155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

-

Upload

abhisek-bhadra -

Category

Documents

-

view

114 -

download

21

description

Transcript of 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

1/235

RECONSTRUCTING TONAL PRINCIPLES IN THE MUSIC OF BRAD MEHLDAU

Daniel J. Arthurs

Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree

Doctor of Philosophyin the Jacobs School of Music,

Indiana University

May 2011

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

2/235

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERSThe quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscriptand there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected againstunauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.

ProQuest LLC.789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346

UMI 3456438

Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC.

UMI Number: 3456438

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

3/235

ii

Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

Doctoral Committee

Frank Samarotto, Ph.D.

Kyle Adams

Marianne Kielian-Gilbert

Luke Gillespie

Ramon Satyendra

May 3, 2011

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

4/235

iii

2011

Daniel J. Arthurs

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

5/235

iv

Acknowledgments

I have benefited from the help of many throughout the process of completing this

work, and would like to acknowledge them individually: my committee members, Kyle

Adams, Marianne Kielian-Gilbert, Luke Gillespie, and Ramon Satyendra; Henry Martin,

who briefly but importantly shared his thoughts about jazz tonality early in my research;

and my adviser, Frank Samarotto, who played an essential part in the way I have come to

understand music in general, and who demonstrated great patience when I brought him

(often in overabundance) new ideas about the music explored here. I also would like to

thank Indiana University, the Jacobs School of Music, and the Music Theory Department,

who provided financial support through the Dissertation Year Fellowship (2009-2010),

which was vital to this works completion.

Finally, I would like to thank Brad Mehldau, whoin addition to taking time

during his busy professional schedule to correspond with megranted me permission to

reproduce selections of his music (including 29 Palms, Sehnsucht, and Unrequited),

which can be purchased from the composer at http://www.bradmehldau.com.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

6/235

v

Daniel J. Arthurs

RECONSTRUCTING TONAL PRINCIPLES IN THE MUSIC OF BRAD MEHLDAU

This study reconstructs tonal principles in selected works of New York jazz

composer and pianist Brad Mehldau through a combination of analytical approaches,

including Schenkerian analysis, which are informed by his writings and stylistic

characteristics. The contrapuntal idiosyncrasies that have come to define Mehldau as a

composer and performer suggest the applicability of Schenkerian analytical techniques.

Mehldaus expressed interests in classical norms and a linear approach motivates the

analysis of contrapuntal frameworks in terms of consonantdissonant requirements

pursued in this study. The analyses demonstrate the central role of traditional triadic

harmony in dissonance resolution, Mehldaus characteristic means of employing

melodically directed motion and, ultimately, the large-scale forms of goal-orientation that

correspond to the beginningmiddleend schemes fundamental to Schenkerian theory.

Primary works analyzed are featured in MehldausArt of the Trio, Volume 3: Songs(1998),

including Sehnsucht, Unrequited, and Convalescent, among other works and arrangements. That

rich analytical results are available through a Schenkerian perspective draws attention to

significant problems in work that seeks to apply traditional tonal analysis to other jazz

music.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

7/235

vi

Table of Contents

List of Examples ................................................................................................................ ix

List of Figures ................................................................................................................... xii

Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1

Part 1. An Introduction to Brad Mehldau and to the Study ............................................ 1

Biography and Overview of Musical Style ................................................................. 1

Writings on music ................................................................................................... 2

Mehldaus Reconstructed Tonal Principles ............................................................. 3

Jazz Chord Symbols ................................................................................................ 5

Part 2. The Problem of Jazz Analysis. .......................................................................... 10

Four Hypotheses ....................................................................................................... 12

Counter-example: Vince Guaraldis Christmastime is Here ................................. 16

Harmony and Counterpoint (Historical Context) ..................................................... 21

Defining Tonality ...................................................................................................... 22

Chapter 2: Literature Review and Methodology .............................................................. 31

Part 1. Literature Review: Theoretical Contexts of Jazz Music ................................... 31

Introduction ............................................................................................................... 31

I. Conceptual Bases of Tonal Jazz Theory (Russell, Baker, Levine) ....................... 32

II. Schenkerian Applications to Tonal Jazz (Strunk, Martin, Larson) ...................... 39

Part 2. Methodology...................................................................................................... 55

Reconciling Chord Symbols and Voice-Leading ..................................................... 55

Schenkerian Analysis ................................................................................................ 56

Plasticity Analysis ..................................................................................................... 57

Transcription ............................................................................................................. 57

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

8/235

vii

Chapter 3: Sehnsuchtand the Suspension ......................................................................... 60

Part 1. The Suspension and the BeginningMiddleEnd Paradigm ............................. 60

Suspensions in Jazz Music ........................................................................................ 65

Part 2. Analysis of Sehnsucht........................................................................................ 72

Foreground and Middleground ................................................................................. 79

Deep Middleground/Background.............................................................................. 93

Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 94

Chapter 4: Temporal Plasticity and Solo Voice Leading in Unrequited.......................... 96

Part 1. Temporal Plasticity ............................................................................................ 96

Part 2. Temporal Planes .............................................................................................. 102

Part 3. Analysis of Improvisation. .............................................................................. 110

Introduction ............................................................................................................. 110

From Thematic Voice Leading to Solo Voice Leading .......................................... 112

Larry Grenadiers Bass Solo ................................................................................... 117

Foreground .......................................................................................................... 117

Mehldaus Solo ....................................................................................................... 121

Skewing Tonal Durations: micro-analysis of chorus 1, mm. 6-8 ....................... 122

Chorus 1 .................................................................................................................. 124

mm. 116 ............................................................................................................ 127

mm. 1732 .......................................................................................................... 129

Chorus 2 .................................................................................................................. 131

Chorus 3 .................................................................................................................. 135

Special note regarding temporal planes and the climax ...................................... 141

Part 4. Aspects of Closure ........................................................................................... 143

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

9/235

viii

Summary ..................................................................................................................... 148

Chapter 5: Aspects of the Free Fantasy in Convalescent................................................ 149

Part 1. Aspects of the Free Fantasy ............................................................................. 153

I. The Pedal Point .................................................................................................... 153

II. The Free Fantasy Transformed .......................................................................... 164

Part 2. Analysis of Convalescent................................................................................ 173

Formal Analysis ...................................................................................................... 173

Voice-Leading analysis: Preliminaries ................................................................... 175

CDambiguity .................................................................................................. 177

Voice transfer ...................................................................................................... 177

MajorMinor ambiguity (Bversus B)............................................................... 178

Piano solo, chorus 1 (0:53 1:56) ...................................................................... 179

Piano solo, chorus 2 (1:56 3:20) ...................................................................... 187

Bass solo ............................................................................................................. 201

Return of the theme ................................................................................................. 202

The Coda ................................................................................................................. 202

Considerations regarding large-scale structure ....................................................... 203

Summary ..................................................................................................................... 205

Chapter 6: Conclusions ................................................................................................... 206

The Anxiety of Influence in Jazz ................................................................................ 206

The Nature of a Style .............................................................................................. 210

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................213

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

10/235

ix

Examples

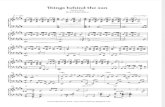

1.1 29 Palms, score, mm. 116 ......................................................................................7

1.2 29 Palms, harmonic analysis of mm. 1516 ............................................................7

1.3 Christmastime Is Here (Vince Guarldi, 1965), A section, voice-leading

analysis .......................................................................................................18

1.4 29 Palms, mm. 128 (A and B sections), with form annotations ..........................27

1.5 29 Palms, mm. 14, harmonic realization and analysis .........................................27

1.6 29 Palms, mm. 34, hypothetical phrase ending in C minor .................................29

1.7 29 Palms, mm. 1316, voice-leading analysis .......................................................30

2.1 Aldwell and Schachters example 27-18 ...............................................................47

2.2 Larsons example 2.4, A Chain of Ninths and Thirteenths ...........................50

2.3 A 913 LIP rendered into a two-part keyboard figuration ....................................51

2.4 A chain of 98 Suspensions in Sehnsucht, mm. 2528 .........................................56

3.1 Sehnsucht, score, with annotations ........................................................................63

3.2 Three voice-leading interpretations of Bsusadd3

in Sehnsucht,m. 17 .....................67

3.3 For All We Know, chorus (Coots and Lewis, 1934) ..........................................70

3.4 For All We Know, transcription of Mehldaus right hand, with bass ................70

3.5 Chopin, mazurka, op. 17, no. 4, mm. 114 ............................................................73

3.6 Schumann, Aus meinen Thrnen,Dichterliebe, Op. 48, no. 2, opening ............76

3.7 Sehnsucht,mm. 15, transcription and voice-leading analysis .............................78

3.8 Sehnsucht, foreground and middleground voice-leading (mm. 1-22) ...................81

3.9 Chain of 98 Suspensions in Sehnsucht, mm. 2528 ............................................87

3.10 BACH motives in Sehnsucht, mm. 2935 .......................................................93

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

11/235

x

3.11 Sehnsucht, deep middleground and background ....................................................94

4.1 Unrequited, score ...................................................................................................97

4.2 Skewed harmonic durations in Unrequited,mm. 14 .........................................100

4.3 Unrequited, theme, complete voice-leading analysis ..........................................101

4.4 Unrequited, piano transcription, fromArt of the Trio, Volume 3: Songs,0:001:25 .................................................................................................103

4.5 Unrequited, three-voice species model and temporal planes (whole note =one measure) ............................................................................................107

4.6 Analogous tonal plans in Unrequited, mm. 116 and 1621 ..............................109

4.7 Solo voice-leading choices compared to thematic voice-leading (mm. 1632) ..115

4.8 Larry Grenadiers bass solo in Unrequited, with voice-leading analysis ............119

4.9 Mehldaus solo, chorus 1, mm. 116 ...................................................................125

4.10 Unrequited, piano solo, chorus 1, with voice-leading analysis ...........................126

4.11 Bifurcation of harmony in chorus 1, mm. 816 ...................................................127

4.12 Unrequited, piano solo, chorus 2, with voice-leading analysis ...........................132

4.13 Unrequited, chorus 2, middleground ...................................................................134

4.14 Unrequited, piano solo, chorus 3, with voice-leading analysis ...........................137

4.15 Unrequited, score, coda (mm. 3339) .................................................................144

4.16 Unrequited, coda, with voice-leading analysis ....................................................146

4.17 Two scenarios for concluding with a picardy third .............................................147

5.1 A transcription of Convalescent, theme (with annotations).................................151

5.2 Convalescent, theme, complete voice-leading analysis .......................................152

5.3 Convalescent, opening melodys two-part counterpoint (mm. 17)....................153

5.4 C. P. E. Bachs figure 402....................................................................................153

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

12/235

xi

5.5 Tonal cycling in Convalescentand in an illustration by C. P. E. Bach ...............155

5.6 Naima(John Coltrane, 1959), harmonic reduction ..............................................158

5.7 Green Dolphin Street(Bronislau Kaper and Ned Washington, 1947), A

section, harmonic reduction .....................................................................159

5.8 Green Dolphin Street, with classical realization of harmony over tonic pedal ...160

5.9 Black Narcissus(Joe Henderson, 1975) ..............................................................161

5.10 Conclusions of chorus 1 and chorus 2 .................................................................165

5.11 C. P. E. Bachs figure 477, Broken chords must not progress too rapidly or

unevenly .................................................................................................167

5.12 Convalescent, coda ..............................................................................................171

5.13 Harmonic processes within the coda ....................................................................172

5.14 Convalescent, piano solo, chorus 1, with voice-leading analysis ........................180

5.15 Convalescent, piano solo, chorus 1, middleground .............................................182

5.16 Convalescent, piano solo, chorus 2, with voice-leading analysis ........................188

5.17 Convalescent, piano solo, chorus 2, middleground and background ...................190

5.18 Chorus 2, opening melodic figure (1:59) .............................................................191

5.19 Voice-leading stages in chorus 2, 2:042:08 .......................................................192

5.20 Interplay between Mehldau and Grenadier, 2:142:25 ........................................195

5.21 Chorus 2, 2:302:59, voice-leading .....................................................................198

5.22 Three similar passages in the piano solo of Convalescent...................................200

5.23 Register transfer/transcendence in Convalescent.................................................204

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

13/235

xii

Figures

1.1 Henry Martins tonal cues in twentieth century music ..........................................23

1.2 Martins criteria for tonality as typified by modern jazz .......................................24

1.3 Martins criteria for tonality notfollowed by modern jazz ....................................25

2.1 David Bakers illustration of the bebop scale (with annotations) ..........................34

2.2 Bakers non-contextual substitution of a major chord ...........................................36

2.3 Bakers non-contextual substitution of a Dmi7 chord ...........................................37

2.4 Bakers non-contextual substitution of a G7chord ................................................38

2.5 Bakers example 3, a chart illustrating a matrix which [Baker] evolved anddeveloped based on the Coltrane changes ................................................38

2.6 Henry Martins examples 2-5 and 2-6 (opening measures to a Bach partita) .......40

2.7 Martins examples 2-7 and 2-8 (Charlie Parkers solo from Shaw Nuff).............41

4.1 Interrupted voice-leading structure in Unrequited...............................................136

5.1 Summary of solo durations in Convalescent.......................................................165

5.2 Three temporal planes in Convalescent...............................................................169

5.3 Synopsis of rounded binary form of Convalescent,theme ..................................174

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

14/235

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

Part 1. An Introduction to Brad Mehldau and to the Study

Biography and Overview of Musical Style

Brad Mehldau (b. 1970), like many jazz pianists, was first trained in the classical

tradition. Apparently discovering jazz only by his teens, he quickly received local

attention in his home of West Hartford, Connecticut. After graduating from high school,

he moved to New York and attended the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music

while playing and recording as a sideman. At the New School Mehldau studied with

Fred Hersch, Junior Mance and Kenny Werner. He also was enrolled in music courses

that taught musicianship skills and history (which included a core music class with jazz

theory scholar, Henry Martin).1 Leaving the New School in 1993, Mehldau gained

notoriety as a sideman, but quickly developed into a leader. His trio, featuring Larry

Grenadier on bass and Jorge Rossy on drums, began touring worldwide by the late 1990s.

Five of Mehldaus earlier albums with Grenadier and Rossy were grouped by him

under the collection title,Art of the Trio.2 This study will focus primarily on Mehldaus

1998 album,Art of the Trio, Volume 3: Songs. The albums track listing typifies the

diversity of music in his albums, featuring several of his own compositions, a couple of

arrangements of standard jazz repertory, an adaptation of a song by contemporary rock

group Radiohead (Exit Music [for a Film]), and an adaptation of a 1968 song by the

late British singer/songwriter Nick Drake (River Man).3

1. From a discussion with Henry Martin (personal communication).

2. For a select discography, see the bibliography.

3. For a complete track listing, see the bibliography.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

15/235

2

In 2005 he began collaborating with Jeff Ballard on drums, replacing Rossy, and

from 2006-2008 he collaborated with world-renowned jazz guitarist Pat Metheny.

Today, Mehldaus trio continues to tour worldwide.

Critics, from early in his career, have noted the fusion of classical and jazz

elements in his music.4 Further, many have identified an idiosyncrasy within his style

(which, I will later argue, is due in large part to a linear approach to harmony). This

idiosyncrasy includes the use of imitation and dialogue between left and right hands in

both his compositions and improvisations.5

Writings on music

Mehldau is outspoken on his opinions in support of an autonomous artwork. He

strives to blend the extemporaneous with the preconceived. His official biography states,

[Mehldau] has a deep fascination for the formal architecture of music, and it

informs everything he plays. In his most inspired playing, the actual structure ofhis musical thought serves as an expressive device. As he plays, he is listening to

how the ideas unwind, and the order in which they reveal themselves. Each tune

has a strongly felt narrative arch, whether it expresses itself in a beginning and anend, or something left intentionally open-ended.6

Though written in the third person, these words are likely penned by Mehldau.

The erudition expressed in this quote is typical of his numerous other writings (many of

which are catalogued in the first section of the bibliography). Through his writings

4. See, for instance, Adam Shatz, A Jazz Pianist with a Brahmsian Bent, Arts and Leisure,NewYork Times, July 27, 1999, section 2, p. 31.

5. For a recent stylistic assessment of Mehldaus style, see Ted Gioia, Assessing Mehldau at

Mid-Career, entry posted December 31, 2007, http://www.jazz.com/features-and-interviews/2007/12/31/assessing-brad-mehldau-at-mid-career (accessed 28 January 2009).

6. From his website, http://www.bradmehldau.com, accessed April 14, 2008.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

16/235

3

Mehldau claims his music has strong European influences. The classical influence in his

style of jazz he describes as located in the compositional process:

That came about as a result of studying a lot of the contrapuntal aspects ofclassical music. I tried to get away from a one-note melody and a chord under it,

and tried to explore the relationships between several notes moving

independently. The idea of generating a whole composition from a smallamount of thematic material is very alluring to me, and resulted from studying the

compositions of great classical composers like Beethoven and Brahms.7

Mehldaus Reconstructed Tonal Principles

Essential to this study is an underlying hypothesis: that the triad plays a central

role in dissonance resolution. The analyses will demonstrate the existence of a clear

contrapuntal relationship establishing specific consonancedissonance conditions,

ultimately promoting motion and goal-directedness, all in a traditional sense.8 I examine

selected tonal works from Mehldaus output that illustrate in novel ways how tonal

motion can promote a unified whole. The means by which he deploys these principles

will serve as evidence that a traditional tonal approach to music can thrive in a post-tonal

era. That the triad serves as contrapuntal basis for Mehldaus music situates these pieces

within a reconstructed tonal space as defined by Schenker in his theories of tonality.

The following techniques are among the most important that will be examined in

this study: (1) use of suspensions with keyboard figuration typical of the tonal era (e.g.,

mordents or trills); (2) linear intervallic patterns of a tonal nature (i.e., 105, 710, etc.,

exclusive of extended tertian patterns9); (3) 76 chains and 56 exchanges; (4) chromatic

7. The Brad Mehldau Collection(Milwaukee: Hal Leonard, ca. 2002). More excerpts of

Mehldaus writing can be found in part 2 of this chapter.

8. I explore various criteria towards a more specific idea of what is meant by in a traditionalsense in part 2, Defining Tonality.

9. See chapter 2, Linear Intervallic Patterns, p. 48ff.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

17/235

4

third progressions, requiring enharmonic reinterpretation; (5) melodic turn figures and

other idioms suggestive of the tonal era; (6) tonal puns on important melodic pitches; and

(7) functional tonal cycling.10

This study works out intuitions I had about Mehldaus music long before I

encountered his writings. As I became familiar with his music, it became apparent that

classical and jazz elements were being combined: my classical knowledge more

frequently informed my understanding of his jazz music, rather than my jazz knowledge

informing my understanding of his traditional tonality. From a young age, jazz style

has been my second language with classical styles as my first. The cultural reasons for

this are many, and makes for a project not to be explored here. But I believe it is

important for American musicians and scholars to understand whythe inequality between

classical and jazz languages exists in the hopes of understanding how one musical

language can inform the other. For example, many pianists who specialize in jazz first

train classically.

11

While the ability to improvise competently in the jazz style sets apart

spectator and specialist, all musicians who attend the university are required to go

through a music-theory curriculum that stresses one language over the other.

Students reconstruct tonal principles all the time, particularly when the task is to

compose model compositions in a certain style. They are evaluated on how well they

10. In many ways this study departs from Joseph N. Strauss definition of prolongation in tonalmusic; see Joseph N. Straus, The Problem of Prolongation in Post-Tonal Music,Journal of Music Theory

31, no. 1 (1987): 1-21.

11. Among the most prominent jazz pianists who first trained classically are Herbie Hancock,

Dave Brubeck, Armen Donelian, John Medeski, AndrPrevin, Cyrus Chestnut, Bill Cunliffe, and Hal

Galper. All these can be confirmed in brief biographical sketches found at www.oxfordmusiconline.com(accessed January 28, 2009). It should be noted that many non-pianists also first trained classically (Benny

Goodman being one of the most famous examples), but I would hypothesize that a higher percentage of

jazzpianistsfirst studied classical music.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

18/235

5

employ tonal principles. Melodic turns of phrases help accomplish their task, but without

a proper knowledge of certain harmonic principles, model compositions can stray from

the desired style. Even when the style is achieved, model compositions are generally not

intended to pass as masterpieces, but serve as demonstrations of earlier styles and genres.

Model compositions recreate the wheel, as it were, but are not normally intended to

achieve the status of a unique work of special inspiration.

In a post-modern world, where collages of musical styles are the norm, Mehldau

has singled out the use of tonal principles not unlike those learned in model

compositions, perhaps invigorated by a jazz setting. By integrating tonal principles with

the jazz tradition, his compositions surpass the status of model composition. Indeed,

these tonal principles in part define his voice as a composer and improviser,

distinguishing him from other jazz pianists of the last fifty years. Reconstructing tonal

principles in Mehldaus music, then, shows us how his art transcends the model

composition, and, indeed, how these principles become a springboard to compositional

innovation.

Jazz Chord Symbols

Jazz chord symbols do not reveal long-term relationships. Interrelationships from

chord to chord frequently instantiate the IIVI formula. This formula often has short-

term implications for prolonging the third chord, as can be demonstrated at the

foreground level in a Schenkerian analytical context. Nevertheless, root motion through

the circle of fifths is the underlying principle for such a formula. Beyond the circle of

fifths, jazz chord symbols frequently do little to demonstrate specific functional

connections from chord to chord. The information provided by each jazz chord symbol

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

19/235

6

alone cannot illustrate the perceived motion, or voice-leading, from chord to chord. In

this study I demonstrate how linear analysis can meaningfully reveal what happens in

motion betweenchords, superseding the information provided by chord symbols on a

score.

To be sure, the decision to stress melodic over harmonic approaches has been a

recurring point of contention throughout the history of music theory. I do not wish to

downplay the importance of jazz harmony (or even classical harmony) so much as I wish

to elevate an awareness of contrapuntal situations that are not normally apparent in jazz

music. While Mehldaus music at times is strikingly different from traditional jazz, his

own practice of accompanying his published themes with chord symbols is a traditional

jazz practice: the symbols name vertical arrangements of a given collection of melodic

and harmonic material at specific points within the music, usually one to two chords per

measure. Given the contrapuntal approach to many of Mehldaus compositions, though,

chord symbols cannot tell us the linear story that animates the rich surface of the music.

In example 1.1, the final three chords to Mehldaus 29 Palmsis shown in mm.

1516.12

The tonic is approached by a second inversion dominant seventh in the key of B

major, which is notated on the score as G 7/D. This symbol is intended to illustrate an

inversion of a G flat dominant seventh, with D flat in the bass. In B major, it functions in

tonal theory as a passing V$harmony, or an F sharp dominant seventh (enharmonically

reinterpreted from G flat). Three of the four voices are suspended over the tonic with a

chromatic neighbor note, G natural, added to the texture. This is indicated on the score as

12. 29 Palmsis an ABA form, so this progression, illustrated only midway through the score,

effectively concludes the piece. 29 Palmsis performed in Brad Mehldau,Places, Warner Bros. 9 47693-2

(CD), 2000; the chord symbols are Mehldaus.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

20/235

c

i

r

2

p

xample 1.1.

xample 1.2.

/B. Note t

ord sugges

illustrated

solve on th

13. I

Palms, Sehn

rposes, and a

29 Palms, s

29 Palms,

at Fis pro

s a tonic ar

n figured b

second hal

ould like to th

ucht(exampl

e not intended

?

core, mm. 1

armonic a

ided by the

ival on B w

ss notation

f of m. 16 t

nk Brad Meh

3.1), and Un

for performa

?

4

4

B:

7

1613

alysis of m

melody yet

ith both sus

in example

the tonic tr

dau for granti

equited(exam

ce.

4

4

G b/Db

V$

. 1516

is absent in

ensions an

1.2. These

iad, which i

g me permiss

ple 4.1). The

w..

.

.

w

G/B

I~~~~~~~%n

the chord s

an upper n

issonances

s indicated

ion to reprodu

e are intended

B

~

mbol. Thi

eighbor, wh

appropriate

n the score

ce his lead she

for analytical

ich

y

as

et to

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

21/235

8

B.14 As an analytical listener of both jazz and classical music, I do not experience the

three chords as they are indicated on the score of example 1.1. The chord symbol

notation indicated by Mehldau differs from how I hear the final three chords as a unit. I

instead attend to the motionbetween each chord that signals an approach, suspension, and

repose that constitutes a cadence, illustrated in example 1.2. The traditional tonal

processes that describe a suspension instead aptly illustrate my experience of the final

bars: (1) a dominant harmony serves as consonantpreparationfor (2) thesuspensionof

dominant harmony over the tonic arrival, with the additional dissonance of a neighbor-

note, G,15

followed by (3) resolutionto the tonic triad.

Mehldaus creative use of G/B to explain the double suspension that takes place

in the penultimate measure to 29 Palmsis a clear example of a reconstructed tonal

principle that one would be hard pressed to identify in a typical tonal jazz piece. For

instance, by incorporating the melody one can label the harmony with complex chord

symbols as G-75/B or G7

95/B. Both symbols accurately account for the harmonic

content of the penultimate chord. Instead, Mehldau does away with a major or minor

distinction and invokes threesyntactical musical elements to render the identity of the

double suspension: the chord symbol of a diminished triad (G), the bass-pedal symbol

(/B), and the melody (F4). In addition, by using the diminished symbol, Mehldau is

perhaps sensitive to the state of suspension by not choosing a symbol that identifies a

14. Here the triangle seems to be indicating a major triad, without the customary major seventh (asinformed by the performance).

15. The G itself can function as the flat-nine of a dominant, or seventh of a leading-tonediminished seventh chord, both of which represents prolongation of the dominant. In this case, the G is not

prepared as a suspension, hence its neighbor-note designation. In tonal analysis, the penultimate harmony

is heard as a vii7/V over a tonic pedal.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

22/235

9

major or minor connotation over a non-tonic harmony, as in the two alternatives I

provided above. In both cases, G is not the root harmonywhether major, minor, or

diminishedsince B major is the ultimate goal.

This complex coordination of symbols and music realizes a somewhat

straightforward voice-leading situation. That there is no better way to demonstrate this

simple voice-leading situation to a jazz musician (on the score) underscores the friction

that motivates this study. More importantly, this study raises questions about the

assumptions of tonal jazz as it relates to linear analysis, particularly in a Schenkerian

orientation.

While jazz music often emphasizes parsimonious voice-leading, the motions just

described between harmonies are not a given stylistic requisite in jazz music, not even in

the tonal jazz repertory. In 29 Palmstones are activated as a source of harmonic tension

in a specific way. These contrapuntal tensions are driven by a goal-orientation towards a

tonic triad. Triadic goal-orientation is not a requisite, nor is it preferred, for much tonal

jazz music.16

The above example demonstrated specific functions for each scale degree,

namely, the neighbor note and the suspensions. Neither of these functions are made

evident by the chord symbols. To be sure, this study is not a critique of jazz practice,

such as chord-symbol notation in Mehldaus music or in jazz in general. Rather, this

study points to the friction evident between two languages and how one jazz composer

appropriates his musical style from the nineteenth-century German Romantic tradition (as

16. Jazz musicians are taught from an early stage that it is outside the style to emphasize anything

as basic as a triad; students are encourage to substitute triads with acceptable extended tertian hamonies.

Consider this statement from Walter Piston, who wrote, Students of jazz techniques will recognize that anentire harmonic vocabulary based on the complete set of added-sixth chord and non-dominant sevenths and

ninths exists in that art, indeed defining the normative chordal states in a harmony where pure triads are

rare. Walter Piston,Harmony, 5th ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987), 483.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

23/235

10

evinced in his writings) in order to create a renewed sense of tonality in this post-modern

age.

Part 2. The Problem of Jazz Analysis.

In traditional analysis of jazz music, scholars have debated over the influences of

the Western European tradition. The main argument is that jazz, deriving primarily from

West African music culture, is incompatible with Western European analytical

techniques. That is, the analyses that aim to understand the constituent parts of a jazz

work should notresemble those applied to Western European music.

More recently, an African-American literary theory by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. has

been applied to music of West African origin: Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. has applied Gatess

term, signifying, to the performer in jazz music.17

Signifying essentially involves the

art of misdirection. When applied to literary theory, it is a play on word meaning; when

applied to music, it becomes sonically oriented as an act involving the performers play

on musical meaning as directed towards the listener. The performer need not concern

himself with communicating to the audience. The performer, in fact, strives to signify on

the audience in such a way as to exert a kind of artistic domination. For example, Miles

Davis was known to turn his back on the audience in many of his live performances, as if

not only to ignore but to refuse to acknowledge his audiences presence. This

antagonistic approach to the performance of jazz has been historically situated within

17. See Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The Signifyin Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary

Criticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), and its application to music in Samuel A. Floyd, Jr.,

The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1995).

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

24/235

11

certain reactionary impulses brought on by social and cultural contexts, particularly with

regard to racial equality and civil rights.18

Without reference to cultural issues, Alex Lubet has argued from a pragmatic

position that jazz music is process-oriented, based on the traditional West African

practices of performing to certain environmental cadences, whereas Western European

music is governed by philosophical principles of teleology; its analytical application to

jazz music therefore is fundamentally incompatible.19

The reasoning lies again in the

argument that jazz music owes its development to West African musical tradition, not

Western European tradition, and therefore the notion of goal orientation as an analytical

premise is misplaced in jazz analysis.

While there is some truth to this argument, the problem is in attributing the term

jazz to such a wide variety of music. Lubets argument, for instance, ought not to be

applied to Mehldaus music. Yet Mehldaus music is considered jazz, which falls under

Lubets broad umbrella. Based on his criteria, Lubet might not even consider Mehldaus

music jazz, given Mehldaus clear admission of Western European influence. While the

typical apparatus for jazz analysis has been questioned, one will still find Western

musical analytical techniques applied to jazz music from Schenkerian analysis in tonal

jazz to set theory in free jazz. The application of tonal forms of analysis to jazz music

has required some modification, however. Indeed, the fact that one cannot find

18. See Floyd, Jr.,Power of Black Music, Gates, Jr., Signifyin Monkey, as well as Robert Walser,

Out of Notes: Signification, Interpretation, and the Problem of Miles Davis, The Musical Quarterly77,

no. 2 (1993): 343-365. The application of Gatess theory of signifying has been applied to rap music as

well; see Richard Littlefield,Frames and Framing: The Margins of Music Analysis(Matra: InternationalSemiotics Institute, Semiotic Society of Finland, 2001).

19. Alex Lubet, Body and Soul,Annual Review of Jazz Studies7 (1994-95):163-80.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

25/235

12

unmodified applications of tonal analysis would support those who would contend for a

distinction between Western European and West African music.

Four Hypotheses

In response to the above contentious positions, I propose four hypotheses to

situate Mehldaus music within the ongoing debate between jazz and Western European

classical music. The music explored in this study operates within a reconstructed tonal

space, which is often accompanied by the following activities:

1. reviving the traditional tonal language (reconstructed at the end of the 20th century).

2. recreating the self-contained work with a beginningmiddleend paradigm.

3. erasing jazzs distinction between the composed and improvised material.

4. reasserting the autonomy of the artwork independent of source material

(arrangements of jazz standards, rock music, etc.), thereby removing the music from a

context with which it was inextricably linked.

To demonstrate these hypotheses, I will apply Schenkerian analytical methods to

Mehldaus music. Operating from within a reconstructed tonal space, essentially there is

no analytical modification to the methodology, since the music is free from struggle with

the past, in the sense of Joseph Strauss application of Harold Blooms anxiety of

influence.20

By removing such historicized, contextual parameters, I will show that the

music is readily engaged by traditional methods of analysis.

Writers have already identified similarities of Mehldaus music with a wide range

of classical composers (J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms

20. See Joseph N. Straus, The Anxiety of Influence in Twentieth-Century Music, The Journalof Musicology9, no. 4 (Fall 1991): 430-47 andRemaking the Past: Musical Modernism and the Influence

of the Tonal Tradition(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990).

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

26/235

13

to name those cited by Mehldau and his critics), and particular musical elements in his

compositions have warranted these comparisons. When a piece features surface

counterpoint, for instance, some have referred to it as having similarities to Bach; when

the piece is dramatic, Beethovens persona is conjured; when his music exploits motivic

development, Brahmss name is evoked; etc. Rather than identifying his music by these

musical stereotypes and proposing that Mehldau is recreating the music of each of these

composers, I suggest that the numerous musical traits these composers share constitutes

the reconstructed tonal space of Mehldaus music.

In a recent communication with the composer, Mehldau states,

One of my pet peeves is that tonality itselfyou could also say functional

harmonyis bypassed in much writing about new music in general, perhaps

because it requires some more specialized knowledge. The unfortunate result isthat people are missing where the action is[engaging in] a tonal language.

21

Mehldau adopts a Romantic aesthetic in his music, which explicitly removes it

fromsocio-politicalcontexts (to which jazz has traditionally been intimately linked).

The apparently unbiased nature of the work allows for multiplicity of meanings, a

plurality which Mehldau himself has made known:

My interpretations are interchangeable and contingent.

There is no need for an analogue to this music, one could argue, whether itinvolves sex, death, flowers or airplanes. To the extent that music is about

anything, it generates its story from within, and spins a wordless narrative that

simply tells us of its own presence and the distance it keeps from us.

This Kantian idea of the autonomous artwork is particularly appealing formusic because it gives its nonlinguistic aspect a privileged status. The dualistic

rub of speech communication takes place between a word that signifies and a

concept that is signified. Between those poles are cognitive badlands. Somethingis always lost or mutilated in the journey from thought to utterance, but music

would seem to provide a more direct perceptual experience for the listener.

21. Brad Mehldau, e-mail message to author, August 18, 2009.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

27/235

14

Because it doesnt clearly signify anything outside of itself, when we listen to itwe engage in a kind of pure consciousness, unfettered by any referent concept.

22

Mehldaus music demonstrates a clear triadicmelodic and harmonic relationship.

The interacting contrapuntal lines can be more than the source of harmonic tension: they

can serve as a motivic basis for the subsequent improvisation and interplay in the trio.

This interplay ultimately culminates in a final musical product of novel artistic creation.

I would hypothesize that Mehldaus music conveys a cohesiveness that sounds as if he

were creating a unified whole from beginning to end extemporaneously. To further

impress upon the listener the complexity of such an illusion, it will be argued that the

traditional interplay of the trio (i.e., the ability to communicate musicallyon the spot

whereby rhythmic, harmonic, and/or melodic elements are in alignment) conveys a

collectively improvised, fully-unified work (see in particular the analysis of Unrequitedin

chapter 4).

Interpreting Blooms anxiety of influence, Straus asserts that composers know

that the lost Eden of the tonal common practice can never be regained in its original

fullness. In this postlapsarian world, composition becomes a struggle for priority, a

struggle to avoid being overwhelmed by a tradition that seems to gain in strength as it

ages.23

On the contrary, Mehldaus music does not exhibit a struggle with the past, but

more or less embraces it as if by willful suspension of disbelief. The lack of self-

conscious anachronism in Mehldaus music makes it particularly apt for the current

study, since it readily allows one to enter into a tonal environment.

22. Brad Mehldau, Brahms, Interpretation, and Improvisation,Jazz Times(February 2001),reprinted on Mehldaus website http://www.bradmehldau.com/writing, accessed 22 February 2008.

23. Straus, Anxiety of Influence, 447.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

28/235

15

This study will investigate in Mehldaus music fundamental concepts of tonality

that are currently taken for granted by jazz musicians: the passing tone, neighbor note,

and suspension, among others. A passing tone is active in a prolongational context in

which it becomes articulated as a dissonance that bridges two consonances; jazz generally

has no requirement for specific consonancedissonance conditions within harmonic

progressions. The suspension is perhaps the most complex of foreground phenomena

that, in its very nature, suggests melodic motion among chords.

Harmonically, jazz music embodies Schoenbergs notion of the emancipation of

dissonance. Jazz theorists regard the dominant thirteen an independent entity. A sus

chord is not considered to require a resolution (see chapter 3 for more on sus chords).

Jazz harmony, in all its complexity, represents the reification of linear phenomena, frozen

into a vertical form. Though received jazz methodologies teach smooth voice-leading

when incorporating successions of complex harmonies, the focus is upon the law of the

shortest way: parsimony and close proximity of pitch materials from one chord to the

next. Parallel motion of consonant fifths and dissonant sevenths are permitted in jazz

methods. As I will demonstrate in the literature review, below, the use of the term voice-

leadingis fundamentally different from the kind of voice-leading that lies at the

foundation of tonal structure.

With the multiplicity of tonal and non-tonal styles in a post-modern world,

Mehldau has at his disposal a variety of compositional choices. That he gravitates so

frequently to a nineteenth-century approach to tonality suggests that he simply chooses to

compose anxiety-free in a post-modern time. While some argue that composers today

can never regain the original fullness of common-practice tonality (one simply cannot be

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

29/235

16

in the eighteenth/nineteenth century), Mehldaus explicit pursuit of and indulgence in a

Romantic aesthetic challenges the twenty-first century composers acceptance of the loss

of the tonal tradition. What this study ultimately hopes to expose is how a tonal

theoretical system for analysis can apply to music of a post-tonal world, and potentially

what that says about its application to common-practice music.

Counter-example: Vince Guaraldis Christmastime is Here

Linear motion in modern tonal jazz is latent at times, which can lead to

problematic linear analyses. Often jazz music avoids the contrapuntal goal-directedness

that one would find in traditional tonal music. Consider the voice-leading of

Christmastime Is Here by Vince Guaraldi (1965), a popular song that, to my ear,

reflects the idiosyncrasies of tonal jazz during the 1960s (see example 1.3).

In the A section (which subsequently concludes the piece, and can represent the

final closing moments), the bass line arpeggiates the tonic triad by prolonging the

melodys A4through both tonic and subdominant regions. The bass line Stufenappear

normative upon first glance. There is a problem, however, understanding the

counterpoint between the melody and bass. How does one interpret the melodys

opening scale degree (7) in relation to the tonic bass? How does one interpret the tonic

scale degree belonging to the dominant bass in m. 7, beat 3? Finally, how do we

reconcile the ending ninth chord over the tonic?24

A traditional reading explains how 7 relates to the opening tonic: the opening

seventh chord is part of a descending (extended-tertian) arpeggiation of a tonic triad that

24. A similar issue is addressed in Michael Buchler, Laura and the Essential Ninth: Were They

Only a Dream?Em Pauta17 (2006): 5-25.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

30/235

17

leads to the more traditionalKopfton, 3, by m. 2. (Refer to the foreground and

middleground levels, example 1.3.) There is harmonic tension with the arrival of the

Kopfton, since the bass note descends a whole tone, to E flat. This transforms the arrival

of 3, A4, into the sharp-eleven of the E711harmony of m. 2. The E flat in the bass,

however, could be interpreted as an incomplete neighbor to the opening tonic of F. One

foreground detail exposes the cross relation of the E natural of the melody in m. 1 and E

flat in the bass in m. 2, drawing attention to this melodicharmonic problem.

Addressing how the eleventh belongs to the dominant (of a V11

in m. 7, beat 3) is

harder to explain in a traditional voice-leading context. The melodys arrival on F (1) in

m. 7 is indeed part of a three-measure prolongation of the subdominant. The F is

suspended over the dominant, perhaps implying a resolution to the leading tone. What

happens, instead, is an ascentto the ninth of the final F9chord in m. 8.

Another explanation (not shown) could suggest that the melody, through

arpeggiation down from 7 (E5) of m. 1, has taken seven measures to finally make its way

to the tonic (i.e., E5C5A4F4). This would require connecting the melodic F4of m. 7,

beat 3, to the tonic bass of m. 1: a highly skewed, and hyperbolized, representation of

tension concerning the Fs relation to the tonic bass. This reading, however, is not

supported by the events that take place starting at m. 5: a fairly dramatic shift to B-natural

in the bass initiates a 75 linear intervallic pattern that prolongs the subdominant. By the

time the melody arrives on F, it is effectively detached from its tonic origin of mm. 1-4.

The ending ninth over the tonic is essentially impossible to understand in a

traditional voice-leading analysis. While representing its own form of poetic closure, the

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

31/235

18

sentimentality expressed by the cozy F9harmony, a Schenkerian analysis cannot regard

that ninth as a form of closure, other than to pose a hypothesis that the final G in m. 8

represents a belated arrival of 2 over the dominant bass of m. 7 (via suspension), and that

the closure of the song is purposely denied. In example 1.3, I illustrate how the

normative suggested background becomes an open-ended version.

Example 1.3. Christmastime Is Here (Vince Guaraldi, 1965), A section, voice-leading

analysis

On the other hand, an alternate reading in example 1.3 (bottom-right of the

example, labeled ALT.) results in a highly atypical background: an ascendingthird

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

32/235

19

progression (which is in no way related to the foreground or middleground analyses of

example 1.3). In this alternate and unorthodox background, the opening melodic tone (7)

is prolonged over the tonic. This dreamy, tonic F7harmony resolves up from 7 to 1. In

this reading, 1 is not related to the tonic but represents the prolongation of the dominant

through a standard V11

chord. This subsequently resolves to an even dreamier tonic

harmony, F9, with 2 representing the ultimate melodic goal, the result of this melodic

ascent transcending a more normative resting place on 1. This background is

incongruous with traditional voice-leading analysis since the Urlinieresolves up, the

scale degree progression of the background is not typical of tonal music (712), and the

melody is not supported by triadic harmony. In a traditional analysis, the way I just

described the ascent past a normative tonic triad member suggests a passage filled with

tension, dissonance, and an improper tonal resolution. Yet the music does not reflect

such tension. I would argue the music is nostalgic, comforting, warm, the perfect music

for a wintertime carol.

Comparing the two backgrounds presents us with two fundamentally

incompatible voice-leading backgrounds in traditional Schenkerian terms. To recognize

that one background is derived from another (as in example 1.3), reveals a paradox of

tonality in Christmastime. The traditional tonal reading minimizes the events of the

song, characterizing it as essentially triadic in origin. The alternate background, while

more reflective of the song, on the other hand, is quite implausible in Schenkerian theory.

The alternate background of Christmastime provides a voice-leading picture

that does not lend itself well to Schenkerian analysis. Though a traditional Schenkerian

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

33/235

20

analysis might highlight unresolved tensions and dissonance, as in the alternate

background foil of example 1.3, the stylistic norms of jazz allow for poetic closure on a

major ninth chord: the dreamy feeling of Christmas time is timelessly epitomized in

Guaraldis progression.25

The music is not filled with tension, in spite of what traditional

tonal analysis might reveal. Indeed, had Guaraldi chosen to close on a tonic triad,

providing the kind of closure a Schenkerian analysis could identify with, the ethereal

quality of the music would be lost, the affective content rendered ineffectual. A palette

emphasizing harmonic color perhaps motivated Guaraldis melodic choices. The chordal

roots could have served as a template for any number of melodic/harmonic choices.

As much as I have analyzed Christmastime using a method intended for music

of the tonal era, an important feature of this song sets apart this music from traditional

tonal music: the melody appears derived from the extended tertian harmonies, and is not

concerned with consonance/dissonance conditions so important to Schenkerian theory.

The analysis required speculation about hidden functions of passing tones and

suspensions that led to some fanciful linear interpretations. The only unambiguous

neighboring note occurs in the bass, and serves as the primary hint of traditional tonal

tension. While this piece is tonal, it reflects a different dialect of tonality. Therefore, it

may prove fruitful to establish criteria defining tonality before proceeding with linear

analyses of jazz.

25. This is perhaps why, since 1965,A Charlie Brown Christmashas been televised every year,

transcending the musical changes that have taken place in forty years and serving as an important culturalicon in the United States.

There are other important factors to consider that are beyond the realms of tonal analysis: the

childrens choir suggests an endearing innocence that puts everyone in a sentimental mood during the

holiday season. Considering the descent from a fairly high pitch, E5, into an arpeggiation of a majorseventh chord, the childrens voices are never quite in tune. This does not detract from the performance but

indeed points to the innocence and youthfulness of the choir, and possibly encourages non-musicians to

join in without worrying about their own vocal ability.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

34/235

21

Harmony and Counterpoint (Historical Context)

Considering the historically contentious positions between melodic and harmonic

perspectives will help in establishing a useful definition of tonality. Some of the more

important historical landmarks should first be recounted. Jean-Philippe Rameau

developed the analytical distinction between seventh chords (called dominantes;

dominant sevenths were called dominante-toniques) and triads. He was attempting to

identify actualphysicalreasons for the generation of melodic motion in music.26

Rameau

countered the current trend, that melody was the incidental cause of harmony, instead

asserting that harmony drove melodic motion.

As influential as his tonic/dominant polarity was to compositional theory, his

original intent to demonstrate the implications of harmonic motion was lost over the next

few centuries. The kind of chordal analysis that Rameau inadvertently sparked over the

course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries can be traced to todays use of roman-

numeral analysis in the undergraduate classroom, which can mask the linear motion that

pervades classical music. Today, a student of jazz theory learns that a chord symbol is

available for nearly any collection of pitches. In jazz theory, only secondarily is there an

emphasis on traditional consonancedissonance-based counterpoint, let alone the kind of

recursivecontrapuntal voice-leading that Schenker discovered in his theories.

Schenker attempted to reinvigorate contrapuntal laws to remedy the static

description of roman numerals, and, further, to show that contrapuntal models were

recursive by nature. He developed his analytical techniques from the masterworks of

26. In particular, Rameau imparted to his readers that pitch followed the same scientific principles

as light, particularly those principles discovered by Newton. See Thomas Christensen,Rameau and

Musical Thought in the Enlightenment(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-44.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

35/235

22

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To be sure, Schenker probably never would have

applied his analytical techniques to jazz music. But while it is easy to assert such a

dismissal based on the more obvious cultural differences between jazz and classical

styles, it is not without justification: a large body of tonal jazz is notconceived

contrapuntally.

Mehldaus music, however, isconceived contrapuntally, as he himself states and

as can be analytically demonstrated. This characteristic allows him to explore a tonal

world similar to that of German romanticism. Mehldau shares an affinity to the reckless

counterpoint found in the music of Schumann, the intense modes of expression of

melodic tension like that of Mahler, and the enigmatic treatment of tonal elements like

that found in the music of Chopin or Brahms.27

Defining Tonality

Henry Martin has argued that twentieth-century music tends to be inconsistent in

establishing itself as either tonal or atonal.

28

Indeed, the content of much music of

Hindemith, Shostakovich, Bartk, and Copland (among others) can enter into both tonal

and atonal contexts. Martin, in his attempt to refine our understanding of tonal versus

atonal grammar, presents nine tonal cues that are shown in roughly decreasing order of

importance (figure 1.1).29

Martins fifth cue seems to be the strongest evidence to

support the assertion that Christmastime is tonal: presence of Stufenarising from

27. My reference to reckless counterpoint comes from Bo Alphonce, Dissonance and

Schumanns Reckless Counterpoint,Music Theory Online0, no. 7 (1994), http://mto.societymusictheory.org/issues/mto.94.0.7/mto.94.0.7.alphonce.art.html (accessed January 28, 2010).

28. Henry Martin, Seven Steps to Heaven: A Species Approach to Twentieth-Century Analysis

and Composition. Perspectives of New Music38, no. 1 (2000): 129-68.

29. Ibid., 132.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

36/235

23

hierarchical, nested prolongations that ultimately give rise to tonal center and key.30

His

second and third ranked cues, on the other hand, create difficulty in asserting that the

song is tonal: absent is a normative dependence of dissonant intervals on consonant

ones, and whether one reviews the foreground analysis or the alternate background, and

the music does not fit the criterion of functional harmonic succession based on triads,

since it is mostly based on extended tertian harmony.

The succession of Stufenin Christmastime shares many similarities with

traditional tonal techniques inherited from the Western tonal tradition, but yields no

further evidence that the melodic material follows the contrapuntal norms Schenker

codified. While Schenker ultimately used his analytical method to evaluate artistic merit,

I am using it to demonstrate how the tonality of modern jazz differs from the kind I

will examine in Mehldaus music, where, I argue, there is a traditional relationship

between bass and melody. The tonality of Christmastime contrasts with the kinds of

tonally directed melodic motions found in Mehldaus music.

Figure 1.1. Henry Martins tonal cues in twentieth century music

1. principal pitch-class collections usually reducible to major or minor scales;

2. normative dependence of dissonant melodic intervals on consonant intervals

prolonged at a higher structural level;

3. functional harmonic succession based on triads; in two-part writing, on

consonances that may imply functional harmonic succession

4. harmonic rhythm arising from functional harmonic succession;

5. presence of Stufenarising from hierarchical, nested prolongations that

ultimately give rise to tonal center and key;6. norms of melodic writing in which conjunct intervals predominate;

7. half, full, and deceptive cadences;

8. meter;

9. phrase and section groupings that project two-, four-, and eight-bar

symmetries.

30. Martin, Seven Steps to Heaven, 132.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

37/235

24

Returning to Martins tonal cues, I would contend that jazz music follows only a

selected part of his list, whereas Mehldaus music follows all of them. If one were to

measure the degree of tonality in jazz music, one may be comfortable with the

characterization that most tonal jazz has meter, and from that, phrase and section

groupings that often project two-, four-, eight-, sixteen-bar and larger symmetries. On

the other hand, most tonal jazz music departs from displaying normative dependence of

dissonant intervals on consonant intervals prolonged through higher structural levels

(Martins second-most important tonal criterion in figure 1.1).

The third criterion is also atypical of much tonal jazz music, since jazz is

not based on triadic harmony, nor can that harmony be revealed when boiled

down to two-part writing. These criteria can help draw a distinction between the

tonal language evident in Mehldaus music and, say, the music of Bill Evans (see

chapter 6). Many examples of tonal jazz music that seem amenable to

Schenkerian analysis follow Martins criteria 1, 4, 5, 8, and 9 (extracted into

figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Martins criteria for tonality as typified by tonal jazz

Harmonic rhythm arising from functional harmonic succession;

Principal pitch-class collections usually reducible to major or minor scales;

Presence of Stufenthat ultimately give rise to tonal center and key;

Meter [note: previously Martins eighth cue];

Phrase and section grouping that project two-, four-, eight-, twelve-, sixteen-,

or thirty-two-bar symmetries.

The remaining criteria repeated in figure 1.3 do not seem to be followed

consistently in modern tonal jazz music. Melodic writing is frequently disjunct,

as a result of emphasizing chordal arpeggiations within extended tertian

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

38/235

25

harmonies; tonal jazz music emphasizes extended tertian chords;31

dissonant

intervals are independent from consonant ones; and cadences are variable in the

jazz idiom (many IIVI progressions are not in the home key, and traditionally

full cadences imply a resolution to a tonic triad, which is atypical in modern jazz

practice).

Figure 1.3. Martins criteria for tonality exempted from modern jazz

Normative dependence of dissonant melodic intervals on consonant intervals

prolonged at a higher structural level

Functional harmonic succession based on triads;

Norms of melodic writing in which conjunct intervals predominate at deeperlevels;

Half, full, and/or deceptive cadences.

Another useful set of tonal criteria is provided by Joseph Straus. His definition

(with minimal revision) will serve as the basis for my approach to Mehldaus music,

including the historical context into which I believe Mehldau places his music. Straus

writes:

Traditional common-practice tonality, the musical language of Western classical

music from roughly the time of Bach to roughly the time of Brahms, is defined by

six characteristics:

1. Key. A particular note is defined as the tonic (as in the key of C or the keyof A) with the remaining notes defined in relation to it.

2. Key relations. Pieces modulate through a succession of keys, with the keynotes

often related by perfect fifth, or by major or minor thirds. Pieces end in the keyin which they begin.

3. Diatonic scales. The principal scales are the major and minor scales.4. Triad. The basic harmonic structure is a major or minor triad. Seventh chords

play a secondary role.

31. This observation is supported by James McGowans study on what defines consonance intonal jazz music; he adapts the idea of consonance as being a triad with the addition of a fourth member, an

added sixth, a major seventh, or a minor seventh (see also n. 15supra). James McGowan, Consonance

in Tonal Jazz: A Critical Survey of Its Semantic History,Jazz Perspectives2, no. 1 (2008): 69-102.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

39/235

26

5. Functional harmony. Harmonies generally have the function of a tonic (arrivalpoint), dominant (leading to tonic), or predominant (leading to dominant).

6. Voice leading. The voice leading follows certain traditional norms, including

the avoidance of parallel perfect consonances and the resolution of intervals

defined as dissonant to those defined as consonant.32

Of course, not all tonal music from the time of Bach to Brahms always follows

these principles to the letter. Many interesting moments throughout the history of tonal

music occur when these principles are notfollowed. Nonetheless, they represent norms

from which departures may be clearly marked as such.

As clearly as tonal principles operate in Mehldaus music, the music itself is open

to unexpected possibilities, such as an off-tonic opening. Returning to 29 Palms

(example 1.4), the piece appears to begin in the key of C major, but by the final cadence

(m. 16) the music has modulated to B major. In fact, it is not clear whether 29 Palms

begins off-tonic and corrects its course by the arrival of tonic in m. 4, or if the piece

begins inC major and gradually modulates to the distant key area of B major.

During an introductory vamp, Mehldau adds an anacrusis G in the bass (not

shown in the score, but illustrated in example 1.5). This effectively establishes the key of

C major with a common blues idiom. After the vamp, however, something rooted more

in the classical style emerges: a chromatic descending bass (example 1.5). The chromatic

descent of the first four bars makes the arrival at B major all the more unexpected.

32. Joseph N. Straus,Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Prentice-Hall, 2005), 130.

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

40/235

xample 1.4.

xample 1.5.

29 Palms,

29 Palms,

m. 128 (

m. 14, ha

27

and B sect

monic reali

ions), with

zation and

orm annota

nalysis

ions

D.C. al

fine

fine

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

41/235

28

Without absolute pitch, the listener might justifiably be confused as to the

concluding harmony in B major. First, we hear C major in m. 1. In m. 2, mixture brings

a sense of flat keys into the foreground, which can be interpreted in B-flat major.

Following the IV6in m. 3, though, the bass descends one more semitone, which poses a

problem of enharmonic interpretation: If heard in C major, is the chord a secondary

dominant of B (VII) or C flat (I) major? If analyzed in B flat major, is the chord a

secondary dominant of C flat (II) or B (I) major? The shift, while abrupt, retains a

common tone in the melody: E flat becomes the thirteenth of the G7harmony (m. 4)

before resolving to C flat notated as B major (often resolved as a triad, despite Mehldaus

own indicated chord symbol of B7). Note that Mehldau himself seems unsure of the

enharmonic solution, as he indicates chord symbols from both keys, C flat and B major,

in the progression G7to B7.

Had the E flatD sharp resolved down by step to C sharp, this resolution would be

identified as a normative suspension. Nor would a jazz composer have likely employed

this type of tonal shift to B, based on norms of jazz voice-leading. For instance, if a jazz

composer were given the first three bars of 29 Palmsand were asked to finish the phrase,

the adept composer would recognize the move to the flat side in mm. 23, and possibly

conclude the phrase with a cadence to C minor, while incorporating typical jazz harmony

(example 1.6).

-

7/13/2019 155711492-Aruthurs-2011-Mehldau

42/235

29

Example 1.6. 29 Palms, mm. 34, hypothetical phrase ending in C minor

Mehldau isaware of the mixture toward C minor, as he continues throughthe B

major arrival at m. 4 and tonicizes C minor by m. 6 (refer to example 1.4). The phrase

ending signified by the melodic repose of m. 4 competes with the bass lines descending

momentum. This continuation propels the harmonic progression forward, and departs for

the present to B major.

When I first referred to 29 Palms, I illustrated how this piece features

contrapuntal treatment of pitch materials, particularly in the final cadence of m. 16

(example 1.2). This cadence differs from a typical cadence of the tonal era in that there is

no root position dominant to root position tonic, though the final chord is a triad (which,

again, stands apart from typical jazz resolutions, often permitting added sixths, sevenths,

or other extensions). Considering that the identity of the piece is defined by a stepwise

descending bass, it becomes clear that an unfolding of the root position dominant