© Peter Dammann/Greenpeace The cod fishery in …...3 The United Nations (UN) states that the main...

Transcript of © Peter Dammann/Greenpeace The cod fishery in …...3 The United Nations (UN) states that the main...

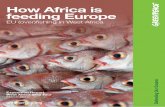

The cod fishery in the Baltic Sea:unsustainable and illegal

© Peter Dammann/Greenpeace

© Wolfgang Steche/Greenpeace

© Wolfgang Steche/Greenpeace

2

Executive Summary 3Introduction 3Cod fishing – vacuuming the ocean floors 4Dwindling stocks 6The fishing fleets 8

Pirate fishing in the Baltic 9Baltic cod travel far on land 12The political level 14Conclusions and Demands 15Bibliography 16

Contents

3

The United Nations (UN) states that the main factors determining biodiversity loss in ouroceans are overfishing and climate change. Cod is a case in point. Once so dense that fishcould literally be scooped out of the sea, the majority of the cod stocks worldwide are nowcommercially extinct, or very close to it. This is true in the Baltic Sea, particularly for theeastern stock.

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES: the scientific advisorybody for the northeastern Atlantic region) and the European Union (EU) are calling for adrastic reduction of quotas, or even for a cessation of cod fishing in waters of the easternBaltic Sea.

However, the dire warnings from ICES have been ignored in the past, and there is no rea-son to be more optimistic this time. For instance, the Council of Fisheries Ministers of theEU has set the 2006 total allowable catch for Eastern Baltic cod at a level more thanthree times that advised by ICES. In addition to the official quota of 49,000 tonnes, ahuge amount of illegally caught cod is landed in harbours around the Baltic Sea for consumption within the EU market. ICES estimates that in 2005, the amount of illegallycaught cod reached close to 15,000 tonnes, which is 38 % above the official landings. The Polish fleet, in particular, is fishing above its allocated quota. This report summarisesthe disastrous situation, gives an overview of the Baltic cod fleet and markets, anddescribes the EU’s political approach to managing Baltic cod fisheries, which may beviewed as a failure to this point in time.

Introduction

Cod has been an important commercial species for centuries. As early as the 14th century,it was this species that led Basque fishermen as far west as the east coast of NorthAmerica. The once rich stocks provided the Basques’ a bountiful harvest that was dried,salted and sold all over Europe as the still famous ‘bacalao’.01 The cod stock of easternCanada, however, has long since disappeared destroyed by a voracious fishing industryoverexploiting the once immense wild populations. Following the stock collapse, a ban oncod fishing was introduced in 1992, coupled with aid for fishermen who were put out ofbusiness. However, for political reasons, fishing was allowed again between 1995 and2003. The stock of eastern Canada has never recovered and there is now a belief that itnever will. The cod stocks in the North and Baltic Seas are similarly overexploited beyondany sustainable level. These eastern Atlantic populations may share the same fate as theCanadian stock. This report focuses on Baltic cod stocks. The Baltic Sea is inhabited by two distinct stocks- one heavily exploited, the other at the brink of commercial extinction. As in other seasand oceans, scientists are calling for stricter protection of cod, while politicians continueto disregard this advice, jeopardising the future of the fishing industry itself, the fishstocks and the ecosystems in which they live.

Executive Summary© Wolfgang Steche/Greenpeace

4

Cod fishing – vacuuming the ocean floors

Cod (Gadus spp.) is a marine, cold water and mainly bottom-dwelling species. It feeds ona diversity of animals, including worms, shellfish, squids and also other fish, which may betheir own offspring.

The genus can be found in all areas of the northern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, includingthe Baltic Sea. In the Baltic there are two distinct stocks, viz., the Atlantic or western codstock (subspecies Gadus morhua morhua L.) and the Baltic cod, also known as the easterncod (subspecies Gadus morhua callaris L.).

here: Figure 1

Atlantic cod inhabits the Baltic areas west of Bornholm Island, including the waters of theDanish Straits. Baltic cod, on the other hand, can be found only in the central, easternand northern parts of the Baltic Sea. The main spawning season is between June andAugust. The fishery targets mainly pre-spawning aggregations in late winter and spring.02

Cod reaches the limits of its distribution in the Baltic Sea, where the salinity decreasesfrom west to east, reducing to almost fresh water levels in the northern and easternmostareas. This is not much a problem for mature cod, but does affect juveniles and reproduc-tive capacity of the species. At low salinity, the eggs sink out of the oxygenated surfacewater (where they are able to mature) into deeper oxygen-poor layers.

In these deep layers, oxygen originates from regular inflows of water from the North Sea.Strong autumnal storms usually push heavy salt- and oxygen-rich North Sea surface waterinto the Baltic where it sinks, carrying oxygen into the deep. However, the rate of NorthSea water influx has declined drastically over recent decades, leading to anoxic (oxygen-

5

deficient) conditions in the deeper layers, with very poor cod recruitment.03 At the sametime, elevated nutrient loading in the Baltic Sea has led to increased phytoplankton production, with associated reductions in dissolved oxygen during decomposition of algalcells following bloom conditions. As a consequence, anoxic conditions now prevail in vastareas of the Baltic seafloor, including the Bornholm Deep.04

This concatenation of circumstances has resulted in the existence of only one functioningspawning area for cod in the eastern Baltic Sea, the Bornholm Deep, with the Gdansk andGotland Deeps being suitable only in those years in which there has been a strong influx ofNorth Sea water.

Cod and its ecosystem importance

Apart from providing a living for thousands of fishers and workers in secondary indus-tries who supply healthy protein for the human diet, cod is also a key component in themarine ecosystem of the Baltic Sea. The food web in the central Baltic Sea is normally controlled by cod and its main prey,sprat and herring. The decrease in the cod stocks, due to adverse environmental condi-tions and overfishing, has considerably lowered the pressure on prey species. The mainbeneficiary of this has been sprat, which in addition to losing its main natural preda-tor, has never been exposed to heavy fishing pressure, unlike herring. Sprat, in turn,feeds on cod eggs and competes with herring for food. When the cod stocks werestrong, as in the 1970s and 1980s, so too was the herring stock, both supporting eco-nomically significant fisheries. Today, sprat dominates, with cod and herring beingharvested at very low, yet unsustainable levels. The fishery changed from supplyingvaluable protein for human consumption to supplying sprat to fishmeal plants.05 Theeffects of this change further down the food chain to bottom dwelling or pelagicspecies are still unknown for the Baltic Sea. There is also no information on how sealsand harbour porpoises, both already decimated in the Baltic Sea, are affected.Experience in other regions, however, should be a warning. In the Black Sea, forexample, excessive nutrient loads first led to a fishing boom in the 1970s, but ulti-mately, overfishing resulted in crashes in fish stocks, paving the way for burgeoningjellyfish populations that now dominate the system. These coelenterates feed on plank-ton and small fish larvae, making a return to the previous ecosystem state unlikely.06

© Solvin Zankl/Greenpeace© Sebastian Valanko/Greenpeace

6

Dwindling stocks

“ICES has advised low catches or a closure of the fishery for several years.The TAC [Total Allowable Catch] has been set well above the recommendedcatches.”07

The western Baltic cod stock is, compared to many others stocks of this species, still inrelatively good condition. However, as the stock has halved since the 1970s and 80s, it isstill considered by scientists to be close to the minimum “spawning stock biomass”.

ICES notes that stock replenishment is currently highly dependent on strong recruitmenteach year. Failing recruitment in just one year poses a severe threat to the fishery. ICEScalls, consequently, for a serious cut in catches for the year 2007, amounting to an almost30 % reduction compared to 2006. This should allow the stock to increase in size, andthus become less dependent on constant and strong recruitment rates.08

At the World Summits for Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro (1992) andJohannesburg (2002), the achievement of maximum sustainable yields was set as a targetfor all fisheries. The Baltic cod stock is considered overexploited by ICES, and musttherefore be restored to levels where it can provide a maximum sustainable yield.

The eastern Baltic cod stock has been hit much harder. It has been reduced to only a tenthof its size during the ‘Golden Ages’ of Baltic cod fishing in the 1980s.09 ICES suggests thatthis is the result of “increased effort in the traditional bottom trawl fishery, introduction ofa gillnet fishery, and decreased egg survival due to oxygen depletion of deep water layers.”10

ICES further reports a reduced reproductive capacity of the stock and regards the stock tobe harvested unsustainably. Given, that it is close to impossible to improve the environmentalconditions for cod recruitment, e.g., oxygenation of the water, ICES does not expectimprovements in the stock levels.11

For 2007, ICES has recommended that “no catch should be taken from this stock in2007 and a recovery plan should be developed and implemented as a prerequisite toreopening the fishery. ”12

In doing so, ICES has sent a stern warning to fisheries managers. Whether this warningwill be heard remains to be seen, however.

© Christian Åslund/Greenpeace© Christian Åslund/Greenpeace

7

Graph 1: ICES advice (red columns) on total allowable catch quota (TAC), quota agreed to by the EU (blue columns)and the spawing stock biomass (continuous curve) for cod in the Eastern Baltic Sea.13 Note: Where there is no column for ICES advice, ICES gave no recommendation or recommended a zero quota. Where there is no column for agreed quota, no data are available.

Graph 1Graph 1

Past experience does not bode well. As can be seen in Graph 1, in setting the total allow-able catch (TAC) for Baltic cod, EU Member States ignored ICES advice in every singleyear over an almost 20-year period. In each instance, the states set the actual TAC wellabove ICES recommendations. For 2006, for instance, the TAC was set at more than 3 times above the ICES recommendation: 49,220 t instead of 14,900 t.14 Perhaps mostimportantly, ICES recommended a complete cessation of fishing for cod in four of the past13 years, advice that was always ignored by the EU Member States.

For the western Baltic cod stock, the EU generally followed ICES advice, presumablybecause the recommended catch limits do not require drastic quota cuts or reductions inthe fleet that exploits this stock. In case of the eastern stock, on the other hand, the poormanagement and, consequently, high quota setting seems to be the result of a politicalunwillingness to address overcapacity in the fleet. Although the ‘Golden Age of Cod ’(1980s), when as much as 390,000 tons were taken annually, is long over, the fleet didnot yet adapt to the now much lower catch volume.

In July 2006, the European Commission presented a EU cod fishery “multi-annual management plan”15 aimed at rebuilding Baltic cod stocks, with 10 % annual reductionsin fishing effort and mortality.16 Specific rules further described how the fishing effortadjustments are to be made, and how scientific information will be used in setting totalallowable catches that correspond to the effort limits.It is questionable whether the slow, step-wise reductions in fishing mortality (10 % peryear) will be sufficient to address the looming crises for Baltic cod stocks. Any quota system further bears the risk of increased discard rates, with fishermen keeping only the largest cod on board and throwing smaller-sized or otherwise less profitable fish overboard, thus reserving their allocated quota for better yields.

Another significant problem for the protection and effective management of Baltic cod isthe high level of illegal fishing and lack of effective enforcement of existing rules. In particular, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) on cod in the easternBaltic is a significant problem. Reduced quotas bear the risk of only increasing the shareof such IUU fishing.

In its report on serious infringements of CFP (Common Fishery Policy) rules in 2004, the European Commission acknowledges that illegal fishing is a major problem, not leastin the Baltic cod fisheries.17 However, the Commission gives no indication how to improveenforcement in the EU Member States.

8

The fishing fleets

The Baltic cod fishery involves only a rather small number of nations. While Denmark (53 %in 2005) and Germany (32 %) share the bulk of the catch in the western waters, Poland(21 %), Sweden (14 %) and Denmark (13 %) dominate in the eastern Baltic Sea (Graph 2).

Graph 2: Landings of cod in the Baltic Sea by region and country in 200518

Graph 2:

For the eastern area, ICES assumes large volumes of so-called “unallocated” landings(14,991 tons in 2005), i.e. catches that are not registered officially, i.e. are unreported(Table 1). These tonnages fall into the category of “Illegal, Unreported, Unregulated” orIUU catches, and added 38 % to the offical landings (40,000 tons) in this part of theBaltic Sea. Most of these catches, insiders will admit, are believed to end up in Poland.

Table 1: Landings of cod in the Baltic by region and country in 200519

Baltic Sea Western Baltic Eastern Baltic22-32 22-24 25-32tons % tons % tons %

Denmark 19,039 30.7 11,769 53.4 7,270 18.2Poland 12,762 20.6 1,093 5.0 11,669 29.1Germany 9,341 15.0 7,002 31.8 2,339 5.8Sweden 9,295 15.0 1,555 7.1 7,740 19.3Latvia 3,989 6.4 476,000 2.1 3,513 8.8Russia 3,411 5.5 – – 3,411 8.5Lithuania 2,988 4.8 – – 2,988 7.5Estonia 972,000 1.6 139,000 0.6 833,000 2.1Finland 280,000 0.4 2,000 0.0 278,000 0.7Official Landings 62,077 100.0 22,036 100.0 40,041 100.0IUU 15,000 24.2 9,000 0.0 14,991 37.4Total Landings 77,077 124.2 22,045 100.0 55,032 137.4

Vessels fishing for cod range from small boats of some few metres in length to large trawlersof up to 40 m. Most catches are taken by vessels around 17-30 metres. The largest fleet isoperated by Poland, which authorized 663 vessels to fish for Baltic cod in 2006. Only 93 out of the 663 vessels exceeded 24 metres. The situation is similar in Denmarkwith 483 vessels registered, but only 4 over 24 metres, Germany with 364 vessels and 20 vessels over 24 metres and Sweden with 330 vessels and 19 over 24 metres. Most ofthese vessels are privately owned, but united in regional associations in charge of distrib-uting the national quota to the individual vessels and of jointly marketing the catch of theassociated fleet.Gillnets and trawls are used for cod fishing. In 2004, 48 % of the cod in the easternBaltic was caught by trawlers, the remainder by gillnets.20

9

Pirate fishing in the Baltic

In 2005, ICES estimated the true catchesof cod in the eastern Baltic Sea to bemore than 38 % above the officiallyrecorded landings of around 40,000 t(Graph 3). These are catches that werenot reported to the authorities and henceare missing from the official landing statistics. A peak was reached in 2003,when as much as 45 % above the officiallandings were taken illegally.21 Polishscientists paint an even darker picture,assuming illegal catches of 100 % abovethe quota.22 The illegal catch is a heavyburden on an already depleted stock andrenders it almost impossible for fisheriesscientists to produce reasonable stockestimates.

Illegal Fishing and Poland

In nearly all fisheries that have a restricted quota, where controls are not tight and pun-ishment does not work as a deterrent, exceeding the allocation seems common. With clearinformation scarce (for obvious reasons), illegal cod landings are likely to be common inall Baltic countries. In 2001, for instance, the Danish fish processing company Espersenwas caught using cod fished illegally in the Baltic Sea. The company was fined € 134,000.Espersen was caught again red handed in early 2006, this time receiving illegal cod fromthe Barents Sea. In the latter case, Espersen claimed to have been ignorant of the trueorigin of the cod, and it was not charged.24

In 2006, ICES “Baltic Fisheries Assessments Working Group” listed 3 different, country-specific factors for converting official landings into actual landings, ranging from 1 (noillegal catches), to 1.5 and 2 (illegal catches of half or the same volume as legal catches).ICES did not indicate which factors were to be used for which country, but clearly indicatedthrough its very detailed proceedings that illegal, unreported catches are not restricted tojust one country, but are widespread across the region.25

According to many stakeholders in the fisheries sector, the worst offenders are to be foundin Poland. The huge fleet has reacted badly to its reduced legally allocated quota, respond-ing with illegal fishing.

Graph 3: Unreported vs. official landings inthe Eastern Baltic in 2005, ICES estimate23

© Thomas Haentzschel/nordlicht/Greenpeace

10

These unofficial claims are strongly supported by official statistics (Table 2). In 2005,Poland had cod landings of 12,762 tons, all taken in the Baltic.26 These catches were supplemented by imports of cod amounting to 22,772 tons27 (converted to catch weight).28

Poland’s catches and imports resulted in a total of 39,522 tons of cod available for pro-cessing, export and domestic consumption. Exports of cod products, however, amounted to 48,015 tons, leaving Poland with a supplygap of 8,493 tons or 19 % of the total official catches in the eastern Baltic Sea, Poland’ssole fishing area for cod.

Table 2: Trade balance for cod in selected EU Baltic countries29

Domestic Landings Imports Exports Surplus/Gap Estimated Surplus/Gapdomestic, excl. domestic

consumption consumption

Poland 12,762 26,760 48,015 -8,493 9,634 -18,127

Germany 13,605 74,021 35,596 52,031 25,345 26,686

Denmark 43,301 193,943 231,524 5,719 3,161 2,558

Sweden 10,000 122,558 109,832 22,725 6,244 16,481

This calculation does not include domestic consumption of cod. Unfortunately, there are noofficial figures on fish consumption by species for Poland. According to Eurostat, totalconsumption of fish in Poland was 9.9 kg per person in 200130. Assuming the same shareof cod as in Germany (2.5 %), Poland’s total domestic cod consumption may have beenaround 9,630 tons in that year.

Poland’s supply gap may thus jump to over 18,000 tons, or 45 % of the total official catchin the Eastern Baltic.

These estimates for illegal activities in Poland may account for a large part of what ICESpresented as unreported landings in 2005 (14,991 tons), or even exceed it. In Poland, theseillegal catches are combined with legal supplies and cannot be recognised on the consumermarketplace. Poland has become a major country for cod processing, exporting hugeamounts of mainly frozen fillets to western markets (led by the UK, Germany, Denmarkand Belgium). But even the US receives significant amounts reaching to over 1,000 tonsin 2005.

The figures above could well be an underestimate as it is unlikely, that Poland is the onlyoffender. Even ICES ‘daring’ estimates of 38 % unallocated (illegal) landings, may be toolow.

© Christian Åslund/Greenpeace

© Konrad Konstantynowicz/Greenpeace

11

Enforcement is a slap on the wrist

Fisheries management continues to suffer from a lack of control and enforcement, allow-ing for large amounts of illegal catches. Even when perpetrators are exposed, penaltiesare generally too small to deter the offenders. This has been recognised as a problem, notleast in the European Commission’s 2006 Report on the level of non-compliance in EUfisheries:

“… most of the penalties imposed on offenders are clearly insufficient to havea real deterrent effect.” (European Report on Serious Infringements under the CFP, July 2006)

Even though the European Community’s Common Fisheries Policy requires EU MemberStates to supply detailed information about their fishing vessels and other aspects of fish-eries management, this information is often supplied late or not at all. For instance, thereis an obligation to monitor and report catches, but the Commission notes that only “threeMember States – Denmark, Sweden and the UK – complied fully with the rules by submit-ting all the required catch reports on time, while three others – Cyprus, Malta and Slovenia– failed to submit any reports at all”31. Moreover, only 10 of the 20 coastal EU MemberStates transmitted their regular monthly reports on catches within the established dead-lines, and the submission of quarterly reports continued to be unsatisfactory in terms ofoverall response. Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Lithuania, Malta and Slovenia failed to submit anyquarterly reports. According to the European Commission, fishing effort declarations in2004 regressed compared to 2003. Only two EU Member States (Belgium and Sweden)met their obligations on fishing effort declarations in 2004.

The Commission further summarises that “[the] number of serious infringements detectedand reported to the Commission rose to 9,502 in 2003, compared to 6,756 in 2002. As inprevious years, the commonest form of serious infringement was “unauthorised fishing”.Importantly, the Commission concludes that “the level of fines being applied across theCommunity for wrong-doings in the fisheries sector is not acting as a deterrent and, basi-cally, more needs to be done to deter lawbreakers”. In fact, penalties imposed by MemberStates accounted for only 0.2 % of the landing value in 2003 and may simply be consid-ered as part of the running costs by the industry. The Commission further noted, that thesituation is worsening, with the average level of fines halving between 2003 and 2004.32

The report calls for stronger application of drastic measures, such as the suspension offishing licenses, noting that few Member States actually use this tool.

The Baltic Sea states, despite the obvious problem of large scale illegal fishing on cod, areamongst those with the weakest law enforcement and lowest penalties. In 2004, for example,only Denmark and Germany withdrew fishing licences in a limited number of cases, whilePoland and Sweden reported no such cases to the Commission. The average fine imposedby these 4 countries ranged between € 375 and € 538 per infringement, while theEuropean-wide average was at € 2,272.

The UK, for example, regards falsifying or failing to record data in logbooks as a seriousbreach of regulations, imposing a fine of € 18,900 on average. It did so in 59 cases. Theaverage fines imposed in Germany (€ 97), Denmark (€ 307), Sweden (€ 593) and Poland(€ 401), by contrast, suggest a very lax attitude towards one of the main methods of concealing illegal catches.

12

Baltic cod travel far on land

Most of the cod caught in the Baltic Sea is landed in Denmark, Poland, Germany andSweden. Poland, Sweden and Denmark dominate the larger eastern landings, andGermany and Denmark dominate in the west. Little of the cod is consumed where it islanded, however. Sweden and Germany export a large part of their cod catches, with Denmark, theNetherlands and France being the major destinations.33 In 2005, Germany exported 7,400 tons34 of whole cod, equivalent to 80 % of its whole cod catch.35 Sweden exportedeven more whole cod than its own fishery had landed, due to larger imports of fresh codfrom Norway. In both countries, industrial capacities for filleting fresh cod are small thesedays. Decreasing catches by home fleets have destroyed this industry sector, and cod isnow being shipped to neighbouring countries for the first processing step (filleting). Inrecent years, Poland has emerged as an important cod processing country, supplementingits own large catches in the Eastern Baltic with imports of over 23,000 t (catch weight)of whole fresh or frozen cod,36 mainly from Russia and Denmark. In turn, Poland suppliedover 41,000 t (catch weight) of cod filets to Western Europe, with the UK taking the bulk(44 %), followed by France (15 %), Germany (13 %), Denmark (12 %) and Belgium (9 %).37

Cod from illegal fishing, landed and processed in Poland thus reaches most of the majorEuropean markets for cod products.

Chart showing major destinations of cod caught in the Baltic and major exports andimports of unprocessed and semi-processed cod likely to originate from the BalticNote: Most countries either fish on cod also in areas outside the Baltic and/or import from there. These flows have not been included here.

(figure 2)

13

Denmark has a raw material supplier role somewhat intermediate between those ofSweden and Germany on the one hand and Poland on the other. Denmark imports andexports large amounts of whole cod, but retains enough to be a major producer andexporter of fillets to countries such as the UK (22 %), France (21 %), Germany (14 %)and Italy (12 %).38

Amongst the four major nations cod fishing in the Baltic Sea, Germany has by far thelargest domestic consumption. This consumption, however, also includes cod originatingfrom areas outside the Baltic Sea and includes fish further processed into convenienceproducts also for exports such as battered cod fillets, fish burger, fish finger etc.. Three of the major international companies producing deep frozen fish products are locatedin Germany. German factories of Unilever (Iglo), Frosta and Pickenpack supply the wholeEuropean market. Deep frozen convenience products, however, have lost their importancefor the cod fishery in recent times. The success story of the ‘fish finger’ was based for along time solely on North Atlantic cod. With fierce price competition in this sector, and ageneral scarcity of cod leading to higher prices, cod can no longer compete with cheapersubstitutes from the Northern Pacific Ocean (Alaska Pollack), Chile (hake) or New Zealand(Hoki). Cod today remains available mainly as natural or battered deep-frozen fillets inthis market sector. Several companies such Pickenpack and Frosta (Germany), Fjord Seafood (Netherlands), Västkustfilé (Sweden) and Royal Greenland (Denmark) supply fillets from Baltic catches.

Most cod caught in the Baltic is now sold as fresh whole fish or fillets, either retail, ordirectly to restaurants. One notable exception remains, however. Espersen A/S of Denmark,one of Europe’s largest processors of fish for the deep frozen convenience market, claimsto use up to 25 % of the total annual catch of Baltic cod.39 The Baltic and Barents codprocessed by Espersen is sold in supermarkets, for example as fish finger under the COOPbrand “Xtra”, the “Euroshopper” brand of ICA (Sweden) and Kesko (Finland), and the“Rainbow” brand in Finland.40 Through Espersen, McDonald's Europe41 receives Baltic cod,besides cod from the Barents Sea and Hoki from New Zealand for their “FishMäc®” or“Filet-O-Fish®” sandwich.

With a turnover of over € 130 million Espersen is regarded as the largest cod processingcompany in the world.42 Originally founded on Bornholm, Germany, Espersen startedrecently to produce cod fillets in Klaipeda (Lithuania) and Koszalin (Poland). Thus it canprofit from cheaper production costs and easy access to these countries’ cod quotas. Other international giants of fish processing have discovered Poland as a location for theirbusiness, including Royal Greenland and Frosta. Both companies have Baltic cod in theirfrozen fish product range.43

© Peter Dammann/Greenpeace© Peter Dammann/Greenpeace

14

The political level

Since the enlargement of the European Union (EU), most of the Baltic Sea is governed bythe Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) of the European Community. Under the CFP, fisheriesmanagement is under the exclusive control of the Community, which must regulate fishingactivities through joint decision-making in the Council of Ministers or through the admin-istrative powers of the European Commission.

Fisheries management in the territorial or inshore waters of EU Member States are anexception to this rule. For the inshore zone, some powers to control fishing have been delegated back to the Member States.

The CFP sets out detailed management measures, including access conditions, as well ascontrol and enforcement rules relating to fisheries. It includes explicit reference to theprecautionary principle and the ecosystem-based approach, with its main objective beingthe sustainable exploitation of living aquatic resources, conservation and the minimisationof fishing activity impact on marine ecosystems. For the Baltic Sea, a number of technicalmeasures affecting the cod fisheries are in force. These measures include closed areas/seasonsto limit fishing effort, and gear-specific measures to enhance selectivity in the fisheries. In the Commission’s own words, “[these] technical measures have, however, not been sufficient to address the problem of unsustainable fishing levels”.44

The stock data presented in this report, however, suggests that the CFP has consistentlyfailed to conserve target fish stocks (in this case, Baltic cod) and prevent their collapse.The CFP’s failure to prevent the imminent collapse of Baltic cod stocks, however, is basedmainly on the lack of political willingness to agree on drastic quota cuts and lack of effective quota enforcement, rather than a lack of rules. In particular, the failure of theCouncil of Ministers to act according to the strong and clear scientific advice from ICESand others has had dire consequences for Baltic cod stocks.

By 2001, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) had adopted anInternational Plan of Action to combat Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing(IPOA-IUU), essentially a voluntary pledge of commitment to tackle IUU fishing. At the World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002, world leaders, including thosefrom the European Community, made a commitment to implement the IPOA-IUU andeliminate IUU fishing by 2004. In the same year, the European Commission adopted theCommunity’s Action Plan for the eradication of IUU fishing (COM(2002)180), listing 15 ‘new’ areas of action which would require Community attention. In 2003, the group ofthe eight most developed countries45 made a commitment to urgently develop and implementthe IPOA-IUU. In March 2005, Fisheries Ministers reaffirmed their commitment to eliminate IUU fishing in the context of the Committee on Fisheries of the FAO.46

Despite this high-level attention, little, if any, effective measures have been taken to eliminate IUU fishing. Too often, the European Community, through its Member States, is implicated in the activities of pirate fishers.

A newly proposed EU Marine Directive (COM(2005)505) also misses the opportunity toensure better protection for the sea from unsustainable and illegal fishing, and will notprotect dwindling populations of species that are exploited through fishing, unless changesto the proposed law are made.

15

Only an immediate cessation of the cod fishery in the eastern Baltic Sea in line with thescientific advice given by ICES may give the Baltic cod stock a chance to recover.

To prohibit illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, the European Union and the MemberStates should establish a central monitoring, control and compliance authority at sea and onland, including a transparent and mandatory vessel monitoring system for all active vessels.Furthermore, all ports must ensure, through thorough inspection and verification with relevant authorities, that the fish being landed is legally caught, before accepting cargo.

Beside overfishing, both legal and illegal, all life in the Baltic is further threatened byeutrophication, toxic contamination, introduction of alien species and sand and gravelextraction. In addition, the rise in shipping and oil transportation has increased the likelihood of a major maritime disaster.

The precarious situation of the Baltic marine environment requires urgent and collectiveaction to restore and protect marine life. Marine reserves are a proven and accepted conservation tool, providing full protection for the entire spectrum of species, habitatand ecosystem diversity, allowing the sea to ‘catch its breath’ and recover a self sufficientecosystem balance. The reserves can also provide additional benefits for fisheries, recre-ation and science. Reserves are also much easier to monitor for illegal activities than thecurrent patchwork of rules with large differences between member states.

The European Marine Strategy, and the associated proposed EU Directive for the protec-tion of the marine environment, could deliver a mechanism by which large-scale marinereserves will be established in the Baltic Sea. Furthermore, it would, for the first time,provide a coherent policy for the protection of the Baltic Sea, together with sustainableresource management.

It is now up to the governments of EU member states to make the most of this opportunity,by moving beyond the sectoral approach, by putting the health of the marine environmentand by placing Europe’s citizens at the centre of decision making. Now is the time todeliver on political promises - to make a network of large-scale marine reserves a realityin the Baltic Sea.

Conclusions and Demands© Christian Åslund/Greenpeace

Greenpeace International, Ottho Heldringsstraat 5, 1066 AZ Amsterdam,The Netherlandspublished by Dr. Iris Menn, September 2006

T +31 20 718 2000, F +31 20 514 8151 www.greenpeace.org

Contacts:Greenpeace Sweden, Hökens gata 2, Box 151 64, 104 65 Stockholm, SwedenT +46 8 702 70 70, F +46-8-694 9013, e-mail: [email protected]

Greenpeace Denmark, Bredgade 20, 1260 Cobenhagen K., Denmark T +45 33 93 86 60, F +45 33 93 53 99, e-mail: [email protected]

Greenpeace Poland, ul. Pluga 3 m. 15, 02-047 Warszawa, PolandT/F +48 22 659 94 18, e-mail: [email protected]

Greenpeace Germany, Große Elbstrasse 39, 22767 Hamburg, GermanyT +49 40 30618 0, F +49 40 30618 100, email: [email protected]

Design: www.nicolepostdesign.nl

01 For a history of cod fishing see: Mark Kurlansky, Cod. A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World, 1997. Walker & Company, New York

02 PROTECT, Review of MPAs for Ecosystem Conservation & Fisheries Management, February 2006

03 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod (chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)

04 l Merentutkimuslaitos, Finnish Institute of Marine Research (http://www.fimr.fi/fi/aranda/uutiset/233.html)

05 for more information see, e.g.: PROTECT, Review of MPAs for Ecosystem Conservation & Fisheries Management, February 2006

06 see e.g., FAO, 2003, The ecosystem approach to fisheries (http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/Y4773E/y4773e06.htm)

07 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod (chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)

08 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod (chapter 8.4.1. Cod in Subdivisions 22-24)

09 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod (chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)

10 ICES, 2005 Baltic Fisheries Assessment Working Group, Cod11 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod

(chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)12 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod

(chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)13 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod

(chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)14 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod

(chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)15 Proposal for a COUNCIL REGULATION, Establishing a

multi-annual plan for the cod stocks in the Baltic Sea and the fisheries exploiting those stocks, presented by the Commission, July 24th 2006, COM(2006) 411 final

16 Commission proposes multi-annual plan to rebuild Baltic cod stocks, EU Press Release IP/06/1055, July 24 2006

17 EU Commission, July 2006, Reports from Member States on behaviours which seriously infringed the rules of theCommon Fisheries Policy in 2004, COM(2006) 387 final

18 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Western and Eastern Baltic cod(chapter 8.4.1 and 8.4.2.)

19 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Western and Eastern Baltic cod(chapter 8.4.1 and 8.4.2.)

20 ICES WGFAS 2005, chapter 2 Cod, p16921 ICES, May 2006, Advice on Eastern Baltic Cod

(chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)22 Morski Instytut Rybacki w Gdyni, “Czy wiemy ile jest dorszy

w Baltyku”, http://www.mir.gdynia.pl./artykuly/ile_dorsza.php

23 ICES, May 2006, Advice on Eastern Baltic Cod (chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)

24 www.dr.dk, 22/08/05 Danish national tv homepage25 ICES, Baltic Fisheries Assessments Working Group,

Report 200626 ICES, May 2006, Advise on Eastern Baltic Cod

(chapter 8.4.2. Cod in Subdivisions 25-32)27 Eurostat28 figures were converted into catch weight based on

conversion figures, supplied by the Bundesanstalt für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft of Germany, taken from „Das Kabeljau-Dilemma”, WWF, January 2002

29 based on Eurostat trade and ICES catch statistics30 Zahlen und Fakten über die GFP, Ausgabe 2006.

Eurostat 200631 European Commission Press Release on the Fisheries

Compliance Scoreboard http://europa.eu.int/comm/fisheries/news_corner/press/inf06_04_en.htm 19.01.06

32 Commission: stricter sanctions are needed to deter infringements to fisheries rules, EU Commission Press Release, 2006-07-

33 In 2005, Sweden exported 8,259 tons of whole cod, while its total catch amounted to 10,000 t. Sweden also imported 6,624 tons of whole cod, mainly from Norway.

34 coverted to catch weight35 German trawlers landed also cod filets, which are excluded

from this calculation, that compares whole cod catches and exports only

36 coverted to catch weight37 Eurostat38 Eurostat39 “Fish Burgers are Fresh Fish from Denmark”, Focus

Denmark, Danish Trade Council, Ministry of Foreign Affairs,June 2002see also: Fiskebranchen frygter ny nedskaering af torske-kvote, Dagbladet Borsen, September 7, 2004

40 Greenpeace research41 For Icelandic, a tale of two U.K. subsidiaries, Intrafish,

March 20 2006 (http://www.intrafish.no/global/news/article102914.ece)

42 Oestersoe-regionen som hjemmebane, Dagbladet Borsen, September 16 2002

43 Greenpeace research, 200644 proposed Baltic Cod Multi-Annual Management Plan

(COM(2006)411)45 USA, Russia, UK, France, Italy, Canada, Japan, Germany46 http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2005/100200/

Bibliography

![Overfishing karina nina_ivoslav_10-7[1]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/554c1892b4c905f1518b4fa8/overfishing-karina-ninaivoslav10-71.jpg)