1992 Brood Adoption BES

-

Upload

irina-cristea -

Category

Documents

-

view

228 -

download

0

Transcript of 1992 Brood Adoption BES

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

1/7

Behav E col Sociobiol (1992) 31:263-269 Behavioral Ecologyand Sociobiology~, Springer-Verlag1992

Intraspecific brood adoption in convict cichlids: a mutual benefitBrian D. Wisenden and Miles H.A. KeenleysideDepartment of Zoology,Universityof Western Ontario, London O ntario, Canada, N6A 5B7Received Decembe r5, 1991/Accepted May 10, 1992

Summary. Convict cichl ids (Cichlasoma nigrofasciatum)are biparental , substrate brooding cichl id fish whichhave extended care of their eggs, larvae (wrigglers) andfree-swimming young (fry). Field observat ions indicatethat intraspecific broo d adop tion o f fry occurs frequent-ly under natural condit ions. Of 232 broods 29% con-tained foreign fry and of 232 broo ds 15% were identifiedas fry donors. Foreign fry were usual ly of similar sizeto or smaller than the host brood fry. Experimental frytransfers showed tha t paren ts accept foreign fry smallerthan their own b ut imm ediately reject or eat foreignfry larger than their own. A predat ion experimentshowed tha t within a mixed broo d, smaller fry are eatenmore often than larger fry. Thus, accepting foreign frymay benefi t parents through the di lut ion effect andthrough a different ial predat ion effect . In comparisonwith intact famil ies, brood s from which the male parentwas re mov ed were less l ikely to re ach indepen dence, hadfewer fry surviving to independence, and had a greaterprobabil i ty o f having some fry t ransferred to neighbou r-ing broods. We propose that intraspecific brood adop-tion in con vict cichlids is mutu ally beneficial to the adu ltdonors and recipients.

IntroductionA well-known feature of fish in the family Cichl idaeis the parental care of their eggs and free-swimmingyou ng (fry) for several weeks (Fryer and Iles 1972; Keen-leyside 1991). Such high levels of parental care are alarge parental investment and are thought to be neces-sary to compensate for high potent ial brood predat ion(Barlow 1974).In laboratory experiments, parental cichl ids can beinduced to adopt and care for eggs and f ry f rom otherconspecific and heterospecific brood s (Noble an d Curt is1939; Greenberg 1963; Burchard 1965; Myrberg 1964;Correspondence to. B.D. Wisenden

Noakes and Barlow 1973; Baylis 1974; Mrowka 1987a,c). These findings are supported by field observat ions(McKaye and Hallacher 1973; Lewis 1980; McKaye1977, 1985; McKaye and McKaye 1977; Ward and Wy-man 1975, 1977; Ribbink 1977; Ribbink et al . 1980;Yanagisawa 1985).Laboratory experiments (Greenberg 1963; Myrberg1964; Noakes and Barlow 1973; Baylis 1974; Mrowka1987b) and field observat ions (McKaye and McKaye1977; Ribbink 1977; Carlisle 1985; Yanagisawa 1985)have shown that am ong cichl id fishes an im por tant cri te-rion fo r acceptance of foreign fry (inter- or intraspecific)by foster parents is the size of those fry relative to theirown. The general conclusion from these studies is thatcichl id parents readi ly accept foreign fry of the samesize or smaller than their brood, but reject larger fry.The adaptive significance of this phenomenon has re-ceived little attention .Brood adoption in cichl ids has at t racted at tent ionbecause parental investment in non-related young ap-pears to be maladaptive. However, i f predat ion on hostfry is reduced by di lut ing the brood with foreign fry(the "di lut ion effect"), then natural select ion wil l pro-mote brood adopt ion (M cKaye and M cKaye 1977).If the di lut ion effect benefi ts host paren ts that adop tforeign fry, can this benefi t be enhanced if the hostsselectively adop t only certain fry? S ome au thors observ-ing interspecific brood adoption have suggested that agrea te r vulnerabi li ty of adop ted yo ung to preda tors m ayincrease the benefi t to host p arents (M cKaye and Oliver1980; Goff 1984). One hypothesis tested in this paperis that host parents can increase the potent ial benefi tof adoption by accepting fry smaller than their own.If smaller fry are more easi ly taken by predators thanlarger fry, then when a predator at tacks the brood, thesmaller, foreign fry wil l suffer a disproport ionateamount of mortal i ty. Thus, survival of the host frywould be increased above what would be predicted bythe dilution effect alone.The convict cichlid (Cichlasoma nigrofasciatum) is aCentral Am erican, substrate broo ding species which has

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

2/7

26 4bipare ntal care o f its eggs, wrigglers (larvae) and fry.This paper docum ents f ield observations o f intraspecif icfry adoption by convict cichlids in Costa Rican streams.Preliminary work indicated that adopted fry were usual-ly smaller than host fry. Experimental fry transfers be-tween broods were conducted in the f ield to investigatethe possibil i ty that parental discr imination explains thesize difference between foreign .fry and host fry. A labo-ratory experiment was designed to test whether or notfry of different sizes differ in their vulnerability to broodpredators. Parental male convict cichlids occasionallydesert the brood and female before fry independence(Keenleyside et al. 1990). D eserte d females ma y not beas effective at defending a brood from predators as twoparents. We hypothesized that when faced with reducedprospects of fry survival , deserted females should showa higher incidence of fry transfer to neighbouring broodsthan biparental families do. A male removal experimentwas conducted to determine the contr ibution of maleparental care to fry survival and to assess the effect ofmale desert ion on fry adoption.

Materials and methodsObserva t ions of convic t c ich l id reproduct ive eco logy were madewithin the species ' natural range (Bussing 1987) in Guanacasteprovince, northwest Costa Rica, during two breeding seasons, Jan-uary to June 1990 and December 1990 to June 1991. The studysites were located in small streams at Lomas Barbudal BiologicalReserve, 1030'N, 852YW. Four study si tes were used, represent-ing two habitat types. Two sites were in the Rio Cabuyo and twowere in the Quebrada Amores , a t r ibu ta ry of the Rio Cabuyo.In each stream, one si te was a relat ively deep, wide pool ("poolsi te") and the other was a series of small , shallow, interconnectedpools (" stream site") .Convict cichlid breeding activity was monitored at each si te.Spawning locations were marked with f lagging tape (1990) orpainted stones (1991). Parents were marke d as follows when theirbrood became f ree-swimming. Paren ts and young were sur roundedwith a f ine-mesh black seine. The male was captured first becausehe was the most l ikely to f lee. Next, al l fry were captured usinghand nets. The female parent always rema ined close to the frywhile they were being captured, and any fry that strayed, quicklyreturned to her. The female was then captured. Each parent wasanaesthetized with MS222 (tr icaine methanesulfonate), weighed,measured, and given a unique identifying mark by excising twodorsal spines. Detailed sketches were made of the body markingsof each parent for later identif ication. Fifteen fry were randomlychosen, anaesthetized with MS222 and their standard length (SL)measure d to th e nearest 0.5 ram. The to tal num ber of fry in thebrood was recorded. When all f ish had recovered from the anaes-thetic, the parents were gently returned to their capture si te, whichwas st i l l surroun ded by the seine to exclude potential fry predators.Upon release, the male often fled and hid. However, the female.soon began to search the area for her fry. The fry were then reintro-duced using a clear plastic tube. When the tube was l if ted thefemale approached the f ry and resumed normal brood defencebehaviour . The male usua l ly jo ined the female in brood defencesoon after the fry and the female were reunited. Controls test ingfor mortali ty caused by handling showed a loss of 0.78 fry persample.Individual families were identif ied by their location in thes t ream, the s tage of f ry deve lopment , and the body markings ofthe parents. At regular intervals (usually 7 days) each brood wasrecaptured as before. The parents were left in the water with somefry (< 10) to keep the adults from wandering in search of missing

fry. A visual count of the remaining fry was made using face maskand snorkel. The captured fry were counted and 15 were randomlychosen, anaesthetized and measured. When clearly different sizegroups appeared in a brood , the mean length and numb er of eachsize group was recorded. T he fry were then returned to the adultsas described above.When two or more size groups were found in a brood, or whenthe number of fry in a brood increased over t ime, that broodwas considered to be a fry receiver or host brood. We knew whichsize group was the host fry and which was foreign because wefo l lowed each brood for the dura t ion of f ry deve lopment . For eachmixed brood, an attempt was made to match the size of the foreignfry to those of a neighbouring brood, which was then labelledas the f ry g iver or donor brood . W hen there were no ne ighbour ingbroods matching the foreign fry size, no brood was ascribed asthe donor. On three occasions the size of foreign fry in a mixedbrood m atched more than one ne ighbour ing brood . In these cases ,other factors such as proximity and fry number were used to labelone as the donor brood .Fry transfer experiment. Altogether 25 experimental fry transferswere made to determine if the size difference between host andforeign fry was maintained by discrimination on the part of hostparents. Transfers were made by capturing fry from one broodand placing them directly into another, using a clear plastic tube.The mean SL of added fry was either larger (mean size difference_+SE=2.13_+0.28mm , n=9 ) or smal le r (mean size d i f ference=1.92_+0.14 mm, n=1 6) than the mean f ry SL of the rece iv ingbrood. These size differences (2.13 and 1.92) were not significantlyd i f feren t f rom each o ther ( t=0 .73 , P

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

3/7

Table l. Occurrence of fry adoption by convict cichlids at foursites in Lomas Barbudal Biological Reserve during 1990 and 1991Site Broods Adoption Gave Rece iveddetected

n % n % n %Amores Pool 64 25 39 13 20 12 19Amores Stream 44 8 18 1 2 8 18Cabuyo Pool 65 27 42 12 18 18 28Cabuyo Stream 59 37 63 9 15 30 51Total 232 97 42 35 15 68 29Some broods both gave and received fryTable 2. Percentage of broods with access to neighbouring broodsand mean distance to nearest neighbouring broods at each site,for all samples combinedSite With accessibleneighbouringbrood

Distance to nearestneighbouring brood (m) t

n % Y SE nAmores Pool 185 99.5 4.53" 0.24 173Amores Stream 169 71.6 3.64 "b 0.21 112Cabuyo Pool 225 98.7 2.97 b 0.02 217Cabuyo Stream 302 91.1 1.97 c 0.35 262Total 881 91.0 3.08 0.15 764* Differences among sites are significant (F= 14.49, P

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

4/7

2661 4

~ 12EEw 10~" 8~-

o4

1990 o ~o 1991 o

Oooo % / oo e/ ~ ~,~Oo Oo "~:~ ~,o

~ o~)'- ~ oo o

Line o fequality

I I I I I I2 4 6 8 10 12 14

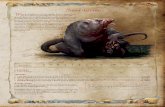

Host Brood Fry SL (rnm)Fig. 2. Mean size (SL in ram) of foreign fry and host fry in mixedbroods (n = 84 events in 68 broods). Male remov al and fry transfermanipulations not included. Line of equality indicates equal sizeof host and foreign fry. Filled circles, 1990; open circles, 1991

E 4

~ , 3

IJJ 2

6 1Z

C. doviiD C. nigrofasciatum

5 6 7 8F r y S ta n d a r d L e n g th (mm)

Fig. 4.Number of Cichlasoma nigrofasciatum fry of each size groupwithin a mixed school that were eaten by single C. dovii (n= 10)(solid bars), or grou ps of 3 juvenile C. nigrofasciatum (n = 10) (openbars) in 15 rain. Bars represent mean + SE

12

E 10E._1tJ)> , 8t.I.i."o~o 6 6 mm = 7 mm = 8 mm ) ( S tu-d e n t - N e w m a n - K e u l s , P < 0 .0 5 ).

80 177 40

6 4

~ 48~(J~~ 32

16

21

13 9

[ ] Population Male Removals

. 21

~ Brood s No, Fry ~ Broodsto Indep at Indep Transferred

30 ~"- -

N~, ~

2o ~-.~~,,~lO E-~Z

Fig. 5. A comp arison of two measures o f reproductive success andrate of fry transfer among broods in the unmanipulated populatio n(open bars) with broods from which the male parent had beenremoved (solid bars). For comparison purposes, percentage ofbroods to independence in the unmanipulated population was cal-culated from broods surviving from 7 mm SL to independence(10 mm fry SL). Numbers above bars represent sample sizes. * indi-cates a significant difference at P< 0.05, *** indicates a significantdifference at P 1 0 m m f r y S L ) i n t h e g en e r a l p o p u l a t i o n

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

5/7

Table 3. The fate of broods from whic h the m ale parent was re-moved half way through the free-swimming ry stage (n = 21)Relative size of fry in Fry Female rem ain ed Broodneighbour ing broods transfe rred with brood failedLarger, similar 5a 1 2and smallerLarger only 3 1 lSimilar size only b 1Smaller only 5No neighbours 2Total 8 5 8" Thre e broods and part of a fourth brood wer e transferred tobroods with larg er fry, one brood and part of a se cond broodwere transferred to broods w ith fry of similar size (host fry weresmaller than adopted fry by 0.60 mm and 0.88 mm SL)b Two neighbouring broods w ere nearby containing fry larger thanthe male removal brood by 0.04 mm and 0.17 mm SL

was 28 .57+2.01 (n=139) , over 1 .5 t imes the meannumber of f ry surv iv ing to independence for male- re-moval broods (17.00_+ 5.19, n= 5). This difference is sig-nifi can t (l-tail ed t = 2.08, P < 0.046) (Fig. 5).Fry f rom 8 of the 21 male- remo val b roods were l a terd i scovered in neighbour ing broods (Table 3 ) . When amale removal resu l ted in f ry t rans fer , f ry were a lwayst rans fer red to neighbour ing broods whose f ry were e i -ther o f s imi lar si ze o f l arger than the t rans fer red f ry(Table 3). This is consis tent with the natural populat ionadopt ion data (Fig . 2 ) .The incidence of f ry t rans fer among male removalbroo ds (8 of 21) was s ignifiant ly greater th an the inci-dence of f ry donat ion detec ted in the unmanipula tedpopula t ion (35 of 232) (Fi sher ' s exact t es t P

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

6/7

268Conditions benefitting fr y recipientMcKaye and Hal lacher (1973) and McKaye andMcKaye (1977) proposed that parents accepting foreignfry benefi t through the "dilution effect". A str ike bya broo d p redato r results in the loss of one or a fewfry, not an ent i re brood. Given tha t brood preda torswill take some f ry, parents can reduce the probabil i tyof their own youn g being taken by diluting their broo dwith foreign fry. Accepting foreign fry should benefi tparents as long as the addit ion of foreign fry does notresult in signif icant increases in bro od defence, increasedpredator at tack rate (Pitcher 1986) or increased competi-t ion for food among fry (Perrone 1978b) .Foreign fry and host f ry may not be equally vulnera-ble to predators. Accepting foreign fry may be advanta-geous to the host if adop ted fry are suff iciently differentfrom host f ry that they are singled out more easi ly bya predator (Ribbink etal . 1980) . The presence ofadopted fry benefi t host f ry in interspecif ic cichlid-cat-f ish broods where adopted cichlid f ry remain on theper iphery o f the broo d and rece ive a dispropor t iona tenum ber o f pred ator at tacks, spar ing the host catf ish fry(McKaye and Oliver 1980; McKaye 1985) . Similar ly,Go ff (1984) obs erved eggs and larvae o f longno se gar(Lepisosteus osseus) on the per iphery o f smal lmouth bass(Micropterus dolomieui) nests and hypothesized that garfry receive man y o f the at tacks by bro od p redators. Per-rone (1978b) tested vulnerabil i t ies of different sizes ofCichlasoma maculicauda fry to a Gobiomorus sp. preda-tor and fo und the rate of capture to be highest in smallfry.In our study, smaller convict cichlid f ry were morevulnerable than larger f ry to two important brood preda-tors (Fig. 4) . Host parents can benefi t in two ways whenthey accept foreign fry smaller than their own. Pred ationon their young is reduced by diluting their brood withforeign fry ( the "dilution effect") and i t is fur ther re-duced by adopting small foreign fry which serve as pre-dation targets ( the "differential predation effect") . I tfollows that for parents to accept f ry larger than theirown would put their f ry at a disadvantage. Therefore,i t could be predicted that parents accepting foreign fryshould be vigilant and not accept f ry larger than theirown, but readily accept f ry of similar size or smallerthan their f ry. The greater the size advantage of thehost f ry over the foreign fry becomes, the greater thedifferential predation effect .Conditions bene fitting fr y donorParental care is an energetically costly endeavour whichdepletes body energy reserves, delays remating oppor-tunit ies and increases predation r isk to the car ing parent(Gross and Sargent 1985) . I t is an obvious benefi t toreduce these costs, provided that the parent(s) can beconfident that their offspr ing have a reasonable chanceof survival with foster parents. However , in a mixedbrood, smaller foreign fry suffer f rom proportionatelyhigher ri sk of preda t ion and becom e independent a t a

smaller size than host f ry. Under normal condit ions, pa-rental con vict cichlids should be better off raising theirown y oung, I f prospects of successfully rear ing fry toindependence are reduced, as was shown for broodswithout male parents (Fig. 5) , then fry transfer to fosterparents may become advantageous .Ma te deser t ion by male convict cichlids has been doc-umented in experimental ponds and in the f ield (Keen-leyside et al. 1990; Keenley side and M acke reth 1992)and o ccurred in 7.8% of al l broo ds during this study(unpubl i shed da ta) . W hen one parent o f a b iparentalspecies leaves the family, the burden of parental careis increased for the remaining parent (Mrowka 1982;Keenleyside et al. 1990). Thus, when a male deserts, theprobabil i ty of rear ing fry to independence is reduced(Keenleyside 1978; Keenleyside and Bietz 1981). Facedwith possible brood fai lure, a deser ted female parentshould be inclined to compromise and accept the disad-vantaged status her f ry may have in a foster brood.The male removal experiment simulated male deser-t ion and resulted in the transfer o f f ry to neighbo uringbroo ds (Table 3; Fig. 5). Aspects of our results are com-parable to those o f Yanagisaw a (1985). He remo ved ei-ther the male or female parent f rom the Lake Tanganyi-kan cichlid Perissodus microlepis, a biparental mouth-brooder , where both sexes defend the fry. The removalof one paren t resulted in increased brood pred ator at-tack rates and higher predation losses. He found evi-dence of "fa rming out" by s ingle males and femalesin 14 (54%) of 26 test broods. Single parents of 7 (27%)of his 26 test bro ods remained with their bro ods forat least 7 days af ter mate removal. In our study 8 (57%)of 14 male removal broods where ne ighbour ing broodsof same size or larger f ry were present transferred fry,and 5 females (24%) o f 21 broods rem ained with theirbrood (Table 3) .Experimental f ry transfers were only successful in ourstudy when fry of the receiving bro od were larger thanthe foreign f ly (Fig. 3) . Some researchers have succeededin transferring similar-sized fry between conspecific cich-l id broods in the f ie ld (McKaye and McKaye 1977;McKaye and Hallacher 1973; Carlisle 1985), whileothers observed that al l a t tempts to experimentally in-troduce foreign fry into broods were rejected by the par-ents when the foreign fry were similar in size (Ribbinket al. 1980; Yanagisawa 1985), or were smaller and largerthan host f ry (Perrone 1978 a).

I t is unclear how much of the size distr ibution infry seen in Fig. 2 is also attributable to discriminationon the par t o f the f ry donor . M ale- removal b roodswhose only neighbouring broods contained fry smallerthan their own fai led 5 out of 5 t imes (Table 3). Perhapsfry transfers were at tempted by these lone females andrejected by the receiving parents. When a choice wasavailable, success was mixed, perhaps as a result of at-tempting to transfer large fry to a foster bro od of smallerfly.

-

8/3/2019 1992 Brood Adoption BES

7/7

269Conclusions

I n t r a sp e c i f ic b r o o d a d o p t i o n i n v o l v e d at l e a st 97 b r o o d s( 68 b r o o d s w e r e f r y r e c ei v e r s, 3 5 w e r e f r y d o n o r s ) o ft h e 23 2 b r o o d s m o n i t o r e d i n t h is s tu d y . T h e a r g u m e n tm o s t f r e q u e n tl y p u t f o r w a r d t o e x p la i n h o w n a t u r a l s e-l e c t i o n c o u l d f a v o u r f r y a d o p t i o n i s t h e d i l u t i o n e f f e c th y p o t h e s i s . T h e d i l u t i o n e f f e c t c o u l d b e p o t e n t i a l l yg r e a t l y e n h a n c e d b y p a r e n t s a c c e p t i n g o n l y f r y o f s im i l a ro r s m a l l e r s i z e w h i l e r e j e c t i n g l a r g e r f r y . S m a l l f r y a r em o r e v u l n e r a b l e to b r o o d p r e d a t o r s ; t h u s w h e n b r o o dp r e d a t o r s a t t a c k , s m a l l f o r e i g n f ry h a v e a g r e a t e r p r o b a -b i l i t y o f b e i n g t a k e n , w h i c h s e r v es t o f u r t h e r d e f l e c tb r o o d p r e d a t i o n a w a y f r o m h o s t f ry (t h e d i f f e r e n t i a l p r e -d a t i o n e f f e c t ) .

F u r t h e r e x p e r i m e n t a t i o n s h o w e d t h a t i n t r as p e c i fi c fr ya d o p t i o n i n c o n v i c t c i c h li d s is b e n e fi c i a l b o t h t o t h e f r yd o n o r a n d t h e f r y re c i p i e n t. S u r v i v a l o f f o r e i g n f ry isl o w e r t h a n t h a t o f f r y b e i n g c a r e d f o r b y t h e i r o w n p a r -e n t s ( F ig . 5 ), a n d o f t e n t h e i r p e r i o d o f p a r e n t a l p r o t e c -t i o n e n d s a t a y o u n g e r a g e o f d e v e l o p m e n t . T h e r e f o r e ,p a r e n t s s h o u l d g e n e r a l l y b e e x p e c t e d t o c a r e f o r t h e iro w n y o u n g w h e n p o s s i b l e . W h e n p r o s p e c t s f o r s u c c e s s -f u l ly r e a r i n g t h e ir y o u n g t o i n d e p e n d e n c e a r e l o w , su c ha s w h e n t h e m a l e p a r e n t d e s e r t s , th e n f r y t r a n s f e r t oa n o t h e r b r o o d b e c o m e s a d v a n t a g e o u s .Acknowledgements. We gratefully acknowledge valuable field assis-tance by P. Wisenden, J. Christie, G. de Gannes, O. Steele, R.Jos6 Jimdnez; and logistic suppo rt in the field by G. a nd J. Frankie,the Stewart family, and the Servicio de Parques Nacionales deCosta Rica. The quali ty of the manuscript was greatly improvedby helpful comments from T. Laverty, J. Petrik, D. Urban, G.de Gannes and two anonymous referees. This research was sup-ported by grants to M .H.A. Keenleyside from the N atural Sciencesand Engineering Research Council of Canada.ReferencesBarlow GW (1974) Contrasts in social behavior between CentralAmerican cichlid fishes and coral-reef surgeon fishes. Am Zool14:9-34Baylis JR (1974) The be havior and ecology of Herotilapia multispin-osa (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Z Tierpsy chol 34:115 ~46Burchard JE Jr (1965) F amily structure in the dw arf cichlid Apisto-gramma tr(fasciatum Eigenmann and Kennedy. Z Tierpsychol22:150-162Bussing WA (1987) Peces de las aguas continentales de Costa Rica.Editorial de la Universidad de Co sta Rica, San Jos6Carlisle TR (1985) Parental response to brood size in a cichlidfish. Anim B ehav 33:234-238Coyne JA, Sohn JJ (1978) Interspecific brood care in fishes: recip-rocal altruism or mistaken identi ty? Am N at 112:447 450Fryer G, lies TD (1972) The cichlid fishes of the great lakes ofAfrica. TFH Publications, New JerseyGoff GP (1984) Brood care of longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus)by smal lmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieui). Copeia 1984:149152Greenberg B (1963) Parental behavior and imprinting in cichlidfishes. Beh avi our 21 : 127 144Gross M R, Sargent RC (1985) The evolution of male and femalepare ntal car e in fishes. Am Zoo l 25 : 807-822

Keenleyside MHA (1978) Parenta l care beha vior in fishes andbirds. In: Reese ES, Lighter FJ (eds) Contrasts in Behavior.John W iley and Sons, New York, pp 1-19Keenleyside MH A (1991) Parental care. In: Keenleyside MH A (ed)Cichlid fishes: Behaviour, ecology and evolution. Cha pman andHall, New York, pp 191 208Keenleyside MHA, Bietz BF (1981) The reproductive behaviourof Aequidens vittatus (Pisces, Cichlidae) in Surinam, SouthAmerica. Env Biol Fish 6:87- 94Keenleyside MHA, Mackereth RW (1992) Effects of loss of maleparents on b rood survival in a biparental cichlid fish. Env BiolFish 34:207 212Keenleyside MH A, Bailey RC, Young VH (1990) Variation in themating system and associated parental behaviour of captiveand free-living Cichlasma n~ro~sciatum (Pisces, Cichlidae).Behaviour 112:202-221Lewis DSC (1980) Mixed species broods in Lake Malawi cichlids:an alternative to the cuckoo theory. Copeia 1980:874-875McKaye KR (1977) Defence of a predator 's young by a herbivo-rous fish: an unusual strategy. Am Nat 1 ll :301 315McKaye KR (1985) Cichlid-catfish mutualist ic defence of youngin Lake M alawi, Africa. Oecologia 66:358-363McKaye KR, Hallacher L (1973) The midas cichlid of Nicaragua.Pac Discov ery 25 : 1 8McKaye KR, McKaye NM (1977) Communal care and kidnappingof young by paren tal cichlids. Evolution 31:674-681McKaye KR, Oliver MK (1980) Geometry of a selfish school:Defence of cichlid young by bagrid catfish in Lake Malawi,Africa. A nita Behav 28 : 1287-1290Mrowka W (1982) Effect of removal of the mate on the parentalcare behaviour of the biparental cichlid Aequidens paraguayen-sis Anim Behav 30:295 297Mrowka W (1987a) Brood adoption in a mouthbrooding cichlidfish: experiments and a hypothesis. Anita Behav 35:922 923Mrowka W (1987b) Egg stealing in a mouthbrooding cichlid fish.Anim Behav 35:923-924Mrow ka W (1987c) Final cannibalism and reproductive successin the mou thbroo ding cichlid fish Pseudocrenilabrus multicolor.Behav Ecol Sociobiol 21:257 265Myrberg A A Jr (1964) An an alysis of the preferential care of eggsand you ng b y adu lt cichlid fishes. Z Tierps ycho l 21 : 53-98Noakes DLG, Barlow GW (1973) Cross fostering and parent-off-spring responses in Cichlasoma citrinellum (Pisces, Cichlidae).Z Tierpsyc hol 33 : 147-152Noble GK, Curtis B (1939) The social behaviour of the jewel fishHemichromis bimaculatus Gill . Bull Am Mus N at H ist 76:1~46Perrone M Jr (1978 a) The enconom y of broo d defence by parentalcichlid fishes, Cichlasoma maculicaudu. Oikos 31:137-141Perrone M Jr (1978b) Ma te size and breed ing success in a mon oga-mous cichlid fish. Env Biol Fish 3:193-201Pitcher TJ (1986) Functions o f shoaling behavio ur in teleosts. In:Pitcher TJ (ed) The behaviour of teleost fishes. Croom Helm,London, pp 294-337Ribbink AJ (1977) Cuckoo among Lake Malawi cichlid fish, Na-ture 267 : 243 244Ribbink A J, Marsh AC, Marsh B, Sharp BJ (1980) Parental beh av-iour and mixed broods among cichlid fish of Lake Malawi.S Afr Tydskr Dierk 15(1): 1-6Ward JA, Wyman RL (1975) The cichlids of the resplendent isle.Ocean s 8 : 42-47Ward JA, Wym an RE (1977) Ethology and ecology of cichlid fishesof the genus Etroplus in Sri Lanka: preliminary findings. EnvBiol Fish 2:137-145Yanag isawa Y (1985) Parental s trategy of the cichlid fish Perissodusmicrolepis, with particular reference to intraspecific brood'far min g ou t'. Env Biol Fish 12:241 249