13 is - hughesworldgeo.files.wordpress.com · When Arab armies conquered the region, they carried...

Transcript of 13 is - hughesworldgeo.files.wordpress.com · When Arab armies conquered the region, they carried...

Sugar Love – (A not so sweet story) By Rich Cohen, National Geographic

Bottom of the Drink

They had to go. The Coke machine, the snack

machine, the deep fryer. Hoisted and dragged

through the halls and out to the curb, they sat

with other trash beneath gray, forlorn skies

behind Kirkpatrick Elementary, one of a handful

of primary schools in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

That was seven years ago, when administrators

first recognized the magnitude of the problem.

Clarksdale, a storied delta town that gave us the

golden age of the Delta blues, its cotton fields

and flatlands rolling to the river, its Victorian

mansions still beautiful, is at the center of a colossal American health crisis. High rates of obesity, diabetes, high

blood pressure, heart disease: the legacy, some experts say, of sugar, a crop that brought the ancestors of most

Clarksdale residents to this hemisphere in chains. “We knew we had to do something,” Kirkpatrick principal

SuzAnne Walton told me.

Walton, Clarksdale born and bred, was leading me through the school, discussing ways the faculty is trying to help

students—baked instead of fried, fruit instead of candy—most of whom have two meals a day in the lunchroom. She

was wearing scrubs—standard Monday dress for teachers, to reinforce the school’s commitment to health and

wellness. The student body is 91 percent African American, 7 percent white, “and three Latinos”—the remaining 2

percent. “These kids eat what they’re given, and too often it’s the sweetest, cheapest foods: cakes, creams, candy. It

had to change. It was about the students,” she explained.

Take, for example, Nicholas Scurlock, who had recently begun his first year at Oakhurst Middle School. Nick, just

tall enough to ride the coaster at the bigger amusement parks, had been 135 pounds going into fifth grade. “He was

terrified of gym,” Principal Walton told me. “There was trouble running, trouble breathing—the kid had it all.”

“Of course, I’m not one to judge,” Walton added, laughing, slapping her thighs. “I’m a big woman myself.”

I met Nick in the lunchroom, where he sat beside his mother, Warkeyie Jones, a striking 38-year-old. Jones told me

she had changed her own eating habits to help herself and to serve as an example for Nick. “I used to snack on

sweets all day, ’cause I sit at a desk, and what else are you going to do? But I’ve switched to celery,” she told me.

“People say, ‘You’re doing it ’cause you’ve got a boyfriend.’ And I say, ‘No, I’m doing it ’cause I want to live and be

healthy.’”

Take a cup of water, add sugar to the brim, let it sit for five hours. When you return, you’ll see that the crystals have

settled on the bottom of the glass. Clarksdale, a big town in one of the fattest counties, in the fattest state, in the

fattest industrialized nation in the world, is the bottom of the American drink, where the sugar settles in the bodies

of kids like Nick Scurlock—the legacy of sweets in the shape of a boy.

Mosques of Marzipan

In the beginning, on the island of New Guinea, where sugarcane was domesticated some 10,000 years ago, people

picked cane and ate it raw, chewing a stem until the taste hit their tongue like a starburst. A kind of elixir, a cure for

every ailment, an answer for every mood, sugar featured prominently in ancient New Guinean myths. In one the first

man makes love to a stalk of cane, yielding the human race. At religious ceremonies priests sipped sugar water from

coconut shells, a beverage since replaced in sacred ceremonies with cans of Coke.

Sugar spread slowly from island to island, finally reaching the Asian mainland around 1000 B.C. By A.D. 500 it was

being processed into a powder in India and used as a medicine for headaches, stomach flutters, impotence. For years

sugar refinement remained a secret science, passed master to apprentice. By 600 the art had spread to Persia, where

rulers entertained guests with a plethora of sweets. When Arab armies conquered the region, they carried away the

knowledge and love of sugar. It was like throwing paint at a fan: first here, then there, sugar turning up wherever

Allah was worshipped. “Wherever they went, the Arabs brought with them sugar, the product and the technology of

its production,” writes Sidney Mintz in Sweetness and Power.“Sugar, we are told, followed the Koran.”

Muslim caliphs made a great show of sugar. Marzipan was the rage, ground almonds and sugar sculpted into

outlandish concoctions that demonstrated the wealth of the state. A 15th-century writer described an entire

marzipan mosque commissioned by a caliph. Marveled at, prayed in, devoured by the poor. The Arabs perfected

sugar refinement and turned it into an industry. The work was brutally difficult. The heat of the fields, the flash of

the scythes, the smoke of the boiling rooms, the crush of the mills. By 1500, with the demand for sugar surging, the

work was considered suitable only for the lowest of laborers. Many of the field hands were prisoners of war, eastern

Europeans captured when Muslim and Christian armies clashed.

Perhaps the first Europeans to fall in love with sugar were British and French crusaders who went east to wrest the

Holy Land from the infidel. They came home full of visions and stories and memories of sugar. As cane is not at its

most productive in temperate climes—it needs tropical, rain-drenched fields to flourish—the first European market

was built on a trickle of Muslim trade, and the sugar that reached the West was consumed only by the nobility, so

rare it was classified as a spice. But with the spread of the Ottoman Empire in the 1400s, trade with the East became

more difficult. To the Western elite who had fallen under sugar’s spell there were few options: deal with the small

southern European sugar manufacturers, defeat the Turk, or develop new sources of sugar.

In school they call it the age of exploration, the search for territories and islands that would send Europeans all

around the world. In reality it was, to no small degree, a hunt for fields where sugarcane would prosper. In 1425 the

Portuguese prince known as Henry the Navigator sent sugarcane to Madeira with an early group of colonists. The

crop soon made its way to other newly discovered Atlantic islands—the Cape Verde Islands, the Canaries. In 1493,

when Columbus set off on his second voyage to the New World, he too carried cane. Thus dawned the age of big

sugar, of Caribbean islands and slave plantations, leading, in time, to great smoky refineries on the outskirts of glass

cities, to mass consumption, fat kids, obese parents, and men in XXL tracksuits trundling along in electric carts.

Slaves to Sugar

Columbus planted the New World’s first sugarcane in Hispaniola, the site, not coincidentally, of the great slave

revolt a few hundred years later. Within decades mills marked the heights in Jamaica and Cuba, where rain forest

had been cleared and the native population eliminated by disease or war, or enslaved. The Portuguese created the

most effective model, making Brazil into an early boom colony, with more than 100,000 slaves churning out tons of

sugar.

As more cane was planted, the price of the product fell. As the price fell, demand increased. Economists call it a

virtuous cycle—not a phrase you would use if you happened to be on the wrong side of the equation. In the mid-17th

century sugar began to change from a luxury spice, classed with nutmeg and cardamom, to a staple, first for the

middle class, then for the poor.

By the 18th century the marriage of sugar and slavery was complete. Every few years a new island—Puerto Rico,

Trinidad—was colonized, cleared, and planted. When the natives died, the planters replaced them with African

slaves. After the crop was harvested and milled, it was piled in the holds of ships and carried to London, Amsterdam,

Paris, where it was traded for finished goods, which were brought to the west coast of Africa and traded for more

slaves. The bloody side of this “triangular trade,” during which millions of Africans died, was known as the Middle

Passage. Until the slave trade was banned in Britain in 1807, more than 11 million Africans were shipped to the New

World—more than half ending up on sugar plantations. According to Trinidadian politician and historian Eric

Williams, “Slavery was not born of racism; rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.” Africans, in other words,

were not enslaved because they were seen as inferior; they were seen as inferior to justify the enslavement required

for the prosperity of the early sugar trade.

The original British sugar island was Barbados. Deserted when a British captain found it on May 14, 1625, the island

was soon filled with grinding mills, plantation houses, and shanties. Tobacco and cotton were grown in the early

years, but cane quickly overtook the island, as it did wherever it was planted in the Caribbean. Within a century the

fields were depleted, the water table sapped. By then the most ambitious planters had left Barbados in search of the

next island to exploit. By 1720 Jamaica had captured the sugar crown.

For an African, life on these islands was hell. Throughout the Caribbean millions died in the fields and pressing

houses or while trying to escape. Gradually the sin of the trade began to be felt in Europe. Reformers preached

abolition; housewives boycotted slave-grown cane. In Sugar: A Bittersweet History Elizabeth Abbott quotes Quaker

leader William Fox, who told a crowd that for every pound of sugar, “we may be considered as consuming two

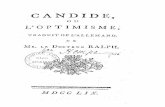

ounces of human flesh.” A slave in Voltaire’s Candide, missing both a hand and a leg, explains his mutilation: “When

we work in the sugar mills and we catch our finger in the millstone, they cut off our hand; when we try to run away,

they cut off a leg; both things have happened to me. It is at this price that you eat sugar in Europe.”

And yet there was no stopping the boom. Sugar was the oil of its day. The more you tasted, the more you wanted. In

1700 the average Englishman consumed 4 pounds a year. In 1800 the common man ate 18 pounds of sugar. In 1870

that same sweet-toothed bloke was eating 47 pounds annually. Was he satisfied? Of course not! By 1900 he was up

to 100 pounds a year. In that span of 30 years, world production of cane and beet sugar exploded from 2.8 million

tons a year to 13 million plus. Today the average American consumes 77 pounds of added sugar annually, or more

than 22 teaspoons of added sugar a day.

If you go to Barbados today, you can see the legacies of sugar: the ruined mills, their wooden blades turning in the

wind, marking time; the faded mansions; the roads that rise and fall but never lose sight of the sea; the hotels where

the tourists are filled with jam and rum; and those few factories where the cane is still heaved into the presses, and

the raw sugar, sticky sweet, is sent down the chutes. Standing in a refinery, as men in hard hats rushed around me, I

read a handwritten sign: a prayer beseeching the Lord to grant them the wisdom, protection, and strength to bring

in the crop.

The Healthy Chef

Though just 11, Nick Scurlock is a perfect stand-in for the average American in the age of sugar. Hyperefficient at

turning to fat the fructose the adman and candy clerk pump into his liver at a low, low price. One hundred thirty-five

pounds in fifth grade, in love with the sweet poison endangering his life. Sitting in the lunchroom, he smiled and

asked, “Why are the good things so bad for you?”

But this story is less about temptation than about power. At its best, the school can help kids make better decisions.

A few years ago Pop-Tarts and pizza were served at Kirkpatrick. Now, across the district, menus have improved. The

school has a garden that grows food for the community, a walking track for students and the public, and a new

playground.

In a sense the struggle in Clarksdale is just another front in the continuing battle between the sugar barons and the

cane cutters. “It’s a tragedy that hits the poor much harder than it does the rich,” Johnson told me. “If you’re wealthy

and want to have fun, you go on vacation, travel to Hawaii, treat yourself to things. But if you’re poor and want to

celebrate, you go down to the corner and buy an ice-cream cake.”

When I asked Nick what he wanted to be when he grew up, he said, “A chef.” Then he thought a moment, looked at

his mom, and corrected himself. “A healthy chef,” he said.

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2013/08/sugar/cohen-text

For Inca Road Builders, Extreme Terrain Was No Obstacle

AUGUST 29, 2015 6:49 AM ET

JASMINE GARSD

The Inca were innovators in agriculture as well as engineering. Terracing like this, on a steep hillside in Peru's Colca Canyon, helped them grow

food. One of history's greatest engineering feats is one you rarely hear of. It's the Inca Road, parts of which still exist today across much of South America.

Back in the day — more than 500 years ago — commoners like me wouldn't have been able to walk on the Inca Road, known as Qhapaq Ñan in the Quechua language spoken by the Inca, without official permission. Fortunately, I have Peruvian archaeologist Ramiro

Matos by my side. He is the lead curator of an exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian called "The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire."

That's "Inka" with a K, as it's spelled in Quechua. And today, we're taking a virtual journey down what was once more than 20,000 miles of road traversing some of the world's most challenging terrain — mountains, forests and deserts.

The Inca road began at the center of the Inca universe:Cusco, a city in the Peruvian Andes, said to be built in the shape of a crouching puma. It actually was not a single road but a network of royal roads, an instrument of power designed for military transport, religious pilgrimages and to move supplies. "As far as the road stretches, the empire stretches," says Ramos.

The road spanned modern-day Argentina, Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and Colombia. The museum exhibition's photographs of it are vertigo-inducing: Massive pathways wind up tall mountains and touch the clouds; sturdy staircases unwind into lush, green valleys, as if the brutal nature of the landscape had been just a small inconvenience to work around.

"The highest part of the road crosses from Argentina to Chile, nearly 20,000 feet high," Matos says.

How did they build this? "Local experience."

The Inca were master engineers. But like most conquerors, they also tapped local experts. The exhibition highlights a long

bridge made of woven plant fibers, still in use today. "There's an inventory of over 100 bridges in all of the empire — this is one of the few which remain. It's made with icchu or puna grass," Matos says. The Inca Empire only lasted about a century. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived, that intricate road made it easier for them to move around and access precious mines that the Incas themselves had been exploiting.

Today, most of the old road has been destroyed — both by the Spanish conquest and by modern highways. Some parts remain and are still in use.

Schoolchildren around the world learn about the ancient Roman roads and the Great Wall of China — but most people have heard little about the great Inca Road. Kevin Gover, the director of the National Museum of the American Indian, says the road is largely forgotten because it just doesn't fit into a typical Western narrative. "Indians play one of two roles in that narrative," he says. "They are either the opponents of civilization or they are literally part of the nature that was there to be settled and conquered. We're not taught that some of these were very advanced civilizations, because that means this wasn't a wilderness. And that means somebody had to be displaced. And it wasn't necessarily a noble endeavor."

That's why the museum created the exhibit, which is on display till 2018.

The great Inca Road reminds us that, once upon a time, all roads led not to Rome — but to Cusco, Peru.

The Last Incan Suspension Bridge Is Made Entirely of Grass and Woven by Hand

By Atlas Obscura

The Incas never invented the wheel, never figured out the arch, and never discovered iron. But they were masters of fiber. They built ships out of fiber (you can still find reed boats sailing on Lake Titicaca). They made armor out of fiber (pound for pound, it was stronger than the armor worn by the Conquistadors). Their greatest weapon, the sling, was woven from fibers, and was powerful enough to split a steel sword. They even communicated in fiber, developing a language of knotted strings known as quipo, which has yet to be decoded. So when it came to solving a problem like how to get people and goods across the steep gorges of the

Andes, it was only natural that they would think about the problem in terms of fiber.

Five centuries ago, the Andes were strung with suspension bridges. By some estimates there were as many as 200 of them, braided from nothing more than twisted mountain grass and other vegetation, with cables sometimes as thick as a human torso. Three hundred years before Europe saw its first suspension bridge, the Incas were spanning longer distances and deeper gorges than anything that the best European engineers, working with stone, were capable of.

Over the centuries, the empire’s grass bridges gradually gave way, and were replaced with more conventional works of modern engineering. The most famous Incan bridge—the 148-footer immortalized by Thornton Wilder in The Bridge of San Luis Rey—lasted until the 19th century, but it too eventually collapsed. Today, there is just one Incan grass bridge left, the keshwa chaca, a sagging 90-foot span that stretches between two sides of a steep gorge, near Huinchiri, Peru. According to locals, it has been there for at least 500 years.

Here in the desolate, 2-mile-high Andean altiplano, little else grows besides ichu, a tall needly grass that covers the mountainsides, feeds the llamas, and is the raw material from which the keshwa chaca is constructed. The walkway of the keshwa chaca consists of four parallel ropes with a mat of small twigs laid across, anchored at both ends by a platform of larger rocks. Two other thick ropes acts as armrails, and are connected to the walkway with a cobweb of smaller cord. Despite its seemingly fragile materials, modern load testing has found that in peak condition, the keshwa chaca can support the weight of 56 people spread our evenly across its length.

In 1968, the government built a steel truss bridge just a few hundred yards upstream from the kewsha chaca. Though most locals now use it instead of the grass bridge to cross the valley, the tradition of rebuilding the keshwa chaca each year has not abated. Each June, it is renewed in an elaborate three-day ceremony. Each household from the four surrounding towns, is responsible for bringing 90 feet of braided grass cord. Construction takes place under the supervision of the all important bridge keeper, or chacacamayoc. The old bridge is then cut down and thrown into the river. Because it has to be willfully, ritually regenerated each year, the keshwa chaca’s ownership passes from generation to generation as a bridge not only across space, but also time.

Mexico City’s Aztec Past Reaches Out to Present By ELISABETH MALKIN and SOFIA CASTELLO Y TICKELL September 2, 2012

MEXICO CITY — The skeleton is that of a young woman, perhaps an Aztec noble, found intact and buried in

the empire’s most sacred spot more than 500 years ago. Almost 2,000 human bones were heaped around her,

and she is a mystery.

There are other discoveries yet to be deciphered from the latest excavation site at the heart of this vast

metropolis, where the Aztecs built their great temple and the Spanish conquerors laid the foundation of their

new empire.

Before announcing the

finding of the unusual burial

site and the remains of what

may be a sacred tree last

month, archaeologists had

also recently revealed a giant

round stuccoed platform

decorated with serpents’

heads and a floor carved in

relief that appears to show a

holy war.

Mexico City might be one of the world’s classic megacities, an ever-expanding jumble of traffic, commerce,

grand public spaces, leafy suburbs and cramped slums. But it is also an archaeological wonder, and more than

three decades after a chance discovery set off a systematic exploration of the Aztecs’ ceremonial spaces,

surprises are still being uncovered in the city’s superimposed layers.

“It’s a living city that has been transforming since the pre-Hispanic epoch,” said Raúl Barrera, who leads the

exploration of the city’s center for the National Institute of Anthropology and History here.

“The Mexicas themselves dismantled their temples,” to build over them, he explained, using the Aztecs’ name

for themselves. “The Spanish constructed the cathedral, their houses, with the same stones from the pre-

Hispanic temples. What we have found are the remains of that whole process.”

Perhaps nowhere else in the world is the evidence of a rupture between civilizations as dramatic as in Mexico

City’s giant central square, known as the Zócalo, where the ruin of the Aztecs’ Templo Mayor abuts the

ponderous cathedral the Spanish erected to declare their spiritual dominance over the conquered.

“I think the ideological war was more difficult for the Spanish than armed warfare,” said Eduardo Matos

Moctezuma, the archaeologist who first led the excavation of the Templo Mayor.

There are other, older places in the world where ruins rise from traffic-clogged streets, where foreign invaders

ended empires. But it is different here, academics say.

“They blew the top of it off; they didn’t do that to the Colosseum,” said Davíd Carrasco, a historian of religions

at Harvard University who has written on the Aztecs and the excavations at the Templo Mayor. “In Rome, the

ancient Roman city stands alongside the medieval and the modern city.”

A Spanish chronicler of the conquest, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote that “of all these wonders” of the Aztec

capital, Tenochtitlan, “all is overthrown and lost, nothing left standing.”

Since 1790, though, when construction work to pave the Zócalo unearthed the first giant Aztec carvings,

Tenochtitlan has been giving up its secrets. Archaeologists began exploring the Templo Mayor a century ago,

but the discovery of a giant monolith depicting the decapitated, dismembered Aztec moon goddess

Coyolxauhqui in 1978 led to a full-scale excavation that continues today.

In the first five years, archaeologists had uncovered large parts of the temple that lay underneath a structure

razed by the Spanish after the 1521 conquest. Past Aztec emperors had built new temples over earlier ones,

which unwittingly spared the older structures.

The archaeological project “wasn’t just that we were going to find an enormous temple,” Mr. Matos said. “It

was what it meant within Aztec society. That building was very important because for them it was the center of

the universe.”

There is still much more to uncover around the Templo Mayor. The 16th-century Franciscan Friar Bernardino

de Sahagún left a record of what Mr. Matos calls the Aztecs’ sacred precinct of temples and palaces, now a

densely packed square about seven blocks on each side.

The Sahagún account, compiled from Aztecs’ recollections of their lost city, has proved strikingly accurate. Of

the 78 structures he described, archaeologists have found vestiges of more than half.

During the most recent excavation, underneath a small plaza wedged between the Templo Mayor and the

cathedral, Mr. Barrera had been looking for the round ceremonial platform because it had been described in the

Sahagún record.

Much of what the friar and other witnesses chronicled now lies as deep as 25 feet underground. To get there,

Mr. Barrera’s team must first navigate the electricity lines and water mains that are the guts of the modern city

and then travel down through a colonial layer, which yields its own set of artifacts.

“It is like a book that we are trying to read from the surface to the deepest point,” he said.

But despite the guidance from historical records, Mexico City’s archaeologists cannot dig anywhere they please.

Part of the sacred precinct is now a raucous medley of the mundane. The street vendors hawking pirated

Chinese-made toys and English-language lesson CDs from crumbling facades are merely the loudest. To

excavate under the area’s hotels, diners, cheap clothing stands and used bookstores would entail fraught

negotiation.

Along the quieter blocks of the precinct, handsome colonial structures are now museums and government

buildings, themselves historical landmarks.

Archaeologists believe that the Calmécac, a school for Aztec nobles, extends under the courtyards of Mexico’s

Education Ministry building. For now, the only part of the Calmécac that has been excavated are several walls

and sculptures on display under a building housing the Spanish cultural center, discovered when it was

remodeled.

Still, in a strange sort of payback, the ruins themselves sometimes make it possible for the archaeologists to

enter private property and begin digging.

Since the 16th century, the city has pumped water from deep wells to satisfy its thirst, causing the clays beneath

the surface to sink as water is sucked from them, rather like a dry sponge.

But the buildings settle unevenly, buckling over the solid stone Aztec ruins below, lending many of the sacred

precinct’s streets a swaying, drunken air.

As cracks open and the buildings tilt, many of them need restoration, which by law allows archaeologists from

the anthropology and history institute to keep watch. If historic remains are found, the owner must foot the bill

to restore them.

When the cathedral needed to be rescued in the 1990s, engineers dug 30 shafts to stabilize the structure and Mr.

Matos and his team descended as far as 65 feet to see what was underneath.

“It’s the vengeance of the gods,” he said. “The cathedral is falling and the monuments to the ancient gods are

what’s causing it to fall.”

Among other things, the archaeologists found the remains of Tenochtitlan’s ball court, where Aztecs played

a ritual ballgame common across ancient Mesoamerica. It remains sealed deep under the cathedral’s apse and

the cobblestone street to its north.

“That whole part of the city is like a graveyard of people and of significant cultural objects,” Mr. Carrasco said.

“And they awaken every time Mexico reaches for its future.”

THE BRUTAL AND BLOODY HISTORY OF THE MESOAMERICAN BALL GAME, WHERE SOMETIMES LOSS WAS DEATH

BY MONICA PETRUS / 09 JAN 2014

A ball court in Mexico (photograph by Dennis Jarvis)

The Olmecs started it, the Maya tweaked it, and the Aztecs nailed it. The Mesoamerican Ballgame, played with a

solid rubber ball — weighing at around 10 pounds — and teams of one to four people, makes a regular appearance

throughout Pre-Columbian history. Though added later, stone ball courts have been found from Arizona to Nicaragua.

Though the exact rules of the game aren't known, it is generally believed that the game was played more or less like

today's volleyball (net‐less) or racquetball. Players wore helmets, pads and thick protective yokes around their mid‐section

and kept the ball in play by hitting it off their hips.

The Mesoamerican ball game makes its first appearance among the Olmec around 1500 BC in the central Gulf

Coast of Mexico, an area known at the time for latex production. Many balls have been discovered in the region as part of

burials and as ritual offerings at shrines, suggesting the balls and other ballgame accoutrements were a sign of status or

wealth. In fact, this idea has been reinforced by the evidence of ball courts being found near chief’s homes in Olmec sites.

The game the Olmecs played was associated with prestige and social standing, and only the wealthy and therefore upper

class could afford to put on a game. The giant stone heads found in the region also depict chiefs wearing the ball playing

helmet.

Olmec head in the Parque Museo La Venta in Mexico (photograph bySteven Bridger)

A ceramic depiction of a ball game

in the Museo Rufino Tamayo of

Oaxaca (photograph by Thomas

Aleto)

Carving of a human sacrifice after a ball game in Veracruz, Mexico (photograph by Thomas Aleto)

The game continued to be played throughout Mesoamerica when it was adopted by the Maya, who added their own

special twist. Humans and the lords of the underworld battled it out by playing the game, according to the creation story

the known as the Popol Vuh. In this way, the ball court was a portal to Xibalba — the Mayan underworld. The Maya used

the game as a stand‐in for warfare, settling territory disputes and hereditary issues, and to foretell the future. Captives of

wars were forced to play (undoubtedly rigged) games that resulted in their sacrifice when they lost.

Sacrificed ball player in the Anthropolgy Museum of Xalapa, Mexico

(photograph by Maurice Marcellin)

Two ball players on a carving in Guatemala (photograph by Simon Burchell)

The Aztecs continued this proud tradition of loser‐lose‐all, as many vases and sculptures depict the inevitable decapitation

of the losing team. There are even some depictions of ball players playing with the heads of the losers in place of a ball.

Whether this actually occurred is up to artistic speculation. The Spanish who observed the game reported horrendous

injuries to those who played it — deep bruising requiring lancing, broken bones, and even death when a player was hit in

the head or by an unprotected bit by the heavy ball.

A ball court in Oaxaca (photograph by Matt Barnett)

Shadow of a stone hole at a ball court (photograph by Erik Bremer)

The Great Ball Court at Chichén-Itzá in Mexico (photograph by Daryl Mitchell)

There are many of these fine ball courts one can visit today. The great ball court at Chichen Itza, built around 800 AD, is

the largest and best preserved yet found. The Maya added the stone ring for bonus point opportunities, but putting the ball

through the hoop was a very rare event. In fact, mayan ball courts can be explored at just about every archaeological site

including: Palenque, Yaxchilan, Tikal, Uxmal, Ek Balam, Copan, and Calakmul. And while you can't do much playing

now at these historic sites, a slightly less gruesome version of the game called Ulama still survives is played in Mexico

today.

An ulama player (photograph by Manuel Aguilar)

Dark-Skinned Or Black? How Afro-Brazilians Are Forging A Collective Identity

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO FacebookTwitterInstagram

Sisters Francine and Fernanda Gravina have German,

Italian, African and indigenous ancestry.

Lourdes Garcia-Navarro/NPR

If you want to get a sense of how complex racial

identity is in Brazil, you should meet sisters Francine

and Fernanda Gravina. Both have the same mother and

father. Francine, 28, is blond with green eyes and

white skin. She wouldn't look out of place in Iceland.

But Fernanda, 23, has milk chocolate skin with coffee

colored eyes and hair. Francine describes herself as

white, whereas Fernanda says she's morena, or brown-

skinned.

"We'd always get questions like, 'How can you be so

dark skinned and she's so fair?'" Fernanda says. In fact,

the sisters have German, Italian, African and

indigenous ancestry. But in Brazil, Fernanda explains,

people describe themselves by color, not race, since nearly everyone here is mixed.

All of that is to say, collecting demographic information in Brazil has been really tricky. The latest census, taken in 2010, found

for the first time that Brazil has the most people of African descent outside Africa. No, this doesn't mean that Afro-Brazilian

population suddenly, dramatically increased. Rather, the new figures reflect changing attitudes about race and skin color in

Brazil.

Racial mixing came about early in Brazil's history. Brazil imported more enslaved people than anywhere else in the Americas

— some four million — and slavery lasted longer there than anywhere else in the region. The white Portuguese colonizers were

encouraged to "mingle" with the locals. Plainly speaking, this meant that they raped many African and indigenous women.

The result is a vast mixed-race population, which has been added to over the years with successive migrations from Japan and

Europe.

We should see the history of Brazil as a history of racial inequality

Rosana Heringer, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro

Unlike the U.S., where slavery was followed by legal segregation, Brazil never had a formal system of apartheid, says Rosana

Heringer, a sociologist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro who studies race and the African diaspora. Still, there is a

color hierarchy in Brazil, Heringer says. Consistent data shows that darker Brazilians are poorer, and they're more likely to be

killed and live in slums, called favelas .

"We should see the history of Brazil as a history of racial inequality," Heringer says — and that's a fairly new idea. For a long

time, Brazilians have believed in what's been called "the myth of racial democracy," she explains. Part of that myth-building

was a controversial survey that the government conducted the 1970's. It asked people to describe their skin color, and the

answers varied a lot. All together, respondents used at least 134 different terms.

The descriptions ran the gamut from the fanciful to the almost forensically descriptive: "sunburned white," "white with brown

spots" and "white like a meringue." Some characterized their skin tone as cinnamon or burnished rose, toffee or cashew tan.

Someone even used the phrase "burro (donkey) running away."

"It created a fable, every time more exaggerated, that supported the idea that you couldn't take a serious look at race in Brazil,"

says Jose Luis Petruccelli, a former lead researcher for 20 years at the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, which

carried out the survey.

The institute also organizes the national census every decade. These days there are five formal color categories in the census:

indigenous, yellow, white, pardo (or brown) and preto, or dark-skinned, Petruccelli says. The word black doesn't appear

anywhere in the list.

"There is a totally different system here than in the U.S., where one drop of black blood makes you black independent of

appearance," Petruccelli says. In Brazil, it's about how you'd like to classify yourself, and how others see you. The problem, he

says, is that Afro-Brazilians have no sense of collective identity, which makes it difficult to address the very real problem of

racism and racial inequality in the country.

But lately, that's starting to change, and the black pride movement in Brazil is growing. On a recent morning at the beach in Rio

de Janeiro, a march celebrating black women in Brazil started with with dancing and singing. One of the demonstrators, Jurema

Werneck, who works at Criolla, an advocacy group for black women, says the goal of the march is to show that Brazil is a black

nation, largely populated black and African Brazilians. "We need to fight racism and not to hide it," Werneck says.

She's been participating in the black pride movement for over 15 years. And it seems to be working, she says, because the

number of people self identifying as pardo or pretosurged in the latest census.

And more importantly, lawmakers are beginning to pay more attention to issues of inequality. Brazil now has an affirmative

action program for higher education. Before the program launched, only seven percent of Afro-Brazilians went to college. Now

it's about 15 percent, and the numbers are growing.

Werneck says the black pride movement is also lobbying to change the next census in 2020 to include the word

black. Pardo and preto, she says, are euphemisms. Afro-Brazilians should take a cue from African-Americans, she says, and

broadcast to society that they're black and proud.