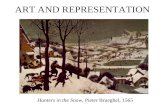

ART AND REPRESENTATION Hunters in the Snow, Pieter Brueghel, 1565.

2001 Research Report...2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 1 Foreword T his year, our cover features...

Transcript of 2001 Research Report...2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 1 Foreword T his year, our cover features...

-

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine

2001 Research Report

Helping People Become Winners

-

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

Department of Orthopaedicsand Sports Medicine

2001 Research Report

-

Cover Illustration: “The Beggars”by Pieter Brueghel, the Elder, 1568Collection of The Louvre, Paris, FranceReprinted with permission ofReunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, New York

Department of Orthopaedics and Sports MedicineUniversity of WashingtonSeattle, WA 98195

EDITORS:Fred WesterbergFrederick A. Matsen III, M.D.

ASSOCIATE EDITORS:Howard A. Chansky, M.D.Ernest U. Conrad III, M.D.Ted S. Gross, Ph.D.M.L. Chip Routt, M.D.Peter T. Simonian, M.D.Kit M. Song, M.D.

DESIGN & LAYOUT:Fred Westerberg

UNIVERSITYOF WASHINGTON

SCHOOL OFMEDICINE

-

Contents

Foreword .................................................................................................................................................................... 1

Sigvard T. Hansen, Jr., M.D., 2001 Distinguished Alumnus .................................................................................... 2

Assessment of NTx and Col2CTx Urine Assay in Endurance Athletes .................................................................. 3

John O’Kane, M.D., Lynne Atley, Ph.D., Chris Hawley, M.D., Carol Teitz, M.D., and David Eyre, Ph.D.

Identification of Matrilin-3 in Adult Human Articular Cartilage .......................................................................... 6

Jiann-Jiu Wu, Ph.D. and David Eyre, Ph.D.

TLS / CHOP Inhibits RNA Splicing Mediated by YB-1 .......................................................................................... 8

Timothy Rapp, M.D., Liu Yang, Ph.D., Ernest U. Conrad III, M.D., and Howard A. Chansky, M.D.

Depth of Countersinking Modulates Cartilage Remodeling in Sheep Osteochondral Autografts ..................... 10

Fred Huang, M.D., Peter Simonian, M.D., Anthony Norman, B.S.E., and John Clark, M.D., Ph.D.

Distal Femoral Tunnel Placement for Multiple Ligament Reconstruction: Three Dimensional ComputerModeling and Cadaveric Correlation ..................................................................................................................... 13

William J. Mills, M.D. and Randy Ching, Ph.D.

Intramedullary Nailing of Distal Metaphyseal Tibial Fractures ............................................................................ 16

Sean E. Nork, M.D., Alexandra K. Schmitt, M.D., Julie Agel, M.A., Sarah K. Holt, M.P.H., Jason L. Schrick, B.S.,and Robert A. Winquist, M.D.

The Association Between Supracondylar Intercondylar Distal Femoral Fractures and Hoffa Fractures ........... 19

Sean E. Nork, M.D., Kamran Aflatoon, D.O ., Daniel N. Segina, M.D., Stephen K. Benirschke, M.D.,M.L. Chip Routt, Jr., M.D, and M. Bradford Henley, M.D., M.B.A.

Triangular Osteosynthesis and Iliosacral Screw Fixation For Unstable Sacral Fractures: A BiomechanicalEvaluation Under Cyclic Loads ............................................................................................................................... 22

T.A. Schildhauer, W.R. Ledoux, Jens R. Chapman, M.D., M.B. Henley, M.D., Allan F. Tencer, Ph.D.,and M.L.Chip Routt, M.D.

Effect of Cervical Lesions on Neural Space Integrity ............................................................................................ 25

Sohail K. Mirza, M.D., D.J. Nuckley, M.A. Konodi, and Randy P. Ching, Ph.D.

Vertebroplasty with a Cavitation Drill .................................................................................................................... 27

A.J. Mirza, M.A. Konodi, Jens R. Chapman, M.D., Carlo Bellabarba, M.D., Randy P. Ching, Ph.D.,Allan F. Tencer, Ph.D., and Sohail K. Mirza, M.D.

The Development and Validation of a Computational Foot and Ankle Model ................................................... 31

William R. Ledoux, Ph.D., Daniel L. A. Camacho, M.D., Ph.D., Randal P. Ching, Ph.D.,and Bruce J. Sangeorzan, M.D.

Mechanical Testing to Characterize the Performance of Shock Absorbing Pylons Used in TranstibialProstheses ................................................................................................................................................................. 33

Jocelyn S. Berge, B.S., Glenn K. Klute, Ph.D., Carol F. Kallfelz, M.S., and Joseph M. Czerniecki, M.D.

The Distribution of Shoulder Replacements Among Surgeons and Hospitals is Significantly Different than thatof Hip or Knee Replacements ................................................................................................................................. 35

Samer S. Hasan, M.D., Ph.D., Jordan M. Leith, M.D., F.R.C.S.C., Kevin L. Smith, M.D.,and Frederick A. Matsen III, M.D.

-

Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: Is There a Correlation Between Phenotype and Genotype? ............................. 37

Gregory A. Schmale, M.D., Ernest U. Conrad III, M.D., and Wendy H. Raskind, M.D., Ph.D.

Intralesional Treatment of Symptomatic Enchondromas and Low-Grade Chondrosarcomas .......................... 40

Scott Helmers, M.D. and Ernest U. Conrad III, M.D..

The Orthopedic Implications of Chemotherapy to Growth in Children ............................................................. 42

Scott Helmers, M.D. and Ernest U. Conrad III, M.D.

Technique of Scapulothoracic Fusion in Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy ........................................ 44

Mohammad Diab, M.D. and Frederic Shapiro, M.D.

Effects of Growth Factors in Combination on In Vivo Flexor Tendon Healing ................................................... 47

Christopher H. Allan, M.D., Sang-Gil P. Lee, M.D., Robert A. Mintzer, B.S., Ho-Jung Kang, M.D.,and Daniel P. Mass, M.D.

Randomized Prospective Trial of Active versus Passive Motion after Zone II Flexor Tendon Repair ................. 49

Thomas E. Trumble, M.D., Richard S. Idler, M.D., James W. Strickland, M.D., Peter J. Stern, M.D.,Shelly Sailer, O.T.R./C.H.T., and Mary M. Gilbert, M.A.

Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine Faculty ................................................................................. 52

Incoming Residents ................................................................................................................................................. 53

Graduating Residents .............................................................................................................................................. 54

New Faculty ............................................................................................................................................................. 55

Research Grants ....................................................................................................................................................... 56

Contributors to Departmental Research and Education ....................................................................................... 60

2001 AAOS Alumni Pictures ................................................................................................................................... 62

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 1

Foreword

This year, our cover features theBeggars, painted by PieterBrueghel the elder 433 years ago.This small painting on wood is shownhere in the same size as it is seen on thesecond floor of the Richelieu wing ofthe Louvre. Closer inspection revealsthat at least three of these beggars havehad amputations of both their legs. Asa result, they need to use their arms forsupport and getting around. Thismakes it impossible for them to work -thus they are reduced to begging. Theirprostheses serve primarily to protecttheir shins from the ground, but onehas tried to build himself up a bit withan added post. These individuals arebeing totally ignored by the figurepassing them by. In contrast, let usconsider the life of Ernest Burgess(1911-2000) who did not pass byindividuals who lost their legs, butrather spent much of his life designingand providing limbs that enabled themto get back up on their feet, to free uptheir arms, to work, to play and to havefamilies. The systems he put in placewill continue to serve, not only in theUnited States where limbs are lost fromtrauma, infection and tumors, but inVietnam, Cambodia, and Afghanistanwhere land mines continue to truncatelimbs and the quality of peoples’ lives.

This has been a most exiting yearfor our Department. We now have anew name: Orthopaedics and SportsMedicine, indicating our commitmentto prevention and to the prompt returnof our patients to optimal function afterinjury or surgery. Thanks to thegenerosity of a select group of Seattlecitizens, we have established the firstEndowed Chair for Women’s SportsMedicine and Lifetime Fitness and arenow well along in our search for the firstholder. The Department and the Chairwere featured in the University’sShowcase event on May 2 and weformally opened our new SportsMedicine Clinic in the Hec EdmundsonPavilion with the help of Rose Bowl-winning Coach Rick Neuheisel on May16.

On the research front, our facultycontinue to achieve at the highest level,with extramural funding, peer-reviewed publications, andrecognitions, such as the Kappa Delta

Clinical Research Award presented thisyear to Bruce Sangeorzan, Allan Tencerand Randy Ching. David Eyre’s groupin the Burgess Laboratories continuestheir pace-setting work in collagenbiology - using the Col2CTx marker ofcartilage turnover along with the NTxmarker of bone turnover. Ted Gross andhis team in the Orthopaedic ScienceLaboratories are exploring bone’sability to self-regulate its mass andmorphology in response to hormonal,metabolic, and physical stimuli. JohnClark has just returned from asabbatical in Switzerland where heexplored new methods of acetabularreconstruction. John Sidles continueshis widely recognized work onmagnetic resonance force microscopy.Howard Chansky and Liu Yang haveformed a new molecular biologylaboratory at the VA where they arejoined by Sohail Mirza and his spineresearch program - soon to besupported by a spine research chair.Steve Benirschke, holder of the DebsChair, has now returned from his NewZealand sabbatical and will bring hisfoot trauma research team to action.Countless other laboratory and clinical

Ernest M. Burgess, M.D., Ph.D.

Best wishes,

Frederick A. Matsen III, M.D.Chairman

research programs are underway in ourDepartment, a sampling of which arepresented in the pages that follow. Wehope you enjoy these articles. If youhave thoughts or questions, please besure to share them with me.

As this Research Reportdemonstrates, we have an inherentlycurious team of faculty, residents andstaff, all striving to improve the care ofour patients through a commitment torigorous investigation. With changes inreimbursement for health care and withchanges in the federal support forresearch, many orthopaedicdepartments across the country areprogressively curtailing theircommitment to research. Thanks to thededication of the UW Orthopaedicsand Sports Medicine faculty and to thegenerosity of the caring individuals inour region, our investigative programshave never been stronger.

-

2 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

Sigvard T. Hansen, Jr., M.D.2001 Distinguished Alumnus

University of Washington School of Medicine

Ted is generally creditedfor establishing the fieldof OrthopaedicTraumatology-the aggressiveand immediate fixation of allmajor fractures in multipleinjured individuals. Hisapproach enables severelytraumatized individuals to getout of bed soon after theiraccident, avoiding atelectasis,pneumonia, deep venousthrombosis, pulmonary emboli,urinary track infections, and bedsores. His philosophy andtechniques have saved vastnumbers of lives not only here,but also across the globe, thanksto his worldwide teaching effortsand to the traumatologyfellowships he has initiated here.

His attention is now turnedto foot and ankle reconstruction.Simply stated, he is the world’smost respected authority in thisfield. His fundamentalunderstanding of the alignmentand motion of the complex foot,subtalar, and ankle joints have enabledhim to master the most complex ofreconstructive problems, whether fromarthritis, injury, or degenerativeconditions such as Charcot MarieTooth’s disease. He now does more totalankle replacements than any otherindividual surgeon in the country. Aswas the case during his “traumatologyperiod”, his impact is not confined tothe patients he treats. He is in heavydemand as a lecturer across the worldand teaches students, residents, fellowsand practicing physicians from all overthe globe. Following him on rounds isa bit like being at the United Nations,with accents from Europe, Asia, Africaand, South America. His sentinel book,Functional Reconstruction of the Footand Ankle, was published in March2000. On July 20, 2000 the Sigvard T.Hansen Foot & Ankle Institute wasofficially opened at HarborviewMedical Center with Dr. Hansen as itsinaugural Director.

We should mention some of hismany other contributions to the

University of Washington. Hisconsistent presence at Harborview hasprovided the stamp of credibility onwhat used to be King County Hospital,helping convert it to one of the bestknown medical centers in the land.Thanks to his consistent leadership andstabilizing presence, HarborviewOrthopaedics is now ranked as the bestOrthopaedic program in the WesternUnited States and the best publicOrthopaedic program in the country!(see http://www.usnews.com/usnews/nycu/health/hosptl/specorth.htm)

He served the UW School ofMedicine as Chair of Orthopaedics forfive years and as acting Chair on twoother occasions. He served as Chief ofOrthopaedics at Harborview for manyyears. On two occasions when therewere massive defections of faculty, hesingle-handedly held the servicetogether. Thanks to the effect of his“deep keel”, the Orthopaedic service isnow in its longest period of facultystability and has the reputation of being

the best traumatology service inthe world.

Dr. Hansen’s excellence hasbeen recognized by patients,former residents, former fellows,fellow faculty, and industry in theestablishment of the Sigvard T.Hansen Endowed Chair forTraumatology Research. Thischair, of which he was theinaugural holder, providesperpetual support for innovativeresearch leading to improvedcare for injured individualsworldwide. In the near future wehope to have completed thefund-raising needed to endow anew Hansen Chair that will bepermanently directed toimproving the care of thoseindividuals with severe foot andankle arthritis and deformities.Those interested in knowingmore are invited to contact meat [email protected].

As a conclusion of our salute,we recognize that Ted Hansen isnot only the Distinguished

Alumnus of the University ofWashington School of Medicine, butalso the Distinguished Alumnus of theDepartment of Orthopaedics’Residency Program that he completedin 1969. I will always remember histhree admonitions:

• Stick your neck out for what youbelieve in.

• If it doesn’t look good, it probablyisn’t.

• If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doingright.

By the way, Ted, thanks for comingin at 3 am to help me with that tibiafracture 26 years ago and all the otherhelp you’ve given!

Best wishes,

Frederick A. Matsen III, M.D.Chairman

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 3

Rowing, cross-country running,or swimming competitively atthe college level requiresoutstanding aerobic fitness andextensive aerobic training. In all threesports, most of the training is sportspecific. While the cardiovascularchallenges for the three sports aresimilar, the musculoskeletal challengesvary significantly. Runners expose theirlower extremity bones and joints tolarge repetitive axial loads. Crewathletes expose their entire skeleton toboth axial and non-axial loads but byvirtue of their being seated, their lowerextremity bones and joints experiencelower axial loads than those of runners.Swimmers’ joints experience the leastcompressive force, and their bonesexperience the lowest axial loads.

Biological markers exist that canprovide an index of the rate of bone andcartilage turnover in a living human.Cross-linked N-telopeptides of type Icollagen (NTx) can be measured inblood or urine as an index ofosteoclastic bone resorption (Calvo etal., 1996). Cathepsin K, a proteaseabundantly expressed by osteoclasts,cleaves type I collagen to generate theNTx neoepitope (Atley et al., 2000).

NTx levels are elevated inpostmenopausal women, in patientswith metabolic bone disease and ingrowing children (Calvo et al., 1996).

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)have been implicated in the proteolyticdegradation of cartilage collagen, ahallmark of osteoarthritis. The cross-linked C-telopeptide of type II collagen(Col2CTx) assay measures a proteolyticneoepitope of MMP cleavage as amarker of cartilage degradation (Atleyet al., 1998). Higher levels of Col2CTxhave been demonstrated in growingchildren from growth plate degradationand in adults with rheumatoid arthritisand osteoarthritis, diseasescharacterized by the destruction ofarticular cartilage (Atley et al., 1998).

Although NTx and Col2CTx assayshave been applied to patients withskeletal pathologies, these assays havenot been used to assess healthy buthighly trained individuals in differentsports. This study evaluates NTx andCol2CTx levels in college athletes, allparticipating in high intensity aerobictraining, but experiencing verydifferent degrees of skeletal stress.

METHODSA cross-sectional study of sixty

collegiate athletes representing crew(C), cross-country runners (XC) andswimmers (S) was undertaken. Twentyathletes per training regimen, 10 malesand 10 females, volunteered toparticipate. Data were collected in theearly fall and during which time all ofthe athletes were in active training fortheir sports. Athletes were weighed andtheir height measured, then body massindex (BMI) was calculated. Spot urinesamples were collected and assayed forNTx (bone resorption) and Col2CTx(cartilage degradation) by competitionenzyme-linked immunosorbant assayson 96-well microtiter plates. The NTxand Col2CTx assays are based onmonoclonal antibodies that recognizespecific telopeptide sequences of type Iand type II collagen, respectively.Biomarker values were reported as aratio of urinary creatinine excretion.Data were analyzed by ANOVA and pairwise comparisons made by Tukey’s Testusing SigmaStat software.

RESULTSNTx control ranges comparisons

are gender specific while men andwoman are combined in the Col2CTxanalysis. Compared to controls, 70%of the rowers, 40% of the runners, and10% of the swimmers had NTx valuesmore than two standard deviationsabove the average.

Runners and rowers both hadsignificantly elevated NTx valuescompared to swimmers. For Col2CTx,swimmers and rowers did not differsignificantly from the controls, and onlyrunners were significantly elevated. Ageand urinary creatinine, variables whichmight affect the assay levels, did notvary significantly between the groups.Runners did have lower BMI thanswimmers or rowers.

DISCUSSIONThe data indicate significant

differences in bone remodeling andcartilage degradation between the threesports. High NTx levels are consistentwith increased bone remodeling. With

Assessment of NTx and Col2CTx Urine Assay in EnduranceAthletesJOHN O’KANE, M.D., LYNNE ATLEY, PH.D., CHRIS HAWLEY, M.D., CAROL TEITZ, M.D.,AND DAVID EYRE, PH.D.

Figure 1: Crew.

-

4 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

remodeling the potential exists for netbone loss or gain depending on therelative activity of osteoclasts(resorption) and osteoblasts(formation). An increase in boneremodeling in response to trainingmost likely reflects an adaptive responseof the skeleton to the stresses andstrains applied to it. Many studies havereported a positive association betweenload-bearing exercise and bone mineraldensity. The Col2CTx assay is clinicallyless well studied, but elevations appearto be secondary to cartilagedegradation, either from active growth

plate degradation in children or inadults with rheumatoid orosteoarthritis.

In our study groups, crew NTxvalues are the highest, likely secondaryto axial and non-axial forces applied tothe entire skeleton. Runners have highvalues as well compared to the generalpopulation secondary to high-impactloading of the lower skeleton despitelittle stress to the upper body.Swimming clearly stresses the entirebody, but apparently through forcesresulting in significantly less boneremodeling.

One might postulate that theCol2CTx data would parallel the NTx .Interestingly though, the Col2CTx datasuggest that while swimming minimallystresses the joints as well as the bones,rowing which has the highest NTxvalue, causes significantly less cartilagedegradation than running. Running isalso the only sport with a Col2CTxvalue significantly elevated overcontrols. There is some evidence thatprofessional participation in runningsports such as soccer can result in earlyOA changes to weight-bearing joints,but the influence of injury versus jointloading alone is hard to separate. Oncearticular cartilage is injured, continuedloading can result in more rapidprogression of degenerative changes.Clinical studies are mixed regarding therisk of developing osteoarthritis fromlong term participation in regularexercise with some studies suggesting amodest increased risk (Lane et al, 1999).In Lane’s study weight-bearing exercisewas not any more likely than otherforms of exercise to cause changes. Ourdata suggests that distance runners arestressing their joints sufficiently tocause cartilage degradation beyond thatseen in the other sports, but clinicalstudies do not suggest runners are atsignificant increased risk for prematureOA provided they do not have pre-existing knee injuries.

These results may have implicationsfor exercise counseling. There is ampleevidence that aerobic exercise isimportant for disease prevention,improving longevity and quality of life.One disease positively affected byexercise is osteoporosis; a debilitatingage related loss of bone densityresulting in crippling deformity and lifethreatening fractures. Weight-bearingexercise is specifically recommended toprevent osteoporosis because it isknown to stimulate bone turnover witha net increase in bone density. It iscommon though for elderly individualsto have arthritis of their weight-bearingjoints making weight-bearing exercisedifficult and high impact exercisecontraindicated. These results suggestthat for this population, rowing may bean ideal exercise, stimulating boneturnover with less stress to weight-bearing joints. Whether or not rowingmaintains bone density to the sameextent as walking, jogging, or runningshould be the subject of future research.

Figure 2: Cross Country Running.

Figure 3: Swimming.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 5

RECOMMENDED READING

Atley LM, Shao P, Ochs V, Shaffer K,Eyre DR. 1998.Matrixmetalloproteinase-mediatedrelease of immunoreactive telopeptidesfrom cartilage type II collagen. Trans.Orthop. Res. Soc. 23:850.

Atley LM, Mort JS, Lalumiere M, EyreDR. 2000. Proteolysis of human bonecollagen by cathepsin K:Characterization of the cleavage sitesgenerating the cross-linked N-telopeptide neoepitope. Bone 26:241-247.

Calvo MS, Eyre DR, Gundberg CM.1996. Molecular basis and clinicalapplication of biological markers ofbone turnover. Endocrine reviews17:333-368.

Lane NE et al. 1999. Recreationalphysical activity and the risk ofosteoarthritis of the hip in elderlywomen. Journal of Rheumatology. 26:849-54.

Larsen E, Jensen PK, Jensen PR. 1999.Long-term outcome of knee and ankleinjuries in elite football. Scand J MedSci Sports. 9(5): 285-9.

Table 1: Assessment data table.

Age BMI NTx Col2CTx Creatininey r s kg /m2 nM BCE/mM Cr ng/mg Cr nM

Cross Country 19.3 +/- 1.3 21.3 +/- 1.9 61.9 +/- 31.0 35.1 +/- 14.5 11.6 +/- 8.3Swimming 19.4 +/-1.6 25.9 +/-2.7 38.8 +/- 22.7 19.0 +/- 7.8 12.7 +/- 5.6Crew 19.8 +/- 1.0 26.6 +/-2.7 85.8 +/-35.7 26.5 +/- 7.8 13.7 +/- 4.9Control Women 3 6 35 +/- 15Control Men 4 6 27 +/- 12Control 3 3 24.5 +/- 8.4

-

6 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

M atrilin-3 is a recentlyidentified matrix protein ofcartilage that showssequence homology to matrilin-1(cartilage matrix protein or CMP).Matrilin-1 and -3 are both prominentlyexpressed within growth cartilagematrix. They have several molecularfeatures in common including asignalling peptide, either one or twovon Willebrand factor type A-likedomain(s), one or more EGF-likedomain(s), and a COOH-terminalcoiled-coil (-helix. Matrilin-1 consistsof two vWFA-like modules connectedby one EGF-like domain, whereasmatrilin-3 cDNA predicts a singlevWFA-like module separated from theC-terminal coiled-coil by four EGF-likemodules (Fig. 1). We recently reportedthe identification of matrilin-3 at theprotein level in extracts of bovine andhuman growth cartilages. The findingsestablished that matrilin-3 is a subunitwith matrilin-1 in disulfide-bondedheterotetrameric molecules. Usingspecific antibodies to human matrilin-1 and -3, we here define further themolecular properties of matrilin-3 inhuman fetal cartilage and demonstratethe presence of matrilin-3, but notmatrilin-1, in normal adult humanarticular cartilage.

MATERIALS AND METHODSCartilage slices from fetal human

epiphyseal cartilage (humerus andfemur, 96-122 days, medicalterminations, Central Laboratories forHuman Embryology, University ofWashington, Seattle) and adult humanarticular cartilage (banked normal

tissue from a male donor 25 yr of age,Northwest Tissue Center, Seattle) weredigested with chondroitinase ABC.Extracted proteins were resolved bySDS-PAGE and transblotted to PVDFmembrane for Western blot analysis.Western blot analysis was performedwith two polyclonal antisera. One wasgenerated in rabbits against a mixtureof two synthetic peptides, matchingsequences in the A1 domain(-EAGAREPSSNIPKV-) and thecarboxy-terminal domain(-LEKLKINEYGQIHR-) of the humanmatrilin-3 cDNA translation product.The polyclonal antiserum againstmatrilin-1 was made similarly againsta mixture of two synthetic peptides(-AEGGRSRSPDISKV-) and(-AVSKRLAILENTVV-), also from A1and carboxy-terminal domains.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONElectrophoresis of the disulfide-

bonded matrilin tetramers from fetalcartilage on a low percentagepolyacrylamide gel (SDS-5%PAGE)resolved a series of bands that wereimmunoreactive for matrilin-3 (Fig. 2,lane 2). The faster migrating of thesebands also reacted with matrilin-1antibody (Fig. 2, lane 1). Fetal growthcartilage therefore contains a mixtureof molecular forms of mat-1/mat-3heterotetramers. An extra bandmigrating slower than the mat-1/mat-3 heterotetramers reacted for matrilin-3 only, suggesting the presence of thehomotetrameric molecule of matrilin-3. Therefore, fetal growth cartilagecontains homotrimeric molecules of

matrilin-1, homotetrameric moleculesof matrilin-3 and the variousheterotetrameric chain combinationsof matrilins-1 and -3. Western blotanalysis of matrix proteins extractedfrom adult articular cartilage showed adisulfide-bonded high molecularweight band migrating slower than themat-1/mat-3 tetramers, reacting withthe matrilin-3 antibody but not thematrilin-1 antibody and running in theposition of the homotetramericmolecule of matrilin-3 from fetalcartilage (Fig 2, lane 4). At the proteinlevel, it has previously been shown thatboth matrilin-1 and matrilin-3 areprominent matrix components ofbovine and human epiphyseal growthcartilages but not of adult articularcartilage. By developing specificantisera to the individual subunits wewere able to further characterize themixture of molecular forms of thematrilin-1/matrilin-3 complex ingrowth cartilage and demonstrate thatnormal adult articular cartilage isdistinct in containing the matrilin-3homotetramer. Matrilin-1 is known tobind to type II collagen fibrils and toaggrecan and also to form a filamentouspolymer by self interaction. Thefunction of matrilin-3 is unknown butits content of a single vWFA-likedomain and multiple EGF-likedomains and difference in pattern oftissue expression suggests that matrilin-3 will differ from matrilin-1 in itsinteractive properties in the matrix. Itsdistribution, changes with age andpotential effects on its expression injoints undergoing osteoarthritic

Identification of Matrilin-3 in Adult Human Articular Cartilage

JIANN-JIU WU, PH.D. AND DAVID EYRE, PH.D.

Figure 1: Modular structures of matrilin-1 and matrilin-3 monomers.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 7

changes will be important to define.

RECOMMENDED READING

Wu, J. J., and Eyre, D. R. (1998).Matrilin-3 forms disulfide-linkedoligomers with matrilin-1 in bovineepiphyseal cartilage. J Biol Chem 273,17433-17438.

Belluoccio, D., Schenker, T., Baici, A.,and Trueb, B. (1998). Characterizationof human matrilin-3 (MATN3).Genomics 53, 391-394.

Wagener, R., Kobbe, B., and Paulsson,M. (1997). Primary structure ofmatrilin-3, a new member of a familyof extracellular matrix proteins relatedto cartilage matrix protein (matrilin-1)and von Willebrand factor. FEBS Lett413, 129-134

Chen, Q., Johnson, D. M.,Haudenschild, D. R., Tondravi, M. M.and Goetinck, P. F. (1995) Cartilagematrix protein forms a type II collagen-independent filamentousnetwork:Analysis in primary cellcultures with retrovirus expressionsystem. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1743-1753.

Paulsson, M. and Heinegard, D. (1982)Radioimmunoassay of the 148-kilodalton cartilage protein.Distribution of the protein amongbovine tissues. Biochem. J. 207, 207-213.

Figure 2: Western blot analysis of matrilin-1/matrilin-3 oligomers extracted from fetal human epiphysealcartilage (lanes 1 and 2) and adult human articular cartilage (lanes 3 and 4) Matrilin samples were rununder non-reducing conditions on SDS-5% PAGE then blotted to PVDF membrane and developedwith the anti-matrilin-1 (lanes1 and 3) and anti-matrilin-3 (lanes 2 and 4) sera.

-

8 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

Liposarcomas are the second mostcommon diagnosed malignantsoft tissue sarcoma. The clinicalmanagement of liposarcomas isprimarily surgical. High gradeliposarcomas occasionally lead tometastatic disease and death as there isno proven effective systemic treatment.A better understanding of the basicbiology of these sarcomas is essential ifbetter treatments are to be developed.

The molecular mechanisms thatpermit normal fat cells to undergomalignant differentiation are unknown.Chromosomal translocations are acommon feature of malignancy.Translocations often result in theformation of novel fusion genes, andthereby fusion proteins, that in some

manner alter the normal function of thehost cell. Several sarcomas are thoughtto arise as a direct result of atranslocation resulting in expression ofa fusion protein. Human myxoidliposarcomas consistently have acharacteristic chromosomaltranslocation, t(12;16)(q13;p11)(Figure 1). This translocation creates afusion gene consisting of a DNAsequence encoding a portion of thegene TLS (translocated in liposarcoma)and the gene CHOP, a member of theC/EBP family of regulatorytranscription factors. Our currentstudy addresses the mechanism bywhich this fusion gene (protein), TLS/CHOP, contributes to malignanttransformation of normal lipocytes.

The N-terminal domain of thenative TLS protein has been shown toassociate with RNA polymerase II (PolII); the C-terminal domain of TLSinteracts with several members of afamily of proteins (splicing factors) thatmediate RNA splicing. Thus TLS isbelieved to function as a molecule thatspatially and temporally links theprocesses of transcription and splicing.In myxoid liposarcoma the fusionpartner of TLS, in this case CHOP,replaces the C-terminal domain ofnormal TLS. YB-1 is an evolutionarilyconserved protein involved intranscription and translation. Earlierwork in our laboratory suggested thatYB-1 also interacted with the C-terminal domain of TLS in a mannersimilar to splicing factors. Ourhypothesis was that the fusion proteinTLS/CHOP, missing the normal intactC-terminal domain of TLS, would notbind YB-1 thus resulting in aberrantsplicing of messenger RNA (mRNA).

RESULTSImmunoprecipitation and Western

analysis of lysates from transfectedCOS-7 cells were used to determinewhether the TLS/CHOP fusion proteincan bind to RNA Pol II and to theputative RNA splicing factor YB-1. Thecells were transfected with a series ofplasmids containing gene insertsencoding either TLS, TLS-CHOP, orCHOP. Our results show that nativeTLS and the fusion protein TLS/CHOPboth associate with RNA Pol II (Figure2). Further, our assays showed thatbinding of TLS to YB-1 is dependentupon the C-terminal domain of TLS.Native TLS was shown to co-immunoprecipitate with the splicingfactor YB-1. YB-1 and TLS/CHOP didnot co-immunoprecipitate, consistentwith our hypothesis that the fusionprotein TLS/CHOP is unable to bindto YB-1 due to substitution of the C-terminal domain of TLS by CHOP(Figure 3).

Although our immunoprecipitationassays show that TLS/CHOP interactswith RNA Pol II and not with YB-1, wefurther needed to analyze whether thisobservation has any effect on RNA

TLS / CHOP Inhibits RNA Splicing Mediated by YB-1

TIMOTHY RAPP, M.D., LIU YANG, PH.D., ERNEST U. CONRAD III, M.D., AND HOWARD A. CHANSKY, M.D.

Figure 1: Human myxoid liposarcomas have a characteristic chromosomal transloccation, t(12;16)that results in fusion of the amino terminal domain of TLS to CHOP. The fused CHOP gene includessome DNA from the 5' untranslated region. TLS/CHOP is shorter than TLS but runs more slowly ona gel due to changes in conformation and charge. DNA-BD = DNA binding domain; RNA-BD =RNA binding domain.

Figure 2: COS-7 cells transfected with either Flag-tagged TLS, TLS/CHOP, or CHOP (lanes 1-3) wereused for immunoprecipitation with the anti-RNA Pol II followed by blotting with either anti-Flag or anti-RNA Pol II. RNA Pol II binds to TLS (lane 4) and to TLS/CHOP (lane 6) but not to CHOP (lane 5). Theasterisk indicates the position of the anti-RNA Pol II antibody.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 9

splicing. To evaluate the effect that TLS/CHOP has on YB-1-mediated RNAsplicing, we performed reverse-transcriptase polymerase chainreaction (RT-PCR) and RNaseprotection assay. Alternative splicing ofthe adenovirus E1A pre-mRNAnormally resulted in the generation ofthree different splicing isoforms. YB-1expression increased the 13S isoform inour assay. While co-expression of TLSor CHOP did not alter YB-1-mediatedsplicing pattern of E1A mRNA, TLS/CHOP expression inhibited thissplicing effect of YB-1 (results notshown).

DISCUSSIONThe chimeric fusion protein TLS/

CHOP is a hallmark of the mostcommon subtype of liposarcoma.However, little is known about theeffects this translocation has on thebiology and pathogenesis ofliposarcomas. Our studies focused onimportant molecular mechanisms thatmay be altered by the creation of thisnovel fusion protein.

RNA Pol II is the crucial enzymeresponsible for the transcription andprocessing of mRNA from the DNAtemplate. The results of ourimmunoprecipation studies indicatethat wild-type protein TLS, and thefusion protein TLS/CHOP that ispresent in myxoid liposarcoma cells,retain the ability to bind RNA Pol II.

However, TLS/CHOP loses its affinityfor YB-1, a transcriptional modifier andsplicing factor. We presume that theinteraction of native TLS with RNA PolII and YB-1 is crucial for the normalfunctioning of the RNA Pol II enzyme.Though TLS/CHOP preserves itsinteraction with RNA Pol II, it ispossible that the replacement of the C-terminus of wild-type TLS with CHOPinterferes with normal RNA processingand splicing.

RT-PCR and the RNase protectionassay (RPA) are very sensitivetechniques that permit identificationand quantification of very smallamounts of RNA. Our RT-PCR andRPA experiments further support thehypothesis that RNA processing isaffected by the fusion gene TLS/CHOP.Our results show that splicing of E1ARNA is inhibited in cells transfectedwith TLS/CHOP when compared tocells transfected with native TLS.

These results advance ourunderstanding of sarcoma biology inseveral ways. The fusion gene TLS/CHOP cannot bind to the splicingfactor YB-1 and in our in vivo assays,this has marked effects on splicing ofmRNA. Aberrant splicing and alteredprotein expression are general featuresof tumors and this may be one of themechanisms by which they occur. Wehave published similar findings for afusion gene found in Ewing’s sarcomatissue (EWS/Fli-1); our experiments

suggest that disruption of RNA splicingmay be an important generalizedfeature of sarcomas with fusionproteins.

RECOMMENDED READING

Yang L, Embree LJ, Tsai S, HicksteinDD: Oncoprotein TLS interacts withserine-arginine proteins involved inRNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 1998 Oct23;273(43):27761-4.

Hisaoka M, Tsuji S, Morimitsu Y,Hashimoto H, Shimajiri S, Komiya S,Ushijima M.: Detection of TLS/FUS-CHOP fusion transcripts in myxoidand round cell liposarcomas by nestedreverse transcription-polymerase chainreaction using archival paraffin-embedded tissues. Diagn Mol Pathol.1998 Apr;7(2):96-101.

Ron D.: TLS-CHOP and the role ofRNA-binding proteins in oncogenictransformation. Curr Top MicrobiolImmunol. 1997 220:131-42. Review.

Crozat A, Aman P, Mandahl N, Ron D.:Fusion of CHOP to a novel RNA-binding protein in human myxoidliposarcoma. Nature. 1993 Jun17;363(6430):640-4.

Figure 3: COS-7 cell lysates expressing Myc-tagged YB-1 and either Flag-tagged TLS, TLS/CHOP,or CHOP (lanes 1-3) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc. Blotting was then performed witheither anti-Myc or anti-Flag. YB-1binds to TLS (lane 4) but does not bind to either TLS/CHOP orCHOP (lanes 5 and 6). The bottom gel is a control to ensure that the proteins were expressed atcomparable levels. The asterisk indicates position of the anti-myc antibody used in theimmunoprecipitation.

-

10 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

Animal studies suggest that step-offs created by displacement ofosteochondral fragments canremodel. However, the mechanism bywhich remodeling occurs is unknown,and large incongruities seldom, if ever,heal completely. This issue complicatesthe surgical technique of osteochondralautografting — so-called“mosaicplasty” — because cylindricalplugs do not lend themselves to exactarticular reconstruction of traumaticdefects. Mosaicplasty, which is arelatively new procedure, is gainingwidespread popularity for thetreatment of focal chondral andosteochondral defects. It entails

harvesting one or multiple plugs fromeither the periphery of the distalfemoral articular surface or theintercondylar notch. Surprisingly, thebasic science literature onosteochondral autografts is quitelimited. Many questions remainregarding the viability and remodelingpotential of the articular cartilagepresent on these cylindrical autografts.In this study, we asked whether thinarticular cartilage on grafts harvestedfrom the joint periphery could enlargeto reduce and/or eliminateincongruities created when a graft wascountersunk.

METHODSFollowing guidelines of our IACUC

and under adequate anesthesia, medialparapatellar arthrotomy and partial fatpad resection were performed to allowfor collection of fresh osteochondralplugs 5mm in diameter from the medialtrochlear facet of skeletally mature malesheep. A trephine drill bit was utilizedto harvest the autografts, which wereimmediately transplanted intomatching drill holes in the ipsilateralmedial femoral condyles. In threeanimals the periphery of the autograftsurface was placed flush with thesurrounding cartilage (Group I). Inthree others countersinking exceeded1.5 mm (Group II), and in three sheepthe surface was countersunkapproximately 1mm (Group III).Initial congruity/incongruity of thesurface was assessed with a silicone cast(Aquasil, Dentsply, Milford, DE) madeintraoperatively. As markers of boneformation, the sheep received aninjection of oxy-tetracyclineperioperatively, and calcein or oxy-tetracycline at two and four weeks post-operatively. Immediate ad lib activitywas permitted.

RESULTSOn the basis of high-resolution

microscopy and fluorescent markers, allgrafts had rapidly revascularized at sixweeks. Viable osteocytes were presentthroughout the grafted bone. Bloodvessels and foci of new bone formationwere present in all areas, including thesubchondral region. The appearanceof the cartilage and subchondral platedepended on the level at which the graftwas placed.

Group I: Grafts fitted flush with thesurrounding cartilage surface showedlittle change in the structure of thearticular cartilage. The grafted cartilageunderwent limited enlargement toassume a slight convexity that matchedthe contour of the surrounding medialfemoral condyle. With the numbersavailable, this enlargement was notstatistically significant (p=0.78).Proteoglycan staining of the articularcartilage in this group matched both the

Depth of Countersinking Modulates Cartilage Remodeling inSheep Osteochondral AutograftsFRED HUANG, M.D., PETER T. SIMONIAN, M.D., ANTHONY NORMAN, B.S.E.,AND JOHN CLARK, M.D., PH.D.

Figure 1: Specimen countersunk approximately two millimeters shows differential matrix staining ofthe grafted cartilage (g) in comparison to the recipient site cartilage (f). The tidemarks (tm) are linearand have not duplicated or advanced. The grafted cartilage has not enlarged. Magnification 25X.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 11

surrounding cartilage and controlcartilage samples. In comparison tointact samples from the donor site, thetidemark was slightly irregular, butthere was no evidence of tidemarkdissolution or duplication. No layer ofthe grafted cartilage exhibitedchondrocyte hyperplasia or cloning.

Group II: Cartilage on plugscountersunk 1.5 mm or more appearedto be dormant despite vascularity in theadjacent subchondral region. In onecase complete chondrolysis occurred.In the remaining two specimens in thisgroup, the cartilage did not swell,chondrocyte nuclei were often

pyknotic, and proteoglycan stainingwas less intense compared to the othergroups. The architecture of thetidemark remained unchanged fromthe pre-transplant configuration.Vessels invaded the graft, but followedno consistent pattern and were notassociated with chondrocytehyperplasia. The grafted cartilagesurface was irregular and overgrownwith fibrous tissue.

Group III: Through hypertrophyand hyperplasia, the central cartilage ongrafts that had been countersunkapproximately 1 mm grew to match thepre-existing surface level. The averagecartilage thickness (versus controls)increased by 55% (p=0.046). Multipletidemarks were visible, and the zone ofcalcified cartilage was wide andindistinct. The cellularity of the deepestlayers increased, and many of thehyperplastic chondrocytes wereorganized in individual cell strings(chondrones). Vertically-orientedcapillaries penetrated into the basallayer of the cartilage, following theplane of the chondrones in a patternreminiscent of endochondralossification in a physis. New bone waspresent along the path of thesecapillaries.

DISCUSSIONThis is the first description of a

remodeling process in malreducedosteochondral fragments. Cartilage ongrafts sunk below a critical levelbecomes quiescent, whereas cartilageplaced in a minimally countersunkenvironment remodels impressively.This remodeling occurs via a processthat closely resembles endochondralossification, in that it involveschondrocyte hyperplasia andhypertrophy, invasion of capillariesfrom the subchondral bone, and newbone formation. It is not clear why thecartilage on deeply countersunk graftsbecomes atrophic, but its failure toremodel suggests that some minimumamount of loading is necessary tomaintain metabolic activity of articularcartilage in cylindrical autografts.

Clinical Relevance: Osteochondralautografting is an attractive restorativeprocedure for the treatment of focalchondral and osteochondral defects.One of the difficulties that surgeonsface when performing this procedureis the imperfect match between thesurface contours of grafts and the areas

Figure 2: Graft countersunk one millimeter demonstrates significant cartilage growth centrally (g).Recipient site cartilage (f) has deformed to create an overlapping rim at the periphery of the graft.The tidemark of the graft has advanced centrally but not peripherally (tm). Magnification 25X.

Figure 3: Higher power view shows a wide layer of calcified cartilage (cc) with adjacent chondrones(h) and neo-vascularity (v). Mature bone is present in the deeper layers (b). Magnification 400X.

-

12 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

to be grafted. It is unclear if graftsshould be placed slightly proud, flush,or slightly countersunk to yield optimalclinical results. Based on the results ofthis pilot study, we recommend thatgrafts be inserted either flush or slightlycountersunk, but not countersunkmore than the thickness of thesurrounding cartilage. Deeplycountersunk grafts should be avoidedfor fear of cartilage atrophy due toinsufficient mechanical loading. Whencountersunk minimally, graftedarticular cartilage exhibits significantremodeling and growth via a processthat mimics the endochondralossification associated with a physis.Such cartilage growth increases thethickness of the grafted cartilage andminimizes surface incongruities thatare created by plug countersinking and/or the inherent mismatch betweengrafts and the sites to be grafted. Thesefindings are relevant to otherconditions that produce acute articularincongruities, namely intra-articularfractures.

RECOMMENDED READING

Kish, G.; Modis, L.; and Hangody, L.:Osteochondral mosaicplasty for thetreatment of focal chondral andosteochondral lesions of the knee andtalus in the athlete. Rationale,indications, techniques, and results.Clin. Sports Med., 18(1): 45-66, 1999.

Lefkoe, T.; Walsh, W.; Anastasatos, J.;Ehrlich, M.; and Barrach, H.:Remodeling of articular step-offs. Isosteoarthrosis dependent on defectsize? Clin. Orthop. 314: 253-265, 1995.

Llinas, A.; McKellop, H.; Marshall, G.;Sharpe, F.; Kirchen, M.; and Sarmiento,A.: Healing and remodeling of articularincongruities in a rabbit fracture model.J. Bone Joint Surg Am. 75(10): 1508-1523, 1993.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 13

R econstruction of themultiligament knee injury orknee dislocation frequentlyrequires a combination of ligamentrepair, augmentation andreconstruction. Our experience withreconstruction and augmentation ofcombined medial collateral ligament(MCL), lateral collateral ligament(LCL) and anterior cruciate ligament(ACL) injuries suggests the spaceavailable for graft fixation in the distalfemur is limited by the multi-planarirregular surfaces of the distal femurand the requirement for multiplescrews or tunnels. Posterior cruciateligament reconstruction is oftenperformed as well in this setting, yet dueto the medial femoral condyle locationof the usual PCL tunnel(s) this graftdoes not create a logistical problem.

The optimal placement of the ACLfemoral tunnel is well defined.Subsequent screws or tunnels for LCLand MCL grafts or augmentations mustavoid the ACL tunnel. If one limits drillpassage or tunnel depth to the widthof the condyle, then avoidance of the

ACL graft or tunnel is not an issue.However for greater screw purchase ortunnel length and interference fixation,we frequently drill beyond the midlineof the distal femur, thus threateningencroachment on the ACL graft. We arecurrently using more tunnel fixationthan washered screw and post fixationfor many of our collateral repairs andreconstructions as many patients havecomplaints regarding the prominenceof the washered screws at the level ofthe epicondyles. It is clear fromclinical and anatomic studies that drillpaths perpendicular to the distal femurfrom either epicondyle (collateralorigins) will enter 1) the femoral notchand pierce the ACL graft or 2) thefemoral tunnel and potentiallycompromise ACL fixation. Thisinvestigation was designed to definesafe screw and tunnel placement in thedistal femur for multiligamentreconstruction.

METHODSA three dimensional model of the

distal femur was created using

Distal Femoral Tunnel Placement for Multiple LigamentReconstruction: Three Dimensional Computer Modeling andCadaveric Correlation

transverse computed tomographic(CT) images from a 28 year old female.Digital 1 mm image slices (DICOMformat) were transferred from the CTworkstation (HighSpeed Advantage CT,General Electric Medical Systems,Milwaukee, WI) to a personal desktopcomputer (PowerMacintosh, AppleComputer Company, Cupertino, CA)for model generation. Segmentation ofthe 2-D model geometry wasperformed using digital imageprocessing and analysis software (NIHImage, US National Institutes of Health,Bethesda, MD) with the aid of custommacros. The segmented files wereimported into a 3-D computer aideddesign (CAD) environment (Formoz,Autodessys Inc.), Columbus, OH)where the model was meshed andinvestigated. A standard 10 mm ACLfemoral tunnel was incorporated intothe 3-D model, preserving a typical 1mm posterior wall. A 7 mm diameterlateral epicondyle tunnel (that mostcommonly used by us clinically) wasincorporated into the model, as was a10 mm diameter medial epicondyletunnel. Optimal tunnel placement wasinvestigated by digitally insertingpotential MCL and LCL tunnels aroundan existing ACL tunnel with the goal ofdefining tunnel locations andtrajectories that did not overlap oneanother or penetrate the articularsurfaces of the distal femur. Thelimiting landmarks for tunnelplacement was the anatomic origin ofthe collateral ligaments at the femoralepicondyles. Based on this computermodel, safe tunnels trajectories weredefined.

To assess the accuracy of the 3-D CTmodeling ACL, MCL and LCL tunnelswere then created in 3 different cadaverknees rigidly mounted allowing kneemanipulation. Standard arthroscopicinstruments were used to create a 10mm diameter femoral ACL tunnel 30mm deep retaining one mm of femoralnotch back wall. Forty (40) mm lengthlateral (7mm diameter) and medial (10mm diameter) epicondylar tunnels

WILLIAM J. MILLS, M.D. AND RANDY P. CHING, PH.D.

Figure 1: CT model demonstrating “safe” ACL, MCL, and LCL trajectories in the coronal plane.

MCL tunnel LCLtunnel

ACLtunnel

-

14 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

were created over guide wires placed atangles defined by the CT model. Afterdrilling the initial tunnels, all tunneldiameters were sequentially expanded1 mm until tunnel overlap occurred.

RESULTSThe 3-D computer generated model

defined “safe” LCL or lateralepicondylar tunnels as those angled 30º

anteriorly and 10º distally (Figures 1and 2). Flatter trajectories, or thosenot angled distally entered either thefemoral notch or the ACL graft. Thiswas readily confirmed by the cadaverdissection (Figure 3). Greater anterior

or distal angulation encroached on thefemoral trochlea. MCL or medialepicondylar tunnels were “safe” ifangled 20º anteriorly with 10º proximalangulation (Figures 1 and 2). Greaterproximal angulation of the MCL tunnelcaused cut-out of the cortex proximalto the medial epicondyle especially aslarger diameter tunnels were created.10 mm tunnels based on this modelavoided violating articular surfaces inall cadaver specimens. Increasing theACL tunnel diameter to 12 mmproduced no encroachment on eitherthe LCL or MCL tunnel. Increasing thediameter of the MCL tunnel to 11 mmcreated MCL/LCL tunnel overlap in themidline of the femur in one cadaver,while a 12 mm MCL tunnel and 11 mmLCL tunnel created overlap in themidline in the remaining two cadavers(Figure 4).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS The 3-D CAD model accurately

predicted safe tunnel placements in thedistal femur when applied to cadaverspecimens. There is greater freedom forACL than MCL or LCL tunnel diameter.Fairly straightforward trajectorycorrections (LCL: 30º anterior, 10º

distal; MCL: 20º anterior, 10º proximal)from both epicondyles should allowsafe drill paths and tunnel creation inthe distal femur. Cross sectioning ofthe cadaver specimens suggests thatcollateral tunnels greater than 10 mmdiameter, in order to avoid the ACLgraft and the articular surface, willeventually converge when crossing themidline. We have incorporated thisinformation in clinical practice, andhave had no apparent instances oftunnel encroachment, femoral notch orarticular surface violation in our patientpopulation. The 3-D CAD model mayprove useful in other areas where non-linear anatomy and limited space forfixation provide surgical challenges.

RECOMMENDED READING

Fineberg MS, Zarins B, Sherman OH.Practical considerations in anteriorcruciate ligament replacement surgery.Arthroscopy 2000 16(7): 715-24.

Figure 2: CT model demonstrating “safe” ACL, MCL, and LCL trajectories in the sagittal plane.

Figure 3: Guide-wire or drill for LCL graft fixation perpendicular to the long axis of the femur.

Perpendicular lateral

guide-wire violating

ACL tunnel

MCL tunnel(10 mm)

ACLtunnel(10 mm)

LCL tunnel(7 mm)

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 15

Sommer C, Friedrich NF, Muller W.Improperly placed anterior cruciateligament grafts: correlation betweenradiological parameters and clinicalresults. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc 2000 8(4): 207-13.

Veltri DM and Warren RF. Operativetreatment of posterolateral instabilityof the knee. Clin Sports Med 199413(3): 599-614.

Figure 4: Cadaveric sagittal cross-section.

ACL

L CL

MCL tunnel

3 mm

5 mm

-

16 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

The optimal treatment of distaltibial metaphyseal fracturesremains controversial. Whileintramedullary nailing has gainedacceptance as a method of stabilizationof diaphyseal tibia fractures, its use hasnot become widely accepted for distalmetaphyseal fractures. Fixation with anintrameduallary device spares theextaosseous blood supply, allows forload-sharing, avoids extensive softtissue dissection, and is a techniquefamiliar to most surgeons. Recentadvances in the design ofintramedullary nails have extended thespectrum of fractures amenable to thisfixation. The purpose of this study wasto evaluate reamed intramedullarynailing of distal tibial metaphysealfractures located within fivecentimeters of the ankle joint.

MATERIALS AND METHODSDuring a sixteen months period,

243 skeletally mature patients with tibiafractures were treated withintramedullary nailing at twoinstitutions. Thirty-six patients withinvolvement of the distal fivecentimeters of the tibia and were treated

with reamed intramedullary nailingand formed the study group. Therewere 24 male and 12 female patients,ranging in age from 18 to 82 years(mean 30 years). These tibial fractureswere classified according to AO/OTAguidelines as 43A1 (n=8), 43A2 (n=5),43A3 (n=13), 43C1 (n=6), 43C2 (n=2),and 43C3 (n=2). Fourteen fractures(39%) were open. An associatedfracture of the fibula was present in 35of 36 patients. Four patients had aconcomitant leg compartmentalsyndrome and were treated with fourcompartment fasciotomies.

The ten 43C fractures (28%) witharticular extensions were treated withsupplementary percutaneous fixationsprior to intramedullary nailings (Figure1). Fibular fractures felt to have aneffect on ankle joint or distaltibiofibular syndesmosis stability weretreated with open reduction andinternal fixation prior tointramedullary nailing. The tibialfractures were treated with reamedintramedullary nailing systems thatoptimize distal fixation, allowingplacement three biplanar distalinterlocking screws through the distal

three centimeters of the nail. Theprimary reduction aid for obtaininglength, alignment and rotation of thedistal tibial segment was fibular platingin 19 patients (54%). Additionalreduction techniques included use of afemoral distractor, temporarypercutaneous clamp fixation,percutaneous manipulation withSchantz pins, and open reduction andtemporary unicortical tibial plating.The surgical goals of obtaining andmaintaining anatomical alignmentduring nailing was furtheraccomplished with central placementof the guide wire and all reamers, andmaintenance of the reduction at thetime of nail passage.

In order to evaluate the functionaloutcome and health status of this groupof patients, we administered the Short-Form 36 (SF-36), a generic health statusmeasure and the MusculoskeletalFunction Assessment (MFA), afunctional outcome measure.

RESULTSThe average distance from the distal

extent of the tibial fracture to theplafond was 35 millimeters (range 0 to45 mm). The average distance betweenthe distal nail tip and the articularsurface of the plafond was 6.2 mm(range 2 - 10 mm). The average sagittalplane deformity was 0.9 degrees (range0 - 5 degrees). The average coronalplane deformity was 0.3 degrees (range0 - 5 degrees). Acceptable alignmentwas obtained in 33 patients (92%) andno patient had a malalignment ofgreater than five degrees. Two patientshad a five degree recurvatum deformityand one patient had a five degree valgusdeformity.

Of the thirty-six patients in ourstudy, radiographic follow-up to unionwas obtained in thirty patients. Fivepatients were lost to follow-up and onepatient died on postoperative daynumber three from pulmonarycomplications. Three patients withopen fractures with associated bone lossrequired staged iliac crest autograft atan average of 6.7 weeks (range, 6 - 8weeks) postoperatively. Four patientsunderwent dynamization of their nail

Intramedullary Nailing of Distal Metaphyseal Tibial FracturesSEAN E. NORK, M.D., ALEXANDRA K. SCHMITT, M.D., JULIE AGEL, M.A., SARAH K. HOLT, M.P.H.,JASON L. SCHRICK, B.S., AND ROBERT A. WINQUIST, M.D.

Study Population Normative ValuesCategory

Avg SD Avg SD

p-value

Physical Function 65.0 31.6 83.5 23.5 0.007

Role Limitations Physical 61.8 41.8 83.1 32.3 0.02

Bodily Pain 66.2 28.3 77.4 24.5 0.03

General Health 70.4 29.6 71.4 20.3 0.87

Vitality 57.9 34.8 62.7 21.9 0.45

Social Functioning 81.3 18.8 87.0 21.7 0.37

Role Limitations Emotional 90.9 30.2 86.2 30.3 0.59

Mental Health 74.4 18.4 76.5 18.8 0.99

Table 1: Comparison of Study Population and SF-36 Normative Values.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 17

at three months postoperatively toencourage healing.

In these thirty patients, there was nochange in final alignment whencompared to the immediatepostoperative radiographs. Fractureunion occurred in all thirty patients atan average of 23.5 weeks (range, 13 -57 weeks) from the date ofintramedullary nailing. In the threepatients with associated bone lossrequiring a staged autograft procedure,the average time to healing wassignificantly longer at 44.3 weeks(range, 33 - 57 weeks) (p = .034).

Outcomes EvaluationThe average scores in the eight

categories of the SF-36 were: PF, 65.0;RP, 61.8; BP, 66.2; GH, 70.4; VT, 57.9;SF, 81.3; RE, 90.9; MH, 76.4. Thesevalues were compared to publishednormative values for the generalpopulation (Table 1). A significantdifference was found in three of theeight categories which includedphysical functioning, role limitationsphysical, and bodily pain.

The distribution of values in eachof the ten categories of the MFA istabulated in Table 2 with the normativevalues from uninjured patients. Theaverage MFA for our group of patientswas 23.8 (standard deviation, 14.67)(range, 2 - 44). The total function MFAscore for patients with isolated knee, legand ankle injuries after a year of follow-up is 22.9 (range 2 - 59). Forcomparison, the total function MFA

score for uninjured patients is 9.3(range, 0 - 59).

DISCUSSIONIntramedullary nailing of open and

closed tibial shaft fractures has beenassociated with high rates ofradiographic and clinical success.Fractures distal to the tibial diaphysiswithin five centimeters of the anklejoint may represent a different injuryand have therefore been excluded fromreports on tibial shaft fractures.Potential difficulties associated withfractures in this location include woundproblems associated with limited softtissue coverage, the associatedamplification of the bending momentof the short distal segment of the tibiaabove the ankle joint, and thevoluminous anatomy of the tibialmethaphysis in the plafond. Becauseof the large diameter of the distal tibiarelative to the intramedullary nail theinterface between the cortex of the tibiaand the nail cannot be used to assist infracture reduction in this location.

In our series of patients, thearticular extension was addressed priorto intramedullary nailing of the tibia.This was performed to preventadditional displacement and to assist inreduction of the distal fragment. Lossof reduction of the articular segmentwas not seen with nail insertions.Strategic placement of periarticular lagscrews may help prevent this potentialcomplication. Articular fractures

Study Population Normative ValuesCategory

Avg SD Range Avg SD

p-value

Mobility 37.9 27.1 0-70 11.9 12.7 < 0.001

Housework 34.3 28.2 0-77.8 7.8 15.4 < 0.001

Self-Care 14.8 20.8 0-66.7 1.7 4.4 < 0.001

Sleep & Rest 13.9 23.4 0-66.7 15.5 21.8 0.81

Leisure &Recreation 58.3 28.9 25-100 10.0 21.9 < 0.001

Family Relationships 6.7 17.2 0-60 7.9 16.6 0.81

Cognition & Thinking 10.4 29.1 0-100 6.1 17.3 0.44

Emotional Adjustments 31.0 18.6 5.6-61.1 15.6 12.8 < 0.001

Employment 16.7 34.3 0-100 5.3 16.7 0.047

Table 2: Comparison of Study Population and MFA* Normative Values.

Figure 1: This 58 year old female with ahistory of diabetes sustained this distal tibialfracture with extension into the ankle joint.She was treated with limited open reductionof the articular surface and intramedullarynailing of the tibia.

(1a)

(1b)

(1c)

(1d)

(1e)

-

18 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

Study performed at HarborviewMedical Center, Seattle, Washington,USA

patients had loss of alignment or length.All intraarticular fractures healedwithout displacement. The need forbone graft was seen only in thosefractures with severe bonycomminution in conjunction with softtissue defects.

RECOMMENDED READING

Konrath, G. Moed, B. R. Watson, J. T.Kaneshiro, S. Karges, D. E., and Cramer,K. E.: Intramedullary nailing ofunstable diaphyseal fractures of thetibia with distal intraarticularinvolvement. J Orthop Trauma, 11: 200-205, 1997.

Krettek, C. Stephan, C. Schandelmaier,P. Richter, M. Pape, H. C., and Miclau,T.: The use of Poller screws as blockingscrews in stabilising tibial fracturestreated with small diameterintramedullary nails. J Bone Joint Surg[Br], 81: 963-968, 1999.

Mosheiff, R. Safran, O. Segal, D., andLiebergall, M.: The unreamed tibial nailin the treatment of distal metaphysealfractures. Injury, 30: 83-90, 1999.

Puno, R. M. Vaughan, J. J. Stetten, M.L., and Johnson, J. R.: Long-term effectsof tibial angular malunion on the kneeand ankle joints. J Orthop Trauma, 5:247-254, 1991.

Robinson, C. M. McLauchlan, G. J.McLean, I. P., and Court-Brown, C. M.:Distal metaphyseal fractures of the tibiawith minimal involvement of the ankle.Classification and treatment by lockedintramedullary nailing. J Bone JointSurg [Br], 77: 781-787, 1995.

Ting, A. J. Tarr, R. R. Sarmiento, A.Wagner, K., and Resnick, C.: The roleof subtalar motion and ankle contactpressure changes from angulardeformities of the tibia. Foot Ankle, 7:290-299, 1987.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 19

The isolated coronal fracture ofthe femoral condyle wasoriginally described by Hoffa in1904. This fracture involves the lateralfemoral condyle more commonly, butfractures of the medial condyle havebeen described as well. Nonoperativetreatment has been associated withdisplacement and poor functionalresults. Operative treatment of thesefractures has therefore beenrecommended. These fracturesrepresent a diagnostic dilemma, arefrequently missed, and are associatedwith further displacement ifunrecognized. Computed tomographyhas been recommended as an adjunctin the diagnosis of condylar

involvement in intraarticular distalfemoral fractures.

For combined supracondylar andintercondylar femoral fractures,operative treatment is recommended toprovide stable restoration of thearticular surface and facilitate earlyrange of motion. The associationbetween intercondylar distal femoralfractures and coronal split fractures hasreceived little mention despitenumerous publications on distalfemoral fractures. The purposes of thisstudy are to identify the associationbetween supracondylar intercondylardistal femoral fractures and coronalsplit fractures, and to describe theradiographic evaluation of theseinjuries.

MATERIALS AND METHODSOver a 60 months period from May,

1994 to April, 1999, all patientssustaining an intraarticular fracture ofthe distal femur were collected from aprospectively designed orthopaedicdatabase and reviewed retrospectively.One hundred twelve patients with 117intraarticular distal femoral fractureswere identified and included in theinitial review. Patients withunicondylar (OTA type 33B) injuries (n= 26) were excluded. The remaining86 patients with 91 supracondylarintercondylar distal femoral fracturessurvived their initial resuscitation andwere treated operatively at HarborviewMedical Center, a level one traumacenter in Seattle, Washington.

All Supracondylar IntercondylarFractures

There were 60 male and 26 femalepatients ranging in age from 15 to 88years (average 44.7 years). These 91fractures were classified according toAO and OTA guidelines and included33C1 (n = 8), 33C2 (n = 29), and 33C3(n = 54) injuries. Five patients hadbilateral intraarticular distal femoralfractures. All injuries with a sagittalintercondylar split associated with acoronal fragment of either condyle wereclassified as 33C3. Forty-eight fractureswere open (53%) and included 13 TypeII, 32 Type IIIA, 1 Type IIIB, and 2 TypeIIIC injuries.

Fractures with Associated CoronalSplit Fragments (Hoffa Fractures)

Thirty-seven distal femoralfractures in thirty-six patients had anassociated Hoffa fracture. There weretwenty-seven male and nine femalepatients ranging in age from fifteen toeighty-eight years (average 38.0 years).Twenty-eight of thirty-seven distalfemoral fractures with an associatedHoffa fracture (76%) were open andclassified as Type II (n = 7), Type IIIA(n = 18), Type IIIB (n = 1), and TypeIIIC (n = 2).

The Association Between Supracondylar Intercondylar DistalFemoral Fractures and Hoffa Fractures

SEAN E. NORK, M.D., KAMRAN AFLATOON, D.O., DANIEL N. SEGINA, M.D.,STEPHEN K. BENIRSCHKE, M.D., M.L. CHIP ROUTT, JR., M.D, AND M. BRADFORD HENLEY, M.D., M.B.A.

(1a) (1b)

(1c) (1d)

Figure 1: Injury radiographs and CT scans of a patient with a supracondylar intercondylar distalfemoral fracture with an associated Hoffa fracture. The coronal fracture line is visible on the lateralradiograph. The axial and sagittal reformations further define the injury.

-

20 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

RESULTSHoffa fractures were diagnosed in

thirty-seven of ninety-one (41%)supracondylar intercondylar distalfemoral fractures. One patient hadbilateral intraarticular distal femoralfractures with medial and lateralcoronal split fragments in each knee(four independent condylarfragments). Nine patients hadbicondylar coronal split fractures(medial and lateral) in the sameextremity. Twenty-seven patients hadunicondylar coronal split fractures with85% (n = 23) located laterally and 15%(n = 4) located medially. Thiscombined for a total of forty-sevencoronal split fragments in thirty-sevenknees.

Overall, 53% of distal femoralfractures (AO/OTA type 33C1, 33C2,and 33C3 fractures) were open and67% of AO/OTA Type 33C3 fractureswere open. Open fractures occurred in90% (nine of ten) of extremities withmedial and lateral (bicondylar) Hoffafragments. In fractures with at least oneHoffa fragment, 76% (28 of 37) wereopen compared to 37% (20 of 54) ofintraarticular distal femoral fractureswithout a coronal split fragment (p =.00022).

The average Injury Severity Score(ISS) in these eighty-six patients was18.2 (range, 9-50). The average ISS inpatients with a Hoffa fracture was 20.6(range, 9-50), compared to 16.1 (range,9-50) in patients without a Hoffafracture (p = 0.028). Similarly, inpatients with bicondylar Hoffafractures the ISS with significantly

higher (24.3) than in the remainingpatients (17.1) (p = .019).

A dedicated CT scan of the distalfemur was obtained in twenty-seven ofthe ninety-one knees. In patients witha Hoffa fragment, preoperative CTscans were obtained in thirteen patientsand identified seventeen of these Hoffafractures. Of the forty-seven Hoffafragments, biplanar distal femur plainradiographs were diagnostic in onlythirty-four (72%). Eight additionalHoffa fractures were identified with theaid of the CT scan (Figure 1). In sixpatients, the diagnosis of a Hoffafracture was discoveredintraoperatively. In two of thesepatients, the coronal split fracture wasappreciated during insertion of theangled blade plate seating chisel as thefracture displaced in presumed 33C2type fractures (Figure 2). In bothpatients, the Hoffa fractures was thenreduced and stabilized. The surgicalimplant was changed to a lateralcondylar buttress plate.

Of the forty-seven coronal splitfractures, twenty six were displacedwhile twenty-one were non-displaced.According to the classification systemof Letteneur et al, there were eight TypeI fractures and thirty-nine Type IIIfractures 13. Five Hoffa were segmentalinjuries with multiple condylarfragments.

DISCUSSIONThe presence of a Hoffa fragment

in association with intraarticular distalfemoral fractures has received littleattention, despite numerous

publications on distal femoral fractures.Temporary fixation of the Hoffafragment followed by rigid fixation theof the distal femoral fracture with anangled blade plate has beenrecommended in the past. However,based upon the experience in our studypopulation, fixation of the Hoffafragment prior to stabilization of thesupracondylar and intercondylarfracture fragments is recommended(Figure 3).

The complexity of the fractures inthis series reflects the patientpopulation at this primary and tertiaryreferral Level one trauma center. Ofninety-one supracondylar-intercondylar distal femoral fractures,only eight were true “T” intercondylarfractures without articular ormetaphyseal-diaphyseal comminution(Type 33C1 fractures). Overall, onlyseventeen of fifty-four (31%) 33C3distal femoral fractures did not have acoronal split fracture. The presence ofa coronal split fracture in over 40% ofall supracondylar-intercondylar distalfemoral fractures is concerning, asimplant choice may be altered based onthis finding.

The lateral condyle is involved morefrequently than the medial condyle inboth unicondylar fractures, as well asisolated Hoffa fractures. In all thirteencases of two combined series, theisolated Hoffa fracture was of the lateralcondyle. In our series, 85% (23/27) ofpatients with unicondylar coronal splitfractures had lateral condyle injuries.However, 36% (14/47) of coronal splitfractures were of the medial condyle inall patients with at least one Hoffafragment.

The largest series of isolated coronalunicondylar fractures (OTA type 33B3)was reported by Letenneur et al andconsists of twenty cases. Surgicaltreatment of displaced fractures wasrecommended and produced betterresults than nonoperative care. The fateof untreated or unrecognized coronalsplit fragments has been described intwo series. Lewis et al reported onsubsequent malreduction in twopatients with unrecognized, initiallynondisplaced coronal split fractures.Similarly, Butler et al reported on twopatients with unrecognized Hoffafragments which ultimately required asecond surgical procedure forreduction and fixation. In our series,all recognized Hoffa fragments were

Figure 2: Intraoperative clinical image of the coronal fracture line of the lateral femoral condyle.

-

2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT 21

stabilized at the time of distal femoralfixation.

Recognition of these injuries,especially nondisplaced fractures, isoften difficult with AP and lateral plainradiographs. The potentialcomplication of a missed Hoffa fractureincludes displacement intraoperativelyor postoperativley. More importantly,the implant choice based on thepreoperative plan can be appropriatelyadjusted in the presence of a Hoffafragment. Orthogonal plainradiographs, even during retrospectivereview, demonstrated the fracture inonly thirty-four of the forty-sevencoronal split fragments, emphasizingthat non-displaced Hoffa fractures maybe overlooked easily. CT scans, whichwere obtained in only 27 of 91 cases,demonstrated the fragment in sevenadditional cases. Six fragments (13%)were identified at the time of surgicalstabilization. None of these six patientshad a preoperative CT scan. Given theincidence of coronal plane fractures inhigh energy distal femoral fractures,combined with the frequency ofnondisplaced fragments, preoperativeCT scans may be helpful in identifyingthese injuries. This is especially true infractures where the planned approachdoes not include direct visualization ofthe articular surface.

In this series of predominately blunttrauma patients (96.5%), the majorityof these injuries were open (53%). The

incidence of associated open traumaticwounds in patients with distal femoralfractures ranged from 17 - 31%.However, in reports of comminuteddistal femoral fractures, open woundsoccur in 40 - 56% of patients. Our openfracture incidence of 67% of AO type33C3 fractures and 53% of all AO Type33C fractures is reflective of the highenergy patient population reviewed.Consistent with the incidence ofcomminution in combined distal femurand coronal split fractures, theincidence of associated open woundsincreased to 70% (19/27) in patientswith unicondylar involvement and 90%(9/10) of patients with combinedmedial and lateral coronal splitfractures. The presence of at least oneHoffa fragment with an intercondylardistal femoral fracture was associatedwith a higher rate of associated openwounds. Similarly, an open fracturewas associated with an increased riskof a coronal split fragment.

CONCLUSIONSThe 41% incidence of Hoffa

fractures in association withsupracondylar-intercondylar distalfemoral fractures is higher thanexpected. Involvement of both themedial and lateral condyles occurred in27% of these injuries. In unicondylarinjuries, the lateral condyle was affectedmuch more frequently (85%) than themedial condyle. Open associated

Figure 3: Postoperative radiographs after fixation of the Hoffa fracture and the distal femoralsupracondylar intercondylar fractures.

(3a) (3b)

wounds occurred in 76% of thesefractures. In our patients, an openinjury was associated with an increasedrisk of a Hoffa fracture. The diagnosisis often difficult and CT scanning maybe required in supracondylar fractureswith intercondylar extension.

RECOMMENDED READING

Bolhofner, B. R. Carmen, B., andClifford, P.: The results of openreduction and Internal fixation of distalfemur fractures using a biologic(indirect) reduction technique. JOrthop Trauma, 10: 372-377, 1996.

Johnson, E. E.: Combined direct andindirect reduction of comminutedfour-part intraarticular T-typefractures of the distal femur. ClinOrthop, 231: 154-162, 1988.

Letenneur, J. Labour, P. E. Rogez, J. M.Lignon, J., and Bainvel, J. V.: [Hoffa’sfractures. Report of 20 cases (author’stransl)]. Ann Chir, 32: 213-219, 1978.

Lewis, S. L. Pozo, J. L., and Muirhead-Allwood, W. F.: Coronal fractures of thelateral femoral condyle. J Bone JointSurg [Br], 71: 118-120, 1989.

Ostermann, P. A. Neumann, K.Ekkernkamp, A., and Muhr, G.: Longterm results of unicondylar fractures ofthe femur. J Orthop Trauma, 8: 142-146, 1994.

Sanders, R. Swiontkowski, M. Rosen,H., and Helfet, D.: Double-plating ofcomminuted, unstable fractures of thedistal part of the femur. J Bone JointSurg [Am], 73: 341-346, 1991.

-

22 2001 ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH REPORT

Operative fixation techniques forunstable sacrum fracturesinclude open or percutaneousiliosacral screw osteosynthesis, tensionband transiliac plate osteosynthesis,transiliac bars and local plateosteosynthesis. Each allows earlypostoperative patient mobilization withonly partial weight-bearing. However,patient non-compliance, accidental fullweight-bearing, poor bone quality anddelayed union for various reasons resultin loss of reduction in up to 26% ofpatients.

Some sacral fracture fixationtechniques were evaluated withbiomechanical testing, and proved to besimilar in immediate stability.Nevertheless, these biomechanical testsinvolved only load to failure underconstraint conditions or stability testingwith only a few loading cyclessimulating the immediatepostoperative time period. Themajority of these tests were performedin a double-leg stance model, whichfails to account for the larger loadsacross the fracture during single limbstance. Cyclic loading simulating pelvicfixation loading during thepostoperative period of bony healingunder full weight-bearing conditionshas not been performed.

Triangular osteosynthesis forunstable sacrum fractures has beenrecently described. This fixationtechnique combines lumbopelvic

distraction osteosynthesis with atransverse fixation (iliosacral screwosteosynthesis or tension bandtransiliac plate osteosynthesis)providing clinically sufficientmultiplanar stability. This posteriorpelvic stability uniquely allows earlypostoperative full weight-bearing.

The purpose of our study was (1)to create a biomechanical set-upallowing for cyclic loading of pelvicspecimens in a single-leg stance model,and (2) to compare the stabilities oftriangular lumbopelvic and iliosacralscrew osteosyntheses for unstabletransforaminal sacral fractures, both atinitial loading and through 10,000cycles.

MATERIALS AND METHODSTwelve embalmed human cadaveric