A Constitutionalist Approach To Social Security Reform...A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH TO SOCIAL...

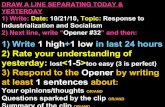

Transcript of A Constitutionalist Approach To Social Security Reform...A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH TO SOCIAL...

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH TOSOCIAL SECURITY REFORM

Thomas J. DiLorenzo

I. IntroductionIt is well known that the Social Security system embodies two

basic functions: welfare and insurance. Another well-known fact,which is often ignored in popular and academicdiscussions of SocialSecurity, is that the combination of the welfare and insurance func-tions creates an “inherent contradiction,” as described by Peter Fer-rara.1 Because Social Security has always pursued welfare objectivesas well as insurance goals, it operates on a pay-as-you-go basis—Social Security taxes paid into the system are not saved or investedas with real, private insurance, hut instead are paid out to currentrecipients, as in a welfare program. As a result, the Social Securitysystem provides insurance benefits in a very inefficient and inequi-table way, imposes major negative efl’ects on the economy, and severelyrestricts individual freedom. Since Social Security diverts billions ofdollars in savings to the current expenses of government, capitalinvestment is much lower than it would otherwise be, and conse-quently economicgrowth, national income, and employment are alsodepressed.2 Individual taxpayers are made worse off, since they losethe interest return they would receive iftheir money were invested—a return much higher than that earned on tax payments and benefitsfinanced by future generations.3

CatoJoicrnal, vol. 3, no.2 (Fall 1983). Copyright © Cato Institutc. All rights reserved.The author is assistant prokssor of economies, George Mason University, Fairfax,

Va, 22030.PeterJ. Ferrara, Social Security: The Inherent Contradiction (Washington, D.C.: CatoInstitute, 1980).‘See, for example, Martin Feldstein, “Social Security, Induced Retirement, anrl Aggre-gate Capital Accumulation,” Journal of Political Economy 82 (September/October1974); and ideni, “Social Security and Private Savings: hiternational Evidence in anExtended Life-Cycle Model,” in M. Feldstein and R. Inman, eds., The Economics ofPublic Sereices (New York: Halstead Press, 1977).31t has been estimated that the rate of return provided by the Social Security system isapproximately 10 to 15 percent ofthe return to private-sector alternatives. See Ferrara,chaps. 4 and 9.

443

CATO JOURNAL

Perhaps the most serious problem created by the Social Securitysystem stems from its coercive and compulsory nature. Because ofthe welfhre aspects of the benefit structure, some beneficiaries getmore than they are (actuarially) entitled to, while others get less. Ifthe system were voluntary, those getting less would opt out of thesystem, threatening it with bankruptcy. Because the program as it isnow constructed must be compulsory if it is to survive, politicaldecision ntakcrs insist that it must be run by the government, sincethe government is the only institution that has such powers of coer-cion. Thus, the program will always operate according to politicalrather than economic criteria. This politicization, in fact, is the basiccause of the program’s inherent instability, as will be discussedbelow.

Many writers have recognized the inherent instability of the SocialSecurity system and have prescribed various “solutions,” many ofwhich are aimed at separating the welfare and insurance functions.4

Martin Feldstein seems to appreciate more fully than others theimportance of separating the welfare and insurance elements. Hehas proposed placing the insurance portion of Social Security on afully funded basis with a self-supporting trust fund. But this proposalis also hound to be disappointing, should it be adopted, for it leavesthe insurance fhnction of Social Security in the domain of the gov-ernment sector and subject to the forces of political manipulation.

The objectivc of this paper is to explain the inherent advantages,in terms of equity and efficiency, of complete privatization or “de-nationalization’’ of the old—age insurance industry. As the title indi-cates, the discussion will present a “constitutionalist” perspectiveon Social Security reform. As in so many other areas, government’sexcursions into the old-age insurance industry have produced manyundesirable results. I contend that this situation has come aboutneither because the “wrong” people were in office, nor because theywere misinfbrmed, but because our democratic institutions are con-strained neither by law nor by stIong traditions regarding the appro-priate tasks of government.5 Government has expanded far beyond

See, for example, Joseph A. Feesmmm, Henry J. Aaron,and M id lae I K. Taossig, SocialSecoritij: Perspcctieesfor Reform (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1968); andAlicia H. Munnell, The future of Social Security (Waslnngton, D.C.: Brookings Insti-tutioll, 1977).‘The cousti tution alist perspective is in ost eomn‘only I inkerl with Friedrich A. H ayek,Law, Legislation, and Liberty, vol. 3, The Political Order of a Free People (Chicago:University ofCll,cago Press, 1979); and James M. Buchanan,Frecdo,n in ConstitutionalControct (College Station, rex.: Texas A&M U niversity l’rcss, 1977). For a recentdiscussion ofthe transformation ofideas regarding the appropriate role of govornlnentin the economy, see Bernard Siegan, Economic Liberties a lId tl,e Constitution (Chi-cago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

444

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH

its more limited role of protecting private property rights. It nowthrives on the game of interest-gronp politics, whereby one group’srights are destroyed to accommodate another’s in return for politicalsupport that helps keep the existing government in power. Thiswidening of governmentaJ powers is largely responsible for many ofthe destructive policies (such as Social Security) that we observetoday.

The remainder of the paper will discuss the effects of the changein the constitutional setting that has allowed the nationalization ofthe old-age insurance industry. Section II presents some of the rele-vant conceptual issues from a constitutionalist perspective and dis-cusses privatization of old-age insurance. Section III compares pub-lic and private provision of old-age insurance from a theoreticalstandpoint. Section IV explores the function of public advertising inthe provision of Social Security and contrasts itwith the role ofprivateadvertising. Section V examines the argunient that compulsorygovernmental provision is needed because of “market failures,” andsection VI offers a summary and conclusions.

II. Private versus Political Provision of Old-AgeInsurance: Some Conceptual Issues

The issue ofwhether old-age insurance is best allocated by marketor by political criteria is moot to those who understand the negativeconsequences of the attenuation of private property rights underpolitical resource allocation. Nevertheless, it is important to empha-size the profonnd differences between the market process and thepolitical process as mechanisms for allocating resources.

The market is a process in which individuals voluntarily interactwith one another in pursuit of their own interests. And with appro-priately designed institutions such as well-defined, enforced, andrespected property rights, freedom of contract, freedom of exchange,and the enforcement of contracts, self-interested behavior generatesa spontaneous order—an order chosen by no one; yet it tends tomaximize the subjective values of all the market participants. It is inthis sense that the market order can be termed “efficient.” The maxi-mization of subjective values, as individuals themselves perceivethem, is the result of the market process and is not something thatcan be defined or “maximized” by some outside observer. A pointworth emphasizing is that self-interested behavior does provide indi-viduals with incentives to cheat, to defraud, or to default, but asJames Buchanan6 has pointed out, laws, customs, traditions, or moral

°JamosM. Buchanan, “Notes on Polities as Process” (Paper presented at the 1983meeting of tlse Pnhlic Choice Society, Savannah, Ga., March 25, 1983).

445

CATO JOURNAL

precepts have been constructed or have evolved to limit such behav-ior in the market. Thus an overriding function of government is toestablish the “rules ofthe game,” and to define and protect propertyrights, the fi’eedom of exchange, and freedom of contract so as tofacilitate mutually advantageous trade.7 The successful performanceof this function, along with generally agreed-upon norms regardingthe illegitimacy ofcheating and defrauding one’s partners inexchange,strengthens the market process and enhances individual welfare.

By contrast, there simply are no such constraints imposed upon“political exchange.” It is rare indeed that a politician is prosecutedfor bribery, corruption, hand, or dishonesty. Who would create suchlaws, and who would enforce them but politicians themselves? Inpolitics, ownership rights are not respected. In fact, the state seemsto operate on the notion that those within government lay claim toall property rights, and have the power to rearrange these rights asthey see fit, This is not a “devil theory” of government. Politiciansand bureaucrats are, as individuals, no different from the rest of us,They prefer more rights to the use of resources to fewer and areutility maximizers, just as we all are. But the utility of the politicianor bureaucrat, operating in the world of “political exchange,” is notnecessarily enhanced primarily by ownership rights in some goodsor services, as in the private market. Politicians and bureaucrats usetheir positions in government to bestow special rights or privilegeson politically active individuals or groups in exchange for votes,campaign contributions, and other forms of political support.8 Thosewhose rights are consequently abridged are usually those who arenot well organized politically. The revocation or destruction of prop-erty rights is the business of modern politics, and politicians arecontinually seeking to expand the market for their “services.” Sta-bility in private property rights is anathema topoliticians andbureau-crats, for it imposes constraints on their abilities to accumulate powerand wealth.

The Social Security system currently consumes a large part oftaxable income and themefore represents a significant infringementof individual rights by government. Since the system is compulsory,individuals are denied the right to control a large portion of theirincomes. And, more important for our purposes, they are prohibited

‘This is not to imply that government is necessarily the only institution that can performthese tasks, Mall)’ have argued that private courts, for example, would he superior to

the present system.8For a more general discussion of tisis phenomenon, see M icIIaeI C. Jensen and wit—

ham H. Meekling, “Can the Corporation Survive?” Financial Anal ljstsJonrnal (Janu-avy/Fehmuaiy 1978): 31—37.

446

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPH0ACFI

from choosing other means of purchasing old-age insurance. Theimportant point is that by its very nature, compulsory governmentprovision of old-age insurance is “inefficient” and therefore reducesindividual welfare. Ifold-age insurance were provided privately, theappropriate role for government would be the more limited one ofprotecting economic liberties in that and other markets. Currently,the government has revoked those rights—rights that many through-outsociety have recognized as important. As Peter Ferrara has stated:

It should he apparent that the coercive nature of social secu-ityviolates all of these rights. It forces individuals to enter into con-tracts, exchanges, and associations with the government that theyshould have the right to refuse. It prohibits individuals From enter-ing into alternative contracts, exchanges, and associations with oth-ers concerning the portion of their incomes that social securityconsumes. It prevents individuals from choosing courses of actionother than participation in social security, although these coursesof action will hurt no one ... The program ... operates by the useof force and coercion against individuals rather than through vol-ontary consent. The social security program thus restricts individualliherty in major and significant ways.

From a constitutionalist perspective, it is the enforcement andprotection of these rights through the rule of law that is necessary toprevent government fi’om farther abusing its power by manipulatingthe Social Security system far political gain. Such a rule of law maybe either written or unwritten, hut it will only be enforced if it hasthe approval ofat least a majority of the electorate. In short, as arguedbelow, what is essential to meaningfully address the Social Securitydilemma is a change in the constitutional setting. Such a changewould require that citizens come to realize the importance of eco-nomic’ liberties, such as the fi’eedom tocontrol a lai-ge portionofone’sincome, and to prohibit the further political plundering of these andother freedoms. For once the government extends its powersbeyondthe protection of basic rights and enters the realm of legislation andregulation, more and more freedoms are denied, and individual wel-fare is reduced.

III. The Political Economy of Privatization: TheCase of Old-Age Insurance

Many taxpayers are made worse offbecause the old-age-insuranceindustry is monopolized by government. These individuals wouldtherefore benefit if privatization were allowed. Unfortunately, tax-

°Ferrara,p. 275.

447

CATO JOURNAL

payers are generally poorly organized politically and will thereforefind it difficult (though by no means impossible) to achieve privati-zation. Among the major beneficiaries of governmental control of theold-age insurance industry are Social Security Administration (SSA)bureaucrats. Bureaucrats are basically no different fi’om other indi-viduals; their primary objective is to enhance their own selfinterest.Public employees, however, face a starkly different institutional set-ting than their private-sector counterparts. This difference explainswhy government provision of old-age insurance is likely to he morecostly and of a lower quality than private provision. In the privatesector, the manager (of an insurance company) who tries to minimizethe cost to his customers is rewarded by profits, as cost reductionsincrease his price/costmargin. Profits may benefitthe manager directly,should he he a part owner of the firm, or indirectly in the form ofmore frequent promotions and salary increases. Further, the privatemanagers who do not strive to minimize costs and to produce a high-quality product will he penalized by the loss of profits. Manageriallabor markets also promote cost minimization, because the firms thatdo not reward managerial talent will lose that talent (along with theprofit-making opportunities) to competing firms.

The market for corporate control is yet another device that createspressures for cost-minimizing behavior, because managers who donot strive to maximize the value ofthe firm (by giving the consumerswhat they want at least cost) run the risk of being replaced throughthe mechanism of a takeover bid.1°Finally, the survivor principledictates thatthe private firms that do not strive toprovide high-qualityproducts at least cost in competitive markets will, in the long run,simply not survive. In sum, private-sector institutions provide strongincentives for firms to offer old-age insurance in a least.cost way andto cater to the preferences of their customers.

By contrast, no such institutional arrangements exist in the publicsector. There are no profits, by definition, in the public sector. Agrowing body ofliterature on the economics of bureaucracyU explains,however, that in the absence ofthe profit incentive, utility-maximizingpublic bureaucrats will pursue the objective of increasing their con-sumption of perquisites such as stalL travel allowances, on-the-jobleisure, and so on. And all of these items are more likely to he

“See Henry Mannc, ‘‘Mergers and the Market for Corporate Control,’’ Journal of

Political flconorny 73 (April 1065): 110—20.“See Ludwig von Mises, Bureaucracy, 2d cd. (Westport, Coon.: Arlington HousePublishers, 1969); Cordon Tuhloek, The Politics of Bureaucracy (Washington, D.C.:Public Affairs Press, 1965); and William Niskanen, Bureaucracy and RepresentatieeCoeernsnent (Chicago: Aldine-Atherton Press, 1971).

448

A CONSTITUTIONALI5T APPROACH

obtained with a larger budget for the bureau. Thus, public-sectorbureaucrats such as those at the SSA are likely to act so as to maximizediscretionary revenues—the excess revenues beyond the cost of pro-viding old-age insurance—and to have a strong preference for on-the-job leisure, since the price of leisure is lower in the public sectorthan in the private sector. Consequently, the SSA has little incentiveto make changes that will better serve the needs of its “customers.”Such changes would be time consuming and costly for the SSA whereasthe benefits, in terms of the probability of achievinga larger budget,would be very small. There is little, if anything, the SSA can gain byimproving service to the taxpayers.

This bureaucratic attitude explains why the overall quality ofgovernment-provided services has the poor reputation it does.. TheSSA bureaucrats can more profitably spend their time (from theirperspective) convincing the Congress and the public (through pub-lications and advertisements) that government old-age insurance pro-vides benefits far greater than what it actually provides, so as to maketheir own positions (and budget) more secure. These bureaucrats areamong the major beneficiaries of the Social Security monopoly. Unlikeprivate monopolists, however, they not only charge a monopoly pricebut also have the power to force consumers to pay it. Governmenthas often been referred to as the monopolist par excellence, and theSSA lives up to that image.

In addition to solving the problems of bureaucratic incentives andmonopoly power, a private system would be a more effective way ofpermitting consumers toarticulate their diverse demands for old-ageinsurance. Each individual could purchase different amounts andtypes of insurance, according to his preferences. By contrast, thecurrent system entails a tremendous welfare loss, since it imposesone set of benefit provisions on everyone. The inefficiency of thissystem is readily apparent. Single workers must pay for survivorsinsurance that they do not need—if an unmarried worker (with nochildren) dies, nothing is paid in his name, despite years of contri-butions; single people must buy the same amount of insurance asmarried people; people without children pay the same as those withchildren; those in low-risk occupations contribute as much as thosewho work in high-risk jobs, and so on. The list is almost endless.

A further problem is that there is no relation between (tax) pricespaid and benefits received. Unlike the private sector, where consum-ers could trade off different types of insurance coverage and othergoods depending on their incomes, preferences, and relative prices,the “price” ofSocial Security is determined by current benefit levels,and no tradeoffs are allowed. Furthermore, the true price of Social

449

CATO JOURNAL

Security is well hidden from the average taxpayer, who is not likelyto know that he himself pays for his “employer’s contribution” in theform of lowerwages. Not to mention the fact that the true opportunitycost would include the (private) return he could have earned undera private system and the effects of reduced capital accumulation andeconomic growth.

If individuals prefer a change in the types of benefits provided bythe Social Security system, they must bear the costs of becominginformed about the current system and must discoverwhat politiciansare promising to do about it. Finally, they must hear the cost ofbecoming part (~fan organized coalition powerful enough to influencelegislation. These transactions costs are inordinately high comparedto those in the private market, which is far more conducive to makingmarginal adjustments.

Government provision of old-age insurance will also necessarilyresult in an inequitable distribution of benefits, since the distributionwill be shaped according to the preferences of the groups with themost political clout. Those who are not well organized and wellfinanced will always be the net losers. As Peter Ferrara has shown,this group includes women, blacks, the poor, the young, and, ironi-cally, many of the elderly, who would be better offwith the right toinvest their finds as they see fit. By inflicting costs on these groups,the Social Security system may very well have sown the seeds of itsown demise, for beyond some point the marginal benefits to theseand other groups of securing truly effective reform via privatizationwill outweigh the marginal transactions costs. Perhaps then politi.cians will finally begin to feel the heat. And as the late Senator EverettDirksen once said, “When politicians begin to feel the heat, theybegin to see the light.”

IV. The Role of Public AdvertisingOne aspect of Social Security that has generated much criticism is

the nse of allegedly misleading advertising by the SSA. Advei’tisingplays a prominent role in both the private and public sectors, althoughthe net effects are quite different in the two settings. In the privatesector, insurance companies advertise primarily to provide infor-mation regarding product quality and prices, since consumers typi-cally have very limited knowledge of the alternative products avail-able to them. Furthermore, the firms with the most reliable productsare likely to advertise most heavily, for they have the most to gainfrom repeat sales.’1 There is also considerable evidence that adver-

‘“Sec Yale l3rozen, ‘‘Advertising, Competition, and the Consumer,’’ IntercollegiateReview S (Summer 1973): 235—42.

450

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH

tising makes the economy more competitive by facilitating compar-ison shopping.’3 Economic research has revealed, in fact, that legis-lative restrictions on advertising tend to lessen competitive pres-sures and to raise prices. And, although much fraudulent or misleadingadvertising exists, as long as the consumer has the option of compar-ingand contrasting competing claims of advertisers he is unlikely tobe continually misled or “exploited.” Market competition protectsthe consumer from fi-audulent advertising, although there are alsolegal restrictions on such behavior. In fact, private advertising is oneof the most heavily regulated economic activities.

Is it also true that government advertising by agencies such as theSSA is on a parwith private advertising? That is, does it aim to informcitizens of available alternatives? The answer to this question is anunequivocal no, since the consumers of Social Security have nomarket choice. Like most other services provided by government,old-age insurance is monopolized: The consumer has no choicebetween the SSA and a private insurance company. He must continueto pay Social Security taxes regardless of which alternative he mayprefer.

Since the SSA does spend large sums on advertising, the questionbecomes: Are politicians and bureaucrats held legally liable for theirpromises, as they insist their private-sector counterparts should be?As Richard E. Wagner pointed out in a most original analysis of therole of public advertising:

Politicians cannot be held liable for their promises. If a hot dogmanufacturer’s all-meatproduct turns out tobe 30 percent chickenand bread crumbs, he will most likely encounter difficulty with thegovernment, even if consumers buy the product. But when thegovernment’s eo,uparahle product turns out to he 60 percent balo-ney, no regulatory agency will take action.’4

This, of course, is not to suggest that more regulation is needed.The point is that politicians and bureaucrats are not in fact held liableforfalse advertising, and the SSAis amongthe most serious offenders.In a now-famous statement from a booklet published by the SSA weare told:

The basic idea of Social Security is a simple one: during workingyears employees, their employers, and self-employed people pay

‘3See Lee llcnham, “The Effect of Advertising on the Price of Eyeglasscs,” Journal of

Law and Economics 15 (October 1972): 337—52; and Yale Brozcn, Concentration,Mergers, and Public Policy (New York: Macmillan, 1982).~ F. Wagner, ‘‘Advnrtising and the Public Econo]ny: Some Preliminary Rumi-

nations,” in David Tucrck, ed,, The Political Economy of Adcertlslng (Washington,D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 1976), pp. 81—100.

45’

CAm JOURNAL

Social Security contributions into special trust funds. When earn-ings stoporare reduced hecat,setbe workerreti,’es, dies, orbecomesdisabled, monthly cashbenefits are paid to replace part of the earn-ings his {hmily has lost.’”

Similar statements are made through government campaigns, thepress, and on radio and television. As Milton Friedman has said,however, it would be hard to pack a greater number of false andmisleading statements into a single paragraph. Individuals do notpay Social Security “contributions.” Contributions are voluntary;Social Security taxes are not—and failure to pay them will result infines, imprisonment, or both. Furthermore, employers do not pay‘‘their share’’ of Social Security taxes; the burden of taxation is ulti—inately shifted to the wage earneriC The above paragraph also givesone the impression that the “special trust funds” are actually sumsof money that are saved and invested much like private pensionfunds, rather than being immediately paid out in benefits. Finally,one also gets the impression that one’s future benefits will be paidfrom the “trust funds” and that such henefits are guaranteed. Inreality, the only guarantee is the willingness and ability of futuregenerations to pay Social Security taxes.

Apparently, the purpose of such advertising is to mislead the publicinto believing that Social Security is in fact equivalent to privateinsurance. Perhaps that is why we are told that Social Security cardsare “the symbol of your insurance policy under the federal SocialSecurity Law.”7 Because of the absence of market constraints, andbecause politicians and bureaucrats themselves are “responsible”for enforcing laws or standards regarding false and misleading adver-tising by government, such activities can be expected to continuethroughout the SSA in particular and the government generally.

Another effect of misleading advertising by the SSA stems fromthe fact that Social Security benefits, like the benefits of most gov-ernmental services, fall into the category of goods economists call“credence services.”8 These are services whose quality is difficulttojudge. Many private services, e.g., car repair, fall into this category,and individuals can be induced to pay more for the service if theyare unsure about the quality. The unsuspecting motorist who thinks

31J5 Departnscnt of Health, Education, and Welfare, Your Social Security (Washing-

ton, D.C., Jo,se 1976), as cited in Fcrrara, p. 66.

‘°lhid.‘7Warrcr, Shore, Social Security: The Fraud in Your Future (New Yom’k: Macmillan,

1975), p. 21.S~ichae I Darbya,,d Edi Karn i, ‘‘Free Competition antI the Optimal A,nount oh’ Fraud,’’

Journal of Low and Eco,,oomics 16 (April 1973): 67—88.

452

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH

that all he needs is an oil change has more than once been counseledinto an engine overhaul, although competitive pressures make thisbehavior costly to the station owner and will therefore limit it. Onewould expect this type offraudulent behavior to be even more wide-spread in the public sector, however, because of the difficulty ofevaluating services and the absence of market alternatives.

In light of all this, just what is the function of public advertising aspracticed by the SSAP Richard Wagner seems to have it right:

[Tihe principal function of public advertising would seem lobe topromote acquiescence about the prevailing public policies. Thepurpose ofpnblic advertising would he to reassnre citizens that thefact that their public goods are composed of 60 percent baloneyindicates good performance.’”

Thus, while the Social Security system impairs individual wealthand freedom and exerts a strong negative influence on the economy,the role of political advertising is to draw the public’s attention awayfrom these realities, so as to enhance the prospects for further growthof the Social Security bureaucracy. Such advertising hides the wel-fare aspects of the program. By emphasizing (contrary to fact) thatSocial Security is like an insurance program and that Social Securitytaxes are like insurance premiums, the SSA obscures the trite costsof the program. This increases the political acceptability of the cur-rent program and provides more security not for the elderly, but forthe Social Security bureaucracy.

V. The Provision of Old-Age Insurance: A Case ofMarket Failure?

There have been nume,-ous rationales advanced for the govern-mental provision of old-age insurance to the exclusion of privateprovision, including the “forced savings” argument, welfare andredistributionist rationales, the alleged superiority of a pay-as-you-go system that must be governmentally provided, and the desirabilityof intergenerational transfers. Allof these rationales have beenwidelydiscussed elsewhere, butyet another is of particular relevance to theprivatization issue and will therefore be dealt with here. Namely,the argument has been made that government provision of old-ageinsurance is necessary because of market imperfections that wouldmake private-sector alternatives unattractive or unavailable. This isthe classic “market failure” rationale for government intervention.One alleged market inefficiency stems from the fact that those who

‘“Wagner, p. 97.

453

CATO JOURNAL

anticipate a long life may purchase annuities heavily, which willincrease the rates charged these individuals and toothers. The “aver-age” person may therefore be treated “unfairly” or be priced out ofthe market and will be left without the protection provided him bySocial Security. Thus it is alleged that an “adverse selection” proh-lent exists. However, actuarial rates are based on characteristics ofgroups of purchasers, not on particular individuals. Those who areexpected to live longer (i.e., women) can expect to be charged higherrates than those with lower expected life spans. Prohibiting sucharrangements by government mandate, however, would cause whatone might call a government-induced market “failure.”””

Even if private markets would not emerge for certain groups ofindividuals (which is mere conjecture), one cannot argue for com-pulsory governmental provision on the grounds of economic effi-ciency. For in order for any change to be economically efficient, itmust make someone better off without making anyone worse off.That is why voluntary trade is efficient, but it also explains whygovernmental provision of old-age insurance could never be, for thatwould require unanimous consent. In light of the fact that privatealternatives would yield several times the return to Social Security,unanimous agreement to maintain the current system would beimpossible. The case forprohibiting privatization can only be basedon coercion, not efficiency, as conventionally defined.

A second “market failure” argument is based on the idea that sinceindividuals do not have perfect inforniation about market alterna-tives, and since infbrmation is costly, government provision is needed.Information is a public good, so it is said, so that the market “fails”in this respect to provide the optimum quantity. This particular lineof reasoning commits what Harold Demsetz called the “nirvana fal-lacy”: If one compares a world of perfection with the real world, thereal world will invariably turn out to be imperfect or inefficient.2’ Infact, the market process best facilitates the use of knowledge insociety.22 No group of governmental planners at the Social SecurityAdmirustration could ever make efficient use of all the constantly

““As a similar phenomenon, a group ni wome,, arc currently suing their insurancecompany for charging them higher health—insurance rates than menwith similar medicalhistories because of the fact that women live, or’ average, about 11) years longer than,ncn. If this practice is ruled illegal, insurance companies will he apt to offer less,nedicah insurancu to wonrc,, in the future.“‘Harold Dc,osetz, “Inlor,nation and Efficiency: Another Viewpoint,” Journal ofLowend Economics 12 (April 1969): 1—22,“‘Fricdrich A. 1-tayek, ‘The Usc of Knowledge in Society,” American EconomicReview35 (September 1945): 519—30.

454

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH

changing information that exists in the minds of consumers. Onlyindividuals themselves can make such decisions, and the privatemarket is the only known mechanism that can facilitate this process.Once individuals decided what the “appropriate” retirement age is,when to start buying old-age insurance, etc., private flims wouldmeet the demand. Increased demand for certain types of policieswould be reflected in higher relative prices, which would induce agreater supply.

By contrast, given that personal preferences vary widely, the uni-form provision of one kind of old-age insurance by the governmentwould satisfy the preferences of relatively few. It is the governmentthat is a mjor source of inefficiency in the use of information. Gov-ernmental provision, by definition, cannot accommodate the diver-sity of preferences that exists in the world, More important, govern-mental provision totally subverts the role of the price system inconveying the relevant information. It simply substitutes the pref-erences of bureaucrats for those of consumers, as conveyed by thepricesystent. When one judges the efficiency ofthe private insurancemarket by a benchmark of omniscience, one is quite naturally led tothe conclusion that the market “fails.” But from the standpoint ofreality, it is well known that the private market is much more accom-modating to divei-sity of preferences than the bureaucracy is.

In sum, it appears that the “market failure” arguments in favor ofcompulsory governmental provision of old-age insurance rest on veryweak ground. They are, however, rather typical products of an entireindustry that has evolved, wherein welfare economists concoct anever-increasing volume of excuses for governmental coercion to pro-mote ends with which they personally agree. It appears that sucharguments are nothing but attempts to ease the consciences of thosewho make them.~”

A radical departure from orthodox welfare economics, developedby Ken Shepsle,”4 provides what I believe to be a more accurateexplanation of why the insurance component of Social Security isnationalized. While much has been made of the polar distinctionbetween public and private goods and problems of externalities andother “market failures” in discussions of the “appropriate” role ofgovernment in the economy, Shepsle notes that all goods are mixes

“‘For an elaboration of this view, see T. Nicolaos Tideman, “Toward a Restructuringof Normative Economics,” working paper, Department of Economics, Virginia Poly-technic Institute, 1983.““Kenneth Shcpsle, ‘‘The Private Use of Public Interest,’’ mimeographed (Center forthe Study ofAmerican Business, Washiug’to,, University-St. Louis, 1978).

455

CATO JOURNAL

ofpuhlicness and privateness, and most processes of production andconsumption generate externalities. But the governmental responseto these problems is generally idiosyncratic: Sonic externalities areregulated, others are not; some goods with attributes of publicnessare provided by government, others are not; and many private goodsare provided by government. In short, welfare economics has littleto do with actual governmental decisions to intervene in privatemarkets. Among the factors that are decisive, according to Shepsle,are the opportunities for coalition building by those who stand tobenefit front the program, the abilities of political entrepreneurs toenact the programs (with which they hope to enhance their terms inoffice), and the ability to extol arguments exaggerating market failureand emphasizing the “need” for intervention.

Although Social Security has recently become somewhat ofa polit-ical albatross, it was, formany years, a political goldmine. (Ofcourse,it is still manipulated to secure votes.) For years the program hasbeen a means of dispensing benefits to current voters at the expenseof future generations, who of course cannot object. From the verystart, the system was used by politicians to advance their politicalinterests. Politicians convinced the public that the system would berun on a fully funded basis, hut that promise was soon broken. Con-gress has voted benefit increases without accompanying tax increasesin nearly every election year,”’ so that the systent is now on the vergeof financial collapse. Allowing privatization would impair the empire-building capacities of politicians; that is why the Greenspan Com.mission did not even consider it.

Special-interest groups have also played an important ,-ole in shap-ing the Social Security systcnt, by lobbying for particularized benefitsand for ideological benefits such as increased welfare spending. Ofcourse, the most important interest group is current beneficiaries,who are arguably the strongest political force in the nation, and whoprovide opposition to any significant proposals for change.

Finally, as with all government programs, those who intend to runthe program are the foremost lobbyists in support of it.”” This was

““Ferrara, p. 253.““A current exam pie of this time—worn tracl ition is the en ,sadc to ,‘evitalize HerbertHoover’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), I recently discussed a paper ofmine on that sr,hject at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Washington, D.C. JudgingFrom the Chamber’s mm,agazir,c and television shows, one gets the impression that it isa hastier, offree-market capitalism. However, at that meeting I bond that many, thoughnot all, of the (Thaniher’s board ,nctubers, alding ‘vi th several lormer hoream,crats inattcndaocc, were stan sch advocates of more cm: nt,’al ized economic planning ‘‘if or,lydone cm,r,’cctly.’’ Severalpeople tI,crc elThreddetailed scenarios of how they, as eel,tralplanners ~vo,,Id decide which industries shnulrl s~lrvivethrough government sub si—dization and which shoi ,i cI , ,ot.

456

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH

certainly true at the system’s inception, and few would dispute thefact that the SSA bureaucracy spends much of its time and effortexaggerating the “necessity” of maintaining the status quo (but witha bigger budget) and discouraging privatization.

In summary, the market-failure arguments in support of govern-mental provision of the insurance element of Social Security do notstand up to close scrutiny. It is doubtful that a problem of adverseselection would be ofany consequence under privatization, and evenif itwere, one could not argue for mandatory governmental provisionon efficiency grounds, for efficiency requires unanimous consent.Nor can one claim that imperfect information is cause for govern-mental intervention, forprivate markets have proven to be far supe-rior to government bureaucracies in the use of knowledge—knowl-edge that can be transmitted only via the price system. The case forcompulsory governmental provision of old-age insurance is based oncoercion, not efficiency or equity. In particular, the main impact ofthe current system is to redistribute wealth, not to provide insurance,and the motivation for this system is, I believe, that the people whobenefit from the transfers want them and are adept at using thepowers of the state to secure them.”7 The net losers are all those whodo not receive particularized benefits but who must neverthelesscontinue to pay taxes and experience the effects of slower economicgrowth.””

VI. Summary and ConclusionsIt does not appear that the Social Security crisis can be dealt with

by manipulating the benefit structure or the tax structure every fiveyears or so. At best, this strategy postpones the day of reckoning andpermits politicians to stand on the brink of disaster, piously claimingthey have saved everyone’s Social Security. As discussed above, afirst step toward effective reform is the complete privatization of theinsurance element of Social Security. Privatization would providebenefits more tailored to individual preferences and a higher returnon investment, and would ‘itimulate private savings, capital accu-mulation, and economic growth.

What are the prospects for real reform? The recent actions of theReagan administration, Congress, and the Creenspan Commission

“7This, in fact, is the primary reason Ion most rcdistrihm,tivc programs ofthe government.

See Gordon Tullock, Economics of Income Redistribution (Boston: Kluwcr-Nijhoff,1983).“m

Fcrrana chap. 6.

457

CATO JOURNAL

convey pessimism. Politics-as-usual has produced yet another short-term remedy for a long-term illness. But I am not pessimistic. Thekey to understanding the nature of the problem is to recognize thata major reason for this and other government failures is that therehas been a change in the constitutional setting. A skirmish in thebattle of ideas, if you will, has been won by those who prefer morecentralized control over the economy and a redistribution of wealthto themselves and to other favored groups. A change in public atti-tutes occurred, beginning in the earlier part of this century, whichallowed politicians to abandon their roles as agents whose primarytask was to protect private property rights and todefend the rights offreedom of exchange and freedom of contract.”°Instead, they becamemore brazen in their attempts to revoke individual rights for politicalgain, and the nationalization of the old-age-insurance industry waspermitted to take place.

Thus, what is necessary for truly effective reform is yet anotherchange in the constitutional setting. The value of limited governmentwas understood by writers such as Thomas Jefferson and JamesMadison, as well as many of their contemporaries. Economic libertiesmust once again be appreciated and accorded the same respect thatcivil liberties seem to be given. This may not be as difficult a task asit might appear at first. As mentioned above, the tremendous costsimposed on individuals in all segments of the population by the old-age insurance monopoly will provide them with incentives to inves-tigate and eventually advocate the privatization alternative.

A number of very distinguished authors have misunderstood orignored this basic point, and some have evendeclared Social Securityto be the most successful government program ever, That may betrue, hut it in no way means that citizens would not be far better offwithout it. Furthermore, it is often claimed that the existing systemis successful because “it has majority approval.” But as FriedrichHayek has noted, representative democracy under majority rule,although it is our only protection against tyranny, does not producewhat the majority wants. Rather it produces what each of the interestgroups making up the majority must concede to the others to get theirsupport for what it wants itself.’0 Covernment policy is largely deter.mined by a series of deals with special interests, and Social Security

““This change in time cm,nstit,,tiooai setting has also led to manyofom,r general economicproblems caused by the government’s monetary annl liscal policies. Sec James M.Buchanams and Richard Wagner, Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of LordKeynes (New York: Acaclcmmac Press, 1977).30

Hayck,Law, Legislotion, and Liberty, vol. 3, p. it.

458

A CONSTITUTIONALIST APPROACH

is no exception. In fact, Hayek further noted, majority rule is a mean-ingful phrase only if used to describe agreement on general rules oflaw, not legislation, because the amount of information necessary tomake truly informed decisions about legislation ~i.e., the effects ofthe Social Security system) is prohibitive. By contrast, individualsdo have a conception of the general direction they would like theirgovernment to go in, and the protection of rights to life, liberty, andproperty is one direction that has wide acceptance. The immediateproblem facing the political economist and other concerned citizensis to bring to the attention of the citizenry the Pact that these rightshave been revoked by the Social Security system and other govern-mental interventions and should be reinstated immediately.

Finally, recent events have hinted at prospects for effective reform,for Congress recently voted to place itself and a large part of thefederal bureaucracy under the umbrella (weh?) ofthe Social Securitysystem. On this matter, the authors ofGato’s Letters said ofpoJiticians;

[Wjhen they make no laws bitt what they themselves and theirposterity insist he subject to; when they can give no money, hutwhat they must pay their share of; when they can do no mischief,hut what must faJJ opon their own heads in common with theircountrymen; their principals may expect then good laws, little mis—chief’, and much fi’ugality”

Tam generally proud of the factthat I do not consider myself to bean economic forecaster, but I would like to offer a political forecast.Soon after the 1984 elections, Congress will either attach an amend-ment to a strip-mining hill that will exclude members of Congressfrom Social Security, start up a “supplemental” retirement programfor themselves (perhaps by altering the campaign finance laws), orseriously consider privatization. In any event, the taxpayer will ben-efit; for if either of the former two options is chosen, Congress itselfwill help to expose the Social Security system for the fraud that it is.

~Goto’s Letters, letter 62 (Jans,ary 20, 1721), p. 128, as cited is, Hayek, Law, Legislation,and Liherti;, vol. 3, p. 9.

459

EXPLAINING SOCIAL SECURITYGROWTH

Rudolph G. Penner

Conservatives have a problem. They dislike big government, espe-cially as it intrudes on individual freedom, and they believe theAmerican public must share their tastes, since those tastes are soreasonable. It becomes hard, therefore, to explain why governmentis so large. Fascinating theories of the role of special-interest groups,bureaucratic behavior, and monopolistic government advertising haveemerged to explain the growth of government. DiLoreuzo employsthese theories to explain how Social Security got so large.

I was once quite enamored of such theories. They represent animportant intellectual achievement; some are quite elegant. Theyalso contain more than a small grain of truth. However, I have morerecently made a profession of studying budget numbers, and unfor-tunately the theories that I used to like do not do a very good job ofexplaining more than a tiny fraction ofwhat is going on. The hypoth-esis that most of the public likes big government and does not caremuch for individual freedom seems more consistent with facts.

Take the theory of special-interest groups. Certainly such groupsexist, and certainly they distoi’t government decisions. They influ-ence spending, regulatory, and tax decisions; and I believe it is fairlyclear that they distort the allocation of resources. It is somewhat moredifficult to know how this affects the level of government spending,but I suspect it is biased upward. The questions, “How big is thebias ?“ and “Howdoes it affect Social Security?” are harder to answer.I find it difficult to apply the theory of special-interest groups toexplain very much of the astounding growth of Social Security, butthat theory might help explain the design of the present benefitstructure.

Cola Journal, vol. 3, no.2 (Fall 1983). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved.The author is resident scholar and director of fiscal policy studies, American Entc,’-

prlse Institote, Washington, D.C. 20036.

461

CA’ro JOURNAL

The problem with applying the theory of special-interest groupsto explain the growth 0f Social Security is as follows, A crucial ele-ment of the theory is that special-interest groups can successfullywork for programs that concentrate sizable benefits on a few individ-uals while diffusing the costs overmany individuals, so that the latterdo not find it worthwhile to get organized in opposition to the pro-gram. But this element of’ the theory obviously does not fit SocialSecurity. The benefits are not concentrated on a very narrow group.Those with a direct financial interest (in the sense that the rate ofreturn to all future payments is very high) include the 36 millionalready benefiting, those nearingbeneficiary status, and the relativeswho would otherwise have to contrihute some suppoi-t.

On the tax side, the costs are certainly not diffused enough thattheyare notburdensome. The program is financed bya highly visible,earmarked tax that has risen so much that a majority of taxpayers paymore in payroll taxes than in income taxes. Not only was there no taxrevolt associated with the large increase in this highly visible andburdensome tax, but most of the public responded to opinion pollssaying that more should be done for the elderly even if it meanthigher tax rates. The Social Security issue was at the forefront of the1982 election, and politicians promising to preserve benefits clearlyprospered at the expense of those who did not. It would be prepos-terous to argue that the taxpayers who were financing the increasedbenefits did not know what was going on. The basic point is that mosttaxpayers seem quite willing to pay, as long as they expect theirfuture benefits to be adequate.

As an aside, I note that the theory of special-interest groups mayexplain why government is too large, but it is hard to use the theoryto explain why government has grown to its present size. What Iwould call programs purely for special-interest groups—programs inagriculture, the merchant marine, import aid, and so on—are takingup a diminishing share of the budget and of Cross National Product,as more popular programs (aimed at much broader groups) crowdthem out. I am sure that we can all think of exceptions, but I thinkthe expansion of programs providingvery concentrated benefits anddiffused costs is the exception rather than the rule. The highly con-centrated grants-in-aid programs are an interesting example. Manyfit the model of special-interest groups quite well, but in relation toGNP these programs were cut significantly in both the Carter andReagan administrations.

Does the theory of bureaucracy help explain the growth of SocialSecurity? DiLorenzo claims that bureaucrats “pursue the objectiveof increasing their consumption of perquisites such as staff, travel

462

COMMENT ON DILOBENZO

allowances, on-the-job leisure and so on.” They may pursue suchthings, but they certainly are not very successful. There is now lessemployment in the federal executive branch than 15 years ago, despitea vast expansion in the level of spending and the number of federalprograms. (Someone will mention outside contracting, but that is notnearly as much fun as having your own staff.) Travel budgets havebeen cut to a level that would be considered ridiculously low inprivate firms with similar responsibilities. I have no evidence con-cerning on-the-job leisure. I suspect that it is high, hut I doubt thatit is growing.

What about monopolistic advertising as an explanation ofthe growthof Social Security? I seriously doubt that people are so naive as tobelieve everything they are told in government advertising aboutSocial Security. If! believed that advertising, I would not have muchconfidence in private markets either. But even if one believes thatthe theory of monopolistic advertising is important, it does not helpexplain why Social Security grows so explosively while other pro-grams, like those of NASA (with its hordes of highly skilled PRpeople) shrink in relation to the size of the economy and the rest ofthe budget.

If the above theories do not explain the growth of Social Security,how then can we explain it? If people like Social Security so much,why do they like it (given all of its faults, so excellently outlined byDiLorenzo)? Why was it invented in the 1930s, and not in the 1890sor the 1920s or the l9SOsP

At this point I become very tentative, although I do believe thatDiLorenzo’s arguments are based on a fundamental misconceptionof what Social Security i,s all about. His paper portrays it as a com-pulsory system that is a substitute for private insurance sold in com-petitive markets. But privately sold insurance was not a major alter-native to Social Security before it was invented, and I doubt thatprivate insurance would be the main means of financing retirementtoday—although I admit that it would play a more important rolethan in the pre-World War II era.

The main technique for financing the elderly before Social Security(‘and indeed, since the beginning oftime) was transfers from childrento their parents. This was not a free-market arrangement. It was atype of social contract arrived at as the result of a collective decision-making process. Some element of compulsion, if only that emanatingfrom social pressures, was involved. In other words, the alternative

‘Thomas J. DiLorcnzo, “A Canstitutiooahist Approach to Social Security Reform,” CataJournal 3 (Fall 1983): 449.

463

CATO JOURNAL

to Social Security has never been and would not now entirely be aprivate insurance market conferring complete freedom of choice.Thealternative would be a system of social relationships that generatedmuch tension between parents and children and contained manyuncertainties, since the children might die before their parents, mightbecome disabled, or might even rebel and violate the social contract.

If one sees government tyranny regarding Social Security not asan alternative to individual freedom and competitive markets but asa more secure alternative to family tyranny, it becomes much easierto understand the popularity of Social Security and its explosivegrowth. Indeed, when I have spoken on radio talk shows, advocatinga slowdown in the growth of benefits, many ofthe angriest calls havecome not from recipients, but from the children of recipients.

But why did the program start in the I930s? Why did the level ofretirement benefits stagnate in the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s?Why did the level of benefits soar in the late 1960s and early 1970sand why was it cut back in relation to income (if ever so slightly) inthe late lYlQs and early 1980s? I do not pretend to have reliableanswers. But one can speculate that the social contract betweenparents and children was frequently violated during the economicduress ofthe 1930s, and that the state moved ij~essentially to enforcethe social contract on a depersonalized basis.

But something else may have been goingon as well. When it comesto explaining how government grows, I find the theories of E. C.West most provocative. Studying the nationalization of elementaryeducation in the United Kingdom in the 19th century, he notes thatit would have been impossible to offer state-financed education toall were it not for the fact that almost everyone was already beingeducated privately by free enterprise or by charitable and religiousorganizations. The marginal resource cost ofuniversal education wassmall because the teachers, books, buildings, and so forth, werealready there. If no one had been educated previously, the adjust-ment costs to the economy would have been enormous.2

It might be interesting to investigate the lifestyle of the elderly inthe 1920s, to find out how they were supported and at what level. Itmay be that Social Security did not yield much of an improvementin the living standards of the elderly in relation to the conditions ofthe 1920s, although the improvement may have been significantcompared to what living standards would otherwise have been inthe 1930s.

2Sec E.G. Wcst, Education and the State (London: The lnstitl1te of Economic Affairs,

1965).

464

COMMENT ON DILORENZO

The main point is to the extent that the system is a substitute forprevious systems, it does not impose an additional resource cost.There is some additional cost because the system becomes com-pletely universal. In return, however, it does provide a great dealmore security. It now even provides protection against inflation—protection that is costly to arrange on private markets or within thefamily.

The bottom line, I believe, is that Social Security is a truly popularprogram. Ordinary people are quite willing to give up individualFreedom in return for more security, in part because they place lessemphasis on freedom than we intellectuals do. But more important,alternative family arrangements are not free of compulsion.

Does that necessarily mean that the system is now perfect andshould not be reformed or constrained? Of course not. Earlier Ibelittled theories of special-interest groups and bureaucratic behav-ior. But there is more than a grain of truth there—benefits may havebeen distorted and the nationalized tax-transfer system may in someways be less efficient than a family’s tax-transfer system.

Is Social Security too large? In its absence, would children supporttheir parentsatcomparable levels?Such questions i’eiy rapidly becomemetaphysical. Social Security has had a profound impact on our soci-ety and (among other things) has probably played a very importantrole in explaining falling birth rates. It is hard to imagine how theworld would appear without this system. But such an exercise ofimagination is unnecessary. Anyone who believes that radical reformsof the Social Security system are possible is already living in animaginary world.

465