ˆˇ˘ ˚˛ ˘ ˛ ˆˆˇ˘˛ - Boston Society of Architects · sets the record straight....

Transcript of ˆˇ˘ ˚˛ ˘ ˛ ˆˆˇ˘˛ - Boston Society of Architects · sets the record straight....

Comments on the Previous Issue LETTERS

Fall 2013 7

On “American Gropius” (Summer 2013)

CANAM30139_ArchitectureBostonCorpoAN_A01.indd8,5” x 11”4C

DATA:LIVE:Studio_MTL:CANAM:30139_Annonces supplementaires (nov. 2012 - ...):PRODUCTION:30139_ArchitectureBostonCorpoAN_A01.indd

Paul (227)Olivier (240)Dimitri (236)Rafik (232)

A0131/01/13 à 11:16

At Canam, this is how we operate.Over the last 50 years we have developed a fast, reliable construction method that adapts to all your commercial, industrial, institutional or multi-residential projects. Whether you are building structures, floors, walls or steel building envelopes, our construction solutions are simple and straightforward. So you don’t get any surprises.

1-800-926-5926 canam-construction.com

Your construction site. No hassles. No worries. No surprises. Imagine that…

The “American Gropius” issue was extraordinary in its content and format. Never before have I seen so many aspects of Walter Gropius’ life celebrated in one publication.

We at The Architects Collaborative (TAC) knew Grope as a man of great design insight and a philosopher in his own right — but also as an architect who faced the same design challenges we all struggled with. We honored his past achievements, trusted his judgment, and were more than slightly awed by his presence in the firm. He was our colleague and fellow collaborator, as well as our friend, with shared objectives for modern design.

When I joined TAC, Grope was already in his early 80s, but he made his presence felt. I recall one instance when he questioned the elevations of a hospital project we were doing in Minnesota. He wondered why the building façades were all the same and didn’t reflect different solar-orientation requirements. I gave him a rather lame answer, but since that day I have always tried to make my buildings more responsive to climate and natural conditions.

We all cherish the accomplishments of Walter Gropius and are grateful to ArchitectureBoston for presenting the man in three dimensions.

perry king neubauer faiaTAC president, 1989–93 Cambridge, Massachusetts

The mix of essays in “American Gropius” is well chosen to demystify this central individual, who is often misinterpreted. They usefully open up an examination of the Silver Fox and what he did and did not achieve. Conspicuously absent from the list of topics — Gropius as founder, mentor, scientist, social theorist, teacher, and product designer — is a consideration of Gropius as architect. But the quotation from Sally Harkness, “Everyone wants to

think of him as one of the world’s great architects; he wasn’t. He was one of the world’s great philosophers,” succinctly sets the record straight. Nevertheless, the exquisite photo essay on the Gropius-chosen objects for his house in Lincoln, and the commentary by the engineers responsible for the restoration of that building, show that the finest example of Gropius’ work as an architect in the United States is available to us all, through the stewardship of Historic New England.

keith n. morganDirector of Architectural Studies, Boston University Boston

Near the start of “A Man of Parts,” we have the introduction of the term Modernism (in the title of a book by professor Anthony Alofsin). Grope had no use for this form of labeling. He happily corrected people who insisted that he taught “the International Style” saying, “The International Style is all of the Greek temples spread throughout the world.” Alofsin’s simplification is fostered by some strange need to paste one more “-ism” onto the argot of architecture.

My thanks to Bob Campbell, my successor as architecture critic at The Boston Globe. His experience at Harvard has given us an understanding of Josep Lluís Sert at a time when the Graduate School of Design was going through perfectly normal changes and modifications. His article does not hide behind those “-isms” that infect discussion of what is a socially, historically, technically, environmentally, and artistically rational process.

David Fixler’s pages start out with my standard disqualifier: semantics. I recommend [the philosopher] Alfred Korzybski to all who wonder why high-order abstractions like “Modernism” are blissfully impotent. David is correct in challenging the word and suggesting that

it can have extended meanings. But I had three courses with GSD dean Joe Hudnut and never once heard him suggest that there was something called “the Modernist Movement.”

Grope did not teach “Modern architecture” or “Modernism” or anything but common sense. By asking us first to solve all of the

“problems” of the design program, usually with useful options, the concept of “art” can naturally evolve. Although this may ask for program adjustments, it ensures that the higher-order abstractions such as looks, feelings, fears, community, environment, history, and cost can come into play when they will be more productive. He taught us what it was to be an architect, not an “-ist” of any kind.

joseph l. eldredge faiaWest Tisbury, Massachusetts

Michael Kubo’s excellent article, “The Cambridge School,” inspired me to recall what made TAC so special in my 20 years with the team.

Personal: TAC was my first large office experience after arriving in the post-Gropius era in 1970. My family and I lived at 60 Brattle Street, so I fell out of bed into the office and lived in the so-called “Architects’ Corner” 24 hours a day. Our sons, Chris and Jon, would sometimes drop by to draw on a nearby board, reinforcing John Sheehy’s comments about TAC being a “way of life.” TAC always encouraged its members to teach when possible, which reinforced the linkage between real-life practice and academia in which TAC was rooted.

Collaboration: There was a great deal of individual identity and competition within the collaborative process, but the final result was a TAC effort. I recall a moment in one of the design reviews when a talented young GSD student was referring to “my idea, my thinking,” when suddenly Louis McMillen interjected,

LETTERS Comments on the Previous Issue

8 ArchitectureBoston

ArchitectureBoston Volume 16: Number 3

®

saying, “Son, it is TAC’s scheme.” The rest of his presentation after this learning moment was a bit more humble.

Learning Lab: Open offices allowed people to interact and even overhear phone conversations. We could hear Howard Elkus talking with the developer on the Copley Place project about the magic of the interactive day-lit public spaces, as well as the functional net rentable spaces; Joe Hoskins engaging Bill LeMessurier about the size of the beam of the 37.5-foot cantilever off of the 3-4-5 triangular bay of our Johns Manville World Headquarters building outside Denver (while we were listening to

“Rocky Mountain High” in the background); and the many nearby team meetings talking about energy and accessibility issues. We learned from the dialogue among engineers, clients, and vendors in open, interactive learning. It is quite different from today’s plugged-in, quiet offices.

The workday hardly ever ended at 5 pm, as we all worked nights at the Casablanca, Ha’Penny, Harvest, Blue Parrot, and Idler on napkins, tablecloths, and menus, returning to the studios to work until dawn. The drawings finally ended up at Charrette for Bob Beal to oversee the printing, after which we carted them off to Denver, Kuwait, or downtown Boston.

michael francis gebhart faiaMichael F. Gebhart Architects Cambridge, Massachusetts

I worked at The Architects Collaborative as assistant librarian from 1967–68 and saw Gropius almost every day. When I arrived at TAC’s new office building on Brattle Street, I did not really know what a special place it was. I became interested in architecture only during my senior year in college and wanted to learn more about it. What an extraordinary way to start!

The opportunity to “work” with Gropius came when TAC was assembling an art installation for one of its office buildings. I was brought along to take notes as Gropius and the architectural staff visited a private collection in the Back Bay. As we entered the very upscale residence, it was Gropius who took my coat. He was a gentleman in the true meaning of the word, a man respectful

and considerate of those around him.He was also very respectful of women.

Two of TAC’s original seven partners were women, which was highly unusual for the time. I have to thank Gropius for my believing I, too, could be an architect.

nancy goodwin aiaFinegold Alexander + Associates Boston

Gordon Bruce’s article, “A Total Theory of Design,” is a well-constructed summary of his book on Eliot Noyes. His multiple years as a design professional at Noyes’ studio in New Canaan, Connecticut, followed by success in his own firm, give him credence. It is fair to say that, besides Harley Earl’s orchestration of General Motors’ first design departments, Eliot Noyes’ leadership at IBM was one of the first formally organized American corporate product-design and branding studios.

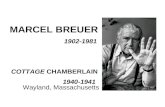

While Earl’s influence on American design and manufacturing was a combination of a self-taught and incomplete traditional engineering education, Noyes was fortunate to be educated by masters such as Gropius and Marcel Breuer, and was influenced by Harvard’s New Bauhaus training. Like Earl, what Noyes did better than others was translate his (often esoteric) academic experience into tangible and successful products that the user can actively engage with.

My enjoyment of Bruce’s article leads to this question: How can historical design-management education from the likes of Noyes and Earl be reintroduced to contem-porary students of design? From my daily interaction with young designers, it appears their knowledge of design history is limited. Few have any frame of reference further back than Apple and Jonathan Ive/Steve Jobs.

Communicating “how it has been done successfully before” to young professionals is often a grizzly and boring task. But the design- and business-management knowledge in this area is potentially most powerful in the hands of up-and-coming innovators.

We aficionados tend to spend too much time reminiscing on the past. While I am not a formal educator, we need new ways, contemporary and meaningful, to

www.architectureboston.com

EDITOR

Renée Loth · [email protected]

DEPUTY EDITOR

Fiona Luis · [email protected]

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Virginia Quinn · [email protected] Baker · [email protected]

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Steve Rosenthal, Peter Vanderwarker

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Conor MacDonald

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Matthew Bronski pe, Duo Dickinson aia, Shauna Gillies-Smith, Matthew Kiefer, David Luberoff, Hubert Murray faia

EDITORIAL BOARD

Ian Baldwin, Steven Brittan assoc. aia, Steven Cecil aia, Sho-Ping Chin faia, David Gamble aia, Diane Georgopulos faia, Chris Grimley, Dan Hisel, Mikyoung Kim, Drew Leff, Patrick McCafferty pe, Anthony Piermarini aia, Kelly Sherman, Marie Sorensen aia, Julie Michaels Spence, Pratap Talwar, Frano Violich faia, Jay Wickersham faia

ART DIRECTION, DESIGN, AND PRODUCTION

Clifford Stoltze, Stoltze Design · www.stoltze.comKatherine Hughes, Kyle Nelson, Joanna Boyle

PUBLISHER

Pamela de Oliveira-Smith · [email protected]

ADVERTISING

John Allen, Steve Headly, Brian Keefe, Steve Orth 800.996.3863 · [email protected]

BOSTON SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTS

Mike Davis faia, President Emily Grandstaff-Rice aia, Vice President James H. Collins, Jr., faia, Treasurer Hansy Better Barraza aia, Secretary

290 Congress Street, Suite 200, Boston, MA 02110 617.391.4000 · www.architects.org

ArchitectureBoston is mailed to members of the Boston Society of Architects and the American Institute of Architects in New England. Subscription rate for others is $26 per year. Call 617.391.4000 or e-mail [email protected].

ArchitectureBoston is published by the Boston Society of Architects. © 2013 The Boston Society of Architects. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited.

ArchitectureBoston invites story ideas that connect architecture to social, cultural, political, and economic trends. Editorial guidelines are available at www.architectureboston.com. Unsolicited materials will not be returned. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the editorial staff, the Boston Society of Architects, or Stoltze Design.

postmaster: changes of address to ArchitectureBoston, 290 Congress Street, Suite 200, Boston, MA 02110

issn 1099-6346 PLEASE RECYCLE THIS MAGAZINE

Fall 2013 9

communicate this information to those outside the “history buff” circuit. Any takers?

todd ellisPUMA Boston

Your “American Gropius” issue not only showed Gropius as an important teacher, as an architect, and as a thinker, but above all as a real person who was also a humanist. The issue should be required reading for all aspiring architects and designers.

Design Research (DR), the retail store founded by Ben Thompson [of TAC], was mentioned. But perhaps it should have gone a step further to give credit to DR’s leadership in introducing good design in ordinary products to the whole country — yet another achievement inspired by Walter Gropius.

arnold friedmannUniversity of Massachusetts/Amherst Amherst, Massachusetts

Having spent 25 happy years at The Architects Collaborative, I found all of the “American Gropius” articles to be credible, thoughtful, and profound. The issue reaffirms for me that Walter Gropius wanted to be a citizen of a totally inclusive great society. In his vision, architecture and technology were never the end point: they were the means for a better life for everyone. Did he succeed in his lifetime, and how did it all work out? Perhaps Gropius the philosopher gives us a clue in the following letter he sent to students in 1964:

“For whatever profession, your inner devotion to the tasks you have set yourself must be so deep that you can never be deflected from your aim. However often the thread may be torn out of your hands, you must develop enough patience to wind it up again and again. Act as if you were going to live forever and cast your plans way ahead. By this I mean that you must feel responsible without time limitation, and the consideration whether you may not be around to see the results should never enter

your thoughts. If your contribution has been vital, there will always be somebody to pick up where you left off, and that will be your claim to immortality.”

john p. sheehy faiaArchitecture International San Francisco

For more letters, visit architectureboston.com.

We want to hear from you. Letters may be sent

to [email protected] or mailed to

ArchitectureBoston, 290 Congress Street, Suite

200, Boston, MA 02110. Letters may be edited

for clarity and length, and must include your

name, address, and daytime telephone number.

Length should not exceed 300 words.

Correction: A photograph on page 36 of

the “American Gropius” issue carried an

inaccurate caption. It should have read “Hartford

(Connecticut) Jewish Community Center, corner

of the athletic wing.”

Comments on the Previous Issue LETTERS

we are wide format.

Canon MFP M40 SeriesCopy • Print • Color Scan System

6 “D”-size prints per minute Oce Plotwave 350

www.makepeace.com • (800) 835-0194 • [email protected]. MAKEPEACEsince 1895

WIDE FORMAT PLOT/COPY/SCAN SYSTEMSFACILITIES MANAGEMENT SERVICES

DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT AND ARCHIVING SOLUTIONS

HP T920 HP T1500NEW HP DesignJet ePrinter Series