| The Zensory Lightness of Being | The Sovereignity of Detachment over other Concepts, a...

-

Upload

faunerevol -

Category

Spiritual

-

view

302 -

download

1

Transcript of | The Zensory Lightness of Being | The Sovereignity of Detachment over other Concepts, a...

1

T H E Z E N S O R Y L I G H T N E S S O F B E I N

G

| The Sovereignty of Detachment over other Concepts - A Contemplation

of the Good |

‘I think there is a place both inside and outside religion for a sort of

contemplation of the Good, not just by dedicated experts but by ordinary

people: an attention which is not just the planning of particular good

actions, but an attempt to look right away from Self towards a distant

transcendent perfection, a source of uncontaminated energy, a source of

new and quite undreamt-of virtue. This is the true mysticism, which is

morality’ […]’1

Referring to Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being’ dealing with

the main thought ‘’each man has only one life to live’, a life in which that

what occurs, occurs only once and so forth never again hence imposing a

certain unbearable lightness on being, this essay explores its ‘bearable’

potential; a Modeless Mode of Being2 in which particular being, self-being,

has been transcended. A Modeless Mode of Being, a ‘Zensory’3 Being in

which The Good can be grasped according to Christian mystic Meister

Eckhart. Opposed to Nietzsche’s concept of eternal recurrence -

associated with the thought the universe and its events have already

occurred and will recur ad infinitum, imposing a certain ‘heaviness’ on

one’s being - Kundera’s concept of lightness underlines the rather

insignificance of one’s being - for decisions do not matter and are

1 From: Iris Murdoch, ‘The Sovereignty of Good’ (1985) in: (Crisp and Slote, 1997: 116). 2 ‘A Modeless Mode of Being’; a concept of Meister Eckhart to refer to that ‘mode’ – although being ‘modeless’ in which all particular modes of being are transcended and Unity is experienced. Beginning with capitals this Modeless Mode corresponds with the Divine, Unity in which All is One. ‘Good’ is therefore written as well with a capital to refer to a Modeless Mode of Goodness in which all its particular modes are transcended.3 ‘Zensory’: a term conceptualized to describe what Eckart calls a Modeless Mode of Being. More explanation will be given further in this essay.

2

therefore perceived light not causing personal suffering. On the other

hand this insignificance of one’s being is causing suffering in the

awareness of the transience of life occurring once and never again: an

existential lightness becoming unbearable for Man generally wishing his

being to have transcendent meaning. The unbearableness lies in the

attachment to the value of one’s individual life lived by ‘self’ and it is the

letting-go of this attachment, a detachment, which generates the

transcendent meaning or significance Man would search for; his mystical

nature, generating a ‘bearable’ lightness of his being. Functioning as a

metaphor to pave the path towards what could be perceived as the ‘Holy

Grail’ of morality, grasping it’s true mystical nature, Kundera’s idea of

lightness will be perceived from its other side. A contemplation4 of the

Good by looking away from self towards a distant transcendent

perfection, towards a new source of virtue, a viewpoint expressed by

moral philosopher Iris Murlock – in favor of the use of metaphors herself -

and quoted above.

It is the mystical nature of morality, a contemplation of Good following

Murdoch, this essay attempts to explore in larger depths by traveling

through the mindscape of Christian mystic Meister Echkart and his

doctrine5 of redemption, wherein the human being becomes a Homo

Divinus, an incarnation of the Divine or God6, the Godhead. Since

Murdoch has stated a contemplation of the Good would be possible for

her both inside and outside religion, the choice for Eckharts’s mystical

doctrine rooted in Christianity could be considered an extra validation

regarding its use. The question why an exploration of the mystical nature

of morality would matter should be understand in the context of

4 Contemplation is a concept of utter importance as well in both the thoughts of ancient philosophers Plato and Plotinus. Former states it is through contemplation the Divine Form of Good can be grasped, the highest object of knowledge only accessible for philosopher-kings. Latter constitutes contemplation as the way to reach Henosis, a state of Oneness.5 – Or ‘living realization’ for the mystic approach emphasizes direct experience over doctrine. To speak about living realization in light of discussing mystical thought seems however not suitable: the purpose of this essay is to explore mystical ideas by means of analyzing them, grasping them to theoretical extent. To realize their content and transcent their theoretical dimension, agreement is there, words should be realized in living deeds.6 In his Sermons Eckhart mostly uses the ‘concept’ of God to name the Divine, he mentions though that ‘God has no name’. It is herefore this essay uses Divine as a concept instead of God to refer to itself for former is a concept less loaded than latter. Secondly awareness is there, the word is not capable to grasp the true essence of the Divine, that is by experience only as the mystical approach implies. Thirdly the Divine is ‘the solitary One’, being both transcendent and immanent (Shah-Kazemi, 2006:136).

3

Murdoch’s stating moral philosophers should attempt to answer the

question: how can one make oneself better7? If life would occur once and

never again, as Kundera presupposes, there would be no higher

improvement of one’s being than by perfecting it and it is the perfection

of virtue, a contemplation of the Good, grasping it’s mystical nature,

which could be considered it’s glorious finish. According to Murdoch it is

one’s task to come to see the world as it is and in order to do so, Man has

to sacrifice all to come to this essence. This is what the mystic attempts,

to dis-cover the Essence of Being.

A contemplation of the Good implies according to Murdock a looking

towards a transcendent perfection of virtue, what seems to be a

pleonasm when aligning it with the thoughts of Meister Eckhart. About the

relation between transcendence and virtue Eckhart argues the ability to

transcend limitative conceptions, so too in relation to a conception of

virtue, presupposes their existence as a foundation for this transcendence

potential. Perfection of virtue as such could be considered in so far a

transcendence of any kind of particular virtue, a-going-beyond for which

all virtues have to be realized 8.

‘[A]ll virtues should be enclosed in you and flow out of you in their true

being. You should traverse and transcend all virtues, drawing virtue solely

from its source in that ground where it is One with Divine9’.

The essence of all virtues should be assimilated to such extent they all

emanate, ‘flow’ from man supernaturally, beyond his self-being. A

looking towards a perfection of virtue should therefore be detached of

any particularizing conception of virtue realized beforehand in order to

make transcendence, hence perfection possible. The limitation is in the

attachment of the particular, to detach is to transcend this particular,

hence to grasp essence hence to perfect. Transcendence is therefore

perfection by which the pleonastic nature of Murdock’s expression of

‘transcendent perfection’ becomes clearly visible. Eckhart agrees on the

7 From: The Sovereignity of Good over other concepts of Virtue (1985) in: (Crisp and Slote, 2007:100).8 From: (Shah-Kazemi, 2006:143).9 From: (O’Connell Walshe, 1979, I:128).

4

essentialism of detachment, he argues transcendence of virtue can be

realized only indeed by looking away from the particular he associates

with a looking away from self connected to the ‘created world’ by

conforming one’s will to the Divine Will. He states the Divine Will is

necessarily Good and so man must necessarily accept and be ready for

everything that is the Divine Will in order to improve one’s being to the

highest extent possible.

‘I find no other virtue better than a pure detachment from all things,

because all other virtues have some regard for created things, but

detachment is free from all created things [..] He who would be serene

and pure needs but one thing, detachment."

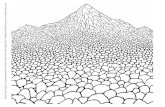

Pure detachment he associates with an immovable stand of spirit10 in all

assaults of feeling of joy, sorrow, shame like a stand of a solid tree rooted

in the earth not blown away by a raging storm. Here immovability rather

should be understood as a firm-being-rooted able to go with the flow of

feeling as it appears being not overwhelmed by it, not attached to it,

letting be whatever is, without judgment, preference or meaning. This

immovable stand would bring man in the greatest similarity with the

Divine. Initially detachment for Eckhart signifies a notion of will

constituted as a ‘not-willing’ a certain cessation of will, where particular

will fades away in order to become receptive to the Divine will, where

possessing and having are eradicated and where one’s own needs and

interests are renounced in the interest of another’s: the Divine11.

Receptivity, for Eckhart strongly emphasizes the importance of complete

disappearance of individual will to become as ‘fully empty’ needed to

receive the Divine, for that will enter a detached, hence, ‘free’ soul12:

"To be empty of all created things is to be full of ‘God’, and to be full of created things is to be empty of ‘God" […]

10 Spirit: not guided by self/thinking from subject, but rather a just-being, a letting-flow equal to the stand of spirit the Buddhist tradition of Vipassana meditation describes.11 From: Selected Writings. Trans. Oliver Davies. New York: Penguin Books USA, Inc., 1994, p. 24412 From: sermon 24 - ‘Free’ or ‘pure’ as mentioned in the first quotation. What Eckhart exactly means by Soul remains unclear for he does not give an elaboration on it and/or uses other concepts to describe it.

5

According to Eckhart, the Divine is ‘No-thing’ – rather the Being that

undergrids all reality. Man must become no-thing to be one with Divine. It

is the concept of Kenosis, rooted in Christian theology, which also refers

to this process of self-emptying': releasing one's own will and becoming

entirely receptive to the Divine13. This process of self-emptying is what

could be understood as an increase of sensitivity to its full potential, a

potential hidden in man, though regularly covered by a veil of self-

interested will. It is the moral philosopher Malcolm McDowell, who also

introduces the concept of sensitivity to the field of virtue relating it to a

sort of single complex perceptual capacity, an ability to recognize

requirements which situations impose on one’s behavior14. Virtue he puts

on a secondary place in moral philosophy when attempting to answer the

question ‘how should one live’ in universal conceptions. Although

differently formulated than Murdock’s question ‘how can one make

oneself better’, both questions are connected for ‘how to live’ in view of

moral philosophy implicitly deals with ‘to live good’ as does ‘to make

oneself better’ for ‘better’ is an improvement of good. Secondly to live

good automatically could imply to aspire to make oneself better for to live

is to be in motion, to develop, which opens dimensions for learning hence

improvement. Turning back to the secondary place McDowell puts virtue

on in light of these questions, it is the ‘being a kind of person’ –

perceiving life and events in a certain way – he puts on the first place.

This ‘kind of being’ seems to overlap strongly with Eckhart’s notion of a

‘mode of being’ when he introduces a ‘Modeless Mode of Being’, a

negation of a negation of a ‘mode of being’ in attempt to constitute a

transcendent mode of being – for even the concept of mode is in this

modeless mode transcended - that being in which detachment is fulfilled

and a ‘Breaking Through15’ manifests itself.

13 With reference to Kenosis: here it stands for becoming receptive to the Divine as in: ‘Christ emptied Himself’ (Philippians 2:7) The common view to Kenosis is derived from German theologist Gottfried Thomasius (1800) stating Christ gave up voluntarily some of His divine attributes - omniscience, omnipresence and omnipotence - so he could function as a man on earth to fulfill the work of redemption. Note that here the emptying factor is in the letting-go of divine attributes, whilst concerning Man, the emptiness is in the letting-go of one’s own – human – will to receive the Divine. The question raises if this Divine would be similar to the Divine attributes Thomasius mentions. 14 From: ‘Virtue and Reason’ (1979) in: (Crisp and Slote, 2007:142,144,161 and 162).15 Breaking-Through: When the self is fully detached and the veil of the created world has vanished entering the Modeless Mode of Divine Being.

6

‘’Therefore, I say, if a man turns away from self and from created things,

then - to the extent that one will do this16 - one will attain Oneness and

blessedness in one’s Soul's spark, which time and place never touched’’

[…]

According to Eckhart all perfection, all blessedness depends upon the

Breaking Through, which is beyond the created world of temporality

entering the ground that is without ground17. In this Breaking Through

every mode of being hence every conception is transcended and a

Modeless Mode of ‘Oneness18’ Being manifests beyond the limits of

ordinary sensory experience though being possible to grasp by direct

experience for this is the mystical approach. The kind of direct experience

in this Modeless Mode is difficult to conceptualize for it impoverishes its

nature – as do all signifiers in relation to their signifieds - nevertheless in

order to be communicated, one needs a signifier signifying the signified.

In this case the nature of the signified it is even more problematic for

here the signified is something which in fact cannot be signified by a

signifier, for it is beyond being and it is within being this potential lies.

Eckhart attempts to overcome this by his expression of ‘Modeless Mode,’

and another suitable term approaching it to a large extent seems to be

‘Zensory’ experience, the Modeless Mode wherein the ‘Now’ is

experienced, ‘Presence’: ‘never touched by time and place’ for Eckart

insist one must flee one’s senses and turn inwards to break through19.

This fleeing one’s senses could be understood as a ‘Stateless State’ of the

senses, in which they are transcended – a- going-beyond the ordinary

senses, generating hence a ‘Zensory’ experience.

Concepts as ‘Zensory’ and ‘Modeless Mode’ serve merely as metaphors in

the attempt to grasp and communicate about the existence of Oneness,

for it has to be underlined again they represent a mode of Being which

16 To the extent – to the fullest extent means total detachment of individual will.17 From: (‘O Connell Walshe, 2008: sermon 80).18 Oneness: and not unity, which is also associated with this Modeless Mode, Eckhart strongly insists on Oneness as opposed to united-ness of which latter corresponds with a coming together of things, which still remain rather get unified. Oneness merely is where two are become one and wherefore one has to loose its identity. In de Modeless Mode of Being, the soul gives up her being and life to become One with Divine, which stays. The soul does not perish for Divine, for it is Divine which brought soul out of itself, therefore soul must be truly its (‘O Connel Walshe, 1979: I-184).19 From: (Shah-Kazemi, 2006:158).

7

actually cannot be catched in words for to speak or to write is to

particularize. However, a particular mode of being is the prerequisite for

understanding of its limitations nourishing the need to become One and

thus Good and transcend particularity. As was mentioned in the beginning

of this essay, it is the existence of concept which makes its

transcendence/perfection possible leading to Breaking Through and to

experience Divine: Oneness. Oneness is therefore immanent in concept

as such. This could be extended to the thought, it is the existence of man,

which makes his transcendence/perfection possible, making this Oneness/

the Divine also immanent in him. This becomes even more clear when

Eckhart argues it is Divine revealing itself in man after he becomes

detached from self-being and transcends this beingness in the Breaking

Through, this he calls, the Godhead in man. Here Eckhart’s mysticism

shows both elements of transcendence and immanence. The Divine

made the soul not merely like the image in Himself, but like His own Self,

in fact like All He is. Man, as in particular ‘self’, only has to step out of the

way, which is the only thing man in fact ought to do in life, however still

turns out to be the greatest challenge he is confronted with:

‘God is always ready, but we are unready. God is near to us, but we are

far from Him. God is in, we are out. God is at home in us, we are

abroad20’.

Turning back to the doubtful nature of the ‘Modeless Mode of Being’

concept, this is the great challenge all schools of mysticism21 are facing

and are criticized for by the scientific field22, it shows again why emphasis

is put on direct experience over written doctrine by the mystical

approach. On the one hand, one might wonder how to live according to

the mystical approach of being if no doctrine of this approach would be

available to orient one’s being to, on the other hand, one might become

alienated by living up to other’s doctrine potentially blinded for one’s own

20 From: (‘O Connell Walshe, 2008: sermon 69).21 ‘All schools of mysticism’: respectively all groups of agents representing a tradition of mystical philosophy in which certain concepts, structures and systems of meaning are created to signify to the Mystery of being, the Divine. 22 Field – as in the Bourdieuan concept of field: a setting in which actors and their positions are located by processes of interaction among the specific rules of the field, the ‘Habitus’ an actor reflects and his possession of ‘Capital’; cultural, economical and social. A social arena in which actors maneuver in pursuit of desirable resources (Bourdieu, 1984).

8

experience. Eckhart adds to this man must have assimilated a certain

degree of doctrine and live according to the virtues derived from this

doctrine in order to make transcendence, perfection, possible. To what

extent what doctrine should be assimilated en which virtues are following

from that is however not clear. Dealing with Eckhartian mysticism, it

seems the teachings of Christ are preferred since Eckhart’s mystical

thought itself is rooted in Christianity23. On the other hand, it is

considered the mystic’s being not to be attached to any kind of doctrine,

conception or preference, which again shows the rather complicated

nature of what path to walk to reach transcendence. The only certainty is

that at least one or another path has to be walked, for as to Rome, it is a

multitude of paths leading to the Breaking Through, chosen paths, which

one has to let go eventually when completely internalized. And this is

exactly the challenge man has to face: to become conscious of one’s

internalized path, doctrine completely mastered and to detach from it

again to every extent possible without escaping to another one. Speaking

about ways to embed to one’s being the how-to question concerning

detachment, ingredient to reception of the Divine will, hence

transcendence of the limitative created world, hence perfection and the

experience of Breaking Through, Eckhart indeed mentions the potential

danger of escapism, here conceived as a search of peace in external

things:

“Make a start with yourself, and abandon yourself. Truly, if you do not

begin by getting away from yourself, wherever you run to, you will find

obstacles and trouble wherever it may be. People who seek peace in

external things - be it in places or ways of life or people or activities or

solitude or poverty or degradation - however great such a thing may be or

whatever it may be, still it is all nothing and gives no peace”.

Eckhart underlines the importance of the detachment of all external

things opening the way for what he perceives as the key leading to

Breaking Through, an opening of the doors of the created world. This

opening, or more precisely stated ‘re-opening’ or ‘dis-covering’ of the

world is exactly the core of French phenomenology as represented by

23 Thereafter Eckhart speaks about assimilation of the ‘lofty teachings of Christ’ (Shah-Kazemi, 2006: 134).

9

Merleau-Ponty although he disagrees with the possibility to transcend the

I and enter what Eckhart constitutes as the Modeless Mode of Being, the

Now, receiving Divine. He states there can be no self-enclosed Now

experience of time, because time always has a reflexive aspect being

aware of itself, opening man up to experience beyond particular horizons

of significance. This temporal alterity causes man can never say ‘I’

absolutely (PP 208) for:

“I know myself only insofar as I am inherent in time and in the world, that

is, I know myself only in my ambiguity24” […] ‘Subject is time and time is

subject’ [...]

Despite this difference in perception of Now, Merleau-Ponty ascribes

man’s inherent ‘mode’ of being in the world and time as dependant on

intentionality, directed by the stretch of one’s intentional arch. It is by

being as such the world opens itself: a particular mode of being generates

a particular opening of the world: being is to be in the world. The tighter

one’s intentional arc is stretched, the more open the world will be.

Because Merleau-Ponty states ‘subject is time and time is subject’ – in

abstracter terms translated in a = b and b = a, following the rules of

logic from it can be derived, that -a = -b and –b = -a – transformed to

concrete terms again: no-subject is no-time and no-time is no-subject.

And although Merleau-Ponty discloses an existence of a Now state as

explained earlier, the negation of his assumption makes this Now state

possible, in which there is no time and no subject according to Eckhart. It

is precise the detachment of self (subject) letting it fade away resulting in

an absence, an emptiness ‘Breaking Through’ its subject-existence and

with it all its creations such as time, entering this Modeless Mode of Being

in which hence no subject and no time exist. One could say in this

Modeless Mode of Being one’s intentional arc is stretched that far it snaps

and everything simple is for even a particular mode of openness is

transcended in the Modeless Mode. Merleau Ponty’s statement ‘The world

is wholly inside and I am wholly outside myself25’ is thus valid in so far I

and the world are distinctive, which is the case in this particular mode of

24 From: (Merleau-Ponty, 2009: 345, 431 and 432).25 From: (Merleau Ponty, 2009: 407).

10

‘being in the world’, however when mode is transcended to a Modeless

Mode, concepts as world, I, inside and outside do not matter anymore.

Using Merleau-Ponty’s metaphor, it is detachment from I – subject –

bringing one’s intentional arch to snap. Eckhart underlines this should be

a purity of intention cut off from individual will with no falling back on

admixtures for – ‘however their greatness’ – they are limitative and

therefore cause alienation from essence26. Again difficulty raises

regarding an understanding of what this essence exactly might be since

Eckhart presupposes it is nature to be without nature from which follows

that, to think of goodness or any other concept dissembles Good

(essence), it is putting an impermanent veil over the immutable nature of

the Universal Good. It dims it in thought for the mere thought obscures

essence27 for a particular good adds nothing to goodness, it rather would

hide and cover the goodness in man. So mental thinking of goodness veils

the Good, for Good, its true nature, is incompatible with human thought

limiting and distorting it. It is Thomas Kuhn’s concept of

‘incommensurability’, which seems to be in place here, explaining this

gap between concept and reality as a rely on different contexts – that of

mental thinking and of direct experience, two contexts, which are

incomparable.

With ‘no falling back on admixtures’ (external things), Eckhart means all

things outside of the inner life, a falling back on any other doctrine, belief,

conception dealing with the outer life. In fact this then also includes

doctrines stating how to enter one’s inner life for it is the statement, the

belief of the how-to, which would seem to lead one away from one’s own

experience. In this view even Eckhart’s focus on detachment becomes

doubtful for it is still a how-to means, a way, to become empty in order to

receive the Divine. Aware of this, he arguments detachment is the ‘key’

virtue standing above all doctrines with forthcoming particularized

conceptions of virtue related to self, for it is not associated with self, in

contrast, detachment presupposes the leaving of self in order to

transcend it. It is about pure intention, as seeking Divine for its own sake,

26 From: (O’Connell Walshe, Vol.II: 39).27 From: (O’Connell Walshe, Vol.II: 32).

11

what ‘true’ detachment implies, only man, who abandons all for Divine’s

sake, who does not consider anymore this or that good, that man will

have Divine, Good and all things with Divine and because of that

detachment in its true nature is the best of all virtues. For to have Divine

is the highest man can achieve in soul. About this seeking Divine for its

own sake he adds, one should want nothing, also not an experience of

Divine in one’s soul and be free of all knowing so one will not know that

Divine is in one’s soul. The only thing one should ask is to become a

place only for Divine, ‘in which It can work28’. Man should therefore not

worry about what one does, rather what one is29.

Although Eckhart takes it for granted man attempts to live a moral and

regular life, he considers it not enough for he sums up a few reasons

preventing man from attainment of ‘true’ detachment. The first reason is

the soul being too scattered being too much distracted by the external

created world. The second reason is the soul’s involvement with transient

things, which in fact could be considered a distraction as well. The third

reason is an excessive focus by the soul on bodily needs, preventing the

soul from its growth towards union with Divine and to become One30.

Except these three reasons Eckharts recommends ‘absolute stillness for

as long as possible’ as a necessary means on one’s way to become

receptive to Divine. On the other hand, he warns man walking the path of

stillness hence contemplation, not to abandon one’s inner life, rather flow

with it in such a way that inward life spontaneously breaks out into

outward life, activity, which will lead back into inward life again. Here the

metaphor of the labyrinth, the ancient mystical symbol for tending of the

soul seems to be of value. The labyrinth is unicursal having one way into

the center and one way out symbolizing the ‘decensus ad inferos’: the

descent into the bowels of ‘symbolic’ death and return to life reborn.

Thereafter it is associated with the symbolic ‘conjunctio oppositorum’: the

place in which duality comes together as in a spiral being transcended

and becoming One31. Eckhart’s idea of going inwards (descending)

28 From: (O’Connell Walshe, 2008: sermon, 87).29 From: (O’Connell Walshe, 2008: Talks of Instruction 4).

30 From: (O’Connell Walshe, 2008: sermon 85).31 From: (Eliade, 1969).

12

leading to going outerwards (returning) leading back to going inwards and

so on in itself could be considered an example of both explanations of the

symbol of the labyrint, descending and returning as also in its totality as a

process of coming together of duality (inner and outer) in the flow, the

movement.

Following this logic of the labyrinth, it seems it is in this movement,

immersion of soul can take place, the true detachment from self,

emptying one’s being to become this place where ‘It’, hence Divine, can

work. For to be completely in the movement, in the flow, is where the self

will take its rest, where Man becomes detached from it’s self-being

opening up to receive Divine and man will not seek it for it happens to

him being in this flow, this is truly the Modeless Mode of Oneness Being,

the Zensory lightness of Being for here man (self) is completely merged

into Divine, ‘Now’ and therefore does not even know God is in him. It is

thus in the movement All becomes One hence the Good will be known,

the true mystical nature of morality, its Essence as also all other mystical

natures of concepts for in this Modeless Mode Oneness reigns, Perfection.

True Creation lies in the movement. Turning back to Murdock, this essay

started with, it is also her, who refers to detachment from self as the way

most likely to become Good.

‘It is the humble man, that man, who sees himself as nothing, will see

other things as they are - for he is detached from self - and although he is

not by definition ‘Good’, he is the most likely of all to become Good’32.

And from this viewpoint it can be concluded, detachment indeed seems to

be sovereign over other concepts of virtue nevertheless man should stay

indeed ‘humble’ in one’s belief about morality still being able to detach

from it in order to make transcendence hence perfection possible,

Breaking Through to become Good rooted in that Zensory Lightness of

Being, in which All is One…

...‘letting go they went comfortably to sleep. It was All Right’…

32 Murdoch in: (Crisp & Slote, 2007: 117).

13

B I B L I O G R A P H Y

Bourdieu, P. (1984), ‘La Distinction; a Social Critique of the Judgement of

Taste’, Sage Publications, London.

Eliade, M. (1969), ‘Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism’,

Sheed and Ward; Search Book Edition, New York.

McDowell J. (1979), ‘Virtue and Reason’, The Monist, 62, pp. 331-350 in:

Crisp, R. and Slote, M. (2007), ‘Virtue Ethics’, Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

Meister Eckhart (1994), ‘Selected Writings’. Translated by Oliver Davies,

Penguin Books USA Inc., New York.

14

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2009), ‘De Fenomenologie van de Waarneming’, Boom

Uitgevers, Amsterdam.

Murdoch, I. (1985), ‘The Sovereignty of Good’, Ark, London in: Crisp, R.

and Slote, M. (2007), ‘Virtue Ethics’, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

‘O Connell Walshe, M. (1979), ‘Meister Eckhart: Sermons and Treatises

(Vols. I-III), Element Books, Dorset.

‘O Connell Walshe, M. (2008), ‘The Complete Mystical Works of Meister

Eckhart’, Crossroads Herder, New York.

Shah-Kazemi, R. (2006), ‘Paths to Transcendence according to Shankara,

Ibn Arabi and Meister Eckhart’, World Wisdom Inc, Bloomington, Indiana.

15