14 T h e C a rl C h in n p a g e When MamaÕs

Transcript of 14 T h e C a rl C h in n p a g e When MamaÕs

14 Express & Star, Thursday, March 1, 2007

guage. “One thing she did say that was my

dad was the loveliest of the lot and hewas a lovely man, a really lovely man.”

Iris’s mother was Amy, nee Clamp.She was an Englishwoman and used todo most of the ice-cream making.

BucketsThe family lived in Graiseley Street

“in a little, teeny two-up two-down inwhich Mom raised the five of us wholived (she lost one as a baby).

“That left me, Bill, Carmine, Sylviaand Stephanie. We shared a yard withthe next door neighbour. Mom hadnothing to do with the ice-cream origi-nally and wasn’t brought up in it butshe used to go in the yard to a properice-cream making place with tileswhere she’d boil it up to make it andthen put muslin over galvanisedbuckets to protect it.”

There are still Leos in the ice-creambusiness in Wolverhampton and once

there were many like them in the WestMidlands. These families arrived herein the late 19th century, when theeconomy in southern Italy collapsedand hundreds of thousands fledpoverty.

Most of them headed for the USA,but a few came to Britain. In Glasgowand Edinburgh there were largenumbers from the commune ofPicinisco, in the province of Caserta.

This was part of Campania andbelonged to the region of Naples. It layin the mountains above the River Liri,south of the larger town of Sora andnorth of Monte Cassino.

Nearby were the communes of Atinaand Gallinaro, and closer to Sora wasthe village of Carnello. This area waswhere the Leos came from, as did themajority of Italians who settled inBirmingham.

Winifred Mullane’s mother camefrom Carnello and her father from SanVincenzo, to the north of Sora. Theyrecalled that the land was owned bypadroni, who employed whole familiesforming small villages.

Work on the farms and in the vine-yards started “about 4am until noonbecause of the heat”.

The lives of women were especiallyarduous. The younger ones toiled withthe men, and “many babies were bornin the fields and some mothers workedright away” after the birth of their chil-dren.

Older women went to church eachmorning and then did the washing inlocal streams as “bed sheets were driedand replaced everyday”. After thesiesta, at about four o’clock in theafternoon, all the women prepared theevening meal, “killing two or threechickens running around the farm,making spaghetti and bread, cookingamong fire stones”.

For Beattie Eastment’s grand-mother, bread itself symbolised the dif-ference between Italy and England.

“Granny Volante used to say howhard her mother-in-law was and sheused to say ‘Oo, the bread! – we used tohave to eat black bread’.

“And do you know it didn’t matterhow much money she’d got, she wouldget a piece of bread, dry bread, and eatit. And I used to say, ‘Gran, what arey’doing that for?’, and dip it in her tea.I used to say,’Gran, what are y’having?’and she used to say, ‘Oh”, in her way oftalking in broken English, “It’s mar-vellous bread compared to what weused to eat, black bread”.

The earliest Italians from the MonteCassino region who settled in the WestMidlands came to Birmingham andwere mostly musicians.

LodgingIn 1881 a Giuseppe Delicatto was

recorded as a street musician living atthe back of 33 Bartholomew Street. Hiswife, Maiscatta, was aged 19, and their15-month-old son had been born inBirmingham. Lodging with them were15 street musicians, ranging in agefrom 17 to 58, although the majoritywere in their late teens and twenties.

Only one of these people was Englishand the rest were Italian. Among themwas an Antonia Frezza, whose familyremain in Birmingham.

Ten years later the census recordedanother Delicatto with another lodginghouse in Bartholomew Street. Herented accommodation to 22 organgrinders and other street musicians,three of whom were from one family –Anne, Maria and Filamina Volante.

At 33, Bartholomew Street now livedTomas and Mary Volante. They had aseven-year-old boy who was born inBirmingham; and they gave room totwo lodgers – Mary and Pasqua Deli-cata, who was aged thirty and workedas a hawker.

In the courtyard behind this addresslived Antonio and Antonia Tavolier, inthe house occupied in 1881 byGiuseppe Delicatto and his lodgers.Antonio was born in 1863 in thecommune of Atina. His birth had been

registered by another Giuseppe Deli-cata, a farmer.

The Tavoliers claimed they werepre-eminent in the movement fromGallinaro and Atina, asserting that “ifit weren’t for us, half of em’d still be upthe mountains”.

This was an exaggeration, but thereis little doubt that the family’s resi-dence in Birmingham encouraged theemigration of some of their relatives.

ArrivedAntonia Tavolier was a Bove by

birth, and by the turn of the centuryshe had been joined by her brotherPeter and other members of theirfamily. Similarly, in 1892 the family ofVincente Volante arrived in Birming-ham.

As his granddaughter remembered,“our grandad went to America firstbecause his brother was there, PeterPaul. But he didn’t like it. So he camehere where his other brother was,Cecedio, and settled nearly next door.”

These pioneering families were fol-lowed by others from their district:Pasquale and Angela Verechia; theReccis; the Farinas; the Secondinis;and Martino Changretta, who wasthought to have come with a Volante.

In a strange land the Delicatas,Tavoliers and Volantes provided asupport system for these newcomers.Importantly, they also establishedBirmingham’s Italian Quarter as aplace which was dominated byNobladans – speakers of the Neapoli-tan dialect. As a result, Birmingham,along with Walsall and Wolverhamp-ton, was an attractive destination to allsouthern Italians.

MandolinsThus the emigrants from Gallinaro

were joined by families from othercommunes in Caserta. The Bianchiscame from Peschosolido, north east ofSora; the Grecos and Iafrattis bothoriginated in Carnello; and VincentPontone and Enrico Facchino bothstated they came from Sora itself.

It appears that Bristol was the portof entry for some of these southernItalian immigrants, as Jackie Tam-burro brought to mind. His father wasfrom Atina, as was his wife and herbrothers – the Fiondas.

In the early 1900s they settled inBristol as an extended family group,“and they used to go around the cityplaying the mandolins and the organsand my one uncle had a big brown bear.It used to dance on his hind legs”. If theaudience was appreciative, “the peopleused to drop the money in the cup andthey used to keep this bear down thecellar”.

From Bristol, Jackie’s parentsmoved to Preston. This was the basefrom which Felipo Tamburro “wouldgo to different towns playing his accor-dion, you see. Busking as we call it. Andhe used to come every now and againand bring the money”.

During the mid-1920s, the familymoved to Birmingham where Felipo’s

When Mama’swas the ideal

TThhee CCaarrll CChhiinnnn ppaaggee

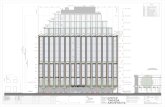

PAT Finerty of Oxley Moor Road, Oxley, has written into encourage me “next time you are at the MolineuxHotel, to just look across the ring road towards the

Civic Centre. The building on the right is St Peter and Paul’sRoman Catholic church. It is identical to the hotel.

“It was built to look like a house and the word is it had tunnelsfor the priests to escape. The Millner Hall adjoining it was a greatvenue for the Irish in the 1950s. It was named after Bishop Millner.

“Carl, one more thing. My mother-in-law is a daughter of PercyLeo, whose family are famous for ice-cream making.

“She is Iris Hodgkiss and she tells us about when they made theice-cream in the backyard and then went off on the motorbike withthe tub of ice-cream in the side car – off to the local fairs to sell it.”

Iris was good enough to let me chat with her about her family. Sherecalled that her father used to say something about his parents comingfrom around Monte Cassino, where the big battle was fought in theSecond World War, and that some of the family had gone to America.

Unfortunately Iris’s grandfather died before she was born, but shedoes remember her granny, “a lovely old lady. We couldn’t talk muchto her, though, because she used to start off in English and go intoItalian and we couldn’t speak the lan-

JHALFORD has kindlypointed out my errorin locating this photo,

used a few months back. Isaid it was Molineux Streetby Herbert Street but “is infact North Street notMolineux Street whichleads off to the right of thepicture.

“The shops on the rightare part of Tin Shop Yardwhere the fish and chipshop stood. The buildingopposite, next to thedouble gates became theFox Hotel which is stillthere today, and HerbertStreet is actually offStafford Street.

“I lived in Middle Row inthe 1930s, off CharlesStreet, which is now thering road. I used to walkalong the Lonnes to RedCross Street School – it wasan alleyway parallel toNorth Street. Hope thisputs things right.”

John Lagorio with his cart in late 19th Century Birmingham’s Bull Ring

North Street, Wolverhampton, with Molineux Street leading off to the right

Memory of life in the Middle Row

Have you a story to share about theBlack Country? If so drop Carl a note.If you have a tale to tell, a memory topass on or a photo to share then writeto Carl c/o the Editor, Express & Star,Queen Street, Wolverhampton, WV11ES. All photos will be scanned imme-diately at the Express & Star officesand returned as quickly as possible.You can also e-mail Carl [email protected]

You can hear Carl Chinn eachSunday on BBC WM 95.6 FM

between 1pm and 4pm

Writeto Carl