2004-22194-004

description

Transcript of 2004-22194-004

-

4A COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON

HATE AND VIOLENCEAARON T. BECK AND JAMES PRETZER

Whether one considers intimate violence between family members,the carnage of the World Wars, the wholesale slaughter of genocidesaround the world, or the tragic actions of terrorists, the damage that hu-mans can do to each other presents a serious threat to all of us. Theoristsfrom Freud to the present have faced the challenge of developing an un-derstanding of hate and violence. In recent decades, cognitive-behavioral1formulations have proven useful in understanding many aspects of psycho-pathology and in improving treatment efficacy. Recently, a cognitive per-spective on hate and violence has been advanced (Beck, 1999, 2002) inthe hope that it can contribute to our understanding of this serious topicand lead to effective interventions.

'A number of different cognitive and cognitive-behavioral approaches to therapy have been developedin recent years. Although these various approaches have much in common, there are important con-ceptual and technical differences among them. To minimize confusion, we refer to the specific approachdeveloped by Aaron T. Beck and his colleagues as cognitive therapy, whereas the term cognitwe-fcefuwiora!will be used to refer to the full range of cognitive and cognitive-behavioral approaches.

67

-

Role of Cognition in Emotion and Behavior

The cognitive approach developed initially out of observations madein the course of psychotherapy. One seminal insight was the observationthat the content of individuals' thoughts influences their emotional andbehavioral response. Thoughts of failure, rejection, and loss lead to feelingsof sadness and a tendency to give up. Thoughts of gain, achievement, andapproval by others lead to feelings of pleasure and a tendency to keep tryingor to try harder. Thoughts of danger or threat lead to anxiety and a tendencyto avoid. Thoughts of being wronged or mistreated produce anger and an im-pulse to retaliate. The relevant thoughts are fleeting, involuntary, and oftennot recognized by the patient until the therapist teaches him or her to watchfor these automatic thoughts. However, these thoughts often trigger strongemotional reactions and have an important impact on behavior.

A second important insight was the observation that the automaticthoughts that play a role in problems frequently are out of proportion to thesituation that elicits them. For example, an anger-prone individual may blowa minor slight out of proportion, react intensely, and want to punish the of-fender severely. Two factors are seen as contributing to patients' exaggeratedinterpretations of mundane events. First, humans are subject to a variety ofthinking errors, cognitive distortions, which can have a significant impact onthe individual's interpretation of events (see Table 4.1). Anger-prone in-dividuals often interpret impersonal events egocentrically ("Why does thishave to happen to me?"), exaggerate the frequency of noxious events ("Healways does that!"), and exaggerate the severity of noxious events ("Shenever shows me any respect!"). Second, people interpret experiences on thebasis of beliefs and assumptions they have acquired from previous experi-ence. These include unconditional core beliefs such as "I don't count," con-ditional beliefs such as "If you don't have respect, you don't have anything,"and interpersonal strategies such as "You have to make people respect you."These beliefs and assumptions lie dormant until a relevant situation arisesand then automatically become active and shape the individual's responseswhen a relevant situation is encountered. Dysfunctional beliefs can influencewhich aspects of the situation people focus on, how they interpret those ex-periences, and how they respond to them.

Clinical observation shows that, left to themselves, patients typicallyaccept their exaggerations and misinterpretations at face value. When thisis the case, their emotional and behavioral reactions are in proportion tothese dysfunctional automatic thoughts. However, when patients learn tofocus attention on their automatic thoughts, to look critically at them, andto intentionally replace dysfunctional thoughts with more realistic thoughts,this proves useful as one part of helping them overcome their problems. Forexample, when an easily provoked mother was able to recognize her thought"They're bad, they must be punished" and replace it with "They're just

68 BECK AND PRETZER

-

TABLE 4.1Common Cognitive Distortions

Type of distortion Definition ExampleDichotomousthinking

Overgeneralization

Selectiveabstraction

Disqualifying thepositive

Mind reading

Fortune telling

Catastrophizing

Maximization orminimization

Emotionalreasoning

Viewing experiences in termsof two mutually exclusivecategories with no shades ofgray in betweenPerceiving a particular eventas being characteristic oflife in general rather than asbeing one event among many

Focusing on one aspect ofa complex situation to theexclusion of other relevantaspects of the situation

Discounting positiveexperiences that wouldconflict with the individual'snegative views

Assuming that one knowswhat others are thinkingor how others are reactingdespite having little or noevidenceReacting as thoughexpectations about futureevents are established factsrather than recognizing themas fears, hopes, or predictionsTreating actual or anticipatednegative events as intolerablecatastrophes rather thanseeing them in perspective

Treating some aspectsof the situation, personalcharacteristics, or experiencesas trivial and others as veryimportant independent of theiractual significanceAssuming that one'semotional reactionsnecessarily reflect the truesituation

Believing that one is either asuccess or a failure and thatanything short of a perfectperformance is a total failureConcluding that an inconsid-erate response from one'sspouse shows that he or shedoesn't care, despite havingshowed consideration on otheroccasionsFocusing on the one negativecomment in a performanceevaluation received at workand overlooking the positivecomments contained in theevaluationRejecting positive feedbackfrom friends and colleagues onthe grounds that "They're onlysaying that to be nice" ratherthan considering whether thefeedback could be validThinking, "I just know hethought I was an idiot!" despitethe other person's havinggiven no apparent indicationsof his reactionsThinking, "He's leaving me,I just know it!" and acting asthough this is definitely true

Thinking, "Oh my God, whatif I faint?" without consideringthat although fainting may beunpleasant or embarrassing, itis not terribly dangerousThinking, "Sure, I'm good atmy job, but so what? My par-ents don't respect me"

Concluding that because onefeels hopeless, the situationmust really be hopeless

continues

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 69

-

TABLE 4.1 (Continued)Type of distortion Definition Example

"Should"statements

Labeling

Personalization

The use of "should" and"have to" statements that arenot actually true to providemotivation or control overone's behaviorAttaching a global label tooneself rather than referring tospecific events or actionsAssuming that one is thecause of a particular externalevent when, in fact, otherfactors are responsible

Thinking, "I shouldn't feel ag-gravated; she's my mother, Ihave to listen to her"

Thinking, "I'm a failure!" ratherthan "Boy, I blew that one!"

Thinking, "She wasn't veryfriendly today; she must bemad at me" without consider-ing that factors other thanone's own behavior may affectthe other individual's mood

behaving like normal kids," she found that her anger was less intense andsubsided more quickly.

The cognitive model that emerged from observations of patients in psy-chotherapy and research into the role of cognition in emotion and behaviorwas not simply "thoughts cause feelings and behavior." Rather, thoughts areseen as an important part of a cycle through which thoughts influence feel-ings and behavior and through which feelings and actions influence thoughtsas well (see Figure 4.1).

Thus, when the easily provoked mother discussed above was faced withchildish misbehavior, she tended to respond with critical, punitive thoughts

Beliefsand assumptions External

events

Biased perceptionand recall

Automaticthoughts

Responsesof others

MoodInterpersonal

behavior

Figure 4.1. Cognitive-interpersonal cycle.

70 BECK AND PRET2ER

-

(e.g., "He should know better"; "I can't let him get away with this"), andthese thoughts quickly elicited irritation or annoyance. However, the cycledoes not stop at that point. Although thoughts influence mood, mood alsobiases cognition in mood-congruent ways. As a result, once the mother inthis example was irritated or annoyed, she tended to selectively recall herson's previous transgressions, to be vigilant for additional misbehavior, andto have more extreme cognitions in response to continued misbehavior (e.g.,"He always does this!" "If I've told him once, I've told him a thousand times!""He never shows any respect!")- These cognitions, of course, elicited a moreintense emotional reaction that further biased cognition and set the stage foreven more extreme automatic thoughts.

The model depicted in Figure 4.1 has an interpersonal component aswell. Thoughts such as "He's old enough to know better" and "People willthink I can't control my child" are likely to elicit attempts to control thechild's misbehavior. If the mother's initial attempts at controlling her child'sbehavior are effective, then her cognitions are likely to gradually change(perhaps to "He's finally being good"), and her mood is likely to improve.However, if the mother's initial attempts at controlling her child's behaviorare ineffective, the misbehavior is likely to continue, and she is likely to havemore extreme thoughts about her inability to control her child's behavior(perhaps, "What kind of a mother am I if I can't control a 5-year-old? I haveto make him obey!"). This will result in more intense attempts to control thechild's behavior, and if these attempts are unsuccessful, the conflict is likelyto become more and more intense.

Role of Cognition in Hate and Violence

The model described thus far may account for the role that cognitionplays in mundane reactions. However, an understanding of the cognitive-in-terpersonal cycle that results in a mother becoming quite angry with herchild does not provide an understanding of hate and violence. After all, ev-eryone feels angry from time to time, but this momentary experience of angerdoes not usually lead to either hate or violence. Most people who becomeangry handle the situation without punching their antagonist or shooting uptheir workplace.

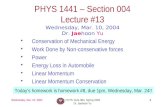

Figure 4.2 summarizes the sequence of events leading to an episode ofspouse abuse. If a man interprets his wife's comments in a way that leaves himfeeling belittled, hurt, or mistreated, this is distressing in itself. However, ifhe sees her behavior as unjustified and inexcusable, then he is likely to seehimself as the victim of mistreatment, to feel angry, and to experience theimpulse to retaliate and punish his wife. The greater the extent to which ad-ditional cognitions legitimize a violent response, the greater the likelihoodof violence (see Beck, 1999, pp. 128-132 and pp. 247-268, for a more detaileddiscussion).

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 71

-

Event

[Wife is critical.]Interpretation

of Event

"She thinks I'm anobody."

DistressedFeeling

Belittled, weak, hurt

SecondaryInterpretation

HostileImpulse

Anger andurge to

punish her

Action

Figure 4.2. Sequence of events in an episode of marital violence.

The cognitive view of "hot" violence (i.e., violence that is associatedwith anger and does not involve prolonged planning and preparation) isbased on the idea that the violently hostile individual often has strong nega-tive biases toward the victim. The greater the degree of bias and distortion,the stronger the affect and the greater the likelihood of violence. In almostall forms of hot violence, the perpetrator or perpetrators believe that theyhave a legitimate grievance and that, therefore, violence is justified. Whenindividuals or groups perceive themselves as having been wronged, dam-aged, coerced, or corrupted by another individual or group, the response isan impulse to retaliate, seek revenge, rebel, or destroy the source of the cor-ruption. In addition, beliefs and perceptions that decrease inhibitions againstviolence or that provide justifications for violence increase the likelihoodthat anger will progress to overt violence. Beliefs such as "Don't get mad, geteven" or "It's them or us" or "God is on our side" can increase the perceptionthat violence is necessary and justified.

When the adversary is demonized (viewed as different, alien, subhu-man, and evil), this intensifies the sense that violence is justified and reducesinhibitions about violence and killing. Under the force of a momentary surgeof anger, thinking becomes more polarized and inhibitions regarding vio-lence decrease, at the same time that the impulse toward violence increases.Often, the results are disastrous. "In the heat of the moment" individuals andgroups may commit acts of violence that they would not normally commitand that they regret deeply once their anger subsides.

72 BECK AND PRETZER

-

Many of the same factors play a role in "cold" violence (i.e., violencethat is the end result of planning and preparation). In this case, the percep-tion (realistic or not) is that one is persistently wronged, damaged, coerced,or corrupted. The response is to feel persistent hatred and to have a con-tinuing desire to retaliate, seek revenge, rebel, or destroy the source of thecorruption. The thinking of terrorists, perpetrators of planned genocide,and others who commit acts of cold violence against persons whom theydo not know personally show a number of cognitive distortions. Theseinclude overgeneralizationthe transgressions of specific members of theenemy group may be seen as characterizing all members of the groupanddichotomous thinkingwe are good, they are bad. In addition, perpetratorsshow tunnel visiona single-minded focus on their image of the enemy tothe exclusion of information and experiences that might contradict theirpolarized view.

The dichotomous thinking in combination with the demonized viewof the enemy enhances the individual or group's self-image (i.e., If I fightthat which is evil, corrupt, and depraved, then I see myself as good, righ-teous, and just). This enhancement of self-image provides an incentive fordichotomous thinking and demonization of the enemy. The greater theextent to which an individual or group has legitimate grounds for feelingvictimized, the fewer distortions are needed to produce a persistent sense ofhaving been wronged and a persistent impulse to retaliate. The greater theextent to which one's family and culture endorse beliefs that justify violenceand views that dehumanize others, the easier it is for persistent hate to cul-minate in violence. Selective association with a group or subculture thatpromulgates views that support hate and violence can greatly reinforce theindividual's own views. However, there need not be legitimate grounds forhate and violence. Individual experiences, cognitive distortions, and idio-syncratic beliefs can lead to hate and violence if the conditions are right.

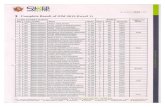

Applying the Cognitive Model to Groups, Cultures, and Nations

The cognitive approach to understanding violence perpetrated bygroups is based on the premise that people are people whether they areoperating individually or in groups. Table 4.2 shows the parallels that Beck(1999) saw in the thinking of individuals who abuse spouses or children, in-dividuals who react violently under provocation, individuals who persecutemembers of other groups, and members of aggressive nations. The nature ofthe perceptions and cognitions that lead to violence are the same whetherthe person is involved in beating a spouse or in a collective assault on mem-bers of another tribe or nation. Thus, if a substantial portion of a group, cul-ture, or nation shares a view that they (or those they care about) have beenwronged by an identifiable adversary and believe that a violent response iscalled for, group-on-group violence is a possible outcome.

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 73

-

TABLE 4.2Commonalities Observed in Hate and Aggression

Across a Variety of Contexts

Factor

Image of selfImage of victimOrientationAttitude towardviolenceThinking

Spouse orchild abuser

Blameless victimVictimizerEgocentricPermissive

Dualistic

Reactiveoffender

VictimVictimizerEgocentricPermissive

Dualistic

PersecutorsVictimVictimizersGroup egoismPermissive

Dualistic

Aggressivenations

VictimVictimizersGroup egoismPermissive

Dualistic

However, in considering hatred, persecution, and violence on a societallevel, it is important to use a broad frame of reference and a level of analysisthat is appropriate to the questions being addressed. For example, an analy-sis of the relationship between economic conditions and hate crimes in theUnited States shows that the lynchings of Blacks in the South increased eachtime economic hardship increased during the years between 1882 and 1930.However, since 1930, economic fluctuations have not been associated withincreases in lynchings. Analysis of the role of racist political elites and orga-nizations shows that they actively fomented resentment towards Blacks andinstigated anti-Black violence. As societal attitudes toward prejudice andanti-Black violence changed over time, these changes stripped racist groupsof much of their power to instigate violence (Green, Glaser, &. Rich, 1998).Cultural attitudes such as the belief that one's group has a history of beingvictimized by a particular group, that one must right current or past wrongs,that the other group is different in a way that makes them less human, orthat violence is the appropriate way to address grievances form the substratefor group violence.

In addition to automatic thoughts and individual factors such as cogni-tive distortions and beliefs that legitimize violence, group interactions canplay an important role in hate and violence. Group conformity can reinforcethe sense of having been wronged, the demonization of the individual orgroup seen as responsible for this, and the conviction that violence is justi-fied. Group interactions that reinforce these views can lead to a much moreextreme response than would be the case if each individual reached theseconclusions separately.

If influential group members endorse extreme views or if the com-munication media are used to spread extreme views, the group as a wholeis moved toward hate and violence. Examples illustrating the impact thatwithin-group communications can have include Hitler's speeches, the role of

74 BECK AND PRETZER

-

radio stations in the Rwandan genocide, and the impact of White suprema-cist Web sites. If group members who are seen as legitimate leaders advocatehate and violence, they can mobilize the rest of the group and legitimizeviolence.

Once a sufficient portion of a group adopts extreme views, those in-dividuals who do not endorse those views may voluntarily leave or may beexcluded from the group. As a result, the group ideology may become moreextreme over time. In addition, influential group members who do not di-rectly commit violence may do a great deal to organize, encourage, and re-ward the violent acts of others. A good general can contribute greatly to theeffectiveness of a fighting force without firing a gun himself.

HOW CAN HATE BE ASSESSED?

Assessing Hate in Individuals

In clinical practice, cognitive therapists find that it often is necessary torely on self-reports because many of the factors of interest, such as automaticthoughts and dysfunctional beliefs, are not directly observable and becauseit is often impractical for the therapist to do extensive in vivo observationand data collection. We recognize that self-reports are an imperfect source ofdata because they are open to a wide range of potential biases and distortions.However, they are often the most practical source of information regardingan individual's day-to-day experiences. Self-report information can be quiteuseful in clinical practice when the therapist can take an active role in help-ing the individual gain access to cognitions that normally operate outside ofawareness and in testing the validity of the self-reports. Table 43 summarizessuggestions for increasing the validity of self-reports adapted from Freeman,Pretzer, Fleming, and Simon (1990).

Unfortunately, there are problems with relying on simple self-reportmeasures in research. Use of this methodology assumes that individualscan reliably report their automatic thoughts and rate the strength of theirdysfunctional beliefs or schemas.2 However, cognitive therapists report thatmany individuals require considerable help before they are able to reliably re-port their automatic thoughts. According to cognitive theory, dysfunctionalschemas often operate outside of awareness, and in clinical practice it oftentakes significant time and effort to identify clients' dysfunctional beliefs.Clear evidence that self-report measures actually assess the cognitions theypurport to measure, not more superficial attitudes, is needed before they are

2$chemas are unconditional core beliefs that serve as a basis for screening, categorizing, and interpretingexperiences (e.g., "I'm no good," "Others can't be trusted," "Effort does not pay off"). Schemas oftenoperate outside of the individual's awareness and often are not clearly verbalized.

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 75

-

TABLE 4.3Guidelines for Increasing the Validity of Self-Reports

Guideline Description1. Motivate the

client to be openand forthright.

2. Minimize thedelay betweenevent and report.

3. Provide retrievalcues.

4. Avoid possiblebiases.

Encourageand reinforceattention tothoughts andfeelings.

6. Encourageand reinforceacknowledgmentof limitations inrecall.

7. Watch forindications ofinvalidity.

Make sure that it is clear that providing full, honest, detailedreports is in the client's interest by

providing a clear rationale for seeking the information, demonstrating the relevance of the information being

requested to the client's goals, and demonstrating the value of clear, specific information by

explicitly making use of the information in therapy.

Minimizing this delay will result in more detailed informationand will reduce the amount of distortion due to imperfectrecall. For events occurring outside of the therapist's office,use an in vivo interview or self-monitoring techniques whenpossible.

Review the setting and the events leading up to the event ofinterest either verbally or by using imagery in order to improverecall.

Begin with open-ended questions that ask the client todescribe his or her experience without suggesting possibleanswers or requiring inference. Focus on "What happened?"not on "Why?" or "What did it mean?" Do not ask clients toinfer experiences they cannot remember. Wait until after theentire experience has been described to test your hypothesesor ask for specific details.

Clients who initially have difficulty monitoring their owncognitive processes are more likely to gradually developincreased skill if they are reinforced for accomplishments thanif they are criticized for failures. Some clients may need explicittraining in differentiating between thoughts and emotions, inattending to cognitions, or in reporting observations ratherthan inferences.

If the therapist accepts only long, detailed reports, thisincreases the risk of the client's inventing data in orderto satisfy the therapist. It is important for the therapist toappreciate the information the client can provide and toencourage the client to acknowledge his or her limits inrecalling details, because incomplete but accurate informationis much more useful than detailed reports fabricated in orderto please the therapist.

Be alert for inconsistencies within the client's report, betweenthe verbal report and nonverbal cues, and between the reportand data obtained previously. If apparent inconsistencies areobserved, explore them collaboratively with the client withoutbeing accusatory or judgmental.

continues

76 BECK AND PRETZER

-

TABLE 4.3 (Continued)Guideline Description

8. Watch for Be alert for indications of beliefs, assumptions, expectancies,factors that may and misunderstandings that may interfere with the client'sinterfere. providing accurate self-reports. Common problems include

the fear that the therapist will be unable to accept the truthand will become angry, shocked, disgusted, or rejecting ifthe client reports his or her experiences accurately

the belief that the client must do a perfect job of observingand reporting the experiences and that he or she is afailure if the reports are not perfect from the beginning

the fear that the information revealed in therapy may beused against the client or may give the therapist powerover him or her

the belief that it is dangerous to closely examineexperiences involving strong or "crazy" feelings for fearthat the feelings will be intolerable or will "get out ofcontrol."

Wofe. From Clinical Applications of Cognitive Therapy (p. 35-36), by A. Freeman, J. L. Pretzer, B. Fleming,and K. M. Simon, 1990, New York: Plenum Press. Copyright 1990 by Plenum Press. Adapted withpermission.

relied upon in research. Alternative methods for assessing relevant cogni-tions are available and should be used more widely. These include ThoughtSampling or Experience Sampling methodology (Hurlburt, Leach, & Salt-man, 1984), laboratory tasks that provide a more direct method for assessingschemas (e.g., McNally, Riemann, & Kim, 1990), and content analysis ofresponses to schema-relevant stimuli (e.g., Eckhardt, Barbour, & Davison,1998).

In assessing beliefs related to hate and violence, it is important toremember that the beliefs may be dormant until they are activated by a rel-evant stimulus. It may be important to "prime" aggressive beliefs through theuse of relevant stimuli to assess them reliably (see Eckhardt et al., 1998).

Assessing Hate in Groups, Cultures, and Nations

To date, cognitively oriented investigators have focused primarilyon individuals, couples, and families and have not yet developed specificmethods for assessing hate in larger social groupings. The theoretical modeldiscussed in this chapter emphasizes the content of individuals' cognitions,the presence of cognitive distortions, within-group communications thatreinforce hate-compatible thoughts and beliefs, and within-group interac-tions that result in suppression of information incompatible with hatred andthe exclusion of group members who hold views that are incompatible withhate. Established research methods used in social psychology, sociology,

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 77

-

anthropology, and related fields should provide useful strategies for assessingthese variables.

HOW CAN HATE BE COMBATED?

Combating Hate in Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy provides one option for combating hate on the indi-vidual level, at least on the occasions when the individual recognizes thathate and violence are a problem and is motivated to change. Exhibit 4.1summarizes the general principles of cognitive therapy. The idea of "col-laborative empiricism" is central to the practice of cognitive therapy. In thecourse of therapy, the cognitive therapist works with his or her client tocollect detailed information regarding the specific thoughts, feelings, andactions that occur in problem situations. These observations provide a basisfor developing an individualized understanding of the client that facilitatesstrategic intervention. Collaborative empiricism continues to play an impor-tant role as the focus of therapy shifts from assessment to intervention. Manyof the specific techniques used to modify dysfunctional thoughts, beliefs, andstrategies emphasize first-hand observation and "behavioral experiments"to test the validity of dysfunctional automatic thoughts or dysfunctionalbeliefs and to develop more adaptive alternatives. Rather than relying onthe therapist's expertise, theoretical deductions, or logic, cognitive therapyassumes that empirical observation is the most reliable means for developingvalid conceptualizations and effective interventions.

Persons unfamiliar with cognitive therapy sometimes assume that cog-nitive therapists focus solely on modifying the individual's cognitions andignore behavioral interventions. It is important to know that a broad rangeof behavioral interventions and emotion-focused interventions are also a

EXHIBIT 4.1General Principles of Cognitive Therapy

Therapist and client work collaboratively toward clear goals.The therapist takes an active, directive role.Interventions are based on an individualized conceptualization.The focus is on specific problem situations and on specific thoughts, feelings, and

actions.Therapist and client focus on modifying thoughts, coping with emotions, and

changing behavior as needed.The client continues the work of therapy between sessions.Interventions later in therapy focus on identifying and modifying predisposing factors,

including schemas and core beliefs.At the close of treatment, therapist and client work explicitly on relapse prevention.

78 BECK AND PRETZER

-

part of cognitive therapy. Table 4-4 summarizes a number of interventionsthat can be used in cognitive therapy with problems of anger, hate, andviolence.

TABLE 4.4Possible Interventions With Anger, Hate, and Violence

Goal Possible interventionsTo reduce If the client tends to suppress or deny anger until he or she reachesthe intensity a "breaking point," help the client recognize the value of deal-of anger in ing with anger before reaching the breaking point and developresponse to adaptive ways of handling anger.provocation If dysfunctional cognitions amplify anger, identify and modify dys-

functional thoughts using "standard" cognitive therapy tech-niques.

Increase understanding of the other person's point of view and feel-ings. Increase understanding of any valid justifications of theother person's behavior.

If it is desirable for the client to be able to respond more calmly inthe face of provocation, use Anger Management Training orStress-Inoculation Training (irnaginal exposure combined withapplied relaxation).

To eliminate Identify cognitions that justify inappropriate expression of anger,maladaptive or and challenge them. Frame problematic expressions of angerinappropriate as inappropriate and unjustified.expression Identify more adaptive alternatives, address cognitions that main-of anger tain dysfunctional behavior or block adaptive alternatives, use(including role-play or imagery to practice the alternatives, implement theviolence) alternatives in situations that are of low to moderate intensity

first and then in more intense situations. Help the client learn toimplement alternative responses before the anger becomes toointense.

Consider simultaneously working to reduce the intensity of anger inorder to facilitate more adaptive responses.

Persistently focus attention on the actual consequences of themaladaptive or inappropriate behavior. Identify alternatives thatproduce better results.

If dysfunctional interaction patterns trigger or perpetuate the prob-lem, consider whether marital, family, or conjoint intervention isneeded.

To increase Identify cognitions that block assertion, and modify them.appropriate Teach assertion skills if necessary.assertion Use role-play or imagery to practice assertion in real-life situations

that are of low to moderate intensity first and then in moreintense situations.

To decrease Watch for cognitions that encourage prolonged anger and addressthe client's them.tendency Address cognitions that intensify anger, and address any tendencyto "hold a to suppress anger.grudge" Identify adaptive alternatives (e.g., communication, assertion, relax-

ation, exercise, "cooling off"), and put them into practice.

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 79

-

Unfortunately, psychotherapy has serious limitations as a means ofpreventing individual or group violence. It is most appropriate when an in-dividual recognizes his or her own hate and violence as a problem and is mo-tivated to change, but many perpetrators of violence do not seek help and donot wish to change. Furthermore, even if more perpetrators of violence werewilling to seek treatment, individual or group psychotherapy is too expen-sive and requires too many resources to be broadly applicable. Methods areneeded for intervening on a societal level to decrease hate and violence.

Combating Hate in Groups, Cultures, and Nations

Strategies applicable with larger groups include reframing individuals'perceptions of the presumed adversary, reducing their emotional investmentin their previously established positions and ideology, encouraging morepragmatic goals, and increasing attention to information incompatible withthe demonized image of the opponent. Unfortunately, interventions usefulin dealing with conflict among individuals or small groups generally are notadequate in volatile political environments. It is difficult to induce leadersto abandon or moderate ideological or self-interested positions. In factionaldisputes, assertion of superior power and determination is often necessary tomove the opponent to a more moderate position where logical argument andpositive experiences in interactions with the opponent can then help resolvethe conflict. However, because dichotomous thinking is more likely whenindividuals feel threatened, the assertion of superior power and determina-tion does not necessarily result in opponents shifting to more moderate andreasonable positions.

Michael Duffy, Kate Gillespie, and their colleagues have establishedthe Centre for Trauma and Conflict Resolution in Omagh, Northern Ireland.Their program for moderating the conflict between Republicans and Loyal-ists (based on Beck, 1999) includes a number of interventions:

psychoeducational sessions for mediators and communityleaders;

group sessions for former opponents; facilitation of meetings where perpetrators of violence and the

victims meet and consider each other's perspectives; the pro-gram includes acknowledgment of suffering, taking responsibil-ity for violent deeds, ventilation and processing of feelings, andchallenging negative appraisals and overgeneralized interpreta-tions of events; and

training therapists who will use their skills in this challengingarea of work.

When intervening with individuals, couples, and small groups, it maybe feasible for the practitioner to remain comfortably in his or her office.

80 BECK AND PRETZER

-

However, in order for interventions to be effective with larger groups,there must be some means of disseminating the interventions throughoutthe larger community. This could include training a corps of individualswho will intervene through the community, making use of the mass media,intervening with influential group members who will then influence othermembers of the community, organizing mass events that have an influencethroughout the community, or organizing ongoing programs that have apersistent effect over time. Programs that incorporate a number of theseinterventions over time should be more effective than those that rely on asingle, short-term intervention.

Group narcissism, in which the interests of the group are pursued tothe exclusion of the interests of other groups, plays a central role in manyconflicts. A long-term antidote would be the establishment of a humanisticorientation as an alternative to tribalism, nationalism, and militant reli-giosity. A moral code emanating from this orientation would incorporateconsidering the other person's perspectives, respecting the rights of others,feeling responsibility for the welfare of others, and balancing one's ownneeds with the needs of others. Although dissemination of this type oforientation is clearly a long-term project, we would expect that the likeli-hood of violent conflict within a community or state would decrease as theproportion of the population with a humanistic orientation increases.

Conflict between states or between a state and external militantgroups, as exemplified by the recent terrorist attacks against the UnitedStates, requires a different level of solution. Although the interventionsdiscussed above are likely to be relevant, it is likely to be necessary for theinterventions to be implemented simultaneously with each of the parties inthe conflict. We hope that understanding each of the antagonists' perspec-tives in cognitive terms will assist in finding solutions.

EMPIRICAL SUPPORT FORTHE COGNITIVE MODEL OF

HATE AND VIOLENCE

Cognitive therapy's general model of the role of cognition in humanfunctioning and in psychopathology is based on a large body of researchaccumulated over several decades. A review of this extensive literature isbeyond the scope of this chapter. In this section we will present a numberof illustrative studies to give an idea of the type of research that supportsthe cognitive perspective and will refer interested readers to sources formore detailed reviews of the literature. The April 2000 volume of Cogni-tive Therapy and Research is devoted to a special issue on cognitive factorsin male intimate violence and provides good coverage of empirical researchinto this topic.

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 81

-

Evidence Regarding the Cognitive Model of Hate and Violence

One of the central principles on which cognitive therapy is based isthe hypothesis that the content of an individual's momentary thoughtsinfluences the emotions that he or she experiences. Wickless and Kirsch(1988) had a large nonclinical sample record their thoughts and emotionswhenever they felt angry, anxious, or sad over a 3-day period and conductedstructured interviews with participants each day. As predicted, they foundthat anxiety was associated with thoughts of threat, sadness was associatedwith thoughts of loss, and anger was associated with thoughts of transgres-sions committed against the participant. In particular, the theme of being"wronged" was most frequently associated with anger.

Experimental confirmation of the role of cognitive distortions in an-ger is provided by the work of Eckhardt and his colleagues (1998). Maleparticipants with and without a history of marital violence verbalized theirthoughts in response to anger-arousing and non-anger-arousing audiotapesdepicting an imaginary interaction with their wives. Responses were codedby trained raters. The results showed that maritally violent men were morelikely than nonviolent men to show three types of cognitive distortions hy-pothesized to contribute to violence: magnification, dichotomous thinking,and arbitrary inference.

After reviewing the available evidence regarding the role of cognitionin marital violence, Eckhardt and Dye (2000) concluded that the empiricalevidence suggests that maritally violent men do, indeed, think differentlythan their nonviolent counterparts. Although there is a need for additionalresearch, and although issues related to assessment methodologies andresearch design complicate interpretation of some studies, the availableresearch provides support for cognitive therapy's hypotheses about the roleplayed by the content of automatic thoughts, attitudes, beliefs, and causalattributions.

Evidence Regarding the Effectiveness of Cognitive TherapyWith Hate and Violence

Quite a few studies have investigated the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) with anger problems. R. Beck and Fernandez(1998) conducted a meta-analysis of 50 studies including a total of 1,640participants. These studies included participants from a wide range of an-ger- and hostility-related domains such as prison inmates, abusive parents,abusive spouses, juvenile delinquents, adolescents in residential treatment,aggressive children, and college students who reported anger problems. Themeta-analysis found that the average CBT recipient was better off than 76%of the untreated participants in terms of anger reduction.

82 BECK AND PRETZER

-

Although there is room for improvement, the empirical support forusing cognitive therapy and related approaches to reduce hate and violencein individuals, couples, and families is encouraging. Ideas for use of theseapproaches on the societal level are of more recent vintage and have not yetbeen the subject of extensive research. Hopes are high among proponents ofthis approach, but the challenge is great, and much remains to be learned.

RELATIONSHIPS TOOTHER PERSPECTIVES ON

HATE AND VIOLENCE

The evolution of cognitive therapy has been influenced by a widerange of theorists and clinicians. In fact, it can be argued that cognitivetherapy is a highly integrative approach (Alford & Beck, 1997; Alford &Norcross, 1991; Beck, 1991). The three primary theoretical influences citedin discussions of the evolution of cognitive therapy have been the phenom-enological approach to psychology, psychodynamic depth psychology, andcognitive psychology (Weishaar, 1993). The clinical practice of cognitivetherapy has been strongly influenced by client-centered therapy and bycontemporary behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches to therapy.Among the influences Beck considered to have been most important arephenomenological perspectives dating back to the Greek Stoic philoso-phers and presented more recently by Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, and KarenHomey; the structural theory and depth psychology of Kant and Freud; thecognitive perspectives of George Kelley, Magda Arnold, and Richard Laza-rus; the emphasis on a specific, here-and-now approach to problems takenby Austen Riggs and Albert Ellis; Carl Rogers's client-centered therapy;the idea of preconscious cognition from writers such as Leon Saul; and thework of cognitive-behavioral investigators including Albert Bandura, Mar-vin Goldfried, Michael Mahoney, Donald Meichenbaum, and G. TerrenceWilson (Weishaar, 1993).

In applying the cognitive perspective to understanding hate and vio-lence, Beck (1999) attempted to incorporate a wide range of perspectivesand to integrate the available data. Psychoanalytic theory has been one ofthe most influential approaches to understanding hate and violence, influ-encing writers in political science, sociology, history, and criminology. Incomparing his cognitive model with psychoanalytic theory, Beck (2002)proposed that the cognitive model is more parsimonious and has stron-ger empirical support. He argued that his generic cognitive model appliesequally well to understanding normal human functioning, psychopathology,and hate and violence.

COGNmVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 83

-

CONCLUSION

The cognitive perspective on hate and violence is consistent with alarge body of empirical research and with the detailed observations madein the course of psychotherapy. It can easily be applied retrospectively toepisodes of hate and violence by individuals and groups as long as sufficientinformation about thoughts and feelings is available. Further studies are nec-essary to test the predictive value of the model and its relevance to effectiveinterventions. Fortunately, the model can generate testable propositions andis amenable to empirical research.

We look forward to future research that will refine and improve thetheoretical model and that will test the effectiveness of interventions andprograms designed to reduce hate and violence. A particular focus on thecollective self-image of antagonistic groups and their image of the Enemycan provide a basis for understanding the conflict. Further, a composite pic-ture of the contrasting perspectives, attitudes, malevolent attributions, andcognitive distortions can facilitate finding political solutions between war-ring factions. Recent decades have demonstrated the vast destructive poten-tial of individuals and groups motivated by hate. We hope that the cognitivemodel can offer a fresh approach to reducing the ubiquitous tendency towardhate and destruction.

REFERENCES

Alford, B. A., & Beck, A. T. (1997). The integrative power of cognitive therapy. NewYork: Guilford Press.

Alford, B. A., & Norcross, J. C. (1991). Cognitive therapy as integrative therapy.Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 1, 175-190.

Beck, A. T. (1991). Cognitive therapy as the integrative therapy: Comments onAlford and Norcross. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, I, 191-198.

Beck, A. T. (1999). Prisoners of hate: The cognitive basis of anger, hostility, and violence.New York: HarperCollins.

Beck, A. T. (2002). Prisoners of hate. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40,209-216.

Beck, R., &. Fernandez, E. (1998). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment ofanger: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 63-74.

Eckhardt, C. I., Barbour, K. A., & Davison, G. C. (1998). Articulated thoughts ofmaritally violent and nonviolent men during anger arousal. Journal of Consult-ing andCfinicaJ Psychology, 66, 259-269.

Eckhardt, C. I., & Dye, M. L. (2000). The cognitive characteristics of maritally vio-lent men: Theory and evidence. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 139-158.

84 BECK AND PRETZER

-

Freeman, A., Pretzer, J. L, Fleming, B., & Simon, K. M. (1990). Clinical applicationsof cognitive therapy. New York: Plenum Press.

Green, E. P., Glaser, J., & Rich, A. (1998). From lynching to gay bashing: Theelusive connection between economic conditions and hate crimes. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 75, 77-92.

Hurlburt, R. T., Leach, B. C., & Saltman, S. (1984). Random sampling of thoughtand mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8, 263-276.

McNally, R. ]., Reimann, B. C., & Kim, E. (1990). Selective processing of threatcues in panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 407-412.

Weishaar, M. E. (1993). Aaron T. Beck. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Wickless, C., &. Kirsch, I. (1988). Cognitive correlates of anger, anxiety, and sad-

ness. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12, 367-377.

COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON HATE AND VIOLENCE 85