BOOKSsianmackay.com/files/2016/04/JR-MAGAZINE-VON-RIPPER-118.pdf · 2018-03-19 · Nazis, including...

Transcript of BOOKSsianmackay.com/files/2016/04/JR-MAGAZINE-VON-RIPPER-118.pdf · 2018-03-19 · Nazis, including...

B aron Rudolph von Ripper was a multifaceted bon viveur. Born in 1905, he was famous in his day as

an artist and a soldier. His friends called him Rip. After World War II, he had been forgotten by history.

At the end of the 1990s I was working as a journalist in Palma de Mallorca. I had never heard of von Ripper until a contact offered me a file containing letters and photographs found abandoned at Ca’n Cueg, a villa near Pollensa in north-west Mallorca. European visitors or exiles to the Spanish island were the subject of my research. Georges Sand, Frederic Chopin, and Austrian Archduke Louis Salvador were names on my list and my contact knew I was on the lookout for others.

The file was stuffed with letters in English and an old German script, mysterious and flimsy on airmail paper, and photographs that spanned decades: military men from other epochs, women wearing dirndls in the Alps, glamorous parties suggesting Hollywood movies of the 1950s. Who were these people?

My informant knew only that the file had belonged to the intriguingly named

Baron Rudolph von Ripper. She had been commissioned by a Scottish artist to rent a villa for a summer art school and, when she viewed Ca’n Cueg (The House of the Frogs), its spacious, light interior struck her as fit for purpose – after certain renovations. The neglected swimming pool was covered with green algae, and when she opened the door to the changing pavilion she was astonished to see dinner suits and evening gowns hanging inside, mildewed and frayed with age. She had entered a time warp. As if in a dream, she followed the trajectory of a large spider running across a bench beneath which was a large blue file.

When the estate agent arranged to bin the contents of the pavilion, sensing that the file might be important, my contact resolved to salvage it. As I would discover, the file, untouched for almost half a century, was extremely important.

Its contents related to the life of von Ripper, an Austrian aristocrat, who had been a youthful witness to World War I

and suffered torture and imprisonment as a ‘degenerate artist’ during the Nazi era. “I hate tyranny even more than war,” he wrote and he enlisted in a fight against it that never ended, even with his death. His mission was to expose, through his art and active resistance, the vulgarities and brutalities of the new ruling classes in fascist countries.

He actively engaged in the tragic dramas of his lifetime that spanned both

world wars. He fought with the French Foreign Legion and in the Spanish Civil War, and befriended many luminaries of his age including Klaus and Erika Mann, Salvador Dalí, Ernest Hemingway, André Malraux and Benjamin Britten. He became a sharpshooter and highly decorated American

intelligence officer in World War II when he captured ‘Hitler’s favourite general’, Otto Skorzeny, in the Austrian Alps in 1945.

The file had piqued my interest. I set off to discover more on an eight-year detective trail to Germany, Spain and the USA. My wonder at the achievements C

OU

RTES

Y O

F T

HE

RU

DO

LPH

VO

N R

IPPE

R A

RC

HIV

E V

IEN

NA

Guns and art: Rudolph von Ripper’s fight against tyranny

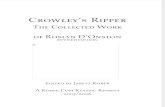

of this legendary soldier-artist reached its zenith in the archive of the New York Public Library when I came face to face with his masterwork, a portfolio of 16 prints titled Écraser l’Infâme (To Crush Tyranny).

Both before and after his incarceration by the Nazis (1933-34), Rip found refuge in Mallorca, his “haven of peace and beauty”, where he created many of the drawings for Écraser l’Infâme. On his first visit, he had been commissioned by the German Resistance to produce anti-fascist, political-satirical drawings. When he returned to Paris several months later, Hitler had become Führer of Germany. The French Resistance had produced a pamphlet portraying Nazi tyranny, the Brown Book (Braunbuch or Livre Brun), cunningly camouflaged as an edition of

a Nazi approved book, Goethe’s Hermann und Dorothea. Rip volunteered to smuggle copies into Berlin and was immediately arrested by Gestapo agents.

At Berlin’s infamous Columbia prison, when he protested that as an Austrian national he was being held illegally, storm troopers responded by fracturing his cranium and throwing him in agony into a grim basement cell. The last thing he remembered before he passed out was the raised arm and clenched fist of one of the thugs reflected in a framed portrait of Hitler hanging on the wall. “I didn’t squeal,” he wrote later. “My heart was filled

with undying hatred for the Third Reich and all it stands for.” The prison doctor transferred him to the state hospital, where the SS repeatedly charged him with “propaganda, treason and espionage”.

In January 1934 there were no celebrations for his 29th birthday; instead he endured further torture and witnessed the suffering of others. A terrifying mock execution left him with permanent angina: “a two-minute slam as bullets and chunks of mortar flew around my head . . . A sudden agonizing spasm rent my heart, and I collapsed. For three days I couldn’t get up and my heart felt violently clenched.”

Transferred to the experimental SS camp KV Oranienburg, Rip was ordered to paint a portrait of Adolf Hitler. Instead he used the time to devise a means of escape with the help of another inmate. A friend of this inmate’s wife would visit Rip and sign in as his fiancée. One day, Rip concealed a message asking for help to the anti-Nazi Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss on a mug that was used by visitors. When his ‘fiancée’ visited she wiped the mug, removed the message and succeeded in getting it to the Austrian legation. A few months later Rip was released with a warning to leave all Nazi-occupied territories immediately.

Traumatised after seven months of torture, he returned to Mallorca to create his blistering riposte to the Nazi regime. “Écraser l’Infâme”, he wrote, “is my answer to the Gestapo commissioner who

warned me to keep my mouth shut” about torture in Nazi camps.

Artists’ eyewitness accounts of brutality in Nazi concentration camps are extremely rare and von Ripper’s forgotten portfolio deserves to stand alongside the art of his contemporaries such as Otto Dix, George Grosz and Käthe Kollwitz. Its title derives from the French philosopher and human rights campaigner Voltaire, who signed his letters ‘Il faut écraser l’infâme’ (Tyranny must be crushed). Rip also admired the radical poet Arthur Rimbaud, whose verses from A Season in Hell preface Écraser L’Infâme. He secured its permanence by publishing 100 copies of each drawing in Paris before he fled the Gestapo in 1938.

He arrived to artistic acclaim in New York. Time magazine illustrated its January 1939 front cover with his print, Hitler Plays the Hymn of Hate, and its editorial noted that von Ripper’s accomplished and emotionally charged portfolio recalled the artistry and anger that fuelled Francisco Goya’s etchings of the Napoleonic War and George Grosz’s images of World War I.

But Rip’s warnings about the impending Holocaust in Europe fell upon deaf American ears. Then Pearl Harbour brought them to their senses. Rip became an American citizen. “Now I can fight and paint,” he wrote when he joined the Allies in the Italian Campaign as a war artist and intelligence officer. “The bravest man I ever saw,” said an American general. “The

kind they write books about,” reported war correspondent Ernest Pyle. So why, then, did history forget this legendary artist hero?

Post-war, Rip settled at Ca’n Cueg and lived the double life

of an artist and a Cold War CIA agent. Mallorca was promoted internationally as a honeymooners’ paradise at the time, but it was also a safe haven for agents and ex-Nazis, including Otto Skorzeny, who had moved into a nearby villa. Rip dreamed of restoring his pre-war artistic reputation, yet cut off from the support of mainstream culture, he gradually slipped out of history. Pursued by his wartime enemies, he died alone in mysterious circumstances at Ca’n Cueg in 1960.

Following the publication of my book about von Ripper’s last year, the battered blue file was delivered to the Rudolph von Ripper Archive in Vienna. n

Von Ripper’s Odyssey: War, Resistance, Art and Love by Sian Mackay, Sancho Press 2017, £9.99. Sian Mackay has lived in Egypt, Spain and the US and is now based in her home town of Edinburgh. Her recently published books have specialised in biography.

“Artists’ eyewitness accounts of brutality in Nazi camps are rare”

“Now I can fight and paint”

A mysterious blue file discovered in an abandoned villa in Mallorca led Sian Mackay to write a book on a little-known Austrian aristocrat called Rudolph von Ripper. Here she uncovers his remarkable story

Clockwise from left: Hitler Plays the Hymn of Hate; Education of the Citizen KV Oranienburg; Defense of Culture KV Oranienburg; Self portrait in a dugout in Italy 1944

BO

OK

S BO

OK

S

42 JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JANUARY 2018 JANUARY 2018 JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK 43

B OOK S