37, Contribution ofcardiac to understanding ofthe Wolff ...

Transcript of 37, Contribution ofcardiac to understanding ofthe Wolff ...

Invited articleBritish Heart Journal, 1975, 37, 23I-24I.

Contribution of cardiac pacing to our understandingof the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

Hein J. J. WellensFrom the University Department of Cardiology, Wilhelmina Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

This review discusses the information which can be obtained by cardiac pacing in patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Programmed electrical stimulation when combined with the recording of intra-cardiac electrograms and surface electrocardiograph leads, can be extremely useful in the following areas.

I) Determining the type of the accessory atrioventricular connexions; 2) determining the electrophysiologicalproperties of the accessory atrioventricular pathway; 3) localizing the position of the accessory atrioventricularpathway; 4) determining the mechanisms of any tachycardia; 5) assessing effect of drugs; 6) identifyingpatients likely to be at high risk; and 7) evaluating postoperative conduction.

The introduction of epicardial mapping (Durrer andRoos, I967) and programmed electrical stimulationof the heart (Durrer et al., I967) into clinical cardio-logy has resulted in a better understanding of theWolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome and itstherapy. Our opinions on the value and limitationsof epicardial excitation mapping have recently beenpublished (Wellens et al., 1974a). The purpose ofthe present article is to review information which canbe obtained by programmed electrical stimulationof the heart in patients with the WPW syndromeand to consider its uses. The techniques of pro-grammed electrical stimulation will first be de-scribed and the possible substrates for ventricularpre-excitation will then be reviewed. Thereafter theway in which it is possible to locate the position ofan accessory pathway and determine its electro-physiological properties, how the mechanism oftachycardia can be elucidated, how it is possible tostudy the effect of drugs on pre-excitation and howpatients at high risk may be identified, and finallyhow programmed electrical stimulation may be usedfor postoperative evaluation will be described.

TechniqueProgrammed electrical stimulation of the heart demandsthe use of electrode catheters and a stimulator. Thecatheter, preferably a bipolar one, is inserted, usually bymeans of the Seldinger technique, into either a femoral

or an antecubital vein. The tip of the catheter is posi-tioned, under fluoroscopic control, at the desired intra-cardiac location and connected with the stimulator. Caremust be taken that the stimulator is electrically safe forthe patient (Starmer, Whalen, and McIntosh, I964;Burchell and Sturm, I967) and accurate. It should havethe capabilities of providing the following (Wellens(197I)): I) regular pacing of the heart at different fre-quencies; 2) an extra stimulus at any desired intervalduring regular pacing and following any desired numberof paced beats (the 'single test stimulus' method); and3) the possibility of insertion of a stimulus at any de-sired moment in the cardiac cycle during a spontaneousrhythm.

It is necessary to record a His bundle electrogram(Scherlag et al., I969), an intracavitary right atrial lead,and at least two extremity leads and two praecordialleads. If anatomical localization of the accessory path-way is necessary (e.g. to allow subsequent surgical inter-ruption of the bypass), then either a left atrial endo-cavitary electrogram or a recording from the coronarysinus should also be registered.

I. Anatomical substrates for pre-excitationIn pre-excitation, apart from the usual AV path-way, extra atrioventricular connexions are thoughtto be present. If one starts from the concept that theAV junction can be divided into an AV node (com-posed of the compact node and a zone of transitionalcells), a penetrating part of the AV bundle, abranching part of the AV bundle, and the bundle-branches (Hecht et al., I973; Anderson et al., I975b),

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

232 Hein 7. J. Wellens

Transitional Cells Penetrating Branching& Compact Node Bundle Bundle

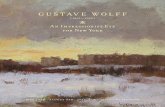

FIG. I Classification and nomenclature of ven-

tricular pre-excitation by the European Study Groupfor Pre-excitation (Anderson et al., 1975a). I) Directconnexion between atrium and ventricle: accessoryatrioventricular pathway; 2) Connexion between theAV node and the ventricle: nodoventricular fibre;3) Connexion between atrium and AV bundle (bundleof His): atriofascicular tract (falls in the group ofAV nodal bypass tracts); 4) Connexion between thepenetrating (left) or the branching part of the AVbundle (right) and the ventricle: fasciculoventricularfibres; 5) Short circuit in the AV node itself (falls inthe group ofAV nodal bypass tracts).

these accessory connexions can be divided (classifi-cation of the European Study Group for Pre-excitation, Anderson et al., 1975a) (Fig. I) into thefollowing. I) Accessory atrioventricular pathwaysforming a direct connexion between atrium andventricle (classical Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW)syndrome); 2) nodoventricular accessory connexions:fibres connecting the AV node with ventricularmyocardium; 3) fasciculoventricular accessory con-nexions: fibres connecting the penetrating part orthe branching part of the AV bundle (bundle ofHis) with ventricular myocardium; 4) AV nodalbypass tracts: either pathways connecting the atriumwith the penetrating part of the AV bundle termedatriofascicular bypass tracts or short circuits withinthe AV node itself.The expected electrocardiographic patterns ac-

companying these connexions would be as follows.A) accessory atrioventricular pathway (classicalWPW): a PR interval of 0.I2 S or less, a delta wave,and a QRS width of O.I2 s or more. B) Nodoven-tricular andfasciculoventricular accessory connexions:a PR interval ofmore than 0.I2 s, a small delta wave,and a QRS width of less than O.I2 s. The length ofthe PR interval and the width of the delta wave andthe QRS depending upon the site of take-off of thefibre. C) AV nodal bypass tract: a PR interval of

O.I2 s or less and a normal QRS complex. Thefinding of accessory AV muscle bundles, previouslycalled Kent bundles, has been reported by severalauthors (see Anderson et al., I975a). Nodoven-tricular and fasciculoventricular fibres have beendescribed anatomically by Mahaim and Winston(I94i), Lev et al. (I966), and Anderson et al.(I974). AV nodal bypass tracts of the atriofascicularvariety have been described by Brechenmacher et al.(I974), while James (I963) described intranodalbypass routes.

In the absence of studies which correlate anato-mical with electrophysiological findings many in-consistencies exist between the anatomical presenceand electrophysiological significance of these acces-sory connexions. Based upon our speculations as tohow connexions in these locations should behaveelectrophysiologically, one would expect the fol-lowing changes during electrical stimulation of thedifferent types of accessory connexions.

A) An accessory atrioventricular pathwayWhen the single test stimulus method is used duringatrial pacing, increase in prematurity of the testpulse results in an increase in area of the ventricleactivated via the bypass. This is because the AVnodal transmission time (the AH interval) increaseswith increasing prematurity of the given atrial pre-mature beat while conduction through the bypass(the atrium to delta interval) stays constant. Aspointed out by Castellanos et al. (I970), during thistype of stimulation the His bundle electrogram,which signals impulse transmission over the AVnode-His pathway characteristically comes progres-sively later after the beginning of ventricular activa-tion via the bypass. The localization of the Hisbundle electrogram relative to the beginning of thedelta wave during sinus rhythm and basic drivingof the atrium will depend upon: a) AV nodal trans-mission time, itself influenced by the rate-depen-dant electrophysiological properties of the AV node;b) the distance between site of impulse formation inthe atrium and atrial end of the bypass tract; c)conduction velocity in the bypass (probably relatedto the thickness of the bypass); and d) the length ofthe bypass. From this it immediately follows that anaccessory atrioventricular pathway (and therefore aWPW syndrome) can exist in the absence of the classi-cal WPW criteria on the standard electrocardiogram.For example the P delta interval may be more thanO.I2 s if the atrial end of the bypass is activated late(localization in the left atrium or because of intra-atrial conduction delay) or the QRS duration may beless than o.i2 s ifpre-excitation ofthe ventricle startslate in relation to ventricular activation through the

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

Contribution of cardiac pacing to our understanding of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome 233

AV node-His axis (Slama, Coumel, and Bouvrain,I973).

B) Nodoventricular and fasciculoventricularaccessory connexionsThe changes in QRS complex configuration aftertest stimuli given with increasing prematurity willdepend upon the level of take-off of the bypass fibresfrom the specific conducting tissue of the AV junc-tion. In contrast to an accessory AV pathway theimpulse on its way from atrium to ventricle has totraverse some AV nodal tissue. Therefore, there willbe some increase in atrium due to delta interval afteratrial test stimuli given with increasing prematurity.The more proximal the point of take-off from theAV node the greater the area of AV nodal delaywhich is short circuited and the greater the amountof pre-excitation. On theoretical grounds a fibretaking off from the AV node at such a location thatthe greater portion of the delay-producing area isbypassed can result in an electrocardiogram indis-tinguishable from that produced by an accessoryAV pathway. They can be differentiated, however,by comparing QRS configuration during right andleft atrial pacing (vide infra).

Accessory connexions taking origin from the AV(bundle of His) can theoretically be recognized bythe presence of short HV intervals (shorter than30 ms). The configuration of the QRS complex willdepend upon the site of ventricular insertion of thepathway and the difference in time between onsetof ventricular excitation over the fasciculoven-tricular fibres and over the normal intraventricularconduction system.

C) AV nodal bypass tractBecause the AV node is short circuited, after atrialtest stimuli given with increasing prematurity theAH interval should characteristically be short.Increase in AV nodal transmission time (AH in-terval) should not occur up to the refractory periodof the bypass. As pointed out by Castellanos et al.(I97I), Mandel, Danzig, and Hayakawa (I97I),Caracta et al. (I973), Bissett et al. (1973), andDenes, Wu, and Rosen (1974) this is a rare finding.Electrical stimulation studies using the single teststimulus method have shown that many patientswith short PR intervals (O.I2 s or less) and normalQRS complexes who were considered to be examplesof an AV nodal bypass tract do in fact show an in-crease in AV nodal transmission time. Caracta et al.(I973) postulated that in some of these patients theAV node might be anatomically small. Mandel et al.(I97I) suggested the possibility of a short circuitwithin the AV node itself. Though one would

theoretically expect the HV interval to be normalin these patients both Mandel et al. (I97i) andDenes et al. (I974) noted them to be shorter than30 ms. This raised the question as to the presenceof other bypass tracts in these patients.

It has been shown by Coumel et al. (I972) thatmore than one bypass tract can exist in the sameheart, a state of affairs which obviously complicatesthe study and treatment of these patients. BothJosephson, Caracta, and Lau (I974) and Spurrell,Krikler, and Sowton (I975) showed that both right-and left-sided pathways could be operative in thesame patient. Furthermore it was suggested bySpurrell et al. (I975) that during tachycardia adifferent accessory pathway was used than thatduring AV conduction in sinus rhythm or atrialpacing.

2. Electrophysiological properties of theaccessory AV pathway

In contrast to the AV node, where the effectiverefractory period (defined as the shortest atrialpremature beat interval followed by conductionthrough the AV node) lengthens with increasingdriving rates, the effective refractory period of thebypass usually shortens with increased driving rates.This is important because it indicates that while theAV node becomes more effective as far as protectingthe ventricle against high atrial rate is concerned, theaccessory pathway might lack this effect of protec-tion against increase in heart rate. As stated earlier,a true AV bypass tract is not characterized bylengthening of the atrium to delta interval followingatrial test stimuli given with increasing prematurity.WhenAV conduction is stressed in patients with theWPW syndrome by pacing the atrium at increasingrates, the differences in pattern of conductionthrough the node and through the accessory path-way can be demonstrated by registering the sequenceof different degrees of AV block in the two path-ways (Table I).

TABLE I Sequence of different degrees of AV blockin accessory atrioventricular pathway and AV node

Accessory pathway AV node

Ist degree block

Mobitz II block Wenckebach type 2nd degree block

2 to I block 2 to i block

Complete block Complete blockr

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

234 Hein . J. Wellens

Examples of Mobitz II block in the accessorypathway and Wenckebach type block in the AVnode have been reported (Roelandt et al., 1973;Wellens and Durrer, I973b).Very rarely Wenckebach type conduction delay

can be observed in the accessory pathway. We haveobserved two such examples in 92 patients withWPW in whom stimulation studies were performed(Wellens and Durrer, 1973b). It is essential toexclude intra-atrial conduction delay, which mightmimic this phenomenon (Castellanos et al., 1972;Narula, Runge, and Samet, I972).By using the single test stimulus method during

ventricular pacing, patterns of ventriculoatrial (VA)conduction can also be studied (Wellens and Durrer,I974a). The following patterns ofVA conduction inthe WPW syndrome can be recognized; i) conduc-tion via the accessory pathway (AP) only; 2) con-duction by both the AP and the His-AV nodal(H-AV) pathway, with either a) the AP having theshortest refractory period, b) the H-AV pathwayhaving the shortest refractory period, or c) withidentical refractory periods for both pathways. Inthe last situation, because of the shorter time in-terval required for passage of the impulse throughthe AP, it will be impossible to distinguish this

pattern from the first; 3) conduction via the H-AVpathway only; 4) absence of VA conduction (boththe AP and the H-AV pathway being blocked).

In our series the most common pattern of VAconduction found was the one characterized by nosignificant change in VA conduction time followingtest stimuli given with increasing prematurity (6iout of 92 patients). This pattern suggests eitherexclusive VA conduction by way of the accessorypathway, conduction through an accessory pathwaywith a shorter refractory period than the H-AVnode pathway, or identical refractory periods in bothpathways. It is of interest to note that 8 of 92 patientswho showed AV conduction over both pathwaysduring atrial pacing had no VA conduction overeither pathway during ventricular pacing! An ex-ample of a progressive increase in VA conductiontime over the AV nodal pathway followed by re-entry over the accessory pathway is shown inFig. 2.

Fig. 3 compares the length of the refractoryperiod of the accessory pathway during ventricularstimulation with that obtained during atrial stimula-tion. In order to make this comparison it is necessaryfirstly that the basic frequency of both ventricularand atrial pacing during which test stimuli were

IVI

His f!i i\j His. X..... XV,~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ K

V6V6

atrium 585 ) 700 )

K or H K H K Kventricle 550 550 320

FIG . 2 VA conduction during regular pacing of the ventricle showing gradual increase in VAconduction time followed by a QRS complex with Wolff-Parkinson-White configuration. Asexplained in the diagram, VA conduction over the His-A V node pathway is assumed to be fol-lowed (at a critical VA interval) by re-excitation of the ventricle over the accessory AVpathway.K= accessory AV pathway, H=His-AV node pathway.

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

Contribution of cardiac pacing to our understanding of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome 235

0

.* .. // 0/

/* ///

200 250 300V1V2 (msec)

FIG. 3 Comparison of the effective refractory periodof the accessory AV pathway as determined by thesingle test stimulus method during atrial and ven-

tricular pacing at identical pacing frequencies. Notethat in Io of the II patients the refractory period inVA. direction was shorter than in AV direction.

applied was the same; and secondly that the refrac-tory7 period of the right atrium and the right ven-tricle was shorter than that of the accessory path-way. As shown in Fig. 3, IO of the ii patients

showed a shorter refractory period of the bypassduring ventricular pacing. The possible explana-tions of this phenomenon are discussed elsewhere(Wellens and Durrer, 1974a).

3. Localization of the accessory AV pathwayRosenbaum et al. (I945) classified the electrocardio-grams of patients with the WPW syndrome accord-ing to the form of the ventricular complex in prae-cordial leads. Type A was characterized by an Rwave as the sole, or by far the largest, deflection inleads Vi, V2, and Ve, and type B an S or QS as thechief QRS deflection in one of leads Vi, V2, andVe. In patients with type A WPW, early activationof the left ventricle has been demonstrated by epi-cardial mapping (Boineau et al., 1973; Wallaceet al., 1974; Wellens et al., 1974a) and ablation ofpre-excitation followed left-sided surgery (Wallaceet al., I974; Wellens et al., I974a). In patients withtype B WPW, early ventricular activation has beenfound on the lateral and posterior aspect of the rightventricle (Durrer and Roos, I967; Burchell et al.,1967; Boineau et al., I973) and the right side of theinterventricular septum (Svenson et al., 1974).One of the problems in trying to correlate theelectrocardiographic pattem with the site of ven-tricular insertion of the bypass is that the electro-cardiogram represents a fusion complex between

I J -11 #&I4.JAV

-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~A11_P,, ,,AVL .RA | RA _ ;

III AVF--,- His H H ls

V1-1 - i Sl. 1 550 14001 155032d

V2 V_ , V5

V3 Vr6 j____R_

Hiszezf HlisS 4400 n,sec;H

I 550 13601 1 550 130d

FIG. 4 Value of programmed electrical stimulation for classification of WPW. The electro-cardiogram on the left shows pre-excitation with a QRS configuration which would have to beclassified as type B WPW according to the criteria of Rosenbaum et al. (1945). During atrialpacing the introduction of test stimuli with increasing prematurity clearly demonstrates, however,that left-sided (type A) WPW was present in this patient.

A1A2(msec)

300-

250-

200-

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

236 Hein . J. Wellens

ventricular excitation over the AV nodal-His path-way and the accessory pathway. When the contribu-tion to ventricular excitation through the accessorypathway is small the ventricular complex may differlittle from normal. This situation frequentlypreventspredictions concerning the most likely site of theventricular insertion of the bypass (Slama et al.,I973; Durrer and Wellens, I974). It is illustrated inFig. 4. During basic driving the demonstrated elec-trocardiogram would be classified as showing WPWtype B. By giving atrial premature beats with increas-ing prematurity, leading to an increasingly largerventricular area being excited overthe accessorypath-way, it becomes clear that type A WPW is present.By using both the single test stimulus method duringatrial pacing and by pacing the atrium at increasingrates, the augmentation of the area of pre-excitationwill facilitate recognition ofthe most likely location ofthe bypass. When atrial pacing is performed close tothe bypass, the pre-excited area will be larger thanduring pacing far away from the bypass (Wellens,Schuilenburg, and Durrer, I97I; Touboul et al.,1972). An example of this situation is given in Fig. 5.Comparison ofthe effect ofright and left atrial pacingon QRS configuration should also be helpful in differ-entiating between an accessory AV pathway and anodoventricular accessory connexion which shortcircuits an important part of the delay producingarea of the AV node. In the former QRS complexconfiguration will differ during right and left atrialpacing at identical pacing rates. In contrast, suchdifferences would not be observed in the latter

situation because an area of AV nodal tissue pre-cedes the accessory connexion.

Recording right and left atrial (either from theleft atrial cavity or from the coronary sinus) activa-tion simultaneously during ventricular pacing toproduce retrograde conduction can give informationon the location of the atrial end of the bypass. Thisshould preferably be combined by recording atrialactivation from the His bundle lead in the vicinityof the AV node. Left atrial activation which pre-cedes actrial activation low on the interatrialseptum and in the right atrium is a strong argumentin favour of a left atrial origin of the bypass (Zipes,Dejoseph, and Rothbaum, I974; Svenson et al.,I974; Wellens and Durrer, I974d).When left and right atrial activation are recorded

during tachycardia simultaneously with low rightatrial activation in the His bundle lead, it is fre-quently possible to determine whether the accessorypathway is incorporated in the tachycardia circuit(Wellens and Durrer, I974d).

4. Mechanisms of tachycardiaAs postulated by Holzmann and Scherf (I932) andWolferth and Wood (I933) the presence oftwo path-ways between atrium and ventricle produces thetheoretical possibility of a circus movement tachy-cardia utilizing AV conduction over one pathwayand VA conduction over the other pathway. A pre-mature beat together with different electrophysio-logical properties of the two pathways are essentialfor the initiation of such a tachycardia. In order for

I_11 _111 - XA

RA

His

VI

V6 v-'

driving RA, BCL 700 msec driving LA, BCL 700 msecFIG. 5 QRS configuration during right and left atrial pacing at identical pacing frequenciesin a patient with left-sidedpre-excitation. Note that ventricular excitation over the accessory AVpathway is much greater during left than during right atrial pacing.

A A

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

Contribution of cardiac pacing to our understanding of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome 237

the tachycardia to be perpetuated, it is necessaryfor the tachycardia pathway length to be longer thanthe product of mean conduction velocity of thecirculating impulse and the mean refractory periodof the tachycardia pathway (Mines, 19I3). Durreret al. (I967) validated these postulated theories byusing programmed electrical stimulation of the heartin patients with the WPW syndrome. They wereable to demonstrate that during atrial pacing acritically timed atrial premature beat was blockedin the accessory pathway and exclusively conductedto the ventricle over the AV node. After activationof the ventricle, re-excitation of the atrium occurredover the accessory pathway. If this movement wasperpetuated, then tachycardia resulted. A similartype of tachycardia could be initiated by an appro-priately timed ventricular premature beat duringventricular pacing. Tachycardias could not only beinitiated by critically timed premature beat butalso terminated by a similar procedure. The ex-planation of this phenomenon was considered to bethe creation of a zone of refractoriness in the tachy-cardia pathway upon which the circulating impulsecollided. The most common type of circus move-ment tachycardia which can be initiated by a pre-mature beat is the one showing AV conduction viatheAV node. Tachycardias with AV conduction overthe accessory pathway are rare (Grolleau et al., I970;Wellens, I97I; Zipes et al., I974; Wellens and

Durrer, I974a). Apart from the single prematurebeat creating refractoriness in one of the two AVpathways, other mechanisms for initiation of tachy-cardia have been identified, such as an atrial(Wellens, I97I) or ventricular echo beat (Fig. 6). Ithas also been shown that in patients with the WPWsyndrome the accessory pathway does not have to beincorporated in the tachycardia circuit but that thearrhythmia can be confined to the atrium (Fig. 7),the AV node (Wellens and Durrer, I974d), or theventricle (Wellens et al., 1974b). Methods ofestablishing the presence or absence of the accessorypathway in the tachycardia circuit have been givenelsewhere (Coumel and Attuel, I974; Wellens andDurrer, I974d). Identification of the location of thetachycardia circuit becomes mandatory if surgicalinterruption is being considered. Knowledge of itslocation is also helpful in selecting the appropriatedrug for treatment of tachycardia (see below).Lastly, its identification is important if treatment ofdrug-resistant tachycardia by chronic electricalstimulation is contemplated. This is because thesuccess of the method is influenced by the proximityof the site of stimulation to the tachycardia circuit(Wellens, I97I).

S. Effect of drugsProgrammed electrical stimulation provides thepossibility of studying directly the effect of drugs

RA___,- A\J AA :A *A;A A .A iAVr H4 H, H

V6,_V6

atrium

vl

ventricle 550

550 590 1 325 1 375 1 340 1 340

O380 350 1 340 1 340 1

FIG. 6 Initiation of tachycardia by a ventricular echo beat during ventricular pacing. Notethat the QRS complex which follows the premature beat given after 245 ms is preceded by a Hisbundle complex at the same HV interval as the QRS complexes, during tachycardia. Thisventricular complex is thought to be the result of longitudinal dissociation in the AV node (seediagram) leading to re-excitation of the ventricle with left aberrant conduction. From this type ofinitiation of tachycardia we cannot conclude whether during tachycardia an accessory AV path-way is used or that perpetuation of re-entry in the AV node is responsible for the tachycardia.

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

238 Heinm . J. Wellens

RA

LA ,s-500 12701 355 330 1 355 355 1

HisH H

LA -rE--~--r'--~-1 360 1 365 1 .5 1 12551 4701 600 1

His N.ta, ,. _H ~H

VI

FIG. 7 Atrial tachycardia in a patient with the WPW syndrome. Top: initiation of tachy-cardia by an atrial premature beat during pacing of the atrial septum. Note that during tachy-cardia high right atrial activation precedes low right atrial activation (in the His bundle lead)and left atrial activation Bottom: Termination of tachycardia by a single atrial premature beat.The sinus beatsfollowing termination of tachycardia show the same sequence of atrial activationas during tachycardia, indicating that the site of origin of the tachycardia is high in the rightatrium. This could be an example of an atrial tachycardia based upon re-entry in the region ofthe sinus node.

on the electrophysiological properties of the twoatrioventricular pathways and on the mechanismsof tachycardia in patients with the WPW syndrome.

For these measurements pacing frequenciesbefore and after drug administration should be thesame. Stimulating and recording electrode cathetersshould also stay in the same intracardiac location.Table 2 lists the effect of different drugs on the

refractory periods of the AV node and the accessorypathway and on the HV interval. Drug treatment ofsymptomatic patients with WPW syndrome shouldbe preceded by: i) identification and treatment ofcongenital or acquired heart disease which mightprovoke or exacerbate an arrhythmia; 2) identifica-tion of the type of arrhythmia present (circus move-ment tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter,

TABLE 2 Effect of drugs on refractory period of accessory pathway and AV nodeand on HV interval

RP accessory pathway RP AV node HV interval

Procainamide + 0 +Quinidine + -"+ +Ajmaline + O +Digitalis + oPhenytoin o + - 0Atropine o 0Propranolol 0 + 0Lignocaine o+- + 0Verapamil - *-O + 0

Abbreviation: RP =refractory period, + = lengthens, o=no effect,-= shortens.Based on data from Mandel et al. (1973), Rosen et al. (1972), Spurrell, Krikler, and Sowton(i974), Wellens and Durrer (I973a, I974b), and Wellens (I975).

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

Contribution of cardiac pacing to our understanding of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome 239

etc.). If a circus movement tachycardia is present,treatment can be divided into a) prophylaxis oftachycardia and b) treatment during tachycardia.Prophylaxis of tachycardia consists of: i) Preventionof the tachycardia-initiating premature beat and 2)reduction of the differences in length of the refrac-tory period of the two AV pathways. Quinidine, pre-ferably given as a long-acting preparation, is stillthe most effective drug for prevention of the pre-mature beat. Digitalis can reduce the differences inlength of the refractory period of the two pathways(Wellens and Durrer, I973a). Drugs like quinidineor procainamide, by increasing the differences inlength of the refractory period of the two pathways,can theoretically widen the range of premature beatintervals during which a tachycardia can be initiated(Wellens and Durrer, 1974b). In our experience,however, if tachycardias could still be initiated bypremature beats following administration of thesedrugs, the zone of premature beat intervals capableof initiating tachycardia was observed to haveshifted to longer premature beat intervals. Since therefractory period and the transmission time of theAV node are not affected, this suggests that pre-mature beats given at intervals shorter than the onesfollowed by tachycardia meet refractory tissue in theaccessory pathway at its ventricular insertion. If acircus movement tachycardia is present the arrhy-thmia will end if the product ofthe mean conductionvelocity of the circulating wave and the mean re-fractory period of the different components of thetachycardia pathway exceeds the length of thetachycardia circuit (Mines, 1913). Most drugs havea twofold action. Thus, quinidine and procainamideprolong the refractory period in part of the tachy-cardia circuit but reduce its conduction velocity.As discussed elsewhere (Wellens, I975), the finaleffect of a drug will depend upon the size and theelectrophysiological properties of the different com-ponents of the tachycardia circuit. If in patients withrecurrent attacks of circus movement tachycardiacombinations of drugs have to be used, we like tocombine a drug with prophylactic value and pro-longing action on the refractory period of theaccessory pathway (e.g. long acting quinidine) witha drug which prolongs the refractory period of theAV node (e.g. propranolol or verapamil). Underthese circumstances it is frequently necessary todetermine whether the accessory pathway is really apart of the tachycardia circuit (Wellens and Durrer,I974d), since a drug which blocks the accessorypathway will immediately end a circus movementtachycardia, but will not interrupt a re-entry tachy-cardia in the AV node.

Procainamide is the most powerful drug as far aslengthening of the refractory period of the accessory

pathway is concerned (Wellens and Durrer, I974b).It is the drug of choice if atrial fibrillation or atrialflutter with high ventricular rates supervenes,unless serious haemodynamic problems call forimmediate cardioversion. Digitalis can be a danger-ous drug in patients with a short refractory periodof their accessory pathway. It cannot be categori-cally stated, however, that the drug is contraindi-cated in WPW syndrome and atrial fibrillation(Wellens and Durrer, I973a). It is our opinion thatinformation on the length of the refractory period ofthe accessory pathway and the changes invoked bydigitalis are required before deciding to use thedrug. An important point which came out of thesedrug studies is the time dependency of the effect ofdrugs. Digitalis exerted its maximal effect 45 min-utes after an intra-atrial administration. In mostpatients the effect of procainamide, quinidine, andajmaline had disappeared one hour after adminis-tration by the same route. The short-lived effect ofsome of these drugs might explain unsatisfactorycontrol of arrhythmias in patients with the WPWsyndrome.

6. Identification of high risk patientsIf an accessory pathway with a short refractoryperiod is present in a patient with the WPW syn-drome, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter can becomea life-threatening arrhythmia. Indeed ventricularfibrillation has been reported following the onset ofatrial fibrillation (Dreifus et al., I97I). We haverecently completed a study during which we com-pared the length of the refractory period of theaccessory pathway (as determined by the single teststimulus method) with the ventricular frequencyduring spontaneous or electrically induced atrialfibrillation (Wellens and Durrer, I974c). A goodcorrelation was found between the length of therefractory period of the accessory pathway and theshortest RR interval and mean ventricular rateduring atrial fibrillation. This indicates that it ispossible to identify those patients with WPW whoare at risk if atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter super-vene. At present we do not institute drug therapy inthe asymptomatic patient with a short refractoryperiod of his accessory pathway firstly because of theuncertainty regarding the natural history of theelectrophysiological properties of the accessorypathway and of the incidence of sudden death inthese patients and secondly because of the high in-cidence of side effects when employing the mostpotent drugs which lengthen the refractory periodof the accessory pathway. We are following thesepatients carefully and intend to study the propertiesof their accessory pathway at regular intervals.

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

240 Heinj. J. Wellens

7. Postoperative evaluationIn selected centres surgical therapy has been suc-cessfully performed in patients with the WPW syn-drome whose tachycardias cannot be controlledby drug therapy. The necessity of identifying thetachycardia pathway before surgical intervention hasalready been discussed. In those patients who havecircus movement tachycardias with the AV node-His bundle pathway incorporated in the circuit,section of the His bundle can result in relief fromtachycardia (Dreifus et al., I968; Edmonds, Ellison,and Crews, I969; Coumel et al., I972; Dunawayet al., I972; Wellens et al., I974a). In these patientssuccessful interruption of the His bundle can bedemonstrated postoperatively not only by theinability to initiate circus movement tachycardia bya premature beat but also by showing that thereare no changes in QRS configuration following atrialpacing at different sites and different frequencies.This is because ventricular excitation occurs onlyby way of the accessory pathway. Interruption ofthe pathway (Cobb et al., i968; Wallace et al., I97I,1974; Fontaine et al., 1972; Wellens et al., I974a)results in complete cure and is mandatory in patientswith a short refractory period of their accessorypathway. After disappearance of pre-excitation, thepatient should be re-evaluated postoperativelybecause, as discussed previously, in some patientsthe accessory pathway operative in AV during sinusrhythm or atrial pacing might not be the one usedduring tachycardia.

ReferencesAnderson, R. H., Becker, A. E., Brechenmacher, C., Davies,

M. J., and Rossi, L. (I975a). Ventricular pre-excitation.A proposed nomenclature for its substrates. EuropeanJournal of Cardiology. In the press.

Anderson, R. H., Becker, A. E., Davies, M. J., and Rossi, L.(1975b). The human atrioventricular junctional area. Amorphologic study of the atrioventricular node. EuropeanJ'ournal of Cardiology. In the press.

Anderson, R. H., Bouton, J., Burrow, C. T., and Smith, A.(I974). Sudden death in infancy: a study of cardiacspecialized tissue. British Medical Journal, 2, I35.

Bissett, J. K., Thompson, A. J., de Soyza, N., and Murphy,M. L. (I973). Atrioventricular conduction in patientswithshort PR intervals and normal QRS complexes. BritishHeart_Journal, 35, I23.

Boineau, J. P., Moore, E. N., Spear, J. F., and Sealy, W. C.(I973). Basis of cinical-ECG variations in right and leftventricular pre-excitation: a unitary concept of W.P.W.In Cardiac Arrhythmias, p. 421. Ed. by L. S. Dreifus andW. C. Likoff. Grune and Stratton, New York.

Brechenmacher, C., Laham, J., Iris, L. Gerbaux, A., andLenegre, J. (I974). Etude histologique des voies anormalesde conduction dans un syndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White et dans un syndrome de Lown-Ganong-Levine.Archives des Maladies du Cceur et des Vaisseaux, 67, 507.

Burchell, H. B., Frye, R. L., Anderson, M. W., and McGoon,D. C. (I967). Atrioventricular and ventriculoatrial excita-

tion in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (type B). Tem-porary ablation at surgery. Circulation, 36, 663.

Burchell, H. B., and Sturm, R. E. (I967). Electroshockhazards. Circulation, 35, 227.

Caracta, A. R., Damato, A. N., Gallagher, J. J., Josephson,M. E., Varghese, P. J., Lau, S. H., and Westura, E. E.(I973). Electrophysiological studies in the syndrome shortP-R interval, normal QRS complex. American journal ofCardiology, 31, 245.

Castellanos, A., Jr., Castillo, C. A., Agha, A. S., and Tessler,M. (I97I). His bundle electrograms in patients with shortP-R intervals, narrow QRS complexes, and paroxysmaltachycardias. Circulation, 43, 667.

Castellanos, A., Jr., Chapunoff, E., Castillo, C. A., Maytin,O., and Lemberg, L. (1970). His bundle electrograms intwo cases of Wolff-Parkinson-White (pre-excitation) syn-drome. Circulation, 41, 399.

Castellanos, A., Jr., Iyengar, R., Agha, A. S., and Castillo,C. A. (I972). Wenckebach phenomenon within the atria.British Heart journal, 34, I I2I.

Cobb, F. R., Blumenschien, S. D., Sealy, W. C., Boineau,J. P., Wagner, G. S., and Wallace, A. G. (I968). Successfulsurgical interruption of the bundle of Kent in a patientwith Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation, 38,Ioi8.

Coumel, Ph., and Attuel, P. (I974). Reciprocating tachycardiain overt and latent pre-excitation. European journal ofCardiology, I, 423.

Coumel, Ph., Waynberger, M., Fabiato, A., Slama, R.,Aigueperse, J., and Bouvrain, G. (I972). Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Problems in evaluation of multipleaccessory pathways and surgical therapy. Circulation, 45,I2I6.

Denes, P., Wu, D., and Rosen, K. M. (I974). Demonstrationof dual A-V pathways in a patient with Lown-Ganong-Levine syndrome. Chest, 65, 343.

Dreifus, L. S., Haiat, R., Watanabe, Y., Arriaga, J., andReitman, N. (I97I). Ventricular fibrillation: a possiblemechanism of sudden death in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation, 43, 520.

Dreifus, L. S., Nichols, H., Morse, D., Watanabe, Y., andTruex, R. (I968). Control of recurrent tachycardia ofWolff-Parkinson-White syndrome by surgical ligature ofthe A-V bundle. Circulation, 38, 1030.

Dunaway, M. C., King, S. B., Hatcher, C. R., and Logue,R. B. (1972). Disabling supraventricular tachycardia ofWolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (type A) controlled bysurgical A-V block and a demand pacemaker after epi-cardial mapping studies. Circulation, 45, 522.

Durrer, D., and Roos, J. P. (I967). Epicardial excitation ofthe ventricles in a patient with Wolff-Parkinson-Whitesyndrome (type B). Circulation, 35, I5.

Durrer, D., Schoo, L., Schuilenburg, R. M., and Wellens,H. J. J. (I967). Role of premature beats in the initiationand the termination of supraventricular tachycardia in theWolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation, 36, 644.

Durrer, D., and Wellens, H. J. J. (I974). The Wolff-Parkin-son-White syndrome, anno I973. European Jrournal ofCardiology, I, 347.

Edmonds, J. H., Ellison, R. G., and Crews, T. L. (I969).Surgically induced atrioventricular block as treatment forrecurrent atrial tachycardia in Wolff-Parkinson-Whitesyndrome. Circulation, 39, Suppl. I, I05.

Fontaine, G., Guiraudon, G., Vachon, J., Bernard, J. P.,Potier, J. C., Grosgogeat, G., and Cabrol, C. (I972).Section d'un faisceau de Kent dans un cas de syndrome deWolff-Parkinson-White de type A-B. Archives des Maladiesdu Cceur et des Vaisseaux, 65, 905.

Grolleau, R., Dufoix, R., Puech, P., and Latour, H. (1970).Les tachycardies par rythme r&ciproque dans le syndrome

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from

Contribution of cardiac pacing to our understanding of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome 241

de Wolff-Parkinson-White. Archives des Maladies duCceur et des Vaisseaux, 63, 74.

Hecht, H. H., Kossmann, C. E., Childers, R. W., Langen-dorf, R., Lev, M., Rosen, K. M., Pruitt, R. D., Truex,R. C., Uhley, H. N., and Watt, T. B., Jr. (I973). Atrio-ventricular and intraventricular conduction. Revisednomenclature and concepts. AmericanJ'ournal ofCardiology,31, 232.

Holzmann, M., and Scherf, D. (I932). Uber Electrocardio-gramme mit verkiirzter Vorhof-Kammer-Distanz undpositiven P-Zacken. Zeitschrift fur klinische Medizin, x2I,404.

James, T. N. (I963). The connecting pathways between thesinus node and A-V node and between the right and leftatrium in the human heart. American Heart J3ournal, 66,498.

Josephson, M. E., Caracta, A. R., and Lau, S. H. (I974).Alternating type A and type B Wolff-Parkinson-Whitesyndrome. American Heart_Journal, 87, 363.

Lev, M., Leffler, W. B., Langendorf, R., and Pick, A. (1966).Anatomic findings in a case of ventricular pre-excitation(W.P.W.) terminating in complete atrioventricular block.Circulation, 34, 7I8.

Mahaim, I., and Winston, M. R. (194I). Recherches d'ana-tomie comparee et de pathologie experimentale sur lesconnexions hautes du faisceau de His-Tawara. Cardiologia,5, I89.

Mandel, W. J., Danzig, R., and Hayakawa, H. (I97i). Lown-Ganong-Levine syndrome. A study using His bundleelectrograms. Circulation, 44, 696.

Mandel, W. J., Laks, M., Obayaski, K., and Clifton, J. (I973).Electrophysiologic features of the W.P.W. syndrome:modification by procainamide (abstract). Circulation, 48,Suppl. 4, I95.

Mines, G. R. (I9I3). On dynamic equilibrium in cardiacmuscle. Journal of Physiology, 46, 23.

Narula, 0. S., Runge, M., and Samet, P. (1972). Second-degree Wenckebach type AV block due to block within theatrium. British Heart J7ournal, 34, I127.

Roelandt, J., Schamroth, L., Draulans, J., and Hugenholtz,P. G. (I973). Functional characteristics of the Wolff-Parkinson-White bypass. A study of six patients with Hisbundle electrograms. American HeartJournal, 85, 260.

Rosen, K. M., Barwolf, C., Ehsani, A., and Rahimtoola, S. H.(I972). Effects of lidocaine and propranolol on the normaland anomalous pathways with pre-excitation. AmericanJ7ournal of Cardiology, 30, 80I.

Rosenbaum, F. F., Hecht, H. H., Wilson, F. N., and Johnston,F. D. (I945). Potential variations of the thorax and theesophagus in anomalous atrioventricular excitation(Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome). American HeartJournal, 29, 28I.

Scherlag, B. J., Lau, S. H., Helfant, R. H., Berkowitz, W. D.,Stein, E., and Damato, A. N. (I969). Catheter technique forrecording His bundle activity in man. Circulation, 39, I3.

Slama, R., Coumel, Ph., and Bouvrain, X. (I973). Les syn-dromes de Wolff-Parkinson-White de type A inapparentsou latents en rhythme sinusal. Archives des Maladies duCceur et des Vaisseaux, 66, 639.

Spurrell, R. A. J., Krikler, D. M., and Sowton, E. (I974).Effects of verapamil on electrophysiological properties ofanomalous atrioventricular connection in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. British Heart Journal, 36, 256.

Spurrell, R. A. J., Krikler, D. M., and Sowton, E. (I975).Problems concerning assessment of anatomical site ofaccessory pathway in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.British Heart Journal, 37, 127.

Starmer, C. F., Whalen, R. E., and McIntosh, H. D. (I964).Hazards of electrical shock in cardiology. American Journalof Cardiology, 14, 537.

Svenson, R. H., Gallagher, J. J., Sealy, W. C., and Wallace,A. G. (I974). An electrophysiologic approach to the sur-gical treatment of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome:report of two cases utilizing catheter recording and epi-cardial mapping techniques. Circulation, 49, 799.

Touboul, P., Tessier, Y., Magrina, J., Clement, C., andDelahaye, J. P. (I972). His bundle recording and electricalstimulation of atria in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome type A. British Heart Journal, 34, 623.

Wallace, A. G., Boineau, J. P., Davidson, R. M., and Sealy,W. C. (I97I). Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. A newlook. American Journal of Cardiology, 28, 509.

Wallace, A. G., Sealy, W. C., Gallagher, J. J., Svenson, R. H.,Strauss, H. C., and Kasell, J. (I974). Surgical correctionof anomalous left ventricular pre-excitation: Wolff-Parkinson-White (type A). Circulation, 49, 2o6.

Wellens, H. J. J. (197i). Electrical Stimulation of the Heartin the Study and Treatment of Tachycardias. H. E. StenfertKroese N.V., Leiden.

Wellens, H. J. J. (I974). Effect of drugs on Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and its therapy. In Clinical His BundleElectrography. Ed. by 0. Narula. F. A. Davis, Philadelphia.In the press.

Wellens, H. J. J., and Durrer, D. (I973a). Effect of digitalison atrioventricular conduction and circus-movementtachycardias in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-Whitesyndrome. Circulation. 47, I229.

Wellens, H. J. J., and Durrer, D. (I973b). Combined conduc-tion disturbances in two AV pathways in patients withWolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. European Journal ofCardiology, I, 23.

Wellens, H. J. J., and Durrer, D. (1974a). Patterns of ven-triculo-atrial conduction in the Wolff-Parkinson-Whitesyndrome. Circulation, 49, 22.

Wellens, H. J. J., and Durrer, D. (1974b). Effect of procaine-amide, quinidine and ajmaline on the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation, 50, I14.

Wellens, H. J. J., and Durrer, D. (I974c). Relation betweenrefractory period of the accessory pathway and ventricularfrequency during atrial fibrillation in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (abstract). American J7ournalof Cardiology, 33, I78.

Wellens, H. J. J., and Durrer, D. (1974d). Pathway of tachy-cardia in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation,50, Suppl. 3, 58.,

Wellens, H. J. J., Janse, M. J., van Dam, R., Th., van Capelle,F. J. L., Meijne, N. G., Mellink, H. M., and Durrer, D.(I974a). Epicardial mapping and surgical treatment inWolff-Parkinson-White syndrome type A. American HeartJournal, 86, 69.

Wellens, H. J. J., Lie, K. I., and Durrer, D. (I974b). Furtherobservations on ventricular tachycardia as studied byelectrical stimulation of the heart. Circulation, 49, 647.

Wellens, H. J. J., Schuilenburg, R. M., and Durrer, D. (197I).Electrical stimulation of the heart in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, type A. Circulation, 43, 99.

Wolferth, C. C., and Wood, F. C. (I933). The mechanism ofproduction of short P-R intervals and prolonged QRScomplexes in ptients with presumably undamaged hearts:hypothesis of an accessory pathway of auriculo-ventricularconduction (bundle of Kent). American Heart J'ournal, 8,297.

Zipes, D. P., DeJoseph, R. L., and Rothbaum, D. A. (I974).Unusual properties of accessory pathways. Circulation,49, I200.

Requests for reprints to Professor Hein J. J. Wellens,University Department of Cardiology, WilhelminaGasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

on Novem

ber 30, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.37.3.231 on 1 M

arch 1975. Dow

nloaded from