13028 DVD booklet - Stefan Grossman's Guitar · PDF fileof blues performers with whom King had...

Transcript of 13028 DVD booklet - Stefan Grossman's Guitar · PDF fileof blues performers with whom King had...

2

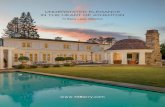

FREDDIE KINGJANUARY 20TH, 1973 – DALLAS, TEXAS

by Mark Humphrey

Freddie King’s odyssey began in the small Texas townof Gilmer, roughly midway between Dallas and Shreveport,on September 3, 1934. A different notable odyssey wouldbegin just 19 days later when the recently-freed Leadbellyentered the service of ‘ballad hunter’ John Lomax inMarshall, Texas, only a few miles south and east of Gilmer.Other journeys traversing the Lone Star State that yearinclude that of a young Lightnin’ Hopkins on the road withitinerant blues singer Alger ‘Texas’ Alexander, whose OneMorning Blues was recorded (without Hopkins) in FortWorth 27 days after King’s birth:

One morning, one morning,When God began to break His day,I was sitting here wondering,Where is my babe today?

King first saw light as one generation of Texasbluesmen was passing the torch to the next. The rural andreflective imprint of Alexander and Blind Lemon Jeffersonwould remain tangible in a younger generation’s countryblues popularized on record after World War II by Lightnin’

3

Hopkins, Lil Son Jackson and Smokey Hogg. Raw andatavistic, their performances became parting backwardglances, last hurrahs of a powerful tradition. But evenbefore they recorded their stark and final music, T-BoneWalker was already changing the shape of Texas blues withamplification, a flawless sense of swing and abundantextroverted panache. He would become the role model fornearly every Texas-born blues singer-guitarist (AlbertCollins, Gatemouth Brown, etc.) of King’s generation. Thefact that King didn’t sound more like T-Bone than he didmay be due to a twist of geographic fate: when he wasabout 15, he moved with his family to Chicago.

He took with him memories not only of rural Texasblues but also of the loping gait of Western Swing (“Hehad this thing about westerns!” King’s daughter Wandarecalls) which would later imbue Hide Away, a closerelative of Steel Guitar Rag. King carried further memoriesof recordings and radio broadcasts by Louis Jordan, whosesaxophone riffs he sought to replicate on his guitar. (Thatmay account for his always playing with distortion, longbefore it was fashionable.) And what he brought to Chicagowas matched by the power of what, in 1950, he found there:the post-War Chicago blues scene in full swing.

Big for his age, King hung out and soon won theapproval of the reigning blues monarchs (“Muddy used toslip me into the Club Zanzibar,” King recalls in this video).In time he was playing with them, absorbing lessons ofshowmanship and stagecraft from Muddy Waters andHowlin’ Wolf as well as lessons in guitar subtleties fromthe scene’s ace accompanists, Jimmy Rogers, Eddie Taylorand Robert Jr. Lockwood. He took it all in and it’s temptingto call King’s blues style a fortuitous blend of Texas rootswith tough Delta distillates served straight in Chicago’sblues bars. That’s half true at least.

But what of his pleading ‘churchy’ vocals that suggestB.B. King and Bobby Bland and a Memphis-based schoolof blues performers with whom King had no known contact?What of the instrumentals, suggesting country at one endand funk at the other and no where much the blues ofChicago? Much as we’re tempted to peg bluesmen by genreand region, Freddie King can’t easily be slotted, even asan anomalous Texan-gone-to-Chicago (the usual Lone Staremigration route led to California). He was more than

4

merely the sum of hisevident par ts (oraddresses) and onemight hai l King asperhaps the first post-modern bluesman, aneclect ic who tran-scended the music’sghettoization by freelymixing musical med-iums that had less to dowith where he was fromor where he was at thanwith how far he waswilling to go.

By such meansKing got his blues towhite teens who justwanted hot instrumentaldance records for theirpar ties. Many of thekids who danced toHide Away in 1961were indulging in less innocent recreation a half dozen yearslater when they grooved to Jimi Hendrix’s Purple Haze,but did not have the impact of King’s blues-based (but notstrictly blues) instrumentals opened a door to Hendrix’spsychedelicized blues-based explorations? Certainly thecontent (and context) of Freddie King’s happyinstrumentals of the idyllic Kennedy years and Hendrix’sangry/erotic Vietnam-era visions are radically different, yetboth used blues as a core around which to wrap elementswhich no literal bluesman would venture to add. Could wehave been as receptive to Hendrix had we not first dancedto Freddie King?

King wasn’t yet 30 when he returned to Texas intriumph, a hit-maker on the Cincinnati-based label withwhich he shared a surname. (His singles appeared onFederal, a subsidiary of the label on which his ‘dance party’albums were released, King.) He settled in Dallas,establishing himself both on the local club circuit and as atouring presence throughout the Southwest. His steadyreliability and unfailingly sharp showmanship served King

5

well on his local turf when the hits ceased in the mid-1960s.Even in the late-Sixties lull before his rejuvenatingassociation with Leon Russell’s Shelter label in 1970, Kingkept busy. There was a brief stint with Atlantic/Cotillion in1969, followed by his ascendancy on Shelter as a‘rediscovered’ bluesman once again celebrated by the samefans who had bought Hide Away not quite a decade earlier,though seemingly in an era rather more remote.

It was no great stretch for King to play ‘heavy’ blues,as he did on 1970’s Going Down, his best-known songfrom his Shelter era. Watch him skillfully using volume anddistortion on the video of The!!!!Beat (Vestapol 13014),performances from 1966. ‘Heavy’ was an implied part ofhis trademark sound, even on many of his early 1960sFederal singles. King had little trouble adopting to the tastesof his new audience (“...the Fillmore circuit wasn’t reallyhard for me,” he said) and he was both willing and able tokeep his music contemporary. He was a blues singer-guitarist who had been a name for a decade, but the lastthing he would be was an ‘oldies’ act. More to the point ofthe performance on this video, King wasn’t unresponsiveto devel-opments in contem-porary black music, even ifhis 1970s audience was largely white. The early 1970s wasthe golden age of funk and the performance King and hisband served to the Dallas PBS station in 1973 wassupremely funky.

“The unique thing about my father,” recalls WandaKing, “is that he was always contemporary, so it was noeffort for him to get funky!” Indeed, such instrumentals as1961’s San-Ho-Zay sound, in retrospect, like blueprints forthe funk groove booted to stardom in 1965 by JamesBrown’s Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag (King performed aninstrumental version of Brown’s song on The!!!!Beat). WhenKing appeared in Dallas, funk was everywhere: StevieWonder’s Superstition was peaking, Bill Wither’s Use Mewas a recent memory and so was Soul Brother # 1’s GoodFoot. At the time (pre-disco) funk was not really all thatfar removed from its blues roots: you can hear ancestralfunk in the snapped bass lines and shifting rhymthicaccents of Charley Patton’s 1929 Delta blues recordings.So for Freddie King to ‘get funky’ was both an affirmationof what was happening in the most exciting pop music ofthe day and a reflection of African-American tradition.

6

I t went down (as you can see) l ike this: Theperformance opens with a tearing paean to a Big-LeggedWoman (in a Short, Short Mini-Skirt). The funk is thick onthis band showcase that demonstrates what anextraordinarily tight unit (the rhythm section especially)supported King. Having lobbed this grenade, King knew toback off next, pacing himself (and his audience) with ablues-ballad, Jimmy Witherspoon’s Ain’t Nobody’sBusiness. But there's no containing his powerhouse vocals,intense enough to overpower and distort his microphone.

Elmore James’s Look on Yonder Wall (recorded thesame year King had his Hide Away hit, 1961) is funked upproud, lyrically updated with a Vietnam reference and shedsa spotlight on the bass playing of King’s brother, BennyTurner. By contrast, Bill Withers’ 1971 hit, Ain’t NoSunshine, is movingly understated and features a sparebut powerful guitar solo.

In the early 1970s, the boogie was, as Canned Heatnoted in the title of an extended jam, endless. “Boogie”became a verb for stoned partying and to play a boogiewas de rigueur for every electric blues band. So if he mustboogie, then Freddie King would boogie harder and morefrantically than anyone with his Blues Band Shuffle, avariation on the hypnotic vamp that made a hit of JohnLee Hooker’s 1948 Boogie Chillen. King churns the boogieup from the level of trance to one of pandemonium,

7

unleashing drummer Charlie Robinson on a stops-out solo.Characteristically, he graciously acknowledges the powerof his band (“How ‘bout Charlie on the drums?”).

Having put the band and audience through a wringer,King proceeds to testify, to pose a dramatic moral dilemmain Have You Ever Loved a Woman. The song was his firsthit in 1960 and he continued performing it with intenseconviction throughout his career. A decade after that initialsuccess, Going Down brought Freddie King new life and anew audience: Here he and his band hammer and nail his‘comeback’ song without letup or mercy. Finally, theperformance ends with the tune that was King’s signature,of which British blues writer Dave Williams observed: “Itmust have served as a set opener for more gigs than anyother tune in R&B history.” He referred, of course, to HideAway, which here takes some surprising turns as it’sextended and given a funk section, King’s way ofintroducing his past glory to the music of the moment.

And it was a truly exhilarating moment, a burningperformance easily the equal of any captured on theVestapol trilogy of Freddie King videos, the others beingFreddie King in Concert (Vestapol 13010) and Freddie King:The!!!!Beat (Vestapol 13014). There’s no saying, over 20years later, just why certain performances glow with theexcitement of everything in sync, of musicians playing attheir peak and sometimes seemingly beyond it. Maybe itwas simply a good night; maybe everyone was inspired bythe knowledge that the performance was being broadcastin Dallas, King’s hometown (his affinity for it was celebratedin the Shelter-era song, Palace of the King). Maybe it’s notreally worth analyzing, or comparing this performance withany others in the video trilogy by this same band. It’s bestto just savor the moment, knowing that King’s time wastragically short (not quite four more years after thisperformance), and that it was probably for just suchmoments that he lived.

Freddie King’s life, legacy, recording career andinfluence have been documented in the booklets to theaforementioned videos as well as in CD liner notes andelsewhere. Too often he’s carelessly lumped with ‘the bluesguitar-playing Kings’ and regarded with less seriousness(perhaps for being less rigorously bluesy) than B.B. orAlbert King, none of whom were related. Had he kept his

8

surname at birth, Christian, instead of taking his mother’smaiden name, King, subsequent to what his daughtercharacterized as a “family feud,” would we think differentlyof King? His talent wasn’t one which suffered by honestcomparison and while there’s no denying the ‘blues power’of Albert or the ‘boss o’ the blues’ credentials of B.B., itwas Freddie who first crossed over to white audienceswithout really compromising his music. We could inviteFreddie to play at our sock hops and via record anyway,he never failed to show up and party. On January 20, 1973,those of us in central Texas ‘got funky’ with Freddie via TVonly days before the signature of a peace agreement endingthe war in Vietnam. It was quite a moment and FreddieKing was a dynamic part of it for many of us. His power iswith us yet in this video performance: January 20th, 1973– Dallas, Texas.

9

DIRECTOR JIM ROWLEYREMEMBERS FREDDIE KING

Interview by Mark Humphrey – August 1, 1994

If you have small children, you’re familiar withtelevision director Jim Rowley’s work from Barney &Friends. Before Barney, Rowley explored his passion formusic and video in the 1960s at channel 8 in Dallas, wherethe legendary R&B program The!!!!Beat was shot in 1966.(Rowley did not direct or edit the Freddie King segmentsof that show featured in the Vestapol video Freddie King:The!!!!Beat.) Rowley moved into public television in the1970s, which afforded him the opportunity to produce theperformance on this video. He recalls the circumstancesin the following interview.

JR: There’s a local station here (Dallas), KERA-TV, channel13. I left channel 8 I guess in 1972 to go to work over thereas production manager. One of the things I was able toinstitute as an ongoing thing was a program called FreeStage. It was a combo effort between channel 13 and oneof the local FM stations which would broadcast our concertsin stereo. Simulcasts were kind of new and we felt like wewere out there on the leading edge of things. So we didfour or five of these a year I guess and Freddie Kinghappened to be one of those. Others, we did one with WillieNelson, we did one with other regional bands who werepretty hot. Blood Rock was the name of one band, I think.It’s been a long time ago! (laughs) And it wasn’t allnecessarily the kind of music I listened to when I wenthome.

MH: Was Freddie King?

JR: Oh, yeah, sure. I like the blues. That’s good stuff.

MH: He had quite a presence in Dallas, didn’t he?

JR: Oh, very much so. He was very big here. He’d drawbig crowds. Couldn’t tell it by our little show, because weworked in a little tiny, tiny studio, so the folks that werepresent were really just acquaintances of folks working onthe show. But we never intended to shoot it as an audienceparticipation show anyway.

11

MH: One thing that struck me about this performance isthat the band was really playing hard. I wondered if thatwas because they were home and playing for a localaudience?

JR: Well, I guess that could be. We weren’t really able tosupply him with much of a live audience to really respondto. Something in my memory tells me that these showswere live, but when I look back at the photos and stuff wedid, I think we did all of that kind of stuff the day prior. Weinterviewed him and did the still photo shoots and that kindof stuff, then put ‘em in those little white frames to make‘em look like photographs. We may well have laid those inlive as we did the show that night, ‘cause as I recall thoseshows were done live. I don’t think we went to tape with‘em and then did a lot of editing. They were pretty much‘what you get is whatcha got.’

MH: Two or three cameras?

JR: Three cameras in a little tiny space, which you can tella few times in there how small things are. We got awaywith some stuff that we shouldn’t have gotten away with:Cameras rolling in front of other cameras and stuff, butwhen you keep in mind the kind of freewheeling atmospheremusic shows were in those days, that kind of activity wasreally very acceptable. It was not surprising to see thatkind of stuff.

MH: There was some arty, psychedelic camera work.

JR: Yeah and all the guys who were working on the showwere definitely out of that school of belief. We all came outof the 1960s and we all got converted by the Beatles. Andto a large extent people who worked on that show actuallyhad followed me from the commercial station where I hadworked where we had done a lot of rock ‘n roll TV prior totelevision becoming more information-based in the early1970s, which is basically why I left commercial televisionand went to public television. I had flourished as anentertainment director in the 1960s; I had the opportunityto do a lot of music, including The!!!!Beat, which were donein 1966. In the middle 1960s I was doing a daily ‘Bandstand’show and a weekly music show that appeared on Saturdaynight. I was really into music and television as a

12

combination thing. Anyway, alot of the guys who had workedwith me at channel 8, when Iwent to channel 13, I took a lotof those folks with me. Theywere part of that crew that shotthe Freddie King thing.

MH: How had Freddie changedsince The!!!!Beat?

JR: Frankly, I couldn’t speaktoo much to Freddie himself.The show we taped with himwas my first lengthy exposureto him and his music. I wascer tainly aware of him.Growing up in the Sixties, youwere aware of B.B. and Freddieand Albert, all the King boys.

And I was somewhat familiar with a piece or two of hismusic, but I wasn’t really a follower at that point. So I’dhave to say that the show was a singular music event inmy life, in my career. I didn’t have a lot to go on beforehandand of course, Freddie was not with us for a long time afterthat show.

MH: Anything about him or his band that stands out inyour mind?

JR: Well, yeah, a couple of things. I think his name was(David) Maxwell, the piano player. Even in those days itseemed to me an oddity that this guy would be playingpiano with a blues band like Freddie King’s. But he certainlylent a unique visual impression to the whole evening sittingover there. And evidently he had been with Freddie a longtime and was with him till the end. The drummer (CharlieRobinson), I remember I had a long conversation with thedrummer that night before we started taping and he wasreally hyped up and ready to go. I recall watching him thatnight and perhaps because in cutting pictures to musicyou spend a lot of time dealing with rhythm, I kind ofassociate with bass players and drummers and that-wholerhythm aspect thing. And I was fascinated by this guy, hewas an extremely good drummer and really right with it.

13

And then Freddie, just Mr. Cool, you know. We hadinterviewed him the day before, the photo session tookplace there in a room at the station and we talked with himon audiotape and my still photo-grapher took pictures ofhim simultaneously while Freddie told us stories from theroad and gave us some background that we could edit andput together to go into those two or three places that weactually used it in the show. And he was just a real sweetguy, a prince of a man who was there to do anything weneeded to get done. He was ready and willing to sit downand be interviewed and do anything we needed. He wasalways quick to smile and always had a little tale to tell. Iremember him with great fondness and I really did enjoyhis music as well. I won’t sit here and tell you I’ve got theentire Freddie King collection in my living room, but Icertainly became a fan as a result of that experience withhim.

MH: Were there reactions in Dallas to the show?

JR: Specifics I don’t recall. Generally speaking, the wholeseries was pretty popular here in the region. It ran about ayear and as I recall we did five shows. I think I left channel8 and came over to channel 13 in 1972, so I believe theykind of (span) portions of 1972 and 1973. Then I leftchannel 13 a year after I got there and went on into thefilm business and did some other things.

MH: And where are you now?

JR: I’m the senior producer of Barney & Friends on PBS.We have done 48 shows which I directed and we’re gettingready to do another series of 20. I’ve moved up to seniorproducer. I’ve been doing Barney the last two or three yearsas a freelancer and I took a job with them this summer. SoI’m now an employee for the first time since I left channel13 in 1973. So for the first time in 21 years I’m taking ajob someplace. That’s kind of scary, isn’t it?

MH: Thanks for sharing your recollections of one of thehottest nights of Freddie King’s music to survive on video.

JR: Oh, man, he was cooking that night! That band, theywere on, they were tight and it still shows today when youlook at that performance.

14

MH: They were just burning through the whole thing.

JR: Absolutely cooking. One of the things that might havehelped, now that I think about it, was that we were in asmall room and it was in a TV studio, so it was ‘soundfriendly,’ if you will. In a nice enclosed space like that itwas very intimate with the few people who were therewatching and the cameras were in kind of close and it wasreally like being in a club atmosphere, which, when it’s allsaid and done, I would imagine that’s probably whereFreddie felt most comfortable, in the kind of situation hestarted out in and learned it all in, as opposed to the Swedenthing (a 1973 performance by the same band included inThe!!!!Beat video) where they’re out there in the middle ofMother Nature. You hit that lick and you don’t hear it comingback off the back wall to you. It’s a whole differentatmosphere. And in that little studio we were in, boy, itwas humming in there. It was really something.

On January 20, 1973, Freddie King and a tight quartet performed at a TVstudio in Dallas, Texas. “It was humming in there,” recalls director JimRowley. “Absolutely cooking.” King was 38 and enjoying what he called“the Fillmore circuit” in America as well as the adulation of throngs(including adoring rock stars) in Europe, especially England. This wasthe second time King had the brass ring firmly in hand, the first beingduring the early 1960s ‘dance party’ era of his success with Hide Away.Too soon it all ended with King’s 1976 death (he was only 42), but he leftus a vibrant musical legacy which includes concert performances likethis, a stunning example of a blues master coming to triumphant termswith 1970s African-American grooves and ‘playing funky.’

King’s daughter Wanda recalls: “My father was always contemp-orary, so it was no effort for him to get funky!” With his deep Texas bluesroots and Chicago blues apprenticeship always evident, King’s foundation

was forever the blues, but he was notabout to become an ‘oldies’ act

and made his blues a very real part of the music of the moment.

Tastefully intercut with the performance audio are brief

recollections by King of his career as he saw it in 1973,

adding insight into the man and his music.

Titles Include:Big Legged Woman

Ain't Nobody's BusinessLook On Yonder Wall

Ain't No SunshineBlues Band Shuffle

Have You EverLoved A Woman

Going Down & Hide Away

ISBN: 1-57940-952-0

Vestapol 13028

0 1 1 67 1 30289 8

Running Time: 58 minutes • ColorFront Cover Photo: Chuck Pulin/Star File

Back Cover Photo: Anton Joseph MikofskyNationally distributed by Rounder Records,One Camp Street, Cambridge, MA 02140

Representation to Music Stores byMel Bay Publications

® 2002 Vestapol ProductionsA division of Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop Inc.