· Web viewIn an acrostic poem, the first letters of each line combine to make a word or words,...

Transcript of · Web viewIn an acrostic poem, the first letters of each line combine to make a word or words,...

Scottish Poetry Library & National Museums of Scotland

Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack March 2013

1National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

This pack contains practical ideas and tips for pre-and post-workshop activity for the age-ranges P6-S2 and S3-S6

If you would like to book a Ghosts of War workshop for November 2013, please contact the Learning and Programmes Administrator, National Museums Scotland, 0131 247 4206.

Contents

Section 1 – The Workshop 1.1 History of the Project

1.1.1 20031.1.2 2004–2012

1.2 The Workshop Schedule & Descriptor

Section 2 – Pre-workshop Activities2.1 Reading & Talking Task2.2 Research Task – Personal Histories2.3 Writing Task – Mesostic Poems2.4 History Task

Section 3 – Post-workshop Activities3.1 Writing Review3.2 Editing Tips3.3 Extension Writing Tasks

3.3.1 For P6–S2 War Memorial3.3.2 For S3–S6 A Humument3.3.3 For S3–S6 A Found Poem

3.4 More poems to Read Together

2National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

Section 1 - The Workshop

1.1 History of the Project

1.1.1 2003

The first Ghosts of War poetry workshops were offered to P6-7 primary school pupils in November 2003, and were allied to a photographic exhibition, Terrain: Landscapes of the Great War by Peter Cattrell, at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. So affecting was the response of children to this exhibition, we felt we must continue to provide a focus for remembrance through art and poetry, for young people.

The photographs in Terrain showed battlefields of the First World War, in which several of the artist’s forebears had fought, and these grave and reticent images of trenches and craters, softened by mantles of thick grass, evoked in a remarkably powerful way for the children, the lives and deaths of the hundreds of thousands of British and German troops who perished there.

In revisiting the pastoral landscape tradition of painting, Cattrell’s photography, whilst it engaged with the calamities of the Great War, presented nature as a force of restoration and of healing. We were reminded of Carl Sandberg’s powerful poem, ‘Grass’, and of the restorative power of the art of poetry itself, and so the idea for an annual series of Armistice workshops took root.

The title of one of the poems, displayed as part of the exhibition, Ewart Mackintosh’s Ghosts of War, ignited children’s imaginations, and so we have them to thank for the title of our programme, which aims to remind children that we can remember those we never knew, and their sacrifice.

1.1.2 2004–2012

As Terrain was a temporary exhibition, we were pressed to find another venue for November 2004; one which also offered strong stimulus for affective learning. It was not long before we embarked on a visit to the National War Memorial and Museum, where we discovered unparalleled riches for teaching and learning about war and remembrance, past and present.

Our cross-curricular workshop programme is now in its tenth year and takes place annually in the weeks surrounding Armistice Day, supported and sponsored by our long-term partners, the National Museums of Scotland/Scottish National War Museum.

The whole-day sessions focus on the First and Second World Wars, and represent a unique opportunity to expand young people’s awareness of the human tragedy of all war, and to allow them to bear witness to the sacrifice of individuals, through poetry, in their own unique and personal way.

3National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

Pupils record personal responses to a range of primary source handling objects, and to some of the powerful and moving exhibits in the Scottish National War Museum, as well as participating in an Act of Remembrance at the Scottish National War Memorial.

Edinburgh poet Ken Cockburn then helps pupils to synthesise their experience and thoughts, shaping language to create their very own poems of war, peace and remembrance.

2012: In a world where wars continue to play out, it is even more important to remember; we continue to encourage young people to regard the experiences we offer, and approach the act of writing their own poetry, as personal, restorative acts of Remembrance.

A truly enriching learning experience – for me as well as the children! Primary teacher 2011

A superb workshop. Loved the way it foregrounded the human issues often back-grounded in text (and my teaching!). My seniors thought it was great. Secondary Higher History teacher 2010

It was a valuable chance to view a vast array of resources I’d no idea existed… Primary HT 2009

First class in every way; I really admired your expertise and knowledge. A very positive learning experience for the children. Primary teacher, 2008

4National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

1.2 The Workshop Schedule & Descriptor

09.50 Arrival at Castle EsplanadeWe welcome and introduce the workshop, our themes, aims and to the day’s activities. We make it clear that these activities are designed specifically to mimic the kind of research a writer might undertake to inform and inspire – that the act of writing will benefit from direct and authentic experience and observation, and that the act of writing will, in itself, constitute an act of remembrance.

10.10 Tour and Act of Remembrance at Scottish National War MemorialWe talk a little about the history, design, contents and significance of the memorial and then enter to explore the building. We focus pupils on the ways in which war and remembrance are evoked, including stained glass, statuary, bas relief, frieze, inscription, insignia and books. We discuss these with them and then allow them time to explore on their own, observing and collecting thoughts, ideas and reactions. We end our visit with a poem, a minute’s silence, and poppies.

10.50 Education Room: Worksheets & Memorial NotesWe distribute our Ghosts of War worksheets and encourage students to recall and record their responses and sensory observations from the memorial

11.05 Break

11.20 Handling Session – presentationWe introduce pupils to some primary source artefacts, speak about the context in which they were owned and used, and invite the pupils themselves to handle, explore and imagine them, as yet another source of inspiration for their poems. Pupils select a single object and finish this session by writing detailed notes.

12.00 Museum visit Our final stimulus takes us to the galleries of the National War Museum where, after a demonstration of ‘how to look’ at vitrines, pupils have the opportunity again to browse and take inspiration from a single item and exercise a range of skills in reading, interpreting and imagining in order to remember its owner or user.

12.30 Lunch

13.00 Poetry workshopKen Cockburn works with pupils to help them convert their notes, observations, thoughts and feelings into remembrance poems.

14.00 Read aloud session & questions

14.15 Finish

Section 2 – Pre-workshop Activities

5National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

2.1 Reading & Talking Task

Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004), ‘Encounter’

Link to the poem here: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1980/milosz-poems-3-e.html

We read this poem to mark the beginning of our silence in the National War Memorial. It is dated ‘Wilno*, 1936’, but was first published in book form in 1945, at the end of the Second World War; so what was written as a personal elegy, probably based on a childhood memory, becomes an elegy for the death of many people, known and unknown. The poem is an invitation to imagine the dead when they were living in all their ordinariness, and to think about what it means that we, the living, remember them at all. * ‘Wilno’ is Vilnius, then as now the capital of Lithuania.

For P6–S2

Read the poem aloud. Read it in different ways:

quickly and slowlyindividually and chorallybecoming louder as you read, or becoming quieterfeaturing a male voice(s) and/or a female voice(s)using techniques like repetition or echo or vocal sound effects

Which do you think is the best way to read the poem? Why?

The poem is in two parts: one happened “long ago”, and the other “today”.Which lines of the poem took place “long ago”?Which lines of the poem are taking place “today”?

Look at some of the words and phrases used in the poem.What sort of journey might involve “riding through frozen fields in a wagon at dawn”?In line 2, what do you think the “red wing” is?What “encounter” does the title refer to?

For S3–S6

As above, but also consider these questions:

What do we learn about the “I” of the poem?The poem is about death and loss, but the poet feels “wonder” rather than “sorrow”. Why do you think this might be?Lines 7-8 begin like a question, but don’t end with a question mark. Why do you think the poet has decided not to use a question mark?Line 7 begins, “O my love”. Why do you think the poet chooses to address “my love” at this point in the poem? How would the poem be different if these words were omitted?

6National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

Try to think of an ‘encounter’ moment of your own about which you could write a short poem. Try to remember a simple event that you experienced or witnessed, perhaps in childhood, that has stayed in your memory, and which now that you are older you understand differently – perhaps seeing in it a special significance, deeper meaning or poignancy.

2.2 Research Task – Personal Histories

This task should be suitable for P6–S6, though the type of questions and amount of information gathered will vary as pupils become older.

Investigate the life of a family-member or forebear during wartime.

Perhaps you have a grandfather who was in the forces, or a grandmother who worked in the Land Army. Perhaps someone had to leave their home because of fighting, or perhaps they experienced war simply as a civilian.

Find out as much as possible about this personfacts – dates, places and journeysstories – events and experiences, which might be funny or scaryresponses – how they felt about what was happening

If you cannot find out about someone’s life during wartime, ask someone in your family what they remember about recent wars and conflicts, from the news, or from speaking to people who were more directly involved. These might include the

‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland (1969–1998)Falkland Islands (1982)First Gulf War (1991)Yugoslav wars (1992-95)invasion and occupation of Afghanistan (2001–date)invasion and occupation of Iraq (2003–2011)

Be aware that your questions may touch on sensitive matters, which people may not wish to talk about in detail.

7National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

2.3 Writing Task – Mesostic poems

Again, this task should be suitable for P6–S6, though the poem’s vocabulary and syntax can become more complex as pupils become older.

Write a mesostic poem, using what you have found out as part of your Research Task (at 2.2 above).

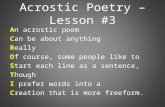

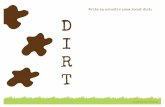

In an acrostic poem, the first letters of each line combine to make a word or words, usually the subject of the poem. In a mesostic poem, the letters which form the name of the subject can be read vertically down the centre of the page, forming the stem-word, as for example in this poem by Alec Finlay about A.S. Neill:

climbi N gtr E es Is a L ways a L lowed

Use the name of the person you researched as your stem-word. Drawing on your research, make a list of words about this person, as many as you can. At this stage don’t think too much about the letters the words contain – even if you can’t use them in your mesostic, they will help you think about the person you’re writing about.

You can use factsinformationdescriptionsfeelingsquestions

See which of your words contain letters that match those of your ‘stem’ word. Do these words – or the ones which don’t match – suggest others you could use?

How can you fit these together? A mesostic poem can be a short phrase or sentence, or it can simply be a list. Try out some combinations until you find one you like.

2.4 History Task

Ask your family about an object from the past – ideally something linked to wartime, but that’s not absolutely necessary – that has significance in terms of the life of the person who originally owned it. Bring it into school and talk about it to the class.

For P6–S2

8National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

Write down the name of your chosen object.Write down some adjectives that describe it. Think about its size, shape, feel touch, smell, colour, patterning, and so on.What is or was it used for?Who do you associate with it - whose is or was it? What places do you associate with it? Where did it come from?Are there any stories you can tell about it?If you could ask it one question, what would it be?

Read through your notes, and note down any other ideas you have.

For S3–S6

As above, but also think about your object as a piece of primary source material.

What does the object tell us about the time from which it comes? What does the object tell us about the person who owned it? How do we ‘read’ objects? Can they be misleading?

Section 3 – post-workshop activities

3.1 Writing Review

For P6–S2

Read through the poem you wrote at the Scottish National War Museum. See if there is anything you would like to change or add to it.

Working in pairs (or threes), exchange poems with your partner(s).

ReadingRead through your partner’s poem, and make sure you can read each word.Read your partner’s poem aloud, two or three times. Note any sections which you stumble over, and think about why this might be – to do with the rhythm, or sound, or meaning of the words?Offer three positives (things you like about the poem), two negatives (things you dislike about the poem) and one piece of advice to your partner about their poem.

Listening Listen to your own poem being read aloud.Which sections do you think work well, and which don’t?Do you agree with your partner’s positives, negatives and advice? Why?

For S3–S6

As well as doing the exercise above, answer these questions about your poem.9

National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

How does your finished poem relate to your experience of visiting the Memorial and Museum?Did the structure you were given help you or hinder you? Why?Describe the differences between your own and another person’s poem. Think about vocabulary, sentence structure, syntax, rhythm and metre, as well as content.To what extent is the poem you’ve written personal to you? (You should get a better idea of this after comparing it with other poems.)Can you think of another way of writing about your experiences at the Memorial and Museum?

3.2 Editing Tips

This is a set of tips for teachers to assist pupils to edit the poems written during their Ghosts of War day.

Editing a poem is in many ways like editing prose. Your main aim is to eliminate any errors you have made, to improve on words and passages that aren’t quite as good as they could be, and to work to make the poem hold together as a single unit.

Be specific in your use of vocabulary.

Examine your word choices. Sharpen action words and find unique descriptive words. Strive to avoid words that are markedly ‘poetic’, grandiose or obscure but equally, don't resort to bland overstatement. Avoid clichés, stock phrases, vague descriptions and words that are outdated or overly-formal.

So, for example

not ‘people’ but ‘soldiers’, ‘bridge-builders’, ‘airmen’, and so onnot ‘bird’ but ‘’crow’, ‘robin’, ‘buzzard’, and so on not ‘interesting’ but ‘colourful’, ‘massive’, ‘difficult’, and so on not ‘went’ but ‘walked’, ‘strolled’, ‘hurried’, etc.not ‘red’ but ‘berry-red’, not ‘white’ but ‘surgical white’

and avoid

amazingfantasticawesomeincrediblebrillianthorrificterrifying

10National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

Don’t overlook detail. Small, perhaps seemingly insignificant, details can bring a poem to life, so try to write about things you actually observed and experienced on the day, such as

sensory memoriesthings overheardthings that surprised or even shocked you

Rather than stating the feeling, try to demonstrate it through language and word-choice.

Instead of ‘I felt so sad’, find an image that expresses a mood of sadness, such as

a grey, overcast sky in the stained glassthe sound of a crow cawinga named object in the museum, such as a jacket with a bullet hole through it

Instead of ‘I felt so happy’, find an image that expresses a mood of happiness, such as

the sun appearing from behind a cloudthe sound of music from a passing car, or an open windowa named object in the museum, such as a photo of someone smiling

Avoid big rhetorical questions, such as

why did so many have to die so young?was their sacrifice in vain?why have we never learned from the terrible wars of the past?

Instead, use what you’ve learned, so perhaps

How did Tommy Atkins die, on a bitter winter day on the Somme?What would he tell us, Tam Young, grocer’s boy, far from home?The nurse’s uniform has too tiny a waist; how could she bear the work’s weight?

– and think of some answers!

Think carefully about adjectives and adverbs. Sometimes they help to describe something, and sometimes they just get in the way.

Try taking out all the adjectives and adverbs in your poem.Does the poem work better now, or is it confusing?If it is, add back some adjectives and adverbs, but only if they’re necessary!

11National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

How does the poem look on the page? Think about any patterns you’re using in your poem.

These might include rhyme, alliteration, repetitions, and so on. Sometimes a poem works better when it has regular patterns, and sometimes it needs to be freed from them, to be able to breathe. Often repetitions are as or more effective than rhymes in creating a sense of patterning, so think about repeating certain words or phrases, or repeating the sentence structure.

If you’re using a consistent metre, lines generally turn out to be about the same length. If you aren’t using metre, however, line length can vary widely. There’s no rule against this, but make sure any drastic variations are intentional and not unintentional. Random line or stanza lengths can make a poem feel scattered and disjointed – this may be precisely what you are after, so be sure that this is something you are doing on purpose and to achieve a particular effect.

Read your poem aloud. Sometimes writing can look good on the page but be very difficult to read aloud. Some word combinations just don’t flow off of the tongue very well, and until you hear it, it can be difficult to catch those problems.

Poems don't have to rhyme. Some poems sound better with a few rhymes, but not every single line ending in a rhyme. So you may want to consider taking a look at your poem. Can you add a few rhymes to make it better? Take away a few?

You can use:

Full rhymes e.g. dog, hog, log Near-rhyme e.g. far, bear, soar, or dark, sharp, shirt Assonance e.g. green, fiend, heapedConsonance e.g. kicked, capped, kistAlliteration e.g. short, ship, shore

12National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

3.3 Extension writing tasks

3.3.1 For P6–S2

War Memorial

Visit a local war memorial. (There may be one in your school.)

Look at the words that are used on it. Are there any unusual or unfamiliar words?What do they tell you?

Look at the imagery that is used, and describe it. If there is a figure or figures on the memorial, describe

what they are wearingwhat they are holdingthe position of their bodyany gestures they are makingthe expression of their facetheir relationship to any other figures beside them

Look at the list of names on the memorial.

Are there any names you recognise?Are there any unusual names you don’t recognise?

Choose one of the names on the memorial, and write a letter to that person.

Tell them what you have learned about the war which they fought in.Tell them about what is happening locally now – in school, in town, in the area.Tell them about wars that are being fought today.Ask them a question about their war experience.Tell them your hopes for the future.

13National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

3.3.2 For S3–S6

Making a Humument

This is an exciting multi-arts creative challenge, equally relevant for students of History, English or Art, and so you may wish to work with other department colleagues to plan and deliver a larger cross-curricular project. In particular, the exercise

- offers history students opportunities to interpret and comment creatively on a factual text they’re reading

- offers English students opportunities to explore tension in language and to reconfigure a set text to (re)create ‘found’ or concrete poetry

- offers art students opportunities to work with language and the printed page as visual stimulus and raw material

Human + document = humument

The term ‘humument’ was coined by artist Tom Phillips (http://humument.com/). Making a ‘humument’ involves the manipulation of an extant text to create ‘found’ poetry or ‘art from an extant text’.

Once you’ve familiarised yourself with the range of relevant techniques, offer students photocopies of a page or pages from a relevant history text book. (Books of soldiers’ testimonies are particularly rich for the purpose too – although one must take care to treat them with respect and integrity. See below at 3.3.3) Or offer a primary source text such as a newspaper article or a letter.

Make a ‘humument’ out of it -

by erasing or parenthesising certain words to link those that remain by highlighting words to draw attention to them by extracting words and setting them down on paper to sit next to the

original text

- to create an interpretation of the text that is a ‘poem’, or more broadly, a work that is a fusion of language and art.

For example, students can add illustrations (representative and abstract), and use colour.

14National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

3.3.3

Making a Found Poem

War testimonies, by their nature, are often profoundly personal, painful, tragic, and require due respect. If you want to use soldiers’ war testimonies on which to base a poetry exercise, you may find it more appropriate and respectful to explore creating ‘untreated found poetry’ rather than a ‘humument’, as above. In this way, students need not find themselves defacing or overtly manipulating sensitive material. ‘Found’ poetry is a form created by taking words, phrases or passages from existing texts and reframing them as poetry by making changes to impart new meanings and significances – like literary collages. Found poetry is often made from fiction, non-fiction, newspaper articles, street signs, graffiti, speeches, letters, or even other poems.An ‘untreated’ or ‘pure’ found poem to a great extent retains its original integrity; it is made by simply re-shaping the original selected text but leaving it virtually unchanged in terms of its order, syntax and meaning, so that creation of lines, line breaks, stanza breaks, punctuation (and perhaps use of repetition) are the principal creative tools. (A ‘treated’ found poem can be made by adopting a wide range of techniques: re-ordering, adding to or deleting text from one or more original sources. The resulting new poem may bear little relation to the appearance, purpose or intent of the original text, and may impart additional or different meanings or significance.) If you would like to explore further the use of soldiers’ testimonies as inspiration for poetry, have a look at the short collection of poems, The Not Dead, by Simon Armitage (Pomona, 2008). These war poems were adapted from the testimonies of real soldiers suffering Post-Traumatic-Stress-Disorder.

15National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

3.4 More Poems to Read Together

Here is a list of other poems on the subject of war and remembrance.

For P6–S2

Carl Sandburg (1878–1967), ‘Grass’Available online, at for example http://www.bartleby.com/104/78.html

Find out about the places mentioned in the poem – where they are, what happened there, and when.The grass says, “let me work”. What work will the grass do?

Dirk Bogarde (1921–1999), ‘Salvage Song (or: The Housewife’s Dream)’in The Voice of War: Poems of the Second World War (ed. Selwyn, 1995)Note: Hurricanes’ and ‘a Dornier’ are types of aeroplanes.What other household items can you imagine might have been melted down to make arms? What, other than aeroplanes, might they have been made into? Make up your own combinations of metal household items and armaments.

Jim Blaikie, ‘Air Raid’in A Laddie Looks at Leith by Jim Blaikie (Hobby Press, 1993)This describes an air-raid on Edinburgh during the Second World War from a child’s point of view.What is dropped from the “German aircraft”?What effect does it have when it hits the ground?What damage does it cause?

Myra Schneider, ‘Drawing a Banana (A Memory of Childhood during the War)’in Insisting on Yellow: New and Selected Poems (Enitharmion, 2000)The schoolchildren in the poem have been told to draw a banana.Why was it so unusual to see a banana in Scotland during World War Two?What does the child in the poem want instead of the banana?What does war mean to the child in the poem?

For S3-S6

W.B. Yeats (1865–1939), ‘An Irish Airman foresees his death’16

National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013

Available online, at for example http://www.bartleby.com/148/3.htmlHow would you describe the speaker’s attitude to warthe dangers he faceswhat he is fighting for

Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918), ‘Break of Day in the Trenches’Available online, at for example http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/break-of-day-in-the-trenches/The poem is addressed to a rat. What can the rat do that the soldier cannot? What do you think the rat represents to the poet?What do you think the poppy represents to the poet?

Keith Douglas (1920–1944), ‘How to Kill’Available online, at for example http://www.ppu.org.uk/learn/poetry/poetry_ww2_2.htmlWhat happens in this poem? How does the speaker feel about what he does? Why is ‘death’ presented as a ‘mosquito’?

Edward Thomas (1878–1917), ‘In Memoriam (Easter 1915)’Available online, at for example www.poetsgraves.co.uk/Classic Poems/Thomas E/in_memoriam_(easter,_1915).htm (for the poem’s background see also HYPERLINK "http://war-poets.blogspot.co.uk/2010/04/edward-thomas-in-memoriam-easter-1915.html" http://war-poets.blogspot.co.uk/2010/04/edward-thomas-in-memoriam-easter-1915.html)

How long had the war lasted when this poem was written? How long would it still continue?

What do the flowers represent to the poet?Why do you think the poem is set ‘at nightfall’, rather than, say, ‘at daybreak’ or

‘this morning’?Why do you think the poem mentions Easter, rather than, more generally, ‘spring’?

17National War Museum & Scottish Poetry Library Ghosts of War Education Resource Pack 2013