping, was written by

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage 701

a much later editor as a pious fiction designed to help readers to imagine the authors of the prison diariesas flesh-and-blood martyrs: this is an issue I intend to explore in a later study.

5. My own earlier study, ‘The Voice of the Victim: Gender, Representation, and Early Christian Martyrdom’,Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 80 (1998), pp. 147–57, does not take account of this point as fully asI would now wish to.

6. Passio 2. I have followed the translation of Perpetua’s text in Herbert Musurillo, The Acts of the ChristianMartyrs (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), pp. 106–31, with occasional modifications.

7. On this point, see Kate Cooper, ‘Closely Watched Households: Visibility, Exposure, and Private Power inthe Roman Domus’, Past & Present 197 (2007), pp. 3–33; Margaret Y. MacDonald, Early Christian Womenand Pagan Opinion: The Power of the Hysterical Woman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

8. See Judith Perkins, Roman Imperial Identities in the Early Christian Era (London: Routledge, 2009).Postcolonial anthropology is also helpful here: on ‘rival cognitions’ see, for example, C. A. Gregory,Savage Money: The Anthropology and Politics of Commodity Exchange (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic,1997), pp. 25–8; C. A. Gregory, ‘Cowries and Conquest: Towards a Subalternate Quality Theory ofMoney’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 38 (1996), pp. 195–217, here p. 203, citing RanajitGuha, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983).

9. Richard Gordon, ‘The Veil of Power: Emperors, Sacrificers, and Benefactors’, in Mary Beard and JohnNorth (eds), Pagan Priests: Religion and Power in the Ancient World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press,1990), pp. 199–231.

10. S. R. F. Price, Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 1984), p. 100.

11. Price, Rituals and Power, p. 100.12. See Kate Cooper, ‘Insinuations of Womanly Influence: An Aspect of the Christianization of the Roman

Aristocracy’, Journal of Roman Studies 82 (1992), pp. 15–64; Cooper, ‘Closely Watched Households’.13. Passio 5.14. Susan Treggiari, Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 37–80.15. Treggiari, Roman Marriage, p. 52.16. Justin Martyr Second Apology 2.17. Manus marriage, the form by which the woman passed to the authority of her husband, had become rare

by the first century BCE: Treggiari, Roman Marriage, p. 35.18. Passio 3.19. Julia Hillner, ‘Monastic Imprisonment in Justinian’s Novels’, Journal of Early Christian Studies 15 (2007),

pp. 205–37, here pp. 221–8.20. On these villas, see Aicha Ben Abed-Khader, Margaret A. Alexander and Guy Metraux, Corpus des

mosaiques de Tunisie, vol. 4: Karthago, Carthage: Les mosaıques du parc archeologique des thermesd’Antonin (Tunis: Institut national du Patrimoine, 1999).

21. Passio 3.22. Passio 3.23. For a survey of the recent literature on the father–daughter relationship, see Thomas Spath, ‘Cicero, Tullia,

and Marcus: Gender-specific Concerns for Family Tradition?’ in Veronique Dasen and Thomas Spath(eds), Children, Memory, and Family Identity in Roman Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010),pp. 147–72.

24. Passio 3.25. Passio 5.26. Cooper, ‘Closely Watched Households’, p. 8.27. Passio 6.28. On Virgil Aeneid 1.418–38 and the foundation of the Augustan colony at Carthage, see Paul McKendrick,

The North African Stones Speak (London: Routledge, 1980), p. 30.29. Pierre Gros, ‘Le forum de la ville haute dans la Carthage romaine, d’apres les texts et l’archeologie’,

Comptes-rendus de l’Academie des inscriptions et de belles-lettres (1982), pp. 636–58.30. Passio 6.31. James Rives, ‘The Piety of a Persecutor’, Journal of Early Christian Studies 4 (1996), pp. 1–25.32. Passio 6.33. Passio 6.34. On the differential justice of the period, see Perkins, Roman Imperial Identities, pp. 97–100 and literature

cited there.35. Passio 6.

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

702 Gender & History

36. Passio 7.37. Passio 9.38. Perkins, Roman Imperial Identities, pp. 62–67, citing Simon Swain, Hellenism and Empire: Language,

Classicism, and Power in the Greek World, A.D. 50–250 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), p. 181.39. Cassius Dio Roman History 52.19.2–3, cited in Perkins, Roman Imperial Identities, p. 63. For discussion

of Dio’s career, see T. D. Barnes, ‘The Composition of Cassius Dio’s Roman History’, Phoenix 38 (1984),pp. 240–55.

40. Dio Chrysostom Oration 38.15, cited in Perkins, Roman Imperial Identities, p. 66.41. Passio 7.42. An analogy might be the ludi Cereales of Carthage: according to James Rives, Religion and Authority in

Roman Carthage from Augustus to Constantine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 48: ‘They werepresented from 12 to 19 April [annually] by the plebeian aediles, and consisted of one day of chariot racesin the Circus preceded by seven days of lesser events, probably in the theatre . . . The games of Ceres wouldhave been preceded by an offering and some sort of procession, in which the priests of Ceres would no doubthave taken a leading role. It is even possible that they and not the aediles were responsible for presentingthe games, although in the Roman tradition games were always the responsibility of magistrates’.

43. Rives, Religion and Authority, p. 60.44. Rives, Religion and Authority, p. 56.45. Rives, Religion and Authority, p. 57.46. Senatusconsultum of 176 or 77 CE; CIL ii. 6278 = Dessau ILS, 5163, discussed in W. H. C. Frend,

Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church (Oxford: Blackwell, 1965), p. 5.47. Passio 10.48. Galatians 2: 20.49. Passio 10.50. The androgynous quality of early Christian heroines such as Perpetua has attracted the attention of numerous

scholars. Among the most influential studies are Wayne A. Meeks, ‘The Image of the Androgyne: SomeUses of a Symbol in Earliest Christianity’, History of Religions 13 (1974), pp. 165–208; Kerstin Aspergen,The Male Woman: A Feminine Ideal in the Early Church (Uppsala: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1990). On theexemplary manliness on display in the Roman arena, see Carlin A. Barton, ‘The Scandal of the Arena’,Representations 27 (1989), pp. 1–36.

51. Passio 10.52. Passio 10.53. For discussion, see Brent D. Shaw, ‘The Passion of Perpetua’, Past & Present 139 (1993), pp. 3–45; Aline

Rousselle, Porneia: On Desire and the Body in Antiquity, tr. Felicia Pheasant (Oxford: Basil Blackwell,1988), pp. 117–20.

54. Passio 18.55. K. M. Coleman, ‘Fatal Charades: Roman Executions Staged as Mythological Enactments’, Journal of

Roman Studies 80 (1990), pp. 44–73, here p. 66.

C© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.