195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

Transcript of 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

1/48

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

2/48

A U6U ST II, 12, 13, 14

Inter-TribalCeremonialAt Gallup, LARGEST and most fa-mous of all Indian expositionsthe Gallup, New Mexico Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial will rollback the march of time for four event-packed days. August II. 12, 13 and14.

Among the festival highlights will benightly presentation of Indian dances,rituals, chants and songs; an all-Indianrodeo performed during the afternoonsof the last three Ceremonial days; acolorful street parade of all-Indiandance groups, bands and Indian horse-men and wagons takes place on Friday,Saturday and Sunday mornings; at theexhibit hall on the Ceremonial Groundswill be displayed the country's mostcomplete and varied collection of In-dian handicraft in silver, turquoise,baskets, pottery, rugs, leatherwork,bead work and original paintings plusdemonstrations of sandpainting.All seats are reserved for all perfor-mances. Tickets can be obtained bywriting to the Inter-Tribal Indian Cere-monial Ticket Office, Box 1029, Gal-lup, New Mexico . Tickets arc also onsale during the Ceremonial at theCeremonial Hogan.Gallup accommodations include 10hotels and 36 motels besides roomsmade available in private homes. Dor-mitory facilities are set up in publicbuildings and the city has several trailer

camps and camping space. Picnic andovernight camping spots arc availablein the nearby Cibola National Forest.Again scheduled this year is an openmeeting during the Ceremonial featur-ing the country's leading experts onIndian affairs speaking on topics bear-ing on the Indian.Professional and amateur photog-raphers are reminded that special per-mits to take pictures are necessary.

Above Taos Dancers in traditionalcostumes await their turn to performat Cerem onial. Photograph by Rob-ert Watkins.Below Apaches in gala array. Themen on the right are the famousdevil-dancers.

D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

3/48

D E S E R T C A L E N D A RAugust 2 Annual Fiesta. JemezHieblo, Albuquerque, New Mexico.August 4Annual Fiesta. Santa Do-mingo Pueblo, Albuquerque,NewMexico.August 4-6 Burro Race, AppleValley, California.August 5-7Cowboys' Reunion Ro-deo, LasVegas, NewMexico.August 10 Annual Fiesta, AcomaReservation, Albuquerque, NewMexico.August 11-14 Inter-Tribal IndianCeremonial, Gallup, NewMexico.August 12-13 Northern ArizonaSquare Dance Festival, Flagstaff,New Mexico.August 12-14Payson Rodeo, Pay-son, Arizona.August 12-14 Smoki Indian Cere-monials, Prescott, Arizona.August 13-14Desert Peaks Hike,Sierra Club, to Mt.Tyndall; meetat Independence, California, 8:00a.m. Saturday (for experiencedback-packers only).August 15Annual Fiesta, LagunaReservation, Albuquerque, NewMexico.August 18-20Cache County Rodeo,Logan, Utah.August 18-20Rodeo, Vernal, Utah.August 24-28 San BernardinoCounty Fair, Victorville, California.Late August Hopi Snake Dances,Mishongnovi andWalpi, Hopi In-dian reservations near Winslow,Arizona. (Date announced bytribal leaders 16 days before dance;check with Winslow Chamber ofCommerce.)

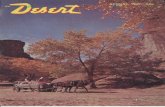

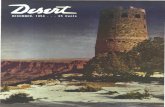

Volume 18 AUGUST,1955 Number 8C O V E RI N D I A N SCALENDAREXPLORATIONFIELD TRIPNATUREC O N T E S TPOETRYH O M E S T E A D I N GDESERT QUIZP H O T O G R A P H YINDIANSEXPERIENCEG A R D E N I N GLETTERSN E W SMININGU R A N I U MLAPIDARYHOBBYCLOSE-UPSFICTIONC O M M E N TB O O K S

"Harvest Time in Canyon de Chelly." Photo byJOSEF MUENCH, Santa Barbara, CaliforniaInter-Tribal Ceremonial at GallupAugust events on the desertThree Days in Devil's Canyon

By RANDALL HENDERSONOpal Miner of Rainbow RidgeBy NELL MURBARGER

Strange Hatcheries for Desert InsectsBy EDMUND C. JAEGER

Picture of the Month contest announcement .Lost Pueblo, andother poemsNatives in my Garden

By CHRISTENA FEAR BARNETT . . . .A test of your desert knowledgePictures of the MonthBan-i-quash Builds a House of Grass

By FRANK A. TINKERBattle of Agua PrietaBy CORDELIA BRINKERHOFF

Flowers That Blossom in AugustBy RUTH REYNOLDS

Comments from Desert's readersFrom here and there on the desertCurrent news of desert minesProgress of the mining boomAmateur GemCutter, by LELANDE QUICK . .Gems and MineralsAbout those whowrite for DesertHard Rock Shorty of Death ValleyJust Between You and Me, by the Editor . . .Reviews of Southwestern Literature . . . .

11161819202223

272930313536404145454647

The Desert Magazine is published monthly by the Desert Press, Inc., Palm Desert,California. Re-entered as second class matter July 17, 1948, at the postoffice at Palm Desert,California, under the Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered No. 358865 in TJ. S. Patent Office,and contents copyrighted 1955 by the Desert Press, Inc. Permission to reproduce contentsmust be secured from the editor in writing.RANDALL HENDERSON, Editor BESS STACY, Business Manager

EVONNE RIDDELL, Circulation ManagerUnsolicited manuscripts and photographs submitted cannot be returned or acknowledgedunless full return postage is enclosed. Desert Magazine assumes no responsibility forrlamage or loss of manuscripts or photographs although due care will be exercised. Sub-scribers should send notice of change of address by the first of the month preceding issue.

SUBSCRIPTION RATESOne Year $3.50 Two Years $6.00Canadian Subscriptions 25c Extra, Foreign 50c Extra

Subscriptions to Army Personnel Outside U. S. A. Must Be Mailed in Conformity WithP. O. D. Order No. 19687

Address Correspondence to Desert Magazine, I*alm I>esert, California

A U G U S T , 1955

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

4/48

Sometimes it was necessary to strip and wade to keepthe packs and camera equipment dry. There was no trail just rocks, and occasionally heavybrush. The rope was used many times.

Three Days in Devil's CanyonSlashing through the heart of the San Pedro Martyr Mountains inLower California is the Devil's CanyonCanyon del Diablo, the Mexi-

cans call it. Curious to know why the padres, the prospectors and thecattlemen have all by-passed this canyon down through the years,Randall Henderson and two companions spent three days traversingthe 22-mile bottom of the chasmand this is the story of what theyfound there.By RANDALL HENDERSONMap by Nor ton Al len

Valley on the desert side of the SanPedro Martyr Range, we had beenscaling rocks and fighting our waythrough thickets of catsclaw, agave andmanzanita for three days to reach thispeak.While there was good visibility for75 miles in every direction, my interestwas attracted to the deep gorge im-mediately below us on the west sideof the San Pedro MartyrsCanyondel Diablo. This great gorge drains

ONE April afternoon in1937 Norman Clyde and I stoodon the 10,136-foot summit ofPicacho del Diablo, highest peak onthe Baja California peninsula (DesertMagazine, Jan. '53 ) . To the east wecould see across the Gulf of Californiato the Sonora coastline, and to thewest the sun was just dipping belowthe horizon where the sky meets thePacific Ocean.Starting from the floor of San Felipe

the western slope of the upper Martyrsand then cuts a great semi-circular gashthrough the range and dumps its floodwaterswhen there are cloudburstsinto the San Felipe Valley on the des-ert side. The mouth of the canyon isonly 12 miles north of ProvidenciaCanyon up which Norman Clyde andI had climbed to the summit of ElDiablo peak.It is a magnificent canyonand Iresolved that some day I would tra-verse its depths. Perhap s there was agood reason why the Mexicans hadnamed it El DiabloThe Devil.It was 17 years before I went backto Canyon del Diab lo. Aries Adam sand Bill Sherrill and I had sat aroundour campfires on desert exploring tripsand many times discussed plans forthe descent of this canyon, but it wasnot until October, 1954. that the tripwas scheduled. Aries secured a week's

D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

5/48

leave of absence from the hemp strawprocessing mill in El Centra where heis superintendent, and Bill wrangled aweek's vacation from the U. S. BorderPatrol at Calexico where he was chiefand we took off for the San PedroMartyrs.My brother Carl drove us down thecoastal highway from Tijuana throughEnsenada to the end of the 142-milepaved road which follows the Pacificshoreline, and then another 36 milesover hard but rough dirt and gravelroad to the San Jose Ranch of Albertaand Salvador Meling which was to bethe starting point for our trip acrossthe peninsula by way of the Devil'sCanyon.For years I have looked forwardto meeting the Melings. I wonderedwhy they had chosen to spend theirlivesthey are both past 60 in thisremote semi-arid wilderness of BajaCalifornia. Neither of them is of Mexi-can descent.

Harry Johnson, Mrs. Meling's father,brought his family from Texas to BajaCalifornia in 1899 when Alberta wasa small girl. Johnson was a frontiers-man of the finest type . A t first he hada ranch near the coast at which is nowSan Antonio del Mar, 150 miles southof San Diego.Then he became interested in therich placer diggings at Socorro nearthe base of the San Pedro Martyr

Range, 40 miles inland from his ranch.Gold had been discovered there in1874, and the gravel was worked inter-mittently until Johnson acquired theground . He operated the mines 15years, until they were worked out.Salvador Meling came to LowerCalifornia from Norway with his par-ents and eight brother s in 1 908. Theywere miners, and worked for Johnsonat the placer field. Eventually Salva-dor married the boss ' daughterandthey have made their home in the vi-cinity ever since. They have four grownchildren and 12 grandc hildren. Oneof the daughters, Ada Barre, managesthe guest accommodations at the SanJose ranch.

The Melings run between 400 and500 head of cattle on their range, andhave a crew of Mexican cowboys whoalso serve as dude wranglers whenthere are guests at the ranch.They drive 112 miles to Ensenada

Above Aries Adams, SalvadorMeling and Bill Sherrill at the SanJose Ranch.Center Juanito and Adolfo, guidesand packers for the expedition.Below Home of the Melings theSan Jose Ranch near the base of theSan Pedro Martyr Mountains.

A U G U S T , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

6/48

o . > o 7 ^ " ' ; ?' 'yj? ji ''"""iL. ''-. ^ iM%il^M0ff$:f-J~J- V . ' - . " P o t r e r o ; i '.:^ , / 5^fe'. .... ' -' ^J - '

V .La Grul la

twice a month for mail and for suchessential supplies as sugar, coffee, salt,flour, fuel oil and tank gas. Most oftheir food comes from the ranch. Afine spring equipped with a jet pumpsupplies irrigation w ater for an orchardof apples, peaches, pears, plums andgrapes, and for their garden. Theyraise their own meat and vegetables.Mrs. Meling took me into the store-room where the shelves were stackedwith 600 jars of fruit, jam, jelly andvegetables which she and her Mexicanmaids had canned. They have a smokehouse to cure their meat, and Mrs.Meling bakes from 40 to 50 loaves ofbread a week to supply the ranchcrew and guests.Salvador manages the ranch and

orchards and gardens. San Jose is aquiet retreat shaded by huge cotton-wood trees, with limited guest accom-modations. The family style mealsare homegrown and homemade, andthe platters are filled high with foodthat has never been inside of a canneryor processing factory.We reached the Meling ranch latein theafternoon andarranged forpack-er s and saddle horses for the 42-mileride to upper Diablo Canyon, to startthe next morning.Talking with Alberta by the hugefireplace that evening I began to un-derstand why they had chosen to re-main at this isolated Baja Californiaoasis. What I learned merely confirmedwhat Arthur W. North had written

about her in Camp and Camino inLower California (now out of print )when he knew her there as a girl 50years ago. He referred to her as MissBertie, for that was the name by whichshe has always been known amongfriends and neighbors. Quoting fromone of Miss Bertie's neighbors, Northwrote:"She's the most interesting person-ality in all this countrysideand yet1 can't describe her. Though she haslived in these wilds since babyhood,she has the gentle traits you mayfindin the girls at home. And 1 must tellyou about her pluck. Once during theabsence of her men folks, she heardthat some marauding Indians and Mex-icans were about to take off with abunch of her father's range cattle.Without pausing for rest or givingthought to the risk, she rode 13hours ;indeed, using up two saddle horses,

the range riding was so rough. Shesaved the cattle. Another time she wasin San Diego with her father. A manof considerable means, he pointed outa magnificent eastern-style residenceto her, saying. 'Bertie, yougirls mu stn'tremain Amazons. I think I'll buy thatplace for you.' Sheknew he might bein earnest. 'Oh, youwouldn't make uslive in the city,' she cried. 'Town lifemust be so crowded. Can't we livealways in the sierras? There we canbreathe. ' "For 17 years 1 have been trying to

gain information about Canyon delDiablo. Members of the Sierra Clubhad climbed down into the gorge andout again, on their way to the top ofDiablo peak. They had found waterthere, but knew nothing about the can-yon below. At Mexicali and San Fe-lipe andEnsenada I hadmade inquiriesabout El Diabloand the answer in-variably was shrug and "Quien Sabe."No one at San Jose ranch had everbeen through the canyon. AlbertaMeling said: "I'venever known any-on e whowent down the canyon. I'vealways wanted to make the t rip, butit is too rough for the horses, and wenever seemed to have time for it. Ihave been told there are Indian petro-glyphs and a waterfall at the SanFelipeValley entrance, but that is all I knowabout it."A rough road continues 11 milesbeyond the ranch to the old Socorroplacer field, and since it would be pos-sible to drive the jeep station wagonto that point, we arranged for thepackers to meet us there with thehorsesthe following morning. We had esti-mated the ride from San Jose to Diabloat two days, and the distance downthe canyon to its portal on the desertat from 20 to 25 miles. We had al-lowed for three days in the gorge.San Jose ranch is at an elevation of

DESERT MAGAZINE

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

7/48

2200 feet, and the mine road climbedanother 2000 feet to a point just be-yond Socorro where the going becametoo rough even for the jeep. We wereon an old road bulldozed several yearsago by a group of men who thoughtthey had a concession to cut big tim-ber up on the San Pedro Martyrs. Butthe Mexican government never actu-ally issued the permit, and flood waterhas now cut great gullies in the road.Nothing remains at the old placercamp today except heaps of adobepartly concealed by the desert shrub-berymarking the sites of the housesonce occupied by Johnson's miners.It was nearly noon when Juanito andAdolfo, the packers, caught up withus. In the meantime Carl had depos-ited us along the old road, and withhis ferry job completed he returnedover the coast highway to California.The western approach to the SanPedro Martyrs is over rolling hills cov-ered with ribbon wood, juniper, man-zanita, mountain mahogany, laurel andsage. At the higher levels are fernsand coniferous trees including finestands of Ponderosa pine.At three o'clock our little pack trainhad reached big timber, and a halfhour later we camped at the edge ofa lovely pine-fringed mountain meadowwith three springs close by. This isLa Coronaat an elevation of 7100feet.That evening at La Corona camp Ihad my first Kam p-Pack m eal. TheKamp-Pack brand covers a wide rangeof dehydrated and seasoned food prod-ucts made by the Bernard Food Indus-tries at 1208 E. San Antonio St., SanJose, California, for camping and back-packing trips. "Nothin g to add butwater," is the slogan on each package.Ground or powdered meats, fruitsand vegetables come in moisture proofenvelops of meta l foil. They are pack -aged in 4-man and 8-tnan portions.For this trip I ordered 4-man portions

to last five days 60 me als. The totalweight was 11 pounds, and the cost$17.79. Our camp menu includedsuch items as chicken pot pie with bis-cuits, chicken stew, cheese-egg ome-lette, hamburger steak and meat loaf,mashed potatoes with chicken gravy,Boston baked beans, scrambled eggsand buttermilk pancakeswith coffee,chocolate and powdered milk, andapplesauce or pudding for dessert.It was necessary only for each ofus to carry a small kit of aluminumutensils for cooking and eatingand

at mealtime we enjoyed all the luxuriesof hom e. It was surprising how thosesmall crumbs of dehydrated chickenbecame tender and delicious morselsof meat after the proper cooking andheating. Th at really is camping deluxe.

Alberta M eling of San Jose Ranch in Baja California. Her postoffice is112 miles away at Ensenada and the road is not all paved.We spread our sleeping bags on bedsof pine needles that night. We ca r-ried no firearms, but Bill Sherrill hadbrought along one of those wild animalcalls. It is a tin gadget like a whistlewhich sounds like a beast in great dis-tressI was never able to figure out

just which beast. The theory is thatif you make a noise like a woundedfawn or baby eagle, the carniverousanimals of the forest will all come infor a mea l. So, after dark we went outin the forest and made some hideous

noises. It wa sn't a big success. Billand Aries were sure they saw a foxlurking among the trees, and oncethere was an answering call whichcould have been a cougar. A pro -longed drouth has left San PedroMartyrs very dry, and the Mexicanboys said most of the deer and otheranimals had gone elsewhere.

We were away at 7:30 in the morn-ing. Our trail led through a silent for-est of conifers, ascending and descend-ing the easy slopes of a high plateau,A U G U S T , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

8/48

always gaining altkude. Once the soli-tude was broken by a cracking andsplintering sound, and we turned inour saddles to see an aged Ponderosagiant topple to the ground. A cloudof dust filled the airand that was all.We had witnessed the final passing ofa tree which probably was in its primewhen the Jesuit padres were buildingtheir missions on the Baja Californiapeninsula.It is at the base and in the canyonsof the San Pedro Martyrs that treasurehunters for many years have beenseeking the fabled lost gold and silverof the Santa Ysabel missiona cachewhich is said to have been concealedby the Jesuit Black Robes when theywere expelled from New Spain in 1767.Occasionally through the pine treeswe would get a glimpse of the whitegranite peak of Picacho del Diablo

far to the east, the landmark towardwhich we were traveling.At 11 o'clock we reached Vallecitos,a series of high mountain meadows.Our trail ended at an old log cabinwhich Juanito told us was used oc-casionally by cowboys and sheep herd-ers. Our guide said there was a springa half mile off the trail, but the rimof Diablo Canyon is but three or fourmiles from this point and we felt wehad ample water to complete the jour-ney.At Vallecitos, Juanito turned toward

the south and we rode for six miles ina southerly direction parallel to DiabloCanyon. We had told the Melings wewanted to go to the rim of upper Di-ablo Canyon by the most direct route,and we assumed Juanito understoodthis. But either he misunderstood hisdirections, or was not familiar with theterrain, for he finally brought us tothe summit of an unnamed peak atthe head of the canyonat an eleva-tion of 9510 feet. We were on a saddlewhere the timbered slopes to the northof us drained down into Diablo gorge,and the arid canyon on the other sidedrained into the desert below SanFelipe. The blue waters of the gulfwere only a few miles away.

After leaving Vallecitos, instead ofgoing to the rim of the canyon at itsnearest point, Juanito had taken usperhaps ten miles further in a south-easterly direction to the very head ofthe canyon. All of which would nothave been disturbing were it not forthe fact that we had used the last ofour water when we stopped for a trail-side lunch and we now faced theprospect of working our way downprecipitous slopes to an elevation per-haps 2500 feet below, before we couldquench our thirst in Diablo Creek.Since Juanito understood no English,we waved him farewell and he turned

back over the trail with his pack traintoward the San Jose ranch.Now we were on our own. Ourpacks were not excessive. We hadweighed them at San Jose. Bill wascarrying 31 pounds, Aries 28, and mineweighed 26. The difference was in thebedding, clothing and camera equip-ment. Bill carried a light plastic airmattress. We also carried 100 feet ofhalf-inch Nylon rope which added fourand one-half pounds. We took two-hour turns with the rope.It was 2:45 Wednesday afternoonwhen we shouldered our packs andstarted down the steep slope, much ofthe time lowering ourselves with handholds on trees and rocks. We wel-comed the shade of the pine trees whichgrew on the mountainside. We were

FOOD FOR BACKPACKERSFor those who take long tramps ondesert or mountains with their beds andgrub in the packs on their backs, theadvantage of dehydrated foods is wellknown. One pound of dried onions isequivalent to nine pounds of fresh on-ions. Other vegetables are about thesame 9-to-l. The ratio is slightly lowerfor meats, and many times higher fordrinks such as coffee, milk, fruit juices,malted milks, etc.Whole milk powder serves for multi-ple purposes: For cereals, meat gravy,pancakes, hot chocolate, milk shakesand puddings.While Kamp-Pack foods are offeredin kits the complete day's food breakfast, lunch and dinner for four or

eight menthere is considerable econ-omy, and a more selective menu ifordered a la cartethat is four or eight-man packs of the items desired. If onlytwo persons are on the trip the extrafood need not be wasted, as the metalfoil envelopes in which it comes maybe closed and the extra portions readilycarried over for a future meal.Members of the Diablo Canyon expe-dition described the flavoring of thefoods as "delicious." Their only sug-gestion was that some of the items werebetter if soaked in water somewhatlonger than the directions required,before cooking.

thirsty and we had no way of reckon-ing the distance to water. Within anhour the sun disappeared over the westrim above and by five o'clock it wasdusk and we made camp for the night.For sleeping quarters we scooped outlittle shelves between rocks on the side-hilland went to bed without supper.Food that bore labels "Nothing to addbut water" was of little use to us then.We were away at five in the morn-ing without breakfastconfident thatbefore many hours we would come towater. At mid-morning we had to un-coil the rope to lower our packs overa 60-foot dry waterfall, and then fol-lowed them down hand and toe. Wewere feeling the effects of dehydration,and worked down the rock face withextra caution.

And then, just at 12, we arrived atthe top of another dry fall and couldhear the trickle of water at its base.Aries and Bill detoured the fall while Iuncoiled the rope and rappelled downthe 40-foot face to a spring of coldwater. The elevation was 6700 feet.One of the packages in the Kamp-

Pack was labelled "'Strawberry MilkShake" and there was a combinationmeasuring cup and shaker in the kit.What a feast we had there by that ice-cold springwith milk shakes as richand flavorful as you buy at any sodafountain. After a refreshing two hoursthere at the headwaters of DiabloCreek we had forgotten the discom-fort of 24 hours without water andwere eager to see what was ahead.From that point we tramped besideflowing water all the way down thecanyon, crossing and re-crossing it ahundred times a day.It was never smooth going, but wehad rubber-soled shoes to insure goodfooting on the smooth granite. Manytimes we had to lower ourselves byhand and toe, but there were no diffi-cult passages that afternoon.A short distance below the springwe found the charred wood of a deadcampfire, and a can of fuel oil for aprimus stove. I assumed this was theplace where one of the Sierra Clubexpeditions had camped when theyfound it necessary to drop down into

Diablo Canyon as they climbed Pica-cho del Diablo from the west. Thepeak was directly above us, a 4000-foot climb from here.Between 6500 and 6000 feet therewere ducks on the rocks to mark aroute along the floor of the gorge. Be-low that point we found no evidence ofprevious visitors, either Indians orwhites, until we reached the 4000-footlevel.At four o'clock the canyon hadwidened somewhat and the floor wascovered with a forest of oak trees. We

found a comfortable campsite besidethe stream with a cushion of oak leavesfor our beds. For supper we hadchicken stew and pan fried biscuits.The elevation was 5900 feet.We were tired tonight, physicallyand mentally physically, becausenone of us was conditioned for a longday with packs. Mentally because ofthe decisions thousands of them.Traveling with packs over more orless loose boulders, every step calls fora decision, and when the descent isover vertical rock, every foot and hand-

hold has to be tested and an instinc-tive decision made for every hold. Themind literally becomes weary makingdecisions. We were conscious alwaysof the difficulties which would be en-tailed if a careless step on a loose rock8 DESERT MAGA ZINE

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

9/48

Up to the point of extreme exhaus-a journey. There were compen-

led us into an impenetrableur steps. Once I thought I was smarterhan the leaderand stayed on theight side of the stream instead of fol-ther side. My folly led me into aittle swamp where I spent 30 minutesclawing my way through fern frondsigher than my head.

Below the oak forest we encounteredense thickets of underbrushagave,atsclaw, wild grape, scrub mesquiteand ferns.The canyon became more precipi-tous and several times we lowered ourdown over slick waterfalls.At five o'clock we made camp at the4300-foot level and slept on a sandbarthat night. Th e walls of the gorge rosealmost verticle on both sides of us. Wehad expected to be out of the canyonthe following day, Saturday, but itseemed we were still in the heart of therange, and we were beginning to havedoubts that we would make it on sched-ule.

We were up at five and had scram-bled eggs for breakfa st. Th e canyonwas dropping rapidly and we con-stantly scrambled over and aroundhuge boulders . Ho we ver, we pre - ||*fcferred the rocks to the thorny brush ;;.of the previous day, and mad e good , \e-time. ' < * ' ' ' 'At noon the canyon had turned Isharply to the east and was beginning to open up. We ate lunch at 3000 feet. H The temperature was 82 degreeswewere getting close to the desert.

Above During the 42-mile ridefrom San Jose Ranch to Canyon delDiablo we caught an occasionalglimpse of El Picacho del Diablothrough the trees. T he right of thetwin peaks is the highest 10,136feet Baja California's highest peak.Center The western slope of theSan Pedro Martyrs is a land of roll-ing hills, big timber and mountainmeadow s. Pack train enroute toCanyon del Diablo.Below Bill Sherrill and AriesAdam s stopped for a refreshing drinkat one of the many pools in the bot-tom of the canyon.

A U G U S T , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

10/48

"We swam the last 40 feet of the canyon" in the pool on the left. These pools atthe desert mouth of the canyon, walled in by slick rock, have been an almostimpassable bar rier to those who wou ld enter El Diablo from below.Late in the afternoon we found moreducks on the rocks, and other evidencethat some one had been up the canyonrecently. Then we came to a pool withvertical slick rock walls and had tostrip and wade breast deep in the water.Around the next bend was another poolat the foot of a 3-foot w aterfall. Th ewater was deep. A detour over theridge on either side would have re-quired hours of hard climbing. Thesun was going down, and we weretired. Aries stripped and dived in andswam the 40 feet to the far side of thepoo l. T o get our cam eras and duffleacross we rigged an overhead tramwaywith the rope and when everything wasacross Bill and I plunged in and swam.A quarter of a mile below this point,just as it was getting dusk, we emergedsuddenly from the walls of the gorge,and a few minutes later were met by

Aries' son, Jack Adams and his friendWalker Woolever, who had brought ajeep down from El Centra to meet us.Jack and Walker had arrived earlier inthe day, had driven their jeep as nearthe canyon entrance as possible and

then made their way up the canyon andleft the ducks we had seen late in theafternoon. They had scaled that lastwaterfall by using a shoulder stand, oneof them submerged in seven feet ofwater while the other climbed the fallfrom his shoulders, and then gave ahelping hand from above. Only acouple of venturesome teen-agerswould have attempted such a feat.The deep pool and waterfall are bar-riers which probably more than anyother factors have left Devil's Canyonvirtually unexplored down through theyears. There are petroglyphs on therock walls below the pool, but in the22-mile descent of the canyon we hadseen no evidence that Indians had everbeen thereno shards, no glyphs ormetates, flint chips, sea shells or smoke-charred caves. Even more strange isthe fact that although wild palms ofthe Erythea armata and Washingtoniafilifera species grow in the desert can-yons both in the Sierra Juarez rangeto the north and in the San PedroMartyrs south of us, we found not asingle palm tree along the way.

That waterfall barrier at the mouthof the canyon probably explains thelack of palm tre es. M ost of the wildpalms in the canyons of the Southwestgrew from seeds brought there by In-dians, or in the dun g of coyotes. FewIndians and no coyotes have ever sur-mounted that pool and waterfall I amsure.From the mouth of the canyon wehiked a mile to the jeep and then fol-lowed a rough road across San FelipeValley and through a pass at the northend of Sierra San Felipe and homeover the paved road that extends fromMexicali to the fishing village of SanFelipe on the gulf.

Why did they name it Canyon delDiablo? I do not know for sure, butI can bear witness that we were as dryas the furnaces of Hades going in, andas wet as if we had swam the RiverStyx coming out.It is one of those expeditions I wouldnot want to repeatand will alwaysbe glad I did it once.

1Q D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

11/48

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

12/48

an d Dad and Mother were coming upto the mine; and if this was even halfas good as I thought it might be, Iwanted them and Agnes to be in onthe 'kill' . . ."Leaving the rock still embedded inthe chill tomb where it had lain throughno-one-knows-how-many million years,

Keith had walked out through the tun-ne l a little shakily, perhaps; andmaybe he was a little more carefulthan usual that night when he pad-locked the heavy plank door thatguards the portal of the mine."For some reason I didn't seem towant any supper," he said. "And after1 got to bed, and the cabin was darkand quiet, I still couldn't go to sleep."Father 's Day, and the Hodsons wereback in the tunnel Keith and hiswife, and Keith's mother and dad. Withan ice pick and a screwdriver Keith

an d his father were exhuming that pieceof rock; and I wouldn't be at all sur-prised if their hands were trembling alittle, and their fingers seemed to beall thumbs; and maybe there was sortof an unspoken prayer in their hearts.And then, after nearly a full day'slabor, The Rock had been lifted freeof its enveloping clay, and everyonewas looking at it and smoothing hishands over it, caressingly and unbe-lievingly. First they would look at TheRock, and then at one another, halfscared like; and no one was sayingvery much, because there was nothinganyone could say that would have beenworthy of that particular moment.

The Rock was about nine incheslong and half as broad, and weighed

around seven pounds. But the Hodsonsweren't breaking it down mentally intograms and carats, and appraising it indollars. Not then, they weren't.They were just staring down intothat stone and seeing a pale, blue trans-lucent world shot through with livingflames of red and green, and rose and

yellowlike smoldering embers float-ing in a bottomless well!And, suddenly, they realized thatthe old mine tunnel no longer seemeddark or cold; or the labor of mining,hard and unrewarding. In one match-less moment, by the magic of one pieceof rock, all that had been changed;and four persons who had entered thetunnel as common earth-beings, wereleaving it as godlings, walking with thegods.Godlings? Wh at could a mere god-ling ever do that would lift him to the

exalted plane of an opal miner who hasjust taken from his own ground thelargest precious opal ever known toman!This world's largest opal, discoveredby Keith Hodson in June , 1952, wasno t the first great stone that had beenyielded by the Rainbow Ridge mine,in Humboldt County, Nevada.First of several incomparable gemsto come from that same tunnel hadbeen a magnificent black opal withvivid flashings of multi-colored fire.Purchased by Col. Washington A.

Roebling, builder of the BrooklynBridge, this earlier stone had been pre-sented in 1926 to the Smithsonian In-stitution, where a tentative valuationof $250,000 had been placed upon it.

Weighing 2665 carats around 18ouncesthe so-cal led "Roebling Opal"had been characterized as the largestblack opal in the world.A nd now, 33 years later, the minethat had produced The Roebling hadyielded this second magnificent stone a gem nearly seven times as huge

as its predecessor!Original discovery of opals in Ne-vada's Virgin Valley is credited to arider on the Miller & Lux ranch, about1906. Other stones were picked up,from time to time; and as word ofthose discoveries reached the outsideworld, a few prospectors strayed intothe region, and many claims were filed.First official recognition of the newfield was that accorded by J. C. Mer-riam, whose report on the area ap-peared in the publication Science (Vol.26, 1907, pp. 380 -382 .) Annu al year-

books of the U. S. Department of theInterior, dealing with mineral resourcesof the United States, in 1909 begancarrying reports on the Virgin Valleyopal deposits. With each year follow-ing, these official releases became moreglowing and employed the use of moreextravagant adjectives, and with thereport of 1912 it was declared that inbrilliancy of fire and color, the VirginValley's gem opal was unexcelled bythat from any other locality in theworld.This sanguine report, quite naturally,

brought into the valley a renewed flurryof prospecting, and opal claims werestaked on every likely and unlikelyspot of ground. Of the scores of claimsfiled, only a few were developed into

O R E G O NI; X \ N , E V 'A D

r RAINBOW RIDGE 'OPAL MINE

ToWINNEMUCCAIOO Mi iromDemo

12 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

13/48

ftp

Keith Hodson and Ed Green of Lovelock, Nevada,examine one of the opals from the famous mine. Agnes Hodson holds in her hands the world's largestopal taken from the Hodson's mine in the VirginValley area.commercial producers; and of those sodeveloped, the foremost for more than40 years has been the famous RainbowRidge, now owned by Keith and AgnesHodson.In 1946, immediately after Keithwas mustered out of the Army, he andhis family had located at Mina, inMineral County, Nevada, where hehad begun development work on sev-eral turquoise claims which they stillown there.

"Dad and Mother, who live at Ev-ansville, Indiana, have been gem col-lectors for mo re than 15 years . All ofus, naturally, had heard many thingsabout Virgin Valley; and when thefolks came West on their vacation, in1947, Dad was determined to comeup here 'and buy a couple of opals. 'But instead of buying a couple of caratsand letting it go at that," he grinned,"we had to go and buy the wholemine!"When the Hodsons and their twosmall children, Sharon and Bryan, tookup residence in an old stone cabin atRainbow Ridge, they achieved the ul-timate in getting away from it all.City dwellers since birth, they sud-denly found themselves living five milesfrom the nearest water; 40 miles from

the nearest mail box; 80 miles, overunpaved roads, from the nearest drugstore (and that in a village of only 600inhabitants); and 140 miles from Win-nemucca, their county seat.Along with adjusting themselves tothis extreme out-of-the-wayness, anddesert living in general, the Hodsonsbegan learning immediately the hardfacts of an opal miner's life.They learned that the only powertool admissible to use in an opal mineis a so-called "clay digger," operatedby compressed air; that even this toolmust be used with caution, and only indead areas, where no gems are believedto exist. Blasting, they learned, is tabooat every stage of the operatio n. Theyfound that as many as 30 days of hardlabor might be expended without bring-ing to light a single carat of gem opal;and they discovered that claim jump-ing and highgrading are forms of pri-vate enterprise that did not pass fromexistence with gold rush days.During their indoctrination they alsolearned that while summer tempera-tures in the valley may soar to morethan 100 degrees, winter, at this eleva-tion of 5400 feet, brings frigid weatherand high winds that drift snow todepths of eight and 10 feet, and may

block ingress roads for weeks at atime.Being young and enthusiastic andthoroughly enamoured of opals, theHodsons found it possible to take intheir stride all such disquieting details.Strangely enough, the toughest pillthey have had to swallow is embodiedin a certain refrain tossed at them fromalmost the hour of their arrival at Rain-bow Ridge."Virgin Valley opals are beautifulas any in the world," runs that refrain."But they won't cut!"Hearing this statement, Keith Hod-son comes near to forgetting his school-ing in the art of self control."Virgin Valley opals," he asserts,"will cut! Jus t because no one haslearned to cut them successfully,doesn't mean we'll never learn! W e'reworking on the problem, almost nightand day and other lapidaries areworking, too. Some time," he declares,"we'll discover how to do it!"

The opal's tendency to fracture isnot confined to stones from the VirginValley, but is a detail that has besetgem cutters since the time of Caesarthe same trouble that now faces thecutter of Nevada opals, having onceplagued the ancient lapidaries as theyA U G U S T , 1 9 5 5 13

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

14/48

worked on the magnificent gems ofcentral Europe, and later on the opalsof Australia and Mexico.With increased knowledge of gemcutting, it was realized that as compo-sition of the opal differed from that ofother gemstones, so a different methodmust be developed for their cutting.While most other gems are crystal-lized, the opal is formed of a moltenhydrous silica containing from 6 to 10percent of water. In the process ofcooling and congealing, it is contendedby some mineralogists, this moltensilica cracked and separated into mi-nute sections which later refilled witha similar silica-jell, thereby restoringthe stone to apparent solidity.In these refilled cracks possibly liesthe secret of the opal's "fire"; but itmay also be these cracks that are re-sponsible for a peculiar stress that fre-

quently causes an opal to explodewhen subjected to the friction heat ofthe lapidary wheel.After ruining thousands of carats ofmagnificent stones, gemcutters gradu-ally developed methods whereby opalsfrom Europe, Australia and Mexicomay be cut with comparatively littleloss from fracturing."While none of the Old Worldmethods have proven completely satis-factory in working our Virgin Valleyopals, I'm confident there is some wayin which these stones may be cut suc-

cessfully," declared Keith. "Whenwe've learned the answer to this prob-lem, our Rainbow Ridge gems willrank with the finest the world pro-duces!"Until that time, the chief value ofVirgin Valley opals will continue tolie in the field of cabinet specimens.Even for this purpose it is recom-mended that the stones be preserved inliquid, since exhaustion of the naturalmoisture imprisoned in the opal hasa tendency to induce deterioration ofthe piece.Despite thepopular notion that spe-cimen opals should be preserved inglycerine, theHodsons object to use ofthis solution in its undiluted statea50-50 combination of glycerine andwater, or even straight water, beingpreferable, they believe. (The Hod-son's seven-pound prize opal is housedin a custom-built, sponge-padded tank,containing straight water.) But for thefact that immersion in any oil-basesolution precludes later use of the gemsin plastic work, Keith considers min-eral oil or baby oil the ideal preserva-

tive for specimen opals.Other misconceptions attached tothis gemstone, said Keith, include thegenerally-held belief that opal is aform of petrified wood.Precious opal of the Virgin Valley,

it was explained, is not a petrifactionin any sense; but, rather, a cast thatresulted when empty pockets in theclay became filled with molten silica.The entire Virgin Valley, geologyshows, was formerly covered by a greatlake, or inland sea. Onthe hills b order-ing this lake and its tributary streamsgrew a wide variety of conifers, includ-ing some species very similar to ourpresent-day spruce. As branches andother dead wood from these trees fellinto the streams, it was carried down-ward to the lake, there to be washedup on the shores as driftwood.

Time passed; geologic changes tookplace; and those lake beaches andtheir driftwood eventually were buriedbeneath many feet of volcanic ash orother matter. Of that entombed wood,some petrified, and some rotted away;and due to the nature of the envelopingmaterial, that which rotted left its or-iginal form preserved perfectly in theenfolding clay.

Came more eons, and cataclysmicdisturbances; and, eventually, molten

The world's largest opal, atlatest reports, is being preservedin a custom-built tank somewhatresembling an aquarium bowl,padded with sponges above andbelow. The Hodsons have receivedsubstantial offers for it, but sinceno way has yet been found to cutthis type of opal it is a museumspecimen rather than a commer-cial stone, and is valued accord-ingly-

silica wasbeing forced under pressurethrough the earth's crust. Wh ereverthat silica encountered a bit of un-filled space, it flowed into that nicheand congealed. In cases where thatunfilled space had resulted from beachwood that had rotted out, leaving itsform preserved in the clay, the in-flowing silica took the identical shapeof that form, in the same mannergelatin takes the shape of its mold.

"But because an opal has assumedall the characteristics of a twig or sec-tion of tree limb including bark,knots, and even lateral branchesmostfolks are convinced it's a petrifaction,and they won't have it anyother way!"said Keith.Conifer cones, occasionally encount-ered in the opal beds, are the specialjoy of Agnes Hodson who has collectednearly 50 of them. Most of these

cones are not gemopal, but true pet-rifactionsbeing naturally brown incolor, and nearly perfect in appearance."One day a rockhound who hadbeen working our dump, came in withthe largest petrified cone wehave ever

seen," recalled Agnes. "It was morethan three inches long and perfect inevery detail even the individualbracts were perfectly represented. Andwould you believe itthat man wasdetermined he was going to break thatcone open to see what was inside it!"Keith said, 'For heaven's sake, man,

don't ruin that wonderful specimen!We'll give you a $50opal for i tbutdon't break it!' He wouldn't t rade itfo r the opal Keith offered him, andwhen he started back toward his carhe was still fingering his rock hammer,and turning the cone over in his hand,an d we could see he was still set onthe idea of 'busting' it open!"Due to pressure of popular demand,the Hodsons have relaxed their formerrestrictions and are again permittingrockhounds to work their opal dumpon payment of three dollars a day.

While the dump has been gleaned fora number of years there are smallpieces of precious opal still to be foundthere; and the matchless thrill of find-ing even a tiny gem fragment is enoughto keep an opal enthusiast searchingthe ground for hours at a time.How much precious opal has beentaken from the Virgin Valley in thepast 50years is any man's guess;par-ticularly so, in view of the large quan-tities sold by highgraders, claim jump-ers, and others who kept no record ofproduction. Only two mines the

Rainbow Ridge and Mark Foster 'sBonanza, recently purchased by theHodsons have been worked on alarge scale. Of these, the more exten-sively developed is theRainbow Ridge,which comprises six patented claimsof 20 acres each, with around 1000feet of tunneling.In the course of its career, this minehas passed through a succession ofhands; but of all its owners, none lefton the valley an impression more in-delible than that bequeathed by Mrs.Flora Haines Loughead.Flora Loughead, in 1910, was awoman in hermiddle 50s. For 30-oddyears she hadbeen a staff writer on theSan Francisco Chronicle; and withthese new opal fields inNevada attract-ing attention as the first impo rtant opaldeposits ever found in the UnitedStates, she had been given an assign-ment to go to the valley and write thestory for her paper.Mrs . Loughead went to the valleyand completed her assignment. Butthat wasn't all.While there she became such an opalenthusiast that she bought the RainbowRidge property and proceeded to throwherself, heart and soul, into the devel-opment of those claims."Strangely enough," said Keith, "sheseemed to have a perfect flair for min-ing! As one example, she ran a new

14 DESERT MAGAZINE

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

15/48

tunnelby dead reckoningto inter-sect with an existing tunne l. And soperfectly did she engineer the job thather newly-run tunnel hit the old driftwithin six inches of the place she hadplanned to hit it!"Mrs . Loughead had three sons Victor, a writer on technical subjects;and Allan and Malcomb, who took adim view of opal mining and tinkeredold automobiles by preference. Whenthey had grown weary explaining howtheir surname, Loughead, should bespelled and pronounced, the boys hadadopted the phonetic spelling of thatname Lockheed. They subsequentlyfounded the Lockheed Aircraft Cor-porationin part, at least, with fundsderived from Virgin Valley opalsand went on to amass fame and for-tune.Their mother, however, had stuck toher original name of Loughead, andto opals. Fo r nearly a third of a cen-turyuntil the end of her dayssheremained a zealous devotee of thesefire-flashing gems; and when well pastthe 80-year mark and grown quite en-feebled, Virgin Valleyans still recallhow she would slip away from herfamily and her California home, andreturn to Rainbow Ridge to supervisework on her mine.Death came to this strange woman,in 1943, at the age of 87 years; buteven today, her indomitable spirit goesmarching through the valley. No m at-ter where I turned for informationwhether to Keith and Agnes Hodson,or Mark Foster, or to Mr. or Mrs.Murial Jacobsit seemed to be onlya matter of moments until every con-versation would introduce the nameof Flora Loughead.We remained in the valley threedays. Keith took us into the tunnelordinarily forbidden territory to visitorsand initiated us into the secrets ofopal mining. We also spent a fewhours working the dump and foundsome tiny fire-flashing fragments to bepreserved in vials of water and addedto our growing collection of specimens.And, along with other things, welearned that while opal is the stellarattraction of this little known region,it is far from being the sole attraction.Petrified woodsome of fairly goodpolishing qualityis plentiful through-out the area. M rs. Jacobs even toldus of one stump in the Virgin Valleybadlands, ten feet in diameter and ap-parently caught midway between woodand stone. Some parts of the stump,she said, are still so wood-like in ap-pearance that early settlers tried toburn the material in their cookstoves*Another point of interest to rock-hounds is a seam of pale yellow opalon the Virgin Valley ranch, about fourmiles from Rainbow Ridge. This ma-

. . ! - i . - : ' . " * . - . * ' > " . v v . * - . : ''

"The Castle," eroded from hardened volcanic ash on the Virgin Valleyarea of Nevada.terial, we found, fluoresces a vividgreen and whets the interest of a Geigercounter.It would be difficult to imagine onearea with more diversified attractionsthan those offered by the Virgin Valleyand its environsnot only for rock-hounds, but for bird students, colorphotographers, historians, explorers,and general devotees of the Wide BlueYonder.There are, however, a few facts thatshould be borne in mind by potentialvisitors.First, it should be remembered thatthe valley is not an all-year vacationland. Best time to visit the region, ac-cording to Keith, is during the latterpart of June and early July; and fromlate August, through September, andoccasionally into Octo ber. During thisperiod the weather is at its best. As

shaded campsites arc virtually non-existent in the area, the middle sixweeks of summer are generally too hotfor camping comfort; while winterbrings snow, wind, and blocked roads.One more item should be kept inmind by potential visitorsand this isimportant! No supplies or transientaccommodations are available any-where in the valley. Closest supplypoints for either groceries or gasolineare Denio, 38 miles east, and Cedar-ville, 80 miles to the west. Of thislatter distance, nine miles are oiledroad; the remainder gravel-surfaced.

Virgin Valley is a stern, hard worldbeautiful, uncompromising, unyield-ing. That such a waste should haveyielded two of the largest preciousopals ever known to man, is but oneof the strange facets comprising thisstrange wild land!A U G U S T , 1 9 5 5 15

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

16/48

ON DE SERT TRAILS WITH A NATURALIST - XVIIStrange Hatcheriesfor Desert Insects

The natural world is a cooperative worldas Edmund Jaegerreveals this month when he takes a group of student companions intothe desert in quest of those little-known insect hatcheries known asplant galls.

By EDMUND C. JAEGER, D.Sc.Curator of PlantsRiverside Municipal MuseumSketches by the author 7HIS MORNING I suggested to

three of my teen-age friendsFred Hayward, Dick Dibble andJerry Becker that they accompanyme on a day's hunt for plant galls.Once started, the boys appeared tohave as much fun in this novel Nature

Fusiform oak gall Galleta grass gall

hunt as other lads would find in hunt-ing rabbits with a gun or frogs with asling-shot. An d I am sure they learnedmuch more.The galls we sought were those curi-ous insect-formed growths or defor-mities, sometimes fantastically orna-mented, which are found on certain ofour desert plants. The re are manydifferent kinds, many of them imper-fectly known, each induced to growon particular plants by different in-sects. Once attention has been directedto them they always excite much curi-osity because of their strange formsand texture.We first went out into the high des-ert where the Three-toothed Sagebrush,

Artemisia tridentata, grows. It was notlong before we had located specimensof the beautiful rose-and-green, vel-vety - surfaced, spongy - textured sage-brush gall. Some were small as hick-ory nuts, others almost the size of hens'eggs. Breaking them open the boysfound, to their amazement, in the cen-ter of the light-weight froth-like tissuea number of cells inhabited by smallyellowish or cream-colored larvae. Iexplained that these would later trans-form into pupa and then into small,delicate-winged flies known as plantmidges."But how are such galls ma de? " Iwas asked."It is not fully known," I replied,"but some scientists believe that theplant is induced to make this specialgrowth of cells because of a stimulatingsubstance injected into the leaf tissuewhen the female insect inserts her ovi-positor to lay her eggs. Oth ers thinkthat the young feeding larvae producelocal irritations which lead to the pro-duction of the supernumerary cells andstrange changes in gross plant struc-ture.Our next discovery of galls was onthe low super-spiny shrub called Cot-ton Thorn, Tetradymia spinosa. It wasnow past the season of flowering andthe plants were attractively coveredwith the soft woolly tufts of hair whichcover the numerous seeds. Here andthere on the whitened felt-coveredstems we found the fusiform woodyswellings made by the TetradymiaGallfly. With a sharp knife some ofthe galls were cut from the stem andput into our collecting box. We h opedlater the insect producers would hatchout so we could see what they lookedlike.One of the boys called attention toa strange papery gall on a rank speciesof grass. "T he cow-he rders call itGalleta Grass," I told him. "It is a

16 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

17/48

Spanish word, and I am told its trans-lation is 'hard tack' or 'salt biscuit.'Probably the name was borrowed fromsailors because this nutritious grasseven when very dry is a stand-by foodfor cattle in years of drouth."The big swelling is composed ofshort broadened leaves, induced togrow this way by a fly. Tear open thegall by pealing away the leafy scalesand inside you will probably see the fatlittle grub that made it grow. Ca ttle-men say, but I'm not at all certain thatthey are correct, that if horses or muleseat these galls it will make them verysick."It was on the nearby scrub oaks thatwe found gall hun ting really good. Ahalf dozen various forms of gall grow-ing on leaves and stems were readilycollected. It is rem arka ble that thereare more gall-making insects workingon oaks than on any other plants.Some 740 species of highly specializedgall wasps or cynipids are confined tothese trees in North America alone,each producing an abnormal growthwith its distinctive form.We found one small scrub oakbeautifully decorated with many hun-dreds of smooth, mottled, marble-sizedglobes produced on the spiny-edgedleaves by a small blackish cynipid gallinsect of ant-like appearan ce. Break-ing open the thin-walled light-weightglobose galls we found in each a centralcell or capsule where the larvae lived,effectively held in position by numerousdainty radiating fibers.On other oaks we found some ofthose large pink and rose-red fleshyswellings called "oak-ap ples." "Arethey good to eat?" one of the boysasked, and before I had time to warnhim he had bitten into one. He learnedhis folly when the bitter juice touchedhis tongu e. "L ots of tannic acid inthat one," I told him."In days past the early Americansettler made their ink by boiling a few

of such acid-filled oak-apples andthrowing a few iron nails into the tea.It yielded a black, but not too durable,writing fluid."If you will notice, some of thedried oak-apples have many tiny holesin them. These mark the places wherethe numerous small wasps which de-veloped within, eme rged. I've seen asmany as a hundred of them come forthfrom one large apple.""Was that spindly-shaped stem-swelling on that branch over there alsomade by a cynipid wasp?" one of the

boys asked."One late summer day I was lyingunder a scrub oak," I told him. "Sud-denly I found swarming about my facewhat I thought to be tiny black flies.When I looked up above me I saw

Spindle gall of cotton thorn

they were little black wasps comingfrom holes in a woody fusiform galllike the one you've just sighted."Later on in the afternoon we leftthe sagebrush-juniper country andmotored down to the low desert wherecreosote bush and burroweed were thedominant shrubs.When we directed our attention tothe finding of galls on the creosote bushwe were rewarded by locating at leastthree different kinds, two of them, asfar as I can learn, unrecorded in sci-entific literature.

The most noticeable and odd onewas found on the ends of smallbranches. It was globose and woody,covered with numerous, very small,

Encelia gall

Creosote bush gall

narrow, much modified leaves, set inclusters or radiating leaf groups. Th efresh galls were bright green but theold ones of the previous year were darkbrown to almost black in color andeasily seen. Each had been formedby a midge and had several larval cellsnear its center. The se galls are some-times mistaken by novices in desertplant lore, for creosote bush fruit.On the creosote bush we alsoglimpsed numerous smaller pea-sized

bud galls. These, while covered withmany modified leaves like the big onejust mentioned, were not woody insidebut hollow and within each was about1/10 inch long, tan to brownish larva,presumably that of a gall wasp. On oneA U G U S T , 1 9 5 5 7

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

18/48

creosote bush we counted as many as340 of these small galls. In the imme-diate area were at least a dozen bushessimilarly populated.On another bush we found a muchdifferent insect hom e. It was made oftwo leaves pasted together, reallygrown together, to form a small cap-sule, and in this we found the sametype of little tan maggot. We decidedto send this one to Dr. E. P. Felt ofStamford, Connecticut, for an identifi-

large hole in its side revealed wheresome bird or rodent had gone in toeat the fat juicy grub.Of the many gall-making organisms,plant mites, plant lice (aphids), mothsand beetles, few of them either harmor benefit the plants they work upon.In only a few cases is it known that

Sage brush velvet gall

cation. He is proba bly the best-knowngall expert in America and has writtena book describing the thousands ofAmerican Plant Galls and Gall Makers.Published by the Comstock PublishingCompany of Ithaca, New York, it givesthe student many pictures as well askeys to facilitate identification of thegalls.On the brittle bush, Encelia, wefound several small bud swellings andone very large woody stem gall, pre-sumably ma de too by a gall midge. A

they make nutrition levies upon thevigor of the plant host.Y e s , gall hunting and gall study canbe rather exciting recreation . Grea tare the latent possibilities of findingnew ones. I comm end it to wanderersover desert trails seeking novel andinteresting pastime.

The U. S. Weather Bureau has beenunable to find any evidence that atomicexplosions have had any effect on theweather beyond a few miles from theblast, nor could evidence be foundthat explosions could in the futurehave any effectgood or bad.The bureau has carried on extensiveresearch during the atomic explosionstouched off at the Nevada ProvingGrounds.Equipped with information fromthe AEC and aided by cooperativestudies carried on by Air Force andprivate scientists, the bureau has giventhe following answers to the three mostpopular theories on how the blasts areaffecting weather:1. That atomic debris serves as a

cloud seeding agent. Experiments showthat the Nevada dust has very poorproperties for serving as a cloudseeder.2 . That changes are produced inthe electrical character of the atmo-sphere. Atomic debris deposited onthe ground could change the electricalconductivity of the air near the ground,but the change would be in such a shal-low layer near the ground that it wouldbe insignificant in terms of usual atmo-spheric phenomena.

3 . That the blast's dust might inter-fere with the amount of solar radiationreaching the earth . The amo unt of dustrequired to produce any significant re-duction in worldwide incoming radia-tion and that produced by the Nevadaexplosions are separated by many or-ders of magnitude.

P i e t u t e - o f - t k - m o n t h C o n t e s t . . .Artists wh o capture the interest and beauty of the desert withcameras ca n share their art each month with Desert Magazine readersby participating in the Picture-of-the-month Contest. Open to bothamateur an d professional photographers, winning entries receive cashprizes. As long as the picture is of the desert Southwest it is eligible.Entries for the August contest must be sent to the Desert Magazineoffice. Palm Desert, California, and postmarked not later than August

1 8 . Winning prints will appe ar in the October issue. Pictures w hicharrive too late for one contest are h eld over for the next m onth. Firstprize is $10; second prize $5. For non-winning pictures accepted forpublication $3 each will be paid.HERE ARE THE RULES

1Prints for monthly contests must be black and white. 5x7 or larger, printedon glossy paper.2Each photograph submitted should be fully labeled as to subject, time andplace. Also technical data: camera, shutter speed, hour of day. etc.3PRINTS WILL BE RETURNED WHEN RETURN POSTAGE IS ENCLOSED.4All entries must be in the Desert Magazine office by the 20th of the contestmonth.5Contests are open to both amateur and professional photographers. DesertMagazine requires first publication rights only of prize winning pictures.6Time and place of photograph are immaterial, except that it must be lrom thedesert Southwest.7Judges will be selected from Desert's editorial staff, and awards will be madeimmediately after the close of the contest each month.

Address All Entries to Photo Editor'De&ent THafOfCtte PALM DESERT, CALIFORNIA

18 DESERT MAGAZINE

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

19/48

PuBy LORNA BAKERLos Angeles, California

I stepped into an ancient, crumbling pastAnd there the desert held me, held me fastGone was the world of men, the world IknewGone was the laughtertears and trouble,too ;This was a lost, a bare and fruitless landThat knew but sun and wind and rock andsandNo spot of beauty graced this barren plainThat begged no alms of God but drops ofrain;Then, as I stood upon this lonely hallOn earthI sensed a silent footstep fall,And hand on mine; where unseen fingers led,I knelt and found a buried arrowheadAnd as I held the symbol in my handThat seemed to cry, "this is not fruitlessland,But earth as He once made itundefinedWhere men have lived and toiled and weptand smiled,"I knew, somehow, my wandering soul hadfoundNot barren wasteland, but a hallowedground.

DEATH VALLEYBy DOROTHY C. CRAGENIndependence, California

I've always thought of deathAs somberNot pink or yellow, nor like mauveOr blue as indigo.Death does not have a golden floorWhere fleecy clouds cast shadowsAs they float acrossA deep blue sky.Death does not spreadA velvet blanketAnd press it down with finger tipsTo make the lights and shadowsOn the little hills.Death does not waken from their sleepThe Desert Primrose, Verbena, orThe Daisy of the Panamints.Death does not paint the sunset goldUpon the Peak of TelescopeOr adorn it with the magicOf the dawn.No, death cannot be hereBut lifeAn d all eternity.

BLUE MESABy ADA G. MCCOL L UMEl Monte, California

There's a home in the desertThat's quite dear to me,On a craggy blue mesa'Neath a Joshua tree.It's not much to look at,Some call it a shack,And though I may wanderI always come back.Its four walls are solid,They've long sheltered me,From the moods of the desert,Whatever they be.When the windows turn goldFrom the warm, setting sun,An d the mantle of nightLights the stars one by one.Comes the fragrance of sageOn the cool evening breeze.I thank you Blue MesaFor these, all of these.

Mesa Verde Pueblo Ruins. Photo by G. E. BarrettEXTREMITY

By GRACE B. WILSONKirtland, New MexicoTh e god of desert places lifts his headAbove the fields all stricken, brown and dry.No moisture darkens the arroyo bed,Nor faintest sign of cloud is in the sky.The joys of normal desert life have gone,And left behind them only heat and pain,With no relief, not even at the dawn.The desert god himself now prays for rain. a JOSHUA FORESTBy ETHEL JACOBSONFullerton, CaliforniaIn this preposterous desertlandOf alkali and sage,A dignified and proper oakOr shapely elm would be a joke,So here the trees flout impishlyTheir gracious heritageTo pop up in a fright wig andA jester's tattered cloak.

In this outrageous countrysideOf rattlesnakes and sand,The trees vie crazily, it seems,Going to grotesque extremesWith porcupines for foliage,All fractured elbows, andA murderous lampooning ofSurrealist bad dreams!

It IRetU 70it6By TANYA SOUTH

What is it that you really yearn,Innately, deep within you?That you can surely, truly earn!With purpose and with sinewBend every effort to attain,An d you will gain.Then be more honest with yourFate,More willing now to walk thestraight.A.11 that you crave, innately trueRests upon you.

TOMORROW AND TOMORROWBy R. WAYNE CHATTERTONCaldwell, Idaho

So you are movin' to the town, old friends?No need explaining Only them that spendsTheir lives out in a dead, deserted placeAmong the ghosts of them that tired ofspaceAn d sky and desert dust can know just whatIt is that takes a man where folks has gotGood heat and 'lectric light. No blame!I'll goMyself some day. But I've got fond, yeknow,And foolish, mebbe. Many times I've said,"I think I'll move to town." But in my headI thought, "Not now. Tomorrow's soonenough."And so I stayed. And snow falls on thebluff,Then winter comes, and spring, and summer,fallAnd still I stay. But now you're gone, andallThere'll be is me, alone-like, me and theseOld rotten buildin's, gettin' old! The treesAround the graves is all that's left alive.I guess I'll move to town at last. I'll thriveWhere folks is walkin' in the streets, andlightIs burnin' late at night, and all the sightsI never saw is just adown the road.But, look! I'll have to move before that loadO' snow in them there clouds falls on thebluff!Oh, well, no rush. Tomorrow's soon enough!YUCCA

By ELIZABETH NORRIS HAUERSan Jose, CaliforniaYou stand so stately in the misty moonlight,In such sweet dignity, so chastely white.Your lovely eyes cast down in meditationYou breathe a perfumed prayer into thenight.Are you the soul of some forgotten maidenWhose beauty through the ages shall notfail,A shy, young nun, who, other loves forsak-ing.Has made her vows and taken her first veil?

A U G U S T , 1955 19

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

20/48

Natives in my Garden ...Terraced gardens of Kiva, desert homestead of author, at left, who is showinggrounds to Cyria Henderson.

tec my tfaidea , ,By CHRISTENA FEAR BARNETT

7HERE WERE many obstacles inthe path of my amb ition: tolandscape my jackrabbit home-stead with native plants. Some I an-ticipated; others were whispered to mein warning; the rest I discovered as Iwent along.But the fun came in trying, and thereward I receive during every momentI spend at Kiva, my 5-acre place nearthe Joshua Tree National Monumentin California.The first step in my plan to domesti-cate native plants was to seek theexperts' advice. Percy Everett, super-intendent of the Santa Ana BotanicalGarden, kindly answered all my ques-tions and then sent me to my task withthe assurance that "native plants arenot the bad actors most people seemto think them."Extremely helpful, also, were thosesuggestions I received from the learnedand lovable octogenarian, TheodorePayne, who is now in his 51st year ofgrowing and selling natives at 2969Los Feliz Road, Los Angeles.Both Mr. Payne and Mr. Everett willadmit there are some natives amongthe things which grow on the desertthey have found very hard to domesti-cate. But there remain between 5 00or 600 native species available for do-mestic planting and I am sure that ismore than I will ever be able to ac-commodate on my five-acre nursery.From Ted Hutchison of the Grease-wood Nu rsery at Barstow 1 received

Last March, Desert Magazine asked for reports from readers whohave experimented in the domesticaiion of the desert's native plants.Among those who responded to this request was Christena F. Barnettof San Marino, California, who has converted her 5-acre jackrabbi thomestead near Joshua Tree into a lovely experimental garden in theface of tremendous od ds. In order to spen d two da ys a we ek at thehomestead she has to drive 260 miles, depend on water hauled in by atank wagon, and in some instances gouge out planting holes in the rockwith a pick. It is hard work, but the author is not looking for sy m pa thyshe's looking for more and more gardeners to share with her the thrillof enrolling as a junior partner to Nature in bringing added beauty tothe desert land.

the two most valuable of all my help-ful hints.First, Ted Hutchison told me, when-ever possible collect seed and plantsfrom approximately the same elevationat which you intend to grow them. Inspite of the fact that brittle or incensebush, Encelia farinosa, for example,growing on our homestead at the 3700foot elevation was the same species ofbrittle bush growing at near-by PalmSprings (400 foot elevation), the latterwould never do at Kiva.

Secondly, Mr. Hutchison warned meto water in such a manner that therewill be no lush growth in the fall thatcan be nipped by frost. This is done byforcing growth in the spring and thenletting the plant go into a semi-dor-mant stage by first cutting down andthen almost eliminating water by mid-summ er. This time-schedule is for thehigher desert elevations . On the lowdesert the water cut-back should startearlier so the plants can be resting byJune. My guess is that watering shouldbegin again in mid-September.

Those starting their first desert gar-dens of native plants will enjoy theexperience a great deal more if theyfirst learn to know the natives by familygroup. For those entirely without bo-tanical background a good startingpoint is Flowers of the Southwest Des-erts by Na tt N. Dodge. After that, onequickly graduates to Edmund C. Jae-ger's Desert Wild Flowers.The novice gardener will benefit byturning first to the commercial sourcesnear at hand. Before you buy anythingget acquainted with all the nurserymenwho carry natives and double-checkwith them as to what is most suitablefor your particular location.The next step in my plan was a planitself. Still not having bought anyplants, I made a rough sketch of myproperty showing the existing plantsand buildings. This sketch pointedout where 1 already had shade andwhere shade was lacking; where a dif-ference in soils existed; and generaldirection of wind.I then planted my first plantson

20 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

21/48

paper. On my sketch 1 placed themost drouth-resistant natives wherewater would be the scarcest. Theplants needing more water were placedwhere they would be sure to get it.Again, consideration of wind, sun andsoil conditions came into play to de-termine where each plant was to go.For a more pleasing effect I decidedto use perennials in groups of five ormo re. I planne d to start out with ca-mote de raton Hoffmannseggia densi-jlora, California fuchsia Zauschneriacalifornica, broad leaved Californiafuchsia Zauschneria latijolia, desertverbena Verbena goddingii, blue flaxlinum lewissi, and as many of the pent-stemon, iris and aster species as I couldfit in.Larger plants such as chuparosaBeloperone californica, brittle bush,Acton's encelia Encelia actoni, desert

mallow sphaeralcea ambigua, and theatriplex species, quail bush, salt brush,wing scale and desert holly need to beclustered at least by threes for a satis-factory display.If one has the space even the largershrubs and the flowering fruits showup better when planted in groups ratherthan as individual specimens.Annuals and bulbs need to beplante d in masse s. Mo st of the bulbswill succeed better if lightly shaded bya large shrub which does not requiremuch , if any, summer watering. The

same is true of the several blue del-phinium species and the gorgeous redlarkspur. Such plants can be purchasedfor use in three forms: seed, pottedplants or dormant roots.Having completed my layout I wasready for my buying spree. If you livein town away from your desert place,as I do, you may find that some ofyour gallon can material would bene-fit by another year's growth in a sunnyspot right in your own backyard, pro-tected from the hungry desert beasts.Growth can be encouraged with a little

steamed bone meal, an occasional ap-plication of liquid fertilizer and per-hap s a light mulch of manu re. Havethe plant rather husky before you riskit on the desert, but do not leave it inthe container long enough for it tobecome root-bound.Once you actually start planting donot skimp on care. Steamed bone meal(other preparations disintegrate tooslowly on the desert), leaf mold, wellrotted manure, liquid fertilizer, agri-cultural vitamin B and water shouldnot be spared.A proper question at this pointwould be: why take all this care withnatives when they thrive untended intheir natural habitat?The answer is simply that Naturecan afford to be prodigal. For every

plant that survives on the desert thou-sands of others fail.Proper preparation of the plantingbed is of major im portan ce. The holeneeds to be wider and deeper than theball of soil on the potted pla nts. Theminimum preparation would be toplace loose top soil in the bottom ofthe hole which was first soaked to adepth of a foot below the present limitof the roots. A watering basin for theindividual or group of plants is nextprepared.If you take your gardening seriouslymix leaf mold, a handful of steamedbone meal and a little not-too-freshmanure with the top soil previously

placed at the bottom of the hole. Soaka second time to settle the mixture soyour plant will not sink out of sightwhen you place it into the hole. Themanure should not come in direct con-tact with the root ball.Just before placing the plant intothe soil a few applications of agricul-tural vitamin B will encourage rootgrowth.I have found that many plants, bothdomestic and native, are lost becausethey were planted too deep. I set myplants at Kiva no deeper than theywere in the container. I made nume r-ous checks to make sure the plantshad not settled too deeply or sand had

The author with a Mojave Yucca one of the natives already on the home-stead when they acquired it.

A U G U S T , 1 9 5 5 21

-

8/14/2019 195508 DesertMagazine 1955 August

22/48

drifted in before I firmed the soil andfilled the water basin . The se are pre-cautions against air pockets which tendto dry out the feeding roots. A mulchwas then applied on the surface of thebasins. For this I used leaf mold andbroken twigs. After theplant is estab-lished manure can be used.If you are at all observant you willnotice that on the desert is seldomfound a young seedling of a bulb, per-ennial, shrub or tree which is not inthe protecting shade of a larger plant.The brittle bush family is about theonly exception I know of. Followingthe example of nature I gave myyoungplants some protection from heat, windand cold by sticking brush branchlingsin the water basins. A strong prevail-ing wind makes it necessary to placeeven more brush in the ground. Onthe higher desert areas this brush givesa measure of protection against frost,

t o o .Watering has much to do with thesuccess or failure of your desert garden.Shallow, frequent waterings after theplant has established itself will leavethe shrub and tree roots too close tothe surface. Less frequent but deepwatering will force the roots downwhere they can eventually shift forthemselves.I discovered as my plants grew thatwhen my annuals were blooming therewas enough lush vegetation on the restof the desert to content the rodents,rabbits and other desert vegetarians.But when the surrounding desert florawent dormant my oasis suddenly be-came the number one eating place inthe area. A fence is extremely neces-sary, I found.

I have seen a tortoise advance ona desert mallow sphaeralcea ambiguaand crunch it to the ground. Once Isaw a three foot long branch of Ari-zona cypress being towed away by agiant lizard.To divert the desert animals I builta concrete water hole for them. Anextra dividend from my expenditurehas been the fun watching the animalsand birds flock in to drink. Close bywe have added a bird feeding stationset high on a slippery pipe for theirprotection.The handicaps were formidable andI am proud of my accomplishments.The round trip from my city hometo Kiva is 260 miles. The time avail-able for my project was never morethan two days a week. All water hadto be hauled in by tank truck to fillour 800-gallon tank set on a knoll be-hind the cottage. Water pressure wasnot sufficient to do any sprinkling soI watered every stalk of green individ-ually. Last summer this jobalone tookall of my two days on the desertfrom dawn to duskplus three tank

truck loads of water each time. AtKiva the hillside was better suited forplant life than the bottom sand. Asmall shallow bedwould often containas many as 20 rocks. Digging theshrub and tree holes I ran into largestonessome so big I could only rollou t of the way.And when the stones were out Ibrought them back to place them instrategic places to prevent erosion.This partial listing of my difficulties

is not made in search of sympathy.No one forced me to my project. Itwas fun! I only mention them to pointout that even under such unfavorableconditions I met with success in do-mesticating native plants. Those withan unlimited water supply with goodpressure and who reside continuouslyon thedesert will find an immeasurablereward in beauty and satisfaction forthe time they devote to the culture oftheir garden of natives.

D e s e r t Q u i z : The days are hot on the desert this month,bu t you don't have to stay out in the sunto answer these Quiz problems. Just relaxin the coolest spot you can find, and sip a glass of ice tea or lemonadewhile youconcentrate on these puzzlers. They include geography, botany,history, mineralogy, personalities and thegeneral lore of the desert countryquestions which we hope will whet your appetite for more knowledgeof this vast and fascinating desert region. Twelve to 14 is a fair score,15 to 17 is good, 18 or over is super. Answers are on page 42.1The cactus species reputed to be a source of water for the thirsty