© 2010 Daniela Roditi - ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu · 1 effects of coping statements on experimental...

Transcript of © 2010 Daniela Roditi - ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu · 1 effects of coping statements on experimental...

1

EFFECTS OF COPING STATEMENTS ON EXPERIMENTAL PAIN IN CHRONIC PAIN PATIENTS

By

DANIELA RODITI

A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT

OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

2010

2

© 2010 Daniela Roditi

3

To everyone who has inspired, encouraged, and supported me throughout my lifetime in all personal, academic, and professional achievements, making this milestone

possible

4

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am greatly thankful to my mentor, Dr. Michael E. Robinson, for his continuing and

unwavering support and guidance throughout the development of this project from the

beginning to the end. Additionally, I would like to recognize as the members of my

supervisory committee Dr. Stephen Boggs, Dr. Glenn Ashkanazi, and Dr. Russell

Bauer. Lastly, I would like to recognize my family, friends, and colleagues for their

support throughout this project.

5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

page

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4

LIST OF TABLES ..........................................................................................................................7

LIST OF FIGURES........................................................................................................................8

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................9

CHAPTER

1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................11

Coping 11 Catastrophizing .............................................................................................................11 Positive Coping Self-Statements ...............................................................................12

Response Expectancies .....................................................................................................12 Previous Coping Research ................................................................................................13 Current Study .......................................................................................................................14

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS ...........................................................................................15

Procedure ..............................................................................................................................15 Participants ...........................................................................................................................16 Apparatuses..........................................................................................................................17 Measures ..............................................................................................................................17

Demographics ...............................................................................................................17 Coping Statements .......................................................................................................18 Pain Threshold ..............................................................................................................18 Pain Tolerance ..............................................................................................................18 Pain Endurance .............................................................................................................18 Pain Intensity .................................................................................................................19

3 RESULTS ..............................................................................................................................24

Descriptive Analyses ...........................................................................................................24 First Hypothesis ....................................................................................................................24 Second Hypothesis ..............................................................................................................26

4 DISCUSSION .......................................................................................................................30

Clinical Implications .............................................................................................................34 Methodological Limitations and Future Research Directions .......................................35

6

5 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................38

LIST OF REFERENCES ............................................................................................................40

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ........................................................................................................44

7

LIST OF TABLES

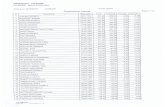

Table page 2-1 Demographic variables of total sample (N = 58) ................................................. 19

2-2 List of Catastrophizing Self-Statements .............................................................. 20

2-3 List of Positive Coping Self-Statements .............................................................. 21

3-1 ANOVA results of comparison between two coping groups ............................... 27

3-2 Mean PSR and Peak Pain Intensity Measurements of Catastrophizing and Positive Self-Statement (PSS) Groups ............................................................... 29

8

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure page 2-1 Experimental Procedure Flowchart ..................................................................... 22

2-2 Cold Pressor Apparatus. Taken in 2010 in the Center for Pain Research laboratory ........................................................................................................... 23

3-1 Effects of coping manipulation on PSR. ............................................................. 28

9

Abstract of Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science

EFFECTS OF COPING STATEMENTS IN EXPERIMENTAL PAIN IN CHRONIC PAIN

PATIENTS

By

Daniela Roditi

May 2010 Chair: Michael E. Robinson Major: Psychology

Catastrophizing has been well-established in the literature as a cognitive mediator

in the pain experience and a predictor of the pain experience as indicated by

heightened pain sensations and lower thresholds for pain for catastrophizers. Relatively

few studies have investigated the direct relationship between positive cognitions and

pain. The present study measured the effects of response expectancies

(catastrophizing self-statements and positive coping self-statements) on cold pressor-

induced pain.

Participants were 58 adult chronic pain patients with current facial pain. It was

hypothesized that catastrophizing would lead to a decrease in pain endurance whereas

positive coping would lead to an increase in pain endurance. It was also hypothesized

that catastrophizing would lead to an increase in peak pain intensity whereas positive

coping would lead to a decrease in peak pain intensity.

Participants signed a consent form explaining possible risks associated with the

experiment. The University of Florida Institutional Review Board approved the

procedures and protocols of the study. A cold pressor apparatus was used to induce

pain in participants. A pressure sensitive bladder/transducer was used to measure pain

10

intensity. Pain endurance was determined by calculating the difference between

tolerance and threshold. At pretest, participants submerged their non-dominant hand in

the cold pressor. Pain endurance and peak pain intensity measurements were

recorded. Participants underwent random assignment to a catastrophizing group or a

positive coping group. Participants chose one coping statement from a given list to use

as a coping strategy during the test phase.

ANCOVA results indicated a significant effect of coping on pain endurance after

controlling for pretest pain endurance, F(1, 36) = 5.525, p < .05. Manipulation of coping

explained 13.3% of the variance in test phase pain endurance. On average, participants

employing catastrophizing statements as a coping strategy experienced significantly

lower pain endurance (M = 35.53, SD = 39.71) compared to participants employing

positive coping statements (M = 73.70, SD = 86.14). However, the type of coping

statement (group assignment) used had no significant influence on peak pain intensity

measurements.

Most previous work showing a coping-pain relationship cannot confirm causality of

the relationship. The results of this research show that manipulation of coping causes

changes in pain behavior. This provides a mechanism for considering how response

expectancies mediate pain endurance in clinical settings, ultimately leading to more

effective treatment options.

11

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

Coping

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) best defined coping as an active effort to manage or

control a perceived stressor. Nevertheless, there is no universally agreed upon

operational definition of what constitutes a coping strategy or a universally agreed upon

way to classify the several different coping strategies that have been identified. A

frequently used classification system within the context of chronic pain centers around

the dichotomy of active versus passive coping. Passive coping includes those strategies

in which one surrenders control or withdraws from the pain (Van Damme, Crombez, &

Eccleston, 2008). Conversely, active coping strategies are those involving an attempt to

control or manage the pain or to persevere regardless of the experienced pain (Van

Damme, et al., 2008). The present study will focus specifically on catastrophizing and

positive coping self-statements which are two types of coping strategies representing

passive coping and active coping, respectively.

Catastrophizing

Catastrophizing is the tendency to exaggerate the negative outcomes of a

situation (Turner, Jensen, & Romano, 2000). More specifically, pain catastrophizing is

characterized by pessimistic cognitions leading to exaggerations and negative

expectations of the pain experience such as heightened pain perceptions. It involves

elements of helplessness and pessimism as captured by the catastrophizing subscale

of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (Rosenstiel & Keefe, 1983). Within the

aforementioned classification system catastrophizing is a type of passive coping (Van

Damme, et al., 2008). Catastrophizing has been well-established in the literature as a

12

cognitive mediator in the pain experience and a predictor of the pain experience as

indicated by heightened pain sensations and lower thresholds for pain for

catastrophizers (George & Hirsch, 2008; Keefe, et al., 2000; Sullivan, Rodgers, &

Kirsch, 2001; Sullivan, Thorn, Rodgers, & Ward, 2004). Research also suggests a

positive correlation between catastrophizing and depression exists in chronic pain

patients (Lee, Wu, Lee, Cheing, & Chan, 2008; Lopez-Lopez, Montorio, Izal, & Velasco,

2008; Sullivan & D'Eon, 1990; Turner, et al., 2000). Despite the wealth of literature

regarding catastrophizing and pain, most research has been correlational supporting the

notion of an antecedent relationship but not a causal one (Roth, Lowery, & Hamill, 2004;

Severeijns, Vlaeyen, van den Hout, & Weber, 2001; Sullivan, et al., 2001; Sullivan, et

al., 2004).

Positive Coping Self-Statements

Positive coping self-statements are those which encourage the individual to persist

despite pain or to reassess the situation in a more positive light. Relatively few studies

have investigated the direct relationship between positive cognitions and pain. Some

research has found that higher use of coping self-statements was predictive of higher

perceptions of control over pain (Haythornthwaite, Menefee, Heinberg, & Clark, 1998).

Moreover, it has been suggested that positive coping self-statements interact with level

of pain intensity (Jensen & Karoly, 1991; Jensen, Turner, & Romano, 1992). There is

some indication that positive coping self-statements are correlated with fewer

depressive symptoms (Walker, Smith, Garber, & Claar, 2005).

Response Expectancies

Response expectancies have been defined in the literature as non-volitional

responses to events (Kirsch, 1985). These are differentiated from Rotter’s social

13

learning theory concept of outcome expectancies by virtue of being automatic rather

than meditated responses as is the case with outcome expectancies (Kirsch, 1985;

Rotter, 1954). In addition, response expectancies have been typically differentiated by

their virtue of being self-confirming. It has been suggested that response expectancies

may be a mechanism by which psychotherapy produces change for the patient (Milling,

Reardon, & Carosella, 2006). In particular, Milling et al. posit that response

expectancies may produce analgesia in pain treatments by creating a cognitive set in

which the individual being treated comes to expect reductions in pain (2006). Therefore,

we propose that response expectancies and voluntary cognitive efforts need not be

mutually exclusive concepts. It seems as though the cognitive set believed to be

responsible for analgesic relief in pain treatments exemplifies this proposition. If a

cognitive set is established, it is no longer an automatic, non-volitional response but

rather a deliberate, effortful process. Furthermore, if theory regarding response

expectancies is expanded to include both non-volitional and volitional expectations, then

we hold that these can be manipulated by altering existing or creating new cognitive

sets in which a person expects either diminished pain or increased pain. Therefore, a

possible mechanism by which expectancies can be manipulated is via alteration of

coping self-statements. Positive self-statements can be induced in participants to

produce a change of expectations of a more favorable outcome. Likewise,

catastrophizing statements may be a mechanism by which expectancies can be

negatively manipulated, resulting in pessimistic expectations for a worse outcome.

Previous Coping Research

Previous research found that preexisting catastrophizing predicted higher pain

intensity in an experimental task on children and adolescents, whereas preexisting

14

positive coping self-statements predicted lower pain intensity (Lu, Tsao, Myers, Kim, &

Zeltzer, 2007). Research by Severeijns et al. found that, although catastrophizing was

successfully manipulated in participants in the experimental group condition, it did not

moderate the pain experience as neither pain expectancy levels, nor experienced peak

pain intensity levels, nor pain tolerance differed significantly from those of participants in

the control group condition (2005). It is important to further investigate the relationship

between catastrophizing and pain as well as positive coping and pain using an

experimental research design in order to infer a causal relationship between cognitions

and pain experience.

Current Study

The present study aimed to build on the current literature on catastrophizing and

pain and positive coping and pain from an experimental perspective by directly

manipulating the constructs in a sample of adult chronic pain patients. Most previous

studies have not directly manipulated catastrophizing or positive coping and findings

from studies that have done so are not consistent with the hypothesized theory (Lu, et

al., 2007; Severeijns, et al., 2005). The primary aims were to evaluate the effects of

catastrophizing and positive coping on Pain Sensitivity Range (PSR) and peak pain

intensity measurements during experimentally induced pain using the cold pressor task.

It was hypothesized that catastrophizing would lead to a decrease in pain endurance as

measured by PSR whereas positive coping would lead to an increase in pain endurance

as measured by PSR. It was also hypothesized that catastrophizing would lead to an

increase in peak pain intensity measurements whereas positive coping would lead to a

decrease in peak pain intensity measurements.

15

CHAPTER 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Procedure

Participants signed a consent form explaining possible risks associated with the

experiment and were all assured that they could withdraw from the study at any time

without negative consequences if they chose to. The University of Florida Institutional

Review Board approved the procedures and protocols of the study.

In the pretest, all participants submerged their non-dominant hand, palm facing

down, in the cold pressor apparatus. Participants were instructed to say “pain” when

they first experienced pain (to measure pain threshold) and to keep their hand

submerged in the cold water as long as possible (to measure pain tolerance). Pain

sensitivity ranges were subsequently determined for each participant by calculating the

difference between pain tolerance time and pain threshold time. Pain intensity

measurements were recorded as indicated by the pressure sensitive

bladder/transducer. Participants were instructed to press the pressure sensitive

bladder/transducer to indicate the level of pain intensity throughout the duration of the

cold pressor task. Only peak pain intensity measurements were used for data analyses.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: catastrophizing self-

statements or positive coping self-statements. Participants in each group were asked to

rehearse statements from the designated lists and instructed to choose one statement,

repeated aloud, to use as a coping strategy for the duration of the cold pressor task

during the test phase.

In the test phase participants repeated the cold pressor task following the same

protocol as the pretest with the addition of the chosen coping strategy repeated aloud.

16

Pain threshold and pain tolerance were reassessed. New pain intensity measurements

were recorded as indicated by the pressure sensitive bladder/transducer.

Upon completion of the test phase, participants were debriefed concerning the

nature of the study. All participants received information regarding appropriate coping

strategies in the management of chronic pain. Figure 2-1 shows a flowchart diagram of

the experimental procedures.

Participants

Adult chronic pain patients (N = 58) with current facial pain stemming from

temporomandibular disorders (TMD) were recruited from the Parker Mahan Facial Pain

Center at the University of Florida. Eligibility criteria excluded all those with pain

duration shorter than six months, those with pain related to malignant process, those

with upper extremity pain, and those with history of severe cardiovascular disease. The

mean age of the sample was 39.30 (range 18-65, SD = 11.68) years. Forty-nine

participants were female and nine were male. Primary diagnoses included myofascial

pain syndrome, bruxism, noxious occlusion, degenerative arthritis, fibromyalgia, and

disk displacement. Participants had a mean education level of 13.88 years (SD = 1.90).

The mean duration of pain was 97.69 (SD = 95.74) months. The majority of participants

were married (38), 15 were single, 4 were divorced, and 1 was widowed. The sample

was predominantly Caucasian (56); the remaining participants were African American

(2). Thirty-seven participants were currently employed; the remaining twenty-one were

currently unemployed. Table 2-1 provides demographic information for the total sample

of facial pain patients.

17

Apparatuses

A cold pressor apparatus was used to induce pain in participants. It consisted of a

2.5 cubic foot thermal cooler divided by a fitted screen. One side of the apparatus

contained cold water whereas the other side contained ice. Water circulated from one

side to the other via a dc bilge pump allowing for water to remain at a constant

temperature range of 1-3 degrees Celsius. The 1-3 degree variation in the water

temperature in the cold pressor is within standard parameters for a cold pressor task.

Figure 2-2 displays a picture of a cold pressor apparatus used to induce pain in

participants.

A pressure sensitive bladder/transducer was used to measure individual ratings of

pain intensity in response to the cold pressor apparatus. The pressure sensitive bladder

consisted of a blood pressure monitor inflation device linked to a computer via a

pressure transducer (an HC11 microprocessor) allowing for analog to digital conversion.

The device required 20 lbs. of force to reach a maximum voltage of 5 volts. No subjects

were able to maximize this pressure/voltage, thus eliminating the possible confound of

ceiling effects. The resolution of the processor allowed for measurement sensitivity to

increments of .01 volts.

Measures

Demographics

A self-report questionnaire was used to gather demographic information from all

participants. Questions inquired about participants’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital

status, years of education attained, employment status, pain duration, and primary pain

diagnosis.

18

Coping Statements

A list of catastrophizing statements was derived from the Coping Strategies

Questionnaire CSQ-CAT subscale (Rosenstiel & Keefe, 1983) and a list of positive

coping statements was created by using statements opposite of the catastrophizing

statements generated. Table 2-2 reports the list of catastrophizing self-statements given

to participants in the negative coping group. Table 2-3 reports the list of positive coping

self-statements given to participants in the positive coping group.

Pain Threshold

Pain threshold was determined by the amount of time elapsed from initial

immersion of hand into the cold pressor apparatus to the moment participants verbally

indicated they felt pain.

Pain Tolerance

Pain tolerance was determined by the amount of time elapsed from initial

immersion of hand into the cold pressor apparatus to the moment participants removed

their hand from the cold pressor. A limit of 300 seconds was set for tolerance at which

point participants were asked to remove their hand due to risk of injury. A total of ten

participants reached the tolerance limit at one or both of the testing phases.

Pain Endurance

Pain sensitivity ranges were determined for each participant by calculating the

difference between tolerance and threshold. PSR was used as a measure of pain

endurance and has been found to be a more stable measure of pain than pain tolerance

(Wolff, 1986). Thus, this was selected as the dependent variable to preclude bias

derived from pre-pain perception often inherent in threshold and tolerance ratings.

19

Pain Intensity

Peak pain intensity was determined by the selecting the highest voltage pain

intensity measurement as indicated by the pressure sensitive bladder/transducer.

Table 2-1. Demographic variables of total sample (N = 58) Demographic variables n % years or months Gender

Males 9 15.52% Females 49 84.48%

Mean Age (in years) 39.30 (SD = 11.68) Ethnicity

Caucasian 56 96.55% African American 2 3.45%

Marital Status Married 38 65.52% Divorced 4 6.90% Widowed 1 1.72% Single 15 25.86%

Mean Years of Education 13.88 (SD = 1.90) Employment

Employed 37 63.79% Unemployed 21 36.21%

Mean Pain Duration (in months) 97.69 (SD = 95.74)

20

Table 2-2. List of Catastrophizing Self-Statements 7 Catastrophizing Statements This is terrible. This is never going to get better. This is overwhelming. I cannot control the pain. This is worse than I thought. I can’t stand it anymore. I feel like I can’t go on.

21

Table 2-3. List of Positive Coping Self-Statements 7 Positive Coping Statements One step at a time, I can handle it. I just have to remain focused on the positives. It will be over soon. I can control the pain. It won't last much longer. This isn't as bad as I thought. No matter how bad it gets, I can do it.

22

Informed Consent Signed

Pretest: Cold Pressor Task

Random Group Assignment

PSR calculated and recorded

Catastrophizing Self-Statements Group Positive Self-Statements Group

Test phase: Cold Pressor Task using selected Coping strategy

Test phase: Cold Pressor Task using selected Coping strategy

PSR Calculated and recorded Peak Pain Intensity recorded

PSR Calculated and recorded Peak Pain Intensity recorded

Debriefing

Debriefing

Rehearsal of Statements

Rehearsal of Statements

Figure 2-1. Experimental Procedure Flowchart

23

Figure 2-2. Cold Pressor Apparatus. Taken in 2010 in the Center for Pain Research laboratory

24

CHAPTER 3 RESULTS

The statistical analyses conducted to evaluate the hypotheses for this research

project were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). An

alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests. Variables were examined on a list-

wise basis for each hypothesis; thus, excluding from the analyses participants for whom

data from variables of interest were missing.

Descriptive Analyses

A comparison of the catastrophizing self-statements group and the positive coping

self-statements group was conducted to assess for any significant differences among

demographic variables between the two groups. Levene’s test results were non-

significant for the variables examined: age, race, number of years of education attained,

employment status, duration of pain, and pretest pain endurance; thus, we failed to

reject the assumption of homogeneity of variances. Results of a one-way independent

ANOVA revealed that on average, participants in the catastrophizing self-statements

group did not differ significantly from participants in the positive self-statements group

along the dimensions of age, race, number of years of education attained, employment

status, duration of pain, or pretest pain endurance. Table 3-1 reports Levene’s statistics,

F statistics, means, standard deviations, and probability values for the variables

analyzed.

First Hypothesis- Pain Endurance

In the analyses of our first hypothesis, of the initial 58 participants, only the data

from 39 participants were used. Data from the remaining participants were excluded as

PSRs could not be calculated because participants either reached the maximum

25

tolerance time of 300 seconds or did not indicate “pain” and, thus, threshold time could

not be determined. Among those participants excluded from the analyses, 9 were

assigned to the catastrophizing group and 10 to the positive self-statements group.

Between-group analyses revealed participants did not differ among demographic

variables (see Table 3-1).

On average, participants employing catastrophizing statements as a coping

strategy experienced a 20.05 second decreased PSR (pretest M = 55.58, SD = 72.45,

test phase M = 35.53, SD = 39.71) and participants employing positive coping self-

statements showed a 12.15 second increase in PSR (pretest M = 61.55, SD = 87.32,

test phase M = 73.70, SD = 86.14), as shown in Figure 3-1. To test the effect of coping

statement manipulation an ANCOVA with test phase PSR as the dependent variable

and pretest PSR as the covariate was performed. Results indicated that after controlling

for pre-manipulation PSR, post-manipulation PSR differed between the two coping

statement groups. Results indicated a significant effect of coping on PSR after

controlling for pretest PSR, F(1, 36) = 5.525, p < .05. Manipulation of coping explained

13.3% of the variance in test phase PSR (see Table 3-2).

It should be noted that our findings did not reveal any within-group effects. Paired

samples t-tests indicated that although the positive coping self-statements and the

catastrophizing self-statements groups differed significantly from one another at test

phase (between-groups effect), each group’s endurance at test phase was not

significantly different from the mean at pretest, t(19) = -1.05, p = .305, d = .33 and t(18)

= 1.54, p = .140, d = .59, respectively. Therefore, the post-intervention difference

represents the combination of smaller within-group endurance effects in opposite

26

directions (as hypothesized). The absence of statistically significant within-group

differences is likely a function of an underpowered sample size. Nevertheless, d = .33

and d = .59 represent small to medium and medium effect sizes, and suggest these

findings might represent meaningful relationships. Of note, there were no significant

between-group PSR differences at pretest, t(45) = -.065, p = .948.

Second Hypothesis- Peak Pain Intensity

In the analysis of our second hypothesis, of the initial 58 participants, only the data

from 50 participants were used. Data from the remaining participants were excluded as

no pain intensity measurements were recorded for them.

On average, participants employing catastrophizing statements as a coping

strategy did not experience a significant change in test phase peak pain intensity

(pretest M = 1.81, SD = .20, test phase M = 1.86, SD = .29) compared to participants

employing positive coping self-statements (pretest M = 1.83, SD = .18, M = 1.83, SD =

.19). To test the effect of coping statement manipulation an ANCOVA with test phase

peak pain intensity measurement as the dependent variable and pretest peak pain

intensity measurement as the covariate was performed. Results indicated that after

controlling for pre-manipulation peak pain intensity measurement, post-manipulation

peak pain intensity measurement did not differ significantly between the two coping

statement groups. Results indicated a non-significant effect of coping on peak pain

intensity measurement after controlling for pretest peak pain intensity measurement,

F(1, 47) = .705, p > .05 (see Table 3-2).

27

Table 3-1. ANOVA results of comparison between two coping groups

Demographic Variables n Levene's statistic p

F statistic p Mean SD

Age 2.36 0.13 0.72 0.79 Positive Coping 29 38.93 10.69

Catastrophizing 29 39.76 12.77

Race 1.72 0.20 0.40 0.53 Positive Coping 29 1.03 0.19

Catastrophizing 29 1.10 0.56 Years of Education attained 0.00 0.96 0.01 0.95

Positive Coping 29 13.86 1.77

Catastrophizing 29 13.90 2.04

Employment Status 0.29 0.60 0.07 0.79 Positive Coping 29 0.62 0.49

Catastrophizing 29 0.66 0.48 Pain Duration (in months) 0.01 0.91 1.43 0.24

Positive Coping 29 82.69 105.38

Catastrophizing 29 112.69 84.20

Pretest PSR (in seconds) 0.23 0.63 0.00 0.95 Positive Coping 23 56.91 82.14

Catastrophizing 24 58.46 79.63

28

Figure 3-1. Effects of coping manipulation on PSR.

Note: Mean pain sensitivity ranges in seconds. Error bars represent standard error.

29

Table 3-2. Mean PSR and Peak Pain Intensity Measurements of Catastrophizing and Positive Self-Statement (PSS) Groups

________________________________________________________________________ Mean Standard deviation

___________________ ___________________ Group Pretest Test phase Pretest Test phase ________________________________________________________________________ PSR (n = 39) Catastrophizing 55.58 35.53* 72.45 39.71 PSS 61.55 73.70* 87.32 86.14

________________________________________________________________________

Peak Pain Intensity Measurement (n = 50) Catastrophizing 1.81 1.86 .20 .29 PSS 1.83 1.83 .18 .19 ________________________________________________________________________ Note. Maximum PSR = 300 seconds. Maximum Peak Pain Intensity = 5 volts. Means marked with an asterisk differ at p < .05. ANCOVA results indicated that after controlling for pre-manipulation PSR, post-manipulation PSR differed between the two coping statement groups. Results indicated a significant effect of coping on PSR after controlling for pretest PSR, F(1, 36) = 5.525, p < .05. Manipulation of coping explained 13.3% of the variance in test phase PSR.

30

CHAPTER 4 DISCUSSION

By manipulating the use of coping strategies we were able to evaluate the effects

of catastrophizing and positive coping self-statements on pain endurance (PSR) and

peak pain intensity during experimentally induced pain. As indicated in the results

section, the catastrophizing and positive coping self-statements groups differed post-

intervention. Examination of Figure 3-1 and of the within-group effect sizes suggests

that the post-interventions differences resulted from smaller non-significant within-

groups effects in opposite directions (as hypothesized). The direction of these findings

supports extant literature stating catastrophizing is a mediator in the pain experience

(Edwards, Haythornthwaite, Sullivan, & Fillingim, 2004; Keefe, et al., 2000; Sullivan, et

al., 2001; Sullivan, et al., 2004; Turner, Holtzman, & Mancl, 2007). Furthermore, using

random assignment and the experimental manipulation of coping statements, results

support a causal relationship between coping self-statements and pain perception.

Specific evidence suggesting catastrophizing uniquely contributes to decreases in pain

endurance is inconclusive. Although several research findings have not found

catastrophizing to uniquely affect pain tolerance time there are some research findings

supporting this notion (France, et al., 2004). It is possible that when several mediators

and predictors of pain are evaluated, shared variance (e.g. negative affect, fear of pain)

eclipses the unique contribution of catastrophizing (Hirsh, George, Bialosky, &

Robinson, 2008; Hirsh, George, Riley, & Robinson, 2007). More work on the unique

contributions of negative and positive coping, and negative mood measures is

warranted.

31

Additionally, it is important to highlight that although our results are not applicable

to a direct numerical translation to changes in clinical pain endurance, the magnitude of

raw change produced by our manipulation is substantial. Specifically, participants in the

catastrophizing self-statements group experienced a 56.43% decrease in endurance

(20.05 seconds) and those in the positive self-statements group experienced a 16.49%

increased endurance (12.15 seconds). We propose that such a change would be of

great clinical significance if similar changes were to occur in a clinical setting.

This study adds to the body of literature by furthering the hypothesis of an

antecedent relationship between catastrophizing and decreased pain endurance and

positive coping. Additionally, it adds to the current body of literature by demonstrating

the effects (changes in pain endurance) of experimental manipulation of coping

strategies. These findings lend support for this being a potential causal association

between coping strategy and pain endurance. It is possible that the use of PSR as a

measure of pain endurance is a viable explanation for why we successfully found

effects of coping on the pain experience in light of the divergent findings in the extant

literature regarding pain tolerance time (France, et al., 2004; Lu, et al., 2007;

Severeijns, et al., 2005). Whereas other measures of tolerance do not measure the time

period of experienced pain and instead measure the time point at which pain becomes

unbearable, our measure of endurance includes only the time period during which one

is coping with experienced pain by excluding the time period prior to threshold; a subtle

but potentially important difference. This explanation would suggest that effects of pain

endurance ought to be considered in future research alongside the more commonly

used measures of pain threshold and pain tolerance.

32

A second aim was to examine the effects of catastrophizing and positive coping on

peak pain intensity measurements. Results did not support our hypothesis. The

manipulation of coping strategies did not affect peak pain intensity measurements

signifying participants did not experience heightened pain upon employing

catastrophizing coping strategies nor did they experience a decrease in pain upon

employing positive self-statements as coping strategies. Interestingly, although our

findings did not support such a relationship, the positive relationship between

catastrophizing and heightened pain sensations is widely supported in the extant

literature (George & Hirsch, 2008; Keefe, et al., 2000; Picavet, Vlaeyen, & Schouten,

2002; Sullivan, et al., 2001; Sullivan, et al., 2004). Taken together these findings

suggest that the manipulation of coping strategies led participants in our sample to

endure pain differentially despite the fact that they were experiencing the same peak

pain intensity as they were prior to the manipulation of coping. Interestingly, this lends

support for the theory that expectations, rather than demand characteristics, may be the

underlying mechanism responsible for the changes in pain endurance. If, indeed,

demand characteristics induced by the statements were responsible for the changes

observed at test phase then both, pain endurance and pain intensity measurements,

should have changed. Instead our results show that the only change was participants’

willingness to endure pain regardless of experiencing the same peak intensity of pain.

Nevertheless, it is a possibility that demand characteristics motivated participants in the

positive coping self-statements group to endure pain for a longer period of time and

participants in the catastrophizing self-statements group for a shorter duration of time.

Participants, therefore, may have simply been behaving in a manner consistent with the

33

way they believed the experimenter expected them to behave. It remains to be

determined if the failure to affect peak pain intensity is a function of the manner in which

peak pain intensity was obtained in this study, or if cognitive strategies more strongly

operate on more tonic pain, or the endurance of pain. The pressure sensitive

bladder/transducer we employed allowed for precise .5 second resolution of pain

intensity, and unlike other pain intensity measurements, it did not ask participants to rely

on retrospective assessment or cumulative averages of their pain in order to rate it.

Therefore, it is possible that the absence of a cognitive component in measurement

unique to pain may partially account for the lack of coping manipulation effects on peak

pain intensity.

Response expectancies have been found to have a significant concordant

influence on the pain experience (Baker & Kirsch, 1991; Sullivan, et al., 2001). There is

support for the theory that response expectancies partially mediate the relation between

catastrophizing and the pain experience and it is likely that response expectancies may

also mediate the relation between optimism and the pain experience (Sullivan, et al.,

2001). Although there are mixed findings in the literature, optimism has been found to

partially mediate pain intensity in cancer patients and in laboratory induced pain

(Geers, Wellman, Helfer, Fowler, & France, 2008). Recent literature reveals that the

placebo effect is an example of how expectancies may influence and determine the pain

experience (Pollo, et al., 2001; Vase, Robinson, Verne, & Price, 2003). Similarly, we

assumed that presenting participants with self-statements of poor pain coping

(catastrophizing) or increased pain coping (positive expectations) would generate

underlying pain expectations responsible for the changes in PSR. Consistent with the

34

observed effect of catastrophizing and pain in this study, negative expectations have

been found to be unique contributors to a heightened pain experience (Montgomery &

Bovbjerg, 2004; Sullivan, et al., 2001). Unfortunately, research exploring positive

expectations and their relationship to pain experience is scarce in comparison and

findings are often inconclusive. Research has tended to focus predominately on

negative contributors to the pain experience almost to the exclusion of positive

protective factors in the pain experience. Therefore, although there is some evidence

regarding the association between negative and positive expectations, pessimism and

optimism, and decreased pain, additional research in this area is warranted.

Clinical Implications

As aforementioned our results are not applicable to a direct translation to changes

in clinical pain endurance; nevertheless, the changes produced by our manipulation

reflect changes commonly obtained through efficacious clinical interventions. While

cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions may vary substantially, CBT

interventions generally include common components such as psychoeducation,

relaxation techniques, training in effective coping strategies, and cognitive restructuring

specifically targeting dysfunctional/unrealistic thoughts. In the context of chronic pain

interventions, CBT has been found to be efficacious (Morley, Eccleston, & Williams,

1999) although the exact components that lead to successful outcomes have yet to be

discerned. It has been suggested that, perhaps, the improvement of self-efficacy may

be one of the principal common factors driving successful outcomes (Turk, Swanson, &

Tunks, 2008). Therefore, a possible mechanism by which self-efficacy can be increased

is through the attainment of favorable expectations (i.e. positive self-statements) and

the reduction of pessimistic expectations (i.e. catastrophizing self-statements).

35

Research in a sample of chronic headache sufferers revealed that CBT interventions

aimed at reducing catastrophizing and adopting cognitive coping strategies (positive

self-statements regarding ability to manage headaches) alongside behavioral coping

strategies revealed that this intervention led to significant improvements headache

experience marked by reductions in the headache frequency and peak intensity, the

reduction of catastrophizing, and significant increases in headache management self-

efficacy as measured by self-report assessments (Thorn, et al., 2007). Changes were

maintained at post-treatment and 12 month follow-up (Thorn, et al., 2007). Our findings

coupled with clinical intervention findings suggest that pain-relief expectations are highly

amenable to change and are responsive to pain-specific cognitive-behavioral treatments

in select patient populations.

Methodological Limitations and Future Research Directions

The generalizability of the findings in this study is limited to our sample. A design

limitation includes the absence of a neutral control group as the pre-post design is

subject to pretest sensitization. The absence of a specific manipulation check prevents

us from conclusively knowing if our manipulation of coping was responsible for the

changes in pain endurance. However, it should be taken into account that participants

were instructed to verbalize and repeat aloud the coping strategy they selected

throughout the test phase therefore ensuring participants were at least partially

cognitively engaging in the particular strategy (via awareness and verbalization). As

previous findings in CBT research suggest, it is a plausible explanation that participants’

expectations for pain relief or ability to endure pain changed as a function of the

manipulation of coping (Jensen, Turner, & Romano, 2001; Smeets, Vlaeyen, Kester, &

Knottnerus, 2006; Turner, Dworkin, Mancl, Huggins, & Truelove, 2001; Turner, Mancl, &

36

Aaron, 2006). Nevertheless, the absence of such a manipulation check tempers a

causal inference regarding the effect of changing expectations as the mechanism for

change (increased/decreased endurance) in the pain experience.

Another design limitation is that experimenters were not blinded to the condition or

the hypotheses. However, because the data were collected using objective time

measurements and electronic/mechanical devices it is unlikely this would introduce

experimenter bias. Furthermore, it is possible that the cold pressor task was not an

optimal analog of chronic clinical pain and that other pain induction strategies would

have been more appropriate. Of note, there is no evidence of systematic variance due

to variation in the water temperature in the cold pressor and, thus, no concern of

confound effects. As noted in the materials and methods section, the temperature

variation is within standard parameters of the cold pressor task. It should also be noted

that no data are available regarding the reliability and validity of the pressure sensitive

bladder/transducer used to measure pain intensity. This precludes comparison of our

obtained measurements with those obtained from existing well-established methodology

for measuring pain intensity such as Visual Analog Scale (VAS).

Our reliance on PSR as a measure of pain endurance strongly reduced our

sample size from 58 to 39, excluding 19 participants for whom PSR could not be

calculated. The reduction in sample size may have rendered our study underpowered

and may influence the validity of our results. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the

exclusion of participants was not selective as the two groups did not differ significantly

in between-group analyses of demographic variables. In evaluating our results, it is

important to consider the brevity and limited scope of our coping manipulation strategy.

37

Thus, it is suggested that further experimental research be conducted on the effects of

catastrophizing and positive coping in the pain experience using more diverse chronic

pain samples as well as different pain manipulation strategies. Additional measures of

expectation, both situational and dispositional, are important to further understand the

potential of expectancies as a mechanism in pain coping strategies, both positive and

negative. Lastly, it would be of interest to assess pre-existing coping predispositions

prior to pretest and test phase in order to allow for potential associations between

habitual (baseline) coping response predispositions and the effects of experimental

manipulation of coping. Assessing pre-existing coping predispositions would also allow

experimenters to discern if there are differential results when participants are assigned

to a coping condition contradicting their habitual coping style as compared to being

assigned to a coping condition that is consistent with their preferred coping strategy

repertoire.

38

CHAPTER 5 SUMMARY

This study investigated the effects of chronic pain patients’ response expectancies

on pain endurance and peak pain intensity measurements during an experimental pain

task. Response expectancies were manipulated by manipulating participants’ coping

behaviors to induce catastrophizing or positive coping following pain experimentally

induced using a cold-pressor. Fifty-eight participants were asked to complete the cold

pressor task (immersion of non-dominant hand in a bath of cold water) as part of the

pretest. Ensuing pain endurance and perceived peak pain intensity measurements were

established. Participants selected a coping statement (either a catastrophizing self-

statement or a positive coping self-statement depending on random group assignment)

from a list of seven self-statements. Using their selected coping statement, participants

repeated the cold pressor task during the test phase. Pain endurance and peak pain

intensity measurements were subsequently reestablished.

Whereas during the pretest participants’ pain endurance and peak pain intensity

ratings did not differ, participants assigned to the positive coping self-statement

condition endured pain for a significantly longer duration of time during the test phase

as compared to participants assigned to the catastrophizing self-statement condition.

Interestingly, peak pain intensity ratings were not affected by the manipulation of

participants’ coping response as there were no differences between the groups’

measurements from pretest to test phase. Collectively, these results indicate that the

manipulation of participants coping responses led to them to endure pain differentially

during the test phase despite experiencing the same intensity of pain as experienced

during the pretest. These results suggest that the manipulation of response

39

expectancies via the manipulation of coping strategies is responsible for changes in the

pain experience as indicated by the changes in pain endurance observed in this study.

40

LIST OF REFERENCES

Baker, S. L., & Kirsch, I. (1991). Cognitive mediators of pain perception and tolerance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 504-510.

Edwards, R. R., Haythornthwaite, J. A., Sullivan, M. J., & Fillingim, R. B. (2004).

Catastrophizing as a mediator of sex differences in pain: differential effects for daily pain versus laboratory-induced pain. Pain, 111(3), 335-341.

France, C. R., Keefe, F. J., Emery, C. F., Affleck, G., France, J. L., Waters, S., et al.

(2004). Laboratory pain perception and clinical pain in post-menopausal women and age-matched men with osteoarthritis: relationship to pain coping and hormonal status. Pain, 112(3), 274-281.

Geers, A. L., Wellman, J. A., Helfer, S. G., Fowler, S. L., & France, C. R. (2008).

Dispositional optimism and thoughts of well-being determine sensitivity to an experimental pain task. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 36(3), 304-313.

George, S. Z., & Hirsch, A. T. (2008). Psychologic influence on experimental pain

sensitivity and clinical pain intensity for patients with shoulder pain. Journal of Pain.

Haythornthwaite, J. A., Menefee, L. A., Heinberg, L. J., & Clark, M. R. (1998). Pain

coping strategies predict perceived control over pain. Pain, 77(1), 33-39. Hirsh, A. T., George, S. Z., Bialosky, J. E., & Robinson, M. E. (2008). Fear of pain, pain

catastrophizing, and acute pain perception: relative prediction and timing of assessment. Journal of Pain, 9(9), 806-812.

Hirsh, A. T., George, S. Z., Riley, J. L., 3rd, & Robinson, M. E. (2007). An evaluation of

the measurement of pain catastrophizing by the coping strategies questionnaire. European Journal of Pain, 11(1), 75-81.

Jensen, M. P., & Karoly, P. (1991). Control beliefs, coping efforts, and adjustment to

chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 431-438. Jensen, M. P., Turner, J. A., & Romano, J. M. (1992). Chronic pain coping measures:

individual vs. composite scores. Pain, 51(3), 273-280. Jensen, M. P., Turner, J. A., & Romano, J. M. (2001). Changes in beliefs,

catastrophizing, and coping are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 655-662.

Keefe, F. J., Lefebvre, J. C., Egert, J. R., Affleck, G., Sullivan, M. J., & Caldwell, D. S.

(2000). The relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior, and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizing. Pain, 87(3), 325-334.

41

Kirsch, I. (1985). Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. American Psychologist, 40, 1189-1202.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York:

Springer. Lee, E. J., Wu, M. Y., Lee, G. K., Cheing, G., & Chan, F. (2008). Catastrophizing as a

cognitive vulnerability factor related to depression in workers' compensation patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 15(3), 182-192.

Lopez-Lopez, A., Montorio, I., Izal, M., & Velasco, L. (2008). The role of psychological

variables in explaining depression in older people with chronic pain. Aging and Mental Health, 12(6), 735-745.

Lu, Q., Tsao, J. C., Myers, C. D., Kim, S. C., & Zeltzer, L. K. (2007). Coping predictors

of children's laboratory-induced pain tolerance, intensity, and unpleasantness. Journal of Pain, 8(9), 708-717.

Milling, L. S., Reardon, J. M., & Carosella, G. M. (2006). Mediation and moderation of

psychological pain treatments: response expectancies and hypnotic suggestibility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 253-262.

Montgomery, G. H., & Bovbjerg, D. H. (2004). Presurgery distress and specific

response expectancies predict postsurgery outcomes in surgery patients confronting breast cancer. Health Psychology, 23(4), 381-387.

Morley, S., Eccleston, C., & Williams, A. (1999). Systematic review and meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain, 80(1-2), 1-13.

Picavet, H. S., Vlaeyen, J. W., & Schouten, J. S. (2002). Pain catastrophizing and

kinesiophobia: predictors of chronic low back pain. American Journal of Epidemiology, 156(11), 1028-1034.

Pollo, A., Amanzio, M., Arslanian, A., Casadio, C., Maggi, G., & Benedetti, F. (2001).

Response expectancies in placebo analgesia and their clinical relevance. Pain, 93(1), 77-84.

Rosenstiel, A. K., & Keefe, F. J. (1983). The use of coping strategies in chronic low

back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain, 17(1), 33-44.

Roth, R. S., Lowery, J. C., & Hamill, J. B. (2004). Assessing persistent pain and its

relation to affective distress, depressive symptoms, and pain catastrophizing in

42

patients with chronic wounds: a pilot study. American Journal of Physical and Medical Rehabilitation, 83(11), 827-834.

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning theory and clinical psychology. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall. Severeijns, R., van den Hout, M. A., & Vlaeyen, J. W. (2005). The causal status of pain

catastrophizing: an experimental test with healthy participants. European Journal of Pain, 9(3), 257-265.

Severeijns, R., Vlaeyen, J. W., van den Hout, M. A., & Weber, W. E. (2001). Pain

catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability, and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Clinical Journal of Pain, 17(2), 165-172.

Smeets, R. J., Vlaeyen, J. W., Kester, A. D., & Knottnerus, J. A. (2006). Reduction of

pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Journal of Pain, 7(4), 261-271.

Sullivan, M. J., & D'Eon, J. L. (1990). Relation between catastrophizing and depression

in chronic pain patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99(3), 260-263. Sullivan, M. J., Rodgers, W. M., & Kirsch, I. (2001). Catastrophizing, depression and

expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain, 91(1-2), 147-154. Sullivan, M. J., Thorn, B., Rodgers, W., & Ward, L. C. (2004). Path model of

psychological antecedents to pain experience: experimental and clinical findings. Clinical Journal of Pain, 20(3), 164-173.

Thorn, B. E., Pence, L. B., Ward, L. C., Kilgo, G., Clements, K. L., Cross, T. H., et al.

(2007). A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. Journal of Pain, 8(12), 938-949.

Turk, D. C., Swanson, K. S., & Tunks, E. R. (2008). Psychological approaches in the

treatment of chronic pain patients--when pills, scalpels, and needles are not enough. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(4), 213-223.

Turner, J. A., Dworkin, S. F., Mancl, L., Huggins, K. H., & Truelove, E. L. (2001). The

roles of beliefs, catastrophizing, and coping in the functioning of patients with temporomandibular disorders. Pain, 92(1-2), 41-51.

Turner, J. A., Holtzman, S., & Mancl, L. (2007). Mediators, moderators, and predictors

of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain, 127(3), 276-286.

43

Turner, J. A., Jensen, M. P., & Romano, J. M. (2000). Do beliefs, coping, and catastrophizing independently predict functioning in patients with chronic pain? Pain, 85(1-2), 115-125.

Turner, J. A., Mancl, L., & Aaron, L. A. (2006). Short- and long-term efficacy of brief

cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Pain, 121(3), 181-194.

Van Damme, S., Crombez, G., & Eccleston, C. (2008). Coping with pain: a motivational

perspective. Pain, 139(1), 1-4. Vase, L., Robinson, M. E., Verne, G. N., & Price, D. D. (2003). The contributions of

suggestion, desire, and expectation to placebo effects in irritable bowel syndrome patients. An empirical investigation. Pain, 105(1-2), 17-25.

Walker, L. S., Smith, C. A., Garber, J., & Claar, R. L. (2005). Testing a model of pain

appraisal and coping in children with chronic abdominal pain. Health Psychology, 24(4), 364-374.

Wolff, B. B. (1986). Behavioral measurement of human pain. In R. Sternbach (Ed.), The

Psychology of Pain (pp. 155). New York: Raven Press.

44

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

Daniela Roditi was born in Mexico City, Mexico. She is the daughter of Alberto

Roditi and Gabriela Dominguez. Daniela has a younger sister, Ana Laura Roditi, and an

older brother, Guillermo Roditi. Daniela graduated summa cum laude from Stetson

University in May 2008 with a Bachelor of Arts in psychology and a minor in health care

issues. She is currently residing in Gainesville, Florida and is pursuing a doctorate in

clinical and health psychology at the University of Florida.

Daniela’s research interests include coping behaviors, response expectancies,

and the use of analgesic placebos. Daniela is currently furthering her clinical training

experience in various settings. Her clinical experience includes conducting pediatric

neuropsychological assessments, structured comprehensive assessments specific to

populations of people with anxiety disorders, a range of medical psychology

assessments, and conducting psychological assessments with children. Daniela is also

currently involved in a randomized controlled clinical trial comparing the effects of

different cognitive behavioral therapies in a sample of fibromyalgia patients. Current

volunteer experiences include providing free brief therapy at a local community center

for residents of the community in need of psychological services. Daniela’s aspirations

within the field of clinical health psychology include an academic career that involves a

balance of teaching and clinical research opportunities.