(2005)Spatialtemp.preps

-

Upload

natasha-mills -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

description

Transcript of (2005)Spatialtemp.preps

-

Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806

The spatial and temporal meanings ofcan be independently im

a,b,

Psychob D eurosci

ecembe

Abstract

English u lationsworldwide e plainethat humans have a cognitive predisposition to structure temporal concepts in terms of spatial schemas through the application of a TIME ISSPACE metaphor. Evidence comes from (among other sources) historical investigations showing that languages consistently develop in sucha way that expressions that originally have only spatial meanings are gradually extended to take on analogous temporal meanings. It is notclear, however, if the metaphor actively influences the way that modern adults process prepositional meanings during language use. To explorethis question, a series of experiments was conducted with four brain-damaged subjects with left perisylvian lesions. Two subjects exhibitedthe followinknowledge oof prepositioopposite disthe spatial anormally be 2004 Else

Keywords: L

1. Introdu

An intritions are utionships (T1983; Lind1999; amoof this genenot universilies worldw

The researNeurology at Present ad

Heavilon HalTel.: +1 765 4

E-mail ad

0028-3932/$doi:10.1016/jg dissociation: they failed a test that assesses knowledge of the spatial meanings of prepositions, but passed a test that assessesf the corresponding temporal meanings of the same prepositions. This result suggests that understanding the temporal meaningsns does not necessarily require establishing structural alignments with their spatial correlates. Two other subjects exhibited the

sociation: they performed better on the spatial test than on the temporal test. Overall, these findings support the view that althoughnd temporal meanings of prepositions are historically linked by virtue of the TIME IS SPACE metaphor, they can be (and may) represented and processed independently of each other in the brains of modern adults.vier Ltd. All rights reserved.

anguage; Metaphor; Parietal lobe; Semantics; Space; Time

ction

guing feature of English is that many preposi-sed to describe both spatial and temporal rela-able 1; Clark, 1973; Bennett, 1975; Jackendoff,stromberg, 1998; Rice, Sandra & Vanrespaille,

ng others). Remarkably, spacetime parallelismsral nature are cross-linguistically quite common ifal. In a survey of 53 languages from diverse fam-

ide, Haspelmath (1997; see also Traugott, 1974,

ch reported in this paper was conducted in the Department ofthe University of Iowa.dress: Department of Audiology and Speech Sciences, 1353

l, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907-1353, USA.94 3826; fax: +1 765 494 0771.dress: [email protected].

1978) found that all of them, without exception, employ spa-tial expressions for temporal notions. In addition, he discov-ered similarities as well as differences in how spacetime par-allelisms are manifested. For example, expressions for topo-logical spatial relationships like coincidence (at the corner),superadjacency (on the table), and containment (in the closet)are also frequently used to indicate that an event occurred si-multaneously with a particular clock time (at 1:30), day-part(in the morning), day (on Monday), month (in July), season(in the summer), or year (in 2003); however, there is a greatdeal of cross-linguistic variation regarding not only the pre-cise spatial notions that are lexically encoded (Levinson &Meira, 2003), but also which ones are associated with whichtime periods.

Why are spacetime parallelisms so common cross-linguistically? Several explanations have been proposed (see

see front matter 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved..neuropsychologia.2004.06.025David Kemmerera Department of Audiology and Speech Sciences and Department of

epartment of Neurology, Division of Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive NReceived 3 September 2003; received in revised form 9 D

ses the same prepositions to describe both spatial and temporal rexhibit similar patterns. These spacetime parallelisms have been exEnglish prepositionspaired

logical Sciences, Purdue University, USAence, University of Iowa College of Medicine, USAr 2003; accepted 7 June 2004

hips (e.g., at the corner, at 1:30), and other languagesd by the Metaphoric Mapping Theory, which maintains

-

798 D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806

Table 1Spacetime parallelisms of English prepositions

Space Time

Shes at the cHer book is o

Her coat is in

She left her karound her

She plantedthe tree and

She ran throuShe hung the

the tableShe swept th

the rugShe painted t

studio

Haspelmatbe most coMapping TRamscar, 22002; Hein2002; Lako1998). Onemetaphor iis instead asignificantlman cognidifferent colowing canprojected iof meaningologicallyBowdle, Wparallelismthe three-dconcrete anmain of timare given gtional strucof a TIMEtime can beand this simused to encner, at 1:30(1997) docspacetimeable in howflexibility aof the Metpatterns orconceptualways.

Evidencchange in

holds that the conceptual domains of space and time are asym-metrically related because the direction of influence only goesone way, with spatial concepts providing familiar relational

tures tasymmshoulmean

cess oHaspexcepterma

sed onouse)the sp

va, 20dditiomentpicallsisten

tures arovidi; E. Cuce linmporspatiaowerm

I have

alloobeen

y wegh spa

y is cand S

is leaACEroces

is a costinguorner She arrived at 1:30n the table Her birthday is onMonday/October

6ththe closet She left in the morning/July/the

summer/2003eys somewheredesk

She had dinner around 6:30

flowers betweenthe bush

She likes to run between 4:00 and5:00

gh the forest She worked through the eveningchandelier over She worked over 8 hours

e crumbs under She worked under 8 hours

he picture in her She painted the picture in an hour

h 1997, for a review), but the one that appears tonsistent with the available data is the Metaphoricheory (e.g., Boroditsky, 2000, 2001; Boroditsky &002; Gentner, 2001; Gentner, Imai & Boroditsky,e, Claudi & Hunnemeyer, 1991; Heine & Kuteva,ff & Johnson, 1999, 2003; McGlone & Harding,of the fundamental tenets of this theory is that

s not merely a literary or rhetorical device, butpowerful computational ability that contributes

yand perhaps uniquely (Gentner, 2003)to hu-tion by allowing similar relational structures innceptual domains to be identified, and also by al-didate inferences from the base domain to bento the target domain, thereby enabling a kind

creation (see Hummel & Holyoak, 2003, for bi-inspired computer simulations; see also Gentner,olff & Boronat, 2001). With respect to spacetimes, the Metaphoric Mapping Theory maintains thatimensional domain of space is inherently mored richly organized than the one-dimensional do-e, so the relational structures of temporal conceptsreater coherence by being aligned with the rela-

strucThistionsporala provey,that eple, Gis bathe hfromKute

Avelopare tyis construcbly p1973proding tewithby B

Can

The bhave

Todaenou

Fridaurday

ThIS SPand pThisbe ditures of spatial schemas through the application

IS SPACE metaphor. For example, moments inconstrued as being analogous to points in space,ilarity may account for why the preposition at isode both kinds of information (e.g., at the cor-). The cross-linguistic variation that Haspelmath

umented regarding the specific manifestations ofparallelisms shows that some flexibility is avail-correspondences are formulated; however, this

ppears to be constrained, and an important claimaphoric Mapping Theory is that the most regulariginate from a universal human predisposition toize time in terms of space in certain preferential

e for this theory comes from research on semanticlanguages over the course of history. The theory

The stroprepositioncation of thof the relatiderived frotial meaninand projecta sentenceturing the cof a point ohypothesisin the fieldparently enstatement fthink abouhat help make temporal concepts more coherent.etry predicts that the spatial meanings of preposi-

d always be chonologically primary, and that tem-ings should emerge from them gradually throughf semantic extension. In his cross-linguistic sur-lmath (1997) confirmed this prediction and foundions are virtually unattested (p. 141). For exam-n vor before (as in vor August before August)vor in front of (as in vor dem Haus in front ofbecause the temporal sense developed historicallyatial sense (see also Heine et al., 1991; Heine &

02; Hopper & Traugott, 2003).nal support for the theory comes from language de-in children. The spatial meanings of prepositionsy acquired before the temporal meanings, whicht with the notion that these two kinds of semanticre asymmetrically related, with the former possi-ng a conceptual foundation for the latter (H. Clark,lark, 1974). Also, preschool children sometimesguistic errors that reveal a mind creatively shap-

al concepts by establishing novel correspondencesl schemas, as in the following utterances reportedan (1983):

any reading behind [=after] the dinner?ns is on the other side, after I ate. But there mightmore on the first side [=before eating].ll be packing because tomorrow there wont bece to pack.

overing Saturday and Sunday so I cant have Sat-unday if I dont go through Friday.

ds naturally to the question of whether the TIMEmetaphor plays an active role in the representationsing of prepositions for modern adult speakers.ntroversial issue. Two alternative hypotheses canishedthe strong view and the weak view.ng view maintains that the temporal meanings ofs are always computed through the on-line appli-e TIME IS SPACE metaphor. In other words, partonal structure of these meanings is always activelym the relational structure of the corresponding spa-gs through processes of cross-domain alignmention. According to this hypothesis, understandinglike She arrived at 1:30 necessarily involves struc-oncept of a moment in time in terms of the conceptn a line. The strong view is obviously a very bold, but it is not just a straw man. Some researchersof cognitive linguistics (Croft & Cruse, 2004) ap-dorse this position, as indicated by the followingrom Lakoff and Johnson (1999, p. 166): Try tot time without any of the metaphors we have dis-

-

D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806 799

cussed. Try to think about time without motion and space . . ..We have found that we cannot think (much less talk) abouttime without those metaphors. That leads us to believe thatwe conceptualize time using those metaphors and that sucha metaphorical conceptualization of time is constitutive, atleast in significant part, of our concept of time.1

By contmeanings odependentlderstandingapplicationword breakmeal in terat 1:30 doepoints on aways availathe cross-limental datan inherenpoint is simmapping isthe weak v

The goaing hypothwell-establkinds of c& Caramaposes, the mconcepts cthough thestract concso-called coHoward &1969; Martcases of th(Breedin, S1995; SirigWarringtonstract conctrophysioloHolcomb,2004; Mell2000) pattespatial conones, it wothese two tfrom each oif a subjecttions is imptions in a teit is assumcess to thei

1 A similarmetaphoric uan opportunit

grounded. However, the weak view predicts that the spatialmeanings could be impaired without necessarily affecting thecorresponding temporal meanings, because the latter are as-sumed to be processed independently of the former. Thesecompeting predictions were explored in an experiment de-scribed below.

ethod

Subjec

. Braiur su

ge cathe Pagnitiv

t the se imaglesion, 199

s comprotocel, 19

.1. Suwith 1in 199r/prefon ofinal athe sue. Thh has

.2. Suan witcause

refronnferioector

initiallsting s

.3. Suwithsphereosterimargie supee. Acesolveual agrast, the weak view maintains that the temporalf prepositions are represented and processed in-y of the corresponding spatial meanings, so un-

the former does not necessarily involve on-lineof the TIME IS SPACE metaphor. Just as thefast does not require one to think of a morning

ms of breaking a fast, so the sentence She arriveds not require one to think of time as a series ofline. Certainly active metaphoric mapping is al-ble as an optional processing strategyafter all,nguistic data (and to a lesser extent the develop-a) suggest that the TIME IS SPACE metaphor ist design feature of the human brain. The crucialply that, according to this hypothesis, metaphoricnot obligatory. A more detailed consideration of

iew is presented in Section 4.l of this paper is to evaluate the two compet-

eses from a neuropsychological perspective. It isished that focal brain lesions can impair certainoncepts while leaving others intact (see Martinzza, 2003, for recent reviews). For present pur-

ost relevant finding is that concrete and abstractan be disrupted independently of each other. Al-most common dissociation involves impaired ab-epts and preserved concrete conceptsi.e., thencreteness effect (e.g., Coltheart, 1980; Franklin,Patterson, 1994; Goodglass, Hyde & Blumstein,in, 1996; Tyler, Moss & Jennings, 1995)severale opposite dissociation have also been reportedaffran & Coslett, 1994; Cipolotti & Warrington,u, Duhamel & Poncet,1991; Warrington, 1975;& Shallice, 1984). Moreover, concrete and ab-

epts have been associated with different elec-gical (Weiss & Rappelsberger, 1996; West &2000) and hemodynamic (Fiebach & Friederici,et, Tzourio, Denis & Mazoyer, 1998; Wise et al.,rns in the brains of normal subjects. Given thatcepts are arguably more concrete than temporaluld be of theoretical interest to determine whetherypes of prepositional meaning can be dissociatedther by brain injury. The strong view predicts thats knowledge of the spatial meanings of preposi-aired, his or her ability to use the same preposi-mporal context should also be disrupted, because

ed that the temporal meanings always require ac-r spatial correlates in order to be metaphorically

proposal was recently made about the interpretation ofses of action verbs like graspe.g., grasp an idea or graspy (Feldman & Narayanan, 2004).

2. M

2.1.

2.1.1Fo

damafromof Coabounanc

jectsFrankstatudard(Tran

2.1.1man

CVAmotoportimargtor offissurwhic

2.1.1wom

1995tor/pthe irior swas

persi

2.1.1man

hemithe psupraof thfissurally rresidts

n-damaged subjectsbjects with circumscribed left-hemisphere brainused by cerebrovascular disease were selectedtient Registry of the University of Iowas Divisione Neuroscience. The information provided belowubjects lesion sites comes from magnetic reso-ing scans that were used to reconstruct each sub-in three dimensions using Brainvox (Damasio &

2). The information about the subjects languagees from tests that are part of the battery of stan-ols of the Benton Neuropsychology Laboratory

96).

bject 1. 1760KS is a 47-year-old right-handed2 years of education. He suffered a left-hemisphere1 that damaged most of the posterior inferior pre-

rontal cortex and underlying white matter, a smallthe inferior pre- and postcentral gyri, the supra-nd angular gyri, the insula, and the posterior sec-perior temporal cortex, extending into the sylvian

e lesion caused a very severe Broca-type aphasiaremained stable.

bject 2. 1978JB is a 54-year-old right-handedh 12 years of education. A left-hemisphere CVA ind a lesion involving the posterior inferior premo-tal cortex extending deep into the basal ganglia,r half of the pre- and postcentral gyri, the ante-of the supramarginal gyrus, and the insula. Shey a global aphasic; however, this resolved into aevere Broca-type aphasia.

bject 3. 1962RR is a 70-year-old right-handed18 years of education. He experienced a left-CVA in 1991 which damaged a small portion of

or inferior premotor/prefrontal cortex, the entirenal and angular gyri, and the posterior two-thirdsrior temporal gyrus, extending into the sylvian

utely he displayed global aphasia, but this gradu-d into a predominantly anomic aphasia with somerammatism.

-

800 D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806

2.1.1.4. Subject 4. 2127HW is a 59-year-old right-handedwoman with 11 years of education. Her lesion, which oc-curred in 1997, is predominantly in two regions of the whitematter of thperior andlateral ventcortices; anbody of ththe sylvianguage werthe chronicaphasia nodifficulty.

The fi1962RRrolinguisticrelevant tosubjects mabattery ofthe spatialprepositionKemmerer,current studfor comparmeanings ofor all of thphotographspatial relaabove, thelikely dueof the preptrouble witprocessing

2.1.2. NorThe fou

10 neurolomale and fi8.6), and av

2.2. Tests

2.2.1. Assepreposition

Subjectsas the MatcThe stimulobjects thaIn each picis the focuslandmarkfor locatingon normatigle preposiback of anddetermine

picted spatial relationship. For instance, one picture shows acap lying on the supporting surface on a chair, and the subjectmust indicate which preposition best completes the sentence

cap iscarefuus typllowigh, ov, andetails)

. Assesitionbjects

h has 6mpletein thisinghe prires areoral Mtest bare to

ist of 1rent asened .ed . . .

licity amoun

ct is tessedtermisitionand u

patialrent ty

orderminethe o

ifyingsing t

undersed byllows:ing);(e.g.,). For

timeer ofbe don

sitionple, sarray

d to wtimee left hemisphere. One region is in the territory su-lateral to the frontal horn and anterior body of thericle, subjacent to the middle and inferior frontald the other, smaller region is near the posterior

e lateral ventricle, subjacent to the terminus offissure. In the acute epoch, her speech and lan-

e consistent with transcortical motor aphasia; inepoch, she manifested a stable mild non-fluent

table for hesitancy and occasional word-finding

rst three subjects1760KS, 1978JB, andhave participated in several previous neu-

investigations. The findings that are mostthe current study are as follows. First, all of thenifested consistently poor performance on a large

tests that focus on multiple ways of processing(more specifically, the locative) meanings of

s (Kemmerer & Tranel, 2000, 2003; Tranel &in press). Only one of the tests was used in they, however, because it was deemed most suitable

ison with a new test that focuses on the temporalf prepositions (see below). Second, the stimulie tests in the spatial prepositions battery includes and line drawings of concrete entities in varioustionships, but as noted in the references citedsubjects difficulties with the tests were most

to impaired knowledge of the relevant meaningsositions, since none of the subjects had significanth a variety of other tests that evaluate visuospatialand visual object recognition.

mal control subjectsr brain-damaged subjects were compared with

gically healthy right-handed control subjects, fiveve female. Average age was 50.1 years (S.D. =erage education was 13.6 years (S.D. = 2.2).

ssing knowledge of the spatial meanings ofswere given the Spatial Matching Test (referred to

hing #1 Test in Kemmerer & Tranel, 2000, 2003).i include 80 black-and-white photographs of realt bear certain spatial relationships to each other.ture, the figure (i.e., the object whose locationof attention) is indicated by a red arrow, and the(i.e., the object that serves as a point of referencethe figure) is indicated by a green arrow. Based

ve data, each picture is associated with either a sin-tion or with two very similar prepositions (e.g., inbehind). For each picture, the subjects task is to

which of three prepositions best describes the de-

Thewere

variothe fothrouhind)for d

2.2.2prepo

Suwhicto coonlymean

in). TpictuTemplattertionscons

diffehappfinishsimpthe asubje(expron deprepoover,

the Sdiffe

Indeterwithidentacces

andpressas fomorn

year1859clocknumbmustbasedprepoexam

same

regarclockin/on/beside the chair (answer = on). The itemslly designed to probe the subjects knowledge ofes of categorical spatial distinctions captured byng English prepositions: on, in, around, between,er, under, above, below, in front of, in back of (be-beside (next to) (see Kemmerer & Tranel, 2000,.

ssing knowledge of the temporal meanings ofswere also given the Temporal Matching Test,

0 items. As in the Spatial Matching Test, the task isa sentence by selecting one of three prepositions,case the context calls for a temporal, not a spatial,e.g., It happened through/on/in 1859 (answer =ncipal difference between the two methods is thatused in the Spatial Matching Test but not in theatching Test (pictures were not included in the

ecause the temporal meanings of most preposi-o abstract to be clearly depicted). The 60 items5 instances of four sentence frames that focus onpects of event structure: the occurrence itself (It. .), the beginning (It began . . .), the end (It), and the duration (It lasted . . .). The syntacticnd consistency of the sentence frames minimizes

t of language processing that is necessary. Theold that each sentence refers to some vague eventmerely as it), and that he/she should concentratening which preposition is most appropriate. Eights are used: at, on, in, around, between, through,nder. All but one of them (at) are also used inMatching Test. The 60 items instantiate all of thepes of temporal situations illustrated in Table 1.

to perform well on the test, the subject mustwhich prepositional meaning is most compatiblether elements in the sentence. This requireswhich aspect of event structure the verb denotes,he temporal meanings of the three prepositions,tanding the kind of landmark time period ex-the noun-phrase. The landmark time periods areprecise clock times (e.g., 9:15); day-parts (e.g.,

days of the week (e.g., Tuesday); months of theJuly); seasons (e.g., summer); and years (e.g.,two kinds of landmark time periodnamely,

s and yearsthere are a potentially unlimitedpossible instantiations, so the correct prepositionetermined by means of semantic computationscertain rules of English that stipulate whichis associated with which temporal category. For

ome of the test items have the same verb and theof prepositions to choose from, but differ withhether the landmark time period is a particularor a particular year. This is exemplified by the

-

D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806 801

following two items: It happened on/in/at 9:15 and Ithappened at/in/on 1831. Because the first item specifies thatan event coincided with a clock time, the correct prepositionis at, andoccurred dthe otherday-parts,conventionnouns, andlong-term(e.g., in thHowever, aare memor

informationrelationshipfocal eventSuccessfulkind of semthe same asame landmverb is usedtemporal refollowing tand It lastifies a tempgiven thatcontrast, th(i.e., the flandmark tof the exac

Two shoof the kindMatching Tfor landmaforced-choa single notogether wample, Suthe week.included (cyears), andthe Tempocur repeatehappen, anchoiced painto two sesingle refsentence, feach of whone of the fthe correctis as followfrom Iowawhat happethe whole trsentence H

the trip took, (b) just the first part of the trip, or (c) just the finalpart of the trip. Item 3: The sentence He was tired when henished is about (a) just the final part of the trip, (b) the whole

r (c) how long the trip took. Item 4: The sentence Theasted three hours is about (a) how long the trip took, (b)he first part of the trip, or (c) just the final part of the trip.

esults

e control subjects obtained the following average scorese tests: Spatial Matching Test = 97.1% (2.3); Temporalhing Test = 99% (1.3); Temporal Nouns Test = 100%;oral Verbs Test = 95.2% (6.2). The four brain-damagedcts performance profiles are reported below (Fig. 1).60KS selected the correct preposition for only 39 (46%)

e 80 items in the Spatial Matching Test, yet he scored(90%) on the Temporal Matching Testa highly sig-

nt difference (chi-square (1) = 31.2, p < 0.001). 1978JBited aatchichi-sqissociacross

978JBoral Nn the).e oth

e firste Tem1962Ras faand 501). Me sevet ceili

emporledge

. Perforatchingitions,temporbecause the second item specifies that an eventuring a year, the correct preposition is in. Forfour kinds of landmark time periodnamely,days, months, and seasonsthere are only a fewalized instantiations expressed by certain sets offor this reason it is possible that people store inmemory specific preposition-noun collocationse afternoon, on Friday, in May, in the spring).n essential point is that even if such collocationsized, they must be tagged with the semantic

that they are only suitable when the temporalinvolves overlapi.e., occurrence of the

at some point during the landmark time period.performance on the test depends crucially on thisantic knowledge, because some of the items have

rray of prepositions to choose from and also theark time period, but differ with regard to whichand, consequently, with regard to which kind of

lationship is involved. Consider, for example, thewo items: It began through/on/in the eveninged in/through/on the evening. The first item spec-oral overlap scenario, so the correct preposition,

the landmark time period is a day-part, is in. Bye second item specifies a coextension scenarioocal event co-occurs with the entire extent ofime period), so the correct preposition, regardlesst nature of the landmark time period, is through.rt control tests were used to evaluate knowledges of nouns and verbs that appear in the Temporalest. First, the Temporal Nouns Test involves wordsrk time periods. It employs a three-alternativeice paradigm and contains 18 items. For each item,un denoting a particular time period is presentedith three different choices of definitions. For ex-mmer is (a) a year, (b) a season, or (c) a day ofNouns for six different types of time period arelock times, day-parts, days, months, seasons, andthere are three instances of each type. Second,

ral Verbs Test focuses on the four verbs that oc-dly in the Temporal Matching Test: begin, nish,d last. The test employs a three-alternative forced-radigm and contains eight items that are dividedts with four items each. For each set, there is a

erence scenario that is described with a simpleollowed by a series of four additional sentences,ich is based on the reference scenario and includesour verbs. The task is to match each sentence withinterpretation. For example, the first set of itemss. Reference scenario: Imagine that a man droveCity to Chicago. Item 1: The sentence Thatsned is about (a) just the first part of the trip, (b)ip, or (c) just the final part of the trip. Item 2: Thee was tired when he began is about (a) how long

trip, otrip ljust t

3. R

Thon thMatcTempsubje

17of th56/60nificaexhibtwo m97%;the dusedfor 1Tempand o100%

Thof thon thTest.test w35%,< 0.0of thwas a

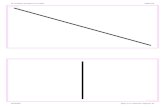

the Tknow

Fig. 1tial Mpreposof thesimilar, albeit milder, dissociation between theng tests (Spatial = 66/80, 83%; Temporal = 58/60,uare (1) = 6.8, p< 0.01). Both subjects manifested

ation for every preposition that was commonlythe tests, the only (minor) exception being under

. In addition, both subjects performed well on theouns Test (1760KS = 100%; 1978JB = 100%)

Temporal Verbs Test (1760KS = 88%; 1978JB =

er two brain-damaged subjects were the oppositetwo insofar as they performed significantly worseporal Matching Test than on the Spatial MatchingR failed both tests, yet his score for the Temporal

r lower than his score for the Spatial test (21/60,6/80, 70%, respectively; chi-square (1) = 16.9, poreover, he manifested the dissociation for five

n prepositions that were used in both tests. Heng on the Temporal Nouns Test, so his failure onal Matching Test cannot be attributed to impairedof the meanings of words for landmark time peri-

mance scores of the four brain-damaged subjects on the Spa-Test, which evaluates knowledge of the spatial meanings of

and the Temporal Matching Test, which evaluates knowledgeal meanings of the same prepositions.

-

802 D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806

ods. However, his score for the Temporal Verbs Test was 6/8(75%), and both of his errors were for the verb nish, whichsuggests that he may have some trouble understanding thisparticular vtremely lowMatching Treflect not omeanings oon, in, andverb nish.on the Spadifficulty w47/60, 78%pattern whwell on botporal Verbson the matcof the temp

4. Discuss

4.1. Doubltemporal m

The dissa lesser extknowledgenecessarilytemporal mthe Spatialpicture shois The balinstead ofcorrectly chappened tothers likethat in is usalized contthat the samoccurred dsimilar findin this studsial questiotively influresented anlenges thederstandingrequires oning spatialweak view,an alignme

If onlyand 1978JBto the follociations of

the Temporal Matching Test both require certain processingmechanisms, but the former test recruits these mechanisms toa greater degree; in other words, it is more difficult. If so, the

ciatioanism

ndents. Ho

llice, 1e addiiallyoral Mresen

eposithey haroces

Funct

e neusitionasio e

anel,uggestructurcortice currpatialRR) at knows forings opic, a

reservoth 19e forJB, anof 17e whie it isatch

ylvianlight

e, 199cal (e.al (e.ggels &r parieh, 200cus oitudesed temnce thfor coeas thtation; Laenerb. If so, this raises the possibility that his ex-score (13%) on the 15 items in the Temporal

est that employ the It finished . . . frame mightnly impaired knowledge of the relevant temporalf the four prepositions that occur in that frame (at,around), but also a comprehension deficit for theFinally, turning to 2127HW, she was unimpaired

tial Matching Test but had a moderate degree ofith the Temporal Matching Test (74/80, 93%, and, respectively; chi-square (1) = 5.9, p < 0.025)a

ich complements that of 1978JB. She performedh the Temporal Nouns Test (100%) and the Tem-Test (88%), suggesting that her poor performancehing test was due to partially defective knowledgeoral meanings of prepositions.

ion

e dissociation between the spatial andeanings of prepositions

ociation manifested robustly by 1760KS, and toent by 1978JB, constitutes evidence that impairedof the spatial meanings of prepositions does notlead to disrupted appreciation of the analogouseanings of the same prepositions. For instance, inMatching Test 1760KS failed an item in which thews a baseball in a baseball glove and the sentencel is on/in/against the glove (he selected againstin); however, in the Temporal Matching Test hehose in for an item in which the sentence is Ithrough/on/in 1859. This example, together withit, suggests that a disturbance of the knowledgeed to specify that an entity is located within an ide-ainer does not necessarily preclude understandinge preposition is also used to specify that an event

uring a particular year. This finding, as well asings involving the other prepositions consideredy, has significant implications for the controver-n of whether the TIME IS SPACE metaphor ac-

ences the way that prepositional meanings are rep-d processed. In particular, the dissociation chal-

strong view, since this hypothesis claims that un-the temporal meanings of prepositions always

-line structural alignment with the correspond-schemas; conversely, the dissociation supports thesince this alternative hypothesis claims that such

nt process is not obligatory.the one-way dissociation manifested by 1760KS

had been found, this study would be vulnerablewing criticism, one that plagues one-way disso-all kinds. Perhaps the Spatial Matching Test and

dissomechdepesition(Shaby thespecTempThe pof prthat tand p

4.2.

Thprepo(Dam& Tries scal stThisin ththe s1962intac

Amean

the toare pfor bdegre1978thoseon thHencthat mperising inNobrologilogicManferioWalsies fomagngrainevidenantwherresen

2003n could be a reflection of damage to these shareds, as opposed to a reflection of damage to an in-neural network for the spatial meanings of prepo-wever, this potential resource artifact criticism988) is obviated, or at least rendered less plausible,tional finding that both 1962RR and 2127HW, butthe former, performed significantly worse on the

atching Test than on the Spatial Matching Test.ce of a double dissociation between the two typesional meaning therefore strengthens the proposalve separate neural substrates and are represented

sed independently of each other.

ionalanatomical issues

roanatomical correlates of the spatial meanings ofs are slowly being elucidated, with neuroimagingt al., 2001) and neuropsychological (Kemmerer

2000, 2003; Tranel & Kemmerer, in press) stud-ing that the left supramarginal gyrus is a criti-e (see also Kemmerer, submitted for publication).al region is damaged in all three of the subjectsent study who exhibited impaired knowledge ofmeanings of prepositions (1760KS, 1978JB, andnd is spared in the single subject who exhibitedledge of these meanings (2127HW).

the neuroanatomical correlates of the temporalf prepositions, this study is the first one to addressnd the data are equivocal. While these meaningsed for both 1760KS and 1978JB, they are disrupted62RR and 2127HW (although to a much greater1962RR), and yet the lesion sites for 1760KS,d 1962RR overlap to a large extent (especially60KS and 1962RR) and also include or encroachte matter regions that are damaged in 2127HW.difficult to identify neuroanatomical dissociationsthe neuropsychological dissociations. Still, the leftcortex appears to be implicated, which is interest-of neuroimaging (e.g., Bellin et al., 2002; Coull &8; Rao, Mayer & Harrington, 2001), electrophysi-g., Mohl & Pfurtscheller, 1991), and neuropsycho-., Critchley, 1953; Harrington & Haaland, 1999;Ivry, 2001) studies indicating that the right in-

tal cortex is important for time perception (see3, for a review). Note, however, that these stud-n the perceptual coding of fine-grained temporal, as opposed to the semantic coding of coarse-poral notions; in addition, there is independentat more generally the right hemisphere is domi-ordinate (i.e., metrically precise) representationse left hemisphere is dominant for categorical rep-s (e.g., Ivry & Robertson, 1998; Jager & Postma,g, Chabris & Kosslyn, 2003).

-

D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806 803

4.3. Methodological issues

A methodological limitation of the current study is that thedesign characteristics of the two matching tests are not per-fectly equathree prepoof the senteentirely onthe spatialstance, in tof the prepable interpmeaning cohand, for thcorrect prein the itemanswer is icompatibleThis methoing tests isovercomingit is worthTemporal Mtical knowthe forms ospecific semencoded inample abovof the otheprepositionentire sentsions It hatorial patte1859, andmatical, onfirst, 1859second, fortime periodtion is in. Tnouns denotext involvnally, bothhappenedforts of mahappened oDetails likestruction ofthat the testheless servknowledgesemantic dodifferentlyinvestigate

2 A new apptence complet

4.4. Rening the weak view

The findings reported in this paper suggest that the TIMEIS SPACE metaphor does not play a necessary role in the

ne processing of prepositional meanings. This does not, however, that the metaphor is dead in the minds ofrn adults. Several studies have shown that when spatialare provided to people, they spontaneously and some-unwittingly exploit them when confronted with tasks

nvolve explicit, linguistically mediated reasoning aboutpresumably because the TIME IS SPACE metaphorseful aid to problem-solving, one that is made prepo-

by the innate design of the human brain. Most of thisrch focuses on two specific metaphors that are com-y used to talk about sequences of events: the ego-movingphor,oward); andes toware

nted smeet

s prefetaph

recediditskystencyditskyguoussdayphorf movr thethat w

nses wfirst p

demon-lingut the ol term/postetimesertica

anings openedThe n

, so thatfor the

ptualizere betteins, 199relativ

ifferencit reflecmore gret al., 1ovitch,ted. For the items in the Spatial Matching Test, allsitions are compatible with the linguistic contextnce, so identifying the correct preposition dependsdetermining which one accurately characterizes

relationship shown in the visual stimulus. For in-he item The ball is on/in/against the glove, allositions yield well-formed sentences with reason-retations, and in is the correct choice because itsrresponds best to the depicted scene. On the othere items in the Temporal Matching Test, only the

position gives rise to a legitimate sentence. Thus,It happened through/on/in 1859, the correct

n because it is the only preposition that is fullywith both the verb happened and the noun 1859.dological discrepancy between the two match-admittedly a limitation of the present study, andit should be a goal of future research. However,

emphasizing that successful performance on theatching Test cannot be reduced to mere statis-

ledge of the brute co-occurrence possibilities off words, but instead depends crucially on quiteantic knowledge of how temporal concepts are

English (cf. Section 2.2.2). Returning to the ex-e (which is, for present purposes, representativer items in the test), although the two incorrectsthrough and onare incompatible with theence frame established by the flanking expres-ppened and 1859, the only two-word combina-rn that is truly ungrammatical is the phrase onin order to recognize that this phrase is ungram-e must appreciate the following semantic points:denotes a time period of the category year; andtemporal overlap scenarios involving this kind of, English stipulates that the appropriate preposi-he preposition through can easily co-occur withting years, specifically when the temporal con-

es coextensione.g., It lasted through 1859. Fi-through and on can easily co-occur with the verbe.g., the sentence It happened through the ef-

ny people specifies causation, and the sentence Itn Tuesday specifies temporal overlap with a day.these were carefully manipulated during the con-the Temporal Matching Test, and while it is true

t does have shortcomings, I submit that it never-es as a useful first attempt to evaluate peoplesof how English prepositions encode the complexmain of timea domain that is treated somewhat

by all the languages that have been systematicallyd (Haspelmath, 1997).2

roach might be to design a three-alternative forced-choice sen-ion test that evaluates knowledge of both the spatial and tempo-

on-liimplymodecues

timesthat itime,is a utentresea

monlmetaline tidaysgressidayspresedaysit waing mthe pBoroconsiBoroambiThurmetaact oline ofoundrespowere

alsocross

abouzontateriorgooduse v

ral meIt hap1859.tenceschoiceconce

they aHawkon theThis dcause

waysHeineKaganwherein the observer progresses along the time-the future (e.g., We are fast approaching the hol-the time-moving metaphor, wherein time pro-

ard the observer from the future (e.g., The hol-coming up fast). McGlone and Harding (1998)ubjects with the ambiguous statement Wednes-ing was moved one day forward and found thaterentially interpreted as Thursday if the preced-oric context was ego-moving, but as Tuesday ifng metaphoric context was time-moving (see also, 2000, and Gentner et al., 2002, on metaphor

effects). Pursuing this line of inquiry further,and Ramscar (2002) discovered that the samestatement was more likely to be interpreted aspossibly reflecting application of the ego-movingif subjects were simply engaged in the physical

ing closer to a goal such as the end of a lunchend of a train ride. In addition, Boroditsky (2000)

hen subjects answered questions about time, theirere significantly faster (129-ms benefit) if theyrimed with spatial schemas. Boroditsky (2001)strated that this priming effect is influenced byistic differences in spacetime metaphors. To talkrder of events, English speakers often use hori-s oriented along the egocentrically grounded an-rior axis (e.g., the bad times behind us and theahead of us), whereas Mandarin speakers often

l termsspecifically, earlier events are said to be

f prepositions with minimally varying items like the following:through/on/in the garden versus It happened through/on/inon-target prepositions in both items yield unacceptable sen-factor is controlled. It is noteworthy, however, that prepositionspatial item depends on complex aspects of how gardens are

d for purposes of linguistic expression in English (e.g., whetherr construed as idealized containers or idealized surfacescf.8), whereas preposition choice for the temporal item dependsely simpler and more abstract knowledge that 1859 is a year.e in semantic complexity and concreteness is unavoidable be-ts the fact that the temporal meanings of prepositions are al-ammaticalized than the spatial meanings (Haspelmath, 1997;991; Heine & Kuteva, 2002; Hopper & Traugott, 2003; Natalyapersonal communication).

-

804 D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806

shang or up, and later events are said to be xia or down.Remarkably, when answering true/false questions about time(e.g., March comes earlier than April), English speakerswere fasterand Mandavertical arr

Overall,be very useto an evenporal percethere is noessary for treports thatspatial reastime doesvation of cconverges nabove, sincthe strongfrom a seradults whictasks, the swere treateal., 1999).impressionTable 1 aretransparent

The facventionalizto made tothe case ththe initial lduring langmeanings etual domaiscaffoldingperspectivecareer of mhaving to esvia metaphcode a temspatial meof time. Hosentation isschemas mtime.

4.5. The babstract la

A numbthe discovestructuringa variety omany thatmain of sp

(2003, p. 16) provides an illuminating listalthough it isonly intended to reveal the tip of an iceberg (e.g., Cienki,1998; Dirven, 1993; Gattis, 2001; Heine et al., 1991; Heine

teva,, 2003)oft in spae vertiture mh and, narr, etc.),

more

for rethe po

lems in. Theemark

owled

is stuute foct Grah Foutzfeldtance,rous fe

rence

, P., M., et al.criminatt, D. (ndon: Litsky, Latial meitsky, Lrin speaitsky, Lstract thrman, Mucturesoboda (rk, NYin, S., Sect iny, 11, 6i, A. (1tensiontti, L.,

ilities:l SocieE. (19

fter. JoH. (19gnitivew Yorkif they had just seen a horizontal array of objects,rin speakers were faster if they had just seen aay.these studies suggest that spatial information can

ful for thinking about time, and other studies pointmore fundamental link between spatial and tem-ption (see Walsh, 2003, for a review). However,evidence that spatial schemas are absolutely nec-emporal reasoning, and in fact Boroditsky (2000)temporal primes do not facilitate performance ononing tasks, which suggests that thinking aboutnot automatically trigger or depend on the acti-orresponding spatial representations. This resulticely with the neuropsychological data presentede both discoveries support the weak view overview. Further support for the weak view comesies of psycholinguistic experiments with normalh demonstrated that in on-line as well as off-linepatial and temporal meanings of at, on, and ind quite differently (Sandra & Rice, 1995; Rice etThese findings are consistent with many peoplesthat spacetime parallelisms like those shown inso conventional that they are not very salient orto awareness (Jackendoff & Aaron, 1991).

t that spacetime parallelisms reflect highly con-ed metaphors allows some theoretical refinementsthe weak view. As noted in Section 1, it may beat the TIME IS SPACE metaphor contributes toearning of the temporal meanings of prepositionsuage acquisition. However, it is likely that thoseventually become stored entirely in the concep-

n of time, so the metaphor can be set aside like athat is no longer needed. From a computational

, this processwhich Gentner (2001) calls theetaphorwould be more efficient than alwaystablish structural alignments with spatial schemas

oric mapping whenever a preposition is used to en-poral meaning. As Boroditsky (2000, p. 4) puts it,taphors may play a role in shaping the domainwever, with frequent use, an independent repre-established in the domain of time, and so spatial

ay no longer need to be accessed in thinking about

roader application of spatial schemas innguage and thought

er of scholars have been justifiably impressed byry that spatial schemas provide a framework fornot just the conceptual domain of time, but also

f other abstract conceptual domainsindeed, soGentner et al. (2001, p. 242) suggest that the do-ace deserves universal donor status. Levinson

& Ku19991985abouor thstruc(higberssetsmuchplaceraiseprobnitiothis r

Ackn

ThInstitProjesearc

Kreuassisgene

Refe

BellinMdis

BenneLo

Borodsp

Borodda

Borodab

BowestrSlYo

Breedeffog

Cienkex

Cipoloabica

Clark,a

Clark,CoNe2002; Kuteva & Sinha, 1994; Lakoff & Johnson,; Lindstromberg, 1998; Pinker, 1989; Radden,

some of the abstract arenas that we routinely talktial terms: kinship (as in close and distant kin,cal metaphor of descent in kinship) and socialore generally (as in high and low status), musiclow tones), mathematics (high and low num-ow intervals, lower bounds, open and closedemotions (high spirits, deep depressions), and(broad learning, a wide circle of friends, the

spect, and so on). These and other considerationsssibility that the capacity to convert non-spatial

nto spatial ones is a key feature of human cog-neurobiological and evolutionary foundations ofable capacity clearly deserve further investigation.

gements

dy was supported by a grant from the Nationalr Neurological Diseases and Stroke (Programnt NS 19632) and by a grant from the Purdue Re-ndation (#01-244). I thank Kathy Jones, Deniset, Ken Manzel, and Daniel Tranel for technicaland Natalya Kaganovitch for extensive and veryedback on previous versions of the manuscript.

s

cAdams, S., Thivard, L., Smith, B., Savel, S., Zilbovicius,(2002). The neuroanatomical substrate of sound duration

tion. Neuropsychologia, 40, 19561964.1975). Spatial and temporal uses of English prepositions.ongman.

. (2000). Metaphoric structuring: understanding time throughtaphors. Cognition, 75, 128.. (2001). Does language shape thought? English and Man-kers conceptions of time. Cognitive Psychology, 43, 122.., & Ramscar, M. (2002). The roles of body and mind inought. Psychological Science, 13, 185188.. (1983). Hidden meanings: the role of covert conceptualin childrens development of language. In D. Rogers & J.

Eds.), The acquisition of symbolic skills (pp. 445470). New: Plenum Press.affran, E., & Coslett, H. (1994). Reversal of the concretenessa patient with semantic dementia. Cognitive Neuropsychol-17660.998). STRAIGHT: an image schema and its metaphorical

s. Cognitive Linguistics, 9, 107149.& Warrington, E. K. (1995). Semantic memory and readinga case report. Journal of the International Neuropsycholog-ty, 1, 104110.74). On the acquisition of the meaning of before andurnal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 10, 266275.

73). Space, time, semantics and the child. In T. Moore (Ed.),development and the acquisition of language (pp. 2863)., NY: Academic Press.

-

D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806 805

Coltheart, M. (1980). Deep dyslexia: a review of the syndrome. London,UK: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Coull, J., & Nobre, A. C. (1998). Where and when to pay attention: theneural sysintervals a18, 7426

Critchley, M.Croft, W., &

bridge UnDamasio, H.,

brain lesiDamasio, H.,

D., & Daand of na

Dirven, R. (1WebbeltWalter de

Feldman, J.,theory of

Fiebach, C. JfMRI evidropsychol

Franklin, S.,deafness.

Gattis, M. (20MIT Pres

Gentner, D. (tis (Ed.),bridge, M

Gentner, D. (MeadowMIT Pres

Gentner, D.,like analoanalogica

Gentner, D., Ifor two sand Cogn

Goodglass, Hturability,

Harrington, Dporal proctional ima

Haspelmath,worlds la

Hawkins, B.selectionTopics injamins.

Heine, B., CChicago,

Heine, B., &Cambridg

Hopper, P. J.Cambridg

Hummel, J. Eof relation220264.

Ivry, R. B.,Cambridg

Jackendoff, Rthan cool

Jager, G., &categoricaevidence.

Kemmerer, Dgrating lin

Kemmerer, D., & Tranel, D. (2000). A double dissociation between lin-guistic and perceptual representations of spatial relationships. Cogni-tive Neuropsychology, 17, 393414.

erer, Danings1435.a, T., &ns: cond.), Korr., B., Ccodinge asymf, G., &iversity

f, G., &icago:

son, S.mbridg

son, S.ologica

e: an e

romberhn Benels, J. Andbook

ycholog, A., &l know, N. (1

one, Mrole oExperi11122t, E., Tatomynary deW., &a move

, S. (1ess.n, G. (1W. Pa

7205). M., M

ain acti7323.S., Sand the frS. Wilcogniti

a, D., &: mirrognitive

ce, T.idge, U, A., Duperienc4, 2555, D. (19nt. In Ineurop

rd Univ, D., &ative p

ott, E.ange, ltems for directing attention to spatial locations and to times revealed by both PET and fMRI. Journal of Neuroscience,7435.(1953). The parietal lobes. Hafner Press.Cruse, D. (2004). Cognitive linguistics. Cambridge: Cam-iversity Press.& Frank, R. (1992). Three-dimensional in vivo mapping of

ons in humans. Archives of Neurology, 49, 137143.Grabowski, T. J., Tranel, D., Ponto, L. L. B., Hichwa, R.

masio, A. R. (2001). Neural correlates of naming actionsming spatial relations. Neuroimage, 13, 10531064.993). Dividing up physical and mental space. In C. Zelinsky-(Ed.), The semantics of prepositions (pp. 3966). Berlin:Gruyter.& Narayanan, S. (2004). Embodied meaning in a neurallanguage. Brain and Language, 89, 385392.., & Friederici, A. D. (2004). Processing concrete words:ence against a specific right-hemisphere involvement. Neu-ogia, 42, 6270.Howard, D., & Patterson, K. (1994). Abstract word meaningCognitive Neuropsychology, 11, 134.01). Spatial schemas and abstract thought. Cambridge, MA:s.2001). Spatial metaphors in temporal reasoning. In M. Gat-Spatial schemas and abstract thought (pp. 203222). Cam-A: MIT Press.2003). Why were so smart. In D. Gentner & S. Goldin-(Eds.), Language in mind (pp. 195236). Cambridge, MA:s.Bowdle, B., Wolff, P., & Boronat, C. (2001). Metaphor isgy. In D. Gentner, K. Holyoak, & B. Kokinov (Eds.), Thel mind (pp. 199254). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.mai, M., & Boroditsky, L. (2002). As time goes by: evidenceystems in processing space time metaphors. Languageitive Processes, 17, 537565.., Hyde, M. R., & Blumstein, S. E. (1969). Frequency, pic-and availability of nouns in aphasia. Cortex, 5, 104119.. L., & Haaland, K. Y. (1999). Neural underpinnings of tem-essing: a review of focal lesion, pharmacological and func-ging research. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 10, 91116.M. (1997). From space to time: temporal adverbials in thenguages. Newcastle, UK: Lincom Europa.(1998). The natural category MEDIUM: an alternative to

retrictions and similar constructs. In B. Rudzka-Ostyn (Ed.),cognitive linguistics (pp. 231270). Amsterdam: John Ben-

laudi, U., & Hunnemeyer, F. (1991). Grammaticalization.IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kuteva, T. (2002). World lexicon of grammaticalization.e: Cambridge University Press., & Traugott, E. C. (2003). Grammaticalization (2nd ed.).e: Cambridge University Press.., & Holyoak, K. J. (2003). A symbolic-connectionist theoryal inference and generalization. Psychological Review, 110,

& Robertson, L. C. (1998). The two sides of perception.e, MA: MIT Press.., & Aaron, D. (1991). Review of Lakoff & Turners Morereason. Language, 67, 320339.Postma, A. (2003). On the hemispheric specialization forl and coordinate spatial relations: a review of the currentNeuropsychologia, 41, 504515.. (submitted for publication). The semantics of space: inte-guistic typology and cognitive neuroscience.

Kemmme

42Kutev

tio(ENa

Laengen

ThLakof

UnLakof

ChLevin

CaLevin

toptiv

LindstJo

MangHaPs

Martintua

MartinMcGl

theof12

Mellean

tioMohl,

inPinker

PrRadde

In17

Rao, Sbr31

Rice,an

&in

SandringCo

Shallibr

Siriguex

11Tranel

me

offo

Tranelloc

Traugch., & Tranel, D. (2003). A double dissociation between theof action verbs and locative prepositions. Neurocase, 9,

Sinha, C. (1994). Spatial and non-spatial uses of preposi-ceptual integrity across semantic domains. In M. Schwartzgnitive Semantikforschung (pp. 215237). Berlin: Gunter

habris, C. F., & Kosslyn, S. M. (2003). Asymmetries inspatial relations. In K. Hugdahl & R. J. Davidson (Eds.),metrical brain (pp. 303339). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the esh. Chicago:of Chicago Press.

Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by (2nd ed.).University of Chicago Press.C. (2003). Space in language and cognition. Cambridge:e University Press.C., & Meira, S. (2003). Natural concepts in the spatiall domainadpositional meanings in crosslinguistic perspec-

xercise in semantic typology. Language, 79, 485516.g, S. (1998). English prepositions explained. Amsterdam:jamins.., & Ivry, R. B. (2001). Time perception. In B. Rapp (Ed.),of cognitive neuropsychology (pp. 467494). Philadelphia:

y Press.Caramazza, A. (Eds.). (2003). The organization of concep-ledge in the brain. New York: Psychology Press.996). Models of deep dysphasia. Neurocase, 2, 7380.., & Harding, J. (1998). Back (or forward?) to the future:f perspective in temporal language comprehension. Journalmental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24,3.zourio, N., Denis, M., & Mazoyer, B. (1998). Cortical

of mental imagery of concrete nouns based on their dic-finitions. Neuroreport, 9, 803808.Pfurtscheller, G. (1991). The role of the right parietal regionment time estimation task. Neuroreport, 2, 309312.989). Learnability and cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT

985). Spatial metaphors underlying prepositions of causality.protte & R. Dirven (Eds.), The ubiquity of metaphor (pp.. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

ayer, A. R., & Harrington, D. L. (2001). The evolution ofvation during temporal processing. Nature Neuroscience, 4,

dra, D., & Vanrespaille, M. (1999). Prepositional semanticsagile link between space and time. In M. Hiraga, C. Sinha,cox (Eds.), Cultural, psychological, and typological issuesve linguistics (pp. 107128). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rice, S. (1995). Network analyses of prepositional mean-ring whose mindthe linguists or the language users?Linguistics, 6, 89130.

(1988). From neuropsychology to mental structure. Cam-K: Cambridge University Press.hamel, J. R., & Poncet, M. (1991). The role of sensorimotor

e in object recognition: a case of multimodal agnosia. Brain,2573.96). The Iowa-Benton school of neuropsychological assess-. Grant & K. Adams (Eds.), Neuropsychological assessmentsychiatric disorders (2nd ed., pp. 81101). New York: Ox-ersity Press.

Kemmerer, D. (in press). Neuroanatomical correlates ofrepositions. Cognitive Neuropsychology.(1974). Explorations in linguistic elaboration: language

anguage acquisition and the genesis of spatio-temporal

-

806 D. Kemmerer / Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 797806

terms. In J. Anderson & C. Jones (Eds.), Historical Linguistics (pp.263314). North Holland: Dordrecht.

Traugott, E. (1978). On the expression of spatio-temporal relations inlanguage. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Universals of human language (pp.369400). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tyler, L. K., Moss, H. E., & Jennings, F. (1995). Abstract word deficitsin aphasia: evidence from semantic priming. Neuropsychology, 9,354363.

Walsh, V. (2003). A theory of magnitude: common cortical metrics oftime, space, and quantity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 483488.

Warrington, E. K. (1975). The selective impairment of semantic memory.Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 27, 635657.

Warrington, E. K., & Shallice, T. (1984). Category-specific semantic im-pairments. Brain, 107, 829853.

Weiss, S., & Rappelsberger, P. (1996). EEG coherence within the 1318H band as a correlate of a distinct lexical organization of concreteand abstract nouns in humans. Neuroscience Letters, 209, 1720.

West, W., & Holcomb, P. (2000). Imaginal, semantic, and surface-level processing of concrete and abstract words: an electrophysio-logical investigation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12, 10241037.

Wise, R., Howard, D., Mummery, C., Fletcher, P., Leff, A., Buchel, C.,et al. (2000). Noun imageability and the temporal lobes. Neuropsy-chologia, 38, 985994.

The spatial and temporal meanings of English prepositions can be independently impairedIntroductionMethodSubjectsBrain-damaged subjectsSubject 1Subject 2Subject 3Subject 4

Normal control subjects

TestsAssessing knowledge of the spatial meanings of prepositionsAssessing knowledge of the temporal meanings of prepositions

ResultsDiscussionDouble dissociation between the spatial and temporal meanings of prepositionsFunctional-anatomical issuesMethodological issuesRefining the weak viewThe broader application of spatial schemas in abstract language and thought

AcknowledgementsReferences