18 JAN 2013 #2 Hells Bells* I'm coming on like a hurricane.I'm rolling thunder, pouring

Transcript of 18 JAN 2013 #2 Hells Bells* I'm coming on like a hurricane.I'm rolling thunder, pouring

18 JAN 2013

#2 Dr. Jochen FelsenheimerTel: +49 89 589275-120

Hells Bells* >>I'm rolling thunder, pouring rain I'm coming on like a hurricane.<<

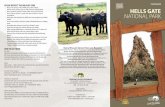

HELLS BELLS* Mario Draghi’s announcement that unlimited government bond pur-chases would be made if necessary was like an act of liberation for the markets. Now that they can look forward to low interest rates and boundless liquidity, the markets have made a marked recovery from the consequences of the euro crisis. Dwindling risk premiums on all fronts create the impression that this has solved the problem. We, on the other hand, believe that a major systemic upheaval is in the cards as a result of the artificially low interest rate levels, and that this upheaval will ultimately be the spark that ignites the next wave of crisis. As a result, this newsletter is dedicated exclusively to the question of what medium-term effects we can expect given the antic-ipated persistence of low interest rates and yields as well as on-going excess liquidity. The ECB has triggered a hurricane and there is a real risk that it will leave some degree of devastation behind as it races through the financial markets.

The spirits I summonedThe long-term consequencesof the cheap money policy

There is no doubt that the problems facing the euro zone require unu-sual answers from our politicians. You do not have to be a staunch advocate of Bundesbank policy to realise that the announcement of government bond purchases is more than merely a temporary measure in reaction to a crisis – rather, it represents a paradigm shift that is now irreversible in the short term. The ECB feels that monetary measures are an absolute must in order to stabilise the economically fragile structure of monetary union. And developments in recent months would appear to confirm that the financial markets agree. It is clear that the ECB’s measures can ultimately only act as a comple-mentary move to help soften the blow of large-scale structural re-forms. At the same time, however, they create an incentive for putting off the implementation of those necessary reforms. It is due precisely to this phenomenon that we have to expect the current interest rate level in Europe, and, as a result, the yield level on the capital markets, to persist for the foreseeable future. While this is not a foregone conclusion, the recent past has provided considerable evidence that makes such a mechanism appear likely. You do not have to look very far back in the history books to find the most prominent example, which dates back to the late 1990s in the US. Back then, Alan Greenspan was seen as the model example of an active central bank chief when he ensured (admittedly this simplifies matters slightly) that the financial system would always have enough liquidity available. Sadly, however, sufficient liquidity cannot heal structural problems – instead, it conceals them. During this period, the capital markets encountered a large number of crises which were not, in fact, exogenous shocks, but rather emerged implicitly from within the financial system itself. This phase, beginning with the oper-ation to rescue LTCM, continuing with the bursting of the technology bubble, and running right up to the sub-prime crisis, was ultimately a logically consistent development – even if a large number of other trends were at play, too. If we take the parallels between US and Eu-ropean monetary policy to their logical conclusion, it is hardly surpris-ing that Draghi is choosing to follow in Greenspan’s footsteps. It is a sure way to be praised by the markets in the short term, only for many to realise, after the event, that things are not as clear cut as they seemed after all.

2X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

Risk premiums core vs. peripherywithin the euro zone (5Y CDS)

Source: Bloomberg

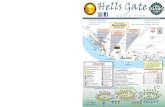

Of course, you can always ask yourself what the alternatives would have been. If the ECB had opted to pursue a more restrictive policy, the risk premiums on the European financial markets and, in particu-lar, for the peripheral countries would most likely be higher than they are today. This does not, however, justify the course of action that the ECB has chosen to follow, because after all, the financial markets are not “free” to choose which risk premium they deem to be appropriate. As a result, the current risk premiums have to be treated with caution, because they have arisen artificially (i.e. as a result of market inter-vention) and one can certainly conclude that, while every man and his dog is delighted to see falling risk premiums, they are far too low from an economic perspective. The following graphic shows the spread differences between the core euro zone and the peripheral states based on 5-year CDS levels. The spread difference has peaked at more than 600 bp and is currently sitting at around 250 bp. This means that the risk premiums between the core and the peripheral states have more than halved within the space of six months. And this is in spite of diametrically opposed fun-damental developments.

Logically, extremely low interest rates combined with sustained ex-cess liquidity translates into low real yields – namely in all market segments. The initial excitement regarding the reduction in risk pre-miums will inevitably be followed by a sense of disillusionment in the form of a lack of attractive investment opportunities. This phase is already underway. The following section thus focuses on the manifold effects of the current monetary environment.

The effects of the low interest rate policy

Severing the financial markets from the real economy

Ultimately, a central bank’s key rate is the main adjustment lever for the development of the financial markets, but also the real economy. And this is exactly where we find a central problem in the current situ-ation: the systemic upheaval within the capital markets and, in partic-ular, the banking sector means that the low interest rates and the excess liquidity are sending out signals to the capital markets – but far less so in the real economy. If liquidity is used to accompany the recapitalisation of the banking sector while the transmission mecha-nism to the real economy is damaged, this creates diverging stimuli on the financial markets and the real economy. To put it simply, the ECB’s measures are pushing yields on the capital markets down despite the lack of any development in the real economy that would justify this reduction. In order for us to see such real economic development, the low interest rate and excess liquidity would have to trigger real eco-

3X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

nomic growth impetus – in the absence of this, risks on the financial markets are consistently underestimated. Lower interest rates are supposed, in theory, to generate growth impetus that ultimately re-sults in lower risk premiums on the capital markets because, for ex-ample, the corporate default risk falls. However, this chain of effects is being completely undermined by the current monetary situation. If risk premiums are only falling because the majority of market partici-pants have to find a place for the excess liquidity in the market, this does not create any direct economic advantage for the corporate sec-tor. Except, that is, for the fact that they can borrow money on rela-tively favourable terms. This borrowing, however, does not lead to lower default rates in the long-term, but serves to push the debt level up. Precisely this phenomenon can also be applied at the sovereign level, as the developments on Europe’s periphery clearly show. In a liquidity trap, the additional provision of liquidity does not, in fact, have any impact on the real economy; rather, the effects remain con-fined to the financial markets. The announcement published by the Basel Committee in January, which stated that the global liquidity requirements in the banking sector (LCR in the course of Basel III) would be drastically toned down, has to be viewed in this very context: the mechanism of transmission from the banking sector to the real economy remains disrupted and bank lending shortages continue to pose a risk. Although we have explained in several previous newsletters how the link between the financial markets and the real economy has been severed, we feel that a brief recap is in order given the current situa-tion. The current situation is similar to that of the tech bubble, the credit bubble pre-Lehman and the situation faced by the European peripheral countries up until the end of 2009. The capital markets are factoring in a risk premium that is too low in relation to real economic developments. The growth path of capital market yields is moving further and further away from the economic reality, and the logical consequence will be a return to an economic equilibrium. This return is abrupt and relatively quick compared with the time frame over which the imbalances emerged. This adjustment process is commonly referred to as a crisis, but is nothing other than the return to a bal-anced situation. It will come as no surprise to attentive readers of this publication that the ground-breaking work of Rüdiger Dornbusch is repeatedly cited in this context. In an essay published more than 25 years ago (R. Dornbusch (1976): “Expectations and Exchange Rate Dynamics”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 84), he presented his famous “overshooting model”, which explains developments on the current markets as differences in the speed of adjustment on the capital and goods markets in the event of exogenous shocks. This idea can certainly be applied to the current situation. Although to say so will deprive the author of a job at the ECB for the rest of his life, the policy of the ECB can be described as an exogenous shock. The finan-cial market reacts far faster than the real economy and there are only two alternatives for restoring a new equilibrium: either we see a posi-tive growth shock or a drastic price adjustment on the capital markets. The first alternative calls for a certain degree of fundamental opti-mism, which we certainly share – but not in this case. The figure below shows the long-term development of US output compared with stock market performance (excluding dividends). Although phases of decou-pling can be seen, particularly in the last 15 years, a certain link can-not be denied in the long term!

4X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

It is all a matter of real economic developmentSource: Bloomberg

Portfolio theory aspectsSevering the financial markets

from the real economy

Step 1: Reduction in the risk-free interest rate Source: XAIA Investment

So what happens, purely from the perspective of allocation theory, when the central bank puts an artificially low interest rate in place? The CAPM highlights the problem. The first thing that happens is that the risk-free interest rate falls rf and the capital market line (CML) becomes steeper. The market portfolio (MP) is still on the efficient frontier, albeit with a lower risk (beta) and a lower yield. Assuming a constant utility function (NF), this effect is compensated for again because the tangent point that represents the optimum portfolio (OP) is shifted upwards and to the right on the CML.

Now, however, a second effect comes into play. Since, in a phase of low interest rates, investors are forced to make riskier investments, the efficient frontier also changes. This is because, based on the same risk, yield expectations inevitably have to fall due to the demand ef-fects if we assume, as set out above, that the increase in interest rates has no real economic effect (and, as a result, no impact on cor-porate profitability or chances of survival). The efficient frontier there-fore also moves down

5X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

Step 2: Shift in the efficient frontierSource: XAIA Investment

Step 3: Introduction of a minimum yieldSource: XAIA Investment

This is actually still a very optimistic assumption, because we believe that the negative impact on expected yields will be spread consistently over the entire investment universe. One could certainly argue that the investor demand effects mentioned above would justify a shifting of the efficient frontier to the right. Ultimately, then, all points on the efficient frontier would imply a higher risk, and lower yield expectations at the same time, compared with the respective points in the starting situation. Below, however, we would like to concentrate on the specific problem of generating a minimum yield enforced by the regulators (life insurance as an extreme example). In order to do so, we have simply added an “MR” line, which stands for a minimum return, ultimately irrespective of the risk assumed. The portfolio theory implications of a low interest rate policy now become clear as day. Investors who follow the CAPM are forced to implement a less than optimal portfolio structure. They will ultimately implement an allocation that offers too little yield compensation for the risks assumed.

At this point, we would like to explicitly point out that we deem conventional portfolio theory to be open to attack from a theoretical perspective in principle (especially when it comes to the assumption of allocation efficiency already discussed here). But it is precisely in times of crisis that its implementation yields suboptimal results. The concept of the risk-free interest rate (and all models and derivations based on the latter, e.g. performance measures) is of no informational value whatsoever in a situation in which the interest rate is the result of an anti-crisis measure (the efficiency of which we doubt) and not of real economic developments. It is fairly simple to furnish portfolio theory proof for this theory. In the following section, however, we want

6X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

to look at the effects that go beyond misallocations on the capital market and become significant from a real economic perspective.

Misallocation of capitalSevering the ties between financial markets

and the real economy

New issue volume in the EUR HY marketSource: UniCredit Research

Although the ECB’s interest rate and liquidity policy does not have much of a direct effect on the real economy, it makes an indirect im-pact via the misallocation of capital. The abovementioned portfolio effects conceal the fact that misguided real economic investment incentives are, indeed, created. If the misallocation were limited to the financial markets alone, the consequences could be seen as inherent to the system and there would be no need to fear any negative spill over effects into the economy. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Misallocation in the real economy follows the misallocation on the financial markets in a two-step process: 1. The misallocation on the capital market means that companies

rack up more debt. Even assuming that banks do not increase their lending activities despite the liquidity provided by the ECB, this is a logical consequence of the “flight to risk” triggered by the ECB’s policy. The higher demand for high yield bonds on the capital markets mean that HY companies reap particular benefits from the relatively low spread mark-ups, an effect that is further compounded by the low interest rates. For many companies, the absolute costs of borrowing on the financial markets are far lower than only a few months ago and these companies also see this as a temporary opportunity to satisfy their financing needs (and give them a little extra to play with, too). In the following chart, we have shown the new issue activity in the European HY market, which clearly highlights the Draghi effect.

2. So now, we have a scenario in which precisely those companies that shoulder large risks in real economic terms are enjoying a massive inflow of capital. Given the increase in the debt level that we have assumed, the on-going costs of borrowing have to be covered by profitable investment projects in the real economy. Companies are therefore faced with the task, against the back-drop of dwindling growth, of generating an investment return that exceeds the costs of the increased borrowing. If they fail to do so, a further increase in the debt level will be a logical consequence. Given these conditions, it is impossible to deny that there is an incentive to look for more profitable, but also riskier, pro-jects/investments. The inevitable consequence of a flight to risk on the capital markets results in exactly the same behaviour in the real economy, at least in part.

7X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

We have described the problem of the assumption of allocation effi-ciency in portfolio theory and, consequently, on the capital markets in several previous editions of the newsletter. Allocation efficiency on the financial markets describes the fact that all players seek risk-optimised yields. Our main argument explaining why this is not cur-rently the case was that it is precisely those market participants who are not utility maximisers in the sense of homo economicus who are playing more and more of a role. The most telling example was, and is, the Fed, which has now become the dominant player for US Treasuries and on the US CMBS market. The US central bank is not, in fact, hop-ing to achieve risk-optimised yields. Rather, its aim is to restore the stability of the US government bond and housing market. A central bank that maintains an artificially low interest rate level in the long term, however, not only impacts the efficient allocation of risks within the capital market, but also indirectly triggers the misal-location of capital, as a resource, in the real economy. In theory, the perfect market ensures the optimum distribution of resources using the supply and demand mechanism – and this also includes the distri-bution of capital, which can thereby provide its greatest marginal utility. Now, we will not have failed to notice that the argument behind the ECB’s intervention was precisely that it would lead to normalisa-tion on the financial markets. This argument implies that market fail-ures occurred within the financial markets which, in turn, justified state intervention. So we have the risk of market failure on the one hand, and the risk of state failure on the other. The risk premiums in the peripheral countries were not, however, a sign of state failure, but were driven by the real economic situations in these countries, mean-ing that they did not provide any justification for state intervention either. The ECB did not intervene because the markets were wrong in their risk assessment of the peripheral countries, but because its absolute top priority was to prevent the disintegration of the euro zone. Of course, it is worth asking the question as to what the viable alterna-tives could be in this sort of situation. It makes complete political sense that the ECB wants to defend its role as the last lender of re-sort. After all, without an intact euro zone, the ECB would be com-pletely surplus to requirements. Our arguments are not in any way intended to present the collapse of the euro zone as the lesser evil, because we certainly value the political objective of a united Europe and the importance of a single currency. Rather, we merely want to show what the ECB’s intervention will ultimately bring about: not only misallocation in the capital markets, but also misallocation in the real economy. This is ultimately the basis for our assessment of the cur-rent market situation. In order to dispel any remaining concerns that we might like to see the collapse of monetary union and the abolition of the fiat money system controlled by central banks, we feel the need to take a lengthy excursion into the current interpretation of the “Aus-trian School”.

Digression: German or Austrian?

The ideologisation of the Austrian School

Our attitude towards the comeback of the Austrian School and its most prominent figureheads, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich August von Hayek, can certainly be described as ambivalent. On the one hand, we, too, take pleasure in noting the elegant nature of the arguments, while on the other, we have to look at these arguments within the context of the current situation, at which point it becomes clear that some of the neoliberal ideas can now be considered outdated. First of all, it is important to remember that the hype surrounding the Austrian School follows certain cyclical patterns and that there is a certainly a strong correlation with the emergence of financial crises. Whenever speculative bubbles result from the provision of excess li-quidity by central banks, more and more voices critical of the fiat mon-ey system can be heard, using the very same arguments that were all

8X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

Theory 1: Fiat money inevitably results in financial crises, which is why it must be

replaced.

Theory 2: The euro crisis is a logical con-sequence of fiat money.

Theory 3: High sovereign debt is a symp-tom of fiat money.

the rage a century ago. It is important to bear in mind, however, that the global economy and the economic situation at that time were dominat-ed, or brought about, by dramatic geopolitical crises. For this reason alone, it is extremely difficult to draw a comparison with the current situation. At the moment, we cannot help but get the impression that a certain ideologisation of the central theories of the Austrian School is currently underway. While these ideologies are consistent with the overall theoretical structure, they appear to be far less scientifically sound. This is why we would like to dedicate the next few lines to the central theories of our dear Austrian friends, although the limited space available to us obviously means that we cannot hope to meet any real academic standards. Instead, we will merely try to categorise the ar-guments currently used by the protagonists (e.g. www.misesde.org). The fiat money made available by the central banks creates an artificial investment boom, because too much of it is made available and invest-ments (I) are no longer determined by savings (S) set aside by economic subjects. In Keynesian theory, for example, a balanced goods market is based on the equation S=I. This artificial growth created by the provi-sion of excessive liquidity logically collapses when it becomes evident that the capital gains generated cannot cover the loan liabilities in the long run. This reveals one very central point of criticism levelled against the chain of argument used by the Austrian school, which is based on the logical deductive reasoning propagated by von Mises (deriving statements on reality from logic without looking for empirical evidence). But central banks are not actually forced to make use of the options open to them for providing excess fiat money! A disciplined central bank can, of course, tie the supply of money to a real economic objec-tive. We are not ignoring the fact that central banks can have an incen-tive to abuse the right to print unlimited money, however the solution to the problem lies in a disciplined approach by central banks rather than the abolition of fiat money. There are many causes at the root of the euro crisis and its structure is obviously linked to the fiat money system. Nevertheless, monetary union certainly can work in a fiat money system. The main problem facing the euro zone is more than a much-wanted political development was enforced without considering the economic facts. Trying to balance out diverging macroeconomic developments using excess liquidity is certainly one option that can be realised using fiat money. However, the euro crisis is not the logical consequence of the fiat money system itself, but has its roots in the flawed structure of the euro zone system. More systematic use of the Target II balances for example (e.g. the need for these balances to be whittled down to zero at periodic intervals) could actually create a situation in which national central banks would not be seduced by the classic appeal of the fiat money system in the first place. In order to prevent the system from collapsing, states have an incentive to preserve fiat money, because it is ultimately not only the state, but also all of its citizens that have put their entire (economic) survival in the system’s hands (e.g. via future benefits such as pensions in units of fiat money). The state is implicitly forced to finance rescue measures and, as a result, to clock up even more debt. We strongly disagree with this argument. In earlier issues of the newsletter, we have argued sev-eral times over that the euro crisis is not a sovereign debt crisis, but rather a redistribution crisis. The sovereign debt levels of all Eurozone countries are far lower than the private financial assets (even leaving property ownership out of the equation). The state may be in debt, but the economy is not (or at least not to the same extent). The crisis measures in the euro zone have saved private assets to the detriment of state assets

9X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

Theory 4: Fiat money results in hyperinflation.

We have not reached a logical deductive conclusion, but are referring to data that can be empirically substantiated. Japan has been making excess fiat money available for more than two decades, triggering what have largely been deflationary trends during this period. In the theories set out above, we only referred to the most popular eco-nomic statements and made a conscious decision to avoid any sort of philosophical discussion, because the latter would be of little relevance as far as short-term developments on the capital markets are con-cerned. Anyone wanting to find out more should take a look at the most prominent supporters of “anarcho-liberalism”, e.g. H.-H. Hoppe. We would, however, like to take this opportunity to mention a complete-ly different argument. If we follow the ideologies of the New Austrian School, then we absolutely have to invest in real economic assets, the first of which is obviously gold. Of course, we do not want to accuse anyone, in principle, of using the theories set out above for their own good as opposed to citing them as a possible solution to the current problems. But it is difficult to avoid at least the impression that some market players are relatively lax in the way they use the arguments used by the Austrian School precisely in order to justify real economic investments. The fiat money system certainly has its advantages, too – especially in a globalised world with financial markets that are becoming more and more intertwined with each other. The solution could be to impose greater regulations on the central providers of fiat money, which would be a very pragmatic, and also very effective, solution. Even though the political will required for such a move appears to be lacking, this does not necessarily lead us to the conclusion that the current monetary system has to be abolished.

ALM: Asset liability MiracleWho is most affected by a persistent phase of

low interest rates?

In addition to the impact that the excess money supply has on capital allocation, our biggest concern lies in the systemic risks that arise for some market participants. This is where the dynamics of financial crises prove decisive: the first round effects of financial crises (i.e. the costs incurred due to the direct drop in prices in certain market segments) only account for a fraction of the overall costs. The second and third round effects, which ultimately come about because of contagion ef-fects between market segments and because of the impact on the real economy, are far more fatal. And this is where the market participants occupy the central position. The collapse of Lehman is an excellent ex-ample of this: it was only as a result of the Lehman insolvency that the subprime crisis degenerated into a global economic crisis. And the ma-jority of the total write-downs within the financial sector came after Lehman collapsed. So the question as to the impact of a prolonged period of low interest rates can only be answered if our analysis includes the potential effects on individual players in the financial markets. We have to ask ourselves which investors are being hit hardest by the current situation. And it comes as little surprise that the heaviest blow has, of course, been dealt to conventional asset-liability accounts such as Pensionskasse pension institutions and insurance companies. It lies in the very nature of these investors to try to refinance long-term liabilities using short-term financial investments when faced with a lack of long-term assets. And these very attempts prove to be an extremely tricky business in an environment characterised by capital market returns that are kept arti-ficially low. Of course, the ALM segment is just as heterogeneous as the banking sector and it is virtually impossible to argue that an insurance crisis is sparked by a systemic shock that hits all players simultaneously. But this has not been the case with the banking crisis in recent years either. It is certainly very interesting, in this context, that the regulatory author-ities deem a problem in the insurance sector to be far less relevant than a problem in the banking sector. In its most recent Global Financial Sta-

10X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

bility Report, the IMF, for example, explicitly highlighted the fact that a side-effect of the low interest rate policy pursued by the central banks (GFSR, October 2012, pp. 94 et seq.) will be long-term low interest rate margins at banks – it fails to mention the problems at other financial institutions, which appear far more dramatic. In the meantime, the ALM sector has actually become more significant in recent years, not only in its capacity as a financial intermediary, but also due to its increasingly important role as the bearer of immense capital market risks. Although the measures in 2008 to rescue AIG – at that time the largest insurance corporation in the world – attracted far less public attention than the Lehman insolvency, the insolvency of AIG would have had far more dramatic implications. It was for exactly that reason that the US state stepped in to bail out AIG but opted not to save Lehman. Insurance companies are still the main buyers of credit risks, not only on the CDS market. Particularly in recent months, there have been enormous allocation shifts towards credit risks in this sector, prompted by the low returns. While banks have to adhere to more strin-gent regulatory limits as risk-takers in many areas, ALM players are in-creasingly looking for alternative forms of lucrative risks. The current hype on the loan market or for infrastructure projects is being fuelled primarily by ALM players. On the one hand, the sector is becoming more relevant from a systemic point of view. Meanwhile, however, there is a widening gap separating the liabilities burden from the options for gen-erating corresponding returns on the capital market. The situation created by these close links and considerable interde-pendency between individual players is beginning to resemble that of the pre-Lehman days. If a small number of players from the ALM seg-ment come under pressure, this could well trigger second round effects that may ultimately be responsible for sparking a financial crisis. This is where the regulatory developments will be important. The eco-nomic need to achieve sufficient returns (i.e. returns to cover the obliga-tions that have been entered into) on the capital market implies that higher capital market risks have to be taken. This, however, is exactly what the implementation of additional regulatory restrictions (e.g. in the form of Solvency II) is designed to hinder. So while regulators are taking far-reaching measures, given the systemic relevance of the financial sector, by limiting risks, this move creates a different systemic risk at the same time – namely the default of a market participant due to an economic imperative, a default that could, in turn, prove to be conta-gious.

Market outlookToo good to be true?

The theory supported by the majority of market participants – namely that the causes of the euro crisis have not been resolved and that it is merely the symptoms of the crisis that are being eased by the ECB’s move to provide liquidity – is currently confirmed by the situation in Cy-prus. Although we do not believe that we will see another PSI scheme in the euro zone (on this topic, please refer to [in German only] “Zypern – schon wieder ein PSI?” (Cyprus – another PSI?) at www.xaia.com), the debate on possible bail-out measures between the IMF and the EU clearly shows that the fundamental problem of the close ties between the banking sector and governments will take a very long time to re-solve. With the exception of Ireland, the structural and economic problems in the countries on Europe’s periphery (particularly Spain) remain im-mense. Investors are largely aware of this too, but the policy pursued by the ECB allows them to put these concerns to the back of their minds for the time being. Ultimately, one has to admit that the ECB has bought the EU time to implement necessary reform measures. Draghi’s statement that “Later in 2013 a gradual recovery should start” at the last ECB meeting in January can certainly be interpreted as a hint that the central bank hopes to at least reduce its liquidity injections. And this shows exactly the sort of dilemma that the ECB is faced with. It must try to re-duce liquidity without knocking the financial system off balance at the

11X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

Forecast table

same time. However it has relatively little power to demand the neces-sary structural reforms within the EU. Instead, its excess liquidity actu-ally creates an incentive for delaying implementation of reforms be-cause its measures take the pressure off the markets. This means that, for the foreseeable future, the markets will be caught between two poles: the supporting technical situation (liquidity) and the sustained weak macroeconomic environment. Given the massive demand for risk at present, we believe that the first half of 2013 will still have a positive impact on the financial markets. Although this will not equate to new all-time highs on the stock mar-kets, the credit markets in particular have a realistic chance of reaping further benefits. An iTraxx Main level in the region of 90 bp (X-Over 350 bp) would appear to be within the realms of possibility. We believe, however, that these levels will be extremely expensive given the funda-mental situation (see above) and would expect them to provoke profit-taking as well (a detailed analysis can be found in the HY Outlook 2013 of Lucror Analytics at www.xaia.com). By contrast, we would not be at all surprised if the second six months of 2013 were to prove much more difficult as the liquidity effects of the ECB increasingly lose momentum. Even apart from the continuing high risk of potential shocks (from the Italian elections to a further slowdown in the Spanish property sector and then Cyprus), it will be far more diffi-cult to achieve reasonable returns this year than it was in 2012. Although anyone reading between the lines above might notice a slight mood of gloom, the quote below confirms that we can still see ourselves as convinced optimists! >>Pessimism is only ever spread by optimists. Pessimists save it for worse times.<< (Gabriel Laub)

3M 6M 9M 12M

Credit

IG Cash + o o o/-

IG CDS +/- o/- - -

HY Cash + o o/- -

HY CDS +/- o/- - -

Fin Cash o o o o

Fin CDS o o - -

Government bonds

Northern countries

o o o o

Southern countries

+/o o o/- -

iTraxx SovX WE

o o o/- -

Volatility (long) o + + ++

Euro shares o - - --

++ = “It must be love” (Madness)

+ = “Ace of Spades” (Motörhead)

o = “I Don't Care” (Ramones)

- = “This party sucks“ (The Slickee Boys)

-- = “Straight to Hell” (The Clash)

* AC/DC (1980). There is nothing more to say.

This time, special thanks go to Nadja Ferger, Benjamin Pfister, Lars Kelpien and Robert

Borrmann. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the author.

12X-ASSET NEWLETTER #2

Disclaimer This document is published for the reader’s personal information only and without any obligation, whether contrac-tual or otherwise. All information contained herein is based on carefully selected sources which are considered to be reliable. Howev-er, XAIA Investment GmbH, Munich, cannot guarantee that it is correct, complete or accurate. Any liability or warran-ty arising from this document is therefore excluded completely. The information in this document about fund products, securities and financial services has only been examined to ensure it is in harmony with Luxembourg and German law. In some legal systems, the circulation of information of this type may be subject to legal restrictions. The present information is therefore not intended for natural or legal persons whose place of residence or business headquarters is subject to a legal system which places restrictions on the circulation of information of this type. Natural or legal persons whose place of residence or business headquar-ters is subject to a foreign legal system should therefore familiarize themselves with said restrictions and comply with them as appropriate. In particular, the information contained in this document is not intended or designed for citizens of the United Kingdom or the United States of America. This document is neither a public offer nor a request to submit an offer for the acquisition of securities, fund shares or financial instruments. An investment decision regarding any securities, fund shares or financial instruments should be made on the basis of the relevant sales documents (e.g. sales brochures), but not on the basis of this document under any circum-stances. All opinions expressed in this document are based on the evaluation of XAIA Investment GmbH at the original time of their publication, regardless of when this information was received, and may change without prior notice. XAIA In-vestment GmbH therefore expressly reserves the right to change opinions expressed in this document at any time and without prior notice. XAIA Investment GmbH may have published other publications which contradict the infor-mation presented in this document or lead to other conclusions. Such publications may be based on other assump-tions, opinions and methods of analysis. The information given in this document may also be unsuitable for, or unus-able by specific investors. It is therefore provided merely by way of information and cannot replace the services of a consultant. The value of fund products, securities and financial services and the return they generate can go down as well as up. Investors may not get back the full amount invested. Past performance is not an indicator of future returns. No rep-resentation or warranty, express or implied, is provided in relation to future performance. Calculation of fund per-formance follows the so-called BVI method, simulations are based on time-weighted returns. Front-end fees and individual costs such as fees, commissions and other charges have not been included in this presentation and would have an adverse impact on returns if they were included. This document is only intended for the use of those persons at whom it is targeted. It may neither be used by other persons nor forwarded or made accessible to them in the form of publications. Nothing in this document is intended to provide or to replace tax advice and its content should not be relied upon to make investment decisions. This document is neither exhaustive nor tailored to the needs of any individual investor or specific investor groups. Investors should always consult their own tax adviser in order to understand any appli-cable tax consequences. The contents of this document are protected and may not be copied, published, taken over or used for other purpos-es in any form whatsoever without the prior written approval of XAIA Investment GmbH. © XAIA Investment GmbH 2013