2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

-

Upload

vanessa-ong -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

1/38

1

Employment and PovertyIn

Mae Hong Son Province Thailand:

Burmese Refugees in the Labour Market

Alison [email protected]

Mae Hong Son is one of the poorest of Thailands 76 provinces. The 8 th largest province interms of land area it has the third smallest registered population (at 243, 735 people) apopulation that has been declining due to the provinces limited economic opportunities (UNDP2005:4).1 The main economic sectors in Mae Hong Son Province are agriculture, forestry andtourism. Agriculture accounted for an average of nearly 20 per cent of the provinces outputbetween 1996 and 2002, with major crops including cabbage, paddy, garlic, soya bean and morerecently tomatoes, but the agricultural area accounts for only 3.4 per cent (at official figures) of the provinces total area. Agricultural land is limited as much of the province is mountainous,

with most of it officially classified as forest and national park (UNDP 2005: 4 -5). Data for theproportion of output associated with tourism is not available, though its economic contributionis probably similar to that of the agricultural sector. About 50 per cent of output in the sameperiod was from wholesale and retail trade, with other trading accounting for nearly 27 per centof output (UNDP 2005:4).

In Mae Hong Son Province employment opportunities vary significantly between differentgroups, as the labour market is segmented based on ethnicity and residency status. The localhighlander population is mostly engaged in agricultural production in the more mountainousareas. The proportion of the ethnic minorities within the population (at 63 per cent) is the largestof all the provinces in Thailand. These ethic minority groups are officially classified as membersof different highlander ( hill-tribe ) groups, including Karen, Kayah, Lahu, Lisu and Hmong (UNDP 2005:4). The largest ethnic group in the province is the Thai Yai (or Thai Shan) whodominate agricultural production on the plains (Aguettant 1996:51). Those of Thai ethnicity mostly from Chiang Mai and Bangkok, dominate white-collar employment and the bureaucracy in the province. The Burmese are mostly engaged in irregular employment at the lowest rungsof the labour market in the agricultural, tourism and construction industries. Thai citizens andBurmese migrants rarely do the same types of jobs (at least in the same work place), except fora small number of Thai citizens, mostly over forty who do not own farming land.

About 88 per cent of the population in the province with official registration has Thai citizenship. The other 12 per cent are officially registered, which allows them to legally reside in a particulararea within the province, but they do not have Thai citizenship (UNDP 2005:4). Many of this 12per cent are designated as aliens. This 12 per cent, plus those who are not registered are furthersub-divided into 10 groups based on ethnicity, country of origin and their presumed date of

1 Recently people from Bangkok have been moving to Mae Hong Son for retirement, as the land is cheap, the cost

of living lower and the local environment more conducive. Some of these retirees purchase land employing Burmese to establish market gardens.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

2/38

2

arrival in Thailand.2 The size of this unregistered proportion of the provinces population isunknown.

Nearly all the people from Burma residing in Mae Hong Son Province fled human rights abusesand war in their home country. Many in this group (who arrived prior to 1999) are officially

registered, allowing them to reside within designated areas of the province. However, registrationdoes not grant an entitlement to work, though this restriction has only been enforced since 2000.Many Burmese who fled human rights abuses after 1994 and arrived in Mae Hong Son Provinceentered the refugee camps located on the provinces border with Burma. This excludes those of Shan ethnicity, who are unable to reside in these camps. Many Shan, particularly those who havearrived after 1999 and have not moved to other (more prosperous) provinces are not registered,so reside illegally, usually living in the jungle or on the farms surrounding the remoter villages.Most of those illegally resident in the provinces townships are typically relatives, visiting, trading or on their way to Chiang Mai. Since, around 2000 most people arriving from Burma do not stay in Mae Hong Son Province, but use it as a stepping-stone to work in Chiang Mai and the moreprosperous areas of Thailand.

The following outlines the economic situation of the people originally from Burma living in MaeHong Son Province. It argues that these people have been integral to the provinces economicdevelopment, including the development policies of the Thai State, (not all of which have beensuccessful), providing the labour for the agricultural and forestry sectors and the lower rungs of the tourism and construction industries. Despite this contribution the vast majority, live below the provinces official poverty line. The legal restrictions associated with the official registrationprocess that has allowed some refugee migrants to reside legally in the province and therestrictions associated with work permits have contributed to the very high incidence of poverty amongst this group. The Burmese are also embroiled in many of the informal mechanisms in

Thailand - their situation sometimes determined by personal contacts and the private interests of

Thai citizens. This means that some interactions the Burmese have with the formal legal systemcan depend on the discretion of local officials and Thai citizens able to access this system. 3 Allof this has had mixed results for the Burmese living in the province, and this is evident withregard to identity cards, work permits, land title, education and health care. The paper concludesthat unless the restrictions on those of Burmese descent are removed, by granting Thaicitizenship then the poverty evident within the first and second generation of refugee migrants

will be inherited by their descendants.

In researching this paper interviews were conducted with 50 families of migrant workers in threedistricts of Mae Hong Son Province Mae Hong Son, Pang Mapha, Khun Yuam - at thebeginning of 2003.4 Further interviews were conducted at the beginning of 2004 in the Pai

District of Mae Hong Son Province. The isolated places of residency of recent arrivals notofficially residing in Thailand, coupled with security issues for all concerned, made it impossibleto interview many of these people. Further, for the security of those interviewed they are

2 The 10 groups are 1) Former Kuomintang Soldiers 2) Haw Chinese 3) Free Chinese 4) Displaced Burmese arriving before March 9, 1976 5) Displaced Burmese with permanent residence arriving after March 9, 1976 6)Burmese immigrants (workers) residing at place of employment arriving after March 9, 1976 7) Highland groups(comprised of nine Thai and alien tribes) 8) Highland established communities 9) Illegal alien workers 10) Refugeesliving in border camp (UNDP 2005:4)3 See Christensen & Rabihandana (1994) for more detail on the interaction between the formal and informalstructures in Thailand.4 The survey data utilized in this report (and other interview material) is a small component of a larger researchproject. Central to this was a survey conducted in 2003/04 of 1,200 Burmese migrant families living and working in

Thailand.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

3/38

3

identified by a simple number moniker and basic personal characteristics. Also, the names of the villages and the areas of residence in the townships of the interviewees have not been included.

Poverty in Mae Hong Son ProvinceMae Hong Son is one of the lowest income provinces in Thailand, with an official grossprovincial production in 2002 of 5,358 million baht in 2002 (UNDP 2005:4). The low income of the provinces residents is reflected in the large percentage of people living below the poverty line. The poverty line for the province as set by the National Economic and Social DevelopmentBoard (NESDB) of Thailand for 2002 was 810 baht per person per month (UNDP 2005:16). 5 Based on this definition, 23.18 per cent of the population lived below the poverty line, thoughaccording to official reckoning, poverty in the province had declined dramatically in the previous10 years (from 30.63 per cent).6

Table 1: % of Population below the MHS Poverty Line (810 baht/person/month) Year % Total Population below MHS

Poverty Line% People from Burma below MHS

Poverty Line

1992 30.63 *1994 48.17 *1996 43.06 *2000 27.96 *2002 23.18 *2003 * 78

Source: UNDP (2005)

Based on the definition of poverty set by the NESDB of 810 baht per person per month, it wasfound that 78 per cent of those originally from Burma and their descendants lived in poverty.

This is significantly higher than for the provinces general population (at 23.18 per cent) in 2002.

Table 2 below shows the proportion of Burmese families for different family sizes living below the poverty line. The larger the family size generally the greater percentage of families that arebelow the poverty line. However, even when the migrant worker is alone, more than 30 percent are still below the poverty line, which is still higher than for the general population. Further,the association between family size and the incidence of poverty is not because of a large numberof children, as the average number of children in the families interviewed was only between threeand four (and not all of these are dependents as some are participants in the workforce). Oftenthose in the labour market were supporting not only their children, but elderly relatives,grandchildren, and sometimes orphans and the ill and disabled.

Table 2: Family Size & % of Families Living Below thePoverty Line

5 The national poverty line in 2002 was higher at 922 baht per person per month. (UNDP 2005:16)6 The estimates of the proportion of the population living below the province poverty line show significant variationsuggesting some problem in the gathering of data.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

4/38

4

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Family size

% o f

f a m

i l i e s

Above poverty lineBelow poverty line

Source: BEW Survey 2003/2004

Table 3 below, further highlights this dependency burden of employed migrant workers of allage groups. For example, every migrant worker between the ages of 36-40 who was working atthe time of the survey was supporting nearly eight other people. Even those over 60 who were

working at the time of the survey were supporting more than two people. This high dependency burden partially explains the very high proportion of migrant workers in Mae Hong SonProvince living below the poverty line. The reasons for the dependency burden are discussed

more fully below, but relate to the types of jobs held by migrant workers, most part-time,seasonal and irregular.7 This is exacerbated by the formal and informal structures, whichdiscriminate against migrant workers and their descendants.

Table 3: Relationship between Migrant Workers & Dependents

7 The relationship between underemployment and poverty is highlighted by using an example of a migrant workerfamily in Mae Hong Son Township. The wife in the month surveyed worked 8 days for 3 different employersearning 680 baht. She was employed 3 days at 100 baht per day labouring on a construction site, cleared gardens for3 days at 80 baht per day and spent the other 2 days cleaning rooms in a guesthouse at 70 baht per day. Thehusbands income for the month was 1,000 baht, having worked 10 days at 100 baht per day clearing land. This

family income of 1,680 baht put the three member household below the provinces poverty line, with a per personmonthly income of only 680 baht.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

5/38

5

Dependency ratio (aggregate) by age cohort

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

0.80

0.90

60

Age of respondent

T o t a l

d e p e n

d e n t s

/ t o t a

l w o r

k e r s

Source: BEW Survey 2003/2004

The majority of migrant workers interviewed in Mae Hong Son Province resided in the lessremote areas and were longer-term residents with Thai identity cards. It is very likely that if, alarger number of new-arrivals could have been included in the survey, the proportion of refugeemigrants living below the poverty line would be greater. Before discussing the economicstructure of the province and the formal and informal mechanisms that contribute to this very highincidence of poverty amongst those originally from Burma and their descendants, an overview of

the reasons they left their home country is presented.

Fleeing Burma The interviews conducted reveal that most Burmese migrant workers resident in Mae Hong SonProvince are not economic migrants , but refugees having left Burma due to human rights violationsand civil war - fleeing forced relocation, forced labour, portering and attacks on their villages by the Tatmadaw. 8 The systematic collating of human rights abuses in Burma did not begin until theearly 1990s, thus there is little hitherto direct collated evidence available on Burmese migrant

workers resident in Mae Hong Son Province. 9 An exception is Christensen and Kyaw (2006), who found that the Pa-O from Burma resident in the province fled for similar reasons to thoseinterviewed here. Most of those from Burma living and working in Mae Hong Son Province fledfrom the Karenni and Shan States, with a steady flow of people arriving since the early 1970s. Allthose interviewed and their families at the time (except for one individual), fled either humanrights abuses or are retired, defeated or deserted from one of the ethnic armies that once foughtthe central military regime. The interviewees also reported that those living in the same village ortownship quarter in Thailand had fled for the same reasons.

War & Village Attacks

8 All effort was taken to ascertain and record dates correctly, but inaccuracies can be expected given the length of time that has elapsed since many have arrived in Thailand and the differences between the Buddhist calendars of Burma and Thailand and their difference with the Western calendar.9 While there is very little information about conflict induced displacement prior to the 1990s, the displacement of civilians because o fighting is assumed to have taken place since the start of the war in 1947 (Bamforth et al 2000: p.49)

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

6/38

6

A typical example is that of a Shan woman and her Karen husband, who fled a border village inKarenni in the mid-1980s after their village was burnt down by the Tatmadaw and the residentsforcibly relocated.

We had been attacked about four times by the BSPP [Burma Socialist Program Party] and there was much

fighting in the area before we eventually fled to ThailandWe fled as it became impossible to live in the midst of war. There was the constant problem of hunger and safety... We would have gone anywhere, where there was food and it was safe from the fighting. . We had noidea or even thought about the employment situation in Thailand. We came to Thailand for safety.[Interview 2 Karen Male 54, Hot Set, Karenni:

Arrived 1985]

Another Karenni couple also reported fleeing a border village, after it was attacked by Tatmadaw troops and destroyed.

We came to Thailand in 1980 when the village was attacked by the BSPP [Burma Socialist ProgramParty] , all the houses and the paddy fields were burned. We ran for our life to Thailand and did not look back.

All the people fled from the village into the jungle and then to Thailand.[Interview 3 Karen Woman 50,Karenni: Arrived 1980]

In one village in Mae Hong Son Township the Shan residents had fled from Karenni in the late1970s and early 1980s, also to escape war and its consequences.10

The first group to arrive, in the late 1970s were Shan from Karenni State who ran when the Burmese were fighting the KNPP [Karenni National Progressive Party]. The group left from east of the Salween, as the Burmese were sending mortars from the other side onto the villages so they left down the Pai River to Mae Hong Son Township.[Interview 21 Shan Male 54, Karenni: Arrived 1972]

In another village in Mae Hong Son Province, the Shan, Pa-O and Karen residents also fled war

and human rights abuses in Karenni.11

The first group of arrivals came from Karenni in the mid-70s. The second group arrived in the early 1980s when the Tatmadaw again launched anoperation east of the Salween, though they were forced to retreat. A third group from Karenniarrived in 1990, when the Tatmadaw launched another offensive east of the Salween, though thistime the army stayed in the area. The Pa-O in the village came from the border area betweenKarenni and Shan State in 1990, fleeing the same offensive.12

Those from Shan State and resident in Mae Hong Son Province also fled the civil war, andreported that others residing in their villages in Thailand had fled for similar reasons.

A group from Southern Shan State [ arrived in 1982-1983 ]. At around the same time another group from

Shan State came to live in the village fleeing fighting between SSNLO,13 , SSPP ,

14, PNO

15 , WNO

16 ], Khun Sa and the Burmese.[Interview 21- Shan Male 54, Karenni: Arrived 1972]17

10 The Shan in Karenni State live mostly east of the Salween near the border with Thailand having migrated fromShan State along the Salween. Many of these villages were reported to have been dispersed, with the processbeginning in the early 1970s. There was an earlier movement of Shan from Karenni from where the Salween forksand becomes the Pai River after WW2 due to a major dysentery epidemic in Shan villages. The descendants of theseShan have Thai citizenship.11 Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived 198012 ibid.13 Shan State Nationalities Liberation Organization14 Shan State Progress Party 15 Pa-O National Organization16 Wa National Organization17 These people reside in the same village as the Shan who came from Karenni and discussed earlier by Interview 21.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

7/38

7

In a new quarter of Mae Hong Son Township there are about 500 people, who fled fromSouthern Shan State more recently, with most from the same three areas.

People are always coming into the area.... They are coming as family groups to get away. Many have come

because of fighting in the villages between the SS A,18

the UWSA19

and the Burmese. The villages are being burnt by all of the groups and then taken over... There is always portering and they beat and kick you.The Burmese kill the porters if they are weak or sick. If you join the SSA, you have to stay 3 years. If

you have more than others, then the Burmese run after you, to kill you. You must be poor always. If you have no education or no money to spend, then it is safer.[Interview 19 Shan Woman 31,Ho Pong, Southern Shan State: Arrived 1991]

Forced Labourers & Military Porters Many Burmese from all areas of Karenni and Shan State, now resident in Mae Hong SonProvince, reported fleeing forced labour and portering. Interviewees from Karenni reported thatpeople began fleeing from the mid-1970s, to escape being forced to porter for the Tatmadaw.

Others fled later, for example, a group from Loikaw now living in the same village in Mae Hong Son Province, fled between 1984 and 1986 to escape being military porters. 20 There are many others also from Loikaw District, living elsewhere in the province, who also fled after being forced to porter regularly for the Tatmadaw. 21

My village had to supply porters and forced labour each month. I did the portering for my family since I was 12 years old. I could never sleep well as I was always waiting to be taken. I was once wounded because of fighting between Burmese soldiers and the KNPP [Karenni National Progressive Party] Eventually, I fled intothe jungle and came to Thailand. I ran for about two days to the Salween River. I was then taken by Burmese troops for four days. I escaped and ran to the old KNPP headquarters 22 . I fell down so many times during the night that my body was badly cut and bruised I knew I would die if I stayed a porter. I knew nothing about Thailand. I was just running to save my life.[Interview 4 Burmese Male 39, Loikaw, Karenni:

Arrived 1989] 23

Even those that did not themselves do forced labour or porter for the Tatmadaw lived in villages where the practice was common.

We never did forced labour, but other people in Hot Set were often used as porters by the BSPP [BurmaSocialist Program Party] [Interview 2 Shan Woman 42, Hot Set, Karenni: Arrived 1985]

Another interviewee reported that his elder brother was forced to regularly porter aroundShadaw Township for the Tatmadaw in the earlier 1980s. 24 Many from Shan State also reportedhaving to porter for the Tatmadaw.

When the Khun Sa army was there it was a good time to trade. Later the Burmese took over the area and there were many problems with the soldiers. Even as women, we had to porter for them. Most of the people were afraid; the Burmese had no pity. Sometimes we were kicked; sometimes the soldiers killed us. My father died because he

18 Shan State Army 19 United Wa State Army 20 Interview 25 - Kachin Male 40, Karenni: Arrived 1984 - The interviewee lived in Karenni for many years beforefleeing to Thailand. He had come to Karenni as a Kachin Independence Army (KIA) soldier, when the group wasinvolved in negotiations with the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP).21 Interview 4 - Burmese Male, 39 Karenni: Arrived in Thailand 198922 Huai Plong was the old KNPP headquarters located on the Pai River bordering Thailand23 The interviewee also reported that his father, who had retired from the Burma Railway, was forced to labour onthe same railway in the Loikaw area as himself. His father did not live with the family, as his parents were divorced.24 Interview 38 Shan Male, 35 Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived 1986

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

8/38

8

was a porter. He was old and could not work anymore so they killed him.[Interview 23 Shan Woman48, Eastern Shan State: Arrived 1992]25

Her husband from another area in Shan State fled also in the mid-1980s to escape having toporter for the Tatmadaw. 26

Non-Violent Opposition There are also people, who were involved in non-violent political action in Burma, who now ekeout an existence as migrant workers in Mae Hong Son Province. Some of those engaged innon-violent action have been in the province since the early 1970s. One interviewee was once aprominent member of the Karen community in Loikaw and a wealthy trader, but his prominenceand involvement in the Catholic Church was viewed by the local authorities as synonymous withethnic separatism. In 1970, he came to Thailand for business, but the authorities in Loikaw believed he had fled to become involved in politics. He was warned not to return and has sinceresided in the province. 27

Another, interviewee fled from her home town of Lashio in Shan State, though nearly twodecades later to escape persecution by the local military authorities.

I began teaching the Shan language and cultural traditions in 1965 until 1987, when I had to flee to Thailand.In 1998, I went back to Burma and joined the protests. I was a well known organizer for the NLD in my town of Lashio, during the 1990 elections. I was also involved in campaigning for the NLD in Myitkyina and in

Mandalay. For these reasons, I was well known to the police. I was jailed during the election period. I hid for 2 months after being released, before fleeing into Thailand in 1990.[Interview 4 Shan Woman 48, Lashio,Shan State: Arrived 1990]

Forced Relocation Some of the provinces refugee migrants have come from Demawso Township in Karenni,having fled from the Township, as it was used by the Tatmadaw as a forced relocation site. 28

There were also recent arrivals in the province from those areas in Shan State that the United WaState Army (UWSA) began to occupy in 1999, after moving from the states border with YunnanProvince.29

25 In 1982 Khun Sa and his army, the SUA, were forced to leave their base inside Thailand near Mai Sai by the Thai Army. As a result, in 1984 the SUA took over the area along the border with Mae Hong Son Province, defeating several armed groups including the PNO. The defeat of the PNO by the SUA, though providing economicopportunities for this interviewee (and others), forced others to flee to Mae Hong Son Province. See Interview 9 -Pa-O Male 57, near Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived 198426 The husband and wife in interview 23 left from different parts of Shan State, but both reported being forced toporter for the Tatmadaw. The wife was originally from Eastern Shan State, but moved to engage in trade in theKhun Sa controlled area. The husband in Interview 23 was originally from Pathein in Irrawaddy Division.27 Interview 5 Karen Male 70+, Loikaw, Karenni: Arrived 1970 He had previously been a soldier in the KarenNational Union (KNU) for 5 years between 1948 and 195328 Interview 26 Burmese Male 43, Meiktila Mandalay Division: Arrived 1983 - The interviewee actually stated thatpeople had been coming from Demawso Township since 1984. The wife of this interviewee was from this area inKarenni.29 The Northern UWSA, along with the Tatmadaw, was involved in bringing about the surrender of Khun Sa in1996 to the SPDC. The UWSA then took control of some of the areas previously controlled by Khun Sas army. In1999, the UWSA began to move the civilian population from the Wa hills and the borderline with Yunnan Provinceto Mong Yawn, causing many people to flee to Thailand. See Crampton (2000); Davis (2003); Human Rights Watch

(2003); Shan Herald Agency for News (2000a, 2000b, 2000c); The Lahu National Development Organization(2002:3) estimated that around 4,000 people from the areas occupied by the Wa, after 1999, fled to Thailand.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

9/38

9

There are about 30-40 people from Shan State working in the nearby areas for the Forestry Department. These people left after the second surrender of Khun Sa and the [subsequent] Wa occupation They started to come about 3 years ago and more are still coming.[Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township,Karenni: Arrived 1980]

Ex-Soldiers & Conscripts Some from Burma residing in the province are ex-soldiers or members of the armed oppositiongroups, including the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP), Pa-O National Organization(PNO), Karen National Union (KNU), Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Shan State Army (SSA) and the United Wa State Army (UWSA). Some of the soldiers came after they weredefeated by the Tatmadaw, or another armed group. Other men in Mae Hong Son Province fledfrom Shan State to escape conscription.

The UWSA [United Wa State Army] and the SSA[Shan State Army] are conscripting men & boys for their armies. Some here have run from conscription.[Interview 19 Shan Woman 31, Southern ShanState: Arrived 1991]

Many simply tired of the fighting, internal disputes, corruption and the self-interest of theirrespective leaderships. Others left their respective armies as they had joined as very young menand were tired and hungry.

I was a Wa soldier for about 5 years in the Mae Aw area. I joined when I was about fourteen. My first stepfather was a Wa soldier so I was expected to join the UWSA. I asked to leave so I could take care of my mother who was getting old. I was allowed to leave because I am Karenni. If I were Wa or Shan I would not have had this benefit. I wanted to leave because I was always tired & hungry.[Interview 14

Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived 1980]

Two interviewees, ex-members of the Pa-O National Organization (PNO) were stationed near

Mae Aw in the mid-1970s when the PNO controlled a border gate with Thailand, which it usedfor smuggling and the collection of taxes.30 When the local PNO leader (Khun Ye Naung)decided to surrender in 1977, they were amongst those delivered, without their consent to the

Tatmadaw. 31 One of these interviewees, after being released from a Tatmadaw prison, decided toretire to his home village in the Tha Daung area. Unfortunately, retirement in this village inKaren State entailed being forced to porter for the military. Finally, in the early 1980s his village

was attacked and destroyed by the Tatmadaw, forcing him to flee to Thailand. 32 Another ex-PNO soldier residing in Mae Hong Son Province, who was also handed over to the Tatmadaw inthe same circumstances, returned to the PNO border gate at Mae Aw after being released fromprison.33 He stayed near Mae Aw until Khun Sas Shan United Army (SUA) took over the areain 1984. He, along with about 600 Pa-O, fled the fighting and crossed into Thailand (Christensen

& Kyaw 2006:50).

Recent Arrivals In contrast to the vast majority of people from Burma resident in Mae Hong Son Province, there

were reports that some of the recent arrivals from certain areas in Shan State had come

30 The money yielded was to buy weapons and support the PNO, but it appears that considerable resources weredevoted to enriching the leadership leading to large discrepancies between their standard of living and that of therank and file, fostering discontent, disillusionment and desertion [Interview 8 Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung, KarenState: Arrived 1984].

31 The PNO rank and file soldiers were told they were going to fight the Tatmadaw near Taunggyi in Shan State.32 There are now many reports documenting human rights abuses in the Tha Daung area. For an example see KarenHuman Rights Group 199933 Interview 9 Pa-O Male 57, near Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived 1984

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

10/38

10

specifically seeking employment and to engage in trade. This is because travel in some areas isnow easier, due to the cease-fires the military regime has established with the elite of some armedgroups. However, for those entering Thailand specifically for work Mae Hong Son Province isonly a transit point, on their way to Chiang Mai or other more prosperous areas of Thailand.

Economic Structure & Poverty The main reason for the large proportion of people in Mae Hong Son Province living below thepoverty line is the provinces economic structure, based on low productivity agriculture, forestry and backpacker tourism. Burmese refugee migrants have a much higher incidence of poverty relative to the rest of the population as they hold the low paid jobs within these different sectors.Further, many of the jobs particularly for the low paid in agriculture, forestry and tourism areseasonal and part-time. As such many Burmese migrant workers are underemployed outside of the harvest, planting and peak tourist seasons, exacerbating the low wages and contributing tothe very high incidence of poverty amongst this group. The construction industry is anotherimportant source of employment for the Burmese in the province. Jobs in the constructionindustry are full-time and the wage rate is higher, than most of the jobs available to migrant

workers in other sectors, but the jobs are still irregular.

Agriculture The farms in the province are very small and production is labour intensive, with migrant workers now providing much of the wage labour for this sector. By the early 1980s, as increasedemployment opportunities became available to Thai citizens, the Burmese became the mainstay of the agricultural labour force in Mae Hong Son Province, (and possibly in the other provincesclose to the border with Burma). Further, the interviews revealed that Burmese refugeemigrants have contributed to the development and extension of settled agriculture since the1970s, not just as labourers, but as entrepreneurs and skilled workers. The involvement of Burmese in agricultural development was evident in several of the villages close to the border.Prior to the mid-1970s agriculture in some areas was conducted by a small number of Thai-Shanhouseholds engaged in subsistence farming and Kayah involved in swidden farming. One of thefirst families, Shan from Karenni to settle this border area were skilled irrigators contributing tothe expansion of settled agriculture. This extended family and others from Burma cleared andprepared agricultural land, which was then sold to the local Shan with Thai citizenship.

Burmese refugee migrants in the province have also played a role in the development policies of the Thai State and this is evidenced by the opium eradication program in Mae Hong SonProvince.34 In the areas where opium poppy was cultivated those fleeing Burma were preventedby the locals from settling, until the 1970s when the Border Patrol Police (an elite component of the Thai army) began to oversee the governments program of poppy replacement (Handley 2005:167). The Thai States poppy replacement program required additional and outside labour,due to the shift to other agricultural production, providing employment opportunities for peoplefleeing Burma.35 The Border Patrol Police in some areas of the province allowed the Karenni andBurmese Shan to settle as their labour was required for the success of the states opium poppy eradication program.36

The continual flight of people from Burma into the province has kept agricultural wages low aiding the viability of low productivity and small-scale farming, which dominates the provinces

34 For background on the opium reduction program in Northern Thailand, see Renard 2001.35 Many of the labourers on the poppy farms were apparently drug addicted, so disinclined to supply labour for thenew produce; Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived 1980. 36 Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived 1980.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

11/38

11

agriculture. Many of those employed on farms in the province are Burmese women andteenagers earning as little as 50-60 baht per day.37 Many men from Burma also work asagricultural labourers, though their wage shows greater variability and is generally higher, thanthe wage received by women, earning between 50-100 baht per day. The higher wages aregenerally obtained by men in the remoter areas clearing and preparing new land for agriculture. 38

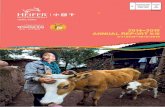

Typical small agricultural plot employing migrant workers (outskirts of MHS Township)

For example, in the District of Pai migrant workers are the mainstay of the agricultural workforce, with the men and woman, earning 70 and 60 baht per day, respectively. A largedeportation conducted in September 2003 created a shortage of labour in this sector, led to lessland being planted than in previous years, highlighting the importance of refugee workers in theprovinces agricultural sector.

A Group of Agricultural Workers in the District of Pai The situation for a group of agricultural labourers in the Pai District is representative of thesituation for other agricultural labourers in the province. The group lived on the land owned by one of their employers, who was also the groups legal employer as designated on their work permits. Their legal employer and his extended family had first call over their labour. When they

were not required by these employers, permission would be granted, allowing them to acceptother part-time employment. However, the group always feared problems with the police, as

work permits restrict the holders capacity to move between employers, even during periods of unemployment.

37 Interview 12 Muslim Male 50, Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived 1980; Interview 26 - In the rainy season the women

and the young workers are not paid daily, but in kind when the rice is harvested.38 Interview 12 Muslim Male 50, Taunggyi Shan State: Arrived 1980; Interview 26 Burmese Male 43, Meiktila,Mandalay Division: Arrived 1983

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

12/38

12

During January and February 2004, very few of the group had obtained any paid employment. At the time of the interviews, the women were thatching new roofs for their home. Any surplus production was to be sold for 3 baht a segment of thatch. Prior to the enhancedenforcement of the legislation in September 2003, the group was employed for about 8 monthsevery year. The enhanced enforcement had made it more difficult to obtain work outside of thatoffered by their official employer, causing a decline in their income. The lower income meantthat most had to borrow money to purchase their work permits, from Thai citizens or othermigrant workers earning higher incomes in the construction industry. 39

Shan agricultural labourers at home (on their employers land) waiting for workIn the areas close to the border

with Burma the wage rate inagriculture is the same for all,regardless of citizenship statusand ethnicity; though only a few older Thai citizens withoutagricultural land work as daily labourers in these areas. Themoney wage in these areas hasnot increased during the last 30years remaining at 50 or 60 bahtper day, depending on gender andthe job.40 The continual flight of people from Burma providing aready supply of labour to theseareas is the principal cause.

Migrant Workers & Subsistence Agriculture Even those Burmese with residency status do not own their own farms, but a smallnumber of migrant workers have access to small plots where food is grown tosupplement meagre monetary incomes. The women are often involved in the collectionof mushrooms, bamboo shoots and wild vegetables in the rainy season and sometimesthe men engage in freshwater fishing.41 In a Burmese Shan village in the District of Pai,the residents cultivated a small garden growing green beans, gourd, coriander andchinboun for consumption. In another village of refugee migrants in the district of Pang Mapha, 3-4 families (out of about 80 families) had enough land to grow food. Those

with this land were the earliest arrivals in the village, with produce again mostly forhome-consumption, as the garden areas were too small to provide a surplus. One garden

was large enough to produce output for sale, but it still only supplied 20 tins of Soyabeans per year, which was sold for 30 baht per tin. The wife also foraged formushrooms, bamboo shoots for 2-3 months of the year, earning around 300 baht eachmonth; enough for cooking oil, salt and feed for the chickens. 42

39 The monthly interest rate on the loan was 5 per cent.40 Interview 25 Kachin Male 40, Karenni: Arrived 198441 Interview 8 - Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung, Karen State: Arrived 1984; Interview 9 Pa-O Male 57, near Taunggyi,Shan State: Arrived 198442 Interview 8 - Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung, Karen State: Arrived 1984

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

13/38

13

Small garden established by a group of about 50 migrant workers, on their employers land in the District of Pai.

Small garden established for private consumption on the edge of their employers agricultural plot on the outskirts of

MHS TownshipTourism

The tourism sector in Mae Hong Son Province centres on budget accommodation for Thaicitizens and the backpacker market for foreign tourists. The investors in tourism are fromBangkok and Southern Thailand, having amassed capital in the beach areas, and are a mix of Siamese and Sino-Thai. Later investment in tourism, particularly in the late 1990s in the PaiDistrict came from Bangkok and Chiang Mai, rather than Southern Thailand. Most employees inthe tourism industry with any responsibility are Siamese-Thai from Bangkok and the tourist areasof Southern Thailand. The Thai Shan occupy the next rung of jobs in the tourism industry,

while those of Burmese descent working in tourism are mostly the young, who have grown upand been educated in Thailand. Older women from Burma are often employed as cleaners in theguesthouses.43 People from Burma have also been used as tourist attractions within the province.For example, one village of Kayan (a.k.a. as longneck Karen) in Mae Hong Son District arerefugees from Karenni in Burma. The local authorities allowed for the establishment of the

village outside of the refugee camps, which is an important tourist attraction for both foreigntourists and Thai citizens.44

In Pai, the enforcement of new regulations restricting employment in the tourism industry to Thai citizens, created a shortage of skilled labour in the industry causing some guest-house andrestaurant owners to continue to employ migrant workers. Many of the Burmese Shan

employed in these small businesses had developed the skills needed in the local industry (including the English language).45 Employers had difficulty replacing these migrant workers, asthe local Thai workers did not have the requisite skills or an interest in working in the localindustry. Many young Thai citizens leave the area to continue their education or go to Chiang Mai and Bangkok seeking work. Many Thai citizens in the area also own their own homes and asmall agricultural plot providing them with alternative sources of livelihood, relieving them of the necessity to engage in low paid, full-time employment. Sometimes the local authorities actindependently to restrict the employment of Burmese migrant workers. For example, a Karen

43 Interview 23 Shan Woman 48, Eastern Shan State: Arrived 199244 There is an entrance fee to the village, which is divided between certain Thai citizens and the political party that

controls most of the refugee camps in the province.45 Even, some restaurants and guesthouses owners received 3 month suspended sentences on 2 year good behaviourbonds for aiding and abetting illegal migration.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

14/38

14

refugee migrant with good English language skills was employed as a tour guide, until the mid-1990s, when the local authorities prevented him from being employed in this capacity as he hadoriginated from Burma. 46

Construction Increased tourism and funding from the central government in Bangkok, as a part of itsNorthern development program, created a small construction boom in the province between1995 and 2003.47 At the beginning of the boom there were many small construction companiesin the province, but these companies had limited capital equipment and machinery, involved only in small labour intensive building projects. In the mid 1990s, when the provinces administrationreceived funding from the central government, the much larger construction companies fromChiang Mai, Lampang and Phitsanulok began to operate in the province, obtaining contracts tobuild the hospital, city hall and extend the airport.

Prior to 1995, much of the unskilled work in the industry was done by refugee migrants fromBurma. In the early 1980s, the daily wage rate was 60 baht for women and 80 baht for men. 48 Coinciding with the local construction boom was an increase in the wage rate to 100 baht perday for men and 80 baht for women. The increase in the wage rate caused some local Thai-Shanand Karen, many of them illiterate to seek employment in the industry. Still, however, most

working in the construction industry in the province doing the low paid work are from Burma. The wage rate for all the ethnic groups are the same for the same job when the skill levels arelow. This is different for workers with trade skills as the Thai citizens earn significantly morethan the Burmese with similar skills.

Hand Dredging for Construction Materials In Mae Hong Son Province some of the materials for construction, notably the sand and gravelhas come from the Pai River. Burmese refugee workers have for the last 25 years, collectedthese materials, usually living on land next to the river owned by their employer. Typically, the

work is performed in pairs, always without the assistance of any equipment, with workers being paid for the number of tins filled. The work predominates in the wet season, as the rains bring the sand and gravel down the river aiding collection, with a pair of workers able to collectbetween 50-100 tins each day. During the dry season, the river is very low and too cold for the

workers to stay in the water for extended periods. 49

46 Interview 1 Karen Male 65, Karenni: Arrived 197647 Interview 46 Shan Male 45, Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived before 199048 It was during this period in the early 1980s that the Holiday Inn and the Court Building in Mae Hong Son

Township were built.49 The women in particular working in the Pai River incurred health problems, including miscarriages due to thecold.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

15/38

15

Tins used to collect sand & gravel from the Pai River Thailand Collecting sand & gravel Myawaddy Burma

Collecting sand & gravel Myawaddy Burma

Collecting sand & gravel Myawaddy Burma (Photos Alison Vicary )

One married couple reported that in the early 1980s they would fill together about 50 tins perday in the wet season.

We had to get the stones out of the water. It was very hard work. Because I had to stand in water all day, I developed asthma and other respiratory problems. The cold from standing in the water all day caused me tomiscarry 3 times during this period. The last time twins died in my womb so I had to have an operation to have them removed.[Interview 6 -Shan Woman 44, Karenni: Arrived 1982]

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

16/38

16

The migrant workers collecting sand and gravel for construction during the 1980s reportedbeing paid one baht per tin. 50 The price twenty years later in 2003 had risen to only two baht pertin. This meant that in 2003 the maximum daily wage possible for each worker collecting sandand gravel in the peak season would be 100 baht.

Forestry The logging industry and trade in teak began with Chinese merchants in Northern Thailand,expanding after 1880 when European-logging companies financed Burmese contractors toobtain licenses from local Thai leaders. The Royal Forestry Department the main governmentbody overseeing forests in Thailand was established in 1886 to lessen disputes betweenEuropean logging companies, caused by the granting of logging leases to different companiesover the same areas (Renard 1994:659). By the 1950s the leases given to foreign firms had beentransferred to Thai companies, but there was considerable logging outside of the lease areas and

violations of other lease conditions (Silock 1970:104-105). In 1968 the Royal Forestry Department granted Thai logging companies thirty year leases to fell timber on the conditionthat replanting occurred, though again enforcement was at best nominal. These concessions wereeventually revoked in 1989, after considerable protest by environmental groups (Delang 2002:489). It was not until this period that the Thai State ceased to view the forests as a sourceof raw materials for development and the Royal Forestry Department began to have anenvironmental function (Christensen & Raibhadana 1994:6). However, the implementation of this new environmental approach has been inconsistent, often determined by competing localinterests and the consequent inconsistent application of the formal system (Christensen &Raibhadana 1994; Kemp 1981).

Despite the emphasis often given to logging as the cause of deforestation, much of the loss of forest cover in the last 70 years is a consequence of government policy, including the promotionof wood exports for foreign exchange, internal migration to promote the development of cashcrops and the construction of dams for electricity and agriculture. 51 Deforestation even in theNorth is related to government policy. This included the perception that the periphery of

Thailand was under-populated, leading to policies to open the frontier and the promotion of settled agriculture (Delang 2002:487-488). Another policy that aided deforestation was theconstruction of roads in the North, and the promotion of settlement in the 1970s to deny areasto the communist insurgency. 52

In 1930, forest covered about 70 per cent of Thailand, but partially because of governmentpolicy forest cover declined during the rest of the century. By 1950 estimates of forest cover haddeclined to 62 per cent, and by 1974 the estimates were much lower at 37 per cent of the country (Delang 2002:494). In 1980, the estimates were only 25 per cent and in 1986 only 15 per cent

(Delang 2002:494). By 2000, the rapid decline had been halted, but only about 13 per cent of Thailand remained covered by forest. However, the proportion of the land under forest cover inNorthern Thailand is significantly higher than the rest of the country. In Mae Hong SonProvince, nearly 90 per cent of land area is officially classified as covered by forest; though actual

50 Interview 6 Shan Woman 44, Karenni: Arrived 1982; Interview 8 Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung Karen State: Arrived 1984; Interview 15 Kayan Male 42, Southern Shan State: Arrived 1987; Interview 21 Shan Male 55,Karenni; Arrived 197251 This is highlighted by a dramatic expansion in rice cultivation across the country from 960,000 hectares in 1855,to around 1.44m hectares in 1905 and by 1950, 5.6m hectares were under cultivation mostly at the expense of forest

cover (Delang 2002:484, 486).52 Burmas military regime adopted similar policies in the early 1990s when it granted logging concessions to Thaicompanies in areas at least partially controlled by armed ethnic groups opposed to military rule.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

17/38

17

forest cover is lower (UNDP 2005:39). 53 Further, the occupation of national forests in Northern Thailand by squatters is much less of a problem than in other areas of Thailand (Christensen &Rabibhadana 1994:653). Despite the rapid and large decline in forest cover in the first half of thecentury, in 1961 the Thai government declared that the state owned nearly 50 per cent of thecountrys land, which was placed under the control of the Royal Forestry Department (Delang

2002:493 & Sato 2000:16). Now the Royal Forestry Department controls 115 million rai of theland in Thailand, but a survey conducted in 1995 found only 75 million rai was under greencover. The rest had been converted to farm land or acquired by squatters (Christensen &Rabibhadana 1994:653).

Logging The Burmese have a history of employment in the forestry industry in Thailand, beginning when the British companies operating in lower Burma extended their operations into Northern Thailand in late 1850-60s. The logging began near Mae Sot in Tak Province, extended to theforests around Mae Sariang in Mae Hong Son Province and then to other areas in Northern

Thailand. Until the 1930s, the teak industry in Northern Thailand employed mostly Burmese,

Mon and Shan. People from Burma again came to be employed in logging in the 1970s, thoughthis time after they had fled civil war and human rights abuses at home. With the introduction of legislation banning logging in areas designated as forest in 1989, the employment of Burmeserefugee migrants in Mae Hong Son Province in this sector again declined, though many continueto be employed by the Royal Forestry Department in their reforestation and forest protectionprograms.

There is still some (mostly small-scale) illegal logging in limited areas of the province. Some of the employees in this industry are refugee migrants from Burma, but logging is controlled by Thaicitizens, including government officials, forestry employees and the police.54 The industry couldnot exist without the cooperation of the local authorities, for reasons including the

transportation and delivery of wood to buyers.55

Refugee migrants from Burma, due to theircircumscribed economic, social and legal status, are unable to sell or buy teak.56 More typically they are the now group that incurs the brunt of the punishment for the involvement of all inillegal logging.57

Sometimes [Burmese] people get arrested by one group of police, fulfilling the orders made by another group of Thai authorities.[Interview 26 Burmese Male 43, Meiktila Mandalay Division: Arrived 1983]

53 However, only ten years earlier the official figure was only around 70 per cent. The UNDP (2005) report on theprovince does not rate the quality of the data highly, so the sudden increase in forest cover over a 10 year periodshould be accepted cautiously. The report states the following, The proportion of forest area in Mae Hong Son Province for the period 1988 to 1998 tended to continuously decrease, going from 72.95% to 69.14%. However, in 2000 the proportion increased up to 90.04% as a result of actions taken from late 1998 onwards. For example, there was the Chalerm Prakiat Reforestation Project by the National Park, Wild Animals and Plants Department and campaigns launched for reforestation in accordance with the Enhancement and Conservation of National Environment Quality Policies and Plans 1997-2016 (UNDP 2005:40).54 The involvement of forestry officials and police is not an uncommon practice and has been documentedelsewhere. See Christensen & Rabibhadana (1994: 652) for an example.55 Interview 8 - Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung, Karen State: Arrived 1984; Interview 9 Pa-O Male 57, near Taunggyi,Shan State: Arrived 1984

56 Interview 8 - Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung Karen State: Arrived 1984; Interview 9 Pa-O Male 57, near Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived 1984; Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township Karenni: Arrived1980; Interview 26 Burmese Male 43, Meiktila Mandalay Division: Arrived 1983;57 The people from Burma involved often face two charges, illegal entry into Thailand and involvement in the illegalteak trade, with the sentences commonly about four years.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

18/38

18

The increased control by the Thai authorities has meant that the living standard of the Burmesein the villages once dependent upon logging has dramatically declined over the last 15 years.

Fifteen years ago, a piece of teak that was 2 yards long, 1 inch thick and 12 inches wide could be sold for 60baht a piece. In one day 2 people could make 20 pieces of teak. Now the price is 100 baht for the same size

plank but now it takes 4 people, 1 day to make 4 pieces. This is because the danger has dramatically increased requiring two look outs along with the workers to cut the trees. Also, we now have to travel much further tocollect the teak.[Interview 9 Pa-O Male 57, Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived 1984]

The wage now for this form of employment depends upon the particular location within theprovince, determined by the extent of enforcement and ease of access to teak forests. In one areathose employed cutting bamboo were paid around 100-120 baht per day, while those cutting teak received about 150 baht per day. 58 In another area the income for logging teak was stillsignificantly higher than other forms of available employment, with workers receiving between200 and 250 baht per day. 59

Charcoal Production In 1990 about 80 per cent of the provinces population used solid fuels, (i.e. wood and charcoalfor cooking and heating), but this had declined to around 65 per cent in 2005 (UNDP 2005:39).

The very high proportion of the population using sold fuel, suggests that most people do nothave access to alternative fuel sources such as gas, explaining the demand for charcoal and wood,sometimes made by refugee workers burning wood logged in the local forests. Charcoalproduction does not typically involve the complicity of the authorities, as it is less profitable,though the sale of charcoal is controlled by Thai citizens. Some refugee migrants from Burma inMae Hong Son Province, particularly when they first arrive engage in charcoal making as thereare few other jobs available and due to the local demand for the product.

When we first arrived in Thailand we were involved in the illegal cutting and burning of trees to make charcoal My wife hated burning wood for coal, because it was very hard physical work and she was so fearful of being caught. The wood coal was sold to local Thais for 4 baht a tinWood burning is dangerous and the output was often stolen by Thai villagers. The charcoal is easy to steal because it has to stay buried for about 10 days. There was nothing we could do as we knew that it was illegal and so were we Early on I was stopped by a forestry official who asked me for the sake of the forest to stop cutting down trees. I felt very sorry, but I had to continue to feed my family.[Interview 2 - Karen Male 54, Karenni: Thailand 1985]

In villages where charcoal making was once an important source of income, the increasedcontrol by the Forestry Department in cooperation with local village heads has meant the activity has diminished considerably, if not ceased altogether.60 In areas where Thai citizens are willing tosell and buy charcoal, illegal production continues.61

I have worked for 6 years burning wood in the jungle for a Thai businessman. Making the wood charcoal is illegal so I cant sell it openly. I sell it to a local Thai for 50 per cent of the sale price for

58 Interview 26 Burmese Male 43, Meiktila, Mandalay Division: Arrived 198359 Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived 1980

60 Interview 12 Muslim Male 50, Taunggyi, Shan State: Arrived 198061 A married couple was forced to relocate by the police after the husband was reported for charcoalproduction. The police did not charge the man, but stole the charcoal and wood for sale. Another time thehusband was arrested for immigration violation after the seller of his charcoal, a Thai citizen called thepolice after a disagreement. His wife threatened the man that she would report him for his involvement in

teak logging. Frightened he paid the 12,000 baht for her husbands release (Interview 4 Shan Woman 48,Lashio, Shan State: Arrived 1990).

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

19/38

19

about 3,000 baht each month. I have to pay other Burmese workers about 1,000 baht to haul the charcoal from the jungle I am not paid when the charcoal is delivered only when it is sold. As sales are unpredictable we have to purchase food on credit at the store owned by the same businessman whobuys the charcoal. The food is more expensive and there is also a 10 per cent interest rate. This means that we never see the money [Interview 4 Burmese Male 39, Loikaw, Karenni: Arrived

1989].

The production and sale of charcoal in Mae Hong Son Province will continue until the localpopulation switches to alternative sources of energy for cooking and heating. This requirespractical policies to increase the usage of gas (or other energy sources), rather than simply devoting increased resources to forest protection.

Royal Projects & Royal Forestry Department Governance King Bhumibol Adulyadejs Royal Projects and interest in rural development began in the 1950sin the grounds of his Hua Hin palace, with his initial focus on fish farming. In the 1960s anexperimental rice farm, a mini-dairy and a forestry project were established at his ChitraladaPalace in Bangkok (Mogg 2005). The King later developed an interest in the supply of water,particularly those associated with farming. He has sponsored numerous associated projects in thepoorer farming areas of the country, including the construction of many dams. 62 This hasbecome an important component of the Kings reputation, and since the late 1950s, when amajor dam in Tak Province was renamed the Bhumibol Dam, all major hydropower projectshave been named after the royal family (Handley 2005:165).63 Before 1980, the Kings projectsnumbered a few hundred being funded by his Chai Pattana Foundation . However, when GeneralPrem Tinsulandonda became Premier in 1980 the scope and size of the royal projects increased

with support from the Thai government and with the implementation of many of the RoyalProjects transferred to the relevant government department (Handley 2005:89-90). 64

The Royal Projects have been presented as an integral component of the countrys ruraldevelopment program and in Mae Hon Son Province these projects have employed many refugee migrants from Burma. For example, about 300 Burmese who arrived in Mae Hong SonProvince in the 1970s were employed on the Royal Projects associated with the Kings Palace(Pang Tong Palace) and the Ruam Thai Dam. About 300 Burmese were employed for two yearson building the Ruam Thai Dam. The building of the dam took two years and when completedthe group continued to be employed on a series of Royal Projects. 65 The wages for thoseemployed on the Royal Projects were higher than for similar jobs as men earned between 66-70baht per day, and the women 60 baht per day. 66 During the same period those working for theRoyal Forestry Department reported wages of only 20-35 baht per day. 67

62 Water projects were implemented with the assistance of EGAT, (which controls hydropower) and the irrigationdepartment.63 The Kings interest in dam building by 1990 had brought him into public conflict with environmental groups andsometimes the locals affected by the projects.64 King Bhumibol began to determine projects based on his private preferences and these projects took precedenceover the other work of the government departments. In addition, a new body was instituted, the Coordinating Committee for Royal Projects with General Prem as the chair. In 1981 the Coordinating Committee for Royal Projects createdthe Royal Projects Development Board inside the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) thegovernment sponsored planning body, signalling the importance of the Royal Projects in official policy.65 The project was supervised by about 10 Thai citizens (Interview 23 Karen Male 54: Arrived 1984).66 Interview 23 Karen Male 54, Southern Shan State: Arrived 1985; Interview 9 Pa-O Male 57, near Taunggyi,

Shan State: Arrived 198467 Interview 8 Pa-O Male 60, Tha Daung, Karen State: Arrived 1984 and Interview 23 Karen Male 54, SouthernShan State: Arrived 1985

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

20/38

20

However, the governance of the projects managed by Royal Forestry Department and someRoyal Projects implemented under its auspices was poor, with numerous reports of the non-payment of wages.68 Workers did not receive any money or much less than the agreed amount,

with their wages debited ostensibly in line with the debts incurred at the canteens and foodstores established specifically for the employees, who often worked in the jungle. One refugee

migrant, reported working on a Royal Project planting Logan trees near Noi Soi for one and half years, with the implementation of the project overseen by the Royal Forestry Department. The workers were not paid only receiving food from the store established specifically for the workerson the project. 69 At a Royal Forestry Department teak planting project at Huai Po Ma, theBurmese workers were also not paid the agreed 40 baht per day, again only receiving food fromthe workers store .70 A Karen refugee migrant employed by the Forestry Department this time inKhun Yuam District in the early 1980s, reported being promised a daily wage of 30 baht (or 900baht per month). He worked for one and half years in the jungle, with others most of whom

were Thai citizens. All had agreed to have their wages deposited in their bank accounts, butdiscovered when they emerged from the jungle that only a nominal amount of money had beendeposited.71

Many refugee migrants form Burma are still employed by the Royal Forestry Department on theprovinces reforestation and forest protection programs at wage rates local Thai citizens areunwilling to accept.72

Most of the men in the area are working on a Royal Project planting trees for the Forestry Department. NoThais work on these projects. Those working for the Forestry Department in the jungle (without any identity card) earn the same as those working for the department who live in the village. The men earn 70 baht and women 60 baht each day They all work 7 days a week.[Interview 14 Karen Man 23, Shadaw

Township, Karenni: Arrived 1980]

Formal Structures, Segmentation & Poverty The economic structure of the province is a major contributor to the high incidence of poverty amongst the Burmese and the general population. However, for Burmese and theirdescendants the economic structure is exacerbated by formal and informal structures that limittheir employment opportunities, relative to those with citizenship. 73 These structures alsosegment the labour market between Burmese migrant workers, such that those illegally residentin Thailand may in the longer term have better employment opportunities than those with Thaiidentity cards. The most significant formal discrimination arises from the restrictions and

68 This form of corruption appears to be ongoing within the Royal Forestry Department as there are still reports of this practice. For example, Delang (2002:496) reports on a group of Shan from Burma employed by the RoyalForestry Department in Chiang Mai Province in 1999. These workers had been promised 75 baht per day, but at thetime of the report had not been paid for 5 months. These workers were also sold food at inflated prices, seemingly debited from their unpaid wages.

69 Interview 23 - Karen Male 54, Southern Shan State: Arrived 198470 Interview 23 The interviewee worked on this project for 6 months, before being hospitalized injured by a rolling log.71 Interview 5 Karen Male 70+, Loikaw, Karenni: Arrived 197072 The author also interviewed people from Burma working for the Royal Forestry Department in SangklaburiProvince.73 These structures may also be important in explaining some of the different labour market outcomes betweenother groups within the province, but this is beyond the scope of the paper. The labour market outcomes forBurmese refugee migrants and the consequent incidence of poverty are no doubt partially explained by their pooreducation and language skills compared with local Thai citizens, though not all these people in the province are

poorly educated. Further, many of those surveyed had Thai language skills (but literacy in the Thai language was lesscommon) being resident in the province for many years.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

21/38

21

conditions attached to the system of identity cards and work permits. Access to legal title overland is associated with citizenship and residency status and this is another important formal factorin creating segmentation, consequently increasing the incidence of poverty. The fourth formal structure of discrimination segmenting the labour market between Thai citizens and Burmeseeven with residency status is the legal limitations on Burmese refugee migrants engaging in

business activities. Coupled with the formal structures are informal practices that influence the well-being of Burmese in the province. Some of these practices exacerbate the impact of the formal structures, such as gender discrimination and harassment by the authorities. However,there are informal practices that circumvent legal discrimination, which serves to lessen the extentof segmentation, and thus mitigating the incidence of poverty.

Thai Identity Cards The first national census to register citizenship was conducted in 1956, but it did not includesome ethnic minority groups (i.e. highlander or hill-tribe groups), excluding many residents of Mae Hong Son Province. 74 It was not until a limited census conducted in 1969-1970 that many highlander groups received any official recognition.75 This census resulted in the Ministry of Interior granting 120,000 people from highlander groups, Thai citizenship in December 1974(Lertcharoenchok 2001:1). The Ministry of Interior also issued regulations providing for othermembers of these highlander groups, who had entered Thailand prior to 1975, eligible forcitizenship (Renard 2001:53-54). Since then, there have been several official registrations in theNorthern Provinces of Thailand, which have increased citizenship amongst highlander communities.76 There have also been other similar registration processes, which have allowedmembers of other designated communities to reside legally in Thailand.

The registration process which determines residency status and consequently citizenshipcategorizes people on the basis of ethnicity, country of origin and time of arrival in Thailand. 77

The policy has allowed some people, who have fled Burma to legally reside (at least temporarily)in Thailand, providing increased security of residency. Prior to being issued with Thai identity cards, many migrant workers had been arrested (and jailed) for immigration violations.78 Many

74 The Thai Nationality Act (1911) initially granted citizenship to all persons born in Thailand, but this legislation hasbeen amended circumscribing the link between birth and citizenship. In 1972, citizenship rights were restricted topersons whose paternal grandfather was not a Thai citizen. (Lertcharoenchok 2001:1) The Thai Nationality Act wasagain amended in 1992 to specify that someone born in Thailand is not a citizen, if their mother or father had only been granted temporary residency (presumably the holder of either a pink or blue identity card) or was resident in

Thailand without permission. (ACHR 2005:2)

75 There have since been numerous though seemingly incomplete surveys and registration of highlander populationsin Thailand. Major surveys were conducted in 20 provinces of Thailand between 1985 and 1988. Even these resultsappear to be incomplete due to the uncoordinated involvement of several government agencies and the movementsof people (Aguettant 1996).76 The situation of the smaller ethnic groups was one of the King Bhumibols and his mothers early interests. King Bhumibols mother, Princess Mother Sangwal became the patron of the Border Patrol Police (BPP) and thehighlander groups. She sponsored new schools and health clinics with money from the Thai government and thepublic. However, the funding of these projects under the auspices of the royal family was small compared with thosefunded by the Thai and United States government. (Handley 2006:167,190).77 The registration process though often granting limited residency rights to people originally from Burma and theirdescendants has meant that the Thai authorities have not had engage in the difficult and politically sensitive policy of attempting to deport people to countries where they are not legally recognized (and not wanted). The policy doeshowever allow the government to document and monitor their presence until they are prepared (or can) make aconclusive decision regarding their status.

78 For example the husband in interview 23 had been arrested 5 times, between 1985 and 1990 before being issued with a blue identity card. Once he was arrested while working on the Kings Palace in the Province and the other 4

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

22/38

22

of the Burmese refugee migrants who have resided in the province prior to 1999 hold one of four different identity cards, which grant different legal rights and access to services. Theseidentity cards are identified by their respective colour the pink card, the blue card, the light

pink (or orange card) and the green card with the red border . However, the system of registration issomewhat of a muddle, as is the policy and the authorities engaged in its determination, with

substantial attendant corruption, stonewalling and incompetence (Aguettant 1996; Jarenwong 1999). Some of the confusion within the system derives from the difficulty identifying andcategorizing people as belonging to particular groups and the ambivalence the Thai authoritieshave towards some communities resident in Thailand. Sometimes the village head uses anunspecified, unformulated good citizen test to determine whether certain people from Burmaobtain Thai identity cards.

Pink Card In 1977, people from Burma resident in some of the Northern Provinces of Thailand wereissued with the pink card, which must be renewed every six years. This card allows the holder toreside anywhere in the province of issue, but official permission must be obtained to visit other

provinces in the country. This card does not allow the holder to claim formal title over land or thelegal right to work (which requires a work permit). Their children are allowed to attend schooluntil year twelve, but do not have the right to attend university.

Hill-Tribe or Blue Card Another registration of people from highlander groups was conducted in 1990-1991 in theNorthern provinces, with those registered receiving a hill-tribe or blue card. 79 Again, the holdersof this card have no right to legal employment at least not in the urban areas, though a limitednumber of people originally from Burma holding the card have obtained formal title over land forthe purpose of housing. Again, the holder is prevented from travelling outside the provinceunless permission is obtained from the head of the local district. If an absence is for more than

10 days, permission must be granted by the local governor (ACHR 2005:2). During the first yearof registration in Mae Hong Son only about 20 people from Burma, all reputably Kayah wereregistered, but government change and a more liberal implementation, led to an increase in thenumber of people from Burma registered. 80 It was difficult for many refugee migrants fromBurma to obtain this card as the Mae Hong Son authorities were reluctant to register any Burmese. The children of those holding the hill-tribe card have the right to attend university,unlike all the other cards held by those originally from Burma. All those holding the blue carddo not have the same rights and access to services with this apparently determined on the basisof ethnicity.

Light Pink Card

The third identity card issued to some originally from Burma was the light pink card (sometimesknown as the orange card). This was issued in 1995, but only about 500 people were everregistered under this system.81 The holders of this card cannot leave their village or sub-districtunless permission is granted by the governor of the province. The holder to leave the provincerequires the permission of the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Interior (ACHR 2005:2).

The children of the holders of this card are only entitled to attend the first six of school.

times at his home. He was never deported, but jailed for 50 days with the first arrest, then for 28 days with eachsubsequent arrest.79 250,000 people were registered during this period and granted the blue card (Lertcharoenchok 2001:1).80 Interview 1 Karen Male 65, Karenni: Arrived 197681 It seems that the light pink card was aimed specifically at Burmese political activists, who had fled after the 1988uprising and not specifically members of highlander groups.

-

8/6/2019 2006 Employment and Poverty in Mae Hong Son

23/38

23

Green Card with a Red Border In 1999, another survey was conducted in the Northern provinces for the purpose of registering people, who were illegally resident in Thailand. Those registered were issued the green card with a red border. Again, some from Burma were issued with the card, which has the same restrictive

residency rights as those holding the light pink card, except the holders of this card areconsidered aliens with only temporary rights to reside in Thailand, though this right has beenextended each year, since the card was first issued in 1999.82 The children of these card holdershave the same limited entitlements to attend school as the children of those holding the light

pink card.83

No Identity Card Nearly, all those surveyed held one of the four Thai identity cards, but this does not necessarily reflect the broader migrant worker population in the province. Not all the long term residentsin the province originally from Burma hold Thai identity cards, as some have fallen outside theregistration process.

There are about 15 men and women living on the outskirts of the village in the fields without any identity card.Some come from Mae Aw and some from Karenni and Shan State. Some of these people hung around the border area for a long time, but took much longer to come into Thailand. This is why they do not have any cards, but they are not new arrivals.[Interview 14 Karen Male 23, Shadaw Township, Karenni: Arrived1980]

However, those without identity cards and illegally resident in Mae Hong Son Province typically fled Burma after 1999.

About 25 per cent of the people in this quarter do not have any Thai ID cards, as they have only arrived recently.[Interview 19 Shan Woman 31, Southern Shan State: Arrived in 1991]

82 In August 2000 the Thaksin government categorized highlander s resident in Thailand into 3 groups, which donot fully correspond with the categories of people established under the registration system;

i) Those who migrated to Thailand between 1913 and 1972 became eligible to apply for citizenship. This would apply to some Burmese who arrived in Mae Hong Son Province in this period. (The author meta number of people from Burma, who had fled in the 1960s and early 1970s. Some of these peopleheld Thai citizenship. Others, even one family, who has been resident in Thailand for threegenerations, had fallen completely outside the registration system.)